Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Tripartite Agreement

Caricato da

simran yadav0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

37 visualizzazioni3 pagineTitolo originale

tripartite agreement.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

37 visualizzazioni3 pagineTripartite Agreement

Caricato da

simran yadavCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 3

According to section 2(e) of Indian Contract Act,1872, "every promise and every set

ofpromises forming consideration for each other is an agreement. For example 'A'promises

to 'B' to sell his land for Rs 75,00,000/- and 'B' accepts to purchase for the said amount.

Here 'A' and 'B' entered into an agreement.

A contract is an agreement which is made between at least 2 people in

which both of them agree to perform an act or abstain from doing the act

in return for some consideration. Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act

has defined a contract as an agreement which is enforceable by law. Thus

when an agreement is not against the provisions of law it is a contract.

Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act,1872 defines acontract as

“

An agreement enforceable by law

”.

The word

“

agreement

”

has been defined inSection 2(e) of the Act as

“

every promise and every set of promises, forming consideration foreach other

.”

A contract to which The Central Government or a State Government is a party iscalled a

“

Government Contract

”.

Government contracts have been accorded Constitutional recognition. The Constitution,

underArticle 298 , clearly lays down that the executive power of the Union and of each state

extends to

“

the carrying on of any trade or business and to the acquisition, holding and disposal of

propertyand the making of contracts for any purpose

”.

The Constitution therefore, provides that agovernment may sue or be sued by its own name. A

similar provision is found in the Code ofCivil Procedure 1908 under Section 79.

Principles Underlying Government Contracts

Reasonableness, fairness

The principle of reasonableness and rationality which is legally as well as philosophically an essential element of equality or non-arbitrariness is

projected by Article 14 and it must characterize every State Action , whether it be under the authority of law or in exercise of executive power

without making of law. The state cannot , therefore , act arbitrarily in entering into relationship, contractual or otherwise with a third party, but

its action must conform to some standard or norm which is rational an non- discriminatory. The action of the Executive Government should be

informed with reason and should be free from arbitrariness.

It is indeed unthinkable that in a democracy governed by the rule of law the executive Government or any of its officers should possess

arbitrary power over the interests of the individual. Every action of the executive Government must be informed with reason and should be

free from arbitrariness. That is the very essence of the rule of law and its bare minimal requirement. And to the application of this principle it

makes no difference whether the exercise of the power involves affection of some right or denial of some privilege.

ll actions of the State and its instrumentality are bound to be fair and reasonable. The actions are liable to be tested on the touchstone of

Article 14 of the Constitution of India. The State and its instrumentality cannot be allowed to function in an arbitrary manner even in the matter

of entering into contracts. The decision of the State either in entering into the contract or refusing to enter into the contract must be fair and

reasonable. It cannot be allowed to pick and choose the persons and entrust the contract according to its whims and fancies. Like all its actions,

the action even in the contractual field is bound to be fair. It is settled law that the rights and obligations arising out of the contract after

entering into the same is regulated by terms and conditions of the contract itself.

The requirement of 'fairness' implies that even administrative authority must act in good faith; and without bias; apply its mind to all relevant

considerations and must not be swayed by irrelevant considerations; must not act arbitrarily or capriciously and must not come to a conclusion

which is perverse or is such that no reasonable body of persons properly informed could arrive at. The principle of reasonableness would be

applicable even in the matter of exercise of executive power without making law. It is settled principle of law that the court would strike down

an administrative action which violates any foregoing conditions.

The duty to act fairly is sought to be imported into the contract to modify and alter its terms and to create an obligation upon the State which is

not there in the contract. The Doctrine of fairness or the duty to act fairly and reasonably is a doctrine developed in the administrative law field

to ensure the Rule of Law and to prevent failure of justice where the action is administrative in nature. Just as principles of natural justice

ensure fair decision where the function is quasi-judicial, the doctrine of fairness is evolved to amend, alter or vary the express terms of the

contract between the parties. This is so, even if the contract is governed by statutory provisions.

In a democratic society governed by the rule of law, it is the duty of the State to do what is fair and just to the citizen and the State should not

seek to defeat the legitimate claim of the citizen by adopting a legalistic attitude but should do what fairness and justice demand.

Public Interest

Tate owned or public owned property is not to be dealt with at the absolute discretion of the executive. Certain percepts and principles have to

be observed. public interest is the paramount consideration. There may be situations where there are compelling reasons necessitating the

departure from the rule, but there the reasons for the departure must be rational and should not be suggestive of discrimination. Appearance

of public justice is as important as doing justice. Nothing should be done which gives an appearance of bias, jobbery or nepotism.

The consideration to weigh in allotting a public contract are and have to be different than in case of a private contract as it involves expenditure

from the public exchequer. The action of the public authorities thus have to be in conformity with the standards and norms which are not

arbitrary, irrational or unreasonable. And whenever the authority departs from such standard or norms, the Courts intervene to uphold and

safeguard the equality clause as enshrined in Article 14 of the Constitution and strike down actions which are found arbitrary, unreasonable

and unfair and prone to cause a loss to the public exchequer and injury to public interest. Therefore, even when an award of contract may not

be causing any loss to the public exchequer manifestly, it may still be liable to quashment for being unfair, unreasonable, discriminatory and

violative of the guarantee contained in Article 14.

Equality, non-arbitrariness

From a positivistic point of view, equality is antithetic to arbitrariness. In fact, equality and arbitrariness are sworn enemies; one belonging to

the rule of law in a republic, while the other, to the whim and caprice of an absolute monarch. Where an act is arbitrary, it is implicit in it that it

is unequal both according to political logic and constitutional law and is violative of Article 14. the principle of reasonableness, which legally as

well as philosophically, is an essential element of equality or non-arbitrariness pervades Article 14 like a brooding omni-presence and the

procedure contemplated by Article 21 must answer the test of reasonableness in order to be in conformity with Article 14.

Contractual Liability

Article 299(2) immunizes the President, or the Governor, or the person executing any contract on his behalf, from any personal liability in

respect of any contract executed for the purposes of the Constitution, or for the purposes of any enactment relating to Government of India in

force. This immunity is purely personal and does not immunize the government, as such, from a contractual liability arising under a contract

which fulfills the requirements under Article 299(1).

The governmental liability is practically the same as that of a private person, subject, of course, to any contract to the contrary.

In order to protect the innocent parties, the courts have held that if government derives any benefit under an agreement not fulfilling the

requisites of Article 299(1), the Government may be held liable to compensate the other contracting party the Act, on the basis of quasi-

contractual liabilities, to the extent of the benefit received. The reason is that it is not just and equitable for the government to retain any

benefit it has received under an agreement which does not bind it. Article 299(1) is not nullified if compensation is allowed to the plaintiffs for

work actually done or services rendered on a reasonable basis and not on the basis of the terms of the contract.

three conditions namely:

1. a person should lawfully do something for another person or deliver something to him;

2. in doing so, he must not intend to act gratuitously; and

3. the other person for whom something is done or to whom something is delivered must enjoy the benefit thereof.

The Courts have adopted this view on practicable considerations. Modern government is a vast organization. Officers have to enter into a

variety of petty contracts, many a time orally or through correspondence without strictly complying to the provisions under Article 299. In such

a case, if what has been done is for the benefit of the government for its use and enjoyment, and is otherwise legitimate and proper, the Act

should step in and support a claim for compensation made by the contracting parties notwithstanding the fact that the contract in question has

not been made as per the requirements of Article 299.If it was to be held in applicable, it would lead to extremely unreasonable circumstances

and may even hamper the working of government. Like ordinary citizens even the government should be subject to the provisions .

Similarly, if under a contract with a government, a person has obtained any benefit, he can be sued for the dues of the Act though the contract

did not confirm to Article 299. if the Government has made any void contracts it can recover the same of the Act.

It needs to be emphasized that , Contract Act, does not deal with the rights and liabilities of parties accruing from that from relations which

resemble those created by contracts. Thus, in cases falling , the person doing something for another cannot sue for specific performance of the

contract nor can he ask for damages for breach of the contract for a simple reason that no valid contract exists between the parties. All that is

that if the goods delivered are accepted, or the work done is voluntarily enjoyed, then the liability to enjoy compensation for the said work or

goods arises. where a person does a thing not intending to act gratuitously and the other enjoys it.

in no way detracts from the binding character of Article 299(1) . The cause of action for the respondent's claim is not any breach of contract by

the government. In fact, the claim is based on the assumption that the contract in pursuance of which the respondent has supplied the goods,

or made the construction in question, is ineffective and, as such, amounts to no contract at all. Thus, does not nullify Article 299(1). In fact, may

be treated as supplementing the provisions under Article 299(1).What prevents is unjust enrichment and it as much to individuals as to

corporations and governments.

What Are Standard Form Contracts

Standard Form Contracts are agreements that employ standardized, non-negotiated provisions, usually in preprinted forms. These are

sometimes referred to as “boilerplate contracts,” "contracts of adhesion," or "take it or leave it" contracts. The terms, often portrayed in fine

print, are drafted by or on behalf of one party to the transaction – the party with superior bargaining power who routinely engages in such

transactions. With few exceptions, the terms are not negotiable by the consumer.

Standard form, business-to-consumer contracts fulfill an important efficiency role in the mass distribution of goods and services. These

contracts have the potential to reduce transaction costs by eliminating the need to negotiate the many details of a contract for each instance a

product is sold or a service is used. However, these contracts also have the ability to trick or abuse consumers because of the unequal

bargaining power between the parties. For example, where a standard form contract is entered into between an ordinary consumer and the

salesperson of a multinational corporation, the consumer typically is in no position to negotiate the standard terms; indeed, the company’s

representative often does not have the authority to alter the terms, even if either side to the transaction were capable of understanding all the

terms in the fine print. These contracts are typically drafted by corporate lawyers far away from where the underlying consumer and vendor

transaction takes place.

The danger of accepting unfair or unconscionable terms is greatest where these artful drafters of such contracts present consumers with

attractive terms on the visible or “shopped” terms of most interest to consumers, such as price and quality, but then slip one-sided terms

benefiting the seller into the less visible, fine print clauses least likely to be read or understood by consumers. In many cases, the consumer

may not even see these contracts until the transaction has occured. In some cases, the seller knows and takes advantage of the knowledge that

consumers will not read or make decisions on these unfair terms.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- C.P. 397 2022Documento4 pagineC.P. 397 2022Sadaqat YarNessuna valutazione finora

- No One Has Ever Been A US Citizen by Law of Statute PDFDocumento8 pagineNo One Has Ever Been A US Citizen by Law of Statute PDFkinnsbruckNessuna valutazione finora

- Right To Privacy and Data Protection Law PDFDocumento8 pagineRight To Privacy and Data Protection Law PDFMAHANTESH GNessuna valutazione finora

- Fairbank Goldman CHINA-A New HistoryDocumento581 pagineFairbank Goldman CHINA-A New HistoryAce100% (2)

- COC Checklist FormDocumento1 paginaCOC Checklist Formfuel stationNessuna valutazione finora

- PhilosophyDocumento51 paginePhilosophykenNessuna valutazione finora

- Transcript OP HearingDocumento71 pagineTranscript OP HearingDomestic Violence by ProxyNessuna valutazione finora

- Andrew Jackson DBQ 7thDocumento8 pagineAndrew Jackson DBQ 7thZul NorinNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016-Annual Performance Report V-IIDocumento197 pagine2016-Annual Performance Report V-IIMacro Fiscal Performance100% (1)

- Shtit June 2010 No 10Documento60 pagineShtit June 2010 No 10balkanmonitorNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaibhav Steel Corporation W.P.1735 of 2013 Dt.26.11.2013Documento7 pagineVaibhav Steel Corporation W.P.1735 of 2013 Dt.26.11.2013sweetuhemuNessuna valutazione finora

- BARANGAY CERTIFICATIONS & CLEARANCESDocumento6 pagineBARANGAY CERTIFICATIONS & CLEARANCESMichael MontoyaNessuna valutazione finora

- PA Law Grants Promotions in Rank To Terrorist Prisoners From PA Security ServicesDocumento4 paginePA Law Grants Promotions in Rank To Terrorist Prisoners From PA Security ServicesKokoy JimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Saraswathy Rajamani || Woman Who Fooled British by Dressing as ManDocumento11 pagineSaraswathy Rajamani || Woman Who Fooled British by Dressing as Manbasutk2055Nessuna valutazione finora

- 4th Session National Assembly SecretariatDocumento16 pagine4th Session National Assembly SecretariatChoudhary Azhar YounasNessuna valutazione finora

- A Fras I Abi IntellectualDocumento4 pagineA Fras I Abi IntellectualTim BowenNessuna valutazione finora

- Private and Public Sector Enterprises: ObjectivesDocumento12 paginePrivate and Public Sector Enterprises: ObjectivesSanta GlenmarkNessuna valutazione finora

- State-Sponsored Forced Labor: Comparing Cases of Uzbekistan and North KoreaDocumento9 pagineState-Sponsored Forced Labor: Comparing Cases of Uzbekistan and North KoreaDG YntisoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Doctrine of EclipseDocumento12 pagineThe Doctrine of EclipseKanika Srivastava33% (3)

- PART II SyllabusDocumento4 paginePART II SyllabusYanilyAnnVldzNessuna valutazione finora

- Application For Intimation and Transfer of Ownership of A Motor VehicleDocumento3 pagineApplication For Intimation and Transfer of Ownership of A Motor VehicleAnanth KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- HT Chandigarh - (2019-08-17)Documento68 pagineHT Chandigarh - (2019-08-17)Mohd AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- (WMW) Misaalefua v. United States Postal Service - Document No. 4Documento5 pagine(WMW) Misaalefua v. United States Postal Service - Document No. 4Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Stalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)Documento5 pagineStalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)itzkani100% (2)

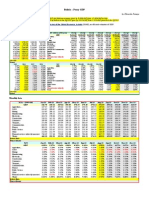

- Bolivia - Proxy GDPDocumento1 paginaBolivia - Proxy GDPEduardo PetazzeNessuna valutazione finora

- VU Special Consideration FormDocumento5 pagineVU Special Consideration FormEdin BekticNessuna valutazione finora

- Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood Cooperative and Sanlor Motors Corp. v. Kilusang Manggagawa NG LGS, Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood CooperativeDocumento14 pagineMagdala Multipurpose - Livelihood Cooperative and Sanlor Motors Corp. v. Kilusang Manggagawa NG LGS, Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood CooperativeAnnie Herrera-LimNessuna valutazione finora

- United Republic of Tanzania enDocumento102 pagineUnited Republic of Tanzania enAbbaa BiyyaaNessuna valutazione finora

- City of Manila Must Fulfill Land Donation ConditionDocumento3 pagineCity of Manila Must Fulfill Land Donation ConditionnurseibiangNessuna valutazione finora

- Board of Ed Agendas 2009 - 2010Documento9 pagineBoard of Ed Agendas 2009 - 2010Hob151219!Nessuna valutazione finora