Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ajrak Printing A Testimony To Ancient Indian Arts and Crafts Traditions Ijariie4351 PDF

Caricato da

Manasi PatilTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ajrak Printing A Testimony To Ancient Indian Arts and Crafts Traditions Ijariie4351 PDF

Caricato da

Manasi PatilCopyright:

Formati disponibili

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/316740527

AJRAK PRINTING: A TESTIMONY TO ANCIENT INDIAN ARTS AND CRAFTS

TRADITIONS

Article · May 2017

CITATIONS READS

0 895

4 authors, including:

Anshu Singh Choudhary

Amity university, Gwalior, India

19 PUBLICATIONS 6 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Adoption of green production technology in Indian Garment Industry View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Anshu Singh Choudhary on 08 May 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

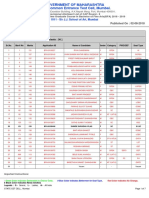

Vol-3 Issue-2 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396

AJRAK PRINTING: A TESTIMONY TO ANCIENT

INDIAN ARTS AND CRAFTS TRADITIONS

Ms Anshu Singh Choudhary, Asst Prof, Amity School of Fashion Design & Technology, Amity University

Madhya Pradesh

Abstract

Textile traditions in India date back to the Indus Valley civilization. Indian textiles were traded in the

Arab kingdoms, Egypt and East Africa. Textiles are deeply tangled with the identity of Gujarat and its people.

They reveal the innate aesthetics of artisans and their associations with the natural environment. Using a

combination of dying, weaving and printing, the craftsmen in Gujarat come up with the amazing materials.

Block printing is a very old textile craft of Gujarat. The craftsmen are specialized in using wooden blocks to

handprint complicated patterns on the yardage. One such block printing craft is Ajrakh. This printing skill came

to Gujarat from Sindh. Dhamadka village in Kutch is the chief centre for this fine art of resists printing and

mordant dyeing. It is one of the oldest types of block printing on textiles still practised in parts of Gujarat and

Rajasthan in India, and in Sindh in Pakistan. Textiles printed in this manner are hand -printed using natural dyes

on both sides by a lengthy and time-consuming process of resist printing.

Keywords: Printing, Ajrak, motif, dyeing, blocks

Introduction

The legacy of the Indus Valley Civilisation “Ajrakh” is a block-printing style. It is an ancient block-

printing method that originated in the Sindh and Kutch. The word 'ajrakh' itself denotes a number of different

concepts.

According to some sources, ajrakh is Arabic word which means blue, which is one of the chief colours

in this art form. Others say the word has been evolved from the two Hindi words- aaj rakh, meaning, keep it

today. According to few peoples, it means making beautiful. Although ajrakh printing is a part of the culture of

Sindh, its roots extend to the states of Rajasthan and Gujrat. The most important resource for washing fabric and

sustenance of raw materials like indigo dye and cotton was the Indus River.

In 16th Century khatris from the sindh migrated to kutch to thrive this art of printing in India. the

textile art was acknowledged by the king of kutch and thus the migration of khatris to kutch was encouraged.

Few khatris families migrated to Rajasthan & Gujrat and settled down there to excel the art of ajrak printing.

Now the supreme quality of ajrakh printed fabric is consistently produced by Khatris community as it became

their prime occupation in ajrakhpur village in kutch & barmer.

Celebration of nature

Ajrakh printing celebrates nature incredibly. This is evident in the aesthetics of the amalgamation of its

colours as well as motifs. In ajrak printing dark colours are used which symbolise nature. Indigo blue

symbolises twilight, crimson red symbolizes the earth. To outline motifs and defines symmetrical designs black

and white is used. The use of traditional natural dyes is being resumed gradually even though eco friendly

synthetic dyes were prevalent. Indigo dye is obtained from the indigo plant. Craftsmen used to grow indigo

plants profusely along the Indus River. Red is obtained from alizarin found in the roots of madder plants. From

iron shavings, millet flour and molasses black is obtained with the addition of ground tamarind seeds to thicken

the dye. The contemporary ajrakh prints have intensely vibrant contrasting colours like yellow, orange & rust

4351 www.ijariie.com 5893

Vol-3 Issue-2 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396

The use of traditional elaborate motifs is still popular in ajrakh printing, which is the legacy of earlier

generations. Symmetrical geometric jewel like shape symbolises natural elements like flower, leaves & stars.

Trefoil is the most important motif found in ajrak printing which is thought to be made of three sundiscs joined

together to represent the cohesive unity of the gods of earth, water & sun. All motifs are engraved around a

central point and are repeated across the fabric in a grid forming something similar to web-like design, or the

central jaal. This jaal is made of vertical, diagonal and horizontal lines. In addition, border designs are also

printed aligned both horizontally as well as vertically and frame the central portion, distinguishing one ajrakh

from another. To differeciate the the layouts of borders a double margin is used to print the lateral ends of the

fabric.

Mens of Jat & Meghwal community wear ajrakh printed fabric as safa (Shoulder fabric) and lungi.

Low income groups are spotted with Ekpuri ajrakh (Printed on one side only). High income group wear bipuri

ajrak (printed on both sides) as shoulder-wear during ceremonies like wedding to mark the status symbol. On

some special occasions, it is presented to bridegrooms. Everyday usage, like bed spreads, dupattas, scarves,

hammocks, and even gifts are printed with ajrakh art.

Processing Ajrakh

Ajrakh printing is arduous & long process that requires different of stages of printing and washing the

fabric repeatedly with different mordant’s & natural dye. It follows the resist style of printing which prohibits

absorption on the areas meant not to be coloured and permits absorption of a dye in the required areas and. The

stages are elaborated below:

Saaj: Starch is removed from the fabric by washing & then dipping in a solution of camel dung, castor oil &

soda ash. Then it is wrung out & kept overnight. In the morning the fabric is allowed to partially dry under the

sun & then again dipped in the solution. The complete process is repeated about eight times until foam is

produced by rubbing the fabric. Then finally washed with plain water.

Kasano: In this process fabric is washed in a solution obtained from the nuts of harde tree called as myrobalan.

It is first mordant to be used in dyeing process. After that the fabric is dried in sun from both sides & extra

myrobalan is brushed off from the fabric.

Khariyanu: A resist of gum Arabic (babool tree resin) & lime is printed on both sides of fabric using carved

wooden blocks to outline the motif in white colour. This white outline printing is called as rekh.

Kat: For about 2 0 days the the mixture of Jaggery & iron scrap with water are kept, to make water ferrous.

After that tamarind seed pwder is added to ferrous water & boiled to make a thick paste called as kat. And kat is

printed on both sides of fabric.

Gach: Gum Arabic, alum & Clay are mixed to form a paste which is to be used as a resist in printing. At the

same time gum Arabic & lime is also printed. The combined phase is called as gach. Finely ground cow dung

or saw dust is spread on the printed portion to shield the clay

Clay, alum and gum Arabic are mixed to form a paste which is to be used for the next resist printing. A

resist of gum Arabic and lime is also printed at the same time. This combined phase is known as gach. To shield

the clay from smudging, saw dust or finely ground cow dung is spread on the printed portion. After this stage,

the cloth is dried naturally for about 7-10 days.

Indigo dyeing: The fabric is dyed in indigo. Next, it is kept in the sun to dry and then is dyed again in indigo

twice to coat it uniformly.

Vichcharnu: The fabric is washed thoroughly to remove all the resist print and extra dye.

4351 www.ijariie.com 5894

Vol-3 Issue-2 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396

Rang: Next the fabric is put to boil with alizarin, i.e. synthetic madder in order to impart a bright shining red

colour to alum residue portion. Alum works as a mordant to fix the red colour. The grey areas from the black

printing steps turn into a deeper hue. For other colours, the fabric is boiled with a different dye. Madder root

imparts an orange colour, henna adds a light yellowish green colour, and rhubarb root gives a faint brownish

colour.

In ajrakh printing, the fabric is first printed with a resist paste and then it is dyed. This process is

repeated several times with different kinds of dyes with the aim of achieving the final design in the deep blue

and red shade. This process consumes a lot of time. The longer the time span before commencing the next stage,

the more rich and vibrant the final print becomes. Hence, this process can consume up to two weeks, and

consequently results in the formation of exquisitely beautiful and captivating designs of the ajrakh.

The role of the industries

Water plays a significant role in ajrakh printing. Craftsmen treat the fabric with mordants, dyes, oils,

etc. Water impacts everything from the shades and hues of the colours themselves to the success or failure of the

complete process. The iron content in water is the decisive factor which determines the quality of the final

product.

Dhamadka was the chief location of ajrakh printing for a considerable span of time due to the favourable source

of water. But after the 2001 earthquake, the iron content in water increased heavily and the water turned to be

unusable. Thus, the artisans from Dhamadka village shifted to a new base and named it Ajrakhpur. They have

taken initiative in harvesting water keeping in view the fragile eco-system.

Ajrakh printing in Sindh, Kutch and Barmer, are almost similar in terms of production technique,

motifs and use of colours. This is due to the fact that craftsmen in these areas descend from the same caste-

families of the Khatri community who migrated to Kutch and Barmer from Sindh in the 16th century, and who

are the descendents of the Indus Valley Civilisation. At present, the Khatri families are distinguished for

carrying on with the traditional technique of ajrakh printing.

The Khatri community had been involved in ajrakh printing in the village of Dhamadka long before the

destructive earthquake of 2001. All Ajrakh printers were shifted to the new village of Ajrakhpur, which was set

up primarily to commemorate the art of Ajrakh printing and its highly proficient artisans. It is chiefly the Khatris

who have acquired perfection in this craft, and are carrying on the legacy of traditional technique of their

ancestors.

A plethora of problems

Ajrakh craftsperson's today face a number of problems, which hinder work.

Use of synthetic dyes and sophisticated machinery: Use of eco-friendly and synthetic dyes and sophisticated

machinery which has lessened production time to a great extent is proving to be a threat to the age-old traditions

of this textile art.

Government loans: It is cumbersome for artisans to get government loans which in turn discourage them from

setting up their own printing units.

High cost of blocks: The high cost of wooden blocks used in Ajrakh printing imposes a great financial burden

on artisans as one block costs as much as Rs 3,000.

Crunch of water resources: There is lack of water resources which is a mandatory criterion for ajrakh printing

in and around printing hubs.

4351 www.ijariie.com 5895

Vol-3 Issue-2 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396

Lack of new crafts persons: Due to the lack of payback and great labour requirement, the upcoming generation

is hesitant in adopting this craft as chief occupation.

Traditionally, vegetable dyes were used by ajrakh printers, but soon they began to use naphthol dyes

and synthetic dyes realising that vegetable dyes were proving to be too expensive. But with the revival of the

craft once again, ajrakh printers have reverted to the use of natural dyes. New motifs are being added to the

design library day by day. Earlier, the body and the border used to be same, but now complementary borders are

in vogue.

Earlier, blocks used to be made in a place called Pethapur. Now, blocks are made in the homes with the

help of machine-like drills. And, instead of natural water resources, modern printers use water from borewells.

The craftspeople are also planning to establish a treatment plant for treating polluted water. Changing times

have called for critical changes both in terms of utility and design. But the beauty of the traditional art has

withstood the test of time. A number of hubs of ajrakh printing have cropped up across India as well as Pakistan

proving that art is supreme and it transcends national boundaries.

In tune with changing times

A number of NGOs are currently engaged in making efforts to uplift this craft by providing new inputs

to the craftspeople. The NGOs conduct year-long training programmes to train aspiring craftsperson in all

relevant aspects of the art and give them monetary support during the same. NGOs also back them in selling

their products in the market and earn due profits. But the number of such NGOs is not sufficient in proportion to

the number of craftspeople needing this assistance. Thus, the government, the NGOs and those who are devoted

to this craft should come forward and devise ways and means to shield the interest of craftsmen who have been

nurturing this art for ages.

In spite of environmental calamities, industrialisation and changing political regimes, the traditional

craft of ajrakh has survived. Craftspersons are revitalising the age-old use of natural dyes for western markets.

The handmade, ecofriendly and natural dyes are preferred to non-eco-friendly machine-made and artificial dyes

and colours.

With passage of time, ajrakh printers are now open to trying out new motifs, designs, dyes, materials

and want to keep pace with the growing and changing contemporary world of fashion. At present, the printing

art is being impacted by market demand and the new crop of ajrakh printers are prepared to accept and

experiment with new pattern inputs provided by fashion designers. Hence, it has received a new lease of

recognition both nationally as well as internationally. There is hope that these are not just transient fashion

trends and that the ajrakh artisans will carry on the tradition of catering to the world with a fascination for highly

proficient, elaborate, handcrafted textiles for generations to come.

Refrences

1. Adrin Duarte, The crafts and Textiles of Sindh and Baluchistan. (Institute of Sindhology,1982)

2. John Irwin and Margaret Hall, Indian, Painted and Printed Fabrics Vol I(Ahmedadabad, calico

Muesuem, 1971)

3. Pupul Jayakar and John Irwin, Textiles and Ornaments of India. (The museum of Modern Art, New

York,1956)

4. Bilgrami, Noorjehan. Ajrak Cloth from the Soil of Sindh: 2002

5. Anjali Karolia and Heli Buch,Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, Ajrakh the resist printed fabric

of Gujarat ,2008

6. http://pachome1.pacific.net.sg/~makhdoom/ajrak.html

7. http://www.handprintingguiderajasthan.in/its-heritage-art-printing-in-jaipur-saanganer-and-

bagru/evolution-of-specialized-crafts-like-ajrakh-gold-leaf-printing-and-saudagiri/

8. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajrak

4351 www.ijariie.com 5896

View publication stats

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Chinese TextilesDocumento7 pagineChinese TextilesManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Indian Sarees and Brocade FabricsDocumento43 pagineTypes of Indian Sarees and Brocade FabricsManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Traditional Pipli Applique Craft DocumentaryDocumento22 pagineTraditional Pipli Applique Craft DocumentaryManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Chinese TextilesDocumento7 pagineChinese TextilesManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- JJ Seats 2018Documento7 pagineJJ Seats 2018Manasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- BC1 PDFDocumento7 pagineBC1 PDFManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Fabric DictionaryDocumento74 pagineFabric DictionaryManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Fabric DictionaryDocumento74 pagineFabric DictionaryManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- State CET Cell Mumbai vacancy details for BFA coursesDocumento4 pagineState CET Cell Mumbai vacancy details for BFA coursesManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Sel List MSDocumento32 pagineSel List MSManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- 1011 - Sir J.J. School of Art, MumbaiDocumento7 pagine1011 - Sir J.J. School of Art, MumbaiManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Printed TextilesDocumento10 paginePrinted TextilesManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- L 7 P T I: Esson Ainted Extiles of NdiaDocumento9 pagineL 7 P T I: Esson Ainted Extiles of NdiaManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- An Insight Into The Ikat Technology in India: Ancient To Modern EraDocumento25 pagineAn Insight Into The Ikat Technology in India: Ancient To Modern EraManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Bagh Block PrintingDocumento13 pagineBagh Block PrintingManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Bagh Block PrintingDocumento13 pagineBagh Block PrintingManasi PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Traditional Indian Costumes and TextilesDocumento11 pagineTraditional Indian Costumes and TextilesMariaMaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- SHS Track and Strand - FinalDocumento36 pagineSHS Track and Strand - FinalYuki BombitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iron FoundationsDocumento70 pagineIron FoundationsSamuel Laura HuancaNessuna valutazione finora

- Frendx: Mara IDocumento56 pagineFrendx: Mara IKasi XswlNessuna valutazione finora

- 0807 Ifric 16Documento3 pagine0807 Ifric 16SohelNessuna valutazione finora

- ILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsDocumento17 pagineILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsNelyn LosteNessuna valutazione finora

- Bias in TurnoutDocumento2 pagineBias in TurnoutDardo CurtiNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisDocumento15 pagineManaging a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisGareth McKnight100% (2)

- UAE Cooling Tower Blow DownDocumento3 pagineUAE Cooling Tower Blow DownRamkiNessuna valutazione finora

- First Time Login Guidelines in CRMDocumento23 pagineFirst Time Login Guidelines in CRMSumeet KotakNessuna valutazione finora

- 486 Finance 17887 Final DraftDocumento8 pagine486 Finance 17887 Final DraftMary MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Application Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFDocumento7 pagineApplication Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFIrshad KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Statement of Purpose EitDocumento3 pagineStatement of Purpose EitSajith KvNessuna valutazione finora

- Future42 1675898461Documento48 pagineFuture42 1675898461Rodrigo Garcia G.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Electric Vehicles PresentationDocumento10 pagineElectric Vehicles PresentationKhagesh JoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Zeng 2020Documento11 pagineZeng 2020Inácio RibeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Sterilization and DisinfectionDocumento100 pagineSterilization and DisinfectionReenaChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 - 30 July 1894) Was An English EssayistDocumento4 pagineWalter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 - 30 July 1894) Was An English EssayistwiweksharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 1 English For KidsDocumento4 pagineGrade 1 English For Kidsvivian 119190156Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 4-LS1 Eng. LAS (Types of Verbals)Documento14 pagineWeek 4-LS1 Eng. LAS (Types of Verbals)DONALYN VERGARA100% (1)

- Friday August 6, 2010 LeaderDocumento40 pagineFriday August 6, 2010 LeaderSurrey/North Delta LeaderNessuna valutazione finora

- MAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONDocumento9 pagineMAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONEinstein Salcedo100% (1)

- Lesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewDocumento6 pagineLesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewVincent Joshua TriboNessuna valutazione finora

- MEE2041 Vehicle Body EngineeringDocumento2 pagineMEE2041 Vehicle Body Engineeringdude_udit321771Nessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Research 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 1 - Nature and Inquiry of Research - Version 3Documento53 paginePractical Research 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 1 - Nature and Inquiry of Research - Version 3Iris Rivera-PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Prep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Documento1 paginaPrep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Phương LanNessuna valutazione finora

- Round Rock Independent School District: Human ResourcesDocumento6 pagineRound Rock Independent School District: Human Resourcessho76er100% (1)

- Julian's GodsDocumento162 pagineJulian's Godsअरविन्द पथिक100% (6)

- Volvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical DataDocumento2 pagineVolvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical Dataaquilescachoyo50% (2)

- Common Application FormDocumento5 pagineCommon Application FormKiranchand SamantarayNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Documento154 pagineBhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Ven. Tathālokā TherīNessuna valutazione finora