Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Pediatric Pain Assessment in T

Caricato da

nurtiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pediatric Pain Assessment in T

Caricato da

nurtiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pediatric Pain Assessment

In the Emergency Department: A Nursing

Evidence-Based Practice Protocol

Michele Habich and MariJo Letizia

D

espite the presence of pub-

lished evidence-based stan- Background: Many children present to the emergency department (ED) in pain

dards of care specific to pain and/or experience pain as a result of interventions necessary to manage their ill-

assessment and manage- ness. Pediatric pain assessment and management is complex and challenging.

ment, pediatric patients are inconsis- Despite the presence of published standards of care specific to pain assessment

tently and/or inappropriately assessed and management, nurses in the ED may not know about and/or consistently use

for pain (Probst, Lyons, Leonard, & these evidence-based practices. In particular, pediatric patients are inconsistent-

Esposito, 2005). In particular, nurses ly and/or inappropriately assessed for pain in the ED.

in the emergency department (ED) Methods: The aim of this project was to make standard the utilization of evi-

may not know about and/or consis- dence-based practices regarding pediatric pain assessment in the ED at a com-

tently use these evidence-based prac- munity hospital. The purpose of this project was to develop, implement, and eval-

tices (LeMay et al., 2009). The aim of uate a pediatric pain education program and pain assessment protocol to

this project was to make standard the improve nurses’ knowledge and standardize care in a community hospital emer-

utilization of evidence-based practices gency department.

regarding pediatric pain assessment in Results: Seventy-eight ED nurses completed the education program, consisting

the ED at a community hospital. The of an online module with content addressing pediatric pain assessment and man-

use of a computer-based education agement, and then used the protocol. Education program evaluations were very

program and implementation of a positive. A statistically significant difference in the mean pre- and post-test scores

pediatric pain protocol were expected indicated significant learning gains among participants; strong reliability of this

to be an effective method to promote test was demonstrated. Sixty patient medical records were reviewed two weeks

after the educational program. Pain assessment at triage and use of an appro-

change in pediatric pain assessment

priate pain scale for all assessments were the most consistently used compo-

and management in the ED at this

nents of the protocol. A low percentage of protocol adherence was found regard-

facility. ing assessment of pain characteristics.

Conclusion: Significant improvements in nurses’ pain knowledge are demon-

Background strated via an education program. Implementation of a pain assessment protocol

Approximately 25 million chil- is one mechanism to standardize nursing practice with pediatric patients in the

ED setting.

dren, many with a symptom of pain,

visit the ED annually (Niska, Bhuiya,

& Xu, 2010). Despite the high fre- ed pain scale during their visit. Of published an education module on

quency of pain, pediatric patients are those, only 76% of patients had their Pediatric Pain Management in the ED.

often not appropriately assessed for pain documented at triage; only 80% A panel of experts across the state

pain in this setting (Drendel, Brosseau, of patients had documentation of updated this module (EMSC, 2013).

& Gorelick, 2006; LeMay et al., 2009; pain reassessment within one hour of The EMSC module target population

Probst et al., 2005). For example, in a pharmacologic and/or non-pharma- includes ED nurses, physicians, and

one investigation of over 120 EDs in cologic intervention. Likewise, in a organization leaders. While the EMSC

the state of Illinois, significant dispar- recent study, nurses documented their module has been in existence for a

ities were noted in nurses’ assessment assessment of pain in only 59% (n = number of years, the ED at the facility

of pediatric pain (Probst et al., 2005). 150) of pediatric ED patients (LeMay where this project was conducted had

Only 60% of patients (n = 923) were et al., 2009). not fully implemented its recommen-

evaluated by a nurse using an accept- In 2001, The Joint Commission dations.

established accreditation standards

specific to the recognition, identifica- Description of Methods

Michele Habich, DNP, APN/CNS, CPN, is a tion and treatment of pain (The Joint

Pediatric Clinical Nurse Specialist, Central Commission, 2011). The Joint Com- And Results

DuPage Hospital, Winfield, IL.

mission pain standards serve as the The purpose of this project was to

MariJo Letizia, PhD, APN/ANP-BC, FAANP, foundation for population-specific develop, implement, and evaluate a

is a Professor and Associate Dean, Master’s pain protocols. Using these as a guide, pediatric pain education program and

and DNP Programs, Loyola University the Illinois Emergency Medical Ser- pain assessment protocol to improve

Chicago School of Nursing, Chicago, IL. vices for Children (EMSC) (2002) nurses’ knowledge and standardize

198 PEDIATRIC NURSING/July-August 2015/Vol. 41/No. 4

care in a community hospital ED. The pharmacologic pain treatment, pa- atric pain-related continuing educa-

following patient, intervention, com- tient and family education, and pedi- tion.

parison, and outcome (PICO) ques- atric pain outcome measurement. Al- Nurses’ responses to the nursing

tion was posed: In the pediatric popu- though the primary focus of this proj- demographic questionnaire, pre-and

lation, does use of an education pro- ect was pain assessment, general pain post-test, and program evaluation

gram and implementation of an management principles were includ- were electronically extracted. Data

assessment protocol improve nurses’ ed in the education program to from the nursing demographic ques-

knowledge and standardize nurses’ demonstrate the assessment, inter- tionnaire were used to describe the

pain assessment practices in the ED? vention, and reassessment cycle. characteristics of participants. For the

A quasi-experimental design was used Measures and data analysis. The pre- and post-test, each multiple

to measure the effects of the educa- authors developed a 20-item multi- choice question had one best answer;

tion program and assessment proto- ple-choice pre- and post-test based points were assigned for correct selec-

col. The university and hospital upon the education program to meas- tion, and a total exam score was cal-

Institutional Review Board approved ure knowledge regarding module culated across all questions. Program

the project. A waiver of signed con- objectives. Test item construction was evaluations were measured by calcu-

sent was granted. evaluated by a doctorally prepared lating an overall score on ratings of

nursing faculty member and revised achievement of the objectives and

Setting and Sample accordingly. Following test item re- analyzing responses to the questions

The project setting was the ED, view, five nursing pain experts were regarding confidence in assessing

main adult and pediatric, at a nation- asked to critique the education mod- pediatric pain, effectiveness of the

ally recognized community hospital ule and evaluate pre- and post-test computer-based program, relevance

located in a suburb west of Chicago. questions. The experts included two of content, and resultant change in

The ED is a level II trauma center and advanced practice nurses with a spe- nursing practice.

is an approved site for pediatric emer- cialty in pediatric pain or general pain Nonparametric descriptive statis-

gency care of children of all ages by in hospitalized children and adults, a tics were used to analyze categorical

the Illinois Department of Public pediatric inpatient nurse with de- variables. Paired sample t-test was

Health. The main and pediatric EDs monstrated expertise in pediatric used to note differences between pre-

combined provide care for approxi- pain, the pediatric ED manager, and and post-test scores. Internal consis-

mately 20,000 patients under the age ED clinical educator with demonstrat- tency of the test was evaluated using

of 19 each year. Seventy-five percent ed pediatric ED expertise and an Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

of these patients are seen in the pedi- awareness of pain-related standards in Results. Findings are reported on

atric ED. When the pediatric ED is at this population. Test content validity three topics: demographics, test analy-

capacity or is closed, all pediatric pa- was assessed using the scale content sis, and program evaluation.

tients are triaged in the main ED. validity index average (S-CVI/Ave) Demographics. Eighty-two percent

Over 100 nurses staff the ED, working (Polit, Beck, & Owen, 2007). The S- (n = 63) of main ED nurses and 100%

a variety of shifts. The sample for this CVI/Ave was determined by comput- (n = 15) of pediatric ED nurses com-

project included all ED nurses and 60 ing the item-content validity index (I- pleted the education module and pre-

ED pediatric patient medical records. CVI) for each test question and calcu- and post-test. Seventy-six nurses com-

lating the average I-CVI across items pleted the nursing questionnaire and

Education Program (Polit et al., 2007). The lower limit of program evaluation. Eighty-eight per-

The EMSC module and support- acceptability for S-CVI/Ave was 0.80 cent (n = 58) of participants were less

ing literature stress the importance of (Davis, 1992). Adjustments to the test than 44 years of age, with the highest

routine nursing staff education specif- were made based on these data. percentage (35%, n = 27) between the

ic to pediatric pain assessment and A program evaluation and nurs- ages of 35 to 44. The bachelor’s degree

management (EMSC, 2013). This pro- ing characteristics questionnaire were was the highest level of education for

ject included the development of a also developed. Using a 1- to 4-point the majority of participants (71%, n =

40-minute education program to Likert rating scale, nurses were asked 54). The median range of ED years

communicate EMSC recommenda- to rate their perceptions of achieve- experience was between 4 and 9 years

tions and introduce the pediatric pain ment of each objective and confi- (27%, n=21). Over half (n = 43) of all

assessment protocol. The education dence in assessing and managing participating nurses reported previous

program consisted of a pre- and post- pediatric pain. Additionally, nurses participation in a pediatric pain-relat-

test, narrated education module, were asked (using a yes/no response) ed continuing education activity

demographic and professional charac- if the computer-based program was either at work or outside of work with

teristic questionnaire, and program effective to deliver the information the last year. Of note, approximately

evaluation. Using the hospital’s elec- relevant to practice, and if they 20% (n = 15) had never participated

tronic learning management system, expect to change their practice as a in such continuing education activity.

the program was made available to all result from learning/understanding Test analysis. Internal consistency

nurses employed in the main and the content. The nursing question- of the 20-item post-test was evaluated

pediatric EDs. naire solicited the following demo- using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient

The education module included graphic and professional characteris- (0.95). The test demonstrates excel-

standardized content in the following tics of participants: age, nursing edu- lent internal consistency of each test

areas: pediatric pain assessment and cational background, years of ED question. Each of the 20 test ques-

management barriers, methods of nursing experience, specific ED loca- tions were found to be quite relevant

developmentally appropriate pain tion (i.e., main or pediatrics), and or highly relevant to the education

assessment, non-pharmacologic and time since last participation in pedi- module content I-CVI = 1.00 for each

PEDIATRIC NURSING/July-August 2015/Vol. 41/No. 4 199

Pediatric Pain Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Protocol

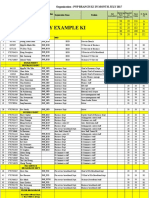

Figure 1.

Pediatric Pain Emergency Department Assessment Protocol

Pain assessment frequency. • Assess for the presence of pain in triage. May defer due to critical condition.

• Pain reassessment within one hour of pain-relieving non-pharmacologic and/or

pharmacologic intervention.

• Patients determined to have pain during the ED visit will be assessed for pain within 30

minutes of discharge.

Utilize an appropriate • N-PASS will be used to assess pain in infants less than 3 months.

standardized pediatric pain scale • The r-FLACC scale will be used to assess pain in children ages 3 months to 3 years,

with each pain assessment. cognitively impaired children, and those unable to utilize a subjective scale due to clinical

condition.

• The Wong-Baker Faces will be used to assess pain in children age 3 and older

• The visual analogue scale will be used to assess pain in the child ages 8 and older.

Ask the patient to identify the • Ask the toddler and preschool patient if they “hurt” or have an “owie” and ask them to

location (all assessments) and point or tell you where it hurts.

characteristics (triage only) of • Ask the school age and adolescent patient if they have pain.

the pain. – If they report pain ask about additional pain descriptors including: location, onset

(“When did the pain start?”), progression (“What makes the pain worse and what

makes the pain better?”), quality (“Are there words to describe your pain?), and effect

on daily activities (Does the pain stop you from doing things you normally do?”).

Documentation. • Type of pain assessment scale used with each assessment and pain score.

• Location of pain and additional pain characteristics such as onset, progression quality,

and effect on daily activities as appropriate.

N-PASS It is important to observe the infant for approximately 5 minutes before scoring each category. Score each cate-

gory and add each score to determine pain score. Sedation specific criteria will not be scored. Total from 0 to 10.

r-FLACC Observe patient for at least 1 to 3 minutes (5 minutes if asleep). Score each category and add each score to

determine pain score. Total from 0 to 10. Includes common pain expressive behaviors seen in cognitively

impaired. Can be individualized.

FACES Explain that each face is for a person who has no pain (hurt) or some, or a lot of pain (0 to 10). Ask the patient to

point to the face that best describes their pain.

VAS On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is “no pain” and 10 is the “worst pain” ask the patient to point or state the num-

ber that best describes their pain.

Sources: Hummel, Puchalski, Greech, & Weiss, 2008; Illinois Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC), 2013; Malviya,

Voepel-Lewis, Burke, Merkel, & Tait, 2006; Stinton, Kavanagh, Yamada, Gill, & Stevens, 2006; Wong & Baker, 1988.

question. The S-CVI/Ave was 1.00, program was effective in delivering be done within 30 minutes prior to

demonstrating acceptable test con- the content. Ninety-six percent (n = discharge from the ED (EMSC, 2013).

tent validity. 73) noted that the content was direct- Of note, the initial pain assessment

Each of the 20 multiple choice ly relevant to their nursing practice was to be deferred due to critical

questions had one best answer; points and that they desired to change their patient conditions requiring emer-

were assigned for correct selection and practice as a result of this program gent resuscitation such as hemody-

a total exam score was calculated (78%, n = 59). namic instability, acute airway or res-

across all questions. The pre-test scores piratory compromise, potentially

ranged from 15% to 85% (M = 56.8; SD Pain Assessment Protocol lethal arrhythmias, or the cumulative

= 13.7). The post-test scores ranged Development effects of multiple organ dysfunc-

from 15% to 90% (M = 69.4; SD = The pain assessment protocol tions.

15.9). On average, post-test scores were included four components: frequency A cognitively and clinically ap-

found to have a statistically significant of pain assessment by the nurse, selec- propriate pain assessment scale was to

increase of 12.6% higher than the pre- tion of pain assessment scale, assess- be used for each pain assessment

test (t = 6.63, df = 78, p = 0.000). ment of pain location and character- (Cohen et al., 2008, EMSC, 2013;

Program evaluation. The majority istics, and frequency of pain-related Stinton, Kavanagh, Yamada, Gill, &

of the participants reported that the documentation (see Figure 1). Accord- Stevens, 2006). Nurses used one of

education program objectives were ing to current standards, pain was to four standardized pediatric pain as-

met to a moderate or great extent. be assessed in all pediatric patients in sessment scales: 1) Neonatal Pain,

Fifty-four percent (n = 41) felt confi- triage within one hour of pain-reliev- Agitation, and Sedation Scale (N-

dent in assessing pediatric pain after ing intervention, and in the event the PASS); 2) revised Faces, Legs, Arms,

the program. The majority (88%, n = patient experienced pain during the Cry, and Consolability scale (r-

67) reported that the computer-based visit, an additional assessment was to FLACC); 3) Wong-Baker FACES; and 4)

200 PEDIATRIC NURSING/July-August 2015/Vol. 41/No. 4

visual analogue scale. These scales additional 8% (n = 5) had gastroin- resources department was not identi-

have demonstrated strong psychome- testinal conditions, including gastro- fied as a key stakeholder related to the

tric properties in the acute care setting enteritis, constipation, and acid indi- timing of the education program. A

(American Medical Association, 2010; gestion. The remaining 6% (n = 4) had number of hospital-wide human

Bailey, Bergerson, Gravel, & Daoust, general skin conditions. resources electronic learning assign-

2007; Duhn & Medves, 2004; Garra et The primary author reviewed a ments occurred concurrently with this

al., 2010; Hummel, Lawlor-Klean, & total of 60 patient records. Eighty- education program. The abundance of

Weiss, 2010; Malviya, Voepel-Lewis, seven percent (n = 52) of patients had assignments at the same time may

Burke, Merkel, & Tait, 2006; Niska et documentation of pain assessment at have contributed to the overall pro-

al., 2010; Stinton et al., 2006; Voepel- triage. Sixty-five percent (n = 34) of gram completion of only 75%.

Lewis, Zanotti, Dammeyer, & Merkel, patients had documentation of pain, Lower-than-expected pre-test

2010). In addition to indicating their with a pain score greater than or scores may be a result of variability of

current level of pain, pre-school chil- equal to one, at some time during pediatric pain content across schools

dren, school-age children, and adoles- their visit. However, only 32% (n = of nursing and participation in rou-

cents were asked to identify the loca- 11) of patients with documented pain tine pediatric pain-related continuing

tion of pain (EMSC, 2013). During the received a pharmacologic or non- education. Although a significant in-

triage pain assessment, school-age pharmacologic intervention for pain. crease in post-test scores is evident,

children and adolescents were asked Of those, 45% (n = 6) had documenta- these scores were also lower than

to describe pain onset (“When did the tion of pain reassessment within one expected given the participant-report-

pain start?”), progression (“What hour of the intervention. Forty-seven ed outstanding achievement of pro-

makes the pain worse and what makes percent (n = 16) of patients with pain gram objectives and confidence in

the pain better?”), quality (“Are there had documentation of pain assess- assessing pediatric pain after program

words to describe your pain?”), and ment within 30 minutes of discharge completion.

effect on daily activities (“Does the from the ED. Overall, 88% (n = 66) of The high percentage of patients

pain stop you from doing things you all pain assessments at triage, post- assessed for pain using an appropriate

normally do?”) (EMSC, 2013). The ED intervention, and prior to discharge scale demonstrates nurses’ under-

electronic medical record (EMR) con- were documented using an appropri- standing of the unique developmen-

tained the FLACC, Wong-Baker ate pain scale and included a pain tal and cognitive implications for

FACES. and visual analogue scale. The score. When the N-PASS or r-FLACC pediatric pain assessment. This was

EMR was revised to include the N- was used, all scale components were especially impressive as the protocol

PASS and r-FLACC scales with dedicat- scored 100% (n = 33) of the time. Pain included the addition of the two new

ed documentation rows for pain loca- location was documented in 56% (n = pain assessment scales. Although

tion, onset, progression, quality, and 20) of pain assessments. At triage, nurses in this ED demonstrated

effect on daily activities. 24% (n = 4) of school-age children increased knowledge, overall comfort

Measures and data analysis. and adolescents had documentation in pediatric pain assessment, and a

EMR data collection began following of pain quality, 29% (n = 5) pain favorable desire to incorporate new

nursing staff completion of the educa- onset, and 12% (n = 2) pain progres- pain knowledge from this program

tion program and continued for a sion. None of these patients had doc- into practice, the EMR review high-

total of two weeks. Data collected umentation of pain effects on daily lighted variability in actual adherence

through the EMR review included activities in triage. Pain assessment at to practice, including 1) adherence to

patient demographics and nurses’ triage and use of an appropriate pain use of correct pain scale, 2) adherence

pain-related documentation. Non- scale for all assessments represent the to pain assessment at triage, 3) non-

parametric descriptive statistics was most consistently used components adherence to documentation of pain

used to describe patient characteris- of the protocol. In contrast, assess- location and additional pain charac-

tics and nurses’ adherence to the pain ment of additional pain-related char- teristics, and 4) non-adherence to

assessment protocol. acteristics represented the lowest per- pain assessment post-intervention

Results. Patient ages ranged from centage of protocol adherence. and prior to discharge from the ED.

10 days to 16 years. Fifty-eight per- Although many patients had pain,

cent (n = 35) of the patients were Discussion and Nursing defined as pain score greater than or

males. The majority of the patients equal to one, few received an interven-

(67%, n = 40) received care in the Implications tion for pain. This project did not

pediatric ED. Thirty-three percent (n = This project provided a mecha- include recommendations for the

20) of patients presented post-injury nism to deliver evidence-based pedi- selection of pharmacologic or non-

with the following diagnoses: contu- atric pain assessment and manage- pharmacologic intervention based on

sion, laceration, sprain, fracture, abra- ment education to all ED nursing the severity of pain. As a result of this

sion, and closed head injury. An addi- staff. This project also included the project limitation, it is possible some

tional 33% (n = 20) had infectious implementation of a pediatric pain patients did not receive intervention

diagnoses including: fever, viral ill- assessment protocol and measure- due to low pain severity or lack of

ness, otitis media, pharyngitis, uri- ment of nurses’ medical record docu- pharmacologic orders. It is also possi-

nary tract infection, and cellulitis. Ten mentation to evaluate adherence to ble that nurses did use, but did not

percent (n = 6) presented with local- identified practices. document, non-pharmacologic inter-

ized pain of the abdomen, head, or This education program offering ventions. Further exploration is need-

extremity. Respiratory diagnoses, was carefully planned to support ed to evaluate nursing and physician

such as pneumonia, croup, and bron- staff’s completion of the program. specific pain management practices in

chiolitis, was present in 8% (n = 5). An Unfortunately, the hospital’s human this department. Nurses’ low adher-

PEDIATRIC NURSING/July-August 2015/Vol. 41/No. 4 201

Pediatric Pain Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Protocol

ence to post-intervention and pre-dis- Cohen, L., Lemanek, K., Blount, R., Dahlquist, LeMay, S., Johnston, C., Choiniere, M., Fortin,

charge protocol assessments needs fur- L., Lim, C., Palmero, T., ... Weiss, K. C., Kudirka, D., Murray, L., & Chlaut, D.

(2008). Evidence-based assessment of (2009). Pain Management Practices in a

ther exploration. The addition of miss-

pediatric pain. Journal of Pediatric Psy- Pediatric Emergency Room (PAMPER)

ing documentation alerts in the EMR chology, 33(9), 939-955. doi:10.1093/ study: Interventions with nurses. Pediatric

may be useful to remind nurses of the jpepsy/jsm103 Emergency Care, 25(8), 498-503.

need to document reassessment of Davis, L. (1992). Instrument review: Getting Malviya, S., Voepel-Lewis, T., Burke, C.,

pain following pain intervention. The the most from a panel of experts. Applied Merkel, S., & Tait, A. (2006). The revised

inclusion of pain assessment in routine Nursing Research, 5, 194-197. FLACC observational pain tool: Improved

Drendel, A., Brousseau, D., & Gorelick, M. reliability and validity for pain assessment

pre-discharge vital signs may also (2006). Pain assessment for pediatric in children with cognitive impairment.

increase nurses’ adherence. patients in the emergency department. Pediatric Anaesthesia, 16(3), 258-265.

Of interest, the highest percent- Pediatrics, 117(5), 1511-1518. doi:10.111/j.14609592.2005.01773.x

age of pain location documentation doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2046 Niska, R., Bhuiya, F., & Xu, J. (2010). National

occurred in triage. It may be assumed Duhn, L., & Medves, J. (2004). A systematic ambulatory medical care survey: 2007

integrative review of infant pain assess- emergency department summary. Re-

that pain location remains constant, ment tools. Advances in Neonatal Care, trieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

unless otherwise indicated, for the 4(3), 126-140. doi: ahcd/ahcd_reports.htm#Emergency

remainder of the visit thus subse- 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.04.005 Polit, D., Beck, C., & Owen, S. (2007). Is the

quent documentation of pain loca- Garra, G., Singer, A.J., Taira, B.R., Chohan, J., CVI an acceptable indicator of content

tion was lacking. Few patients had Cardoz, H., ... Thode, H.C., Jr. (2010). validity? Appraisal and recommenda-

Validation of the Wong-Baker FACES tions. Research in Nursing & Health, 30,

documentation of additional pain pain rating scale in pediatric emergency 459-467.

characteristics. Although these prac- department patients. Academic Emer- Probst, B., Lyons, E., Leonard, D., & Esposito,

tices were recommended by EMSC, gency Medicine, 17(1), 50-54. doi:10. T. (2005). Factors affecting emergency

further assessment is needed to deter- 1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00620.x department assessment and manage-

mine barriers to use in this ED. Hummel, P., Puchalski, M., Greech, S., & ment of pain in children. Pediatric

Weiss, M. (2008). Clinical reliability and Emergency Care, 21(5), 298-305.

validity of the N-PASS: Neonatal pain, Stinton, J., Kavanagh, T., Yamada, J., Gill, N.,

Conclusion agitation and sedation scale with pro- & Stevens, B. (2006). Systematic review

longed pain. Journal of Perinatology, of the psychometric properties, inter-

The importance of improving 28(1), 55-60. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.721186 pretability and feasibility of self-report

pediatric pain assessment has been Hummel, P., Lawlor-Klean, P., & Weiss, M. pain intensity measures for use in clinical

well documented in the literature. (2010). Validity and reliability of the N- trials in children and adolescents. Pain,

PASS assessment tool with acute pain. 125(12), 143-157.

Nurses’ are primarily responsible for Journal of Perinatology, 30(7), 474-478. The Joint Commission. (2011). Hospital

assessing pain and response to inter- doi:10.1038/jp.2009.185 accreditation standards. Oakbrook: Joint

ventions in the ED patient. Signi- Illinois Emergency Medical Services for Commission Resources.

ficant improvements in nurses’ pain Children (EMSC). (2002). Pediatric pain Voepel-Lewis, T., Zanotti, J., Dammeyer, J., &

knowledge can be achieved through a management in the emergency setting: Merkel, S. (2010). Reliability and validity

Online education module. Retrieved from of the faces, legs, activity, cry, consolabil-

computer-based education program. http://www. luhs.org/depts/emsc/pain ity behavioral tool in assessing acute pain

Translating this knowledge to practice _web_info_9_2002.htm in critically ill patients. American Journal

can then occur, as presented in Figure Illinois Emergency Medical Services for of Critical Care, 19(1), 55-61. doi:10.

1, via the implementation of a pain Children (EMSC). (2013). Pediatric pain 4037/ajcc2010624

assessment protocol. Together these management in the emergency setting: Wong, D., & Baker, C. (1988). Pain in children:

Online education module. Retrieved Comparison of assessment scales.

serve as a platform for optimal care March 1, 2013, from http://www.public Pediatric Nursing, 14(1), 9-17.

delivery. However, education and healthlearning.com/login/index.php

availability of practice standards

alone may not translate to actual im-

provement in care delivered by nurs-

es. Exploration of factors contributing

to nurses’ decisions to use new pedi-

atric pain-related knowledge in prac-

tice must be explored and addressed.

Further, ongoing quality measure-

ment will provide a mechanism to

sustain this project over time. Ap-

propriate identification and docu-

mentation of pain is the first step in

successful pain management.

References

American Medical Association (AMA). (2010).

Pediatric pain management. Retrieved

from http://www.ama-cmeonline.com/

pain_mgmt/print version/ama_pain

mgmt_m6.pdf

Bailey, B., Bergeron, S., Gravel, J., & Daoust,

R. (2007). Comparison of four pain

scales in children with acute abdominal

pain in a pediatric emergency depart-

ment. Annals of Emergency Medicine,

50(4), 379-383.

202 PEDIATRIC NURSING/July-August 2015/Vol. 41/No. 4

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Ethical Conflicts in Psychology PDF DownloadDocumento2 pagineEthical Conflicts in Psychology PDF DownloadAvory0% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Stonehell Dungeon 1 Down Night Haunted Halls (LL)Documento138 pagineStonehell Dungeon 1 Down Night Haunted Halls (LL)some dude100% (9)

- PNP Ki in July-2017 AdminDocumento21 paginePNP Ki in July-2017 AdminSina NeouNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Network Unit 6 - UCDocumento15 pagineData Network Unit 6 - UCANISHA DONDENessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 1Documento11 pagineContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 1JUN GERONANessuna valutazione finora

- Unbound DNS Server Tutorial at CalomelDocumento25 pagineUnbound DNS Server Tutorial at CalomelPradyumna Singh RathoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Week - 2 Lab - 1 - Part I Lab Aim: Basic Programming Concepts, Python InstallationDocumento13 pagineWeek - 2 Lab - 1 - Part I Lab Aim: Basic Programming Concepts, Python InstallationSahil Shah100% (1)

- Eapp Melc 12Documento31 pagineEapp Melc 12Christian Joseph HerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Marine Cargo InsuranceDocumento72 pagineMarine Cargo InsuranceKhanh Duyen Nguyen HuynhNessuna valutazione finora

- SavannahHarbor5R Restoration Plan 11 10 2015Documento119 pagineSavannahHarbor5R Restoration Plan 11 10 2015siamak dadashzadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Truss-Design 18mDocumento6 pagineTruss-Design 18mARSENessuna valutazione finora

- Enzymes IntroDocumento33 pagineEnzymes IntropragyasimsNessuna valutazione finora

- Algorithms For Automatic Modulation Recognition of Communication Signals-Asoke K, Nandi, E.E AzzouzDocumento6 pagineAlgorithms For Automatic Modulation Recognition of Communication Signals-Asoke K, Nandi, E.E AzzouzGONGNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Electronics Chapter 5Documento30 pagineDigital Electronics Chapter 5Pious TraderNessuna valutazione finora

- The Comma Rules Conversion 15 SlidesDocumento15 pagineThe Comma Rules Conversion 15 SlidesToh Choon HongNessuna valutazione finora

- Green Dot ExtractDocumento25 pagineGreen Dot ExtractAllen & UnwinNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Add Attachment Using JAVA MappingDocumento4 pagineHow To Add Attachment Using JAVA MappingmvrooyenNessuna valutazione finora

- KCG-2001I Service ManualDocumento5 pagineKCG-2001I Service ManualPatrick BouffardNessuna valutazione finora

- Aribah Ahmed CertificateDocumento2 pagineAribah Ahmed CertificateBahadur AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing Micro and Macro EnvironmentDocumento8 pagineMarketing Micro and Macro EnvironmentSumit Acharya100% (1)

- Barrett Beyond Psychometrics 2003 AugmentedDocumento34 pagineBarrett Beyond Psychometrics 2003 AugmentedRoy Umaña CarrilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Spectacle Blinds - Closed Blinds Open Blinds (Ring Spacer)Documento2 pagineSpectacle Blinds - Closed Blinds Open Blinds (Ring Spacer)Widiyanto WiwidNessuna valutazione finora

- CTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Documento45 pagineCTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Resort1.7 Mri100% (1)

- A Literary Nightmare, by Mark Twain (1876)Documento5 pagineA Literary Nightmare, by Mark Twain (1876)skanzeniNessuna valutazione finora

- Neet Question Paper 2019 Code r3Documento27 pagineNeet Question Paper 2019 Code r3Deev SoniNessuna valutazione finora

- 105 2Documento17 pagine105 2Diego TobrNessuna valutazione finora

- Extract The .Msi FilesDocumento2 pagineExtract The .Msi FilesvladimirNessuna valutazione finora

- Adaptive Leadership: Leadership: Theory and PracticeDocumento14 pagineAdaptive Leadership: Leadership: Theory and PracticeJose Daniel Quintero100% (1)

- RN42Documento26 pagineRN42tenminute1000Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Test Level 7 New Format 2019Documento3 pagineFinal Test Level 7 New Format 2019fabian serranoNessuna valutazione finora