Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

007 - Kashmir's Accession To India (69-86)

Caricato da

soumyaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

007 - Kashmir's Accession To India (69-86)

Caricato da

soumyaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

KASHMIR'S 1 ACCESSION TO INDIA

ADARSH SEIN A N A N D 2

1. Historical background

(a) The origin and political situation in Jammu and Kashmir before

Indian Independence

Situated at the apex of the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent, Kashmir

is of great strategic importance owing to the fact that to its east lies

Tibet; to the north-east, Sinkiang provinces of China; to the north-

west Afghanistan and a few miles from Afghanistan lies Russian

Turkestan ; to its west lies Pakistan and to its south lies India. The

actual and potential importance invites the covetous attention of its

neighbours.

Ever since the emergence of the two independent States of India

and Pakistan in the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent on August 15, 1947,

Kashmir has figured as the most critical problem in the relations

between them. This issue of Kashmir arises out of its accession to

India. In these pages an attempt is made to study the events leading

to Kashmir's accession to India and the validity in law of that

accession.

The State of Jammu and Kashmir as it exists today was created

by the British in 1846. In order further to 'weaken the Sikhs5 3 after

their defeat at Sobraon, the British Government separated Kashmir

from the Sikh empire and 'sold' it to Raja Golab Singh, Ruler of

Jammu. By the Treaty of Amritsar 4 —notoriously referred to in

Kashmir as the Sale Deed of Kashmir—the British Government made

over to Raja Golab Singh and the heirs male of his body for ever and

in independent possession, the State of Jammu and Kashmir for a

consideration of seventy-five lakhs of British Indian Rupees.

1. The term ' K a s h m i r * as it is generally used, applies to the entire State of

Jammu and Kashmir, although in actual effect it is the name of only one part.

2. The author was a Research Student in the Faculty of Laws at the University

College, London, from where he obtained Ph.D. on his thesis " The development of

the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir " in May, 1963.

3. Hardinge to Ripon, 19 February, 1846, Ripon Papers (B.M.) Add. Mss.

40875—*' A Rajpoot State independent of the Sikhs on the right flank of our«Beas

frontier would strengthen us and weaken the Sikhs—and this I consider most

desirable ".

4. Treaty of Amritsar, March 16, 1846.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

70 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

The Dogra Rulers (i.e. Raja Golab Singh and his heirs) thus

secured not only the 'sovereignty* over the State of Jammu and

Kashmir but also its 'ownership' and so they did not hesitate to levy

very heavy taxes. Everybody and everything was taxed. " Carpenters,

boatmen, butchers, bakers, even prostitutes were taxed ". 6 At the

time of the transaction, no consideration was given to the moral effects

of the deed. An area of 84,471 square miles with a population of 2J

million was passed on to one single individual " for ever and in

independent possession". Since absolute autocracy was the principle

of political life at that time in the Indian Native States there was no

voice raised against this transaction in the State, but outside the State

there was some sympathy for the masses in Jammu and Kashmir.

"Towards the people of Gashmeer we have committed a

wanton outrage, a gross injustice, and an act of tyrannical

oppression which violates every human and honourable senti-

ment, which is opposed to the whole spirit of modern civilisation,

and is in direct opposition to every tenet of the religion we

profess ". 6

However, the rule of the Dogra rulers was " autocratic and

oppressive". 7 All high offices in the state were filled either by members

of the Ruler's own community or by men imported from the neigh-

bouring Punjab. As education spread, resentment arose against this

outside encroachment and for the first time the people of the State

united and demanded protection of their basic fundamental rights.

As a result of this demand the Maharaja gave a definition of the term

"State Subject" in 1927 and further provided that 'mulkis' (people of

the State)\vould be preferred to outsiders. This gave a new hope to

the people of the State and they began to struggle for their rights. In

1931 there was a revolt in Kashmir by Muslims, who were the

oppressed class, against communal discrimination. As a result of this

popular revolt, the Maharaja was compelled to set up an inquiry

commission under the chairmanship of Mr. (later Sir) B. J. Glancy.

The commission recommended that Muslims should be given more

representation in the services and that an Assembly should be

5. Lord Birdwood, Two Nations and Kashmir (Robert Hale, London, 1956),

p. 31.

$> Robert Thorpe, Cashmeer mis government, (Longmans Green, London, 1870),

p. 66.

7. Government of I n d i a : Kashmir^-a factual survey, p» 22.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN AN AND 71

8

established in the State . The Maharaja, on the recommendations

of the commission in 1934 established a Legislative Assembly in

Kashmir, called the 'Praja Sabha'. However the recommendation

of an elected majority in the Assembly was ignored; there was no

official majority and the legislative powers of the Assembly were very

restricted.

Previously there had been no political party in the State but in

October 1932 there was formed the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim

Conference, which for the first time met under the presidentship of

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah in Srinagar. The Conference protested

to the Maharaja against his failure to implement the recommenda-

tions of the Commission but no notice was taken of the complaint.

On January 29, 1934, Sheikh Abdullah said :

" T h e people of this country did not spill their blood for such

a mock show What hopes can the people of this country have

in this kind of representative Assembly where the dead weight of

the official and nominated majority will always be ready to crush

the popular voice " 9 .

In the same year the Conference sent another memorial to the

Maharaja demanding 'responsible government 5 but as was expected,

the Maharaja refused to consider this request either. The Muslim

Conference then called on the people to observe a 'responsible

government day1. The day was observed but very few non-Muslims

participated, so Sheikh Abdullah decided to seek non-Muslims

support. He appealed to the non-Muslims in the State to join hands

with the Muslim Conference to fight against the Government in 1937,

but unfortunately his suggestion was misrepresented as ca clever move

to deceive the minorities' 10 . However, this did not put Sheikh

Abdullah off and he kept on striving for unity among all

communities.

In 1938, Sheikh Abdullah moved a resolution in the working

committee of the Muslim Conference that the Conference should

change its name from Muslim Conference to National Conference and

that it should throw open its doors to non-Muslims. On 28th June, 1938

8. Report of the Commission appointed under the Order of His Highness the

Maharaja Bahadur, dated 12th November, 1931, to enquire into grievences and com-

plaints (unpublished).

9. All India State People's Conference: Kashmir, Bombay, 1939, p. 12.

10. Kashmir, p. 14.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

72 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

a meeting of the working committee was held to reconsider this

resolution which was passed by a majority of 17 against 3 votes. 11

Hindus and Sikhs were now able to join in the national struggle.

Realising that the people of his State were now united, the

Maharaja of Kashmir promulgated a Constitution for the State but its

most striking feature was that all powers, legislative, executive and

judicial, were inherent in His Highness 12 and the Council of

Ministers was responsible to him and not to the Praja Sabha1^.

Although the Maharaja had hoped that after the promulgation of the

Constitution the people would abandon their struggle, yet the people

of the State did nothing of the kind and continued in their struggle

for a responsible government in the State.

The " Quit India " movement, demanding the total withdrawal

of the British from the sub-continent, was started by Congress in

August 1942 in British India and found supporters in Kashmir. " I n

Kashmir the Nationalists did their best to kick up a row in support of

the Congress ", observes Bazaz u. However, the movement in India

did not have the sympathy of the All India Muslim Leauge, of which

Mr. Jinnah was the President and in Kashmir the non-nationalist

Muslims separated from the National Conference and again revived

the Muslim Conference under the Presidentship of Mr, Ghulam Abbas

with a policy similar to that of the All India Muslim Conference. An

open conflict between the National Conference and the Muslim

Conference was now inevitable. The National Conference was

fighting for responsible government in the State but the Muslim

Conference offered no co-operation.

In 1944 Mr. Jinnah, who was by then pretty certain to attain his

object of a separate State for Pakistan, visited Kashmir. He advised

the Muslims of the State to organise themselves under one banner

and on one platform 15. The Nationalists expressed themselves totally

opposed to this idea and the National Conference commanded so

11. Ibid,, p. 19. Shivpuri, S. N . : The Grim Saga, Calcutta, 1953, p. 32. Shiv-

puri's suggestion that Gulam Abbas seconded the resolution recommending the con-

version of Muslim Conference into the National Conference is not supported by any

other writer, so far as is known, and nor do the latter events lend any support to it.

12. Section 5 : Act X I V of s. 1996 (A.D. 1939).

13. Ibid, Section 7.

14. Bazaz, P. N . History of Struggle for freedom in Kashmir, Kashmir Publishing

Company, Delhi, 1954, p. 197.

15. Bazaz, P.N., op. cit, p. 212.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN ANAND 73

much respect in the State that the only public meeting which

Mr. Jinnah attended broke up amidst shouts of 'Go back Jinnah '. It is

on record that Mr. Jinnah had to be escorted to a place of safety by

the State police 16 . Mr. Jinnah was shocked and outraged at such

treatment from the predominantly Muslim population of Kashmir.

But it was obvious that, whereas in 1931 religion had played the

dominant role in arousing the passions of the Muslims of Kashmir,

by 1944 religion had been consciously divorced from politics 17. Sheikh

Abdullah, whose "whole background is one of nationalism,

secularism and left wing socialism" 18 now started the " Q u i t

Kashmir " movement in imitation of Congress's " Q u i t India " move-

ment, designed to expel the Maharaja from the State. The Muslim

Conference opposed this Movement and Gulam Abbas, the President

of the Muslim Conference described the " Quit Kashmir " movement

as a'council of despair 519 . In other words the Muslim Conference

was compelled to support the actions of the Maharaja's Government,

which it had hitherto been opposing. The Muslim Conference could

not control the tenacious resistance of the people of the State to

Mr. Jinnah's ideology and, as Brecher observes, at this stage, *' the

Muslim Conference was confronted with a profound dilemma, namely

its virulent opposition to the secularism of the National Conference,

and the realisation that its rival (Sheikh) was indispensable to its goal—

the integration of Kashmir into Pakistan " 20. Gulam Abbas appealed

to the Maharaja to release Sheikh 21 ; The Maharaja was quick to

realise the danger from the group and so the prominent Muslim

Conference leaders were also arrested 22 .

Thus, while reaction and persecution were in complete charge of

the political movement in Kashmir, the fight for independence was

in full swing in British India. On the eve of Indian Independence

two political organisations in Kashmir—the National Conference and

the Muslim Conference—were both Muslim led and largely Muslim

supported. The former claimed the support of all sections of the

people and the latter of the non-nationalist Muslims. But to achieve

anything substantial the two had to be brought together. Attempts to

16. Govt, of J a m m u and Kashmir : A conflict-between two ways of life (n.d,,

Srinagar), p. 6

17. Bazar, P.N op. cit , p . 237.

18. Lord Birdwood, "Kashmir Dilemma" in Fortnightly Review, August, 1952.

19. Times, London, 30/7/1946.

20. Brecher, Michael: The Struggle for Kashmir, p. 16.

21. Dawn, (New Delhi), 17/9/1946.

22. Civil and Military Gazette, (Lahore), 29/10/1946.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

74 KASHMIRIS ACCESSION TO INDIA

reconcile Sheikh Abdullah with Mr. Jinnah " failed because, both

men being conscious of their own position and importance, neither

could bring himself to make the first move " 23. The bad blood

between the two groups continued and later events showed that this

bad blood was largely responsible for what happened in the state

after Indian independence. Sheikh himself admitted to Mr. Joseph

Korbel in September 1948 that " t h e split in 1939 had been the

beginning of all their troubles 'V24 The significance of these events

for the purpose of this study is this: the demand of the Kashmir

people to have a responsible Government and their struggle to achieve

it are the basic causes of the constitutional changes in Kashmir since

Indian independence. Kashmir's accession to India must, it is

contended, be viewed in the general context of Kashmir's struggle for

a responsible Government, taking into account the manner in which

that struggle achieved its objective.

A British Cabinet Mission consisting of Lord Pethick-Lawrence,

Sir Stafford Cripps and Mr. A. G. Alexander, arrived in India on

March 23, 1946, in order to find a solution for the 'problem of India'.

As soon as it arrived in India, it received a telegram from Sheikh

Abdullah:

" As the Mission is at present reviewing the relationship of

the Princes with the paramount power with reference to treaty

rights, we wish to submit that for us in Kashmir re-examination

of this relationship is a vital matter because a hundred years ago

in 1846 the land and people of Kashmir were sold away by the

British for 50 lakh of British Indian Rupees. The people of

Kashmir are determined to mould their destiny and we appeal to

the Mission to recognise the justice and strength of our cause." 25

A few days later the National Conference submitted a memo-

randum to the Cabinet Mission reiterating the demand :

" Today the National demand of the people of Kashmiris

not merely the establishment of responsible Government, but the

right to absolute freedom from autocratic rule. The immensity

of the wrong done to our people by the sale deed of 1846 can only

be judged by looking into the actual living conditions of the

23. Lord Birdwood, op. cit,, p. 65

24. Joseph Korbel, Danger in Kashmir, (Princeton University Press), p. 23.

25. As quoted by Sheikh Abdullah : Address to the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent

Assembly, (November 5, 1951), p . 7.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN ANAND 75

people. It is the depth of our torment that has given strength to

our protest '\ 2 6

However, the Cabinet Mission, while admitting the claims of the

Muslim League, and Congress in British India, refused to consider the

grievances of the State's people. On 25th May, 1946, the Mission

issued a Memorandum dated May 12, 1946, regarding the State

Treaties and Paramountcy. 27 Paragraph 5 reads:

" When a new fully self-governing or independent Govern-

ment or Governments come into being in British India, His

Majesty's Government's influence with these governments will not

be such as to enable them to carry out the obligations of para-

mountcy His Majesty*s Government will cease to exercise the

powers of Paramountcy. This means that the rights of the States

which flow from their relationship to the Crown will no longer

exist and that all the rights surrendered by the States to the

Paramount power will return to the States "

This clarified the position of the State. Since the British had

dealt with the Rulers only, to the exclusion of the State's people,

therefore sovereignty would revert to them and them alone. Although

measured by the standards of western democracy it was unjust;

that was the position taken by the British Government—the pioneer of

the Western Free Democracy. The "Chamber of Princes 5 ', which

the British Government recognised, was the " Chamber of Rulers "

and not of the States' people.

His Majesty's Government made a statement on June 3, 1947, 28

and gave the plan of the transfer of power. Inter alia it provided for

the creation of two independent dominions out of the provinces com-

prising British India. The plan provided that the Muslim majority

provinces should constitute the dominion of Pakistan and the Hindu

majority provinces the dominion of India. The position of the States

was dealt with in a small paragraph :

" H i s Majesty's Government wish to make it clear that the

decisions announced above (about the partition of British India)

relate only to British India and that their policy towards Indian

States contained in the Cabinet Mission Memorandum of 12th

May, 1946 (Cmd. 6835), remains unchanged ".

26. Ibid.t p. 7.

27. Cmd. 6835.

28. Cmd. 71-36,

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

76 KASHMIRIS ACCESSION TO INDIA

This made it still clear that the communal basis of the partition

of India was not to affect the States at all, and that on the transfer of

power the States were to become independent with sovereignty vested

in the Ruler alone. The Cabinet Mission had indicated in its

Memorandum of May 12, 1946, that the States could enter into

relationship with the successor Government or Governments in

British India and Lord Mountbatten, the Governor-General of India,

addressing the Chamber of Princes on July 25, 1947, 29 told the

assembled Princes and their representatives that legally they were

independent but he advised them to accede to one or the other

Dominion before the transfer of power to ensure the continuance of

the existing relationship. He told them that they (the Rulers) were

free to accede to either Dominion and that they alone had the power

to take a decision for their States but he advised them that there were

certain "geographical compulsions " which could not be evaded. To

negotiate with the Rulers, two States Departments were established,

one for each Dominion. All except 3 Rulers acted on Lord Mount-

batten's advice and acceded to either Dominion before the date of

transfer of power. Kashmir was one of the three States which did not

accede to either Dominion, the other two being Hyderabad and

Junnagadh. In the Indian Dominion the Accession was to be made

under Section 6 of the Government of India Act, 1935, as adapted by

Section 9 of the Indian Independence Act, 1947.

A state could accede to either Dominion by executing an instru-

ment of Accession signed by the Ruler and accepted by the Governor-

General of the Dominion concerned. Legally the interest of India or

Pakistan in a particular State had no relevance; the decision whether

to accede or not and to which Dominion were not only independent of

such considerations but an exclusive right of the Ruler. 30

In Kashmir most of the leaders of the Muslim Conference and

the National Conference were in prison on 15th August, 1947, the day

of the transfer of power. But the imprisonment of their leaders did

not deter the people of the State from raising their voices and demand-

ing the establishment of responsible government. 31 Deprived of

British help, to which the Maharaja had hitherto been entitled to

29. Mouhtbatten, Lord, of Burma : Time only to look forward (Nicholas Kaye,

London), p. 52.

30. See Taraknath Das: "Status of Hyderabad during and after the British

Rule ia India " in 43 American Journal of International Law,

31. The Khidmat, (Urdu) Srinagar, 15/3/47.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN ANAND 77

u

supress internal rebellion and external aggression ", his position was

precarious. " He disliked the idea of becoming a part of India, which

was being democratised, or of Pakistan which was Muslim He

thought of independence 53 . 32 He offered to sign a standstill agreement

with both India and Pakistan with the object of continuing the exist-

ing relationship pending his final decision regarding the future of the

State. Though a standstill agreement was concluded between Kashmir

and Pakistan, for a variety of reasons no standstill agreement was

concluded between India and Kashmir. The " absence of a formal

agreement between India and the Maharaja was interpreted by the

Pakistan to mean that ultimately Kashmir would become a part of

Pakistan. 33 Lord Birdwood while dealing with this agreement has

remarked that it was just a device " which any prince could sign with

one or other of the Dominions in order to ensure that in cases where

the ruler needed more time to make up his mind, the normal services

...should continue, 31 and it would seem that Pakistan has exaggerated

the significance of the standstill agreement. But Pakistan started

putting pressure on the Maharaja to join Pakistan. Mr. Jinnah's

Private Secretary came to Srinagar and " H i s Highness was told that

he was an independent sovereign, that he alone had the power to give

accession ; that he need consult nobody, that he should not care for

the National Conference or Sheikh Abdullah that he need not

delegate any of his powers to the people of the State and that Pakistan

would not touch a hair of his head or take away an iota of his

power ", 35 if n e acceded to Pakistan. Indeed the National Conference

leaders feared that, if the state joined Pakistan, the Maharaja would

still retain his absolute power and this they resented. However, since

the Maharaja was toying with independence, he refused to take promises

literally. ".*.... that procrastinating prince hoped to triumph by

delay". 36 However events started moving faster on the Pakistan side and

on August 24,1947, Dawn, the Muslim League's official organ, wrote

"the time has come to tell the Maharaja of Kashmir that he must take

his choice and choose Pakistan. Should Kashmir fail to join Pakistan,

32. Brown, W. N. The United States and India and Pakistan, p. 162.

33. Brecher, Michael, op. cit., p. 23.

34. Birdwood, Lord, op cit., p. 45.

35. Mahajan, M. G. Accession of Kashmir to India, p. 2 (the inside story)

Mr. Mahajan was the Prime Minister of Kashmir in 1947. After that he was the

Chief Justice of the Punjab High Court and retired as the Chief Justice of India.

36. Moraes, Frank : Jawaharlal Nehru : a Biography, 1956, New York. The

Macraillan Co.* D. 385.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

78 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

i;

t h e gravest possible trouble will inevitably ensure". This threat

alarmed the Maharaja, caught on the horns of a dilemma. Pakistan

started an economic blockade against the State with a view to coerc-

ing the Maharaja to accede to Pakistan. Charges and counter-charges

were exchanged between Pakistan and Kashmir; 3 7 to substantiate or

disprove these were difficult; because of the economic blackade, there

were fresh uprisings in the State; so the Maharaja, on the advice of

his Prime Minister, released Sheikh Abdullah on September 29, 1947.

Soon after his release Sheikh Abdullah addressed a public meeting in

Srinagar. He reiterated that the main demand of the Kashmiris

was ' Freedom before accession'.33 However, he emphatically expressed

his resentment against Mr. Jinnah and said :

" How can Muslim League or Mr. Jinnah tell us that we should

accede to Pakistan ? They have always opposed us in every

struggle. Even in our present struggle (Quit Kashmir) he (Mr.

Jinnah) carried on propaganda against us and went on saying

that there was no struggle of any kind in the State. He even

termed us Goondas '\3<J

Athough this was his feeling, he told the leaders of Pakistan in the

Security Council:

"...that, whatever had been the attitude of Pakistan towards

our freedom movement in the past, it would not influence us in

our judgment. Neither the friendship of Pandit Nehru and of

Congress nor their support of our freedom movement would have

any influence upon our decision if we felt that the interests of

four million Kashmiris lay in our accession to Pakistan." 10

From a strictly legal standpoint this statement is irrelevant, for the

people had no real right to be consulted on the issue of accession.

(b) Events leading to Kashmir's accession

While all this was going on, Pakistan jumped the gun. Tribes-

men, who in language or culture had nothing in common with the

people of Kashmir, were transported across Pakistani territory to attack

the people of Kashmir and subsequently the invasion was followed

37. White Paper on Jammu andKashmir, (1948), pp. 6-14.

38. Interview with Mr. Banerji as reproduced in Banerji, J . K . : I Report on

Kashmir, (The Republic Publication, Calcutta, 1948), p. 7*

39. As quoted by Kaula and Dhar: Kashmir Speaks, New Delhi, p. 54.

40. S/P. 241 Dated 5/2/1948, p. 2.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN ANAND 79

41

up by the Pakistani Army itself. The State of Kashmir was at this

time in imminent peril and the Maharaja saw his dream of ' inde-

pendence ' collapsing like a house of cards, and as Campbell Johnson

observes, " I t is probable that nothing short of a full scale tribal inva-

sion to the gates of his capital would have induced the hesitating

Maharaja to accede at all ". 42 The tribal invasion started on 22nd

October, 1947. The State forces were not well equipped to stop the

invaders. As the position then stood, the Government of Kashmir

could ask for military help from either India or Pakistan or from any

of its other neighbours. However, to ask the military aid from

Pakistan was out of question, as the tribesmen were attacking the

State at the instance of the Pakistan Government. Margaret Bourke

White v/no has done some research on the attack records:

" Certainly these miniature ballistics establishments (the

small factories in the tribal areas) would hardly explain the

mortars, other heavy modern weapons and the two aeroplanes

with which the raiders were equipped. In Pakistan towns close to

the border arms were handed out before daylight to tribesmen

directly from the front steps of Muslim League Headquarters.

This was not quite the same as though the invaders were being

armed directly by the Government of Pakistan. Still Pakistan is

a nation with one political party—the Muslim League *\43

Therefore, the only course open to the Maharaja of Kashmir was to

ask for help from India. The Deputy Prime Minister of Kashmir

with a letter from His Highness went to the Prime Minister of India

asking for help. 14 October 24 and 25 were the most anxious days for

the State. On October 25 Mr. V. P. Menon, the Secretary of the

State Ministry of India was sent to Srinagar to " m a k e an on the spot

study' 1 by the Defence Committee. Menon stayed in Srinagar till

the morning of 26th October and then returned to Delhi to report

his impressions of the situation to the Defence Committee. He

" pointed out the supreme necessity of saving Kashmir from the

raiders" 45 and suggested sending of troops to Kashmir. The Press

Attache to Lord Mountbatten records in his diary on 28th October:

41. It has been admitted that Pakistan had given help to the tribesmen and

t ater had followed up the invasion itself. See S/955,13/9/48 and S/UOO, para 40.

42. Campbell-Johnson, Alan, op. cit, p. 240.

43. White, Margaret Bourke, Halfway to Freedom, p. 208.

44. Mahajan, M. C. op. cit, p. 14.

45. Menon, V P. The Integration of Indian States, pp. 397-99.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

80 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

" He [Mountbatten] considered that it would be the height

of folly to send troops into a neutral State where we had no right

to send them, since Pakistan could do exactly the same thing,

which would only result in a clash of armed forces and in war". 46

The only basis on which the Indian troops could go to Kashmir was

that Jammu and Kashmir State should become a part of India.

Menon had advised the Maharaja of Kashmir to leave Srinagar and

go to Jammu for the reason that ceif the Government of India decided

not to go to his rescue there was no doubt about the fate that would

befall him and his family in Srinagar 47 at the hands of the raiders,

who were in Baramula, very near Srinagar.

After the Defence Committee meeting on October 26, Menon

flew to Jammu to advice the Maharaja of the Government of India's

views, taken at the Defence Committee meeting. Had Menon not

arrived in time, the then Prime Minister of Kashmir, Mahajan

records;

" We have decided by the 25th evening to go to India if we

could get a plane, or else to Pakistan for surrender". 48

The Maharaja wanted to save the State from destruction and was

prepared to accede if necessary, as is clear from his letter to Lord

Mountbatten:

" I have accordingly decided to do so (accede to India) and

I attach the Instrument of Accession for acceptance by your

Government. The other alternative is to leave my State and my

people to free-booters. On this basis no civilised Government

can exist or be maintained. This alternative I will never allow

46. Campbell-Johnson, Alan, op. cit., pp. 244-5 ; Menon. V. P., op, cit., p. 397

records substantially the same with a difference that he does not say as to why Lord

Mountbatten did not think it proper for the Indian troops to march to Kashmir. In

fact, the statement " a s Pakistan could do just the same..." which is recorded by

Campbell-Johnson appears nowhere in Menon's book. The present writer believes

this statement to be important as otherwise there does not seem to be any justification

for the Government of India's stand that ' only if the State acceded to India could

army be sent there \ Kashmir was neutral at that time and had asked for help from

India on 'humanitarian grounds'. (Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., p. 14). It was the

fear of Lord Mountbatten that if the Indian army went to Kashmir there might

occur a war between India and Pakistan (and that he desired to avoid) which made

him demand a legal right to go to Kashmir's help.

47. Menon, V. P., op. cit., p. 398.

48. Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., p. 16.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN AN AND 81

to happen as long as I am Ruler of the State and I have life to

defend my country." 49

When Menon arrived on 26th October, an Instrument of Accession

was executed and signed by the Ruler, and Menon, accompanied by

Mahajan, left for Delhi with the Instrument of Accession and the

Maharaja's letter to Mountbatten. Mahajan, as the Prime Minister

of Kashmir, solicited army help and asked that the army be flown to

Srinagar at once. There was a long discussion at the Defence

Committee meeting regarding the acceptance of accession and it was

decided that the accession should be accepted. Lord Mountbatten,

however, insisted on coupling acceptance of accession with the will

of the people being ascertained. 50 Mahajan observes that the

Government of India was not keen about accession.51 The accession

of Kashmir to India was supported by Sheikh Mohd. Abdullah,

the leader of the All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference. 62

The reasons for Abdullah's support seem to be that he was desirous

of the State being democratised and he hoped that accession to

India would make this possible.53 Later events showed that this

was not unreal optimism, as after the accession of the State to India,

the Monarchy was abolished in Kashmir.

2. Legality of Kashmir's Accession

The Instrument of Accession, executed by Maharaja Hari Singh

and accepted by Lord Mountbatten as the Governor-General of India

was in no way different from that executed by some 500 other states.

It was unconditional, voluntary and absolute. It was not subject to

any exceptions; it bound the State of Jammu and Kashmir together

legally and constitutionally. However, after the Instrument of

Accession had been accepted by the Governor-General of India,

Lord Mountbatten wrote a semi-official letter to Maharaja of

49. White Paper on Jammu and Kashmir, p. 47.

50. Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., p. 225.

51. Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., p. 17.

52. See Mahajan, M. C, op. cit, pp. 16-17 and Menon, V. P.; op. cit., p. 400.

53. See Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., and Banerjee, J. K., op. cit, p. 9, National

Conference was the only representative party in the State actively functioning in

1947 as its only opponent—the Muslim Conference had ceased to function because

almost all its leaders were in prison. (See also Brecher, Michael, p. 108).

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

82 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

Kashmir. Among other things written in the letter it was provided

that,

" it is my Government's wish that, as soon as law and order

have been restored in Kashmir and its soil cleared of the invader,

the question of Kashmir's accession should be settled with

reference to the people." 54

This statement has figured as the most controversial feature of

Kashmir's accession to India. Critics of the accession have steadfastly

maintained that this stipulation renders the accession conditional.

The present writer is of the opinion that this statement does not and

cannot affect the legality of the accession which was sealed by India's

official acceptance. This statement is not part of the Instrument of

Accession.

" T h e Indian Independence Act did not envisage conditional

accession. It could not envisage such a situation as it would be

outside the Parliament's policy. It wanted to keep no Indian

State in a state of suspense. It conferred on the Rulers of the

Indian States absolute power in their discretion to accede to

either of the two Dominions. The Dominion's Governor-

General had the power to accept the accession or reject the offer

but he had no power to keep the question open or attach condi-

tions to it..." 55

The only documents relevant to the Accession were the Instrument of

Accession and the Indian Independence Act and, as the Constitutional

documents did not impose any conditions, there can be no question of

the accession having been conditional. " Finality which is statutory

cannot be made contingent on conditions imposed outside the powers

of the statute. Any rider which militates against the finality is

clearly 'ultra-vires' and has to be rejected". 56 But although this is

the position from the strictly legal point of view, let us consider the

effect of the 'wish* to ascertain the wishes of the people, to which

Lord Mountbatten referred. Lord Mountbatten, in expressing the

wish, was probably expressing a pious hope a declaration without

legal effect. At best it was a formal declaration of the policy of the

Government of India at that moment. But even if it was only that,

there was never any agreement between the Maharaja of Kashmir

and the Government of India regarding the ascertainment of the

wishes of the people. It was a unilateral declaration—a declaration

54. White Paper on Jammu and Kashmir, 1948, p. 47.

55. Mahajan, M. C , op. cit., pp. 19-20.

56. Ibid.,p. 21.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN ANAND 83

to which the Maharaja was never asked to agree. For any contract

to be binding, law requires ' offer ' and 'acceptance'. In this case it

would seem that Lord Mountbatten made an offer but the Maharaja

did not signify his acceptance. Lord Mountbatten's unilateral

declaration cannot be regarded as a condition attached to the

Accession; 'wish' cannot be regarded as a proposal within the meaning

of the Indian and Pakistan Contract Act.

However, Pakistan refused to recognise this accession.67 Mr. Liaquat

Ali Khan later said :

" We do not recognise this accession. The accession of

Kashmir to India is a fraud prepetrated on the people of Kashmir

by its cowardly Ruler with the aggressive help of Indian Govern-

ment". 58

The same thesis was presented by Sir Mohammed Zafarullah Khan,

Pakistan's Foreign Minister in the Security Council in 1951 and ever

since.59

It is difficult to regard this charge as anything more than abuse.

Fraud is causing a person to do something to his detriment or another's

advantage by deceit and if it be conceded that India secured an ad-

vantage by Kashmir's accession, there is no evidence of any deceit

practised by India on Kashmir. If by fraud it is meant that the

Government of India should not have accepted the Instrument of

Accession signed by the Ruler of Kashmir unless it had been endorsed

by the people, it is submitted that the Government of India had no

authority to question the right of the Maharaja to accede to the Indian

Dominion. To accede or not to accede to a particular Dominion was

the exclusive right of the Rulers. The Government of India had no

authority to ask the Maharaja to establish his right to sign the Instru-

ment of Accession. To have done so would have meant that the

Government of India was going to meddle with the internal politics

of the State. Law does not permit any such intervention in the affairs

of another State. India had no claim on Kashmir before that State

acceded to it. Pakistan has alleged that the accession of Kashmir was

procured by force. Campbell-Johnson observes, " .indeed, the

State Ministry, under Patel's direction went out of its way to take no

57. It must, however, be remarked that recognition by either Dominion was

not required for the legality of the accession. The accessidn of a State was purely a

matter between the State's Ruler and the Dominion concerned.

58. Dawn, Karachi, 5/11/1947.

59. Security Council {Vtrhatim Report) 534 ; dated 6/3/1951, pp. 6-15,

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

84 KASHMIR'S ACCESSION TO INDIA

action which could be interpreted as forcing Kashmir's hand and to

give assurances that accession to Pakistan would not be taken amiss by

India*'. 60 On his return to London Lord Mountbatten narrated :

" H a d he [Maharaja of Kashmir] acceded to Pakistan before

August 14, the future Government of India had allowed me to

give His Higness an assurance that no objection whatever would

be raised by them". 61

The Government of India would not have been in a position to raise

any objection in any case but this statement was to reassure the Ruler

that he should exercise his discretion without any fear of consequences.

When at his meeting with Lord Mountbatten on November 1,

Mr. Jinnah claimed that the accession of Kashmir to India was based

on violence, Lord Mountbatten replied "accession had indeed been

brought about by violence but the violence came from tribesmen, for

whom Pakistan, and not India was responsible". 62 Indian Law recog-

nises as voidable a contract procured by coercion but only when the

coercion was exercised by or for the party to the contract other than

the party coerced. India exercised no coercion; the tribesmen were

not acting on behalf of India and whatever their objective, it was not

to compel Kashmir to accede to India.

After Lord Mountbatten had expressed his government's 'wish',

it is argued, India might be regarded as under a moral obligation to

honour that pledge. But law does not permit any such moral

obligation to be given effect to. With the accession of the Jammu

and Kashmir State to India, jurisdiction in matters of External

Affairs, Defence and Communications was transferred to the

Government of India and the Dominion Parliament was given power

to make laws for the purposes of the three subjects only. The

Dominion Parliament, as such, had no jurisdiction in any other matter.

Sovereignty, in so far as the internal administration of the State was

concerned, remained with the Ruler by virtue of clause 8 of the

Instrument:

"Nothing in this Instrument effects the continuance of my

sovereignty in and over this State, or save as provided by or under

60. Campbell-Johnson, Alan, op. cit., p. 223.

61. Speech to the members of the East India Association, London, on June 29,

1948, reproduced in Lord Mountbatten; Time Only to Look Forward, London, 1949*

p. 269.

62. Campbell-Johnson, Alan, op*cittfpt 229.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

ADARSH SEIN AN AND 85

this Instrument, the exercise of any power, authority and right

now enjoyed by me as Ruler of this State or the validity of any

law in force in this State ",

and by virtue of Clause 7 the State did not commit itself to the

acceptance of any future constitution of India. 63 The association of

Kashmir with India was based on the Instrument of Accession and

subject to its terms and conditions, which did not give any authority

to the Government of India to hold any sort of referendum in Kashmir.

In 1950 the Constitution of India was adopted. Indian States,

other than Kashmir, executed supplementary Instruments of Acces-

sion64 and accepted the Constitution of India as the constitution for

their States and the " Instrument of Accession became a thing of the

past for those states." 65 Kashmir did not execute any supplementary

Instrument and insisted that its association should remain confined to

the terms of the Instrument of Accession, because of the peculiar posi-

tion in which the State was placed. Article 370 (Article 306-A in the

Draft Constitution) was based on the terms of the Instrument of

Accession and provided that "the power of the Parliament to make

laws for the State shall be limited to

(1) those matters in the Union List and the Concurrent List

which, in consultation with the Government of the State,

are declared by the President to correspond to matters

specified in the Instrument of Accession governing the

accession of the State to the Dominion of India as the

matters with respect to which the Dominion Legislature

may make laws for that State "

It was further provided that any exceptions and modifications in the

relationship of Kashmir with India would be made by the President

in consultation with the Government of the State.

Thus, even after India became a Republic and adopted its own

Constitution, it had no powers unilaterally to change the status of

Kashmir as Kashmir's association was still based on the Instrument of

Accession and subject to its terms and conditions.

63. It must be pointed out that the Instrument of Accession executed by the

Ruler of Kashmir was in no way different from the standard form of the Instrument

of Accession and these clauses were included in the standard form.

64. White Papers on Indian States, (1950).

65. Constituent Assembly Debates, {India), Vol. x, No, 10, p. 422.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

86 KASHMIR'S ACGESSION TO INDIA

After 1952 more parts of the Constitution of India were applied

to the State with the concurrence of the Government of that State

but even then effect would not be given to a "moral obligation" which

was not embodied in the constitutional documents. Mahajan holds,

" t h e moral grounds cannot override constitutional and statutory

provisions. Even the Directive Principles of the Indian Constitution

confer no such authority ". 66 He goes on to say, "such promises

cannot bind India They cannot deprive Rulers of their constitu-

tional powers " to accede to any Dominion they desire. Thus no

moral obligation can affect the legality of the accession. Legally no

court can take notice of a moral obligation not embodied in the Con-

stitutional documents. Moreover, the obligation is binding, if at all,

on India, but it cannot bind Kashmir. Kashmir cannot be asked to

do what the then Ruler of Kashmir never agreed to do. As such, if

there is a "moral obligation" on the Government of India to ascertain

the wishes of the people of Kashmir, it is binding on that Govern-

ment and the Indian Constitution has no provisions for such a step

in the process of amendment of a State's constitution. Although

such a rigidity in the Constitution might appear to ignore the facts of

life, that is the position.

Legally Pakistan has no locus standi in so far as the State is con-

cerned. If it claims a right over the State on the basis that the

population of the State are mostly Muslims, it is submitted that the

communal basis of partition did not effect the State ; if it claims a

right on the basis of the territory under its illegal occupation then it

is submitted that, it was the whole State of Jammu and Kashmir

which acceded to India and the fact that certain regions were made

to break away was an illegal action which cannot confer any right on

Pakistan or on anybody else for that matter. 67 The accession of the

State to India completely excluded Pakistan from the picture. Pakistan

cannot become a self-styled protector of the rights of the people of

Kashmir.

The accession of Kashmir to India, is not only legal and consti-

tutional but it is also perpetual and irrevocable. It is fully in accord

with what has happened with regard to the accession of some 500

other states. This legal aspect of the Kashmir situation, though

relevant to its solution, is often ignored.

66. Mahajan, M. C, op. cit., pp. 21-22.

67. See also Ferguson, J. P.: Kashmir—An Historical Introduction, (1961), p. 91.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Kashmir 015625Documento13 pagineKashmir 015625Mir TalibNessuna valutazione finora

- Indo-Pak RelationsDocumento65 pagineIndo-Pak RelationsRishabh Agarwal100% (2)

- Prepared By:: Toshit Chauhan Shubham Jha Deputy Moderator AdvisorDocumento25 paginePrepared By:: Toshit Chauhan Shubham Jha Deputy Moderator AdvisorAakanshi BansalNessuna valutazione finora

- A Historical and Political Perspective of Kashmir IssueDocumento14 pagineA Historical and Political Perspective of Kashmir IssueAdila Arif ChaudhryNessuna valutazione finora

- War of Independence, Which The British Call "Mutiny", Started Under The Leadership of Mughal Emperor BahadurDocumento24 pagineWar of Independence, Which The British Call "Mutiny", Started Under The Leadership of Mughal Emperor Bahadurhina.anwer2010Nessuna valutazione finora

- Struggle For Pakistan (1857-1947)Documento29 pagineStruggle For Pakistan (1857-1947)Ain rose100% (1)

- Pakistan Independence StruggleDocumento100 paginePakistan Independence StruggleMuhammad DaudNessuna valutazione finora

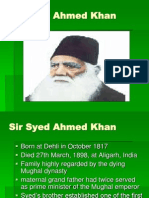

- Sir Syed Ahmed Khan Lecture 7Documento41 pagineSir Syed Ahmed Khan Lecture 7Rana MubasherNessuna valutazione finora

- Timeline History From 1857 TO 1947Documento26 pagineTimeline History From 1857 TO 1947ijaz anwarNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Policy of Pakistan (A. Sattar)Documento140 pagineForeign Policy of Pakistan (A. Sattar)Tabassum Naveed100% (2)

- Kashmir Conflict - A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir ValleyDocumento83 pagineKashmir Conflict - A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir ValleyKannan RamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lahore ResDocumento5 pagineLahore ResMoin SattiNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir IssueDocumento19 pagineKashmir IssueMahnoor HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Politics of Genocide - Punjab 1984 - 1998Documento508 paginePolitics of Genocide - Punjab 1984 - 1998navtejpvs100% (14)

- Kashmir Time LineDocumento5 pagineKashmir Time LinesaaibmirzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Solidarity Day Quiz ResourceDocumento13 pagineKashmir Solidarity Day Quiz ResourceAbdul Hadi TahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Bose Sumantra - Kashmir Roots of Conflict Chapter 1Documento17 pagineBose Sumantra - Kashmir Roots of Conflict Chapter 1Isha ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- Glancy Commission Submits ReportDocumento2 pagineGlancy Commission Submits ReportZulfqar Ahmad100% (2)

- The Emergence of PakistanDocumento11 pagineThe Emergence of PakistanHamza DarNessuna valutazione finora

- "How Carelessly Imperial Powers Vivisected Ancient CivilizationsDocumento9 pagine"How Carelessly Imperial Powers Vivisected Ancient CivilizationsSyed Ali GilaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Zubair Ayoub PST FinalDocumento15 pagineZubair Ayoub PST Finalganok balochNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Problem and SolutionssDocumento7 pagineKashmir Problem and SolutionssmubeenNessuna valutazione finora

- History Unit 2Documento14 pagineHistory Unit 2Tasaduq Ahmad 46Nessuna valutazione finora

- Political Consciousness of The Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir State 1846-1947Documento11 paginePolitical Consciousness of The Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir State 1846-1947Rajpoot KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment#03 Pak-StudiesDocumento11 pagineAssignment#03 Pak-StudiesZoya AsifNessuna valutazione finora

- MAJor Events of J&KDocumento35 pagineMAJor Events of J&KShahbaz BhatNessuna valutazione finora

- Aug or 2009Documento80 pagineAug or 2009Nayak RamalataNessuna valutazione finora

- The Tribune TT 02 July 2014 Page 9Documento1 paginaThe Tribune TT 02 July 2014 Page 9Harman SidhuNessuna valutazione finora

- Full History. Wikipedia - WPS OfficeDocumento27 pagineFull History. Wikipedia - WPS Officeifatima9852Nessuna valutazione finora

- PAK301 Short Notes by Mudasar QureshiDocumento10 paginePAK301 Short Notes by Mudasar QureshiMudassar QureshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Book 3Documento28 pagineBook 3vikashkumarchoudhary8581Nessuna valutazione finora

- Downfall of Muslim Rule: Cause and ConsequencesDocumento5 pagineDownfall of Muslim Rule: Cause and ConsequencesBilal ArbaniNessuna valutazione finora

- NC Chatterjee Commission ReportDocumento26 pagineNC Chatterjee Commission Reportsushanta_kar_orig100% (2)

- Kashmir Issue by Dr. Farooq KhanDocumento49 pagineKashmir Issue by Dr. Farooq KhanQamar ZamansNessuna valutazione finora

- Css NotesDocumento90 pagineCss NotesWaqas AmjadNessuna valutazione finora

- Allama Iqbal SermonDocumento5 pagineAllama Iqbal SermonUsman ShamsNessuna valutazione finora

- From Jinnah To Zia Long - 16 - To - 112 PDFDocumento26 pagineFrom Jinnah To Zia Long - 16 - To - 112 PDFabuzar4291Nessuna valutazione finora

- History Test Explanations EMDocumento26 pagineHistory Test Explanations EMmvnreddy.111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Definitions of EducationDocumento26 pagineDefinitions of EducationUshna KhalidNessuna valutazione finora

- KashmirDocumento10 pagineKashmirChirag SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Political Events From 1940 To 1947Documento3 paginePolitical Events From 1940 To 1947MAWiskiller50% (4)

- Kashmir Conflict:: A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir Valley & Proposed Future SolutionsDocumento83 pagineKashmir Conflict:: A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir Valley & Proposed Future SolutionsRavi RavalNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucknow PactDocumento38 pagineLucknow PactAamir MehmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- 'Final Paper (Pakistan Studies)Documento7 pagine'Final Paper (Pakistan Studies)Abdul BasitNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedom StruggleDocumento35 pagineFreedom StruggleSwiss KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucknaw Pact 1916Documento5 pagineLucknaw Pact 1916Mustakin KutubNessuna valutazione finora

- Lahore Resolution Pakistan Studies (2059)Documento6 pagineLahore Resolution Pakistan Studies (2059)emaz kareem StudentNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir and IndiaDocumento22 pagineKashmir and IndiaHamza QureshiNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Pakistan and Freedom StrugglesDocumento55 pagineHistory of Pakistan and Freedom StrugglesFabihaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Chapter 2Documento5 pagineSummary of Chapter 2Ushna KhalidNessuna valutazione finora

- Pakistan Studies: Chapter 1: Ideology of PakistanDocumento20 paginePakistan Studies: Chapter 1: Ideology of PakistanShoaib ShahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Odyssey of Freedom by Farooq RehmaniDocumento36 pagineKashmir Odyssey of Freedom by Farooq RehmaniTaseen FarooqNessuna valutazione finora

- Lahore Resolution AssignmentDocumento3 pagineLahore Resolution AssignmentMark Manson100% (2)

- Elections (1937) and Congress Ministries (1937-39)Documento10 pagineElections (1937) and Congress Ministries (1937-39)Abdul RafayNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Kashmir IssueDocumento8 pagineResearch Paper Kashmir Issueihxeybaod100% (1)

- Hridoy Hossen 3Documento17 pagineHridoy Hossen 3Re DuNessuna valutazione finora

- Khaksar Tragedy (1940) : OrganizationDocumento4 pagineKhaksar Tragedy (1940) : OrganizationNoshki NewNessuna valutazione finora

- A People's Constitution: The Everyday Life of Law in the Indian RepublicDa EverandA People's Constitution: The Everyday Life of Law in the Indian RepublicValutazione: 2.5 su 5 stelle2.5/5 (2)

- KashmirDocumento58 pagineKashmirMahamnoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Oct 07 Kashmir PDFDocumento44 pagineOct 07 Kashmir PDFAhber ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Forum Gazette Vol. 1 No. 8 September 16-30, 1986Documento16 pagineThe Forum Gazette Vol. 1 No. 8 September 16-30, 1986thesikhforumNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Studies Mcqs Comp - IFZA MUGHALDocumento16 pagineKashmir Studies Mcqs Comp - IFZA MUGHALAmirNessuna valutazione finora

- 1996 Kashmir, 1947 - Rival Versions of History by Jha SDocumento163 pagine1996 Kashmir, 1947 - Rival Versions of History by Jha Sayush100% (1)

- Azad Jammu & Kashmir Public Service Commission (Aj&K PSC) Kashmir Studies & English PortionDocumento55 pagineAzad Jammu & Kashmir Public Service Commission (Aj&K PSC) Kashmir Studies & English PortionHabib MughalNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Age: Budget Session Begins With President'S Maiden AddressDocumento8 pagineStudent Age: Budget Session Begins With President'S Maiden AddressthestudentageNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Era of BlunderDocumento72 pagineKashmir Era of BlunderimadNessuna valutazione finora

- Dasgupta - Jammu & KashmirDocumento22 pagineDasgupta - Jammu & Kashmirapi-3720996100% (1)

- Class 12 Regional AspirationDocumento31 pagineClass 12 Regional AspirationPrince KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Do Kashmiris Need Self-Determination?: UncategorizedDocumento16 pagineWhy Do Kashmiris Need Self-Determination?: UncategorizedFarooq SiddiqiNessuna valutazione finora

- Party Systems in India: Patterns, Trends and Reforms Mahendra Prasad Singh Krishna MurariDocumento48 pagineParty Systems in India: Patterns, Trends and Reforms Mahendra Prasad Singh Krishna MurariVanshika SalujaNessuna valutazione finora

- His Highness Maharaja Hari SinghDocumento30 pagineHis Highness Maharaja Hari SinghSyed Ashique Hussain Hamdani100% (1)

- Jammu and Kashmir - WikipediaDocumento176 pagineJammu and Kashmir - Wikipediachaitanya200039Nessuna valutazione finora

- Regional Aspirations (CH-8) Notes in English Class 12 Political Science Book 2 Chapter 8 in English - Criss Cross ClassesDocumento1 paginaRegional Aspirations (CH-8) Notes in English Class 12 Political Science Book 2 Chapter 8 in English - Criss Cross Classesgurkamal SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- 31 Aug The Statesman PDFDocumento12 pagine31 Aug The Statesman PDFSumair Khan MasoodNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 Feb Daily ExcelsiorDocumento14 pagine15 Feb Daily ExcelsiorurhanNessuna valutazione finora

- SIMI Fictions TehelkaDocumento68 pagineSIMI Fictions TehelkaMuhammedAfzalPNessuna valutazione finora

- November 02 2013 PDFDocumento8 pagineNovember 02 2013 PDFthestudentageNessuna valutazione finora

- Publisher's Note: Nishan, Do Vidhan, Do Pradhan" Detailing The History ofDocumento14 paginePublisher's Note: Nishan, Do Vidhan, Do Pradhan" Detailing The History ofRajesh TiwariNessuna valutazione finora

- 23Dec-Hidustan Times DLDocumento24 pagine23Dec-Hidustan Times DLBhakti and YogaNessuna valutazione finora

- Icici Ie Delhi 24 12 2020 PDFDocumento21 pagineIcici Ie Delhi 24 12 2020 PDFRaushan Kumar 43Nessuna valutazione finora

- Book2 TimelineDocumento30 pagineBook2 TimelineSaahi NandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Party System in Jammu and KashmirDocumento3 pagineParty System in Jammu and KashmirNajeeb HajiNessuna valutazione finora

- Epilogue Magazine, August 2010Documento60 pagineEpilogue Magazine, August 2010Epilogue MagazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Epaper DelhiEnglish Edition 20-06-2018Documento16 pagineEpaper DelhiEnglish Edition 20-06-2018Vijay AryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Reform Measures in Kashmir During Dogra RuleDocumento18 pagineLand Reform Measures in Kashmir During Dogra RuleEesha Sen ChoudhuryNessuna valutazione finora

- Wajahat Habibullah Kashmir The TragedyDocumento13 pagineWajahat Habibullah Kashmir The Tragedysunaina sabatNessuna valutazione finora

- National Conference and Rise of Political Awakening in KashmirDocumento12 pagineNational Conference and Rise of Political Awakening in KashmirDr Showkat Ahmad DarNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Kashmir: Kashmir: A Historical BackgroundDocumento19 pagineHistory of Kashmir: Kashmir: A Historical BackgroundWani ZahoorNessuna valutazione finora