Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

157 162 PDF

Caricato da

Xena MarianaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

157 162 PDF

Caricato da

Xena MarianaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

SCHOOLBASED PROGRAMS TO PREVENT AND grades 8 and 9). At that point, more than 50 percent of ado

REDUCE ALCOHOL USE AMONG YOUTH lescents report ever having consumed alcohol in their life

time (Kosterman et al. 2000). Given this natural history of

alcohol use in adolescence, most schoolbased programs have

Melissa H. Stigler, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Emily Neusel, been developed for and delivered in middle schools; programs

M.P.H.; and Cheryl L. Perry, Ph.D. aimed at elementary schools (especially grades 3 to 5) and

high schools are less common (Spoth et al. 2008, 2009). Of

Schools are an important setting for interventions aimed at particular concern to contemporary research with underage

preventing alcohol use and abuse among adolescents. A range youth is heavy drinking, including harmful behaviors, such

of schoolbased interventions have been developed to prevent as binge drinking and drunkenness.

or delay the onset of alcohol use, most of which are targeted The primary goal of schoolbased alcohol prevention

to middleschool students. Most of these interventions seek to programs is to prevent or delay the onset of alcohol use,

reduce risk factors for alcohol use at the individual level, although some programs also seek to reduce the overall

whereas other interventions also address social and/or prevalence of alcohol use. Interventions earlier in life

environmental risk factors. Not all interventions that have (i.e., during elementary school) target risk factors for later

been developed and implemented have been found to be alcohol use (e.g., early aggression) because alcohol use

effective. Indepth analyses have indicated that to be most itself is not yet relevant to this age group (Spoth et al.

effective, interventions should be theory driven, address social 2008, 2009). Any reduction in alcoholrelated behavior is

norms around alcohol use, build personal and social skills assumed to lead to subsequent reductions in alcoholrelated

helping students resist pressure to use alcohol, involve problems (e.g., injuries or alcohol dependence), although

interactive teaching approaches, use peer leaders, integrate the latter often are not measured in primary prevention

other segments of the population into the program, be studies (Foxcroft et al. 2002).

delivered over several sessions and years, provide training Schoolbased alcohol interventions are designed to reduce

and support to facilitators, and be culturally and risk factors for early alcohol use primarily at the individual

developmentally appropriate. Additional research is needed level (e.g., by enhancing student’s knowledge and skills),

to develop interventions for elementaryschool and high although the most successful schoolbased programs address

school students and for special populations. KEY WORDS: social and environmental risk factors (e.g., alcoholrelated

Alcohol and other drug use (AODU); alcohol consumption; norms) as well. Some schoolbased programs focus on the

alcohol abuse; age of AODU onset; underage drinking; general population of adolescents (i.e., are universal pro

adolescent; risk factors; individual risk factors; social grams), whereas others target adolescents who are particu

environmental risk factors; elementary school; middle school; larly at risk (i.e., are selective or indicated programs). The

high school; schoolbased prevention; schoolbased intervention research literature on the efficacy of schoolbased alcohol

prevention programs is large, encompassing several decades

of study (Foxcroft et al. 2002; Komro and Toomey 2002;

B

ecause alcohol use typically begins during adolescence Spoth et al. 2008, 2009). The most recent review by Spoth

(Office of the Surgeon General 2006) and because no and colleagues (2008, 2009) provides several examples of

other community institution has as much continuous effective schoolbased programs, which will be discussed

and intensive contact with underage youth, schools can be in detail below. Not all schoolbased alcohol prevention

an important setting for intervention. This article describes programs for youth are effective, however. The review by

schoolbased approaches to alcohol prevention, highlighting Foxcroft and colleagues (2002), especially, emphasizes this

evidencebased examples of this method of intervention, and point with regard to longterm (3 years or more) outcomes

suggests directions for future research. This summary primarily of primary prevention efforts such as schoolbased programs.

is based on several recent reviews focusing on alcohol preven

tion among underage youth conducted by Foxcroft and col

leagues (2002), Komro and Toomey (2002), and—the most Examples of EvidenceBased, SchoolBased

comprehensive and critical review of this field to date—Spoth Alcohol Prevention Programs

and colleagues (2008, 2009). Although these previous reviews The review by Spoth and colleagues (2008, 2009) provides

addressed interventions in a variety of contexts (e.g., families, support for the efficacy of schoolbased programs, at least in

schools, and communities), the present article highlights key the short term (defined as at least 6 months after the inter

findings specific to schoolbased interventions. vention was implemented). This review considered alcohol

Characteristics of SchoolBased Alcohol MELISSA H. STIGLER, PH.D., M.P.H., is an assistant professor,

Prevention Programs EMILY NEUSEL, M.P.H., is a graduate assistant, and CHERYL

L. PERRY, PH.D., is a professor and regional dean at the Michael

Rates of initiation of drinking rise rapidly starting at age 10 & Susan Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living, School

(i.e., grades 4 and 5) and peak between ages 13 and 14 (i.e., of Public Health, University of Texas, Austin and Houston, Texas.

Vol. 34, No. 2, 2011 157

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

prevention interventions across three developmental periods

(i.e., younger than age 10 years, age 10 to 15 years, and age

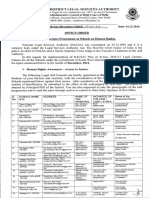

16 years or older), aligned with reviews of other etiologic Table The Most Promising SchoolBased Alcohol Prevention

Interventions Identified by Spoth and Colleagues (2008, 2009)

work during the same developmental stages (Masten et al.

2009; Zucker et al. 2009). Of more than 400 studies that

the investigators screened, only 127 interventions could be Children younger than 10 years of age

evaluated for their efficacy according to the inclusion criteria Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers

specified by the researchers. Of these 127 studies, 41 showed Raising Healthy Children

evidence of a positive effect—that is, they could be classified Seattle Social Development Project

as “most promising” (n = 12) or having “mixed or emerging”

evidence (n = 29). A list of the schoolbased interventions

Adolescents ages 10 to 15 years

identified as most promising is provided in the table.

Twothirds of the mostpromising interventions that keepin’ it REAL

were identified by Spoth and colleagues (2008, 2009) Midwestern Prevention Project/Project STAR

either were exclusively school based (n = 2) or included a Project Northland

large schoolbased component within a multiplecompo

nent or multipledomain intervention (n = 6). Most Older participants ages 16 to more than 20 years

promising interventions were identified for all three age Project Toward No Drug Abuse

groups studied. At the elementaryschool level, interven

tions classified as most promising included the following:

interventions either were exclusively school based (n = 11)

• Seattle Social Development Project (Hawkins et al. 1991,

1992); or included a schoolbased component (n = 6). (See the

review by Spoth and colleagues [2008, 2009], as well as

• Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (Eddy et the original literature cited above for a more detailed

al. 2000, 2003); description of these interventions.)

Although the review by Spoth and colleagues (2008,

• Raising Healthy Children (Brown et al. 2005; Catalano 2009) offers concrete examples of evidencebased inter

et al. 2003); and ventions, it does not address why some schoolbased

• Preventive Treatment Program (Tremblay et al. 1996). interventions were effective and others were not. Other

recent literature reviews (Cuijpers 2002; Komro and

At the middleschool level, the most promising inter Toomey 2002) and metaanalyses (e.g., Roona et al. 2003;

ventions included the following: Tobler et al. 2000) have examined this issue. The findings

suggest that the following elements are essential to devel

• Project Northland (Perry et al. 1996, 2002); oping and implementing effective schoolbased alcohol

prevention interventions:

• Project STAR, or Midwestern Prevention Project (Chou

et al. 1998; Pentz et al. 1989, 1990); and • The interventions are theory driven, with a particular

• keepin’ it REAL (Hecht et al. 2003). focus on the socialinfluences model, which emphasizes

helping students identify and resist social influences

At the highschool level, only the Project Toward No (e.g., by peers and media) to use alcohol.

Drug Abuse (Sussman et al. 2002) was classified as most

promising, although Project Northland also has been • The interventions address social norms around alcohol

implemented and shown to be successful with highschool use, reinforcing that alcohol use is not common or

students (Perry et al. 2002). acceptable among youth.

Other schoolbased programs that may be familiar to

readers who conduct research in this area, such as Promoting • The interventions build personal and social skills that

Alternative Thinking Strategies (Kam et al. 2004; Riggs et

help students resist pressure to use alcohol.

al. 2006), Life Skills Training (Botvin et al. 1995; Spoth

et al. 2005), and Project Alert (Ellickson and Bell 1990;

Ellickson et al. 2003) were identified as either having • The interventions use interactive teaching techniques (e.g.,

mixed (e.g., Life Skills Training, Project Alert) or emerging smallgroup activities and role plays) to engage students.

(e.g., Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) evidence,

along with 26 other interventions (Spoth et al. 2008, • The interventions use sameaged students (i.e., peer leaders)

2009). Seventeen of 29 “mixed or emerging evidence” to facilitate delivery of the program.

158 Alcohol Research & Health

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

• The interventions integrate additional components to in the previous month, and onethird were drunk in the last

connect other segments of the community (e.g., parents) month (Johnston et al. 2010). Accordingly, sustained inter

to the program. vention throughout high school likely is necessary to main

tain any changes in developmental trajectories of alcohol use

• The interventions are conducted across multiple sessions achieved through interventions delivered in middle school, as

and multiple years to ensure that an adequate “dose” of was demonstrated by the highschool component of Project

prevention is received by students and schools. Northland (Perry et al. 2002). Further efforts to curb more

problematic patterns of alcohol use, such as binge drinking,

• The interventions provide adequate training and support also are warranted during this period (Spoth et al. 2008).

for program facilitators (i.e., teachers, students). Additional efforts to design, develop, and test school

based interventions for younger agegroups (e.g., “tweens”)

• The interventions are both culturally and developmentally are needed as well, given that schoolbased interventions

appropriate for the students they serve. seem to be most efficacious when delivered as a primary

prevention program, with the strongest effects found in

Two projects that are examples of programs meeting the youth who have not yet begun to experiment with alcohol

criteria noted above are Project Northland (Perry et al. (Perry et al. 1996). Early onset of alcohol use during the

1996, 2002) and Communities that Care (Hawkins et al. teen or preteen years is of great concern because it can

2009). These communitywide programs used evidence

have substantial physical, social, and emotional health

based school curricula, supplemented with parental

involvement, peer leadership, and community action to consequences for children and adolescents (e.g., Ellickson

achieve reductions in the onset of alcohol use in early et al. 2003; Grant and Dawson 1997), including impair

adolescence. Communities that Care is described in more ment of key brain functions and development (Squeglia

detail in the article by Fagan and colleagues (pp. 167–174, et al. 2009). Of note, a large proportion of young adoles

in this issue) that focuses on communitybased preventive cents use or begin to use alcohol before middle school.

interventions. For example, in Project Northland Chicago, 17 percent

of these urban sixth graders had started drinking alcohol

before they entered middle school (Pasch et al. 2009), and

Future Directions for SchoolBased the proportion was even higher (i.e., 37 percent) in rural

Alcohol Prevention Interventions Minnesota, in the original Project Northland; moreover,

these students were much less responsive to the interven

Although the understanding of effective interventions to pre tion than students who had not begun drinking (Perry et

vent underage alcohol use has grown substantially over the al. 1996). These high rates of early alcohol use make it

last few decades, especially for schoolbased approaches, worthwhile to introduce earlier, universal approaches to

additional research is warranted to fill remaining gaps in the alcohol prevention. For example, Spoth and colleagues

knowledge base. For example, the existing literature does not (2008) suggested intervening in grades 3, 4, and 5; how

include sufficient evidence to support or refute the short or ever, none of the existing schoolbased programs aimed

longterm efficacy of schoolbased interventions in elementary

at the later elementaryschool years met the criteria for

or highschool settings and does not fully address interven

inclusion in their review.

tions for special populations, including culturally specific

programming. These points are considered in more detail

below as suggestions for future directions for schoolbased SchoolBased Interventions for Special Populations

research. Readers are directed to the reviews by Spoth and To date, the large majority of schoolbased interventions

colleagues (2008, 2009) for additional discussion of needed have been implemented with primarily White urban and

improvements in conducting and reporting this research. suburban youth. The problem of alcohol use, however, is

not limited to these populations. Alcohol use rates among

SchoolBased Interventions for ElementarySchool and schoolgoing youth often are higher in rural settings, espe

HighSchool Settings cially rates of binge drinking (i.e., five or more drinks in one

As noted above, the majority of schoolbased alcohol preven sitting in the last 2 weeks) and drunkenness (Johnston et al.

tion interventions have been conducted in middle schools. 2010). With respect to ethnic groups, rates of alcohol use

By comparison, far fewer interventions have been developed among Hispanic eighth graders exceed those of White eighth

for elementary schools and high schools. In the review by graders, followed by African Americans (Johnston et al. 2010).

Spoth and colleagues (2008), only one schoolbased inter Accordingly, the need for alcohol use prevention interven

vention for highschool students could be classified as most tions tailored for these special populations is great. Although

promising, and only one could be classified as having mixed the body of research on this topic is growing, it requires even

or emerging evidence. However, alcohol use is particularly more attention. As Schinke and colleagues (2000) noted in

problematic during the highschool years. Nationwide, a Cochrane review, culturally focused interventions may be

almost half of highschool seniors report consuming alcohol an especially valuable approach to intervention over the long

Vol. 34, No. 2, 2011 159

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

term. However, additional development and rigorous evalua cessfully—need to be considered carefully as translation

tion of this approach is required (Foxcroft et al. 2002). research unfolds.

In their review, Spoth and colleagues (2008) identified A final program worthy of note is Drug Abuse Resistance

a few schoolbased alcohol prevention interventions Education (D.A.R.E.). Although reviews of this program

specifically designed for special populations (e.g., minority consistently show that it has little if any impact on alcohol

youth, rural youth) with promising or emerging evidence. and drug use (Ennett et al. 1994), it continues to be widely

For example, keepin’ it REAL is a culturally grounded alcohol used across the United States. To capitalize on the power

prevention program developed for and tested in Mexican ful dissemination mechanism of the D.A.R.E. program,

and MexicanAmerican middleschool students (Hecht Perry and colleagues (2003) developed and evaluated

et al. 2003; Kulis et al. 2005). Instead of “translating” D.A.R.E. Plus, which was successful in reducing tobacco

an existing schoolbased program originally designed and alcohol use among boys. These positive outcomes

for majority youth for use in this population, Hecht and were attributed to the “Plus” components, such as peer

colleagues (2003) crafted a successful program grounded leadership, parental education, and neighborhood involve

from the beginning in ethnic norms and values. Their ment, because the D.A.R.E. program alone did not

multicultural version, based on Latino, EuropeanAmerican, demonstrate these outcomes (Perry et al. 2003).

and AfricanAmerican norms and values, was especially

effective at reducing alcohol use over time (Kulis et al.

2005). Approaches like these that influence the deeper

Conclusion

structure of an intervention might be necessary to effec Alcohol remains the drug of choice among America’s adoles

tively meet the needs of special populations as additional cents, with rates of current (i.e., past 30day) use that are

efforts are considered and subsequently undertaken to more than double those of cigarette smoking and rates of

adapt existing evidencebased interventions for use in annual use that far exceed the use of marijuana and other

nonmajority, understudied groups. illicit drugs (Johnston et al. 2010). Because alcohol use is

Efforts to date to translate or adapt existing evidence more prevalent, and thus more normative, it remains more

based interventions for special populations and settings resistant to change than these other types of drug use. As a

have produced mixed results (Spoth et al. 2008). For consequence, reducing underage alcohol use will require sus

example, the adaptation of Project Northland for use with tained intervention across adolescence, with added attention

a multiethnic population in Chicago was unsuccessful at given to special populations for which effective interventions

changing alcohol use behaviors among those urban middle are not yet available. Schoolbased interventions can be an

school youth (Komro et al. 2008), even though the adap effective approach to prevention, at least in the short term

tation included not only surfacestructure changes (e.g., (Komro and Toomey 2002; Spoth et al. 2008, 2009). But

changes in text and graphics) but also the deepstructure because alcohol use currently is so normative among both

changes (e.g., incorporating culturally specific values and adolescents and adults in the United States, comprehensive

norms) alluded to above (Komro et al. 2004; Resnicow et interventions that address multiple domains of a young per

al. 1999). The original Project Northland in Minnesota son’s social environment—including the family, school, and

had pursued a more proximal approach to intervention, community—likely will be required to substantially alleviate

with staff who were housed at the schools and with special this problem in the long term. Given the predominance of

emphasis given to school and afterschool–based activities, school in the lives of youth, using schools as a central coordi

supplemented with parental involvement (Perry et al. 1996). nating institution for primary prevention and linking them

The Chicago adaptation, in contrast, placed more emphasis to families, worksites, media, and community policies is an

on more distal intervention strategies, using staff who were efficient public health approach to alcohol use prevention

housed in the community and emphasizing community that also can be efficacious. ■

organization to reduce access to alcohol (Komro et al.

2008). The results achieved with the two variants of the

intervention suggest that in middleschool school students Financial Disclosure

may require a more focused, handson approach to alcohol The authors declare that they have no competing financial

prevention. On the other hand, the Chicago implementa interests.

tion may have been less successful because alcohol use was

less of a concern or priority in this population (Komro et

al. 2008). Thus, in the Minnesota sample, alcohol use was References

the most serious problem found in the region of the State

BOTVIN, G.J.; BAKER, E.; DUSENBURY, L.; ET AL. Longterm followup results

where the intervention was implemented (Perry et al. 1996), of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middleclass population.

whereas in the Chicago sample other concerns (e.g., JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 273:1106–1112, 1995.

regarding other drugs or violence) were more prominent. PMID: 7707598

Therefore, community needs, priorities, and readiness— BROWN, E.C.; CATALANO, R.F.; FLEMING, C.B.; ET AL. Adolescent substance

as well as the question of how these can be shaped suc use outcomes in the Raising Healthy Children Project: A twopart latent

160 Alcohol Research & Health

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73:699–710, special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 12:66–78,

2005. PMID: 16173857 2004. PMID:

CATALANO, R.F.; MAZZA, J.J.; HARACHI, T.W.; ET AL. Raising healthy children KOMRO, K.A., AND TOOMEY, T.L. Strategies to prevent underage drinking.

through enhancing social development in elementary school: Results after 1.5 Alcohol Research & Health 26:5–14, 2002. PMID: 12154652

years. Journal of School Psychology 41:143–164, 2003. PMID:

KOMRO, K.A.; PERRY, C.L.; VEBLENMORTENSON, S.; ET AL. Brief report: The

CHOU, C.P.; MONTGOMERY, S.; PENTZ, M.A.; ET AL. Effects of a community adaptation of Project Northland for urban youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology

based prevention program on decreasing drug use in highrisk adolescents. 29:457–466, 2004. PMID: 15277588

American Journal of Public Health 88:944–948, 1998. PMID: 9618626

KOMRO, K.A.; PERRY, C.L.; VEBLENMORTENSON, S.; ET AL. Outcomes from a

CUIJPERS, P. Effective ingredients of schoolbased drug prevention programs: A

randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent alcohol use preventive inter

systematic review. Addictive Behaviors 27:1009–1023, 2002. PMID: 12369469

vention for urban youth: Project Northland Chicago. Addiction 103:606–618,

EDDY, M.J.; REID, J.R.; AND FETROW, R.A. An elementary schoolbased pre 2008. PMID: 18261193

vention program targeting modifiable antecedents of youth delinquency and

violence: Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT). Journal of KOSTERMAN, R.; HAWKINS, J.D.; GUO, J.; ET AL. The dynamics of alcohol and

Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 8:165–176, 2000. marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence.

American Journal of Public Health 90:360–366, 2000. PMID: 10705852

EDDY, M.J.; REID, J.R., STOOLMILLER, M.; ET AL. Outcomes during middle school

for an elementary schoolbased preventive intervention for conduct problems: KULIS, S.; MARSIGLIA, F.F.; ELEK, E.; ET AL. Mexican/Mexican American ado

Followup results from a randomized trial. Behavior Therapy 34:535–552, 2003. lescents and keepin’ it REAL: An evidencebased substance use prevention pro

gram. Children and Schools 27:133–145, 2005.

ELLICKSON, P.L., AND BELL, R.M. Drug prevention in junior high: A multisite

longitudinal test. Science 247:1299–1305, 1990. PMID: 2180065 MASTEN, A.; FADEN, V.; ZUCKER, R.; ET AL. A developmental perspective on

underage alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health 32:3–15, 2009.

ELLICKSON, P.L.; MCCAFFREY, D.F.; GHOSHDASTIDAR, B.; AND LONGSHORE,

D.L. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a largescale Office of the Surgeon General. Surgeon General’s Call to Action To Prevent

trial of Project ALERT in middle schools. American Journal of Public Health Underage Drinking. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2006.

93:1830–1836, 2003. PMID: 14600049

PASCH, K.E.; PERRY, C.L.; STIGLER, M.H.; AND KOMRO, K.A. Sixth grade stu

ELLICKSON, P.L.; TUCKER, J.S.; AND KLEIN, D.J. Tenyear prospective study of dents who use alcohol: Do we need primary prevention programs for “tweens”?

public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics 111:949–955, Health Education & Behavior 36:673–695, 2009. PMID: 18303109

2003. PMID: 12728070

PENTZ, M.A.; DWYER, J.H.; MACKINNON, D.P.; ET AL. A multicommunity

ENNETT, S. T.; TOBLER, N.S.; RINGWALT, C. L.; AND FLEWELLING, R.L. How trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse. Effects on drug use preva

effective is Drug Abuse Resistance Education? A metaanalysis of Project DARE

lence. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 261:3259–3266,

outcome evaluations. American Journal of Public Health 84:1394–1401, 1994.

1989. PMID: 2785610

PMID: 8092361

PENTZ, M.A.; TREBOW, E.A.; HANSEN, W.B.; ET AL. Effects of a program

FOXCROFT, D.R.; IRELAND, D.; LISTERSHARP, D.J.; ET AL. Primary prevention

for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, implementation on adolescent drug use behavior: The Midwestern Prevention

3:CD003024, 2002. PMID: 12137668 Project (MPP). Evaluation Review 14:264–189, 1990.

GRANT, B.F., AND DAWSON, D.A. Age at onset of alcohol use and its associa PERRY, C.L.; KOMRO, K.A.; VEBLENMORTENSON, S.; ET AL. A randomized

tion with DSMIV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National controlled trial of the middle and junior high school D.A.R.E. and D.A.R.E

Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Plus programs. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 157:178–184,

9:103–110, 1997. PMID: 9494942 2003. PMID: 12580689

HAWKINS, J.D.; CATALANO, R.F.; MORRISON, D.M.; ET AL. The Seattle Social PERRY, C.L.; WILLIAMS, C.L.; KOMRO, K.A.; ET AL. Project Northland: Long

Development Project: Effects of the first four years on protective factors and term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health

problem behaviors. In: McCord, J., and Tremblay, R.E., Eds. Preventing Education Research 17:117–132, 2002. PMID: 11888042

Antisocial Behavior: Interventions From Birth Through Adolescence. New York:

Guilford Press; 1992, pp 139–162. PERRY, C.L.; WILLIAMS, C.L.; VEBLENMORTENSON, S.; ET AL. Project Northland:

Outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early ado

HAWKINS, J.D.; OESTERLE, S.; BROWN, E.C.; ET AL. Results of a type 2 transla lescence. American Journal of Public Health 86:956–965, 1996. PMID: 8669519

tional research trial to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency: A test of

Communities That Care. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine RESNICOW, K.; SOLER, R.E.; BRAITHWAITE, R.L.; ET AL. Development of a

163:789–798, 2009. PMID: 19736331 racial and ethnic identity scale for African American adolescents: The Survey of

Black Life. Journal of Black Psychology 25:171–188, 1999.

HAWKINS, J.D.; VON CLEVE, E.; AND CATALANO, R.F., JR. Reducing early child

hood aggression: Results of a primary prevention program. Journal of the American RIGGS, N.R.; GREENBERG, M.T.; KUSCHE, C.A.; AND PENTZ, M.A. The medi

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:208–217, 1991. PMID: 2016224 tational role of neurocognition in the behavioral outcomes of a socialemotional

prevention program in elementary school students: Effects of the PATHS cur

HECHT, M.L.; MARSIGLIA, F.F.; ELEK, E.; ET AL. Culturally grounded substance

use prevention: An evaluation of the Keepin’ it R.E.A.L. curriculum. Preventive riculum. Prevention Science 7:91–102, 2006. PMID: 16572300

Science 4:233–248, 2003. PMID: 1458996 ROONA, M.R.; STREKE, A.V.; AND MARSHALL, D.G. Substances, adolescence

JOHNSTON, L.D.; O’MALLEY, P.M.; BACHMAN, J.G.; AND SCHULENBERG, J.E. (metaanalysis). In: Gulotta, T.P., and Bloom, M., Eds. Encyclopedia of Primary

Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2009: Volume Prevention and Health Promotion. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum

I, Secondary School Students. NIH Publication No. 10–7584. Bethesda, MD: Publishers, 2003, pp. 1065–1079.

National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010. PMID:

SCHINKE, S.P.; TEPAVAC, L.; AND COLE, K.C. Preventing substance use among

KAM, C.; GREENBERG, M.T.; AND KUSCHE, C.A. Sustained effects of the Native American youth: Threeyear results. Addictive Behaviors 25:387–397,

PATHS curriculum on the social and psychological adjustment of children in 2000. PMID: 10890292

Vol. 34, No. 2, 2011 161

TARGETED PREVENTION APPROACHES—WHAT WORKS

SPOTH, R.; GREENBERG, M.; AND TURRISI, R. Preventive interventions address SUSSMAN, S.; DENT, C.W.; AND STACY, A.W. Project Towards No Drug

ing underage drinking: State of the evidence and steps toward public health Abuse: A review of the findings and future directions. American Journal of

impact. Pediatrics 121:S311–S336, 2008. PMID: 18381496 Health Behavior 26:354–365, 2002. PMID: 12206445

SPOTH, R.; GREENBERG, M.; AND TURRISI, R. Overview of preventive interven TOBLER, N.S.; ROONA, M.R.; OCHSHORN, P.; ET AL. Schoolbased adolescent

tion addressing underage drinking: State of the evidence and steps toward pub drug prevention programs: 1998 metaanalysis. Journal of Primary Prevention

lic health impact. Alcohol Research & Health 32:53–66, 2009.

20:275–336, 2000.

SPOTH, R.; RANDALL, G.K.; SHIN, C.; AND REDMOND, C. Randomized study

TREMBLAY, R.E.; MASSE, L.; PAGANI, L.; ET AL. From childhood physical aggres

of combined universal family and school preventive interventions: Patterns of

longterm effects on initiation, regular use, and weekly drunkenness. Psychology sion to adolescent maladjustment: The Montreal Prevention Experiment. In:

of Addictive Behaviors 19:372–381, 2005. PMID: 16366809 Peters, R.D., and McMahon, R.J., Eds. Preventing Childhood Disorders, Substance

Abuse, and Delinquency. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996, pp. 268–298.

SQUEGLIA, L.M.; JACOBUS, J.; AND TAPERT, S.F. The influence of substance use

on adolescent brain development. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience 40:31–38, ZUCKER, R.; DONOVAN, J. E.; MASTEN, A.; ET AL. Developmental processes

2009. PMID: 19278130 and mechanisms: Ages 0–10. Alcohol Research & Health 32:16–32, 2009.

Now Available From NIAAA

Beyond Hangovers

NIAAA

understanding alcohol’s

impact on your health

Beyond Hangovers presents

information on alcohol’s

effects on the human body,

including the heart, liver,

brain, and pancreas. This

publication also features

alcohol’s lesserknown

effects, such as those relating

to cancer risks and immune

system function.

U.S. Department

of Health and

Human Services

To order, write to: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism,

National Institutes Publications Distribution Center, P.O. Box 10686, Rockville, MD 20849–0686,

of Health

or fax: (703) 312–5230 or phone: 1–888–MY–NIAAA. Full text also is available

on NIAAA’s Web site (www.niaaa.nih.gov).

162 Alcohol Research & Health

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Classroom Evaluation ChecklistDocumento3 pagineClassroom Evaluation ChecklistAngelaLomagdong94% (18)

- Study PlanDocumento2 pagineStudy Planrizqullhx100% (1)

- Grey Lit Summary v3FINAL PDFDocumento5 pagineGrey Lit Summary v3FINAL PDFmarzelsantosNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Number of Hours Spent For StudyingDocumento35 pagineOn The Number of Hours Spent For StudyingJiordan Simon67% (3)

- Manasi Patil - Why Read Shakespeare Complete Text Embedded Work MasterDocumento8 pagineManasi Patil - Why Read Shakespeare Complete Text Embedded Work Masterapi-3612704670% (1)

- OutLines of European Board Exam-HNS - ExamDocumento19 pagineOutLines of European Board Exam-HNS - ExamDrMohmd ZidaanNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Abuse - SummativeDocumento6 pagineDrug Abuse - SummativeSofia TelidouNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevención en El AcosoDocumento31 paginePrevención en El AcosoRicard SanromaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sawyer 2010Documento11 pagineSawyer 2010Đan TâmNessuna valutazione finora

- P45003 - Assignment 2Documento18 pagineP45003 - Assignment 2Sofia TelidouNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Chapter 1 5Documento14 pagineThesis Chapter 1 5Felicity Mae Dayon BaguioNessuna valutazione finora

- Predicting Teachers' and Schools' Implementation of The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: A Multilevel StudyDocumento31 paginePredicting Teachers' and Schools' Implementation of The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: A Multilevel StudyandreioanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2012 TEESSON Programas Australianos de Alcohol y DrogasDocumento6 pagine2012 TEESSON Programas Australianos de Alcohol y DrogaspilarNessuna valutazione finora

- Alainne Cortez 2Documento14 pagineAlainne Cortez 2Allen CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- Artigo EJPE 2016Documento19 pagineArtigo EJPE 2016lucimaramcarNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Prevention Programmes in Schools: What Is The Evidence?Documento31 pagineDrug Prevention Programmes in Schools: What Is The Evidence?AB-Nessuna valutazione finora

- LiteratureDocumento6 pagineLiteratureReshel Mae PontoyNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0022440503000311 MainDocumento22 pagine1 s2.0 S0022440503000311 MainAzmil XinanNessuna valutazione finora

- Berry et al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)Documento59 pagineBerry et al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)ceglarzsabiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Bullying Intervention System in High School A Two-Year School-Wide Follow-UpDocumento10 pagineA Bullying Intervention System in High School A Two-Year School-Wide Follow-UpLorenzoNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevention Programs in SchoolsDocumento16 paginePrevention Programs in Schoolsapi-383927705Nessuna valutazione finora

- Effective Elements of School Health Promotion Across BehavioralDocumento15 pagineEffective Elements of School Health Promotion Across Behavioraldavid_aguirre_herrerNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Differences in Respect To Self-Esteem and Body Image As Well As Response To Adolescents' School-Based Prevention ProgramsDocumento10 pagineGender Differences in Respect To Self-Esteem and Body Image As Well As Response To Adolescents' School-Based Prevention ProgramsEnrique Lugo RoblesNessuna valutazione finora

- OBPP Implementation and Evaluation Over Two DecadesDocumento60 pagineOBPP Implementation and Evaluation Over Two DecadesDedi AriwibowoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Article 91Documento12 pagine2016 Article 91Asty Leti CuekzzNessuna valutazione finora

- Should Harm Minimization As An Approach To Adolescent Substance Use Be Embraced by Junior High Schools...Documento12 pagineShould Harm Minimization As An Approach To Adolescent Substance Use Be Embraced by Junior High Schools...Ign EcheverríaNessuna valutazione finora

- Olweus LImber 2010 ADocumento27 pagineOlweus LImber 2010 Agabrielamonicabiris77Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reduction of Alcohol-Related Harm On United States College Campuses: The Use of Personal Feedback InterventionsDocumento10 pagineReduction of Alcohol-Related Harm On United States College Campuses: The Use of Personal Feedback InterventionsMilicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dropout Prevention Programs: Effects on Completion and Dropout RatesDocumento35 pagineDropout Prevention Programs: Effects on Completion and Dropout RatesAnna MaryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Resilience and Emotional WellbeingDocumento19 pagineResilience and Emotional Wellbeingstephen changayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of "Healthy Way To Grow": An Obesity Prevention Program in Early Care and Education CentersDocumento14 pagineEvaluation of "Healthy Way To Grow": An Obesity Prevention Program in Early Care and Education Centersapi-725875845Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2Documento19 pagine2didiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Typology For Campus-Based Alcohol Prevention: Moving Toward Environmental Management StrategiesDocumento42 pagineA Typology For Campus-Based Alcohol Prevention: Moving Toward Environmental Management StrategiesroshaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Educ. Res. 2003 Connelly 664 77Documento14 pagineHealth Educ. Res. 2003 Connelly 664 77Andreea PaduretNessuna valutazione finora

- Practitioner Review: Twenty Years of Research With Adverse Childhood Experience Scores - Advantages, Disadvantages and Applications To PracticeDocumento15 paginePractitioner Review: Twenty Years of Research With Adverse Childhood Experience Scores - Advantages, Disadvantages and Applications To PracticeMarlon Daniel Torres PadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Promotion Interventions For Children and Adolescents Using An Ecological FrameworkDocumento14 pagineSystematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Promotion Interventions For Children and Adolescents Using An Ecological FrameworkFikran Ahmad Ahmad Al-HadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Signatureassignment HesseDocumento20 pagineSignatureassignment Hesseapi-248025679Nessuna valutazione finora

- Artigo SobreDocumento16 pagineArtigo SobreMarina HeinenNessuna valutazione finora

- Archibald TrudDocumento8 pagineArchibald TrudNatasa PeovskaNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Psychosocial Problems of School Aged Youth: Developmental Variations, Problems, Disorders and Perspectives For Prevention and TreatmentDocumento229 pagineCommon Psychosocial Problems of School Aged Youth: Developmental Variations, Problems, Disorders and Perspectives For Prevention and TreatmentNg Huah LinNessuna valutazione finora

- Long-Term Benefits of Head Start Early Childhood ProgramDocumento24 pagineLong-Term Benefits of Head Start Early Childhood ProgramAlinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Olweus Bulying 2Documento26 pagineOlweus Bulying 2Szandor X. Lecter-LaVeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Coping Skills AdolescentsDocumento19 pagineCoping Skills AdolescentsZayra UribeNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Abuse Prevention StrategyDocumento5 pagineDrug Abuse Prevention Strategyiulia9gavrisNessuna valutazione finora

- BASE SCOTT, 2010 Impact of A Parenting Program in A High-Risk, Multi-Ethnic CommunityDocumento11 pagineBASE SCOTT, 2010 Impact of A Parenting Program in A High-Risk, Multi-Ethnic CommunityDoniLeiteNessuna valutazione finora

- Aba Vs TeaachDocumento16 pagineAba Vs TeaachkalidasspramkumarNessuna valutazione finora

- School-Based Interventions For Students With or atDocumento11 pagineSchool-Based Interventions For Students With or atantoniodhani.adNessuna valutazione finora

- s11482 018 9632 1Documento19 pagines11482 018 9632 1Nabilah farahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: Implementation and Evaluation Over Two DecadesDocumento27 pagineThe Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: Implementation and Evaluation Over Two DecadesStefania SaftaNessuna valutazione finora

- Body Mass Index and Dental Caries in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Literature Published 2004 To 2011Documento26 pagineBody Mass Index and Dental Caries in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Literature Published 2004 To 2011norma paulina carcausto lipaNessuna valutazione finora

- Two-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsDocumento16 pagineTwo-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsJuliana ZardiniNessuna valutazione finora

- An Econometric Analysis of Anti-Bullying Program FactorsDocumento14 pagineAn Econometric Analysis of Anti-Bullying Program FactorsLucas Jean de Miranda CoelhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Olweus LImber 2010 ADocumento27 pagineOlweus LImber 2010 ARiski Octavia Nawang SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Midwestern Prevention Project: TJ Davis Loras College CRJ 312: Crime Prevention Professor Loui December 2, 2020Documento9 pagineMidwestern Prevention Project: TJ Davis Loras College CRJ 312: Crime Prevention Professor Loui December 2, 2020api-547413934Nessuna valutazione finora

- Expert and Stakeholder Consensus On Priorities For Obesity Prevention Research in Early Care and Education SettingsDocumento10 pagineExpert and Stakeholder Consensus On Priorities For Obesity Prevention Research in Early Care and Education Settingsparanoea911Nessuna valutazione finora

- Triple PEvaluationDocumento19 pagineTriple PEvaluationEncep SukandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion Paper Series: The Causal Effect of Education On Chronic Health ConditionsDocumento27 pagineDiscussion Paper Series: The Causal Effect of Education On Chronic Health ConditionsMerna YasserNessuna valutazione finora

- Carvalho Marques Pinto Maroco 2017 MindfulnessDocumento14 pagineCarvalho Marques Pinto Maroco 2017 MindfulnessNicole RichardsonNessuna valutazione finora

- PB15-Caring For ChildrenDocumento4 paginePB15-Caring For ChildrenMahmoud FawzyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Prevention of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analytic ReviewDocumento15 pagineThe Prevention of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analytic ReviewChristine BlossomNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Drug Abuse Prevention StrategiesDocumento90 pagineImpact of Drug Abuse Prevention StrategiesLi An Rill100% (1)

- C Boustani, M. M., Frazier, S. L., Becker, K. D., Bechor, M., Dinizulu, S. M., Hedemann, E. R., ... & Pasalich, D. S. (2015) .Documento11 pagineC Boustani, M. M., Frazier, S. L., Becker, K. D., Bechor, M., Dinizulu, S. M., Hedemann, E. R., ... & Pasalich, D. S. (2015) .Ign EcheverríaNessuna valutazione finora

- It Is Possible!: PRINCIPLES OF MENTORING YOUNG & EMERGING ADULTS, #1Da EverandIt Is Possible!: PRINCIPLES OF MENTORING YOUNG & EMERGING ADULTS, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- TESOL Methodology MOOC Syllabus: Course Dates: January 27 - March 2, 2020Documento7 pagineTESOL Methodology MOOC Syllabus: Course Dates: January 27 - March 2, 2020Younus AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- References For RationaleDocumento2 pagineReferences For Rationaleapi-545815812Nessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting "Entrepreneurial Culture": The Mediating Role of CreativityDocumento21 pagineFactors Affecting "Entrepreneurial Culture": The Mediating Role of CreativitySalsabila BahariNessuna valutazione finora

- Rena Subotnik, Lee Kassan, Ellen Summers, Alan Wasser - Genius Revisited - High IQ Children Grown Up-Ablex Publishing Corporation (1993)Documento149 pagineRena Subotnik, Lee Kassan, Ellen Summers, Alan Wasser - Genius Revisited - High IQ Children Grown Up-Ablex Publishing Corporation (1993)Pablo SantanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Health 5 LAS Quarter 3Documento31 pagineHealth 5 LAS Quarter 3Josephine Acio100% (4)

- Cognitive Components of Social AnxietyDocumento4 pagineCognitive Components of Social AnxietyAdina IlieNessuna valutazione finora

- Databaseplan 1Documento3 pagineDatabaseplan 1api-689126137Nessuna valutazione finora

- Summary 6Documento5 pagineSummary 6api-640314870Nessuna valutazione finora

- GITAM University: (Faculty Advisor) (CSI Coordinator)Documento3 pagineGITAM University: (Faculty Advisor) (CSI Coordinator)Kireeti Varma DendukuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study No.3 Selection of EmployeeDocumento2 pagineCase Study No.3 Selection of Employeesanta lizardo100% (2)

- Student Profiles PGP 16 IIM Kozhikode PDFDocumento88 pagineStudent Profiles PGP 16 IIM Kozhikode PDFvivekNessuna valutazione finora

- Abigail Pelletier Teaching ResumeDocumento4 pagineAbigail Pelletier Teaching Resumeapi-253261843Nessuna valutazione finora

- Enter Ghosts. The Loss of Intersubjectivity in Clinical Work With Adult Children of Pathological Narcissists .Documento14 pagineEnter Ghosts. The Loss of Intersubjectivity in Clinical Work With Adult Children of Pathological Narcissists .Willem OuweltjesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Deomo Taxonomy CodeDocumento6 pagineA Deomo Taxonomy CodeDustin AgsaludNessuna valutazione finora

- Hiding Behind The Bar-1!12!29-09Documento7 pagineHiding Behind The Bar-1!12!29-09udhayaisro100% (1)

- The Eleven Principles of Leadership PDFDocumento1 paginaThe Eleven Principles of Leadership PDFMwanja MosesNessuna valutazione finora

- CSC 520 AI 2018 Spring SyllabusDocumento7 pagineCSC 520 AI 2018 Spring SyllabusscribdfuckuNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal Awareness Programmes at Schools On Human RightsDocumento2 pagineLegal Awareness Programmes at Schools On Human RightsSW-DLSANessuna valutazione finora

- PDNE With PDLNE PDFDocumento46 paginePDNE With PDLNE PDFJamshihas ApNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Phase 1 - Terminology of Language TeachingDocumento4 pagineActivity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Phase 1 - Terminology of Language TeachingMaria Paula PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Empirical evidence supports higher-order consciousness theoriesDocumento9 pagineEmpirical evidence supports higher-order consciousness theorieskarlunchoNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Output For Title DefenseDocumento6 pagineWritten Output For Title DefensebryanNessuna valutazione finora

- PRE SCHOOL BTHO FEE 2022 - LatestDocumento1 paginaPRE SCHOOL BTHO FEE 2022 - LatestWira Hazwan RosliNessuna valutazione finora

- Blacklight Dress Rehearsal and Tentative Final PerformanceDocumento5 pagineBlacklight Dress Rehearsal and Tentative Final Performanceapi-496802644Nessuna valutazione finora

- UK Medical Schools - Admissions Requirements 2013Documento7 pagineUK Medical Schools - Admissions Requirements 2013CIS AdminNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit - 3: Losses and Efficiency of DC MachinesDocumento4 pagineUnit - 3: Losses and Efficiency of DC MachinesNisha JosephNessuna valutazione finora