Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Kant Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science

Caricato da

Anonymous MKQFghCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Kant Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science

Caricato da

Anonymous MKQFghCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (MFNS), Kant provides a “[special]

metaphysical doctrine of body” (4:473)1 in order to show the existence and extent of the proper

science of matter. In the Preface, however, Kant argues that both chemistry and “the empirical

doctrine of the soul” fail to be “a properly so-called natural science” (4:471). The empirical

doctrine of the soul falls especially short for two reasons: (1) mathematics is not applicable to its

subject matter and (2) unlike chemistry, the empirical doctrine of the soul can never become an

“experimental doctrine” because “the manifold of inner observation...cannot be held separate and

recombined at will” (4:471). In addition to these remarks in the Preface, I will identify another

argument – mostly in the Mechanics chapter – against the possibility of a proper science of the

soul: because the soul is not permanent, laws of the kind required by proper science cannot even

be formulated. Call the argument in (1) the impossibility argument (following (Sturm 2001))

and this later argument the impermanence argument.

I will analyze both of these arguments. In so doing, I will explicate just what Kant means

by proper science and, in particular, the role of the application of mathematics. Although much

of the literature on this aspect of MFNS has maintained that the impossibility argument plays a

far more pivotal role than the impermanence argument,2 I will show that a full analysis of the

impermanence argument pays dividends. In addition to shedding more light on the impossibility

argument, the impermanence argument elucidates the asymmetry between chemistry (which

Kant maintains may eventually become a proper science) and the empirical doctrine of the soul

(which Kant maintains can never so become), including the remarks mentioned in (2) above.

Understanding this argument can also explain the oft-overlooked and seemingly out-of-place

1 MFNS citations use Akademie pagination but are from Michael Friedman's translation. Quotations

from CPR

are from the Guyer-Wood translation.

2 (Sturm 2001) maintains that only the lack of (sufficient) mathematization prevents empirical

psychology from

becoming a proper science. (Nayak and Sotnak 1995) do not even discuss the impermanence argument.

2

assertion in the Remark to Proposition 3 (the Second Law of Mechanics) that “the possibility of a

proper natural science rests entirely and completely on the law of inertia (along with that of the

persistence of substance)” (4:544).

1. Terminology

I use the terms 'empirical doctrine of the soul' and 'empirical psychology' interchangably.

There is some evidence for such a substitution. In the Paralogisms of the CPR, Kant equates

rational psychology with “the rational doctrine of the soul” in contrast with “an empirical

doctrine of the soul” which is mixed with even “the least bit of anything empirical” (A342/B400).

(A342/B400). But in the MFNS, the empirical doctrine of the soul must be grounded by a

special metaphysics of nature which concerns itself with “the empirical concept of … a thinking

being” (4:470). Kant then refers to this doctrine as “psychology”. I will thus adopt the term

'empirical psychology'.3

2. The Impossibility Argument

Recall that Kant says that empirical psychology is not “a properly so-called natural

science” because “mathematics is not applicable to the phenomena of inner sense and their laws”

(4:471). In order to understand this claim, a few questions must be answered. What does Kant

mean by a proper science? Why does the inapplicability of mathematics render a doctrine not a

proper science? In what sense does mathematics fail to apply to empirical psychology? I turn to

the first two of these questions in the next section and then to the third.

2.1 Proper Natural Science and the Applicability of Mathematics

Kant begins the Preface of MFNS by drawing a distinction between nature in its formal

and material meaning. In the latter sense, with which MFNS is concerned, nature signifies “the

whole of all appearances” (4:467). Nature has two principle parts aligning with the division of

3 For the nuanced relationship between rational and empirical psychology, see (Hatfield 1992)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Kant PhilosophyDocumento14 pagineKant PhilosophyAle BaehrNessuna valutazione finora

- Friedman 2003 Transcendental PhilosophyDocumento15 pagineFriedman 2003 Transcendental PhilosophychiquilayoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant's Critique of Metaphysics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento18 pagineKant's Critique of Metaphysics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)BakulBadwalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Copernican Revolution in KantDocumento11 pagineThe Copernican Revolution in KantMassimVfre5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Computational Multiscale Modeling of Fluids and Solids Theory and Applications 2008 Springer 42 67Documento26 pagineComputational Multiscale Modeling of Fluids and Solids Theory and Applications 2008 Springer 42 67Margot Valverde PonceNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective Metaphysics Understanding QuaDocumento31 pagineReflective Metaphysics Understanding QuaX69hotdogNessuna valutazione finora

- A New More True Concept and Folmulae of Gravitation Based On The Heat of The Classical Fieldmatter. Newton's Gravitation As A Special Case.Documento36 pagineA New More True Concept and Folmulae of Gravitation Based On The Heat of The Classical Fieldmatter. Newton's Gravitation As A Special Case.Constantine KirichesNessuna valutazione finora

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Science: Katharina T. KrausDocumento12 pagineStudies in History and Philosophy of Science: Katharina T. KrausboxeritoNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Scientific Realism?Documento5 pagineWhat Is Scientific Realism?FritzSellisNessuna valutazione finora

- Horstmann, - The Problem of Purposiveness and The Objective Validity of JudgmeDocumento18 pagineHorstmann, - The Problem of Purposiveness and The Objective Validity of JudgmefreudlichNessuna valutazione finora

- Realism and Objectivism in Quantum Mechanics Vassilios KarakostasDocumento20 pagineRealism and Objectivism in Quantum Mechanics Vassilios KarakostasDigvijay KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Beauty As A Symbol of Natural Systematicity: Andrew ChignellDocumento10 pagineBeauty As A Symbol of Natural Systematicity: Andrew ChignellMatías OroñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomas Filk and Albrecht Von Muller - Quantum Physics and Consciousness: The Quest For A Common Conceptual FoundationDocumento21 pagineThomas Filk and Albrecht Von Muller - Quantum Physics and Consciousness: The Quest For A Common Conceptual FoundationSonyRed100% (1)

- Associate Prof. of University of Ioannina, Greece. Ckiritsi@Documento30 pagineAssociate Prof. of University of Ioannina, Greece. Ckiritsi@Constantine KirichesNessuna valutazione finora

- Cantor Theorem and OmniscienceDocumento17 pagineCantor Theorem and OmniscienceBayerischeMotorenWerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emergent Aspect Dualism View of Quantum PhysicDocumento17 pagineThe Emergent Aspect Dualism View of Quantum PhysicNor Jhon BruzonNessuna valutazione finora

- Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Da EverandProlegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Valutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (55)

- Kant Prolegomena - vs. Hume HandoutDocumento2 pagineKant Prolegomena - vs. Hume HandoutEmoEvoNessuna valutazione finora

- Two Kinds of Mechanical Inexplicability in Kant and AristotleDocumento33 pagineTwo Kinds of Mechanical Inexplicability in Kant and AristotlevereniceNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant's Fourth ParalogismDocumento27 pagineKant's Fourth ParalogismAnonymous pZ2FXUycNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant and The Human and Cultural SciencesDocumento31 pagineKant and The Human and Cultural SciencesJuan Carlos CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Generality of Kant's Transcendental Logic: Clinton TolleyDocumento33 pagineThe Generality of Kant's Transcendental Logic: Clinton TolleyPeter ZeviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aristotelian Teleology and The Principle of Least ActionDocumento12 pagineAristotelian Teleology and The Principle of Least ActionGeorge Mpantes mathematics teacherNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Michael Friedman Kants Constru PDFDocumento6 pagineReview of Michael Friedman Kants Constru PDFbobtelosNessuna valutazione finora

- From Deterministic World View To Uncertainty and Fuzzy Logic: A Critique of Artificial Intelligence and Classical LogicDocumento25 pagineFrom Deterministic World View To Uncertainty and Fuzzy Logic: A Critique of Artificial Intelligence and Classical LogicRajvardhan JaidevaNessuna valutazione finora

- T.Z. Kalanov. Crisis in Theoretical PhysicsDocumento20 pagineT.Z. Kalanov. Crisis in Theoretical PhysicscmlittlejohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Kants Theory of KnowledgeDocumento135 pagineKants Theory of KnowledgeFranzlyn SJ MarceloNessuna valutazione finora

- Immateriality: Kant's Theory of Mind: An Analysis of The Paralogisms of Pure ReasonDocumento54 pagineImmateriality: Kant's Theory of Mind: An Analysis of The Paralogisms of Pure ReasonEvyatar TurgemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant's Antinomies of Reason Their Origin and Their Resolution - Victoria S. WikeDocumento185 pagineKant's Antinomies of Reason Their Origin and Their Resolution - Victoria S. WikeTxavo HesiarenNessuna valutazione finora

- Beginning With The End - God, Science, and Wolfhart PannenbergDocumento33 pagineBeginning With The End - God, Science, and Wolfhart PannenbergPedro Fernandez50% (2)

- 3 The Inaugural Dissertation of 1770 and The Problem of Metaphysics - KopyaDocumento3 pagine3 The Inaugural Dissertation of 1770 and The Problem of Metaphysics - KopyaÜmit ÇakmakNessuna valutazione finora

- Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)Da EverandProlegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vol 15 No 1 Roy Why Metaphysics Matters PDFDocumento28 pagineVol 15 No 1 Roy Why Metaphysics Matters PDFmrudulaNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 Mechanical Explanation of Nature and Its Limits in Kant's Critique of JudgmentDocumento18 pagine05 Mechanical Explanation of Nature and Its Limits in Kant's Critique of JudgmentRicardo SoaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Critique of Practical Reason (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): and Other Works on the Theory of EthicsDa EverandCritique of Practical Reason (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): and Other Works on the Theory of EthicsValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- Oxford University Press Mind AssociationDocumento7 pagineOxford University Press Mind AssociationKatie SotoNessuna valutazione finora

- Allen W. Wood Preface and Introduction To Critique of Practical ReasonDocumento24 pagineAllen W. Wood Preface and Introduction To Critique of Practical ReasonnicolasberihonNessuna valutazione finora

- Epistemic and Ontic Quantum RealitiesDocumento22 pagineEpistemic and Ontic Quantum RealitiesJorge MoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Epistemic Structural Realism and Poincaré 'S Philosophy of ScienceDocumento22 pagineEpistemic Structural Realism and Poincaré 'S Philosophy of ScienceAnonymous kD1f7g2orNessuna valutazione finora

- The Chicken and Egg, RevisitedDocumento14 pagineThe Chicken and Egg, RevisitedC.J. SentellNessuna valutazione finora

- Nº 63 Peter Jacco Sas Pro-NaturalistepistemologyDocumento24 pagineNº 63 Peter Jacco Sas Pro-NaturalistepistemologyNicolas MarinNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematical NecessityDocumento27 pagineMathematical Necessityyoav.aviramNessuna valutazione finora

- Humeprinciples PDFDocumento16 pagineHumeprinciples PDFSeminarskii RadoviNessuna valutazione finora

- Two Aspects of Sunyata in Quantum PhysicDocumento31 pagineTwo Aspects of Sunyata in Quantum Physictihomiho100% (1)

- Kant's First Paralogism: Ian ProopsDocumento48 pagineKant's First Paralogism: Ian ProopsKristina NikolicNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphysics of MoralsDocumento9 pagineMetaphysics of MoralsManika AggarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Einstein On Locality and Separability PDFDocumento31 pagineEinstein On Locality and Separability PDFIgnacioPérezBurgaréNessuna valutazione finora

- Emergence: Towards A New Metaphysics and Philosophy of ScienceDa EverandEmergence: Towards A New Metaphysics and Philosophy of ScienceNessuna valutazione finora

- (2007) Kant, Philosophy in Last 100 Years and EDWs PerspectiveDocumento18 pagine(2007) Kant, Philosophy in Last 100 Years and EDWs PerspectiveGabriel VacariuNessuna valutazione finora

- Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological ScienceDa EverandAristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological ScienceValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Foundations of Statistical Mechanics: A Deductive TreatmentDa EverandFoundations of Statistical Mechanics: A Deductive TreatmentNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant-Metaphysics SCDocumento44 pagineKant-Metaphysics SCHoracio Ulises Rau FariasNessuna valutazione finora

- DualismcorrelateDocumento20 pagineDualismcorrelateRaúl SánchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Are Perceptual Fields Quantum Fields?: Brian FlanaganDocumento28 pagineAre Perceptual Fields Quantum Fields?: Brian FlanaganBrian FlanaganNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawsexp PDFDocumento20 pagineLawsexp PDFOscar MedellinNessuna valutazione finora

- John Earman - The "Past Hypothesis" Not Even FalseDocumento32 pagineJohn Earman - The "Past Hypothesis" Not Even Falsejackiechan8Nessuna valutazione finora

- Microscopes and The Theory-Ladenness of PDFDocumento37 pagineMicroscopes and The Theory-Ladenness of PDFgerman guerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- THE POINT OF KANT'S Axioms of Intuition PDFDocumento25 pagineTHE POINT OF KANT'S Axioms of Intuition PDFKatie SotoNessuna valutazione finora

- University of Cagayan Valley Senior High SchoolDocumento21 pagineUniversity of Cagayan Valley Senior High SchoolELMA MALAGIONANessuna valutazione finora

- What Is MOTIVATIONDocumento3 pagineWhat Is MOTIVATIONAngela ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Culture - Definition ElementsDocumento32 pagineCulture - Definition ElementsHarunur RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- NUR101 Learn Reflective Note PDFDocumento4 pagineNUR101 Learn Reflective Note PDFHarleen TanejaNessuna valutazione finora

- DEMONSTRATIONGOWRIDocumento6 pagineDEMONSTRATIONGOWRIValarmathi100% (2)

- Ethical Theories - Vurtue EthicsDocumento4 pagineEthical Theories - Vurtue EthicsNeha HittooNessuna valutazione finora

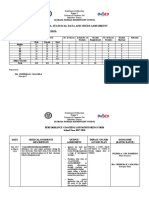

- School Statiscal Data and Needs AssessmentDocumento46 pagineSchool Statiscal Data and Needs AssessmentAileen Sarte JavierNessuna valutazione finora

- DLL March 5 Pictorial EssayDocumento4 pagineDLL March 5 Pictorial EssayJeppssy Marie Concepcion Maala100% (2)

- TEACHING LITERACY and NUMERACYDocumento29 pagineTEACHING LITERACY and NUMERACYEstrellita MalinaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Melvin UdallDocumento8 pagineMelvin Udallapi-315529794Nessuna valutazione finora

- 4.1. RPH - Introduction - 4Documento12 pagine4.1. RPH - Introduction - 4wani ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Voice Therapy Does Science Support The ArtDocumento1 paginaVoice Therapy Does Science Support The ArtEvelyn Bernardita Avello CuevasNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 4 ValuesDocumento12 pagineModule 4 ValuesAllen Mae ColoniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Formal and Informal GroupDocumento5 pagineFormal and Informal GroupRahul MadathilNessuna valutazione finora

- Will You, As The Human Resource Department Head, Accept The Boss' Will You, As The Human Resource Department Head, Accept The Boss'Documento2 pagineWill You, As The Human Resource Department Head, Accept The Boss' Will You, As The Human Resource Department Head, Accept The Boss'marichu apiladoNessuna valutazione finora

- Certificate in Primary Teaching (CPT) Module 1 of DPE Term-End Examination June, 2010 Es-202: Teaching of MathematicsDocumento4 pagineCertificate in Primary Teaching (CPT) Module 1 of DPE Term-End Examination June, 2010 Es-202: Teaching of MathematicsRohit GhuseNessuna valutazione finora

- Graduate Programs of Arts and SciencesDocumento4 pagineGraduate Programs of Arts and Sciencesthea billonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Ell Siop Lesson PlanDocumento2 pagineEll Siop Lesson Planapi-293758694Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 1-2: GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: Read The Specific Directions Carefully Before Answering The Exercises and ActivitiesDocumento11 pagineWeek 1-2: GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: Read The Specific Directions Carefully Before Answering The Exercises and ActivitiesRichelleNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 1 PerDev Assess Aspects of Your DevelopmentDocumento15 pagine2 1 PerDev Assess Aspects of Your DevelopmentPrimosebastian TarrobagoNessuna valutazione finora

- BARDINAS Women's Ways of Knowing G&SDocumento2 pagineBARDINAS Women's Ways of Knowing G&SRaymon Villapando BardinasNessuna valutazione finora

- Psyc110 Quiz & Final Exam Study GuideDocumento5 paginePsyc110 Quiz & Final Exam Study GuideEstela VelazcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Buddhist Meditation - KamalashilaDocumento258 pagineBuddhist Meditation - Kamalashilapaulofrancis100% (4)

- CSTP 6 Vernon 4 11 21Documento9 pagineCSTP 6 Vernon 4 11 21api-518640072Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dupont and Escrod 2016Documento10 pagineDupont and Escrod 2016Vrnda VinodNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan in Music Grade 6: Mu1Tx-Ive-2 Mu1Tx-Ivf-3Documento3 pagineLesson Plan in Music Grade 6: Mu1Tx-Ive-2 Mu1Tx-Ivf-3Alan Osoy TarrobagoNessuna valutazione finora

- JG13 - Interview Skills - Q&A Section - Sept. 2013 - IEEEAlexSBDocumento27 pagineJG13 - Interview Skills - Q&A Section - Sept. 2013 - IEEEAlexSBIEEEAlexSBNessuna valutazione finora

- Emerging Challenges of ManagementDocumento3 pagineEmerging Challenges of ManagementShashank SatyajitamNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Prelim 1Documento3 pagineIndustrial Prelim 1KASHISH KRISHNA YADAVNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult Learning Class Learning ContractDocumento2 pagineAdult Learning Class Learning ContractEric M. LarsonNessuna valutazione finora