Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Allen 1988

Caricato da

José BlancasCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Allen 1988

Caricato da

José BlancasCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Biocultural Restoration of a Tropical Forest

Author(s): William H. Allen

Source: BioScience, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Mar., 1988), pp. 156-161

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Institute of Biological Sciences

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1310447 .

Accessed: 28/09/2013 21:38

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press and American Institute of Biological Sciences are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to BioScience.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Bioculturalrestoration of a tropical forest

Architects of Costa Rica's emerging GuanacasteNational Park

plan to make it an integralpart of local culture

ne hot, windy day last sum- Biocultural restoration: "user-friendly" social institution that

mer, Daniel Janzenleaned in contributes to daily life, just as do

through the window of an

philosophy libraries,hospitals, and schools.

open-airschoolhousein northwestern Although the Guanacaste project may In addition to the intellectual di-

Costa Rica and called to the teacher. be the single most significant ecologi- mension of biocultural restoration,

The teacher left the blackboard, cal restoration effort in the neotro- the parkwill offerother, morepracti-

where he had been working a math pics, its emphasis on biocultural res- cal assets. The park, for example,

problem. After chatting with the toration is also noteworthy. Rather encompasses a watershed that pro-

teacherfor a few minutesin Spanish, than planting trees, the thrust of bio- vides drinking and irrigation water

Janzen handed him a photocopied cultural restoration is to embed bio- and contains genetic stocks valuable

note inviting the elementary school logical understanding in the local cul- to Costa Rica's future. The Guana-

studentsto attend a speech by Costa ture by encouraging interaction caste area will benefit from money

Rican PresidentOscar Arias Sanchez between the park and nearly 40,000 acquired as a result of the park's

in which Ariaswas to reaffirmconser- neighbors. The potential rewards for education,research,and tourismpro-

vation as one of the nation's top local residents in particular and Costa grams. For instance, the region cur-

priorities.The speechwould be given Rica in general are economic and rentlyabsorbssome $200,000 a year,

at nearbySanta Rosa National Park, environmental, but most importantly thanksto researchprojectswhose re-

where the class had already studied they are intellectual, Janzen argues. quirements range from supplies to

naturalhistory as part of a new edu- During 25 years of ecological re- field assistants. Janzen predicts the

cationalprogram.The invitationwas search in Costa Rica, Janzen has ob- figurewill top $1 million as the park

deliveredto severalother elementary served the development of the Guana- evolves and attractsmore scientists.

schools in the region, as well as to caste region from a "frontier society However, materialgoods and uses

farmers,politicians, and other local to a thoroughly agriculturalized one." should not be assignedtoo much sig-

residents. He has hired residents as field assis- nificance, says Janzen. "This is not

For Janzen, a biologist at the Uni- tants, given lectures to local groups, the basis on which a park should be

versity of Pennsylvaniain Philadel- and chatted with Costa Ricans from established,"he says. "If it is, you're

phia, this errand was another small all walks of life. Although upward always going to lose it becausesome-

part of a plan to save and maintaina mobility in Guanacaste is limited and body is going to come along someday,

large tropical forest-not a rain for- formal schooling minimal, the entire probably five to ten years from now,

est, but a dry forest. Janzen is the population is literate and displays with an economic use that is better

majorforce behindan ambitiousproj- great curiosity, he says. "The public is than whatever the use is you come up

ect to establishGuanacasteNational starving for and responds immediate- with."

Park,a 75,000-hectarereservenamed ly to presentations of complexity of "If Guanacaste National Park is to

afterits host provinceand the nation- all kinds-biology, music, literature, survive into perpetuity, it must be

al tree.UsingSantaRosa as a nucleus, politics, education, et cetera." In viewed with unanimous favor by a

the parkis beingpiecedtogetherfrom Guanacaste, Janzen sees an opportu- diverse array of political, economic,

deforested land and existing forest nity to feed hungry intellects and and cultural factions," Janzen says.

(See box, p. 158). With a mix of simultaneously save a forest. "In my experience, people do not

traditionaland innovative ecological "The goal of biocultural restora- wish to destroy complexity that

restoration techniques, the project tion is to give back to people the doesn't threaten them, and in fact

aims to return the land to its pre- understanding of the natural history they very aggressively seek it out."

conquistadorstate, with securenum- around them that their grandparents

bers of the area's original flora and had," Janzen says. "These people are Biocultural restoration:

fauna. now just as culturally deprived as if

they could no longer read, hear mu-

methodology

sic, or see color." Thus the park must The essence of biocultural restoration

by William H. Allen be developed into what Janzen calls a is to make the park into a "living

156 BioScience Vol. 38 No. 3

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A view of Santa Rosa National Park,which would be the nucleusof the proposedGuanacasteNational Park.The park is being

piecedtogetherfrom deforestedland and existing forest fragments.Photos:WilliamH. Allen.

I

classroom"-through programs for teaching effort. "The teaching pro- systemalso will be a rich resourcefor

gradeschool, high school, and univer- gram is intended to be as much a part other Costa Ricans as well as foreign

sity students;civic groups; and tour- of the park as is an entrance road, tourists.

ists from Costa Rica and elsewhere. beach, visitor center, or block of vir- Already,teachershave become fo-

The park'splan also calls for encour- gin forest," Janzen says. cal points for local activities other

aging independentexplorationof the Until the teaching program started, than biological education.For exam-

park, awarding trips to other pre- Santa Rosa received irregular visits ple, one teacher, Giovanni Bassey, a

serves, and assigninglay apprentices from local school and university marinebiologist based at Cuajiniquil

to teachers,researchers,and officials groups and from graduate students (a coastal fishingvillageon the north-

workingin the park. taking courses through the Organiza- ern boundary of the park), fills the

Guanacasteis to become an inte- tion for Tropical Studies in San Jose, roles of biology teacher, scientific

gral arm of the traditional school Costa Rica, as well as various US consultant,park public relationsoffi-

systemby teachingecology and natu- universities. Now, two Costa Rican cial, and civic leader.Within a month

ral history in the park itself, with biologists run the program full time, of beginninghis job last September,

professionalCosta Ricanbiologistsas and up to five may be needed when Bassey was invited to chair the vil-

teachers.The formal education pro- the program reaches maturity. Plans lage's civic committeeand was asked

gram,begunin March 1987 and sup- call for several thousand grade and by several villagers about the best

portedby grantsfromtheJessieSmith high school students in the region to places to build houses and set nets.

Noyes Foundationin New YorkCity visit the park for a full day of field "IntheoryGiovanniis doing the same

and the C. S. Fundin Freestone,Cali- biology at least once a year. Research thing our teacher inside the park is

fornia,drawsupon knowledgegained scientists in the park get involved in doing-just teaching basic biology,"

during more than two decades of the program by making guest appear- says Janzen. "But he's also a major

research in the region, as well as ances in the classroom or by leading contact point between the park and

tropicalbiologicalresearchpublished field trips. A program for adult mem- the fishermen."

aroundthe world. Findingsfrom the bers of the local community is The teachers,who have solid oral

park's ongoing research programs planned. Although oriented toward communicationskills in additionto a

will be incorporateddirectlyinto the local residents, the park's educational stronggraspof biology, usuallyspend

March 1988 157

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ecological restoration

The Guanacaste National Park project in northwestern Costa Rica is an

eleventh-hour effort to save one of tropical America's last dry forests.

The aim of the $11.8-million project is to take existing dry forest return to the central point and sepa-

fragments in Guanacaste Province and restore to intact condition ap- rate the items into species. Afterwards

proximately 75,000 hectares of topographically diverse land, which will the class discusses what a species is

support the animal and plant species that predated the arrival of the and why fruits and seeds vary in

Spaniards in the 16th century. The habitat is primarily dry forest, shape, size, color, and other traits.

although a significant portion of the area is a rain forest refugium for "When we go into the field, I try to

animals in the dry season. Bisected by the Pan-American Highway, the ask them questions to make them

proposed park area has beaches, islands, two volcanos, serpentine ridges, think, instead of just telling them

volcanic mesas, seasonal watercourses, and ever-flowing rivers. about what they're seeing," says Liz

Ecological restoration of the park is already under way. Trees are being Brenes, the teacher based at Santa

planted, and fire-control efforts, including establishment of fire lanes, Rosa. "I want to help them under-

have begun. Hunting is prohibited because it threatens seed-dispersing stand the importance of a national

animals. A moderate amount of livestock grazing is planned to control park and why they have to take care

jaragua, a dense African grass that blocks the growth of young trees, of natural resources."

fuels fires, and provides cover for rodents that consume tree seeds. Following lunch, the group is led

Scientists expect a closed canopy throughout much of the park in two to on a two-hour tour of different forest

five decades. Within 100 years, the park should be largely free of grass, types, discussing the plants, animals,

and, in 300 years, it is expected to be an intact forest. and patterns they encounter. The day

Fundraising, land purchases, and organization of the park's manage- ends with another lecture in a com-

ment structure have progressed steadily since the project was publicly fortable part of the forest or at the

announced in February 1986 at the National Zoological park in Wash- park's teaching center. By 4:00 P.M.,

ington, DC (BioScience 37:83). Land purchases are made by the Funda- the class is on its way home. Some

ci6n Neotr6pica, a Costa Rican conservation organization that works school groups are chosen for repeat

closely with government agencies and political officials to obtain the sessions based on their talent and

lowest possible price. All land bought for the park automatically enthusiasm.

becomes property of the Fundacion, which will transfer it to the Servicio The program aims to inspire biolo-

de Parques Nacionales, the Costa Rican park service, when acquisition is gy-related activities at the schools

complete. themselves, as well as deeper interac-

By mid-1987, about half of the proposed park had been declared tion with tropical nature by students,

national park and half was in "zona protectora" status, a legal condition teachers, and parents. The forest res-

in which logging and other destructive activities are banned. Of the total toration and inventory projects draw

75,000 hectares, 46% was owned by the project and a down payment these and other citizens into the park

had been put on another 19%. Completion of the purchase depends on by offering them nonpaying, research

further fundraising. technician apprenticeships. These

projects involve locating seed crops;

collecting, cleaning and planting

two days a week absorbinginforma- park at 7:30 A.M. "They take a short, seeds; recording seedling fates; and

tion about the biology of the area. one-hour walk through a patch of inventorying insects and plants. Ap-

They read, engagein long discussions forest on a winding trail, stopping prenticeships to park personnel,

with researchers,and activelypartici-frequently to look closely at orga- which would involve caring for hors-

pate in other courses given in the nisms and patterns," Janzen says. The es, clearing trails, managing the en-

park, such as the three-week,gradu- teacher tells them straightforward trance kiosk, and cutting and burning

ate-level field ecology course Janzenstories about the natural history of fire lanes, could lead to apprentice

teaches each March. They generally some of the very conspicuous trees, and professional positions as natural-

spend three days a week teaching insects, birds, and mammals, as op- ist guides for tourists.

schoolchildrenwho come to the park, portunity strikes." As the educational program

transportedeither by local police or Arriving at a central location, the evolves, it will expand to include two-

by arearesidents.The projectplans to group listens to a short lecture about day or longer field classes with more

purchasea microbusearly in 1988 to the biology of a particular group of complex teaching projects, during

transportstudents. organisms chosen as the focus for the which the students will remain in the

morning. For example, in April, the park. Some field classes will move out

topic might be the fruits and seeds of the Santa Rosa nucleus to explore

Teaching and exploring maturing on the forest floor. After the regions around three recently com-

A typicalday for a Guanacasteteach- lecture, the students are sent out for a pleted biological research stations on

er begins when a class of about 16 half-hour to gather as many kinds of and around Volcan Cacao and Volcan

grade school students arrives at the fruits and seeds as they can find. They Orosi in the park's eastern section.

158 BioScience Vol. 38 No. 3

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Displaysand museumexhibitswill be

created at various locations in the

park.A regionallibrarywill be devel-

oped in Liberia,the provincial capi-

tal. Parkpersonnelwill encouragethe

growth of natural history clubs, in-

cluding bird-watchingand butterfly-

collectinggroups.

Increasing Guanacaste's

prospects for survival

Althoughthe primaryaim of the edu-

cational program is to expose the

local population to natural history

and thus enhance biological under-

standing,it also is crucialto the sur-

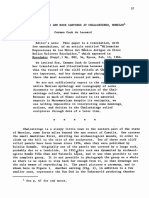

vival of Guanacaste National Park. Daniel Janzen (left) talks with Costa Rican PresidentOscar Arias Sanchez (center)

"The most practicaloutcome is that duringa visit by Ariasto SantaRosa National Parkon 25 July 1987. In a speech,Arias

this programwill beginto generatean affirmedconservationas one of the nation's top priorities.He signed proclamations

ongoing populace that understands annexingpartof the SantaElenaPeninsulato SantaRosa and grantingzona protectora

biology," Janzen says. "In 20 to 40 status to anothermajorportion of land sought for GuanacasteNational Park.

years, these childrenwill be running

the park, the neighboringtowns, the m l Ia

irrigation systems, the political sys- managerscreatea detailedzoning sy- accessibility. The Pan-American

tems. When someone comes along tem, developed with the park's bio- Highwayis an ideal startingpoint for

with a decision to be made about logical peculiaritiesin mind. In addi- this road system, which, properly

conservation,resource management, tion, a good system of trails and constructed and maintained, should

or anythingelse, you want that per- seasonal and all-weatherroads must not be a major barrier to animal

son to understandthe biologicalpro- be establishedto enhance the park's movement.

cesses that are behind that decision

becausehe or she knew about them

[since]grade school."

Touristsalso will benefit from the

park'seducationprogram.Janzenex-

pects Guanacasteto become a major

touristattractionbecauseof its beau-

ty and its intellectual offerings. For

the parkto becomemorethan a quick

stopoveron the tourist route, howev-

er, living facilities and other tourist

services must be developed. He has

appealedto privateindividualsin the

area to accomplishthis task. Mean-

while, Janzen also is pushing for "a

smallamountof dry forestaffirmative

I

action" so the naturalhistory tourist ' ' _F:-'

'

" " * -"

'.^' ? ' ''

world does not think of Costa Rica ,"'* j i ,! L '. 4ji A ', 1

solely as a rain forest mecca.

If the park is to be used heavily by v

-0: j ?. .:-'. . ' .. . '

tourists,scientists,educators,and stu- gFVt;

.. . . '?-

t~~~,f@e '-:kr*.-

..*'a'.. .*l,

dents,these groups,which often have ? : ~ ? ,. ~. ,.: ? . .., .~ .~,~:~~.:~<~:~;:~ ,. .

",

' ~ . ....

conflicting interests, must be kept

from trippingover one another,even

within a park as large as Guanacaste. buildingatop VolcanCacaoon

The newlyconstructeddormitory-laboratory-classroom

Thus,Janzenhas proposed that park land purchasedfor the proposedpark.

March 1988 159

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I

Janzen calls "biotic challenges"-in-

cluding snakes, ticks, disease, thirst,

andwounds. Not only is hiringGuan-

acaste residentsa logical use of local

know-how, it also is establishingdi-

rect as well as subtle links between

the park and the province'seconomic

and social structures. This strategy

will bond the local communitymore

tightlyto the parkthan if parkservice

employees were brought in from

elsewhere.

About 50 area residentsare needed

for the early stages of park restora-

tion, some to perform management

tasks and others to do basic mainte-

nance. These workers will live pri-

Horsesgrazingin SantaRosa National Park.Along with cows and otheranimals,they

are expectedto play an importantrole in dispersingtree seeds throughoutGuanacaste marilyon parkhomesteads,theirchil-

National Park. drenwill go to local schools, and the

families will have access to the nor-

mal social life of the region. Those

who excel are expected to rise

Local management ment. Although many residents will through the ranks of the park's ad-

need trainingin biology and commu- ministrativestructure,and some may

Just as the education program con- nicationskills,they alreadyare skilled move into research and teaching

tributesto bioculturalrestorationby at suchtechnicalaspectsof parkman- programs.

offeringthe parkto the people, Guan- agementas fightingfires,constructing As of December1987, a total of six

acaste'smanagementplan contributes fences, caringfor horses, maintaining managers of local haciendas pur-

by applying the knowledge, energy, trails and buildings, herding cattle, chased to become part of the park

and spiritof the local people to long- identifyingand understandingplants had been hiredas park site managers.

term and day-to-day park manage- and animals, and dealing with what At Cerroel Hacha, purchasedin Jan-

uary 1987 (see box, p. 161), two

farmerswere hiredas managers.They

were allowed to stay in their houses

and cultivatea small portion of their

fields as a salary supplement. They

enlargedtheir houses into biological

stations, mapped vegetation on the

farms, and received training from a

local game warden on handling

poachersand public relations.

One of the ownersof a 200-hectare

parcelon VolcanCacaothat was pur-

chased for the park was hired to

continueliving in his remotehouse to

serve as a deputy to the warden.

PedroJose Mejia has since enlarged

his house and built an adjacentdor-

mitory-laboratory-classroom com-

plex with a majesticwestwardview of

the park and PacificOcean. Like the

residentmanagersat Cerroel Hacha,

Mejia provides food and shelter to

scientistswho use the biological sta-

DanielJanzenpinningmoths in the cabinwherehe lives six monthsof the yearin Santa tion as a base for researchand teach-

Rosa National Park. ing. The site also served as the loca-

160 BioScienceVol. 38 No. 3

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1 The sociology of a land purchase

Even on the face of it, the deal Daniel Janzen arranged with 14 farm

families who owned land in the Cerro el Hacha area of the proposed

tion for a three-day management Guanacaste National Park was complicated. But it took more than an

policy conference attended by 25 ability to bargain over real estate to keep everyone smiling.

Costa Rican forest reserve managers The pieces of the deal had come together over a year. First, Janzen

last fall. convinced the farmers to stop clearing forest until their property could be

bought for the park. Next, the project received a large grant from John

D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. More negotiations with the

Resisting formulas farmers followed, this time about price and date of the sale.

The formula for ecologically and bio- But a subtle and dangerous issue remained. The farmers insisted on

culturally restoring and maintaining receiving cash for their land. Janzen insisted that the transaction be

the forest that will become Guana- conducted within the walls of a bank in the nearby town of La Cruz and

caste National Park is home grown. It that the farmers immediately deposit their proceeds in a savings account.

was devised to match the particular He made this demand to protect the farmers from robbery and to protect

biological, political, economic, and himself and the park project from bad public relations.

social circumstances of northwestern "This is a patronistic society where a person in my position is expected

Costa Rica today rather than to fulfill to have a sense of responsibility about the farmer," Janzen says, noting

some accepted model for national that a farmer who was robbed would soon be asking for the farm back

parks. and the park would be expected to help him. "A robbery would have

The plan for the park evolved in a been viewed as partly my fault, and, furthermore, we would have had a

practical and pragmatic way. During very upset person. Now the upset person might not have blamed me

his years in Guanacaste Province, Jan- personally, but he would nevertheless be very upset, which would then

zen observed many "challenges" to mean that the community would see me as generating upset people."

the biology of the tropical forest- The farmers acceded to Janzen's demand. He made arrangements with

fire, hunting, logging, ranching, and the bank manager to open savings accounts on the spot and to keep the

farming. His reaction was to look for bank open as long as necessary for the transactions.

strategies to counter those particular On 23 January 1987, a special table was set up on one side of the bank

challenges. lobby. Various legal documents and several suitcases full of one-thou-

"You don't have to go to some sand-colone bills covered it. Behind the table sat officials from Fundaci6n

international committee to get man- Neotr6pica, the Costa Rican conservation organization that coordinates

agement started," he says. "It's all land purchases for the park. Janzen, the chief engineer of the event, stood

been practical here. The statement in the background "taking pictures," as he says.

that a local farmer is the best person The farmers filed in, counted out their colones, carried armfuls across

to deal with fires and tree planting the lobby to the teller windows, opened accounts, and deposited their

can be converted to an ideal. You can money-sums of as much as a million colones (about $16,000). The

result: more land for the park, no robberies, and a lot of happy farmers.

say, well, this is marvelous; this in-

volves local people. But you can also "They all walked out of there with passbooks in their hands, and I know

be very practical and say that local that at least six of them still have those accounts," Janzen says.

people are probably the best people

there are to do this."

When pressed, Janzen acknowl- world. But this would be as erroneous you have rather than reading some-

as if Guanacaste had been modeled one else's book." D

edges that some may use the Guana-

caste National Park formula as a after Yosemite National Park in Cali-

model for establishing tropical na- fornia, he says. "You've got to sit WilliamH. Allen is a sciencewriterbased

tional parks in other parts of the down and look at the circumstance in Urbana,Illinois.

161

March 1988

This content downloaded from 128.220.8.15 on Sat, 28 Sep 2013 21:38:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Uncertain Path: A Search for the Future of National ParksDa EverandUncertain Path: A Search for the Future of National ParksValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- Guanacaste National ParkDocumento105 pagineGuanacaste National ParkLuisNessuna valutazione finora

- Mar-Apr 2008.Qxp:Jul 97 IssueDocumento8 pagineMar-Apr 2008.Qxp:Jul 97 Issueapi-20792794Nessuna valutazione finora

- Science Must Embrace Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge To Solve Our Biodiversity CrisisDocumento4 pagineScience Must Embrace Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge To Solve Our Biodiversity CrisisirisavalonNessuna valutazione finora

- Menzies CR 2003 Traditional Ecological Knowledge and NAtural Resource Management University of Nebraska Press PDFDocumento281 pagineMenzies CR 2003 Traditional Ecological Knowledge and NAtural Resource Management University of Nebraska Press PDFMara X Haro LunaNessuna valutazione finora

- Oceans Kansas School Field Trips Truly Go To The Field !Documento6 pagineOceans Kansas School Field Trips Truly Go To The Field !JayhawkNessuna valutazione finora

- Geoparks and Geostories Ideas of Nature Underlying The Unesco Araripe Basin Project and Contemporary Folk NarrativesDocumento25 pagineGeoparks and Geostories Ideas of Nature Underlying The Unesco Araripe Basin Project and Contemporary Folk NarrativesHori HoriNessuna valutazione finora

- Aug-Oct 2010 Bexar Tracks Bexar Audubon SocietyDocumento10 pagineAug-Oct 2010 Bexar Tracks Bexar Audubon SocietyBexar Audubon SocietyNessuna valutazione finora

- David Muench's National Parks: Native Ceremony and Myth on the Northwest CoastDa EverandDavid Muench's National Parks: Native Ceremony and Myth on the Northwest CoastNessuna valutazione finora

- Jarwa UnescoDocumento220 pagineJarwa UnescoNeha VijayNessuna valutazione finora

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Natural Resource ManagementDocumento281 pagineTraditional Ecological Knowledge and Natural Resource ManagementShannon FergusonNessuna valutazione finora

- Andaman Island PDFDocumento220 pagineAndaman Island PDFAlexandra Roxana100% (1)

- Symposium WebsiteDocumento2 pagineSymposium WebsiteMisterJanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sfu Library Thesis DeadlineDocumento12 pagineSfu Library Thesis Deadlineafkolhpbr100% (2)

- The Smell of Marsh Mud: Matagorda Island National Wildlife RefugeDocumento3 pagineThe Smell of Marsh Mud: Matagorda Island National Wildlife RefugeRYIESENessuna valutazione finora

- Get The Principles of Nature ConservationDocumento6 pagineGet The Principles of Nature ConservationBanjar Yulianto LabanNessuna valutazione finora

- COsmologia ArticuloDocumento13 pagineCOsmologia ArticuloMaria Sirex Consuegra Díaz-GranadosNessuna valutazione finora

- Elaine P. Dela Cruz - Restorative Mangrove Reforestation and Eco Tourism Project Sustaining Excellence in Governance of Extension Delivery PracticesDocumento5 pagineElaine P. Dela Cruz - Restorative Mangrove Reforestation and Eco Tourism Project Sustaining Excellence in Governance of Extension Delivery Practicesneboydc100% (1)

- Drafting a Conservation Blueprint: A Practitioner's Guide To Planning For BiodiversityDa EverandDrafting a Conservation Blueprint: A Practitioner's Guide To Planning For BiodiversityNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review On National ParksDocumento4 pagineLiterature Review On National Parksfvhacvjd100% (1)

- Large Mammal Restoration: Ecological And Sociological Challenges In The 21St CenturyDa EverandLarge Mammal Restoration: Ecological And Sociological Challenges In The 21St CenturyNessuna valutazione finora

- Suisun Marsh: Ecological History and Possible FuturesDa EverandSuisun Marsh: Ecological History and Possible FuturesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Local Knowledge of Dayaknese: Case Study of Pahewan TabaleanDocumento5 pagineThe Local Knowledge of Dayaknese: Case Study of Pahewan TabaleanNhư AnnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wildlife ConservationDocumento104 pagineWildlife Conservationmegan-krekorian-7417100% (1)

- FINAL-Dizon Group-3 Chapters-1 5 TPPDDocumento76 pagineFINAL-Dizon Group-3 Chapters-1 5 TPPDFiona Mortega100% (1)

- HORTA, Regina - Zoos in Latin AmericaDocumento21 pagineHORTA, Regina - Zoos in Latin AmericaAnonymous OeCloZYzNessuna valutazione finora

- The Fragmented Forest: Island Biogeography Theory and the Preservation of Biotic DiversityDa EverandThe Fragmented Forest: Island Biogeography Theory and the Preservation of Biotic DiversityNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashkui ChapterDocumento20 pagineAshkui ChapterGerardo TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- The Knowledge of Nature and the Nature of Knowledge in Early Modern JapanDa EverandThe Knowledge of Nature and the Nature of Knowledge in Early Modern JapanValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Ecotourism 2Documento11 pagineEcotourism 2sumber uripNessuna valutazione finora

- Wild Profusion: Biodiversity Conservation in an Indonesian ArchipelagoDa EverandWild Profusion: Biodiversity Conservation in an Indonesian ArchipelagoValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Dolmatoff. Cosmology As Ecological AnalysisDocumento13 pagineDolmatoff. Cosmology As Ecological AnalysisJuan Camilo Hernández RodríguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Ocean-Aquariums and Their Visitor Experiences: An Instrument For Promoting Tourism and Aquatic Wildlife ConservationDocumento8 pagineOcean-Aquariums and Their Visitor Experiences: An Instrument For Promoting Tourism and Aquatic Wildlife ConservationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- PuertoPrincesa eDocumento4 paginePuertoPrincesa eMaribel Bonite PeneyraNessuna valutazione finora

- Native American PerspectiveDocumento10 pagineNative American PerspectiveKaisha MedinaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Once and Future Forest: A Guide To Forest Restoration StrategiesDa EverandThe Once and Future Forest: A Guide To Forest Restoration StrategiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecological Integrity Evaluating Success PDFDocumento6 pagineEcological Integrity Evaluating Success PDFVva KrdnNessuna valutazione finora

- University of Nebraska Press The Settler SeaDocumento11 pagineUniversity of Nebraska Press The Settler SeaCalibán CatrileoNessuna valutazione finora

- Higgs (2005)Documento6 pagineHiggs (2005)Rodrigo Alejandro Ruiz RiquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Horticulture 01 02 2024 011Documento1 paginaHorticulture 01 02 2024 011dosono4727Nessuna valutazione finora

- Botanical GardensDocumento6 pagineBotanical GardensbuffysangoNessuna valutazione finora

- Reichel-Dolmatoff Cosmology As Ecological PerspectiveDocumento13 pagineReichel-Dolmatoff Cosmology As Ecological PerspectiveEric WhiteNessuna valutazione finora

- July-August 2005 Sego Lily Newsletter, Utah Native Plant SocietyDocumento10 pagineJuly-August 2005 Sego Lily Newsletter, Utah Native Plant SocietyFriends of Utah Native Plant SocietyNessuna valutazione finora

- At the Feet of Living Things: Twenty-Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in IndiaDa EverandAt the Feet of Living Things: Twenty-Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in IndiaAparajita DattaNessuna valutazione finora

- Flora and Fauna ThesisDocumento6 pagineFlora and Fauna Thesisuxgzruwff100% (2)

- Roots of Food and MedicineDocumento2 pagineRoots of Food and MedicineAnonymous OXeVkENessuna valutazione finora

- Salmon and Acorns Feed Our People: Colonialism, Nature, and Social ActionDa EverandSalmon and Acorns Feed Our People: Colonialism, Nature, and Social ActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Connection of Indigenous Knowledge To Science and TechnologyDocumento4 pagineConnection of Indigenous Knowledge To Science and TechnologyMark Vincent Z. Padilla100% (3)

- The Volunteer: Playing Defense Along The Lavender Trail Volunteer OpportunitiesDocumento6 pagineThe Volunteer: Playing Defense Along The Lavender Trail Volunteer OpportunitiesAEHillNessuna valutazione finora

- The Return of the Unicorns: The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned RhinocerosDa EverandThe Return of the Unicorns: The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned RhinocerosNessuna valutazione finora

- Roof To RainforestDocumento8 pagineRoof To RainforestSachinNessuna valutazione finora

- National Park ReportDocumento7 pagineNational Park Reportapi-356217402Nessuna valutazione finora

- Discovering The Chesapeake, The History of An EcosystemDocumento414 pagineDiscovering The Chesapeake, The History of An EcosystemThejaNessuna valutazione finora

- Where the Gods Reign: Plants and Peoples of the Colombian AmazonDa EverandWhere the Gods Reign: Plants and Peoples of the Colombian AmazonValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (5)

- Last Child in The Woods: AcornDocumento12 pagineLast Child in The Woods: AcornSalt Spring Island ConservancyNessuna valutazione finora

- Econ Bot 2015 DasDocumento15 pagineEcon Bot 2015 DasJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Econ Bot 2015 PoolDocumento15 pagineEcon Bot 2015 PoolJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Forests Trees and Livelihoods 2015 Kanmegne-1Documento11 pagineForests Trees and Livelihoods 2015 Kanmegne-1José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- 1996 LeakeyDocumento309 pagine1996 LeakeyJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Wood and Non-Wood Forest Products of Central Java, IndonesiaDocumento19 pagineWood and Non-Wood Forest Products of Central Java, IndonesiaJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- American Schools of Oriental Research: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocumento7 pagineAmerican Schools of Oriental Research: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Abdelgadir 2013Documento15 pagineAbdelgadir 2013José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Agriculture 08 00141Documento20 pagineAgriculture 08 00141José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Tansley ReviewDocumento20 pagineTansley ReviewJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives To Sustainable Development and The Green EconomyDocumento14 pagineBuen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives To Sustainable Development and The Green EconomyJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Sanou 2015Documento11 pagineSanou 2015José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Keh Len Beck 2004Documento10 pagineKeh Len Beck 2004José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecological Society of AmericaDocumento7 pagineEcological Society of AmericaJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- AICA Vol14 Trabajo010Documento6 pagineAICA Vol14 Trabajo010José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Luna Vega2013Documento21 pagineLuna Vega2013José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- JETHNO D 21 01041 ReviewerDocumento39 pagineJETHNO D 21 01041 ReviewerJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Forests 11 00991 v2Documento24 pagineForests 11 00991 v2José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Sweet Man 2017Documento15 pagineSweet Man 2017José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- What Happens To Traditional Knowledge and Use of Natural Resources When People MigrateDocumento33 pagineWhat Happens To Traditional Knowledge and Use of Natural Resources When People MigrateEmel Marissa OrhunNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 1016@j Chroma 2005 07 058Documento18 pagine10 1016@j Chroma 2005 07 058José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- 48 59Documento13 pagine48 59José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- HFS Module3 Unit1Documento56 pagineHFS Module3 Unit1José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- CAPITULODELIBROBurseraceae Kubitzki ONLY1Documento38 pagineCAPITULODELIBROBurseraceae Kubitzki ONLY1José BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Use of Indigenous KnowledgeDocumento30 pagineThe Use of Indigenous KnowledgeJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- 1965 CallenDocumento9 pagine1965 CallenJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- A X0098e PDFDocumento130 pagineA X0098e PDFJosé Blancas100% (1)

- Editor's: ProvideDocumento28 pagineEditor's: ProvideJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity in Forest Management: Non - Timber Forest Products and BushDocumento10 pagineDiversity in Forest Management: Non - Timber Forest Products and BushJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Voucher Specimens in Ethnobiological Studies and PublicationsDocumento8 pagineVoucher Specimens in Ethnobiological Studies and PublicationsJosé BlancasNessuna valutazione finora

- SCIENCE 11 WEEK 6c - Endogenic ProcessDocumento57 pagineSCIENCE 11 WEEK 6c - Endogenic ProcessChristine CayosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Docket - CDB Batu GajahDocumento1 paginaDocket - CDB Batu Gajahfatin rabiatul adawiyahNessuna valutazione finora

- 3) Uses and Gratification: 1) The Hypodermic Needle ModelDocumento5 pagine3) Uses and Gratification: 1) The Hypodermic Needle ModelMarikaMcCambridgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ultimate Trading Guide - Flash FUT 2023Documento33 pagineUltimate Trading Guide - Flash FUT 2023marciwnw INessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 19 Code Standards and ReviewDocumento27 pagineLecture 19 Code Standards and ReviewAdhil Ashik vNessuna valutazione finora

- Extraction of Mangiferin From Mangifera Indica L. LeavesDocumento7 pagineExtraction of Mangiferin From Mangifera Indica L. LeavesDaniel BartoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Answer: C: Exam Name: Exam Type: Exam Code: Total QuestionsDocumento26 pagineAnswer: C: Exam Name: Exam Type: Exam Code: Total QuestionsMohammed S.GoudaNessuna valutazione finora

- Institutions and StrategyDocumento28 pagineInstitutions and StrategyFatin Fatin Atiqah100% (1)

- Population Second TermDocumento2 paginePopulation Second Termlubna imranNessuna valutazione finora

- Agrinome For Breeding - Glossary List For Mutual Understandings v0.3 - 040319Documento7 pagineAgrinome For Breeding - Glossary List For Mutual Understandings v0.3 - 040319mustakim mohamadNessuna valutazione finora

- This Is A Short Presentation To Explain The Character of Uncle Sam, Made by Ivo BogoevskiDocumento7 pagineThis Is A Short Presentation To Explain The Character of Uncle Sam, Made by Ivo BogoevskiIvo BogoevskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Emerging Technology SyllabusDocumento6 pagineEmerging Technology Syllabussw dr100% (4)

- FINAL VERSION On Assessment Tool For CDCs LCs Sept. 23 2015Documento45 pagineFINAL VERSION On Assessment Tool For CDCs LCs Sept. 23 2015Edmar Cielo SarmientoNessuna valutazione finora

- Level of Organisation of Protein StructureDocumento18 pagineLevel of Organisation of Protein Structureyinghui94Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bichelle HarrisonDocumento2 pagineBichelle HarrisonShahbaz KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management: Frank K. Reilly & Keith C. BrownDocumento113 pagineInvestment Analysis and Portfolio Management: Frank K. Reilly & Keith C. BrownWhy you want to knowNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Communication at Mahabharatha WarDocumento19 pagineRole of Communication at Mahabharatha WarAmit Kalita50% (2)

- Peanut AllergyDocumento4 paginePeanut AllergyLNICCOLAIONessuna valutazione finora

- Land CrabDocumento8 pagineLand CrabGisela Tuk'uchNessuna valutazione finora

- Art Appreciation Chapter 3 SummaryDocumento6 pagineArt Appreciation Chapter 3 SummaryDiego A. Odchimar IIINessuna valutazione finora

- 16 - Ocean Currents & Salinity Interactive NotebookDocumento23 pagine16 - Ocean Currents & Salinity Interactive NotebookRaven BraymanNessuna valutazione finora

- Leather PuppetryDocumento8 pagineLeather PuppetryAnushree BhattacharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment - 1 AcousticsDocumento14 pagineAssignment - 1 AcousticsSyeda SumayyaNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 - TechDocs, Acft Gen, ATAs-05to12,20 - E190 - 202pgDocumento202 pagine01 - TechDocs, Acft Gen, ATAs-05to12,20 - E190 - 202pgေအာင္ ရွင္း သန္ ့Nessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction Spreadable Media TtsDocumento22 pagineIntroduction Spreadable Media TtsYanro FerrerNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Students' Error in Using Possesive Adjective in Their Online Writing TasksDocumento19 pagineAn Analysis of Students' Error in Using Possesive Adjective in Their Online Writing TasksKartika Dwi NurandaniNessuna valutazione finora

- ManualDocumento50 pagineManualspacejung50% (2)

- Affidavit of Co OwnershipDocumento2 pagineAffidavit of Co OwnershipEmer MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan For DemoDocumento9 pagineLesson Plan For DemoJulius LabadisosNessuna valutazione finora

- Aircraft Wiring Degradation StudyDocumento275 pagineAircraft Wiring Degradation Study320338Nessuna valutazione finora