Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Relationship Between Spontaneous Speech Function and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Profile in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pilot Case Study

Caricato da

hamba allahTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Relationship Between Spontaneous Speech Function and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Profile in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pilot Case Study

Caricato da

hamba allahCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Psychology, 2017, 8, 2138-2145

http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych

ISSN Online: 2152-7199

ISSN Print: 2152-7180

Relationship between Spontaneous Speech

Function and Behavior Rating Inventory of

Executive Function Profile in Children with

Autism Spectrum Disorders:

A Pilot Case Study

Kouji Oishi1*, Kunihiko Suto2, Asami Nakauchi3, Takatsugu Watanabe4,

Ami Takemori5, Maki Toyota1

1

College of Contemporary Psychology, Rikkyo University, Niiza, Japan

2

Faculty of Education, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan

3

Department of Early Childhood Education and Nursing, Seibi Gakuen College, Tokyo, Japan

4

Faculty of Social Welfare, Rissho University, Kumagaya, Japan

5

Tokorozawa City Education Center, Tokorozawa, Japan

How to cite this paper: Oishi, K., Suto, K., Abstract

Nakauchi, A., Watanabe, T., Takemori, A.,

& Toyota, M. (2017). Relationship between Background: Response inhibition and attentional flexibility are impaired in

Spontaneous Speech Function and Beha- individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). We descriptively analyzed

vior Rating Inventory of Executive Func-

whether differences in the functions of spontaneous speech derived from An-

tion Profile in Children with Autism Spec-

trum Disorders: A Pilot Case Study. Psy-

tecedent-Behavior-Consequence (A-B-C) analysis are related to the T-scores

chology, 8, 2138-2145. for response inhibition (“Inhibit”) and attentional flexibility (“Shift”) of the

https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2017.813136 Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) profiles of children

with ASD. Methods: Three children with ASD participated in this pilot case

Received: October 11, 2017

Accepted: November 19, 2017

study. The BRIEF was used as a measure of executive function (EF). Sponta-

Published: November 22, 2017 neous speech of all participants was recorded and classified into five catego-

ries: antecedent control of self (ACS), consequent control of self (CCS), ante-

Copyright © 2017 by authors and

cedent control of others (ACO), consequent control of others (CCO), and ex-

Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative

ception (EXP). Results: The T-score for “Shift” of all participants exceeded a

Commons Attribution International previously defined cut-off value. Spontaneous speech associated with “control

License (CC BY 4.0). of self” was not observed in any participant, while that associated with “con-

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

trol of others” varied among individuals. The participant with the highest

Open Access

frequency of spontaneous speech had the lowest “Shift” T-score, while the

participant with the least active spontaneous speech had the highest “Shift”

T-score. Conclusions: Our results suggest a potential association between

spontaneous speech and a shift in executive function in children with ASD.

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 Nov. 22, 2017 2138 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

Keywords

Autism Spectrum Disorders, Spontaneous Speech, Behavior Rating

Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), Attentional Flexibility,

Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (A-B-C) Analysis

1. Introduction

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) exhibit deficits in social com-

munication and restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Asso-

ciation, 2013; de Vries & Geurts, 2015). Indeed, routines, rituals, and repetitive

patterns of behavior are among the core symptoms of ASD. Mostert-Kerckhoffs

et al. (2015) suggested that response inhibition and attentional flexibility were

particularly impaired in individuals with ASD. They employed a visual Stroop

test in 66 individuals with ASD and found that they had slower verbal responses

than 56 individuals without ASD. Individuals with ASD required more reaction

time to perform stop and change responses to stimuli.

Various tests can be used to evaluate executive function (EF) deficits in child-

ren with ASD (Blijd-Hoogewys, Bezemer, & van Geert, 2014). The Behavior

Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) is a widely used behavioral rat-

ing scale measure. It assesses how a child performs in complex, unstructured

everyday problem-solving situations (Blijd-Hoogewys, Bezemer, & van Geert,

2014), indicates areas of weakness, and recommends that a clinician assess the

clinical severity of the deficits (Gioia, Isquith, Guy, & Kenworthy, 2000). In a

different approach to evaluate EF, Tarbox et al. (2011) taught children with aut-

ism to respond to simple rules of “if/then” antecedent-behavior conditions, and

observed a varied profile of responses. For this intervention to be successful,

verbal ability must be associated with executive function (Begeer, Wierda,

Scheeren, Teunisse, Koot, & Geurts, 2014). In their verbal fluency test in 26

children and adolescents with ASD, for example, Begeer et al. (2014) used the

number of words freely recalled by the participants as a measure of cognitive

flexibility. However, the relationship between executive function in everyday life

according to BRIEF and verbal ability has not been investigated (Semrud-Clikeman,

Fine, & Bledsoe, 2014), and it is unclear whether differences in the functions of

spontaneous speech used by children with ASD are related to response inhibi-

tion and attentional flexibility.

The function of spontaneous speech can be estimated by using by Antece-

dent-Behavior-Consequence (A-B-C) analysis. The ability of response inhibition

and attentional flexibility in children with ASD can be measured by BRIEF score.

In this brief report, we aimed to descriptively analyze whether differences in the

function of spontaneous speech derived by Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence

(A-B-C) analysis were related to the T-scores for response inhibition and atten-

tional flexibility, according to BRIEF, in children with ASD.

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2139 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

One girl (Yuri, 6th grade) and two boys (Tomo, 5th grade and Hika, 3rd grade)

were recruited by the second author. Their teacher had referred all three stu-

dents for participation because they had difficulty controlling their behavior in

the classroom without prompting from adults. They were all diagnosed with

ASD (Yuri) or broader autism phenotype (Tomo and Hika) by a mental health

professional (psychiatrist). In addition, the school’s homeroom teacher informed

us that Tomo and Hika exhibited prominent symptoms of emotional distur-

bance. Apart from information on her low overall activity level and slow physi-

cal movement, we had no additional information on Yuri. And there were no

information of psychometric test score for them.

The procedures used here were reviewed and judged to comply with ethical

standards by the Ethical Review Board of the College of Contemporary Psychol-

ogy, Rikkyo University (#17-01).

2.2. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

EF was assessed using the BRIEF Teacher Form (Gioia et al., 2000). We scored

responses according to the BRIEF manual, and calculated the T-score for eight

subcategories: Inhibit, Shift, Emotional control, Initiate, Working memory,

Plan/organize, Organization of materials, and Monitor. These subcategories are

clinical scales that comprise two broader indexes, the Behavioral Regulation In-

dex (BRI) and Metacognition Index (MI) (Gioia et al., 2000). Blijd-Hoogewys et

al. (2014) reported that children with ASD show high “Inhibit” and “Shift” res-

ponses in their BRI profiles. We therefore focused on the “Inhibit” and “Shift”

subcategories of BRIEF in the three participants.

2.3. Analysis of Spontaneous Speech

We examined the influence of spontaneous speech in children with ASD on the

behaviors of themselves and others. The spontaneous speech of all participants

was analyzed according the A-B-C format, where “A” refers to the antecedent, or

the event or activity that immediately precedes a behavior; “B” refers to the ob-

served behavior; and “C” refers to the consequence, or the event that imme-

diately follows a response. Observations of spontaneous speech were conducted

using the event sampling method (Barlow & Hersen, 1984). Functions of spon-

taneous speech (frequency per minute) were classified according to five catego-

ries: antecedent control of self (ACS), consequent control of self (CCS), antece-

dent control of others (ACO), consequent control of others (CCO), and excep-

tion (EXP). Individuals with ASD who exhibit high levels of spontaneous speech

associated with “control of self” may show a change in response inhibition

and attentional flexibility (Mostert-Kerckhoffs, Staal, Houben, & de Jonge,

2015).

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2140 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

2.4. Procedures

Interpersonal interactions between the participants and their classmates during

school recess were recorded on video, and spontaneous speech behaviors were

analyzed according to the A-B-C format. The recorded observations lasted for 5

to 22 minutes and were collected twice for each participant at an interval of one

month. The first author and research colleagues (two undergraduate students)

independently scored the behaviors. Interobserver agreement for the recorded spon-

taneous speech behaviors among the participants was 86.7% (range 75.0% - 100%). If

the frequency per minute of the control of self (CS) is high, there is a possibility of a

change in response inhibition and attentional flexibility (in the BRIEF score)

pointed out by individuals with ASD (Mostert-Kerckhoffs et al., 2015).

3. Results

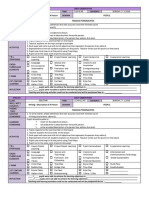

The BRIEF profiles of the participants are shown in Figure 1. All participants

showed a divergence with the typical profile of children with ASD reported by

Blijd-Hoogewys et al. (2014). Additionally, individual differences in profiles

were seen among the participants. In Yuri’s profile, the T-score for the “Shift”

(T-score = 77) and “Initiate” (T-score = 77) subcategories exceeded the cut-off

value reported by Blijd-Hoogewys et al. (2014). In Tomo’s profile, the T-score

for the “Inhibit” (T-score = 69), “Shift” (T-score = 74), “Emotional control”

(T-score = 81), “Initiate” (T-score = 69), and “Monitor” (T-score = 71) subcate-

gories exceeded the cut-off value. In Hika’s profile, the T-score for the “Inhibit”

(T-score = 73), “Shift” (T-score = 68), “Emotional control” (T-score = 81),

“Working memory” (T-score = 74), “Plan/organize” (T-score = 72), and “Moni-

BRI = Behavioral Regulation Index; MI = Metacognition Index; ASD = Typical profile of children

with ASD (Blijd-Hoogewys et al., 2014).

Figure 1. BRIEF profiles of the participants. Horizontal dashed line indicates the cut-off

T-score at 65.

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2141 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

ACS = Antecedent Control of Self; CCS = Consequent Control of Self; ACO = Antecedent Control of

Others; CCO = Consequent Control of Others; EXP = Exception

Figure 2. Spontaneous speech functions of the participants: (a) Yuri; (b) Tomo; (c) Hika.

tor” (T-score = 71) subcategories exceeded the cut-off value. The T-score for

“Shift” exceeded the cut-off value by a similar amount for all participants.

The spontaneous speech functions of the participants are shown in Figure 2.

None of the participants exhibited spontaneous speech associated with the func-

tion of “control of self”. In contrast, spontaneous speech associated with the

function of “control of others” was seen in all participants, but its frequency dif-

fered markedly. Yuri showed low frequency of spontaneous speech associated

with ACO (0.74/min). Tomo also only exhibited spontaneous speech associated

with ACO (trial 1: 1.28/min, trial 2: 0.72/min) but at a slightly higher frequency

than Yuri. Hika exhibited spontaneous speech associated with both ACO (trail 1:

6.90/min, trial 2: 2.89/min) and CCO (trial 1: 1.91/min, trial 2: 0.24/min) with

high frequency.

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2142 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

Yuri exhibited the lowest frequency of spontaneous speech but the highest

“Shift” T-score among the three participants. Tomo exhibited more spontaneous

speech than Yuri, but had a lower “Shift” T-score. On the other hand, Hika

showed hyperactivity, exhibiting the most frequent spontaneous speech, the lowest

“Shift” T-score, and highest “Inhibit” T-score among the three participants.

4. Discussion

Our results suggest that the spontaneous speech of children with ASD may be

related to a shift in attentional flexibility among the subcategories of executive

function. Our results do not suggest an association between the spontaneous

speech of children with ASD and response inhibition. Spontaneous speech asso-

ciated with the function of “control of self” was not observed in any of the par-

ticipants. Moreover, among the “control of others” subcategories, spontaneous

speech associated with CCO was not observed in 2 of the 3 participants. The

participant with the highest frequency of spontaneous speech had the lowest

“Shift” T-score according to BRIEF, while the participant with the least active

spontaneous speech had the highest “Shift” T-score.

Our results are in agreement with previous findings. According to Begeer et

al. (2014), children with ASD produce errors in clustering and switching in a

verbal fluency task, suggesting that these features may be linked to cognitive

flexibility. Since shifts in executive function are one of the components com-

prising cognitive flexibility, it is possible that the language function (verbal flu-

ency) is related to this shift. On the other hand, our findings suggest that the

“Inhibit” subcategory of BRIEF is highly associated with overall activity level,

but its relationship with spontaneous speech is unclear. However, due to the li-

mited number of cases in the present study, further studies are required to clari-

fy these associations.

4.1. Implications

Our results suggest a potential association between spontaneous speech and

shifts in executive function. Inducing spontaneous speech associated with a

function of “control of self” may improve cognitive flexibility in children with

ASD. Findings by Tarbox et al. (2011) suggest that behavioral training, by gene-

rating a verbal scenario using “if/then” conditions, can be used to improve a

person’s flexibility with respect to how they deal with various situations. This

technique enhances self-control of behavior using rule-governed behavior (RGB)

training. More research with a larger number of cases is needed to confirm these

findings.

The relationship between spontaneous speech and inhibition of executive

function is unclear. While an advantage of our study was that we examined par-

ticipants’ interpersonal interactions in the natural setting of school recess, we

were unable to control for participants’ activity levels. A more controlled setting

may allow for more detailed analysis and confirm whether differences in settings

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2143 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

affect the activities and behaviors of children with ASD. Future research should

confirm behaviors in clinical and experimental settings, including those with

conditionally controlled settings, activities, and behaviors.

4.2. Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Our results were obtained from only three cases;

therefore, larger scale studies are needed to clarify the relationship between

spontaneous speech and shifts in attentional flexibility. Previous studies have

shown a correlation between vocabulary and similarity scores in intelligence

tests (Begeer, Wierda, Scheeren, Teunisse, Koot, & Geurts, 2014). As we only

examined the relationship between spontaneous speech and executive function,

further research is required to investigate the relationship between other types of

speech and execution function. Moreover, we analyzed behaviors of spontaneous

speech across observation sessions ranging from 5 to 22 minutes; therefore, there

is a possibility that the differences observed among the participants may be at-

tributable to differences in observation time. We do not think that this is the

case, however, because the participants did not frequently exhibit a particular

reaction at specific times and those who expressed behaviors at high frequency

also exhibited the behavior throughout the observation period, and no differ-

ences in distribution were observed over time. To confirm this, future studies

should analyze behaviors across the same length of time.

5. Conclusion

Our results suggest that the spontaneous speech of children with ASD may be

related to a shift in attentional flexibility among the subcategories of executive

function. On the other hand, our findings suggest that the “Inhibit” subcategory

of BRIEF is highly associated with overall activity level, but its relationship with

spontaneous speech is unclear. Our results suggest that inducing spontaneous

speech associated with a function of “control of self” may improve cognitive

flexibility in children with ASD.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the children and their families, whose participation and col-

laboration made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP15K04253.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2144 Psychology

K. Oishi et al.

Disorders. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Barlow, D. H., & Hersen, M. (1984). Single Case Experimental Designs: Strategies for

Studying Behavior Change. London: Pergamon Press.

Begeer, S., Wierda, M., Scheeren, A. M., Teunisse, J. P., Koot, H. M., & Geurts, H. M.

(2014). Verbal Fluency in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Clustering and

Switching Strategies. Autism, 18, 1014-1018.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313500381

Blijd-Hoogewys, E. M., Bezemer, M. L., & van Geert, P. L. (2014). Executive Functioning

in Children with ASD: An Analysis of the BRIEF. Journal of Autism and Developmen-

tal Disorders, 44, 3089-3100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2176-9

de Vries, M., & Geurts, H. (2015). Influence of Autism Traits and Executive Functioning

on Quality of Life in Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2734-2743.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2438-1

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). Behavior Rating Inventory

of Executive Function. Luts, Florida: PAR.

Mostert-Kerckhoffs, M. A., Staal, W. G., Houben, R. H., & de Jonge, M. V. (2015). Stop

and Change: Inhibition and Flexibility Skills Are Related to Repetitive Behavior in

Children and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 45, 3148-3158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2473-y

Semrud-Clikeman, M., Fine, J. G., & Bledsoe, J. (2014). Comparison among Children

with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Nonverbal Learning Disorder and Typically Devel-

oping Children on Measures of Executive Functioning. Journal of Autism and Deve-

lopmental Disorders, 44, 331-342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1871-2

Tarbox, J., Zuckerman, C. K., Bishop, M. R., Olive, M. L., & O’Hora, D. P. (2011).

Rule-Governed Behavior: Teaching a Preliminary Repertoire of Rule-Following to

Children with Autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 125-139.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393096

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2017.813136 2145 Psychology

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Rancangan Pengajaran Harian: MasakanDocumento19 pagineRancangan Pengajaran Harian: MasakanAmy NoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Lesson Plan n6Documento6 pagineLesson Plan n6Șarban DoinițaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- 5 Stages of Reading ProcessDocumento1 pagina5 Stages of Reading ProcessSaleem RazaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Understanding IntersubjectivityDocumento19 pagineUnderstanding IntersubjectivityJohn Karl FernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Tiered LessonDocumento9 pagineTiered Lessonapi-372024462Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Mind Map Chapter 2Documento2 pagineMind Map Chapter 2Nagarajan MaradaiyeeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- JELLT - The Impact of Colors PDFDocumento15 pagineJELLT - The Impact of Colors PDFM Gidion MaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Syllabus (G5)Documento40 pagineSyllabus (G5)Shamin GhazaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Concepts of Teaching LearningDocumento7 pagineConcepts of Teaching LearningCherry CamplonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Plato's IdealismDocumento4 paginePlato's IdealismachillesrazorNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Mood Board Process Modeled and Understood As A Qualitative Design Research ToolDocumento28 pagineThe Mood Board Process Modeled and Understood As A Qualitative Design Research ToolLuisa Fernanda HernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Techniques in Technical WritingDocumento5 pagineBasic Techniques in Technical Writingdave vincin gironNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Knowledge and Cognitive Development in AdulthoodDocumento23 pagineKnowledge and Cognitive Development in AdulthoodEduardoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Fenix - Assingment 1 - Sec4Documento3 pagineFenix - Assingment 1 - Sec4Dei FenixNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Data Collection Methods for Grade 7Documento25 pagineData Collection Methods for Grade 7eliana tm31Nessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Idt-5000 Instructional Design PlanDocumento3 pagineIdt-5000 Instructional Design Planapi-336114649Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- A Buddhist Doctrine of Experience A New Translation and Interpretation of The Works of Vasubandhu The Yogacarin by Thomas A. Kochumuttom PDFDocumento314 pagineA Buddhist Doctrine of Experience A New Translation and Interpretation of The Works of Vasubandhu The Yogacarin by Thomas A. Kochumuttom PDFdean_anderson_2100% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- Critical Thinking Workbook NEWDocumento13 pagineCritical Thinking Workbook NEWPatricia Diaz Herrera82% (11)

- Animal Conciousnes Daniel DennettDocumento21 pagineAnimal Conciousnes Daniel DennettPhil sufiNessuna valutazione finora

- Service Learning ReflectionDocumento6 pagineService Learning ReflectionAshley Renee JordanNessuna valutazione finora

- Session Completion MessagesDocumento3 pagineSession Completion MessagesrajakrishnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kinds of EvidenceDocumento10 pagineKinds of EvidenceAbby Umali-Hernandez100% (1)

- 2 Major Theoretical Strands of Research MethodologyDocumento15 pagine2 Major Theoretical Strands of Research MethodologyAnand Dubey0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Daily Lesson Plan of ch11Documento1 paginaDaily Lesson Plan of ch11Ihsan ElahiNessuna valutazione finora

- Designing Assessment Tasks - Extensive Reading 2Documento9 pagineDesigning Assessment Tasks - Extensive Reading 2Farah NadiaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Authenticity InventoryDocumento75 pagineThe Authenticity Inventorybordian georgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Jest All in One Notes 2018-Final Updated PDFDocumento165 pagineJest All in One Notes 2018-Final Updated PDFXeno AliNessuna valutazione finora

- The Woodpecker MethodDocumento2 pagineThe Woodpecker MethodNicolas Riquelme100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Week 2Documento10 pagineLesson Plan Week 2NURUL NADIA BINTI AZAHERI -Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Effectiveness of Project - Based Learning (Egg Drop Project) Towards Students' Real World Connection in Learning PhysicsDocumento6 pagineThe Effectiveness of Project - Based Learning (Egg Drop Project) Towards Students' Real World Connection in Learning PhysicsinventionjournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)