Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

FraudK. Jeganathan Vs Union of India On 21 April, 2008

Caricato da

maazmrdarDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

FraudK. Jeganathan Vs Union of India On 21 April, 2008

Caricato da

maazmrdarCopyright:

Formati disponibili

K.

Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

Madras High Court

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS

Dated 21..4..2008

Coram:

The Hon'ble Mr. Justice K.CHANDRU

W.P. No. 8886 of 1998

K. Jeganathan .. Petitioner

vs.

1. Union of India

Rep. by Director General Border Roads

Kashmir House

DHQPO

New Delhi

2. The Chief Engineer

Project Vartak

C/o 99 A.P.O.

Tezpur

Assam District .. Respondents

Petition filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India seeking for issuance of writ of C

For Petitioner : Mr. C. Sundaravadivel

For Respondents : Mr. M. Dhamodharan

O R D E R

Heard the arguments of the learned counsel for the parties and have perused the records.

2. The petitioner was appointed as a Pioneer in the GREF on 21.7.1966. Subsequently, he was

promoted as a Store man w.e.f. 15.9.1968. Thereafter, through the selection made by the

Departmental promotion Committee (DPC), he was promoted as Store Keeper (Technical) at the

Eastern Store Division, GREF, Tezpur in Assam on 18.7.1983. He was given a charge-memo dated

29.6.1990 stating that the H.S.L.C. Examination Certificate produced by him was not genuine and

with that fake certificate, he had unjustly obtained promotion. He had also violated Rule 3(1)(i) and

(iii) of the Central Services Conduct Rules, 1964.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 1

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

3. An enquiry was conducted against the petitioner and he was given full opportunity to defend

himself. He neither gave any written statement in the enquiry nor made any oral submission. The

defence witness named by him confirmed that the H.S.L.C. Certificate produced by him was not

genuine and was not issued by the Board of Secondary Education, Manipur. The Enquiry Officer

found him guilty and copy of the report was furnished to him. Thereafter, he was imposed with a

punishment of dismissal from service by the second respondent vide his order dated 17.3.1997. An

appeal was filed by the petitioner which was rejected by the first respondent vide order dated

20.7.1997.

4. It must be stated in the enquiry, the letter dated 30.7.1992 issued by the Headmaster of Bhairodin

Hindi High School, Impal, was produced wherein the Department was informed that his school was

a Hindi Medium School and they would not have admitted any Tamil Medium scholar like the

petitioner. Further, the letter dated 20.12.1999 written by the Secretary, Board of Secondary

Education, Manipur that the petitioner had never appeared at the H.S.L.C. Examination in the year

1984 with Roll No. 7359 was also produced in the enquiry. It was on the strength of these materials,

the petitioner was found guilty in the departmental enquiry.

5. Learned counsel for the petitioner submitted that the enquiry conducted against him was vitiated

and many of the witnesses, whose names were furnished in the charge-memo, were not summoned.

He also submitted that he has not committed any misconduct in as much as the certificate produced

by him was genuine and the statements issued by the Headmaster and the Secretary of Board of

H.S.C., Manipur were not proved in the manner known to law. In any event, he had submitted that

the requirement of an H.S.L.C. Pass is relevant only for the promoted post and, therefore, he must

be allowed to continue in service at least in the lower post for which he was not disqualified. Finally,

he submitted that having worked for 31 years, leniency must be shown to him.

6. With reference to the submission that the enquiry was not fair and the report of the Secretary,

H.S.C. Board, Manipur, should not be believed, it is relevant to refer to some decisions of this Court

and the Supreme Court.

6.1. In this context, the Supreme Court vide its decision in Maharashtra State Board of Secondary

and Higher Secondary Education v. K.S. Gandhi and others [(1991) 2 SCC 716] has held that the

principles of natural justice will depend on the nature of inquiry and the peculiar circumstances of

each case. The relevant passage found in paragraph 17 may be usefully extracted below :-

Para 17: "..... The show cause notice furnished wealth of material particulars on which the tampering

was alleged to be founded and gave the opportunity to each student to submit the explanation and

also to adduce evidence, oral or documentary at the inquiry. Each student submitted the explanation

denying the allegation...."

6.2. Further, in identical circumstances, a Division Bench of this Court in W.P. No. 19063 of 2004

[P. Sekar v. The Registrar, Tamil Nadu Administrative Tribunal, Chennai and others], disposed on

16.02.2008, has held as follows:-

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 2

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

Para 5: "Therefore, the contention of the petitioner that the enquiry report and the order of

punishment are based on no evidence is not acceptable. In a departmental enquiry, technical rules

of the Evidence Act are not strictly applicable. On behalf of the Department, the letter of the

Director of Government Examinations dated 7.11.2001 had been produced indicating that the marks

reflected in the mark sheet submitted by the petitioner did not tally with the marks available from

the original records. The petitioner himself was examined during the departmental enquiry and the

questions put and the answers given are available on record. Except baldly stating that the petitioner

has got mark sheet from the school, there is no other acceptable material or detail has been given. It

is not even the case of the petitioner that he had actually passed and the report given by the Director

of the Government Examinations is incorrect. Since the petitioner had submitted a mark sheet,

which was found to be incorrect, it was within the subject knowledge of the petitioner as to the

source of obtaining such mark sheet and it was for him to explain such aspect by adducing proper

evidence. To that extent, the Tribunal was correct in coming to the conclusion that the charge has

been found against him."

7. The Supreme Court in many of its decisions, had answered the issue as to whether leniency can be

shown by Courts in cases of persons who gave fake forged educational certificates at the time of

appointment and securing employment by fraud or deceit. Some of the decisions were also rendered

in the context of persons gaining entry with false Community Certificates.

7.1. In Bank of India v. Avinash D. Mandivikar [(2005) 7 SCC 690], the Supreme has held in

paragraphs 11 and 12 as follows:

Para 11: ".... Fraud and collusion vitiate even the most solemn proceedings in any civilised system of

jurisprudence. This Court in Bhaurao Dagdu Paralkar v. State of Maharashtra dealt with the effect of

fraud. It was held as follows in the said judgment: (2005 (7) SCC pp. 613-14, paras 12-16) ™2.

Fraud is proved when it is shown that a false representation has been made (i) knowingly, or (ii)

without belief in its truth, or (iii) recklessly, careless whether it be true or false. * * *

13. This aspect of the matter has been considered by this Court in Roshan Deen v. Preeti Lal (2002

(1) SCC 100), Ram Preeti Yadav v. U.P. Board of High School and Intermediate Education (2003 (8)

SCC 311), Ram Chandra Singh case (2003 (8) SCC 319) and Ashok Leyland Ltd. v. State of T.N.

(2004 (3) SCC 1).

14. Suppression of a material document would also amount to a fraud on the court. (See

Gowrishankar v. Joshi Amba Shankar Family Trust (1996 (3) SCC 1) and S.P. Chengalvaraya Naidu

case (1994 (1) SCC 1).)

15. Fraud is a conduct either by letter or words, which induces the other person or authority to

take a definite determinative stand as a response to the conduct of the former either by words or

letter. Although negligence is not fraud but it can be evidence on fraud; as observed in Ram Preeti

Yadav case.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 3

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

16. In Lazarus Estates Ltd. v. Beasley Lord Denning observed at QB pp. 712 and 713 : (All ER p.

345-C) (1956) 1 QB 702).

No judgment of a court, no order of a minister, can be allowed to stand if it has been obtained by

fraud. Fraud unravels everything. In the same judgment Lord Parker, L.J. observed that fraud

vitiates all transactions known to the law of however high a degree of solemnity. (p. 722) [19]. These

aspects were recently highlighted in State of A.P. v. T. Suryachandra Rao (2005 (6) SCC 149).

Therefore, mere delayed reference when the foundation for the same is alleged fraud does not in any

way affect the legality of the reference.

Para 12: "Looked at from any angle the High Court s judgment holding that Respondent 1 employee

was to be reinstated in the same post as originally held is clearly untenable. The order of termination

does not suffer from any infirmity and the High Court should not have interfered with it. By giving

protection for even a limited period, the result would be that a person who has a legitimate claim

shall be deprived the benefits. On the other hand, a person who has obtained it by illegitimate

means would continue to enjoy it notwithstanding the clear finding that he does not even have a

shadow of right even to be considered for appointment."

7.2. The Supreme Court in the decision in Ram Saran v. IG of Police, CRPF [(2006) 2 SCC 541]

observed in paragraphs 9 to 11 as follows:

Para 9: "In R. Vishwanatha Pillai v. State of Kerala it was observed as follows: (SCC pp. 116-17, para

19) ™9. It was then contended by Shri Ranjit Kumar, learned Senior Counsel for the appellant that

since the appellant has rendered about 27 years of service, the order of dismissal be substituted by

an order of compulsory retirement or removal from service to protect the pensionary benefits of the

appellant. We do not find any substance in this submission as well. The rights to salary, pension and

other service benefits are entirely statutory in nature in public service. The appellant obtained the

appointment against a post meant for a reserved candidate by producing a false caste certificate and

by playing a fraud. His appointment to the post was void and non est in the eye of the law. The right

to salary or pension after retirement flows from a valid and legal appointment. The consequential

right of pension and monetary benefits can be given only if the appointment was valid and legal.

Such benefits cannot be given in a case where the appointment was found to have been obtained

fraudulently and rested on a false caste certificate. A person who entered the service by producing a

false caste certificate and obtained appointment for the post meant for a Scheduled Caste, thus

depriving a genuine Scheduled Caste candidate of appointment to that post, does not deserve any

sympathy or indulgence of this Court. A person who seeks equity must come with clean hands. He,

who comes to the court with false claims, cannot plead equity nor would the court be justified to

exercise equity jurisdiction in his favour. A person who seeks equity must act in a fair and equitable

manner. Equity jurisdiction cannot be exercised in the case of a person who got the appointment on

the basis of a false caste certificate by playing a fraud. No sympathy and equitable consideration can

come to his rescue. We are of the view that equity or compassion cannot be allowed to bend the

arms of law in a case where an individual acquired a status by practising fraud. Para 10: Though

the case related to a false [caste] certificate, the logic indicated clearly applies to the present case.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 4

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

Para 11: This is a case which does not deserve any leniency otherwise it would be giving premium to

a person who admittedly committed forgery. In the instruction (GO No. 29 of 1993), it has been

provided that whenever it is found that a government servant who was not qualified or eligible in

terms of the recruitment rules, etc. for initial recruitment in service or had furnished false

information or produced a false certificate in order to secure appointment should not be retained in

service. After inquiry as provided in Rule 14 of the CCS(CCA) Rules, 1965 if the charges are proved,

the government servant should be removed or dismissed from service and under no circumstances

any other penalty should be imposed."

7.3. Further, the Supreme Court in the decision in Superintendent of Post Offices v. R. Valasina

Babu [(2007) 2 SCC 335] observed in paragraphs 14 and 15 as follows:

Para 14: "The question in regard to the effect of obtaining appointment by producing false certificate

came up for consideration in State of Maharashtra v. Ravi Prakash Babulalsing Parmar wherein this

Court opined that the authorities concerned would have jurisdiction to go into the said question and

pass an appropriate order. The effect of cancellation of such caste certificate had also been noticed

in the light of a two-Judge Bench decision of this Court in Bank of India v. Avinash D. Mandivikar

wherein it was held that if the employee concerned had played fraud in obtaining an appointment,

he should not be allowed to get the benefits thereof, as the foundation of appointment collapses.

Para 15: In this view of the matter, we are of the opinion that in a case of this nature, it might not

have been necessary to initiate any disciplinary proceeding against the respondent."

7.4. In Additional General Manager Human Resource, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited v. Suresh

Ramkrishna Burde [(2007) 5 SCC 336] once again reiterated the principles laid down in R.

Viswanatha Pillai v. State of Kerala [(2007) 5 SCC 336] and the following passage found in

paragraph 10 may be usefully extracted:

Para 10: "An identical controversy was again examined in R. Vishwanatha Pillai v. State of Kerala

which is a decision rendered by a Bench of three learned Judges. The employee in the aforesaid case

had got an appointment in the year 1973 against a post reserved for Scheduled Caste. On complaint,

the matter was enquired into and the Scrutiny Committee vide its order dated 18-11-1995 held that

he did not belong to Scheduled Caste and the challenge raised to the said order was rejected by the

High Court and the special leave petition filed against the said order was also dismissed by this

Court. He then filed a petition before the Administrative Tribunal praying for a direction not to

terminate his services which was allowed, but the order was reversed by the High Court in a writ

petition. The employee then filed an appeal in this Court. After a detailed consideration of the

matter this Court dismissed the appeal and para 15 of the Report, which is relevant for the decision

of the present case, is reproduced below: (SCC p. 115) ™5. This apart, the appellant obtained the

appointment in the service on the basis that he belonged to a Scheduled Caste community. When it

was found by the Scrutiny Committee that he did not belong to the Scheduled Caste community,

then the very basis of his appointment was taken away. His appointment was no appointment in the

eye of the law. He cannot claim a right to the post as he had usurped the post meant for a reserved

candidate by playing a fraud and producing a false caste certificate. Unless the appellant can lay a

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 5

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

claim to the post on the basis of his appointment he cannot claim the constitutional guarantee given

under Article 311 of the Constitution. As he had obtained the appointment on the basis of a false

caste certificate he cannot be considered to be a person who holds a post within the meaning of

Article 311 of the Constitution of India. Finding recorded by the Scrutiny Committee that the

appellant got the appointment on the basis of a false caste certificate has become final. The position,

therefore, is that the appellant has usurped the post which should have gone to a member of the

Scheduled Castes. In view of the finding recorded by the Scrutiny Committee and upheld up to this

Court, he has disqualified himself to hold the post. The appointment was void from its inception.

In the light of the above discussion, the contentions made by the learned counsel for the petitioner

that the petitioner should be dealt with leniently must be rejected.

8. On the question that there is no misconduct, it is necessary to refer to the judgment of the

Supreme Court in Union of India v. J. Ahmed [1979 (2) SCC 286]. The following passages found in

paragraphs 9 and 11 of the judgment may be usefully extracted:

Para 9: "The words act or omission contemplated by Rule 4 of the Discipline and Appeal Rules

have to be understood in the context of the All India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1954 ( Conduct

Rules for short). The Government has prescribed by Conduct Rules a code of conduct for the

members of All India Services. Rule 3 is of a general nature which provides that every member of the

service shall at all times maintain absolute integrity and devotion to duty. Lack of integrity, if

proved, would undoubtedly entail penalty.... If Rule 3 were the only rule in the Conduct Rules it

would have been rather difficult to ascertain what constitutes misconduct in a given situation. But

Rules 4 to 18 of the Conduct Rules prescribe code of conduct for members of service and it can be

safely stated that an act or omission contrary to or in breach of prescribed rules of conduct would

constitute misconduct for disciplinary proceedings. This code of conduct being not exhaustive it

would not be prudent to say that only that act or omission would constitute misconduct for the

purpose of Discipline and Appeal Rules which is contrary to the various provisions in the Conduct

Rules. The inhibitions in the Conduct Rules clearly provide that an act or omission contrary thereto

so as to run counter to the expected code of conduct would certainly constitute misconduct. Some

other act or omission may as well constitute misconduct...."

[Emphasis added] Para 11: "Code of conduct as set out in the Conduct Rules clearly indicates the

conduct expected of a member of the service. It would follow that conduct which is blameworthy for

the government servant in the context of Conduct Rules would be misconduct. If a servant conducts

himself in a way inconsistent with due and faithful discharge of his duty in service, it is misconduct

(see Pierce v. Foster1). A disregard of an essential condition of the contract of service may constitute

misconduct [see Laws v. London Chronicle (Indicator Newspapers)]. This view was adopted in

Shardaprasad Onkarprasad Tiwari v. Divisional Superintendent, Central Railway, Nagpur Division,

Nagpur, and Satubha K. Vaghela v. Moosa Raza. The High Court has noted the definition of

misconduct in Stroud s Judicial Dictionary which runs as under:

Misconduct means, misconduct arising from ill motive; acts of negligence, errors of judgment, or

innocent mistake, do not constitute such misconduct.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 6

K. Jeganathan vs Union Of India on 21 April, 2008

9. The petitioner was charge-sheeted for the violation of Rule 3 of the C.C.S. Conduct Rules and the

lack of integrity on his part is clearly proved. The submission that the petitioner must be allowed to

continue in the lower post of Storeman is only stated to be rejected for the reasons already set out.

K.CHANDRU, J.

gri

10. In the light of the above, the writ petition fails and accordingly, will stand dismissed. No costs.

Index : Yes 21..4..2008

Internet : Yes

gri

To

1. Union of India

Rep. by Director General Border Roads

Kashmir House

DHQPO

New Delhi

2. The Chief Engineer

Project Vartak

C/o 99 A.P.O.

Tezpur

Assam District

W.P. No. 8886 of 1998

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1182189/ 7

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeDa EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- Chandrama Tewari Vs Union of India Through General On 18 November 1987Documento7 pagineChandrama Tewari Vs Union of India Through General On 18 November 1987anwa1Nessuna valutazione finora

- WP 6309 2006 FinalOrder 14-Sep-2022Documento24 pagineWP 6309 2006 FinalOrder 14-Sep-2022Sakshi ShettyNessuna valutazione finora

- Epuru Sudhakar and Ors Vs Govt of AP and OrsDocumento23 pagineEpuru Sudhakar and Ors Vs Govt of AP and OrsSakshi AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- At Ettumanoor Dated 18-05-2 Vs by Advs - Sri.k.gopalakrishna ... On 18 May, 2010Documento11 pagineAt Ettumanoor Dated 18-05-2 Vs by Advs - Sri.k.gopalakrishna ... On 18 May, 2010prayank jainNessuna valutazione finora

- EthicsDocumento17 pagineEthicskipkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Part IDocumento21 paginePart IVAISHNAVI P SNessuna valutazione finora

- Memorandum of CRPDocumento11 pagineMemorandum of CRPSathya narayananNessuna valutazione finora

- Krishna - Pathak - Vs - Vinod - Shankar - Tiwari - and - Ors - 2u050267COM108131 Issue Not Raised No ReviewDocumento10 pagineKrishna - Pathak - Vs - Vinod - Shankar - Tiwari - and - Ors - 2u050267COM108131 Issue Not Raised No ReviewApoorvnujsNessuna valutazione finora

- LATESTLAW - O623312GEHB65474319GJ43DRCZTS1LK9IWJODr. Subhash Kashinath Mahajan Vs The State of Maharashtra and Anr PDFDocumento89 pagineLATESTLAW - O623312GEHB65474319GJ43DRCZTS1LK9IWJODr. Subhash Kashinath Mahajan Vs The State of Maharashtra and Anr PDFANAND GEO 1850508Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mohan Chandra P V State of Karnataka 11 Nov 2022 444030Documento2 pagineMohan Chandra P V State of Karnataka 11 Nov 2022 444030SANTHOSH KUMAR T MNessuna valutazione finora

- Display PDFDocumento18 pagineDisplay PDFabhishekkomeNessuna valutazione finora

- Moot Problem 1 - Civil AppealDocumento9 pagineMoot Problem 1 - Civil AppealSIMRAN PRADHANNessuna valutazione finora

- 27 Supreme Court DecisionsDocumento600 pagine27 Supreme Court Decisionsfuck pakNessuna valutazione finora

- W.P.No.7284 of 2021Documento104 pagineW.P.No.7284 of 2021RepublicNessuna valutazione finora

- JudgmentDocumento35 pagineJudgmentraghul_sudheeshNessuna valutazione finora

- 50 Casesdocx KKKKDocumento38 pagine50 Casesdocx KKKKTanvi SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- B'edappadi K. Palaniswami Vs T.T.V. Dhinakaran On 7 February, 2019'Documento22 pagineB'edappadi K. Palaniswami Vs T.T.V. Dhinakaran On 7 February, 2019'sriprasadNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.1 CivilDocumento10 pagine1.1 CivilSIMRAN PRADHANNessuna valutazione finora

- Compilation of Judgments - Atul Kumar Garg WP PDFDocumento124 pagineCompilation of Judgments - Atul Kumar Garg WP PDFRajat TibrewalNessuna valutazione finora

- Dalip Singh vs. State of U.P. and Ors. (03.12.2009 - SC)Documento8 pagineDalip Singh vs. State of U.P. and Ors. (03.12.2009 - SC)Zalak ModyNessuna valutazione finora

- Satrucharla Vijaya Rama Raju v. Nimmaka Jaya Raju & Ors. - ManupatraDocumento10 pagineSatrucharla Vijaya Rama Raju v. Nimmaka Jaya Raju & Ors. - ManupatraSameer GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- In The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi: Date of Decision: February 07, 2020Documento4 pagineIn The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi: Date of Decision: February 07, 2020venugopal murthyNessuna valutazione finora

- 29.04.2020 Instances of Misconduct PDFDocumento13 pagine29.04.2020 Instances of Misconduct PDFjisha shajiNessuna valutazione finora

- K Vijaya Lakshmi Vs Govt of Andhra Pradesh Repress130142COM541774Documento13 pagineK Vijaya Lakshmi Vs Govt of Andhra Pradesh Repress130142COM541774Pranav KbNessuna valutazione finora

- Peddireddy OrderDocumento11 paginePeddireddy Ordermahis1980Nessuna valutazione finora

- CRLP 1154 2014Documento8 pagineCRLP 1154 2014Snig KavNessuna valutazione finora

- OrdjudDocumento15 pagineOrdjudDeepak KansalNessuna valutazione finora

- K Anbazhagan Vs The Superintendent of Police Ors On 18 November 2003Documento15 pagineK Anbazhagan Vs The Superintendent of Police Ors On 18 November 2003FionaNessuna valutazione finora

- Narayan Vs Sadanand and Ors 04092017 KARHCKA201715091715580994COM996308Documento7 pagineNarayan Vs Sadanand and Ors 04092017 KARHCKA201715091715580994COM996308utsavsinghofficeNessuna valutazione finora

- MR Shankar R Bhavani Vs State of KarnatakaDocumento4 pagineMR Shankar R Bhavani Vs State of KarnatakaDebashish Priyanka SinhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ayaaubkhan Noorkhan Pathan Vs State of Maharashtra Ors On 8 November 2012Documento16 pagineAyaaubkhan Noorkhan Pathan Vs State of Maharashtra Ors On 8 November 2012anwa1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Judgement 20-Mar-2018Documento89 pagine2017 Judgement 20-Mar-2018vakilchoubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sachidanand Singh Vs Indian Oil CorporationDocumento19 pagineSachidanand Singh Vs Indian Oil Corporationdayal automobilesNessuna valutazione finora

- LR When File 138Documento11 pagineLR When File 138Raja LingamNessuna valutazione finora

- The Registrar V Savukku Shankar and Others 435191Documento46 pagineThe Registrar V Savukku Shankar and Others 435191Rokesh NaiduNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Ethics Case Law Chandra Shekhar Soni Vs Bar Council of RajasthanDocumento10 pagineProfessional Ethics Case Law Chandra Shekhar Soni Vs Bar Council of RajasthanthanksNessuna valutazione finora

- Electronic Record or Computer Output-cannot Be Led in Evidence Unless Certificate, As Required by Section 65-B of Evidence Act is Filed-No Distinction of 'Primary' or 'Secondary' Evidence for Requirement of the cDocumento20 pagineElectronic Record or Computer Output-cannot Be Led in Evidence Unless Certificate, As Required by Section 65-B of Evidence Act is Filed-No Distinction of 'Primary' or 'Secondary' Evidence for Requirement of the cAnuj GoyalNessuna valutazione finora

- 50 CasesDocumento37 pagine50 CasesTales Of Tanvi100% (4)

- LaxmanDocumento9 pagineLaxmanSunil Kavaskar rNessuna valutazione finora

- PeejDocumento17 paginePeejkipkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics 2Documento27 pagineEthics 2kipkarNessuna valutazione finora

- WA 145 of 20121 Eluru CorporationDocumento12 pagineWA 145 of 20121 Eluru CorporationRamesh Babu TatapudiNessuna valutazione finora

- Acknowledgement: Professional Accounting System. The Success of This Project Is A Result of Sheer Hard WorkDocumento45 pagineAcknowledgement: Professional Accounting System. The Success of This Project Is A Result of Sheer Hard WorkKRISHAN LALLA XII BNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court of India: BenchDocumento16 pagineSupreme Court of India: BenchNidhi SalianNessuna valutazione finora

- Maibam Ibohal Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 02GH200904062119070665COM443482Documento6 pagineMaibam Ibohal Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 02GH200904062119070665COM443482Yug SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Kanwar Singh Saini VS High Court of DelhiDocumento10 pagineKanwar Singh Saini VS High Court of DelhiMukul RawalNessuna valutazione finora

- In The Gauhati High CourtDocumento12 pagineIn The Gauhati High CourtPradeepNessuna valutazione finora

- Appreciation of Evidence in Criminal Cases 2011 SCDocumento12 pagineAppreciation of Evidence in Criminal Cases 2011 SCSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್Nessuna valutazione finora

- Devendra Kumar V State of Uttaranchal - Service Law - Suppression of Material Information - Termination UpheldDocumento5 pagineDevendra Kumar V State of Uttaranchal - Service Law - Suppression of Material Information - Termination Upheldsankhlabharat100% (1)

- IOS2Documento32 pagineIOS2Vijaya SriNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 SC Cases On Legal ProfessionDocumento11 pagine10 SC Cases On Legal Professionrsurao24Nessuna valutazione finora

- WP10678 19 12 04 2019Documento10 pagineWP10678 19 12 04 2019ANIRUDH A KULKARNI 1650104Nessuna valutazione finora

- Utsav Kadam V State of AssamDocumento6 pagineUtsav Kadam V State of AssamAdvait ThiteNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemalatha Vs Tamil NaduDocumento8 pagineHemalatha Vs Tamil NaduJakkula LavanyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar CouncilDocumento19 pagineBar CouncilbabludassNessuna valutazione finora

- CasesDocumento14 pagineCasesofficialchannel8tNessuna valutazione finora

- Kalpesh P.C.surana Vs Indian Bank On 10 March, 2010Documento9 pagineKalpesh P.C.surana Vs Indian Bank On 10 March, 2010Ajay PathakNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court On False Litigation - Dalip Singh Vs State of UPDocumento7 pagineSupreme Court On False Litigation - Dalip Singh Vs State of UPvgopal_9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sarala JainDocumento5 pagineSarala JainArpit Goyal0% (1)

- Roshni Act RepealDocumento1 paginaRoshni Act RepealmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- RFPDocumento81 pagineRFPmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- CIRCULARDocumento8 pagineCIRCULARmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Latest JudgementDocumento17 pagineLatest JudgementmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract Award ArbitraryDocumento12 pagineContract Award ArbitrarymaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramana Dayaram Shetty Vs The International Airport ... On 4 May, 1979Documento36 pagineRamana Dayaram Shetty Vs The International Airport ... On 4 May, 1979Nikhila KatupalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramana Dayaram Shetty Vs The International Airport ... On 4 May, 1979Documento36 pagineRamana Dayaram Shetty Vs The International Airport ... On 4 May, 1979Nikhila KatupalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Is Time An Essence of ContractDocumento9 pagineIs Time An Essence of ContractVishakh NagNessuna valutazione finora

- Govt Order MPDocumento18 pagineGovt Order MPmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Very Important Debate On AllotmentDocumento23 pagineVery Important Debate On AllotmentmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Very Important Debate On AllotmentDocumento23 pagineVery Important Debate On AllotmentmaazmrdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Vitae (CV) : 1. Name: 2. Date of Birth: 3. EducationDocumento4 pagineCurriculum Vitae (CV) : 1. Name: 2. Date of Birth: 3. EducationSanjaya Bikram ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- NS5e RW4 ckpt1 U02-1Documento2 pagineNS5e RW4 ckpt1 U02-1hekmatNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan TemplateDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan Templateapi-318262033Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2 - PlanningDocumento52 pagineUnit 2 - PlanningBhargavReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Chance For European UniversitiesDocumento225 pagineA Chance For European UniversitiesFrancis CrickNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Step Goal-Setting Process-Brian TracyDocumento29 pagine12 Step Goal-Setting Process-Brian TracySanath Dasanayaka100% (7)

- A. Personal InformationDocumento5 pagineA. Personal InformationInas40% (5)

- Early Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftDocumento23 pagineEarly Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftInglês The Right WayNessuna valutazione finora

- The Relationships Among Work Stress Resourcefulness and Depression Level in Psychiatric Nurses 2015 Archives of Psychiatric NursingDocumento7 pagineThe Relationships Among Work Stress Resourcefulness and Depression Level in Psychiatric Nurses 2015 Archives of Psychiatric NursingmarcusnicholasNessuna valutazione finora

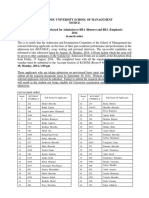

- Final List For BBA (Hons and Emphasis) KUSOM 2014Documento3 pagineFinal List For BBA (Hons and Emphasis) KUSOM 2014education.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation HRMDocumento9 paginePresentation HRMLi YuankunNessuna valutazione finora

- BP Cat Plan Risk AssesDocumento36 pagineBP Cat Plan Risk AssesErwinalex79100% (2)

- MCF Iyef Project ProposalDocumento9 pagineMCF Iyef Project ProposalKing JesusNessuna valutazione finora

- Casual Conversation RoleplayDocumento3 pagineCasual Conversation Roleplayapi-455177241Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan English 10Documento6 pagineLesson Plan English 10Butch RejusoNessuna valutazione finora

- Developmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistDocumento30 pagineDevelopmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistGene BonBonNessuna valutazione finora

- A Software Maintenance Methodology For Small Organizations - Agile - MANTEMA - Pino - 2011 - Journal of Software - Evolution and Process - Wiley Online Library PDFDocumento3 pagineA Software Maintenance Methodology For Small Organizations - Agile - MANTEMA - Pino - 2011 - Journal of Software - Evolution and Process - Wiley Online Library PDFkizzi55Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Beka Book - Basic SoundsDocumento4 pagineA Beka Book - Basic SoundsYurike Poyungi100% (1)

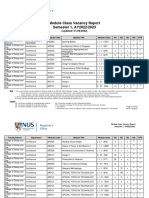

- VacancyRpt R3 2223S1Documento273 pagineVacancyRpt R3 2223S1Lim ShawnNessuna valutazione finora

- Newspaper 1Documento2 pagineNewspaper 1api-321772895Nessuna valutazione finora

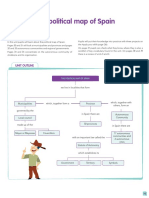

- The Political Map of Spain: Unit OutlineDocumento6 pagineThe Political Map of Spain: Unit OutlineIsabel M Moya SeguraNessuna valutazione finora

- Latvia Home Economics Philosophy-Ies 2012 PowerpointDocumento31 pagineLatvia Home Economics Philosophy-Ies 2012 PowerpointJobelle Francisco OcanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rachel Dow March 2019Documento1 paginaRachel Dow March 2019api-414910309Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDocumento27 pagineGender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (2)

- Unit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade TeachingDocumento3 pagineUnit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade Teachingapi-550734106Nessuna valutazione finora

- FR CDS I 22 OTA Engl 120123 PDFDocumento6 pagineFR CDS I 22 OTA Engl 120123 PDFSatyam MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Schools in MumbaiDocumento12 pagineSchools in Mumbaivj_174Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper 1Documento20 pagineResearch Paper 1api-269479291100% (2)

- 0580 s14 QP 23Documento12 pagine0580 s14 QP 23HarieAgungBastianNessuna valutazione finora

- Man 3025 - CHPT 1. STUDocumento27 pagineMan 3025 - CHPT 1. STUIleana ColettaNessuna valutazione finora