Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy

Caricato da

opi akbarCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy

Caricato da

opi akbarCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research

JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery | Original Investigation

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy

for Chronic Rhinosinusitis Due to Staphylococcus aureus

Mian Li Ooi, MBBS; Amanda Jane Drilling, PhD; Sandra Morales, PhD; Stephanie Fong, MBBS; Sophia Moraitis, BMedSc;

Luis Macias-Valle, MD; Sarah Vreugde, MD, PhD; Alkis James Psaltis, MBBS, PhD, FRACS; Peter-John Wormald, MD, FRACS

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE Staphylococcus aureus infections are associated with recalcitrant chronic

rhinosinusitis (CRS). The emerging threat of multidrug-resistant S aureus infections has

revived interest in bacteriophage (phage) therapy.

OBJECTIVE To investigate the safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of ascending

multiple intranasal doses of investigational phage cocktail AB-SA01 in patients with

recalcitrant CRS due to S aureus.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This phase 1, first-in-humans, open-label clinical trial of

multiple ascending doses was conducted at a single tertiary referral center from December 1,

2015, through September 30, 2016, with follow-up completed on December 31, 2016.

Patients with recalcitrant CRS (aged 18-70 years) in whom surgical and medical treatment had

failed and who had positive S aureus cultures sensitive to AB-SA01 were recruited. Findings

were analyzed from February 2 through August 31, 2017.

INTERVENTIONS Three patient cohorts (3 patients/cohort) received serial doses of twice-daily

intranasal irrigations with AB-SA01 at a concentration of 3 × 108 plaque-forming units (PFU)

for 7 days (cohort 1), 3 × 108 PFU for 14 days (cohort 2), and 3 × 109 PFU for 14 days

(cohort 3).

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary study outcome was the safety and tolerability

of intranasal AB-SA01. Safety observations included vital signs, physical examinations,

clinical laboratory test results, and adverse events. The secondary outcome was preliminary

efficacy assessed by comparing pretreatment and posttreatment microbiology results,

disease-relevant endoscopic Lund-Kennedy Scores, and symptom scores using a visual

analog scale and Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22.

RESULTS All 9 participants (4 men and 5 women; median age, 45 years [interquartile range,

41.0-71.5 years]) completed the trial. Intranasal phage treatment was well tolerated, with no

serious adverse events or deaths reported in any of the 3 cohorts. No change in vital signs

occurred before and 0.5 and 2.0 hours after administration of AB-SA01 and at the exit visit.

Author Affiliations: Department of

No changes in biochemistry were found except for 1 participant in cohort 3 who showed a Otolaryngology–Head and Neck

decrease in blood bicarbonate levels on exit visit, with normal results of physical examination Surgery, Basil Hetzel Institute for

and vital signs. All biochemistry values were normalized 8 days later. No changes in Translational Health Research, The

University of Adelaide, Adelaide,

temperature were recorded before, during, or after treatment. Six adverse effects were

Australia (Ooi, Drilling, Fong, Moraitis,

reported in 6 participants; all were classified as mild treatment-emergent adverse effects and Macias-Valle, Vreugde, Psaltis,

resolved by the end of the study. Preliminary efficacy results indicated favorable outcomes Wormald); AmpliPhi Australia, Pty

across all cohorts, with 2 of 9 patients showing clinical and microbiological evidence of Ltd, Sydney, Australia (Morales);

Department of Otolaryngology–Head

eradication of infection. and Neck Surgery, Hospital Español

de México, Facultad Mexicana de

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Intranasal irrigation with AB-SA01 of doses to 3 × 109 PFU for Medicina Universidad La Salle,

Mexico City, Mexico (Macias-Valle).

14 days was safe and well tolerated, with promising preliminary efficacy observations. Phage

Corresponding Author: Peter-John

therapy could be an alternative to antibiotics for patients with CRS.

Wormald, MD, FRACS, Basil Hetzel

Institute for Translational Health

TRIAL REGISTRATION http://anzctr.org.au identifier: ACTRN12616000002482 Research, The University of Adelaide,

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

28 Woodville Rd, Woodville South SA

JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1191 5011, Australia (peterj.wormald@

Published online June 20, 2019. adelaide.edu.au).

(Reprinted) E1

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis

T

he management of recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis

(CRS) is increasingly challenged by infections with dif- Key Points

ficult-to-treat biofilms and multidrug-resistant bacte-

Question What are the systematic safety and efficacy data

ria. Antibiotics can alleviate symptoms in acute exacerba- necessary to incorporate bacteriophage therapy as a clinical

tions of recalcitrant CRS but fail to eradicate the biofilm nidus, alternative to antibiotics?

resulting in a relapsing course of disease.1 Among patients with

Findings This first-in-humans, phase 1 trial aimed to investigate

recalcitrant CRS and failed surgical intervention, as many as

the safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of the ascending

50% of biofilms identified are dominated by Staphylococcus dose intranasal phage cocktail AB-SA01 in 9 patients with

aureus.2 With a growing prevalence of resistance to first-line recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis positive for Staphylococcus

antibiotics and lack of research and development of new aureus. Intranasal AB-SA01 was safe and well tolerated to doses of

antibiotics, novel antibiofilm agents are needed to help con- 3 × 109 plaque-forming units for 14 days, and 2 of 9 patients had

trol disease in these patients. eradication of infection.

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy was proposed as an anti- Meaning Intranasal irrigation with phage cocktail AB-SA01 is safe

bacterial treatment as early as the 1910s. Increasing interest and well tolerated at the highest study dose with promising

in its potential to treat bacterial infections has been recently preliminary efficacy results and could be a potential alternative to

driven by the exponential increase of antibiotic-resistant antibiotics for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis due to S aureus.

strains.3 Phages are viruses that infect only 1 or a few closely

related bacterial species with no pathogenic effect on mam- mine the safety and tolerability of intranasal application of the

malian cells. Phages can be divided into obligately lytic and phage cocktail AB-SA01 in patients with recalcitrant CRS due to

temperate (also called lysogenic) phages.4,5 Lytic phages S aureus. In addition, we determined the feasibility of our trial

hijack the bacterial host cellular machinery to produce prog- protocol, including preliminary efficacy assessments.

eny phages, kill the bacteria to reenter the surrounding envi-

ronment, and proceed to invade new bacterial hosts. Temper-

ate phages integrate their genome into the host genome and

remain dormant, benignly replicating with the bacteria until

Methods

triggered to enter the lytic cycle. Phage therapy uses obli- Participants and Study Design

gately lytic phages to achieve maximal bacterial elimination Ethics approval was granted by the Central Northern Adelaide

and minimize the risks for horizontal gene transfer.6,7 Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee to conduct

Phage therapy offers several potential advantages over oral the trial within its network of teaching hospitals in Adelaide,

antibiotics.8 For example, biofilms are more effectively re- Australia. All participants gave written informed consent in ac-

moved by phages9 but are more resistant to antibiotics to cordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol inclu-

1000-fold.10 Phages offer a highly specific, targeted treat- sion and exclusion criteria are outlined in eTable 1 in Supple-

ment that is expected to cause less disruption of the normal ment 1. Patients aged 18 to 70 years who gave informed consent,

microbiota than broad-spectrum antibiotics, resulting in fewer were able to comply with the trial protocol, and previously

systemic adverse effects. Phages self-replicate at the site of in- underwent endoscopic sinus surgery were included in the study

fection, reducing the need for frequent administration. Phages if they presented with an S aureus sinus infection sensitive to

can be effective against antibiotic-resistant strains such as AB-SA01. Because these participants had recalcitrant CRS with

methicillin-resistant S aureus and have the potential to alter a history of endoscopic sinus surgery, they received routine

the resistance profile of antibiotic-resistant strains.11,12 twice-daily saline irrigations before study entry.

The phage cocktail used in the present study, AB-SA01, is This prospective, open-label, phase 1 clinical trial was con-

an equipotent mixture of 3 natural lytic phages that belong to ducted at a single tertiary referral center from December 1, 2015,

the Myoviridae family. The AB-SA01 component phages are through September 30, 2016, with follow-up completed on De-

obligately lytic, are incapable of specialized transduction, con- cember 31, 2016 (the trial protocol is found in Supplement 2);

tain no known antibiotic resistance or bacterial virulence genes, findings were analyzed from February 2 through August 31, 2017.

and are capable of killing a wide range of clinical S aureus Each cohort received serial doses of AB-SA01 intranasal irriga-

strains.13 Related phages demonstrated short-term14 and tions in the following ascending dosage regimens: twice-daily

long-term 15 safety and efficacy in an established sheep intranasal irrigations of AB-SA01 at a concentration of 3 × 108

S aureus biofilm sinusitis model. plaque-forming units (PFU) for 7 days (cohort 1), 3 × 108 PFU for

As with antibiotics, S aureus can develop resistance against 14 days (cohort 2), or 3 × 109 PFU for 14 days (cohort 3).

phages, resulting in bacteriophage insensitive mutants.1 A few In cohort 1, all 3 participants received serial doses only af-

in vitro studies have shown anti–S aureus phage mixes were ter successful completion of a safety and tolerability assess-

superior to single phages because they reduce the risk of de- ment by a safety medical committee. Once treatment in co-

veloping bacteriophage-insensitive mutants16,17 and provide hort 1 was completed, the safety data were reviewed by the

a wider host range effect.18 safety medical committee before treatment in cohort 2 was

Designing and executing robust clinical trials is key to commenced. After the sentinel participant from cohort 2 was

building a greater understanding of the short- and long-term treated without safety concerns, the remaining 2 participants

clinical effects of phage therapy and required for licensure. The in cohort 2 received treatment in parallel. The use of a senti-

purpose of this first-in-human, open-label study was to deter- nel participant was then repeated for cohort 3 (Figure 1).

E2 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 (Reprinted) jamaotolaryngology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis Original Investigation Research

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Describing Participant Flow and Specific Administered Treatments

3 Cohort 1

3 × 108 PFU for 7 d

Sentinel patient 1 Patient 2 Patient 3

Intranasal irrigations

twice daily

3 Cohort 2 Patient 2

3 × 108 PFU for 14 d

9 Patients recruited Sentinel patient 1

Intranasal irrigations

twice daily Patient 3

3 Cohort 3 Patient 2

3 × 109 PFU for 14 d

Sentinel patient 1

Intranasal irrigations

twice daily Patient 3

PFU indicates plaque-forming units.

Figure 2. Flow Diagram Describing Detailed Trial Protocol at All Points of the Study

Screening visit Dosing visit Exit visit Follow-up

• Inclusion and exclusion criteria • Medical and medication histories • Temperature log reviewed • Telephone follow-up 7 d after last

reviewed reviewed • Focused physical examination dose of AB·SA01

• Consent form signed • Physical examination conducted conducted

• Demographic information • Urine pregnancy test (in WOCBP) • Endoscopic examination of sinuses

recorded conducted recorded

• Clinical laboratory tests and • Ability to self-administer nasal • Swab for bacterial culture taken

serum pregnancy test (in WOCBP) wash assessed • SNOT-22 and VAS administered

conducted • The first self-administered • Clinical laboratory tests conducted

• Endoscopic examination of dose performed in clinic and

sinuses recorded patients observed up to 30 min

• Swab for bacterial culture taken after dosing before being

• SN0T-22 and VAS administered discharged home

SNOT-22 indicates Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22; VAS, visual analog scale; and WOCBP, women of child-bearing potential.

Sensitivity of S aureus Clinical Isolates to AB-SA01 of AB-SA01. Participants performed nasal irrigations twice daily,

Patient S aureus cultures from nasal swabs were streaked on a using a new bottle to deliver each dose. All participants had

1% nutrient agar plate and grown overnight at 37 °C. Colonies to return all used or unused phage vials to the clinical trial unit

were picked using a sterile 1-μL loop and transferred to 3 mL at the exit visit to be cross-checked to ensure treatment ad-

of nutrient broth followed by incubation with shaking (180 rpm) herence. Study protocol detailing screening visit, dosing visit,

at 37 °C for 16 to 18 hours. Phage sensitivity, defined as pro- exit visit, and follow up (via telephone 7 days after exit visit)

ductive bacteriophage infection as demonstrated by the is described in Figure 2.

presence of individual phage plaques, was determined in

triplicates using the soft agar overlay technique as described Outcome Measurements for Safety

previously.3,18 ATCC 25923 was obtained from the American Biochemistry, Laboratory, and Temperature Measurements

Type Culture Collection and used as a positive control in the A panel of clinical biochemistry tests was conducted at the

assay.18 Only patients carrying a clinical isolate that was sen- screening and exit visits. Levels of hemoglobin, hematocrit,

sitive to AB-SA01 were eligible to be in the study. erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes (including eosino-

phils, neutrophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and reticulo-

Instructions to Prepare the Intranasal Sinus Lavage cytes) were included in hematology measures. Serum levels

Supplies of trial products given to participants are detailed in of urea nitrogen, creatinine, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin,

eTable 2 in Supplement 1. Investigational bacteriophage urate, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, creatine kinase, aspar-

product AB-SA01 was produced under phase-appropriate tate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, glucose, and

Good Manufacturing Practices and supplied by AmpliPhi bicarbonate were measured. Participants were asked to self-

Biosciences Corporation. monitor temperature twice daily at home and complete a tem-

The AB-SA01 vials were stored away from light and in the perature log throughout the duration of the trial to be handed

refrigerator. Prior to use, participants were asked to fill a rinse in at the exit visit.

bottle (NeilMed Pharmaceuticals) with 240 mL of Mount

Franklin Spring Water (Coca-Cola Amatil Pty Ltd) and add the Concomitant Medications

proprietary buffered salts sachets (pharmaceutical-grade All medications taken during 30 days before screening and dur-

sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate), followed by 1 mL ing the trial were recorded and reviewed. Participants using

jamaotolaryngology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 E3

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Table. Baseline Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Study Cohorta

Characteristic Cohort 1 Cohort 2 Cohort 3

Age, y 55 (52-58) 50 (39-69) 58 (37-69)

Male, No. (%) 1 (33) 0 (0) 3 (100)

History of polyposis, No. (%) 1 (33) 1 (33) 2 (67)

Frontal drill-outs, No. (%) 1 (33) 2 (67) 2 (67)

VAS scoreb 6014 (36.57-78.14) 33.76 (20.14-49.00) 29.62 (18.14-46.71)

SNOT-22 scorec 72 (45-95) 29 (26-34) 32 (8-70)

Lund-Kennedy Scored 11 (8-13) 6 (4-7) 7 (6-8)

c

Abbreviations: SNOT-22, Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22; VAS, visual analog scale. Scores range from 0 to 110, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

a d

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as median (interquartile Scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating worse endoscopic

range). disease.

b

Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

routine intranasal corticosteroids on enrollment were in- to AB-SA01 (n = 3), and study withdrawal before first treat-

structed to continue this therapy throughout the duration of ment (n = 3). The sensitivity of S aureus CRS isolates to AB-

the study, with at least 2 hours between application of the SA01 was 80% (12 of 15 isolates).

investigational drug and intranasal corticosteroids.

Tolerability, Adverse Effects, and Compliance

Clinical Examination and Adverse Events All 9 participants were adherent to the treatment protocol and

A general physical examination including vital signs (body tem- completed the trial, indicating the irrigations were well toler-

perature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) was ated, which validated the feasibility of administration route and

conducted at each dosing visit (before and 0.5 and 2.0 hours trial design. No serious adverse effects or deaths occurred, and

after dosing) and at the exit visit. Participants were assessed no adverse effect led to withdrawal of study drug treatment or

for adverse events coded using the Medical Dictionary for discontinuation from the study. A total of 6 adverse effects were

Regulatory Activities, version 2.1, for the duration of the study reported in 6 participants, all of which were classified as treat-

during clinic visits and at follow-up. ment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs). All TEAEs were of mild

severity and resolved by the end of the study. One TEAE was

Outcome Measurements for Efficacy reported in 1 of the 3 participants in cohort 1 (diarrhea). Three

Preliminary efficacy was evaluated by the semiquantitative TEAEs were reported in 2 of 3 participants in cohort 2 (epi-

assessment of pretreatment and posttreatment bacterial staxis, oropharyngeal pain, and cough). Two TEAEs were re-

cultures. Culture swabs of mucopus visualized from sinus ported in 2 of the 3 participants in cohort 3 (rhinalgia and de-

ostia or within sinuses were taken under direct endoscopic creased blood bicarbonate level). Details of adverse effects

guidance. reported are listed in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

All patients completed a symptoms score questionnaire at

every visit, using Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22 (SNOT-22)19 (22 Safety Outcomes

items, each scored from 0-5; total score range, 0-110, with No change in vital signs occurred before and 0.5 and 2.0 hours

higher scores indicating worse symptoms) and a visual ana- after administration of AB-SA01 and at the exit visit. No changes

log scale (VAS)20 (mean of 6 items scored from 0-100; total in biochemistry were found except for 1 participant in cohort 3

score range, 0-100, with higher scores indicating worse symp- who showed a decrease in blood bicarbonate levels on exit visit

toms). All patients also had entry and exit endoscopic videos with normal results of physical examination and vital signs. All

recorded and scored by an independent blinded surgeon (L.M.- biochemistry values were normalized 8 days later. No changes in

V.) using the Lund-Kennedy Score (LKS)19,21 (score range, 0-20, temperature were recorded before, during, or after treatment.

with higher scores indicating worse endoscopic disease).

Preliminary Efficacy Outcomes

Our data describe observed trends, and no statistical analysis

was performed owing to the small sample size. All patients had

Results reduction in S aureus growth, and 2 of 9 patients had nega-

A total of 9 patients completed the study (4 men and 5 wom- tive cultures after treatment. Data are summarized in eTable 4

en; median age, 45 years [interquartile range, 41.0-71.5 years]). in Supplement 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown Reduced VAS scores were found in cohorts 1 (mean differ-

in the Table. This study from December 2015 to September 2016 ence, −11.71) and 3 (mean difference, −6.25) after treatment

involved a total of 28 patients who gave written informed con- (Figure 3A and eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Cohort 2 demon-

sent, of whom 19 were excluded because of negative bacterial strated paradoxical worsening in VAS scores (mean differ-

cultures (n = 4), positive bacterial cultures with no S aureus ence, 4.81) after treatment, primarily due to a single patient

growth (n = 9), cultures positive for S aureus but insensitive (eFigure in Supplement 1).

E4 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 (Reprinted) jamaotolaryngology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis Original Investigation Research

Figure 3. Line Graph of Median Values Before and After AB-SA01 Treatment Across All Cohorts

A Visual analog scale B Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22 C Lund-Kennedy Score

80 80 80

3 × 108 PFU, 7 days (cohort 1)

3 × 108 PFU, 14 days (cohort 2)

60 60 60 3 × 109 PFU, 14 days (cohort 3)

SNOT-22 Score

VAS Score

LKS Score

40 40 40

20 20 20

0 0 0

Before After Before After Before After

Treatment Treatment Treatment Treatment Treatment Treatment

For the Lund-Kennedy Score (LKS), scores range from 0 to 20, with higher symptoms; and visual analog scale (VAS), scores range from 0 to 100, with

scores indicating worse endoscopic disease; Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22 higher scores indicating worse symptoms. PFU indicates plaque-forming units.

(SNOT-22), scores range from 0 to 110, with higher scores indicating worse

The SNOT-22 scores were reduced in cohorts 1 (mean dif- Figure 4. Three-Month Follow-up Data

ference, −8.4) and 3 (mean difference, −10) after treatment

(Figure 3B and eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Cohort 2 demon- 40

strated slightly worse scores (mean difference, 1.3) after

Before treatment

treatment. Three of the 9 patients had a minimally clinically

After treatment

important difference (>9)22 in their SNOT-22 scores (2 from 30

3-mo Follow-up

cohort 1, both with an improvement of 9 points; 1 from

cohort 1, with an improvement of 16 points). A consistent

Test Scores

trend showed improvement in endoscopic LKS across all 20

cohorts (cohort 1: mean difference, −0.6; cohort 2: mean dif-

ference, −2.6), with greatest improvement noted in cohort 3

(mean difference, −4.4) (Figure 3C and eTable 5 in Supple-

10

ment 1).

3-Month Follow-up

0

Patients who concluded the study with persistence of more VAS SNOT-22 LKS

than 2 symptoms (nasal discharge, postnasal drip, nasal ob-

struction, facial pain or pressure, and/or reduced sense of smell) For the Lund-Kennedy Score (LKS), scores range from 0 to 20, with higher

scores indicating worse endoscopic disease; Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22

with corresponding endoscopic evidence of pus after 7 days

(SNOT-22), scores range from 0 to 110, with higher scores indicating worse

from the last phage treatment dose were then given the op- symptoms; and visual analog scale (VAS), scores range from 0 to 100, with

tion of current, standard, culture-directed oral antibiotic higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

therapy. Five patients received further antibacterial treat-

ment after cessation of the study, and 4 did not. These 4 pa-

tients (1 from cohort 1, 2 with S aureus eradication from co- serious adverse events. Being a first-in-humans trial, our single-

hort 2, and 1 from cohort 3) were followed up at 3 months with center, open-label phase 1 study was designed to determine

VAS, SNOT-22, and LKS assessments. A continuing trend to- the safety and tolerability of ascending concentrations of phage

ward further improvement in all outcome measures was noted. AB-SA01 delivered as an intranasal rinse. Patients selected for

Mean difference in VAS was −3.67 (SD), in SNOT-22 was −5.25 this phase 1 study had failed all other conventional medical

(SD), and in LKS was −1 (SD), in which positive values indicate therapies and therefore served as their own controls. The re-

deterioration from pretreatment and negative values, improve- sults of our phase 1 study will guide a phase 2 trial in which a

ment from pretreatment. Results are shown in Figure 4. randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled group will be

used to evaluate efficacy.

Our safety result is consistent with the current body of lit-

erature with regard to phage use. Several phase 1 human clini-

Discussion cal trials have been conducted after application of phages topi-

This study indicated that twice-daily intranasal irrigations to cally (to the skin) or orally, with no serious adverse events

3 × 109 PFU for 14 days were safe and well tolerated with no reported. In a placebo-controlled phase 1 study,23 42 patients

jamaotolaryngology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 E5

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis

tested the safety of phage mixes against S aure us, suspected anti-inflammatory effects of phages. In the con-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli for the treat- text of infection, phages have been reported to show anti-

ment of chronic venous leg ulcers. Patients were treated for inflammatory effects by reducing neutrophils and proinflam-

12 weeks and followed up to 24 weeks with no reported sig- matory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 and interleukin 1β,30,31

nificant adverse effects. Another phase 1 study24 applied a and by reducing reactive oxygen species production.32

single-spray phage cocktail active against P aeruginosa and The paradoxical worsening of VAS scores observed in co-

S aureus on colonized burn wounds in 9 patients. No adverse hort 2 wherein 2 of 3 patients had eradication of bacteria is

events, clinical abnormalities, or changes in laboratory re- primarily due to a single patient (eFigure in Supplement 1).

sults were observed. The first modern, double-blinded, Patients 2 and 3 with eradication of bacteria showed consis-

controlled clinical trial25 using phages to treat refractory tent improvement across VAS, SNOT-22, and LKS assess-

P aeruginosa ear infections was conducted in England in ments. The reason for patient 1’s seemingly paradoxical re-

2007. Twenty-four patients were randomized to receive a single sult is unclear. Inflammation after bacterial lysis and endotoxin

dose of phage or placebo, and both groups were monitored for release33 has been a postulated adverse effect, although sev-

42 days. Pseudomonas aeruginosa counts were lower for the eral studies of phage therapy in humans34,35 and animals36,37

phage-treated group, with no reported adverse events. did not report any evidence of such responses.

The safety of phage treatment has also been recorded in Interestingly, continued clinical observations of certain pa-

healthy adults after oral administration. A pilot study26 tested tients beyond the formal duration of the trial showed a pos-

the safety of a coliphage in 15 healthy adult volunteers. Two sible sustained clinical effect to 3 months after phage treat-

different doses of the T4 coliphage (103 and 105 PFU/mL) were ment. This finding may be due to the persistence and

mixed with drinking water. The counts of normal E coli flora prophylactic potential of phages, which was not assayed.

did not decrease, and no adverse events were reported. In a Future clinical studies may benefit from longer follow-up.

follow-up study,27 15 healthy adults received a phage cocktail Previous in vivo studies 14 have identified low levels of

composed of 9 E coli phages at 2 different concentrations to active phages still present within sinuses 24 hours after ad-

3 × 109 PFU. The results showed no adverse events by self- ministration, consistent with various other studies showing

report or clinical examination. The laboratory tests for liver, serum phage persistence from 48 hours to 38 days after

kidney, and hematology function were also reported as within inoculation,38,39 with clearance of phages by the reticuloen-

reference limits. Importantly, oral phage treatment had no dothelial system.40 The intranasal administration of phages

effect on the fecal microbiota composition. in the sinuses may prolong phage persistence by bypassing

Phage preparations administered to humans with CRS have the reticuloendothelial system, especially in the presence

been reported previously,28,29 with favorable outcomes of ap- of remaining bacterial cells, which would enable self-

proximately 78% to 83% efficacy in infection control and no replication. Wright et al25 reported 200-fold amplification of

significant adverse effects. Mills28 administered α-lysate with P aeruginosa phages more than 42 days after a single dose of

occasional β-lysate staphylococcus bacteriophages via a nebu- treatment. Multiple studies have also suggested phages may

lizer for individualized durations followed by monthly main- play a protective role and assist in bacterial clearance when

tenance doses. Weber-Dabrowska et al29 administered phages subsequent infection is encountered.31,38,39

orally and topically from repeated antral punctures for 4 to 12

weeks. However, the overall interpretation of the aggregate

data is limited by the absence of preestablished safety and ef-

ficacy end points and information on concomitant antimicro-

Conclusions

bial therapies. The AB-SA01 phage cocktail for intranasal irrigation appears

to be safe and well tolerated to 3 × 109 PFU for 14 days with

Limitations no dose-limiting adverse effects. The preliminary efficacy data

We are only able to comment on the trends observed in this suggest that prolonged antimicrobial effects are possible,

study. The preliminary efficacy observations are promising. Al- allowing for a more targeted approach in treating recalcitrant

though no clinically meaningful changes occurred in the vali- sinus infections and associated inflammation due to

dated symptom scores relevant to sinus disease (VAS and S aureus. Further work must be performed to determine the

SNOT-22 scores), the clinical improvements seen endoscopi- optimal dose regimen and demonstrate the efficacy of

cally may be explained by a reduction in bacterial load and the AB-SA01 in a statistically powered randomized clinical trial.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Concept and design: Ooi, Drilling, Morales, Vreugde, Obtained funding: Drilling, Vreugde, Psaltis,

Accepted for Publication: April 11, 2019. Psaltis, Wormald. Wormald.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Ooi, Administrative, technical, or material support: Ooi,

Published Online: June 20, 2019. Morales, Fong, Moraitis, Macias-Valle, Vreugde, Drilling, Morales, Fong, Moraitis, Vreugde,

doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1191 Psaltis, Wormald. Wormald.

Author Contributions: Dr Wormald had full access Drafting of the manuscript: Ooi, Vreugde. Supervision: Drilling, Morales, Macias-Valle,

to all the data in the study and takes responsibility Critical revision of the manuscript for important Vreugde, Psaltis, Wormald.

for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the intellectual content: Ooi, Drilling, Morales, Fong, Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Morales

data analysis. Moraitis, Macias-Valle, Vreugde, Wormald. reported being employed by AmpliPhi Biosciences

Corporation. No other disclosures were reported.

E6 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 (Reprinted) jamaotolaryngology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Safety and Tolerability of Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Chronic Rhinosinusitis Original Investigation Research

Funding/Support: This study was supported in 12. Asavarut P, Hajitou A. The phage revolution 26. Bruttin A, Brüssow H. Human volunteers

part (70%) by the Department of Otolaryngology– against antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 orally: a safety

Head and Neck Surgery, University of Adelaide and 2014;14(8):686. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14) test of phage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

in part (30%) by AmpliPhi Biosciences Corporation 70867-9 2005;49(7):2874-2878. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.7.2874-

(Ms Moraitis). 13. Lehman SM, Mearns G, Rankin D, et al. Design 2878.2005

Role of Funder/Sponsor: The sponsors had no role and preclinical development of a phage product for 27. Sarker SA, McCallin S, Barretto C, et al. Oral

in the design and conduct of the study; collection, the treatment of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus T4-like phage cocktail application to healthy adult

management, analysis, and interpretation of data; aureus infections. Viruses. 2019;11(1):88. doi:10. volunteers from Bangladesh. Virology. 2012;434(2):

3390/v11010088 222-232. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.002

preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript;

and decision to submit the manuscript for 14. Drilling A, Morales S, Boase S, et al. Safety and 28. Mills AE. Staphylococcus bacteriophage lysate

publication. efficacy of topical bacteriophage and aerosol therapy of sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1956;66

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid treatment of (7):846-858. doi:10.1288/00005537-195607000-

Additional Contributions: Peter Speck, Staphylococcus aureus infection in a sheep model of 00004

BSc (Hons), PhD, Biological Sciences, Adelaide, sinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(3):176-186.

Australia, introduced phage therapy to our 29. Weber-Dabrowska B, Mulczyk M, Górski A.

doi:10.1002/alr.21270 Bacteriophage therapy of bacterial infections: an

department and provided expertise on previous

15. Drilling AJ, Ooi ML, Miljkovic D, et al. Long-term update of our institute’s experience. Arch Immunol

phage studies. Eric Gowans, MAppSc, PhD,

safety of topical bacteriophage application to the Ther Exp (Warsz). 2000;48(6):547-551.

Department of Virology and Vaccine Development,

frontal sinus region. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017; 30. Wang Z, Zheng P, Ji W, et al. SLPW: a virulent

Basil Hetzel Institute for Translational Health 7:49. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2017.00049

Research, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, bacteriophage targeting methicillin-resistant

Australia, participated as our virology expert on our 16. Mizoguchi K, Morita M, Fischer CR, Yoichi M, Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo. Front

Tanji Y, Unno H. Coevolution of bacteriophage PP01 Microbiol. 2016;7:934. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.

safety monitoring committee. Neither individual

and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in continuous culture. 00934

received compensation for contributions to

Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(1):170-176. doi:10. 31. Pabary R, Singh C, Morales S, et al.

this project.

1128/AEM.69.1.170-176.2003 Antipseudomonal bacteriophage reduces infective

REFERENCES 17. Nale JY, Spencer J, Hargreaves KR, et al. burden and inflammatory response in murine lung.

Bacteriophage combinations significantly reduce Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60(2):744-751.

1. Foreman A, Jervis-Bardy J, Wormald P-J. Do Clostridium difficile growth in vitro and proliferation doi:10.1128/AAC.01426-15

biofilms contribute to the initiation and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60(2):

recalcitrance of chronic rhinosinusitis? Laryngoscope. 32. Miedzybrodzki R, Switala-Jelen K, Fortuna W,

968-981. doi:10.1128/AAC.01774-15 et al. Bacteriophage preparation inhibition of

2011;121(5):1085-1091. doi:10.1002/lary.21438

18. Drilling A, Morales S, Jardeleza C, Vreugde S, reactive oxygen species generation by

2. Foreman A, Psaltis AJ, Tan LW, Wormald PJ. Speck P, Wormald PJ. Bacteriophage reduces endotoxin-stimulated polymorphonuclear

Characterization of bacterial and fungal biofilms in biofilm of Staphylococcus aureus ex vivo isolates leukocytes. Virus Res. 2008;131(2):233-242. doi:10.

chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23 from chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Am J Rhinol 1016/j.virusres.2007.09.013

(6):556-561. doi:10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3413 Allergy. 2014;28(1):3-11. doi:10.2500/ajra.2014.28. 33. Pound MW, May DB. Proposed mechanisms

3. Zhang G, Zhao Y, Paramasivan S, et al. 4001 and preventative options of Jarisch-Herxheimer

Bacteriophage effectively kills multidrug resistant 19. Kennedy JL, Hubbard MA, Huyett P, Patrie JT, reactions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30(3):291-295.

Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates from chronic Borish L, Payne SC. Sino-Nasal Outcome Test doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00631.x

rhinosinusitis patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. (SNOT-22): a predictor of postsurgical improvement

2018;8(3):406-414. doi:10.1002/alr.22046 34. Sulakvelidze AKE. Bacteriophage Therapy in

in patients with chronic sinusitis. Ann Allergy Humans. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005.

4. Guttman B, Raya R, Kutter E. Basic phage Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(4):246-251.e2. doi:10.

biology. In: Kutter E, Sulakvelidze A, eds. 1016/j.anai.2013.06.033 35. Sarker SA, Sultana S, Reuteler G, et al. Oral

Bacteriophages, Biology and Applications. Boca Raton, phage therapy of acute bacterial diarrhea with two

20. Walker FD, White PS. Sinus symptom scores: coliphage preparations: a randomized trial in

LA: CRC Press; 2004:29-66. doi:10.1201/ what is the range in healthy individuals? Clin

9780203491751.ch3 children from Bangladesh. EBioMedicine. 2016;4:

Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25(6):482-484. doi:10. 124-137. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.12.023

5. Clokie MR, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. 1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00349.x

Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(1):31-45. 36. Soothill J, Hawkins C, Anggård E, Harper D.

21. Lund VJ, Kennedy DW; The Staging and Therapy Therapeutic use of bacteriophages. Lancet Infect Dis.

doi:10.4161/bact.1.1.14942 Group. Quantification for staging sinusitis. Ann Otol 2004;4(9):544-545. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)

6. Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG Jr. Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1995;167:17-21. doi:10.1177/ 01127-2

Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents 000348949510410s02

Chemother. 2001;45(3):649-659. doi:10.1128/AAC. 37. Golkar Z, Bagasra O, Jamil N. Experimental

22. Chowdhury NI, Mace JC, Bodner TE, et al. phage therapy on multiple drug resistant

45.3.649-659.2001 Investigating the minimal clinically important Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice. J Antivir

7. Carlton RM. Phage therapy: past history and difference for SNOT-22 symptom domains in Antiretrovir. 2013;S10:005. doi:10.4172/jaa.S10-005

future prospects. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). surgically managed chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum

1999;47(5):267-274. Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(12):1149-1155. doi:10.1002/ 38. Capparelli R, Parlato M, Borriello G, Salvatore P,

alr.22028 Iannelli D. Experimental phage therapy against

8. Loc-Carrillo C, Abedon ST. Pros and cons of Staphylococcus aureus in mice. Antimicrob Agents

phage therapy. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):111-114. doi: 23. Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Kuskowski MA, Chemother. 2007;51(8):2765-2773. doi:10.1128/

10.4161/bact.1.2.14590 Wolcott BM, Ward LS, Sulakvelidze A. AAC.01513-06

9. Harper DR, Parracho HMRT, Walker J, et al. Bacteriophage therapy of venous leg ulcers in

humans: results of a phase I safety trial. J Wound Care. 39. Chhibber S, Kaur S, Kumari S. Therapeutic

Bacteriophages and biofilms. Antibiotics (Basel). potential of bacteriophage in treating Klebsiella

2014;3(3):270-284. doi:10.3390/antibiotics3030270 2009;18(6):237-238, 240-243. doi:10.12968/jowc.

2009.18.6.42801 pneumoniae B5055-mediated lobar pneumonia in

10. Römling U, Balsalobre C. Biofilm infections, mice. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(pt 12):1508-1513.

their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment 24. Rose T, Verbeken G, Vos DD, et al. Experimental doi:10.1099/jmm.0.2008/002873-0

strategies. J Intern Med. 2012;272(6):541-561. doi: phage therapy of burn wound infection: difficult

first steps. Int J Burns Trauma. 2014;4(2):66-73. 40. Westwater C, Kasman LM, Schofield DA, et al.

10.1111/joim.12004 Use of genetically engineered phage to deliver

11. Chan BK, Sistrom M, Wertz JE, Kortright KE, 25. Wright A, Hawkins CH, Anggård EE, Harper DR. antimicrobial agents to bacteria: an alternative

A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic therapy for treatment of bacterial infections.

Narayan D, Turner PE. Phage selection restores

bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(4):1301-1307.

antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas

antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: doi:10.1128/AAC.47.4.1301-1307.2003

aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26717. doi:10.1038/

a preliminary report of efficacy. Clin Otolaryngol.

srep26717

2009;34(4):349-357. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.

01973.x

jamaotolaryngology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Published online June 20, 2019 E7

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Anatomy and Physiology of FeedingDocumento17 pagineAnatomy and Physiology of Feedingopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Midline Granuloma Diagnosis and Management ChallengesDocumento13 pagineMidline Granuloma Diagnosis and Management Challengesopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatomy and Its Variations For Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10013-1122Documento8 pagineAnatomy and Its Variations For Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10013-1122opi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Ear: Mlddle inDocumento4 pagineChronic Ear: Mlddle inopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Article: Chronic Rhinosinusitis in ChildrenDocumento6 pagineReview Article: Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Childrenopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Cholesteatoma - Diagnosing The Unsafe EarDocumento6 pagineCholesteatoma - Diagnosing The Unsafe EarGuillermo StipechNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis in ChildrenDocumento11 pagineChronic Rhinosinusitis in Childrenopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatomy and Physiology of FeedingDocumento17 pagineAnatomy and Physiology of Feedingopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Lethal Midline Granuloma-Stewart Nasal Nk/T-Cell Lymphoma-0ur ExperienceDocumento9 pagineLethal Midline Granuloma-Stewart Nasal Nk/T-Cell Lymphoma-0ur Experienceopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Lethal Midline Granuloma-Stewart Nasal Nk/T-Cell Lymphoma-0ur ExperienceDocumento9 pagineLethal Midline Granuloma-Stewart Nasal Nk/T-Cell Lymphoma-0ur Experienceopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Ear: Mlddle inDocumento4 pagineChronic Ear: Mlddle inopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Palatal SwellingsDocumento6 paginePalatal Swellingsopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Konsep Dasar LukaDocumento7 pagineKonsep Dasar Lukaopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- AJCC Cancer Staging Form Supplement PDFDocumento520 pagineAJCC Cancer Staging Form Supplement PDFopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Sleep Performance The WorkplaceDocumento42 pagineSleep Performance The Workplaceopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Hsg256 - Managing ShiftworkDocumento45 pagineHsg256 - Managing ShiftworkeustaquipaixaoNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Manage Shiftwork Guide 0224Documento12 pagineHow To Manage Shiftwork Guide 0224opi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- VIVA Training in ENTDocumento5 pagineVIVA Training in ENTopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Offshore Working Tiem in Relation To Performance, Health PDFDocumento80 pagineOffshore Working Tiem in Relation To Performance, Health PDFopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Sleep Tips For Employers and Shift Workers PDFDocumento2 pagineSleep Tips For Employers and Shift Workers PDFopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress Awareness at Workplace in Develoving CountryDocumento49 pagineStress Awareness at Workplace in Develoving Countryopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Circadian Rhythms and Shift Work 2010 VTDocumento94 pagineCircadian Rhythms and Shift Work 2010 VTopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Pcs 2018 PDFDocumento1.876 paginePcs 2018 PDFopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Work Schedules in Oilfield IndustryDocumento10 pagineWork Schedules in Oilfield Industryopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress 6Documento4 pagineStress 6purneshwariNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Indeks Glikemik MakananDocumento10 pagineDaftar Indeks Glikemik Makananopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Avisory Leaflet Managing Stress in The Workplace PDFDocumento12 pagineAvisory Leaflet Managing Stress in The Workplace PDFJe Paderan TorilloNessuna valutazione finora

- OHAG - Fitness To Work at HeightsDocumento4 pagineOHAG - Fitness To Work at Heightsopi akbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Fitness To Work Offshore GuidelineDocumento28 pagineFitness To Work Offshore GuidelineMohd Zaha Hisham100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Noscapine - British PharmacopoeiaDocumento3 pagineNoscapine - British PharmacopoeiaSocial Service (V)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Physiology of Cerebellum Lec Foe 2nd Year by DR Sadia Uploaded by ZaighamDocumento61 paginePhysiology of Cerebellum Lec Foe 2nd Year by DR Sadia Uploaded by ZaighamZaigham HammadNessuna valutazione finora

- Sickle Cell AnemiaDocumento7 pagineSickle Cell AnemiaJuma AwarNessuna valutazione finora

- Short Periods of Incubation During Egg Storage - SPIDESDocumento11 pagineShort Periods of Incubation During Egg Storage - SPIDESPravin SamyNessuna valutazione finora

- HHS Public Access: Structure and Function of The Human Skin MicrobiomeDocumento20 pagineHHS Public Access: Structure and Function of The Human Skin MicrobiomeEugeniaNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Techno: Cbse Class-Ix - E6 - E-Techno JEE TEST DATE: 17-11-2020Documento16 pagineE-Techno: Cbse Class-Ix - E6 - E-Techno JEE TEST DATE: 17-11-2020Himanshu ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- Book of Mythical BeastsDocumento32 pagineBook of Mythical BeastsRishabhNessuna valutazione finora

- Natamycin Story - What You Need to KnowDocumento13 pagineNatamycin Story - What You Need to KnowCharles MardiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Sleep Deprivation among Students in Saint Francis of Assisi CollegeDocumento50 pagineEffects of Sleep Deprivation among Students in Saint Francis of Assisi College• Cielo •Nessuna valutazione finora

- RT-PCR Kit for RNA Detection up to 6.5kbDocumento14 pagineRT-PCR Kit for RNA Detection up to 6.5kbLatifa Putri FajrNessuna valutazione finora

- Field Inspection Techniques Ifad-CaspDocumento17 pagineField Inspection Techniques Ifad-CaspNasiru Kura100% (1)

- Candida Tropicalis - ACMGDocumento12 pagineCandida Tropicalis - ACMGSergio Iván López LallanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 Cell - The Unit of Life-NotesDocumento6 pagine8 Cell - The Unit of Life-NotesBhavanya RavichandrenNessuna valutazione finora

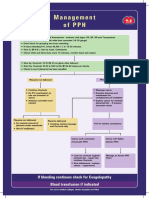

- Management of PPHDocumento1 paginaManagement of PPH098 U.KARTHIK SARAVANA KANTHNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Lab ReportDocumento7 pagineSample Lab ReportPutri Syalieyana0% (1)

- Since 1938 We Are Upholding The Spirit That Founded Our University and Encourage Each Other To ExploreDocumento71 pagineSince 1938 We Are Upholding The Spirit That Founded Our University and Encourage Each Other To ExploreShohel RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 皮膚病介紹Documento93 pagine皮膚病介紹MK CameraNessuna valutazione finora

- Transport Phenomena in Nervous System PDFDocumento538 pagineTransport Phenomena in Nervous System PDFUdayanidhi RNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-symbiotic Nitrogen FixersDocumento21 pagineNon-symbiotic Nitrogen Fixersrajiv pathakNessuna valutazione finora

- Citric Acid Production Stirred TankDocumento9 pagineCitric Acid Production Stirred TankKarliiux MedinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Explaining Butterfly MetamorphosisDocumento13 pagineExplaining Butterfly MetamorphosisCipe drNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Dimensions of Late Pleistocene/Holocene Arid Events in Southern South AmericaDocumento13 pagineHuman Dimensions of Late Pleistocene/Holocene Arid Events in Southern South AmericaKaren RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- (PDF) Root Growth of Phalsa (Grewia Asiatica L.) As Affected by Type of CuttDocumento5 pagine(PDF) Root Growth of Phalsa (Grewia Asiatica L.) As Affected by Type of CuttAliNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Qualitative Tests (Pharmacognosy)Documento8 pagineSummary of Qualitative Tests (Pharmacognosy)kidsaintfineNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Harvest Handling in LitchiDocumento52 paginePost Harvest Handling in LitchiDr Parag B JadhavNessuna valutazione finora

- TC QMM 56942Documento120 pagineTC QMM 56942Fernando R EpilNessuna valutazione finora

- The Vulcanization of BrainDocumento30 pagineThe Vulcanization of BrainJohnny FragosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chiro Guidelines WHODocumento51 pagineChiro Guidelines WHOMinh MinhNessuna valutazione finora

- LWT - Food Science and TechnologyDocumento8 pagineLWT - Food Science and TechnologyAzb 711Nessuna valutazione finora

- PRACTICE TEST - Gen - EdDocumento93 paginePRACTICE TEST - Gen - EddispacitoteamoNessuna valutazione finora