Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Teroris Si Extremism de Dreapta 2

Caricato da

Web AdevarulCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Teroris Si Extremism de Dreapta 2

Caricato da

Web AdevarulCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Council of the

European Union

Brussels, 30 August 2019

(OR. en)

11756/19

ADD 1

LIMITE

CT 81

ENFOPOL 375

COTER 112

JAI 876

NOTE

From: EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator

To: Delegations

Subject: Right-wing violent extremism and terrorism in the European Union:

background information

1. Definition of right-wing extremist terrorism and European statistics

The distinction between other right-wing extremist violence and right-wing terrorism is based on

the EU CT directive1. The Commission will report on the transposition to Council and the European

Parliament in March 2020. The Directive is based on the understanding that terrorism is politically

neutral. In the Directive terrorism is clearly defined by requiring two cumulative elements: one part

consists of the seriousness of offences and the other part the terrorist aim with which these are

committed. When one or the other element is missing, it is not considered terrorism. From a strictly

legal point of view, this is a clear line. The Directive defines as criminal offenses preparatory acts

such as provocation to commit terrorism, training for terrorism that may be easier to prove and that

can be used at an earlier stage to start investigations and prosecutions for individual actors in “fluid”

or “hard to prove” violent extremist groups. This could make it easier for Member States to

prosecute right-wing violent extremism and terrorism.

1

Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on combating

terrorism and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA (OJ L 88, 31.3.2017, p. 6).

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 1

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

Often, right-wing violent extremist crimes are prosecuted under other criminal statutes in Member

States (e.g. causing an explosion, possession of illicit-arms, attempted murder) and receive adequate

sentences. Right-wing extremist violence can fall under the wide scope of non-terrorist violent

crimes, including hate crimes. Such offenses are often the beginning of further violent extremist

radicalization. Verbal attacks, also online, can lower the threshold for the real use of violence.

Contrary to terrorist offenses, statistics on other right-wing extremist violence are not systematically

collected at EU level2 and hence not available in a comparable fashion3.

Terrorism-related arrests and prosecutions as well as the number and nature of terrorist incidents in

Member States are being published annually by Europol in the TE-SAT report4. It also provides

some qualitative information on right-wing violent extremism. However, the report does not include

incidents that are prosecuted under other criminal statutes5. Current reporting procedures have been

shaped by the experience with jihadist terrorism and are not necessarily adequate to cover violent

incidents motivated by right-wing violent extremism that cannot be classified as terrorism.

A project that has tried to explore possible ways to collect data in this field is the ISF-funded

“Politically motivated crime in the light of current migration flows” (PoMigra) project, which

aimed to shed light on the possible correlation between the influx of migrants in the EU and

extremist crimes. Difficulties emerged in collecting statistical data in Member States, and at present

data sets at the national level are not comparable. As a result, evidence-based advice for policy

making at European level can be challenging.

2

The EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) and the Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of

the OSCE (ODHIR) are providing some statistics on specific aspects of right-wing violent extremism and

terrorism. However, often the statistics provided by the Member States are difficult to compare.

3

The 2018 Report of the German security service (BfV) for example contains statistics at the national level.

It counted some 12,700 "violence-oriented" right-wing extremists in Germany. While the overall number of

right-wing crimes dropped by 0.3% in 2018, the number of violent crimes committed by right-wing

extremists rose by 3.2% (from 1,054 to 1,088).

4

Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2019 (TE-SAT), Europol, p. 72

(https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/main-reports/terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2019-

te-sat).

5

This would raise methodological problems: It seems difficult to classify cases for which insufficient

evidence exists to secure terrorism or violent extremism convictions as terrorism or violent extremism for

statistical purposes.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 2

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

2. Europol and Eurojust

Europol provided operational support in the aftermath of the Christchurch attack as well as in other

cases of right-wing extremist terrorism. It coordinated efforts and information exchange among

Member States and New Zealand6. For this reason, Europol also activated the exceptional clause7.

Three operational analysis reports were drafted by the European Counter-Terrorism Centre (ECTC)

and shared with Member States and New Zealand.

The Analysis Project (AP) Dolphin (for non-Islamist terrorism) has among its priorities the fight

against right-wing violent extremism and terrorism and is supporting ongoing priority cases

investigated by Member States.

Since 2017, Europol has started to provide dedicated support to major special events in Member

States, for example with cross-checking of photos, images and videos as well as intelligence

reports. This targets all threats and hence could also be used in the context of right-wing violent

extremism and terrorism.

Additional effort in the fight against right-wing violent extremism and terrorism by the EU Internet

Referral Unit (IRU) would be possible since Europol's mandate already allows the agency to

"prevent and combat forms of crime [including terrorism and racism and xenophobia], which are

facilitated, promoted or committed using the Internet."

Neither the national IRUs nor the EU IRU work systematically on the detection and referral of anti-

Semitic content or unlawful hate speech in general8. Some investigations units in Member States

(not necessarily IRU) work on this issue on an ad hoc basis in the framework of open

investigations9. Being driven and directed by the demands of the Member States, the ECTC and in

particular the EU IRU operational support has been predominantly focused on jihadist terrorism.

However, right-wing violent extremism and terrorism already has raised and most probably will

continue to raise demands and increase expectations on the ECTC support to the Member States in

this field.

6

Via the Australian desk at Europol

7

Art. 25(5) of the Europol Regulation (on authorisation of transfer of personal data to third countries and

international organizations)

8

Anti-Semitic content online / unlawful hate speech and the role of the EU IRU and national IRUs was

discussed during the last Heads of IRU meeting in early June 2019.

9

Cases filed by individuals.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 3

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

The ECTC is proactively engaging with and encouraging Member States to increase and standardise

reporting on right-wing extremist violence and right-wing terrorism, also to allow to

comprehensively and representatively assess the situation in the EU on this phenomenon10.

Eurojust discussed prosecutions of right-wing extremist terrorism at its annual CT meeting in June

2019. Eurojust also supports judicial cooperation in right-wing violent extremism and terrorism

cases. In October 2018 Eurojust was invited to join Europol's AP Dolphin, which ensures more

structured cooperation with the AP to which Eurojust already contributed even prior to the

association. Eurojust provides analysis of terrorist related judgments in Member States, including

related to right-wing extremist terrorism in its Terrorist Convictions Monitor. Information exchange

on judicial investigations and prosecutions of terrorism, including right-wing extremist terrorism,

will be strengthened with the launch of the European Judicial CT Register in September 2019.

3. Disengagement programmes

It is important for Member States to build and share experience with regard to disengagement

programmes. The German experience with neo-Nazis seems to be very interesting, keeping in mind

that right-wing violent extremism and terrorism has evolved over the last years and has different

shapes and structures across Member States. In the exit program in Finland, there are customers

with radical jihadist ideology as well as right-wing violent extremists. It would be useful to know

whether exit programs in Member States are available only to radicalized persons with a certain

ideology or open to all radicalized persons no matter what is the ideology they follow.

4. Possible interaction between jihadist and right-wing violent extremist ideologies

It is important to understand and address the ideological dimension of right-wing violent extremism

which can contribute to radicalization to right-wing terrorism.

10

Europol will report to TWP in September 2019, as requested, and in the bi-annual six-monthly threat

assessment (scope extended beyond jihadist extremism as agreed at the Council's Standing Committee on

Operational Cooperation on Internal Security (COSI) meeting in May 2019).

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 4

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

In this context, it is interesting to note that while jihadist ideology and right-wing violent extremist

ideology fundamentally clash with each other, at the same time the jihadist and right-wing violent

extremist ideologies have some common features. The common tenets include supremacist

ideology, hatred of the other, the perception of own communities being under threat, or belief in

clash of civilisations and considering the use of violence. Moreover, both jihadist and right-wing

violent extremist ideologies can be anti-Semitic, misogynist, homophobic and xenophobic. Both

claim that Muslims cannot be integrated in the West nor be reconciled with the West. Both refuse

the basic principles of Western democracies. It would be interesting to examine similarities with

left-wing violent extremist ideology as well.

However, this does not necessarily mean that the same indicators for risk analysis with regard to

the threat posed by jihadist radicalized persons can be used with regard to radicalized right-wing

violent extremist persons. For example, in Germany the Radar ITE11 indicators are not used in the

context of right-wing terrorism.

There may be an interlink between an attack claimed by a Jihadist terrorist group and a subsequent

increase in anti-Muslim incidents. Reversely, right-wing extremist terrorist attacks and other right-

wing extremist violence might be met by retaliation from jihadist groups, or cause an increase in

jihadist recruitment among people affected by a given incident. It remains open to what extent this

correlation is indeed observable. There is also a threat of reciprocal violence between right-wing

violent extremist groups and those opposed to them, which may lead to further radicalization of

both sides. For example, there have been violent clashes between right-wing violent extremists and

Salafists in Germany12. In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in 2015, incidents of right-

wing extremist violence against Muslims rose by 281 % in France13. The "Terrorist Threat

Assessment for the Netherlands 50"14 of June 2019 points out that "terrorist incidents can also

function as a trigger for violent retaliation by jihadists or right-wing extremists".

11

The risk assessment tool of the German Federal Criminal Police (BKA) in the context of jihadist terrorism.

12

Koehler, Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism in Europe, Current Developments and issues for the

future, PRISM 6, No. 2 pp. 92

13

Koehler

14

https://english.nctv.nl/binaries/Samenvatting%20DTN50%20EN_tcm32-396781.pdf, June 2019.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 5

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

5. Right-wing violent extremism and terrorism online

The internet and social media play an important role regarding the spread of right-wing violent

extremist and terrorist content. The internet is one of the key enablers of violent radicalisation and

formation of groups, including those consisting of right-wing violent extremist sympathisers who

search for ideological validation online. Participation in online right-wing violent extremist fora can

act as a "tasting ground" and motor for offline violence.

While jihadist content is dominated by a small number of groups such as Daesh or Al-Qaeda which

produce the overwhelming majority of online content, right-wing violent extremist content

emanates from multiple sources15 and thus has multiple narratives, goals and targets. This poses a

potential challenge for detection of unlawful right-wing violent extremist and terrorist materials.

Big data analytics on violent right-wing extremist content online seems to be missing.

Right-wing extremist content online can be divided into three categories: lawful content under free

speech laws, unlawful hate speech (or other unlawful symbols, for example those that have been

banned), and terrorist content. It is a challenge that context is often necessary to identify the right-

wing violent extremist symbols. Only terrorist and other unlawful content can be removed.

Several Member States have banned some right-wing violent extremist symbols and expressions.

However, these symbols and expressions tend to change and adapt, depending on national

measures. The fact that national bans do not cover the whole of the EU might create a challenge for

removal requests, as social media are operating internationally.

The EU Directive 2017/541 on combating terrorism tasked Member States to inter alia take

necessary measures against the spread of terrorist content online. The EU Internet Forum,

established in 2015 by the European Commission deals with terrorist content, hence it could also

tackle right-wing violent extremist and terrorist content.

15

Maura Conway, "Violent Extremism and Terrorism," VoxPol, 2018, https://voxpol.eu/download/vox-

pol_publication/Year-in-Review-2018.pdf, p. 12.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 6

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

The European Commission Code of Conduct countering illegal speech online from 201616 and the

relevant dialogue with the internet companies covers unlawful hate speech, hence right-wing

extremist content that is not terrorist content but constitutes unlawful hate speech. The

Commission's Code of Conduct is a legally non-binding agreement. It commits companies which

are parties to the document to have a clear and effective review process concerning illegal hate

speech online, defined as "all conduct publicly inciting to violence or hatred directed against a

group of persons or a member of such a group defined by reference to race, colour religion, descent

or national or ethnic origin."17 Yet this work remains voluntary and the EU has no legal mechanism

holding IT companies responsible for hosting illegal hate speech. The EU supports a network of

flaggers to support the hate speech dialogue.

As a consequence of the attacks in Christchurch, French President Macron and New Zealand Prime

Minister Ardern brought together Heads of State and Government and leaders from the tech sector

to adopt the Christchurch Call18, a commitment by Governments and tech companies to eliminate

terrorist and violent extremist content online. It rests on the conviction that a free, open and secure

internet offers extraordinary benefits to society. Respect for freedom of expression is fundamental.

However, no one has the right to create and share terrorist and violent extremist content online.

Also in this context, the EU Internet Forum members agreed to work together to establish a

blueprint for a crisis protocol in full compliance with human rights and data protection standards

which will be presented by the Commission in a few months. The protocol will apply to situations

where there is a terrorist attack with a significant online component19.

16

https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/racism-and-

xenophobia/countering-illegal-hate-speech-online_en#relatedlinks

17

https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/racism-and-

xenophobia/countering-illegal-hate-speech-online_en

18

Meeting in Paris on 15 May 2019; https://www.christchurchcall.com.

19

For this, single points of contacts for alerting each other would be set up as well as pre-defined

communication channels for real time coordination during the crisis both between industry and between

industry, Europol and law enforcement.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 7

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

6. Traditional media

Traditional media are still playing an important role in communicating and presenting facts,

analyses and commentaries to its audience. Moreover, traditional media are often a source for social

media. After significant violent or terrorist incidents, reporting via mass media channels may

contribute to acceleration of polarisation in the society. To prevent further alienating certain parts of

the society and fuelling radicalisation, initiatives raising awareness among traditional media (TV

channels, newspapers, radio etc.) and enhancing information management between public

authorities and media could be encouraged and supported by the Commission and Member States.

11756/19 ADD 1 GDK/is 8

GSC.CTC LIMITE EN

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Draft AusteritateDocumento59 pagineDraft AusteritateWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 States LetterDocumento4 pagine8 States LetterWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Anunt Ecs Imobile 114Documento2 pagineAnunt Ecs Imobile 114Web AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- COM 2022 586 1 EN ACT Part1 v8Documento66 pagineCOM 2022 586 1 EN ACT Part1 v8Web AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Mr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUDocumento2 pagineMr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Executive Summary 2022 6 Inf ROMANIANDocumento4 pagineExecutive Summary 2022 6 Inf ROMANIANWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Declaration enDocumento2 pagineDeclaration enWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Us AirforceDocumento71 pagineUs AirforceWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Bucharest Conference - ProgrammeDocumento4 pagineBucharest Conference - ProgrammeWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- PCT 14Documento2 paginePCT 14Web AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Mr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUDocumento2 pagineMr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Mr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUDocumento2 pagineMr. Nikos CHARDALIAS Mr. Vasileios PAPAGEORGIOUWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- CPT/Inf (2022) 06: Under Embargo Until 14 April 2022 at 10.00 Am CESTDocumento68 pagineCPT/Inf (2022) 06: Under Embargo Until 14 April 2022 at 10.00 Am CESTWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- NATO Expansion - What Gorbachev Heard - National Security ArchiveDocumento40 pagineNATO Expansion - What Gorbachev Heard - National Security ArchiveWeb Adevarul100% (1)

- CPT - Romania ReportDocumento2 pagineCPT - Romania ReportWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaccines Contract Between European Commission and AstraZeneca Now PublishedDocumento1 paginaVaccines Contract Between European Commission and AstraZeneca Now PublishedWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Capitol Assault FBI DocumentDocumento16 pagineCapitol Assault FBI DocumentWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Left Wing ExtremismDocumento10 pagineLeft Wing ExtremismWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- El ChapoDocumento13 pagineEl ChapoWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Articles of ImpeachmentDocumento4 pagineArticles of Impeachmentacohnthehill86% (7)

- Affidavit FBIDocumento24 pagineAffidavit FBIWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

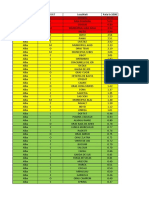

- RatainfectarepelocalitatiDocumento64 pagineRatainfectarepelocalitatiMediafax.ro100% (3)

- Articles of ImpeachmentDocumento4 pagineArticles of Impeachmentacohnthehill86% (7)

- ECFR Sondaj AmericaDocumento22 pagineECFR Sondaj AmericaMihai EpureNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 13112020 Ap enDocumento1 pagina2 13112020 Ap enWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- 2day Ambasador 2020 - Agenda Conferinta - Sesiunea 1 - 23 Nov 2020Documento5 pagine2day Ambasador 2020 - Agenda Conferinta - Sesiunea 1 - 23 Nov 2020Web AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- FDA LetterDocumento44 pagineFDA LetterWeb Adevarul75% (4)

- Prospectul Din Marea Britanie Al Vaccinului Pfizer Anti-CoronavirusDocumento5 pagineProspectul Din Marea Britanie Al Vaccinului Pfizer Anti-CoronavirusAndreea DogarNessuna valutazione finora

- Eu Council Draft Conclusion CONFIDENTIAL TerrorismDocumento7 pagineEu Council Draft Conclusion CONFIDENTIAL TerrorismWeb AdevarulNessuna valutazione finora

- Конституційний судDocumento2 pagineКонституційний судАнастасія ДячкінаNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Memorandum of AssociationDocumento6 pagineMemorandum of Associationshankha86100% (1)

- Silverio v. Republic, GR No. 174689 Oct. 22, 2007Documento6 pagineSilverio v. Republic, GR No. 174689 Oct. 22, 2007Ashley Kate PatalinjugNessuna valutazione finora

- Minutes: Motion Was Submitted For ResolutionDocumento26 pagineMinutes: Motion Was Submitted For ResolutionRonald ArvinNessuna valutazione finora

- Agbayani NegoDocumento276 pagineAgbayani NegoSharonRosanaEla100% (2)

- Essential Elements of A TaxDocumento3 pagineEssential Elements of A Taxcosmic lunacyNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Validity of The Minimum Wages ActDocumento19 pagineConstitutional Validity of The Minimum Wages Actinderpreet100% (2)

- Crim Book 2 CasesDocumento185 pagineCrim Book 2 CasesChard CaringalNessuna valutazione finora

- Certification of Non Forum ShoppingDocumento1 paginaCertification of Non Forum ShoppingAnonymous J6VnbpOiIvNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedom of Expression in PUVs and TerminalsDocumento4 pagineFreedom of Expression in PUVs and TerminalsEva TrinidadNessuna valutazione finora

- ObaShango-El's Template of Notice of Autochthonous StatusDocumento3 pagineObaShango-El's Template of Notice of Autochthonous StatusMikeDouglas100% (1)

- SC Affirms Will Admitting Wife as Heir Despite Relationship ClaimsDocumento4 pagineSC Affirms Will Admitting Wife as Heir Despite Relationship ClaimsRhyz Taruc-ConsorteNessuna valutazione finora

- Existence of A Clear Legal RightDocumento2 pagineExistence of A Clear Legal RightAprille S. AlviarneNessuna valutazione finora

- William Golangco Construction Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Commercial International Bank, Respondent DecisionDocumento18 pagineWilliam Golangco Construction Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Commercial International Bank, Respondent DecisionRyan MostarNessuna valutazione finora

- ANC ConstitutionDocumento20 pagineANC Constitutionanyak1167032Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lumayog V Pitcock - Prop EjectmentDocumento2 pagineLumayog V Pitcock - Prop EjectmentMichael Lamson Ortiz Luis0% (1)

- Office of The Provincial ProsecutorDocumento3 pagineOffice of The Provincial ProsecutorPj TignimanNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 167519. THE WELLEX GROUP, INC., Petitioner, vs. U-LAND AIRLINES, CO., LTD., RespondentDocumento77 pagineG.R. No. 167519. THE WELLEX GROUP, INC., Petitioner, vs. U-LAND AIRLINES, CO., LTD., RespondentMa. Christian RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Rules on Usufruct RightsDocumento4 pagineSupreme Court Rules on Usufruct RightsTEtchie TorreNessuna valutazione finora

- Dayot Vs ShellDocumento2 pagineDayot Vs ShellSachuzen23Nessuna valutazione finora

- Child Benefits FormDocumento9 pagineChild Benefits FormIoan-Daniel HustiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Goyanko Vs UCPB 690s79Documento9 pagineGoyanko Vs UCPB 690s79Norma Waban100% (1)

- United States v. Maling, 1st Cir. (1993)Documento26 pagineUnited States v. Maling, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Court lifts disbarment of lawyer after 3 yearsDocumento4 pagineCourt lifts disbarment of lawyer after 3 yearsMary Rose CaronNessuna valutazione finora

- Review PetitionDocumento19 pagineReview PetitionshwetaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v NiegasDocumento6 paginePeople v NiegasErwin L BernardinoNessuna valutazione finora

- People V BokingoDocumento2 paginePeople V Bokingoistefifay100% (2)

- Alcantara V. Reta, 372 Scra 364 - Personal Easement: FactsDocumento5 pagineAlcantara V. Reta, 372 Scra 364 - Personal Easement: FactsCj BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson III - Kant and Right TheoryDocumento25 pagineLesson III - Kant and Right TheoryPauline MoralNessuna valutazione finora

- ILEC Practice TestDocumento23 pagineILEC Practice TestTrâm Hoa Trương100% (2)

- A.C. Ransom Labor Union v. NLRCDocumento4 pagineA.C. Ransom Labor Union v. NLRCbearzhugNessuna valutazione finora