Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Malnutrition in Children With Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)

Caricato da

irenaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Malnutrition in Children With Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)

Caricato da

irenaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

R E S E A R C H P A P E R S

Malnutrition in Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): Determinants

and Short-term Impact of Corrective Intervention

BALU VAIDYANATHAN, SREEPARVATHY B NAIR, KR SUNDARAM *, UMA K BABU, K SHIVAPRAKASHA**,

SURESH G RAO**, R KRISHNA KUMAR

From the Departments of Pediatric Cardiology, Biostatistics* and Pediatric Cardiac Surgery**, Amrita Institute

of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Elamakkara P.O., Kochi, Kerala 682 026, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Balu Vaidyanathan, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Amrita

Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Amrita Lane, Elamakkara, P.O. Kochi. Kerala 682 026, India.

E-mail: baluvaidyanathan@gmail.com

Manuscript received: October 20, 2006; Initial review completed: February 27, 2007;

Revision accepted: September 3, 2007.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To identify determinants of malnutrition in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) and

examine the short-term effects of corrective intervention. Methods: Patients with CHD admitted for

corrective intervention were evaluated for nutritional status before and 3 months after surgery. Detailed

anthropometry was performed and z-scores calculated. Malnutrition was defined as weight, height and

weight/height z-score ≤ –2. Determinants of malnutrition were entered into a multivariate logistic regression

analysis model. Results: 476 consecutive patients undergoing corrective intervention were included. There

were 16 deaths (3.4%; 13 in-hospital, 3 follow-up). The 3-month follow-up data of 358 (77.8%) of remaining

460 patients were analyzed. Predictors of malnutrition at presentation are as summarized: weight z-score ≤

–2 (59%): congestive heart failure (CHF), age at correction, lower birth weight and fat intake, previous

hospitalizations , ≥ 2 children; height z-score ≤ –2 (26.3%): small for gestation, lower maternal height and

fat intake, genetic syndromes; and weight/height z-score ≤ –2 (55.9%): CHF, age at correction, lower birth

weight and maternal weight, previous hospitalizations, religion (Hindu) and level of education of father.

Comparison of z-scores on 3-month follow-up showed a significant improvement from baseline, irrespective

of the cardiac diagnosis. Conclusions: Malnutrition is common in children with CHD. Corrective

intervention results in significant improvement in nutritional status on short-term follow-up.

Key words: Congenital heart disease, Corrective cardiac intervention, Malnutrition.

INTRODUCTION (CHF) and respiratory infections(13,14). This results

in a high prevalence of pre-operative malnutrition in

Malnutrition is a common cause of morbidity in patients with CHD(15). The implications of pre-

children with congenital heart disease (CHD)(1-6). operative malnutrition for future somatic growth are

Studies from developed countries have documented unknown and the role of different ethnic, socio-

normalization of somatic growth when corrective economic and cultural factors (very common in

surgery for CHD is performed early(7-12). In India) on the nutritional status of patients with CHD

developing countries, due to resource limitations, have not been hitherto studied.

corrective interventions for CHD are performed late,

leading to a vicious cycle of congestive heart failure We previously reported that pre-operative

Accompanying Editorial: Page 535

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 541 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

VAIDYANATHAN, et al. MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

malnutrition and respiratory infection do not impact height of parents were recorded and mid-parental

immediate outcomes after surgery for infants with height was estimated.

large VSD(15,16). However, on five year follow-up,

a significant proportion of these patients continued A nutritionist obtained a detailed dietary history

to have suboptimal growth compared to normal by interviewing the child’s mother using a 24-hour

population(17). This study reports the prevalence recall method. Dietary intake on a typical day’s diet

and determinants of malnutrition at presentation for at home was evaluated for 3 consecutive days;

corrective intervention in a large number of patients average intake was calculated. The relative

with various CHD and analyzes the impact of proportions of total calorie, protein, carbohydrate

correction on the nutritional status on short-term and fat intake were estimated by using standard

follow-up. charts of nutritive values of common dietary items.

Dietary intake of calories and proteins were

METHODS expressed as percentage of recommended daily

allowance for age and sex. Details of feeding like

This is a prospective study conducted in a tertiary breast feeding, age at weaning, type and adequacy of

referral hospital. All children <5 years undergoing weaning foods were recorded.

surgical or catheter-based corrective intervention at

our center from June 2005-June 2006 were included. Follow-up evaluations were scheduled at 3

Patients undergoing palliative procedures were months and then at 6 monthly intervals. Follow-up

excluded. evaluations included assessment of growth, dietary

intake and cardiac evaluation for any significant

A comprehensive evaluation of determinants of residual abnormalities. This report is limited to

malnutrition was performed at admission for analysis of 3-month follow-up.

corrective intervention. These included demo-

graphic, birth-related, cardiac, socio-economic and Malnutrition was defined as z-scores of <–2 for

cultural factors as well as feeding practices (Table I). weight (low weight-for-age), height (low height-for-

Socioeconomic status was graded using the modified age) and weight/height (low weight-for-height).

Kuppuswamy scale(18). z-scores of <–3 was classified as having severe

malnutrition(20).

All patients underwent an anthropometric

evaluation at presentation; z-scores for weight, To test the statistical significance of the

height and weight/height were calculated using association between nutritional status and risk

CDC-2000 reference values(19). The weight and variables, univariate analysis was done applying

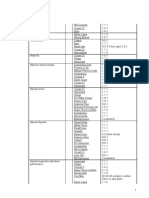

TABLE I DETERMINANTS OF MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE AT PRESENTATION

Demographic factors Age, sex, birth weight, order of birth; weight for gestational age (categorized as AGA,

SGA or LGA)

Cardiac and clinical factors Cardiac diagnosis and physiology; presence of congestive heart failure, pulmonary

hypertension; oxygen saturation; previous hospitalizations and presence of associated

genetic syndromes.

Socioeconomic factors Details of family - nuclear/joint, number of family members and children; religion,

consanguinity; age and level of education of parents; occupation of father, employment

status of mother and monthly income.

Growth potential Weight and height of parents and mid-parental height.

Dietary factors Intake of calories, protein, carbohydrate, fat (expressed as percentage of RDA);

breastfeeding, age at weaning, type of weaning foods and adequacy of weaning.

AGA – appropriate for gestational age, SGA – small for gestational age, LGA – large for gestational age, RDA – recommended

daily allowance.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 542 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

VAIDYANATHAN, et al. MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

Chi-square test (discrete variables) and independent TABLE II CARDIAC DIAGNOSES OF PATIENTS (N=476)

samples t-test (continuous variables). All variables INCLUDED IN THE STUDY

significant at 20% level (80% Confidence) were Cardiac diagnosis Number (%)

included in the stepwise multivariate logistic

regression analysis. Odds ratios with 95% Patent ductus arteriosus 118 (24.8)

confidence intervals and P values were computed for Ventricular septal defect 112 (23.5)

the statistically significant variables using standard Tetralogy of Fallot 63 (13.2)

formulae. Comparison of three-month follow up data Atrial septal defect 58 (12.2)

with baseline values was done using the paired ‘t’ D-transposition of great arteries 39 (8.2)

test. The study was approved by the review board of Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection 33 (6.9)

the Institution and the funding agency. Pulmonic stenosis 15 (3.2)

RESULTS Coarctation of aorta 12 (2.5)

Atrioventricular septal defect 11 (2.3)

476 consecutive patients undergoing corrective

Anomalous left coronary from pulmonary artery 5 (1.1)

intervention for CHD were included. Mean age was

Aortopulmonary window 3 (0.6)

15.2 ± 16.2 months. There were 296 (62.2%) infants

(≤1 year) and 45 (9.5%) neonates. 233 (48.9%) Truncus arteriosus 3 (0.6)

patients were male. The most common cardiac Aortic stenosis 2 (0.4)

diagnosis was left-right shunts (64.3%). Of 431 Coronary arteriovenous fistula 1 (0.2)

children older than 4 weeks of age, 320 were Congenital mitral regurgitation 1 (0.2)

acyanotic and 111 were cyanotic. 344 patients

(72.3%) underwent surgery while the remaining

saturation, dietary intake of calories, weaning

were catheter-based interventions. 194 patients

practices, type of family (nuclear vs joint),

(40.8%) had congestive heart failure. 30 (6.3%) had

consanguinity, age of parents and employment status

associated genetic syndromes. Table II lists the

of the mother did not influence the nutritional

cardiac diagnoses of patients included in the study.

status.

There were 16 deaths (3.4%; 13 in-hospital, 3 on The results of multivariate logistic regression

follow-up). Three-month follow-up data of 358 analysis of predictors of malnutrition are

survivors was analyzed. 59% (weight), 26.3% summarized in Table III.

(height) and 55.9% (weight/height) of patients had

z-scores of ≤ –2 at presentation, z-scores of ≤–3 for On 3-month follow-up, there was significant

weight, height and weight/height were observed in improvement of z-scores of all 3 parameters

27.7%, 10.1% and 24.2% patients, respectively. compared to baseline values (Fig. 1). There was no

On univariate analysis, age at intervention, lower

birthweight, previous hospitalizations, presence of

congestive heart failure and pulmonary hyper-

tension, education of parents, lower socio-economic

scale, parental anthropometry and lower fat intake

were associated with z-score ≤-2 for all three

parameters. Presence of associated genetic

syndrome was predictive of lower weight and height

z-score, small for gestation was associated with

Weight P<0.001

lower height and weight/height z-scores. While

Height P 0.04

presence of > 2 children in family was predictive of Weight/height

weight z-score ≤–2, religion (Hindus had lower Fig. 1. Comparison of z-scores at presentation (baseline)

values) had an impact on weight/height z-score. and 3-month follow-up (data of 358 patients

Factors like sex, cardiac diagnosis, oxygen analyzed).

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 543 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

VAIDYANATHAN, et al. MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

difference in the baseline characteristics between Hemodynamic factors (presence of CHF), older

patients with follow-up and those who have not yet age at corrective intervention and lower growth

completed the 3-month follow-up evaluation. potential (lower birth weight, small for gestation,

lower parental anthropometry and associated genetic

DISCUSSION

syndrome) emerged as significant predictors of

This study reports a very high prevalence of malnutrition at presentation on multivariate analysis

malnutrition at presentation in a large cohort of (Table III). Factors like sex, cardiac diagnosis,

patients with various CHD undergoing corrective dietary intake (except that of fat) and socio-

intervention. However, there was significant catch- economic scale had no significant impact on

up growth on 3-month follow-up (Fig. 1), suggesting nutritional status.

that correction of the cardiac anomaly favorably

influences the nutritional status. The adverse impact of CHF on growth has been

TABLE III MULTIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS OF PREDICTORS OF WEIGHT, HEIGHT AND WEIGHT/HEIGHT Z- SCORE < –2

Variable Odd’s ratio P value

(95 % CI)

Weight z-score <–2

Congestive heart failure 3.92 (1.86 -8.29) <0.001

Age at correction 6.1-12 months 6.31 (1.64-24.38) 0.008

12.1-24 months 8.62 (2.79-26.70) <0.001

Birth weight < 2.5 Kg 20.24 (6.15-66.56) <0.001

2.51-3 Kg 7.67 (2.59-22.68) <0.001

Previous hospitalizations 4.05 (1.55-10.64) 0.004

Fat intake <25g/day 10.31 (2.02-52.63) 0.005

25-50 g/day 4.22 (1.39-12.87) 0.011

Number of children ( >2) 2.05 (1.12-3.77) 0.021

Height z-score < –2

Small for gestational age 6.51 (2.97-14.26) <0.001

Height of mother (< 150 cm) 2.84 (1.27-6.37) 0.01

Fat intake (< 25 g/day) 3.46 (1.24-9.69) 0.02

Associated syndrome 3.02 (1.26-7.22) 0.013

Order of birth (> 3) 2.67 (1.22-5.81) 0.014

Weight/Height z-score < –2

Congestive heart failure 4.31 (2.41-7.74) <0.001

Age at correction 6.1-12 months 3.35 (1.56-7.20) 0.002

12.1-24 months 3.24 (1.47-7.13) 0.004

Birth weight < 2.5 Kg 4.25 (1.77-10.20) 0.001

2.51-3Kg 2.53 (1.07-5.99) 0.034

Weight of mother < 50 Kg 4.15 (1.50-11.46) 0.006

Previous hospitalizations 2.76 (1.38-5.56) 0.004

Education of father (below graduation) 3.18 (1.55-6.54) 0.002

Order of birth ( >3) 2.94 (1.21-7.13) 0.017

Religion (Hindu) 2.20 (1.25-3.88) 0.006

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 544 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

VAIDYANATHAN, et al. MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

• Malnutrition is common in children with congenital heart disease.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• Corrective intervention for congenital heart disease results in significant improvement in the nutritional status.

hitherto reported(3, 6-8,11-12,15) and is attributed to approach. The study underlines the importance of

the effects of increased total energy expenditure in identifying patients with reduced growth potential

these patients(4). Age at corrective intervention had and target them for a more aggressive nutritional

a significant impact on weight and weight/height surveillance after correction of CHD.

z-score (Table III). The risk of weight z-score ≤-2

was significantly higher in patients with age above 6 This study has certain limitations. We excluded

months at intervention compared to younger pa- patients undergoing palliative interventions (for

tients, suggesting the adverse impact of the persist- purpose of uniformity) and it is possible that these

ing hemodyanamic abnormality on growth. The patients have more complex forms of CHD and more

other determinants of malnutrition all point towards severe malnutrition. Also, a longer follow-up

a role for reduced growth potential. The adverse im- (presently ongoing) will provide more details

pact of low birthweight on nutritional recovery after regarding long-term somatic growth and factors

correction has been reported in other studies(7-9,16). associated with sub-optimal nutritional recovery.

We have used the CDC- 2000 reference values In conclusion, malnutrition is very common in

for estimation of z-scores as recommended by the children with CHD and is predicted by presence of

World Health Organization(19). Though separate congestive heart failure, older age at correction and

reference standards do exist for Indian Children(21), lower growth potential. Corrective intervention

previous studies from India have reported the significantly improves nutritional status on short-

reproducibility of the NCHS-CDC 2000 reference term follow-up.

standards in Indian setting(22). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results of this study could have significant The authors thank Mr Arun.C, physician assistant,

implications for physicians caring for children with for data collection and entry and Ms Mary Paul for

heart disease in developing countries. Presence of the data analysis.

CHF and age at correction were the only modifiable

determinants of malnutrition. The results of the study Contributors: BV designed, coordinated and supervised

underline the importance of referring patients with the study, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript

CHD and CHF for early corrective intervention and will act as the guarantor for the paper. SBN and UKB

(≤6 months) before significant malnutrition sets in. collected the data and were involved in analysis. SKR

analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript. SK and

We have previously reported the adverse impact of

SGR performed surgery. RKK supervised the study and

severe pre-operative malnutrition on somatic growth

critically reviewed the manuscript.

recovery in infants undergoing VSD closure(17).

Funding: Research grant from the Kerala State Council for

The dietary intake of calories did not impact Science, Technology and Environment.

nutritional status and hence the practice of Competing interests: None.

attempting aggressive calorie supplementation to

improve nutrition should be replaced by early REFERENCES

referral for corrective intervention. The significant 1. Mehrizi A, Drash A. Growth disturbance in

catch-up growth on short-term follow-up after congenital heart disease. J Pediatr 1962; 61: 418-

correction reinforces the importance of this 429.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 545 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

VAIDYANATHAN, et al. MALNUTRITION IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

2. Bayer LM, Robinson SJ. Growth history of children secundum atrial septal defect. Am J Cardiol 2000;

with congenital heart disease. Am J Dis Child 1969; 85:1472-1475.

117: 564-572.

13. Krishna Kumar R. Congenital heart disease in the

3. Varan B, Tokel K, Yilmaz G. Malnutrition and developing world. Congenital Cardiology Today

growth failure in cyanotic and acyanotic congenital (North American Edition) 2005;3(4):1-5.

heart disease with and without pulmonary

14. Kumar RK, Tynan MJ. Catheter interventions for

hypertension. Arch Dis Child 1999; 81: 49-52.

congenital heart disease in third world countries.

4. Ackerman IL, Karn CA, Denne SC, Ensing GJ, Pediatr Cardiol 2005; 26:1-9.

Leitch CA. Total but not resting energy expenditure

15. Vaidyanathan B, Roth SJ, Rao SG, Gauvreau K,

is increased in infants with ventricular septal

Shivaprakasha K, Kumar RK. Outcome of

defects. Pediatrics 1998; 102:1172-1177.

ventricular septal defect repair in a developing

5. Salzer HR, Haschke F, Wimmer M, Heil M, country. J Pediatr 2002; 140:736-741.

Schilling R. Growth and nutritional intake of infants

16. Bhatt M, Roth SJ, Kumar RK, Gauvreau K, Nair

with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 1989;

SG, Chengode S, et al. Management of infants with

10:17-23.

large, unrepaired ventricular septal defects and

6. Menon G, Poskitt EME. Why does congenital heart respiratory infection requiring mechanical

disease cause failure to thrive? Arch Dis Child ventilation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;

1985; 60:1134-1139. 127:1466-1473.

7. Weintraub RG, Menahem S. Early surgical closure 17. Vaidyanathan B, Roth SJ, Gauvreau K,

of a large ventricular septal defect: Influence on Shivaprakasha K , Rao SG, Kumar RK. Somatic

long term growth. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18: 552- growth after ventricular septal defect repair in

558. malnourished infants. J Pediatr 2006; 149: 205-

209.

8. Levy RJ, Rosenthal A, Miettinen OS, Nadas AS.

Determinants of growth in patients with ventricular 18. Mishra D, Singh H. Kuppuswamy socioeconomic

septal defect. Circulation 1978; 57:793-797. status scale - a Revision. Indian J Pediatr 2003; 70:

273-274.

9. Cheung MMH, Davis AM, Wilkinson JL,

Weintraub RG. Long term somatic growth after 19. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States.

repair of tetralogy of Fallot: evidence for From: URL: http/www.cdc.gov. Accessed July 1st

restoration of genetic growth potential. Heart 2003; 2006.

89:1340-1343.

20. de Onis M, Blossner M. World Health

10. Swan JW, Weintraub RG, Radley-Smith R, Yacoub Organization global database on child growth and

M. Long term growth following neonatal anatomic malnutrition. Program of Nutrition. Geneva: World

repair of transposition of the great arteries. Clin Health Organization; 1997.

Cardiol 1993; 16: 392-396.

21. Agarwal DK, Agarwal KN, Upadhyay SK, Mittal

11. Schuurmans FM, Pulles-Heintzberger CF, Gerver R, Prakash R, Rai S. Physical and sexual growth of

WJ. Long term growth of children with congenital affluent Indian children from 5 to 18 years. Indian

heart disease: A retrospective study. Acta Pediatr Pediatr 1992; 29:1203-1282.

1998; 87: 1250-1255.

22. Abel R, Sampathkumar V. Tamil Nadu nutritional

12. Rhee EK, Evangelista JK, Nigrin DJ, Erickson LC. survey comparing children aged 0-3 years with the

Impact of anatomic closure on somatic growth NCHS/CDC reference population. Indian J Pediatr

among small asymptomatic children with 1998; 65:565-572.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 546 VOLUME 45__JULY 17, 2008

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Working at Heights GuidelineDocumento15 pagineWorking at Heights Guidelinechanks498Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Immediate Effect of Ischemic Compression Technique and Transverse Friction Massage On Tenderness of Active and Latent Myofascial Trigger Points - A Pilot StudyDocumento7 pagineThe Immediate Effect of Ischemic Compression Technique and Transverse Friction Massage On Tenderness of Active and Latent Myofascial Trigger Points - A Pilot StudyJörgen Puis0% (1)

- CDM816DSpare Parts Manual (Pilot Control) 2Documento55 pagineCDM816DSpare Parts Manual (Pilot Control) 2Mohammadazmy Sobursyakur100% (1)

- Draft STATCOM Maintenance Schedule (FINAL)Documento36 pagineDraft STATCOM Maintenance Schedule (FINAL)Sukanta Parida100% (2)

- Syntorial NotesDocumento13 pagineSyntorial NotesdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Refrigeration Engineer Quick ReferenceDocumento2 pagineRefrigeration Engineer Quick ReferenceventilationNessuna valutazione finora

- Smart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before UseDocumento9 pagineSmart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before Useeliaszarmi100% (3)

- Epileptic Seizures Associated With Syncope Ictal Bradycardia andDocumento4 pagineEpileptic Seizures Associated With Syncope Ictal Bradycardia andirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Physical DevelopmentDocumento12 paginePhysical DevelopmentirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Determination Risk FactorDocumento7 pagineDetermination Risk FactorirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eye + ENT QuestionsDocumento57 pagineEye + ENT QuestionsirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- RSDK Thalassemia Integrated Center 2Documento24 pagineRSDK Thalassemia Integrated Center 2irenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Report GbsDocumento3 pagineCase Report GbsirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti-Tuberculosis Medication and The Liver Dangers and PDFDocumento5 pagineAnti-Tuberculosis Medication and The Liver Dangers and PDFirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Perspective of The Diagnosis and Management ofDocumento8 pagineA Perspective of The Diagnosis and Management ofirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ictal Bradycardia and Atrioventricular Block A CardiacDocumento3 pagineIctal Bradycardia and Atrioventricular Block A CardiacirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Significans Nutrition, TBDocumento10 pagineSignificans Nutrition, TBirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti-Tuberculosis Medication and The Liver Dangers andDocumento4 pagineAnti-Tuberculosis Medication and The Liver Dangers andirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- TB Milier PrintDocumento15 pagineTB Milier PrintgigibesiNessuna valutazione finora

- Significans Nutrition, TBDocumento8 pagineSignificans Nutrition, TBirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Review: Jacquie N Oliwa, Jamlick M Karumbi, Ben J Marais, Shabir A Madhi, Stephen M GrahamDocumento9 pagineReview: Jacquie N Oliwa, Jamlick M Karumbi, Ben J Marais, Shabir A Madhi, Stephen M GrahamirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- JurnalDocumento2 pagineJurnalziabazlinahNessuna valutazione finora

- Best 2Documento10 pagineBest 2irenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Significans Nutrition, TBDocumento10 pagineSignificans Nutrition, TBirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Cough in Children: Dwi Wastoro DadiyantoDocumento57 pagineChronic Cough in Children: Dwi Wastoro DadiyantoirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Immune Thrombocytopenia in Tuberculosis CausalDocumento5 pagineImmune Thrombocytopenia in Tuberculosis CausalirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eventratio DiafragmaDocumento9 pagineEventratio DiafragmairenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ketogenic Diet in Indian Children With Uncontroled EpilepsiDocumento5 pagineKetogenic Diet in Indian Children With Uncontroled EpilepsiirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- BronkiektasisDocumento7 pagineBronkiektasisirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Aspects of The Ketogenic DietDocumento12 pagineClinical Aspects of The Ketogenic DietirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- TB Milier PrintDocumento15 pagineTB Milier PrintgigibesiNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnostik Criteria Severe Acute Malnutrition Aged 0-6 BulanDocumento9 pagineDiagnostik Criteria Severe Acute Malnutrition Aged 0-6 BulanirenaNessuna valutazione finora

- DHT, VGOHT - Catloading Diagram - Oct2005Documento3 pagineDHT, VGOHT - Catloading Diagram - Oct2005Bikas SahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nano ScienceDocumento2 pagineNano ScienceNipun SabharwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Master of Business Administration in Aviation Management MbaamDocumento10 pagineMaster of Business Administration in Aviation Management MbaamAdebayo KehindeNessuna valutazione finora

- PalmistryDocumento116 paginePalmistrymarinoyogaNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Engineering Topics V4Documento409 pagineCivil Engineering Topics V4Ioannis MitsisNessuna valutazione finora

- Diels-Alder Reaction: MechanismDocumento5 pagineDiels-Alder Reaction: MechanismJavier RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 20Documento10 pagineLecture 20bilal5202050Nessuna valutazione finora

- Master Key Utbk Saintek 2022 (Paket 3) Bahasa InggrisDocumento5 pagineMaster Key Utbk Saintek 2022 (Paket 3) Bahasa InggrisRina SetiawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Mechanical Advantage HomeworkDocumento8 pagineMechanical Advantage Homeworkafeurbmvo100% (1)

- Digital Trail Camera: Instruction ManualDocumento20 pagineDigital Trail Camera: Instruction Manualdavid churaNessuna valutazione finora

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413Documento3 pagineBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413A V GamingNessuna valutazione finora

- ScheduleDocumento1 paginaScheduleparag7676Nessuna valutazione finora

- Afectiuni Si SimptomeDocumento22 pagineAfectiuni Si SimptomeIOANA_ROX_DRNessuna valutazione finora

- Relasi FuzzyDocumento10 pagineRelasi FuzzySiwo HonkaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Company Profile: Only Milling Since 1967Documento16 pagineCompany Profile: Only Milling Since 1967PavelNessuna valutazione finora

- CAT25256 EEPROM Serial 256-Kb SPI: DescriptionDocumento22 pagineCAT25256 EEPROM Serial 256-Kb SPI: DescriptionPolinho DonacimentoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chuyên Đề ConjunctionDocumento5 pagineChuyên Đề ConjunctionKhánh Linh TrịnhNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Principles of Remote SensingDocumento24 pagineBasic Principles of Remote Sensingfelipe4alfaro4salas100% (1)

- Monk - Way of The Elements RevisedDocumento3 pagineMonk - Way of The Elements Revisedluigipokeboy0% (1)

- Fluid Solids Operations: High HighDocumento20 pagineFluid Solids Operations: High HighPriscilaPrzNessuna valutazione finora

- Solid Mens ModuleDocumento158 pagineSolid Mens ModuleAzha Clarice VillanuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Output Process Input: Conceptual FrameworkDocumento4 pagineOutput Process Input: Conceptual FrameworkCHRISTINE DIZON SALVADORNessuna valutazione finora

- +chapter 6 Binomial CoefficientsDocumento34 pagine+chapter 6 Binomial CoefficientsArash RastiNessuna valutazione finora