Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Danse Macabre in London

Caricato da

Ambar CruzCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Danse Macabre in London

Caricato da

Ambar CruzCopyright:

Formati disponibili

a

The Dance of Death in London:

John Carpenter, John Lydgate, and

the Daunce of Poulys

Amy Appleford

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

How does a city, the “unintentional and unexpected result” of a “coevo-

lutionary interaction of nature and culture,” represent itself to itself? The

question lies latent in the study of any “socio-spatial construct” that is a

city. For it is a general feature of the “urban fact” that its singular identity

as a political, geographical, and cultural entity faces an irreducible tension

with the diversities that shape it. This tension is evident whether consider-

ing diversities of topography (districts, parishes, squares, roads, hills, riv-

ers), jurisdiction (civic, religious, royal), or of a city’s multiply classified and

stratified human inhabitants.1 As John Fitzherbert’s 1523 Boke of Surueyeng

and Improumetes notes, anyone who would attempt to map even the mate-

rial features that make up a city like London cannot responsibly observe it

from the high ground surrounding it. Rather, the ethical and conscientious

surveyor must seek out a multiplicity of perspectives, many of them within

the city, and must be willing even to enter its buildings:

The surueyour may nat stande at Hygate/ nor at Shootershyll/

nor yet at the Blackheth nor such other places/ and ouer loke the

cytie on euery syde. For and he do/ he shall nat se the goodly

stretes/ the fayre buyldinges/ nor the great substaunce of richesse

conteyned in them/ for than he maye be called a disceyuer & nat

a surueyer.

To “see” the city in a socially useful manner (not as a “disceyuer”), the sur-

veyor must take into account its complex artifactual nature: the aesthetic

properties (“fayre buyldinges”), rational design (“goodly stretes”), and eco-

nomic activity (“substaunce of richesse”) that constitute it as a surveyable

entity. This despite the fact that these features cannot by definition all be

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 38:2, Spring 2008

DOI 10.1215/10829636-2007-027 © 2008 by Duke University Press

seen at once, since the density characteristic of any environment worth sur-

veying requires that they stand in one another’s way.2

As with a city’s natural and human topography, so with its culture.

Modern literary scholarship on late medieval London has recently focused

a good deal of attention on the conceptual difficulties involved, both for

medieval poets and for scholarship itself, in representing something as inher-

ently resistant to representation as the city. Following David Wallace’s influ-

ential description of the metropolis as a notable absence in Chaucer’s poetry

and, more generally, as “difficult to imagine,” Ardis Butterfield has empha-

sized the city’s “opacity” for Chaucer, discerning the presence of a “gap in

the language of the city” in his writing that has the status of an “aporia.”3

Calling for an end to the “critical game of hunt-the-London,” Ruth Evans,

too, allows London only a “powerful virtual presence” in the poet’s work.4

In partial reaction to this dematerialized but implicitly unitary account of

medieval England’s largest city, others characterize the London manifested

in medieval literary texts in the language not of absence but of excessive and

multiple presence, as a community in pieces: as a diverse entity defined by

“blurred boundaries” and full of the “clash of mercantile and military inter-

ests”; as a “resistant and fragmented locality” characterized by conflict; and

as a culture and polity unable “to speak with a single voice.”5

I suggest in this article that producers of cultural images in fifteenth-

century London also found their heterogeneous and maddeningly change-

able environment difficult to represent — despite the fact that for them, as

for Fitzherbert, there was often no choice but to do so, since at all levels

representation of the city could be a powerful and necessary tool of interven-

tion in its affairs. In particular, I demonstrate how one member of the city’s

governing body, John Carpenter, situates and deploys a specific image of

death, the Daunce of Poulys, a series of panel paintings, to create an appro-

priate, though refracted, image of the London polity. Death is a subject

equally resistant to representation as the city. As Augustine famously notes,

death lies just beyond the reflexes of language; the moment of death is inef-

fable, located as it is in the negative space between “before death,” when

the dying person “cannot be said to be in death,” and after death, when

“death is [already] past.”6 But death as a phenomenon is horribly concrete;

death as a real-world transformation of a living being into insentient mate-

riality presents an unthinkable and excessive physical factualness. Because

death is both abstract and concrete at the same time, it has to be represented

obliquely, by associated signs, by images not strictly belonging to it. As Ken-

neth Burke points out in The Rhetoric of Religion, in this way, “talk” of death

286 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

can always lend itself to indirect or refracted discussions of other topics, such

as sex, political rebellion, or oppression, or apophatic subjects, such as God

or the transcendent.7

In the case of the Daunce of Poulys, death is used to create a con-

ceptually sophisticated image of the city of London, in order to counter a

particular, local problematic of franchise. Socially and politically useful but

not straightforwardly didactic, this long-destroyed, but still well-known

London wall monument — the result of a collaboration between a poet

and a bureaucrat — is a striking example of the construction of an image of

England’s capital city as a diverse yet coherent association of people other-

wise fragmented along numerous internal divides.

The Dance of Death

The Daunce of Poulys was commissioned, probably about 1430, by John

Carpenter, the common clerk of London, and painted on panels hung on

the inside walls of the cloister enclosing the cemetery known as the Pardon

Churchyard, on the northwest side of St. Paul’s Cathedral (see fig. 1). Both

the cloister and the motif of the Dance of Death itself were recent creations.

The cloister, built by order of the dean of the cathedral, Thomas More, may

have been finished as late as 1421.8 The earliest known Dance of Death was

painted in the cemetary of the Church of the Holy Innocents in Paris in

1424 – 25 on its southern wall, along the ten arcades of the Charnier des

Lingères. The verses accompanying the images in the Daunce of Poulys were

derived from John Lydgate’s “pleyne translacioun / In Inglisshe tunge” of

the text of the Holy Innocents mural, probably made in 1426, during the

English occupation of Paris when the poet was in the city. Certain “French

clerks,” as he claims in the prologue to his poem, encouraged him to bring

the new ars moriendi home to England.9

Neither the Holy Innocents’ nor the St. Paul’s images survive: the

Daunce of Poulys, “artificially and richly painted,” in Stow’s words, was

destroyed in April 1549, by order of Protector Somerset; and the south char-

nel of Holy Innocents was demolished during road works in 1669.10 Guyot

Marchant’s woodcuts in the 1485 edition of the Danse Macabré are tradition-

ally considered to be closely modeled on the painting at Paris, but this is con-

jecture; changes have been made in these images to the costume (updated

from garb of the 1420s to that of the 1480s), and some of the figures do not

appear to match their descriptions in the poem.11 Moreover, in the absence

of any visual evidence — except an amateur reconstruction of a small, badly

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 287

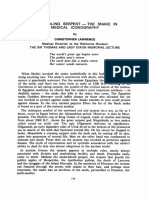

Figure 1.

Map of Old St. Paul’s by Tracy (New Haven, Conn.: Yale

Wellman in St. Paul’s: The University Press, 2004), 42. Used

Cathedral Church of London, by permission of Yale University

604 – 2004, ed. Derek Keene, Press.

Arthur Burns, and Andrew Saint

damaged, and now covered over late-fifteenth-century imitation of the

Daunce of Poulys from the Guild Chapel at Stratford-on-Avon — it is not

clear how far, if at all, the English images were modeled on their Parisian

prototypes, not least because Lydgate’s poem makes numerous changes to

the cast of characters featured in the French, especially in his introduction of

several female characters. Nor is it clear, similarly, how the several surviving

Dances of Death from Brittany, Lübeck, Inkoo, and elsewhere, and even the

surviving fragments from England and Scotland — resonant though these

examples may be — are relevant to the present study.12

From reading Lydgate’s poem in the B version, likely revised (as

we shall see) specifically for the Paul’s churchyard project, we can imagine

a dance in which partners join hands and form a processional line or circle,

ranged round the sides of the Pardon Churchyard, with eight or nine pairs

of images to a side. Each of the poem’s formally independent pairs of stanzas

consists of Death’s address to a particular estate, describing the end that now

suddenly awaits it, and that estate’s resigned reply. The estates are organized

288 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

in a rough hierarchy, with ecclesiastics and laypeople in equally rough alter-

nation: Pope, Emperor, Cardinal, Empress, Patriarch, King, and on down

to characters of middle rank, Mayor, Carthusian, Gentlewoman, Astrono-

mer, Merchant, Canon, and on again to characters of humble rank, Artisan,

Labourer, Child, and finally Hermit.

Although the Dance of Death has often been taken as emblematic

of late medieval Christian religiosity, Lydgate’s poem has not until recently

been closely or creatively studied. Even now when the Dance of Death topos

is mentioned by scholars, it is usually presented either as a manifestation of

the putatively death-oriented spirit of the age, or utopically, as an expression

of the apocalyptic conception of death as the leveler of social distinction. Paul

Binski, for example, presents an elegant reading of the figure of Death in the

Dance as a democratic force that extinguishes class distinctions and ushers in

an egalitarian next world. With their “fotyng so savage,” the dancing corpses

are anarchic figures of alterity, destroying the hierarchic arrangement of the

social world — “The living step cautiously, the dead with uncannily enthu-

siastic high kicks: the dead by virtue of their movement are another order,

another class.”13 However, in his ground-breaking book on fifteenth- and

sixteenth-century literary culture, Reform and Cultural Revolution, James

Simpson offers for the first time a reading of the sociopolitical resonances

of Lydgate’s poem, presenting it as a literary artifact that, in its “highly seg-

mented” form presents a “shorthand image” of a society structured as “a com-

plex set of self-enclosed and overlapping jurisdictions.”14 Each figure invited to

dance articulates his or her own source of temporal power before succumbing

to the absolute authority of Death: the Bailiff, for example, is called to come

to “a newe assisse / Extorcions and wronges to redresse” (Ellesmere, 267– 68).

In this argument, Lydgate’s poem, alongside its universal message of the truth

of human powerlessness in the face of death, presents English culture as a

finely articulated complex, with each regime — legal, mercantile, monarchic,

religious — constituting its own semiautonomous administrative realm.

Simpson’s reading of the Daunce of Poulys shows how the poem

offers a mimetic representation of the shape of fifteenth-century culture in

its complexity and the vivid integrity of its parts. This reading of the poem

is fundamental to the overall argument of his book, as the society the poem

describes and its disjunctive aesthetic throws into stark relief what Simpson

describes as the unified, authoritarian power and poetic structures of the

Tudor regime. Yet, perhaps in part because it turns the poem’s face, as it

were, toward the next century — and because in doing so it takes the image

produced by late medieval cultural makers as an ideologically disinterested

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 289

image of the whole of English culture — the reading also leaves a good deal

more to be said. In its focus on Lydgate’s poem in terms of its morphol-

ogy, it particularly neglects the wall painting’s function in its original civic

and urban milieu, failing to register the oddness of the fact that the Dance

makes what appears to be only its second appearance in Europe as a civic

monument commissioned by a secular bureaucrat.

Why did the Dance of Death motif appear in that time on that par-

ticular set of walls in the center of London? Why and how could a London

civil servant have a procession of corpses displayed on the side of the city’s

cathedral? The French poem is associated with — though probably not writ-

ten by — the prolific religious educator Jean Gerson, whose vernacular writ-

ings for the laity gave a central place to death and learning to die. The Paris

mural itself was an ecclesiastic production, and its location on the inside of

the south charnel wall — facing the “commerce and disorderly behavior” that

occurred in the cemetery’s open center — was a smart bit of pastoral place-

ment.15 By contrast, the St. Paul’s painted panels were the production of a lay-

person — a member of the civic secretariat — and a poet-monk who, writing

under the patronage of a series of secular figures, whether royal, aristocratic,

or mercantile, specialized in the blending of the religious and the civic; while

their chosen location was, by comparison with the Holy Innocents, strik-

ingly secluded, as a result of the churchyard’s enclosure by Dean More. Also,

apparently, deliberately secluded, for around the time he apparently arranged

for the Dance of Death to be painted, Carpenter was granted licence to estab-

lish a chaplain in a chapel of the Virgin Mary situated in the charnel house in

the northeast corner of St Paul’s churchyard.16 This charnel, containing cen-

turies of remains of London citizens and the tombs of three mayors, faced St

Paul’s cross, a gathering place for preachers, book sellers, hawkers, buyers, and

city folk, and the historic location of the folkmoot (outlawed in the 1320s), a

locale of great significance in the city’s memory. As a religious site memorial-

izing the dead in full view of the secular bustle of the churchyard, the charnel

would have offered a natural location for the Dance of Death panels, where

they could be seen by the largest number of people in a setting similar to the

Holy Innocents. But instead, Carpenter arranged to have the Dance painted

for the newly enclosed Pardon Churchyard, away from the yard and the gen-

eral populace, a decision sufficiently particular as to ask for a closer look at the

Daunce of Poulys and what it means.

This revisiting of the Daunce of Poulys approaches the poem not

simply as a representation of the multiple authority structures of fifteenth-

century London but as a specifically civic monument that was above all

290 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

intended as an intervention in those authority structures — as part of a long

struggle on the part of the city’s governors for cultural dominance over other

London jurisdictions. The analysis begins by taking a closer look at the com-

missioner of the Daunce of Poulys, John Carpenter, and his role in London’s

civic culture. It then turns to the poem itself, in the careful adaptation of

Lydgate’s original translation that was probably undertaken for its chosen

location in the Pardon Churchyard, the B version of the poem. Finally, I

will consider how exactly the poem promotes the interests of civic London:

as a spatial practice on the wall of the cathedral; and as an aesthetic image of

political community that emphasizes diversity and temporality, an imagina-

tion much more relevant to the city’s political structure than the common

metaphorization of the social body as an incorporated, organic whole.

John Carpenter

John Carpenter became common clerk or “secretarius” of the city of London

in 1417, succeeding John Merchaunt, for whom he had served as a clerk while

still working as a lawyer in the city courts. He held the post until 1438, after

which he continued to be consulted on questions of city custom; in 1440 he

was awarded twenty marks for these services. Carpenter also represented the

city in Parliament in 1437 and 1439 and, from his numerous appearances

in the city court records, seems to have been a popular choice for feoffee

or trustee, executor, and mediator in legal disputes. He was involved in the

bequests of several wealthy Londoners and was a powerful promoter of the

interests of the city’s elite, living and dead, as he was of the city’s interests in

general against those of competing authorities, especially the institutional

church. He intervened several times, for example, to challenge ecclesiastical

laws of sanctuary, on the grounds that the practice of sheltering criminals in

churches was disruptive to civic order. In 1431, he won from Parliament the

power to distrain lands left by Sir John Pulteney, former mayor of London,

from the master and priests of Corpus Christi College, for failing to honor

their commitment to pay four marks a year for relief of the prisoners of

Newgate. Carpenter’s most notable activities in this vein, however, were as

an unusually interventionist chief executor of the will of Richard Whitting-

ton — wealthy merchant, thrice mayor of London, and important creditor

to the Crown — in which role he seems to have conceived and overseen the

creation of three important charitable foundations paid for from the Whit-

tington estate: the College for Priests at St. Michael Paternoster, the Whit-

tington almshouse, and a library at the Guildhall. The first foundation is a

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 291

notable example of a civic involvement in the provision of priests for Lon-

don’s many parish churches, while the second and third were highly unusual

in that they had lay rather than ecclesiastic overseers.17

Carpenter’s work for and with the Whittington estate — particu-

larly in the creation of the Guildhall library as an intellectual resource for

London’s lower clerisy and members of the guilds18 — brings together several

concerns that recur throughout his career and characterize his commission-

ing of the Daunce of Poulys in particular: his desire to expand the reach of

civic power in both temporal and spiritual terms; his at once pietistic and

bureaucratic use of texts and belief in the power of lay education as an instru-

ment of that expansion; and his careful, often individual, deployment of the

symbols, monuments, and legal instruments surrounding death for the same

purpose. Similar concerns are evident in his own will, proved in 1442, which

not only places his estate firmly in lay and civic hands but also seeks to limit

the oversight of his bequests by an ecclesiastical officer. After his many spe-

cific bequests (including one to his friend and executor, Reginald Pecock,

then master of the third of Whittington’s foundations, the College of Priests),

Carpenter left the residue of his estate to be disposed of “in works of piety

and mercy” with the condition that they not make “any inventory of such my

goods and chattels to any ordinary,” even leaving the “ordinary” — bishop of

London, Robert Gilbert — the sizable amount of “twenty shillings sterling” if

the clause were honored.19 Included in these uninventoried assets were most

of Carpenter’s large collection of French, Middle English, and Latin books

of theology and religion, a private collection Caroline Barron characterizes

as “one of the most extensive . . . to be found in fifteenth-century London,”

which Carpenter left to the Guildhall library.20

As Wendy Scase has shown, Carpenter had several connections with

the devout London lay community behind the John Colop common-profit

book scheme;21 his evident view that it was in the interests of the city to

promote widespread access to the “common profit” and power of the writ-

ten word is clearly linked not only to his status as a devout and politically

powerful layman but to the specific nature of his profession. As common

clerk, his primary domain was the documentary culture that defined the

enfranchisement of the city: the proclamations he signed in the name of the

mayor, aldermen, and commonalty; the court records he was entirely respon-

sible for maintaining; the financial records of the city he alone could access.

It is in this context that we should also view the project for which he is best

known, and which again brings together the themes of civic jurisdiction, the

written word, and death: the massive Liber Albus from around 1421, written

292 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

early in his career as common clerk, perhaps in emulation of a comparable

work, the Liber Horn, written by his most ambitious predecessor, the early-

fourteenth-century chamberlain of the city, Andrew Horn.22 The Liber Albus

is an exhaustive attempt to organize all the archival material surviving since

the founding of London; to set down the customs of the city, as they pertain

to the distribution and passing on of power in the city’s government; and to

detail the history and duties of the elected governors and officials that make

up the civic hierarchy: all, as Carpenter’s introduction states, in order to cir-

cumvent, so far as possible, the unexpected and irresistible power of death.

Because “the fallibility of human memory and the shortness of life do not

allow us to gain an accurate knowledge of everything that deserves remem-

brance,” unless knowledge is recorded in highly codified form, and because

death often comes suddenly to the “aged, most experienced, and most discreet

rulers of the royal City of London,” causing disruption to their successors, it is

crucial to have in writing how the power structure reproduces itself.23

Carpenter’s bureaucratic adaptation of the literary language of

eternalization here has been variously understood. Ethan Knapp suggests a

parallel between Carpenter’s concern with the stability of the written word

and that of the chancery clerk Thomas Hoccleve, for whom, Knapp argues,

poetry is a stabilizing force in an otherwise precarious career of dependence

on the turbulent power dynamics of the court. Sheila Lindenbaum, on

the other hand, argues that Carpenter’s organization of the customs, legal

records, and ordinances of disparate parts of the city government into one,

massive, cross-referenced volume works to reinforce the London oligarchy’s

self-representation as a “single authoritative entity.”24 But these readings can

usefully be nuanced in two ways.

First, unlike clerks of the Privy Seal such as Hoccleve, Carpenter’s

situation as common clerk of London was far from precarious. Where top

officials in the city’s government (mayors and sheriffs) were elected annually

and the senior civic bureaucrat, the recorder, took the job as a stepping stone

to royal appointment, the position of the common clerk was a full-time,

fully professional position; often held for decades at a time, it bestowed con-

siderable authority even on much less activist figures than Carpenter, who

was uniquely positioned as Whittington’s executor to engineer the rebuild-

ing and reorganization of significant areas of public space. Far from being

in Hoccleve’s poignant relation to the literary language of eternalization,

Carpenter must have seen his documentary project more as an extension of

his own role and its necessarily almost absolute job security.

Second, the Liber Albus does clearly attempt to promote and pro-

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 293

tect the power of the civic government, not only against death but against

more worldly threats to its sovereignty, especially the competing claims of

the church and the Crown. Yet far from serving as an arm of the London oli-

garchy in any straightforward way, the introduction to the Liber Albus sug-

gests Carpenter’s intention to replace the minds and memories of members

of the city’s elite with the beautifully cross-referenced written technology of

his compilation. In the Liber Albus, power is depersonalized, abstracted, and

inheres primarily in texts, allowing governance of the city to pass smoothly

from one generation of expendable governors to another, thanks to how the

forms of authority are made perpetual in its pages. This abstraction and

expendability ultimately extends to Carpenter himself as common clerk; but

it also makes Carpenter the “secretary,” not of Richard Whittington, Robert

Chichele, or any particular city ruler who happens to be the year’s mayor but

to the corporation of London itself.

Carpenter was expert at manipulating various registers of documen-

tary culture in his position as common clerk. In his collaborations with John

Lydgate, he extended his reach into the domain of vernacular poetics and,

through it, reached a wider civic audience.25 Besides working together on

the Daunce of Poulys, Carpenter and Lydgate collaborated on an account of

Henry VI’s entry into London in February 1432, Lydgate’s poem on the topic

being based on a long Latin letter by Carpenter which describes a program

of seven pageants that the two writers may have devised together. As several

critics have recently noted, by contrast with the city’s earlier royal entry pag-

eant for Henry V in 1415, where the king was identified with powerful Old

Testament figures like King David, this entry is as much a celebration of the

London civic oligarchy — especially the mayor and aldermen, clothed, we are

told, in dashing red and scarlet and “estately horsed” — as it is a celebration of

the ten-year-old king. Within their posture of deference, the pageants work

to instill in Henry VI an attitude of gratitude and humility in relation to the

city.26 In Lydgate’s version of the event, the mayor, aldermen, and other wor-

thy citizens of London lead the king in procession through the streets of the

city, stopping at seven fixed stations. At each tableau, the king is offered the

“gifts” the city feels he needs to be a successful sovereign: “sciens,” “kunnyng,”

“strenth,” “ffeyrenesse,” gifts the city already enjoys (524 – 30). In the envoy,

the poem is presented to the “noble Meir” and, in the poem proper, London

is told it should “thanke God off alle thyng, / Which hast this day resseyved

so thy Kyng, / With many a signe and many an obseruaunce / To encrese

thy name by newe remembraunce” (513 –16) — not, noticeably, to increase

the name of the king. Here, the necessity of staging an entry for the king is

294 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

made an opportunity to celebrate London’s identity as “Newe Troy” (512).

In the Daunce of Poulys, the city, through its secretary, Carpenter, and its

poet, Lydgate, similarly manipulates a traditional discourse — in this case

the topos of memento mori — to insist on its autonomy from, and ability

to hold its own against, alternate and competing sources of sociopolitical

authority, namely, the church and the Crown.27

The Daunce of Poulys

Lydgate’s poem on the Dance of Death survives in two main versions, which

have been rather awkwardly edited in a parallel-text format that makes it

difficult to reconstruct the substantially reordered and rewritten B version.

But, despite this technical difficulty, it is important to distinguish one ver-

sion from the other, since the two appear to serve different agendas. The A

version, probably the immediate product of Lydgate’s 1426 visit to the Holy

Innocents, is a fairly close translation of the French poem, although it adds

six figures, four of them women, to the Danse Macabré’s exclusively male cast

of characters: an Empress, a Lady of Great Estate, an Abbess, an Amorous

Woman, a Juror, and a particular Tregetour or magician named Jon Rikelle.

This last figure in particular suggests the A version was composed for a spe-

cific, likely courtly, context. The B version, which I take to be Lydgate’s

revision for the Daunce of Poulys project (not least because it bears the title

Daunce of Poulys in two manuscripts), reorders the A version in a number

of places and omits several characters from this version while adding eight

new ones, seemingly with a powerful London civic audience in mind. The

number of courtly figures is reduced from twelve in the A version to eight

in the B, which compresses the Squire and Knight into one figure and omits

the Lady of Great Estate, the Lover, and the Tregetour. The B version also

reworks several figures, both secular and ecclesiastic, that belong specifically

to an urban community, rendering the estate designations more precise. The

character of the Canon doubles to become the Canon Regular and Dean or

Secular Canon (the latter perhaps as a nod to Dean More who built the Par-

don cloister or to his successor, Reginald Kentwood, who allowed the Daunce

to be installed), and these figures are joined by a nun or semi-religious, the

Woman Sworn Chaste; the Man of Law turns into the Sergeant of Law and

is joined by the Doctor of Canon or Civil Law.28 The Merchant is joined by

his competing craft category of Artificer or artisan, and the category of civic

government (absent in the French and the A version) is represented by the

figure of Mayor and a city servant, the Famulus (see table 1).29

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 295

Table 1.

Comparison of characters from The Danse Macabré and the A and B Versions of Lyd-

gate’s Daunce of Poulys.

French Version (Additional) Lydgate A (Ellesmere MS) Lydgate B (Lansdowne MS)

Pope Pope Pope

Emperor Emperor Emperor

Cardinal Cardinal Cardinal

— Empress (in most A MSS) Empress

King King Patriarch

Patriarch Patriarch King

Constable Constable —

Archbishop Archbishop Archbishop

Knight Baron or Knight1 Prince (compare Constable)

— Lady of Great Estate —

Bishop Bishop Bishop

Squire Squire2 Earl or Baron1

Abbot Abbot Abbot/Prior

— Abbess Abbess

Bailiff Bailiff —

Master Astronomer3 Justice

Burgess Burgess —

Canon Canon4 Doctor of Canon/Civil Law

Merchant Merchant5 Knight or Squire2

Carthusian Carthusian6 Mayor

Sargeant Sargeant7 Canon Regular

Monk Monk —

Usurer Usurer —

Poorman Poorman —

Doctor Doctor8 Dean or Canon4

Lovers Lover —

—- Gentlewoman Amorous9 Woman Sworn Chaste

Lawyer Man of Law10 Carthusian6

— Juror 11 Sargeant7

Minstrel Minstrel12 Gentlewoman9

— Tregetour —

Priest Priest —

Labourer Labourer13 Astronomer3

Friar Friar Friar

Child Child14 Sergeant in Law10

Clerk Clerk —

Hermit Hermit15 Juror11

296 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

Table 1. (continued)

French Version (Additional) Lydgate A (Ellesmere MS) Lydgate B (Lansdowne MS)

Minstrel12

Officer or Famulus

Doctor8

Merchant5

Artificer

Labourer13

Child14

Hermit15

Note: Characters are listed in order of appearance, and names are normalized and anglicized. Char-

acters new to Lydgate’s A version that also appear in the B version are indicated by italics; characters

new to the B version only are indicated by boldface. Superscript numbers next to Lydgate’s characters

show their relative order of appearance in the two versions.

The finer articulation of the society portrayed by the B version

underlines the poem’s focus on social anatomization, its preoccupation with

temporal authority, and its organization of characters in relation to the world

of labor, all aspects Jill Mann isolates as characteristic of estates literature

such as the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales.30 Some of the char-

acters of the Daunce are satirical stereotypes, favorites of the estates mode,

such as the Abbess, (“With your mantyl furryed large & wide / Your veile

your wympil your ring of gret richesse” [194 – 95]), whose sensuality and fine

clothes have precedents in the descriptions of worldly nuns, as in the satirical

sermon collection Sermones nulli parcentes.31 The response to Death of the

Knight or Squire, who is “right fressh of . . . aray” (161) and “can of daunses

al the newe gise” (162), recalls Chaucer’s Squire: “Adieu al myrthe, adieu

now al solace / Adieu my ladies som-tyme so fresshe of face / Adieu beaute

that lastith but short space” (251 – 53). Many other figures are presented sym-

pathetically rather than satirically, especially as the Daunce moves down the

social scale. The laborer describes his difficult but honest life:

In wynde & reyn & gon forth at the plouh

With spade & Picoys laboured for my prouh

Dovyn & dikid & atte cart goon

For I may seyn & pleynly avow

In this world here rest is ther noon. (524 – 28)

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 297

With its positive and negative portraits, the Daunce works to instantiate nor-

mative social categories, on the one hand describing idealized estate identi-

ties and, on the other, correcting through satire any deviation from appro-

priate behavior.

What differentiates the Daunce of Poulys from other estates litera-

ture, however, is its presentation of the penitential discourse of “learning

to die” as the means to shape individual behavior and ensure social stabil-

ity. Here, besides heralding Death’s erasure of all earthly hierarchies in the

next world, the ars moriendi also offers a solution to social transgression or

sociopolitical disorder in this life. Death reminds the Astronomer that it is

Christianity that knows the origin of death, not “sentence of reson”:

Sith of Adam al the genealogie

Maade first of god to walke vpon the grounde

Deth doth arrest thus seith theologie

And alle shul deie for an appyll rounde. (383, 373 – 76)

Similarly, Christianity knows the remedy for death: the avoidance of sins of

body and mind, the practice of virtue, as well as regular confession, obser-

vance of which will allow the Christian to die without fear. The characters

in the Daunce initially express horror at Death’s invitation but, for the most

part, quickly move to acceptance, voicing proverbial memento mori wisdom

about the need to live well, avoid sin, and have death daily in mind, as they

take their own death’s hand and join the dance. The Abbess, chastened for

her soft living, ruefully reminds the reader of death’s unpredictability; and

the King, immediately upon Death’s invitation, sees “ful cleerly in sub

staunce / What pride is worth force or hih parage”(107–12). Most elabo-

rately, the Woman Sworn Chaste provides her audience with a full spiritual

program those who would make a good death should follow:

It helpith nat to stryve a-geyn nature

Namely whan death bi-gynneth tassaile

Wher-fore I counseil euery creature

To been redy a-geyn this fel batayle

Vertu is sewrer than othir plate or maile

Also no thyng may helpe more at sich a nede

Than to provide a sur acquytaile

With the hand of almesse to love god & drede. (313 – 20)

298 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

The series of thirty-four surprised but immediately repentant sinners are a

“myrrour” the reader can keep “Before your mynde aboven al thyng / To all

estatis a trew resemblaunce / That wormes foode is ende of your lyvyng”

(565 – 68). In presenting these lessons on how to die well, the poem carries

out its obvious didactic function.

It is noteworthy that the Daunce focuses on a very particular strand

of late medieval ars moriendi discourse, making “dying well” mainly into a

matter of self-mortification. This emphasis is most evident in the portraits

of professional religious, where the good death is presented as the logical

extension of the ascetic life, a life lived symbolically “dead” to the world.

To Death’s invitation (“Yeve me your hand with chekis ded & pale / Causid

of watche & long abstynence” [521 – 22]) the monk of the Charterhouse,

for example, responds that, although man fears death “bi naturall mocion”

(332), he has no fear, since “Vnto this world I was ded ago ful longe / Bi

myn ordre & my profession” (329– 30). The Canon Regular voices the same

sentiment:

Whi shulde I grutche or disobeye

The thyng to which of verrey kyndly riht

Was I ordeyned & born for to deye

As in this world is ordeyned euery wiht. (281 – 84)

This connection between the good death and asceticism points to the way

in which mortification of the self — in its standard lay articulation involv-

ing the avoidance of sins of body and mind, moderation in diet and dress,

the practice of virtue, as well as regular confession — is a form of self-

governance, an internalization of an external set of laws and overall ordering

of society. As Kenneth Burke writes, “mortification is the exercising in one-

self of ‘virtue’; it is a systematic way of saying no to disorder, or obediently

saying yes to order.”32 In its dire performance of the universal need to live

abstemiously, the Daunce of Poulys reaches toward a comprehensive descrip-

tion and correction of contemporary England. As Stow notes, it is “death

leading all estates, with the speeches of death, and answere of euerie state”

(1:109, my emphasis) — a measured dance of mortification that imagines and

seeks to stabilize England’s existing hierarchical social organization.

But the Daunce of Poulys does not serve only as an outlet for an

exemplary display of conservative civic pietism, as an example of the extent

to which, in the fifteenth century, powerful laymen like Carpenter and secu-

lar institutions such as the city felt fully capable of claiming a measure of

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 299

spiritual authority. The brilliance of the Daunce is how, in its poetic figu-

ration of the social real, it manages to represent a stable political commu-

nity through an image that is at once Christian and heterogeneous. As Emily

Steiner has recently noted, the notion of diversity in political bodies posed

somewhat of a challenge for medieval political juristic theory.33 For Aquinas,

for example, in his Aristotelian treatise De regimine principum or De Regno,

heterogeneity within political community is a necessity; indeed, the variety

of estates, trades, and social roles found in the city makes it the “perfect”

community. But this productive plurality must be gathered up into unity

through the governance of a single agent:

For if many men were to live together with each providing only

what is convenient for himself, the community would break up

into its various parts unless one of them had responsibility for the

good of the community as a whole, just as the body of a man and

of any other animal would fall apart if there were not some general

ruling force to sustain the body and secure the common good of

all its parts.

After all, “among the members of the body there is one ruling part, either

the heart or the head, which moves all the others,” and so “[i]t is fitting,

therefore, that in every multitude there should be some ruling principle.”34

Such a reading of Aristotle’s political philosophy through the organic meta-

phor of the body of 1 Corinthians 12:12 obviously naturalizes the system of

medieval sovereignty, offering as it does a moral justification for kingship, as

Ernst Kantorowicz’s classic study shows. Even the theological idea of Corpus

Christi, despite its explicit celebration of lay identity, was at least in part

intended to secure ecclesiastic hegemony, or, as Sarah Beckwith has argued,

to further “social integration and unity in the name of a single administering

body.”35

The city’s Daunce of Poulys monument, like Aquinas, implicitly cel-

ebrates diversity and celebrates the city as the perfect community through its

taxonomic rehearsal of estates and roles. What renders the Daunce at once

profoundly anti-Thomistic and particularly suitable as an imagination of the

political city-scape of London, however, is that each participant in the dance

must necessarily remain discrete, coming together temporarily to form, in a

civil fashion, a community organized along lateral, rather than vertical lines,

and in the process figuring what Wallace has called an “associational,” as

opposed to a hierarchic, ideology.36 As a product of civility, the image of the

300 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

dance is often evoked in the premodern period as a representation of sociopo-

litical harmony and peaceful urban community. A hundred years before the

Dance of Death motif appeared in Europe, Ambrogio Lorenzetti deployed

the image of the dance in his Buon governo frescoes in Siena, where a circle

of youths dancing the “tripudium, a solemnly festive dance,” symbolize, in

Quentin Skinner’s words, “the joy we naturally feel at the rule of justice and

the resulting attainment of peace” in a prosperous city-state.37 In 1531, less

than twenty years before the Daunce of Poulys was destroyed, Thomas Elyot

similarly described dance as both the practice and image of “the first morall

vertue called prudence” in his The Boke named the Governor, a text intended

to teach “one soveraigne governour” the proper rule of the “publike weale.”38

Lorenzetti and Elyot both invoke the secular, classical conception of dance

as a reflection on earth of the eternal and transcendent music of the spheres,

“the wonderfull and incomprehensible ordre of the celestiall bodies . . . and

their motions harmonicall.”39

The Daunce of Poulys has more often brought to mind for schol-

ars those other graveyard dancers, the mad, sacrilegious “Dancers of Col-

bek” whose grisly end Robert Mannyng details in Handlyng Synne. Yet the

Daunce is a decorous dance, which regularly emphasizes the first, formal

moment of the reverence — Death’s proffered hand and slight bow as he

invites his mortal partner to begin or join the dance with tags like “Lat see

your hand” (65, and 273) or “Yeve hidir thyn hand” (497, and 513) — and

clearly alludes to this secular iconographic tradition of the dance as an image

of social order and political harmony.40 But the dance on the walls of the

Pardon Churchyard also implicitly critiques this ancient idea that human

society reflects in some way the transcendent and eternal choral dance of the

planets. A dance of corpses and the dying, the Daunce of Poulys is emphati-

cally about time, using the human body in decay as a vivid expression of

temporality, fragmentation, and annihilation — of the truism that “undir

heuene in erthe is no thyng stable” (176).

In this way, then, Carpenter’s and Lydgate’s civic wall paintings

refurbish the classical choral dance as a Christian monument, emphasizing

the vanity and transience of earthly and individual human life — any par-

ticular person of any one estate — while evoking the dance as an image of

the enduring nature of the London polity as a whole. The threat of anarchy

posed by diversity in community so worrisome to Aquinas is countered by

the ars moriendi teaching of the Daunce: self-will is kept in check not by

a single governing figure (Death does not govern or even judge its mortal

victims and the king is simply one element in the heterogeneous totality),

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 301

but instead by demonstrating the proper internalization of Christian law in

forms of mortification. In the Daunce, the representatives from each estate,

by understanding that “Who livith a-ryght most nedis deye weel” (384),

learn to occupy their proper place in the community. Perversions of their

social roles through overreaching, indecorous ambition, or unchecked mate-

rial greed — those elements of individual desire that Aquinas identifies as

threatening to the integrity of the sociopolitical system as a whole if left

unchecked — are constructed as sins against God that lead to a second, eter-

nal death.

The Pardon Churchyard

Even though the arrangement of panels in the Daunce of Poulys processes

down the social order from emperor to hermit, the Daunce of Poulys is

physically situated so that the dancers move horizontally along one wall

to another, acting to map for the viewer, over and over again, the lesson

that natural law (Death’s “mortall lawe”) antedates and trumps the positive

law and customs undergirding social hierarchy. The power of the Dance of

Death in fifteenth-century Europe as a whole must have had much to do

with its juxtaposition of two universally acknowledged truths: the reality of

social hierarchy and the truth of corporeal and spiritual equality. But why

place this lesson inside the Pardon Churchyard? Why should the common

clerk have preferred this site for his commission to the more obvious site of

the charnel house facing into the more public space of St. Paul’s yard?

In use since the thirteenth century as a site for burial for the cathe-

dral canons, the Pardon Churchyard acquired its name sometime after the

Black Plague in 1348– 49, perhaps because it had been used for interment of

plague victims and had become associated with the idea that those buried

there, even if without proper ceremony, were granted indulgences for their

sins. Gilbert à Becket, father of Thomas, one of London’s patron saints, and

either sheriff or portgrave (i.e., mayor), was said to be buried in the church-

yard with his wife Anne. When Dean Thomas More enclosed the church-

yard within a cloister in the second decade of the fifteenth century, he rebuilt

the “faire chapell” dedicated to St. Anne and St. Thomas in its center, which

was believed to be the Becket mortuary. More’s renovation of the Becket

chapel and enclosure of the plot, setting it apart from the rest of Paul’s yard,

appears to have made it newly attractive for the city’s elite. Although St.

Paul’s in general was not a preferred burial choice of Londoners, the Pardon

Churchyard became a popular resting place for members of wealthy and

302 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

powerful lay families, as well as for deans and upper-level ecclesiastics.41 As

Stow reports in the sixteenth century, the churchyard had the reputation of

having “many persons, some of worship, and others of honour” buried there,

with monuments surpassing in richness those in the cathedral (1:327– 28).

But long before More’s renovations, the Pardon Churchyard was

also a significant site for London’s governors. For the Becket tomb, serving

as the destination of the mayoral processions recorded in the Liber Albus,

was a crucial element in the articulation of civic identity. According to Car-

penter’s account on October 28th, the day of the mayor’s election, the new

mayor would ride in procession to Westminster, where he would take his

oath at the Exchequer and be formally accepted in the king’s name by the

chancellor, treasurer, keeper of the Privy Seal, and barons of the Exchequer.

After returning to the city, and after feasting with aldermen and upper-

government officers at his residence, the mayor would process with them

from the Church of St. Thomas of Acon (i.e., Thomas à Becket) in Cheap-

side, to St. Paul’s. There they would first stand “between the two small

doors” in the nave, “to pray for the soul of Bishop William, who . . . obtained

from his lordship William the Conqueror great liberties for the City of Lon-

don.” Then they would process to the churchyard, “where lie the bodies of

the parents of Thomas, late Archbishop of Canterbury,” saying the De pro-

fundis for the repose of their souls, before returning to St. Thomas of Acon

and making an offering (Liber Albus, 24 – 25). Variations of this procession

concluded with a visitation of the Becket tomb in the Pardon Churchyard

on no fewer than seven other days of the year: Christmas, the Circumcision

(Jan. 1), Epiphany (Jan. 6), the Purification of the Virgin (Feb. 2), All Saints

(Nov. 1), and on the feasts of St. Stephen (Dec. 26) and St. John the Evan-

gelist (Dec. 27).42

These processions to the cathedral by the city’s governors have

obvious political value, working in ways similar to “beating of the bounds”

rogation ceremonies described by E. P. Thompson and Sarah Beckwith, and

Midsummer Watch processions described by Sheila Lindenbaum, where the

boundaries of the city are “ridden” by the mayor and civic elite to mark

the geographical limit of the city’s franchise.43 Carpenter records in detail

the complex expression of hierarchy encoded in the makeup and organi-

zation of the riding to Westminster and, especially, the procession to the

Pardon Churchyard, where “the commons preced[ed] on horseback in com-

panies, arrayed in the suits of their respective mysteries,” except for those “of

his livery” who processed just in front of the mayor:

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 303

No person, however, moved so close to the Mayor but that there

was a marked space between, while the serjeants-at-arms, the

mace-bearers, and his sword-bearer, went before him, with one

Sheriff on his right hand and the other on his left, bearing white

wands in their hands. The Recorder and the other Aldermen

followed next in order, and accompanied him through the middle

of the market of Westchepe to his house. (Liber Albus, 23)

Ordered in this ritualistic way, the mayor’s evening riding through the city,

into the nave of St. Paul’s, through to the Pardon Churchyard, then back out

to Chepestreet by way of the cathedral churchyard, makes several ideologi-

cally significant moves at once.

Thomas à Becket was the most important saint whom London

could claim as its own through birth. Even though his shrine was in Can-

terbury, his father was in his own right a successful citizen of London and

civic governor. The ritualized visits to the Becket tomb by the city’s govern-

ing elite are, in one respect, a tacit gesture toward civil self-governance in

relation to the Crown, one that counterbalances the city’s earlier submis-

sion of the new mayor for royal approval at the Exchequer. In this context,

the city appropriates the “triumph of the Western Church over a king of

England” represented by Becket and his cult.44 But claiming the Becket

family as champions of specifically lay, civic liberties in this particular space

was also crucial, as conflict between St. Paul’s and the city regarding land

use and access to the yard was an old problem, especially regarding issues of

enclosure of property once held common. The folkmoot was unable to meet

in St. Paul’s Yard from the 1320s on, because “Edward I allowed St Paul’s

cathedral to enclose it, to convert public space to the uses of a quasi-private

ecclesiastical corporation”; while just after Carpenter’s death, in the 1440s,

the city was powerless to prevent the dean and chapter from replacing a

gate to the west of the cathedral with a set of bars and a cross, controlling

the London laity’s access to the precinct from Bowyer Row (now Ludgate

Hill).45 The mayor’s procession, in entering into the cathedral and partici-

pating in traditional religious observances, thus at once sacralizes the mayor-

alty in its embodiment in the newly appointed mayor and extends the liberty

of the city into ecclesiastical territory, insisting on the city’s claim to rights of

way within the precinct walls.

Considered in the context of such ongoing quarrels, Dean More’s

enclosure of the Pardon Churchyard in the 1420s obviously called for some

response from London’s governors. More’s building project incorporated a

304 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

space with ambiguous boundaries — open to multiple cultural uses, bor-

dered by a major city access point to the precinct, and of symbolic impor-

tance to the city’s governors — into part of the cathedral proper, turning it

into unequivocally ecclesiastical territory. Carpenter’s response, acting as the

city’s representative, was to make the civic a part of this process of enclosure,

both in the simple sense that the Daunce of Poulys was a specifically civic

contribution to the Pardon Churchyard complex, and in the more subtle one

that the Daunce, running all around the churchyard on the back wall of the

new cloister, literally limned the church’s territorial claims. It did so, more-

over, with images that reminded viewers in general of the complex and mul-

tiple nature of English culture and, in particular, of the place of the courtly

and ecclesiastical within a larger web of authority structures, structures that

of course included the city government. By alluding to the earlier history of

the Pardon Churchyard as an open space associated, before its enclosure by

the dean, with the burial of people of different estates, and with common

burial during times of crisis, the Daunce allows the newly built cloister to

retain at least the image of its former social openness and inclusivity. It also

grounds that inclusivity in civic figures who appear on the walls as rela-

tive newcomers to the traditional “three estates” model of society that still

continued to dominate the French Danse Macabré, especially the London

panels’ Mayor and his Famulus.

The end of the Daunce

In 1549 — the eventful year of the introduction of the new Prayer Book, of

massive uprisings against it, and of the overthrow of the Duke of Somerset —

the Daunce of Poulys was destroyed. As John Stow reports:

In the yeare 1549 on the tenth of Aprill, the sayed Chappell, by

commaundment of the Duke of Sommerset, was begun to bee

pulled downe, with the whole Cloystrie, the daunce of Death, the

Tombes and Monuments: so that nothing thereof was left but the

bare plot of ground, which is since conuerted into a Garden, for

the pettie Canons. (1:327– 28)

Somerset’s demolition of the Daunce of Poulys can in part be understood as

yet another manifestation of the “flamboyant egocentricity of his rule” and

propensity for “playing the Renaissance prince,” since the cloister’s stone was

needed to build the Protector’s sumptuous new palace.46

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 305

Certainly it does not appear that the Daunce was targeted specif-

ically for doctrinal reasons.47 A Dance of Death in the Guildhall chapel

in Stratford, commissioned in imitation of the Daunce of Poulys by Hugh

Clopton (d. 1496) after his retirement as mayor of London, survived well

beyond the sixteenth century, even though wall paintings of other popular

devotional subjects (the Doom, the Virgin, St. Thomas à Becket, St. George)

were whitewashed in 1563 – 64 by John Shakespeare (the playwright’s father),

in obedience to the Royal Injunctions of 1559, which decreed all signs of

“idolatry” removed from places of worship.48 While Tottel’s inclusion of

Lydgate’s Daunce in the 1554 edition of the Fall of Princes may indeed be, as

Alexandra Gillespie has recently argued, the publisher’s attempt to capitalize

on the “religious conservatism” of Mary’s reign,49 a Dance of Death series

appears five years later as marginal decoration in A Book of Christian Prayers

(1559) by Richard Day, a translator of John Foxe’s Latin works and the son

of the “godly” printer of evangelical texts, John Day. Dedicated to Elizabeth

I and published early in her rule, Day judged the memento mori device an

appropriate decoration for the collection, which foregrounds the new doc-

trine of salvation by grace alone and encourages the queen toward further

reform. On the Continent, Hans Holbein’s rendition of the Dance of Death,

as Natalie Zemon Davis has demonstrated, was appropriated by Protestant

as well as Catholic printers to accompany polemical writings throughout

the first half of the sixteenth century.50 Doctrinally adaptable in itself, the

Daunce of Poulys was a casualty, rather, of the changed fortunes of the Par-

don Churchyard’s central monument, the tomb of Thomas à Becket’s par-

ents, which had been living on borrowed time since 1538, when Henry VIII

had the saint’s Canterbury shrine dismantled, his feast day suppressed, and

launched a virulent anti-Becket campaign in London.51

Although its destruction was likely “collateral damage” from the

destruction of the Becket tomb, it does appear, however, that the Daunce of

Poulys had in important ways outlasted its particular political moment. By

1549, the celebrations marking the swearing in of the new mayor and the pro-

cession to St. Paul’s had changed their semiotic dramatically, now present-

ing with as much force as could be mustered the city as a unified body with

corporate powers, perhaps in response to the aggressive policies of Henry

VII and VIII. In the early part of the sixteenth century, London’s Court

of Aldermen lost its authority to approve guild ordinances to the Crown

(a right won and confirmed by Parliament in 1437, soon after the Daunce

of Poulys was installed). The court was forced to accept Henry VII’s nomi-

nees for sheriff (William Fitzwilliam in 1506) and mayor (Stephen Jenyns

306 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

in 1508), and it fought throughout the first half of the century to retain its

powers to appoint key city officers.52 The Daunce of Poulys was a public art

project that worked through the appropriation and strategic deployment of

an established vocabulary of devotion. Its political aesthetic of multiplicity

and temporality was perhaps too subtle a poetics to counter effectively the

jurisdictional challenges of the Tudor kings.

By the early sixteenth century, the London governors had learned to

express their rights of political autonomy in unambiguous terms: the domi-

nus maior had taken on the official title of “Lord Mayor,” and his inaugural

riding had become enormously elaborate and partially recast as an aristo-

cratic ceremony. According to the merchant-tailor Henry Machyn’s diary

of 1553, after returning from Westminster (no longer by land but by water,

on “a goodly fuyst [foist] trymmed with banars and guns”), the new mayor

processed through the city with a number of spectacular pageants:

furst wher ij tallmen bayreng ij gret stremars of the Marchand-

tayllers armes, then cam on [one] [with a] drume and a flutt

playng, and a-nodur with a gret fife all they in blue sylke, and then

cam ij grett wodyn [wildman or greenman] with ij grett clubes all

in grene, and with skwybes [squibs] bornyng . . . with gret berds

and syd here [sideburns] and ij targets a-pon ther bake . . . and

then cam xvj trumpeters blohyng.

A loud and colorful spectacle, the mayor’s riding here incorporates unam-

biguous symbols signifying the city’s corporate power: wicker-work “wild”

giants at once symbolizing the city as a corpus mysticum with a mayoral

“head” and alluding to the legendary sons of the daughters of Albion and

London’s mythic pre-Christian origins; fireworks and trumpets, fifes, and

drums cacophonously evoking the corporation’s military might; and sump-

tuous costumes and pageants displaying the community’s enviable wealth.

The new mayor’s riding continues the custom of visiting St. Paul’s cathedral;

after dinner, the new mayor and his men proceed, as before, to the choir of

St. Paul’s cathedral — no longer, it seems, to say a solemn De Profundis or

pray at the side of tombs but instead to make noise all over the building:

[A]nd after dener to Powlles, and all them that bare targets

dyd [bare] after stayfftorches, with all the trumpets and wettes

blowhyng thrugh Powlles, thrugh rondabowt the qwer and the

body of the chyrche blowhyng, and so home to my lord mere[’s]

howsse.53

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 307

The symbolics of the mayor’s inaugural procession have noticeably shifted:

instead of drawing on and deploying the symbolics of religious obser-

vance — thereby insisting that devotion belongs to the civic world as much

as to the ecclesiastic — the city governors here appropriate the bombast and

pageantry of the royal triumph or entry. By the 1550s, the mayor’s procession

had become an entirely secular ceremony, in part because “the Reforma-

tion [had] stripped away the religious ceremonies from civic life” and the

appropriation of devotional rhetoric for civic self-promotion no longer had

any political point or purchase;54 in part because, for the city, the real threat

to civic jurisdiction was now royal, not ecclesiastic, and the Tudors’ aggres-

sive expansion of monarchical power needed to be answered — with loudly

blowing trumpets — in symbolic kind.

The Dance of Death is often taken to be a timeless and universal articulation

of human submission to the reality of death. However, when one of the earli-

est instantiations of the motif, the Daunce of Poulys, is examined in detail,

what is startling is, rather, how topical and local is this particular mapping

of mortality. The wall paintings are Carpenter’s and the city’s response to

the building of a cloister and the refurbishment of a chapel — a response

whose skill lies in the way it is designed to work with, not against, the dean

of the cathedral’s enclosure of the Pardon Churchyard, cannily offering itself

as a supplement to that project while also insisting on the role and relevance

of the civic within the ecclesiastical precinct.

Indeed, the Daunce does something rather more than merely rescue

the city’s jurisdictional claim to a piece of the Pardon Churchyard. It places

the city — through its “secretary” Carpenter and his religious colleague, Lyd-

gate — at the very forefront of artistic and religious fashion, as the promoter

of a major new didactic art work done in the latest Parisian style and associ-

ated with the influential religious politician, Jean Gerson. This art work,

by the very nature of its form and genre, resists being read as elevating the

claims of any one authority structure over another. In fact, part of its inter-

est for the city’s governors is precisely the way the Daunce formally proceeds

horizontally along the wall, and how it is shaped around an aesthetic of

multiplicity and temporality. The Dance of Death here is an imagination of

the social real that belongs specifically to the late medieval city. The Daunce

of Poulys belongs to a London representing itself in idealized form as a place

where political office is short and not inherited, where, as the Famulus or

officer reminds his audience, “service is noon heritage” (464). It belongs to

a London where the mayor is formally only the temporary “best” of a group

308 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

of “goode folke,” where it is understood that the king and the pope die like

everyone else, and where diversity of estate and competition between differ-

ent interest groups is a fact of life. In the Daunce of Poulys, the city claims,

not simply a continuing right to the meanings associated with the Pardon

Churchyard, but to be the agents who shape how civic society sees and rep-

resents itself.

Notes

Versions of this study were presented at seminars organized by the Medieval Stud-

ies program at the University of Connecticut at Storrs and the English Department’s

Medieval Colloquium at Harvard University. I thank those at both venues who pro-

vided valuable feedback, especially David Benson, Bob Hasenfratz, Derek Pearsall,

James Simpson, Kathleen Tonry, and Nicholas Watson. I also thank Sophie Ooster-

wijk, Fiona Somerset, Ramie Targoff, and the anonymous reader for JMEMS for their

timely comments and suggestions.

1 Joelle Burnouf, “Towns and Rivers, River Towns: Environmental Archaeology and

the Archaeological Evaluation of Urban Activities and Trade,” given at the Medieval

Studies Seminar, Harvard University, April 2007, summarizing both the results of a

collaborative research project on the Loire Valley and a wider body of French work

on urban environments. Burnouf uses language drawn from the work of geographer

Michel Lussault, L’espace en action: De la dimension spatiale des politiques urbaines, 2

vols. (diss., Université François Rabelais, UFR Droit, Économie et Sciences Sociales,

Tours, 1996). For reflections on urban topography, see also Daniel Lord Smail, Imagi-

nary Cartographies: Possession and Identity in Late Medieval Marseilles (Ithaca, N.Y.:

Cornell University Press, 2000); and Paul Strohm, “Three London Itineraries: Aes-

thetic Purity and the Composing Process,” in his Theory and the Premodern Text

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 3 –19.

2 John Fitzherbert, Here begynneth a ryght frutefull mater: and hath to name the Boke

of Surueyeng and Improumetes, STC 11005 (London, 1523), sig. H1r – v. On Fitzher-

bert, see Andrew Gordon, “John Stow and the Surveying of the City,” in John Stow

(1525 –1605) and the Making of the English Past, ed. Ian Gadd and Alexandra Gillespie

(London: British Library, 2004), 84 – 87.

3 David Wallace, Chaucerian Polity: Absolutist Lineages and Associational Forms in

England and Italy (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1997), 157; Ardis But-

terfield, “Chaucer and the Detritus of the City,” in Chaucer and the City, ed. Butter-

field (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2006), 3 – 22, at 5, 10.

4 Ruth Evans, “The Production of Space in Chaucer’s London,” in Chaucer and the

City, ed. Butterfield, 41 – 56, at 56.

5 I quote, respectively, Marion Turner, “Greater London,” in ibid., 25 – 40, at 26 and

29; Turner, Chaucerian Conflict: Languages of Antagonism in Late Fourteenth-

Century London (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007); Ralph Hanna, London Literature,

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 309

1300–1380 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), xv; and Sheila Linden-

baum, “London Texts and Literate Practice,” Cambridge History of Medieval Eng-

lish Literature, ed. David Wallace (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999),

284 – 309, at 295.

6 Augustine, The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods (New York: Modern Library, 1993),

13.11.

7 Kenneth Burke, The Rhetoric of Religion (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 198.

8 John Stow, A Survey of London, ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, 2 vols. (1908; repr.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), 1:327. Further quotations are from this edition.

9 For the mural at the Holy Innocents, see James M. Clark, The Dance of Death in the

Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Glasgow: Jackson, 1950), 14 – 48; and, more recently,

on the cemetery’s “prominent part in the mythology of Parisian identity,” see Vanessa

Harding, The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500–1670 (Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press, 2002), 85 –118. On the circumstances surrounding Lydgate’s

time in Paris, see Derek Pearsall, John Lydgate (Charlottesville: University Press of Vir-

ginia, 1970), 166 – 69. On Lydgate’s poem, see James Simpson, The Oxford English Lit-

erary History, Volume 2, 1350–1547: Reform and Cultural Revolution (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2002), 50– 62; Derek Pearsall, “Signs of Life in Lydgate’s Danse

Macabre,” in Zeit, Tod, und Ewigkeit in der Renaissance Literatur, ed. James Hogg, 3

vols. (Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 1988), 3:58– 71; and Jane

Taylor, “Translation as Reception: La Danse Macabré,” in Shifts and Transpositions in

Medieval Narrative: A Festschrift for Dr. Elspeth Kennedy, ed. Karen Pratt (Cambridge:

D. S. Brewer, 1994), 181 – 92. On the Dance of Death in England, see Sophie Oost-

erwijk, “Of Corpses, Constables and Kings: The Danse Macabre in Late Medieval

and Renaissance Culture,” Journal of the British Archaeological Association 157 (2004):

61 – 90. On the motif more generally, see Clark, Dance of Death in the Middle Ages and

the Renaissance; Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (London: Brit-

ish Museum Press, 1996), 153 – 59; and Leonard P. Kurtz, The Dance of Death and the

Macabre Spirit in European Literature (New York: Gordon Press, 1975). All quotations

of the verse in the Daunce of Poulys, cited by line numbers, are from Florence Warren,

ed., The Dance of Death, Early English Text Society, o.s. 181 (Oxford: Oxford Univer-

sity Press, 1931), here 28 and 22, and are from London, British Library, Lansdowne MS

699 (the B version) unless designated “Ellesmere” (the A version).

10 Stow, Survey of London, 1:327; Harding, The Dead and the Living, 104.

11 Guyot Marchant, La Danse macabre: Reproduction en fac-similé de l’ édition de Guy

Marchant, Paris, 1486 (Paris: Editions des Quatre Chemins, 1925). On the relation

between text and image in Marchant’s edition, see David A. Fein, “Guyot March-

ant’s ‘Danse Macabre’: The Relationship Between Image and Text,” Mirator (August

2000): 1 –11, http://www.glossa.fi/mirator/index_en.html (2 Nov. 2007).

12 On the relation between the Continental and English traditions, see Oosterwijk,

“Of Corpses, Constables and Kings,” 67– 75. For the relation between the Inkoo and

Lübeck murals, see Cora Dietl, “Ein Abglanz Notkes? Der Totentanz von Inkoo im

hanseatischen Kontext,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 101.2 (2000): 145 – 58. I thank

Barbara Newman and Richard Kieckhefer for sharing images of the Inkoo danse

macabre.

310 Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies / 38.2 / 2008

13 Binski, Medieval Death, 156.

14 Simpson, Reform and Cultural Revolution, 54.

15 Harding, The Dead and the Living, 104.

16 Stow, Survey of London, 1:328.

17 As Sheila Lindenbaum notes, Carpenter was also “the only common clerk to be called

secretarius and the only one to become an MP” (“London Texts,” 294). On Carpen-

ter’s life and career, see Thomas Brewer, Memoir of the Life and Times of John Carpen-

ter (London, 1856); Wendy Scase, “Reginald Pecock, John Carpenter and John Colop’s

‘Common-Profit’ Books: Aspects of Book Ownership and Circulation in Fifteenth-

Century London,” Medium Aevum 61 (1992): 261 – 74; and F. Kloppenborg, “Danse

macabre de Londres: Le commanditaire et son cercle d’amis,” 11e Congrès Interna-

tional d’Études sur les Danses Macabres et l’Art Macabre en Général (Meslay-le-Grenet,

France: Assoc. “Danses Macabres d’Europe,” 2003), 9– 24. On Carpenter and the

Whittington foundations, see Amy Appleford, “The Good Death of Richard Whit-

tington,” in The Body in Medieval Culture, ed. Suzanne Akbari and Jill Ross (forth-

coming).

18 See Caroline Barron, The Medieval Guildhall of London (London: Corporation of

London, 1974), 33.

19 Brewer, Memoir of the Life and Times of John Carpenter, appendix 1 and 2, 142 – 43,

includes a translation of the will and a list of Carpenter’s book bequests.

20 Caroline Barron, London in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004),

306.

21 Scase, “Reginald Pecock, John Carpenter and John Colop’s ‘Common-Profit’ Books,”

261 – 74.

22 Horn, although the city’s chamberlain rather than its clerk, can be considered Car-

penter’s professional predecessor because “[t]he chamberlain’s responsibilities for the

city’s records came in the course” of the fifteenth century “to be shared with, and

then largely transferred to, the common clerk” (Barron, London in the Middle Ages,

181). On Liber Horn and Andrew Horn’s “self-inscription” as “civic hero,” see Hanna,

London Literature, 67– 79. On the organization and sources of the Liber Albus, see

William Kellaway, “John Carpenter’s Liber Albus,” Guildhall Studies in London His-

tory 3 (1978): 67– 84.

23 John Carpenter, Liber Albus: The White Book of the City of London, trans. Henry

Thomas Riley (London, 1861), 3; hereafter cited parenthetically in the text.

24 Ethan Knapp, The Bureaucratic Muse: Thomas Hoccleve and the Literature of Late

Medieval England (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001), 148;

Lindenbaum, “London Texts,” 295.

25 Derek Pearsall points out that the two men appear to have had “similar tastes”: Car-

penter’s library included “many of Lydgate’s favourite moral-encyclopaedic works,

such as the Secreta secretorum and Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum morale, as well as the

works of Alanus, . . . Richard of Bury’s Philobiblon and Petrarch’s De remediis utriu

sque Fortunae” (Lydgate, 171).

26 “King Henry’s Triumphal Entry” in The Minor Poems of John Lydgate, ed. Henry

Noble MacCracken, vol. 2, Early English Text Society, o.s. 192 (London: Humphrey

Milford, Oxford University Press, 1934), 630– 48; hereafter cited in the text by line

Appleford / Dance of Death in London 311

numbers. On Lydgate’s use of Carpenter’s prose account, see Henry N. MacCracken,

“King Henry’s Triumphal Entry into London: Lydgate’s Poem and Carpenter’s Let-

ter,” Archiv für das Studium der neuren Sprachen und Literaturen 126 (1911): 75 –102.

On the triumph as covertly insisting on the city’s rights and powers, see C. David

Benson, “Civic Lydgate: The Poet and London”; and Scott Morgan-Striker, “Propa-

ganda, Intentionality, and the Lancastrian Lydgate,” in John Lydgate: Poetry, Culture,

and Lancastrian England, ed. Larry Scanlon and James Simpson (Notre Dame, Ind.:

University of Notre Dame Press, 2006), 147– 68 and 98–128. On the entry of Henry

V, and the civic triumph more generally, see Gordon Kipling, Enter the King: Theatre,

Liturgy, and Ritual in the Medieval Civic Triumph (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998),

esp. 201 – 9.

27 For a sustained discussion of Lydgate’s topical and civic poetry, see Maura Nolan,

John Lydgate and the Making of Public Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2005).

28 The figure of the Sergeant-at-law is of particular interest in this context. By the fif-

teenth century, the serjeants-at-law were the “elite of the legal profession” and espe-