Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Free Exercise of Religion - Kimmy

Caricato da

Kimmy DomingoTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Free Exercise of Religion - Kimmy

Caricato da

Kimmy DomingoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

U.S.

Supreme Court deprivation of liberty without due process of law in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. P. 310 U. S. 304.

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940)

So held as it was applied to persons engaged in distributing

Cantwell v. Connecticut literature purporting to be religious, and soliciting contributions to

be used for the publication of such literature.

No. 632

A State constitutionally may, by general and nondiscriminatory

Argued March 29, 1940 legislation, regulate the time, place and manner of soliciting upon

its streets, and of holding meetings thereon, and may in other

respects safeguard the peace, good order and comfort of the

Decided May 20, 1940 community.

310 U.S. 296 Page 310 U. S. 297

APPEAL FROM AND CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT The statute here, however, is not such a regulation. If a certificate

is issued, solicitation is permitted without other restriction; but if a

OF ERRORS OF CONNECTICUT certificate is denied, solicitation is altogether prohibited.

Syllabus 5. The fact that arbitrary or capricious action by the licensing

officer is subject to judicial review cannot validate the statute. A

1. The fundamental concept of liberty embodied in the Fourteenth previous restraint by judicial decision after trial is as obnoxious

Amendment embraces the liberties guaranteed by the First under the Constitution as restraint by administrative action. P. 310

Amendment. P. 310 U. S. 303. U. S. 306.

2. The enactment by a State of any law respecting an 6. The common law offense of breach of the peace may be

establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof is committed not only by acts of violence, but also by acts and words

forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment. P. 310 U. S. 303. likely to produce violence in others. P. 310 U. S. 308.

3. Under the constitutional guaranty, freedom of conscience and of 7. Defendant, while on a public street endeavoring to interest

religious belief is absolute; although freedom to act in the exercise passerby in the purchase of publications, or in making

of religion is subject to regulation for the protection of society. Such contributions, in the interest of what he believed to be true religion,

regulation, however, in attaining a permissible end, must not induced individuals to listen to the playing of a phonograph record

unduly infringe the protected freedom. Pp.310 U. S. 303-304. describing the publications. The record contained a verbal attack

upon the religious denomination of which the listeners were

4. A state statute which forbids any person to solicit money or members, provoking their indignation and a desire on their part to

valuables for any alleged religious cause, unless a certificate strike the defendant, who thereupon picked up his books and

therefor shall first have been procured from a designated official, phonograph and went on his way. There was no showing that

who is required to determine whether such cause is a religious one defendant's deportment was noisy, truculent, overbearing, or

and who may withhold his approval if he determines that it is not, is offensive; nor was it claimed that he intended to insult or affront

a previous restraint upon the free exercise of religion, and a the listeners by playing the record; nor was it shown that the sound

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 1 of 267

of the phonograph disturbed persons living nearby, drew a crowd, Page 310 U. S. 301

or impeded traffic.

they made the point that they could not be found guilty on the fifth

Held, that defendant's conviction of the common law offense of count without violation of the Amendment.

breach of the peace was violative of constitutional guarantees of

religious liberty and freedom of speech. Pp. 310 U. S. 307 et seq. We have jurisdiction on appeal from the judgments on the third

count, as there was drawn in question the validity of a state statute

126 Conn. 1; 8 A.2d 533, reversed. under the Federal Constitution and the decision was in favor of

validity. Since the conviction on the fifth count was not based upon

APPEAL from, and certiorari (309 U.S. 626) to review, a judgment a statute, but presents a substantial question under the Federal

which sustained the conviction of all the defendants on one count Constitution, we granted the writ of certiorari in respect of it.

of an information and the conviction of one of the defendants on

another count. The convictions were challenged as denying the The facts adduced to sustain the convictions on the third count

constitutional rights of the defendants. follow. On the day of their arrest, the appellants were engaged in

going singly from house to house on Cassius Street in New Haven.

Page 310 U. S. 300 They were individually equipped with a bag containing books and

pamphlets on religious subjects, a portable phonograph, and a set

MR. JUSTICE ROBERTS delivered the opinion of the Court. of records, each of which, when played, introduced, and was a

description of, one of the books. Each appellant asked the person

who responded to his call for permission to play one of the records.

Newton Cantwell and his two sons, Jesse and Russell, members of a If permission was granted, he asked the person to buy the book

group known as Jehovah's Witnesses and claiming to be ordained described, and, upon refusal, he solicited such contribution towards

ministers, were arrested in New Haven, Connecticut, and each was the publication of the pamphlets as the listener was willing to

charged by information in five counts, with statutory and common make. If a contribution was received, a pamphlet was delivered

law offenses. After trial in the Court of Common Pleas of New Haven upon condition that it would be read.

County, each of them was convicted on the third count, which

charged a violation of § 294 of the General Statutes of Connecticut,

[Footnote 1] and on the fifth count, which charged commission of Cassius Street is in a thickly populated neighborhood where about

the common law offense of inciting a breach of the peace. On ninety percent of the residents are Roman Catholics. A phonograph

appeal to the Supreme Court, the conviction of all three on the third record, describing a book entitled "Enemies," included an attack on

count was affirmed. The conviction of Jesse Cantwell on the fifth the Catholic religion. None of the persons interviewed were

count was also affirmed, but the conviction of Newton and Russell members of Jehovah's Witnesses.

on that count was reversed, and a new trial ordered as to them.

[Footnote 2] The statute under which the appellants were charged provides:

By demurrers to the information, by requests for rulings of law at "No person shall solicit money, services, subscriptions or any

the trial, and by their assignments of error in the State Supreme valuable thing for any alleged religious, charitable

Court, the appellants pressed the contention that the statute under

which the third count was drawn was offensive to the due process Page 310 U. S. 302

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because, on its face and as

construed and applied, it denied them freedom of speech and or philanthropic cause, from other than a member of the

prohibited their free exercise of religion. In like manner, organization for whose benefit such person is soliciting or within

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 2 of 267

the county in which such person or organization is located unless were tempted to strike Cantwell unless he went away. On being told

such cause shall have been approved by the secretary of the public to be on his way, he left their presence. There was no evidence that

welfare council. Upon application of any person in behalf of such he was personally offensive or entered into any argument with

cause, the secretary shall determine whether such cause is a those he interviewed.

religious one or is a bona fide object of charity or philanthropy and

conforms to reasonable standards of efficiency and integrity, and, if The court held that the charge was not assault or breach of the

he shall so find, shall approve the same and issue to the authority peace or threats on Cantwell's part, but invoking or inciting others

in charge a certificate to that effect. Such certificate may be to breach of the peace, and that the facts supported the conviction

revoked at any time. Any person violating any provision of this of that offense.

section shall be fined not more than one hundred dollars or

imprisoned not more than thirty days or both." First. We hold that the statute, a construed and applied to the

appellants, deprives them of their liberty without due process of

The appellants claimed that their activities were not within the law in contravention of the Fourteenth Amendment. The

statute, but consisted only of distribution of books, pamphlets, and fundamental concept of liberty embodied in that Amendment

periodicals. The State Supreme Court construed the finding of the embraces the liberties guaranteed by the First Amendment.

trial court to be that, [Footnote 3] The First Amendment declares that Congress shall

make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting

"in addition to the sale of the books and the distribution of the the free exercise thereof. The Fourteenth Amendment has rendered

pamphlets, the defendants were also soliciting contributions or the legislatures of the states as incompetent as Congress to enact

donations of money for an alleged religious cause, and thereby such laws. The constitutional inhibition of legislation on the subject

came within the purview of the statute." of religion has a double aspect. On the one hand, it forestalls

compulsion by law of the acceptance of any creed or the practice of

It overruled the contention that the Act, as applied to the any form of worship. Freedom of conscience and freedom to adhere

appellants, offends the due process clause of the Fourteenth to such religious organization or form of worship as the individual

Amendment because it abridges or denies religious freedom and may choose cannot be restricted by law. On the other hand, it

liberty of speech and press. The court stated that it was the safeguards the free exercise of the chosen form of religion. Thus,

solicitation that brought the appellants within the sweep of the Act, the Amendment embraces two concepts -- freedom to believe and

and not their other activities in the dissemination of literature. It freedom to act. The first is absolute, but, in the nature of things,

declared the legislation constitutional as an effort by the State to the

protect the public against fraud and imposition in the solicitation of

funds for what purported to be religious, charitable, or philanthropic Page 310 U. S. 304

causes.

second cannot be. Conduct remains subject to regulation for the

The facts which were held to support the conviction of Jesse protection of society. [Footnote 4] The freedom to act must have

Cantwell on the fifth count were that he stopped appropriate definition to preserve the enforcement of that

protection. In every case, the power to regulate must be so

Page 310 U. S. 303 exercised as not, in attaining a permissible end, unduly to infringe

the protected freedom. No one would contest the proposition that a

two men in the street, asked, and received, permission to play a State may not, by statute, wholly deny the right to preach or to

phonograph record, and played the record "Enemies," which disseminate religious views. Plainly, such a previous and absolute

attacked the religion and church of the two men, who were restraint would violate the terms of the guarantee. [Footnote 5] It is

Catholics. Both were incensed by the contents of the record, and equally clear that a State may, by general and nondiscriminatory

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 3 of 267

legislation, regulate the times, the places, and the manner of determining its right to survive is a denial of liberty protected by

soliciting upon its streets, and of holding meetings thereon, and the First Amendment and included in the liberty which is within the

may in other respects safeguard the peace, good order, and protection of the Fourteenth.

comfort of the community without unconstitutionally invading the

liberties protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The appellants The State asserts that, if the licensing officer acts arbitrarily,

are right in their insistence that the Act in question is not such a capriciously, or corruptly, his action is subject to judicial correction.

regulation. If a certificate is procured, solicitation is permitted Counsel refer to the rule prevailing in Connecticut that the decision

without restraint, but, in the absence of a certificate, solicitation is of a commission or an administrative official will be reviewed upon

altogether prohibited. a claim that

The appellants urge that to require them to obtain a certificate as a "it works material damage to individual or corporate rights, or

condition of soliciting support for their views amounts to a prior invades or threatens such rights, or is so unreasonable as to justify

restraint on the exercise of their religion within the meaning of the judicial intervention, or is not consonant with justice, or that a legal

Constitution. The State insists that the Act, as construed by the duty has not

Supreme Court of Connecticut, imposes no previous restraint upon

the dissemination of religious views or teaching, but merely Page 310 U. S. 306

safeguards against the perpetration of frauds under the cloak of

religion. Conceding that this is so, the question remains whether

the method adopted by Connecticut to been performed. [Footnote 6]"

Page 310 U. S. 305 It is suggested that the statute is to be read as requiring the officer

to issue a certificate unless the cause in question is clearly not a

religious one, and that, if he violates his duty, his action will be

that end transgresses the liberty safeguarded by the Constitution. corrected by a court.

The general regulation, in the public interest, of solicitation, which To this suggestion there are several sufficient answers. The line

does not involve any religious test and does not unreasonably between a discretionary and a ministerial act is not always easy to

obstruct or delay the collection of funds is not open to any mark, and the statute has not been construed by the state court to

constitutional objection, even though the collection be for a impose a mere ministerial duty on the secretary of the welfare

religious purpose. Such regulation would not constitute a prohibited council. Upon his decision as to the nature of the cause the right to

previous restraint on the free exercise of religion or interpose an solicit depends. Moreover, the availability of a judicial remedy for

inadmissible obstacle to its exercise. abuses in the system of licensing still leaves that system one of

previous restraint which, in the field of free speech and press, we

It will be noted, however, that the Act requires an application to the have held inadmissible. A statute authorizing previous restraint

secretary of the public welfare council of the State; that he is upon the exercise of the guaranteed freedom by judicial decision

empowered to determine whether the cause is a religious one, and after trial is as obnoxious to the Constitution as one providing for

that the issue of a certificate depends upon his affirmative action. If like restraint by administrative action. [Footnote 7]

he finds that the cause is not that of religion, to solicit for it

becomes a crime. He is not to issue a certificate as a matter of Nothing we have said is intended even remotely to imply that,

course. His decision to issue or refuse it involves appraisal of facts, under the cloak of religion, persons may, with impunity, commit

the exercise of judgment, and the formation of an opinion. He is frauds upon the public. Certainly penal laws are available to punish

authorized to withhold his approval if he determines that the cause such conduct. Even the exercise of religion may be at some slight

is not a religious one. Such a censorship of religion as the means of

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 4 of 267

inconvenience in order that the State may protect its citizens from Page 310 U. S. 308

injury. Without doubt, a State may protect its citizens from

fraudulent solicitation by requiring a stranger in the community, would weigh heavily in any challenge of the law as infringing

before permitting him publicly to solicit funds for any purpose, to constitutional limitations. Here, however, the judgment is based on

establish his identity and his authority to act for the cause which he a common law concept of the most general and undefined nature.

purports to represent. [Footnote 8] The State is likewise free to The court below has held that the petitioner's conduct constituted

regulate the time the commission of an offense under the state law, and we accept

its decision as binding upon us to that extent.

Page 310 U. S. 307

The offense known as breach of the peace embraces a great variety

and manner of solicitation generally, in the interest of public safety, of conduct destroying or menacing public order and tranquility. It

peace, comfort or convenience. But to condition the solicitation of includes not only violent acts, but acts and words likely to produce

aid for the perpetuation of religious views or systems upon a violence in others. No one would have the hardihood to suggest

license, the grant of which rests in the exercise of a determination that the principle of freedom of speech sanctions incitement to riot,

by state authority as to what is a religious cause, is to lay a or that religious liberty connotes the privilege to exhort others to

forbidden burden upon the exercise of liberty protected by the physical attack upon those belonging to another sect. When clear

Constitution. and present danger of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon

the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety,

Second. We hold that, in the circumstances disclosed, the peace, or order appears, the power of the State to prevent or

conviction of Jesse Cantwell on the fifth count must be set aside. punish is obvious. Equally obvious is it that a State may not unduly

Decision as to the lawfulness of the conviction demands the suppress free communication of views, religious or other, under the

weighing of two conflicting interests. The fundamental law declares guise of conserving desirable conditions. Here we have a situation

the interest of the United States that the free exercise of religion be analogous to a conviction under a statute sweeping in a great

not prohibited and that freedom to communicate information and variety of conduct under a general and indefinite characterization,

opinion be not abridged. The State of Connecticut has an obvious and leaving to the executive and judicial branches too wide a

interest in the preservation and protection of peace and good order discretion in its application.

within her borders. We must determine whether the alleged

protection of the State's interest, means to which end would, in the Having these considerations in mind, we note that Jesse Cantwell,

absence of limitation by the Federal Constitution, lie wholly within on April 26, 1938, was upon a public street, where he had a right to

the State's discretion, has been pressed, in this instance, to a point be and where he had a right peacefully to impart his views to

where it has come into fatal collision with the overriding interest others. There is no showing that his deportment was noisy,

protected by the federal compact. truculent, overbearing or offensive. He requested of two

pedestrians permission to play to them a phonograph record. The

Conviction on the fifth count was not pursuant to a statute evincing permission was granted. It is not claimed that he

a legislative judgment that street discussion of religious affairs,

because of its tendency to provoke disorder, should be regulated, Page 310 U. S. 309

or a judgment that the playing of a phonograph on the streets

should in the interest of comfort or privacy be limited or prevented. intended to insult or affront the hearers by playing the record. It is

Violation of an Act exhibiting such a legislative judgment and plain that he wished only to interest them in his propaganda. The

narrowly drawn to prevent the supposed evil would pose a question sound of the phonograph is not shown to have disturbed residents

differing from that we must here answer. [Footnote 9] Such a of the street, to have drawn a crowd, or to have impeded traffic.

declaration of the State's policy

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 5 of 267

Thus far, he had invaded no right or interest of the public, or of the Cantwell, however misguided others may think him, conceived to

men accosted. be true religion.

The record played by Cantwell embodies a general attack on all In the realm of religious faith, and in that of political belief, sharp

organized religious systems as instruments of Satan and injurious differences arise. In both fields the tenets of one man may seem

to man; it then singles out the Roman Catholic Church for strictures the rankest error to his neighbor. To persuade others to his own

couched in terms which naturally would offend not only persons of point of view, the pleader, as we know, at times resorts to

that persuasion, but all others who respect the honestly held exaggeration, to vilification of men who have been, or are,

religious faith of their fellows. The hearers were, in fact, highly prominent in church or state, and even to false statement. But the

offended. One of them said he felt like hitting Cantwell, and the people of this nation have ordained, in the light of history, that, in

other that he was tempted to throw Cantwell off the street. The one spite of the probability of excesses and abuses, these liberties are,

who testified he felt like hitting Cantwell said, in answer to the in the long view, essential to enlightened opinion and right conduct

question "Did you do anything else or have any other reaction?" on the part of the citizens of a democracy.

"No, sir, because he said he would take the victrola, and he went."

The other witness testified that he told Cantwell he had better get The essential characteristic of these liberties is that, under their

off the street before something happened to him, and that was the shield, many types of life, character, opinion and belief can develop

end of the matter, as Cantwell picked up his books and walked up unmolested and unobstructed. Nowhere is this shield more

the street. necessary than in our own country, for a people composed of many

races and of many creeds. There are limits to the exercise of these

Cantwell's conduct, in the view of the court below, considered apart liberties. The danger in these times from the coercive activities of

from the effect of his communication upon his hearers, did not those who in the delusion of racial or religious conceit would incite

amount to a breach of the peace. One may, however, be guilty of violence and breaches of the peace in order to deprive others of

the offense if he commit acts or make statements likely to provoke their equal right to the exercise of their liberties, is emphasized by

violence and disturbance of good order, even though no such events familiar to all. These and other transgressions of those limits

eventuality be intended. Decisions to this effect are many, but the States appropriately may punish.

examination discloses that, in practically all, the provocative

language which was held to amount to a breach of the peace Page 310 U. S. 311

consisted of profane, indecent, or abusive remarks directed to the

person of the hearer. Resort to epithets or Although the contents of the record not unnaturally aroused

animosity, we think that, in the absence of a statute narrowly

Page 310 U. S. 310 drawn to define and punish specific conduct as constituting a clear

and present danger to a substantial interest of the State, the

personal abuse is not in any proper sense communication of petitioner's communication, considered in the light of the

information or opinion safeguarded by the Constitution, and its constitutional guarantees, raised no such clear and present menace

punishment as a criminal act would raise no question under that to public peace and order as to render him liable to conviction of

instrument. the common law offense in question. [Footnote 10]

We find in the instant case no assault or threatening of bodily harm, The judgment affirming the convictions on the third and fifth counts

no truculent bearing, no intentional discourtesy, no personal abuse. is reversed, and the cause is remanded for further proceedings not

On the contrary, we find only an effort to persuade a willing listener inconsistent with this opinion.

to buy a book or to contribute money in the interest of what

Reversed.

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 6 of 267

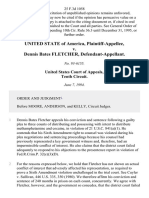

not barred by the rule of Johnson v. United States, 318 U. S. 189,

from reasserting here that no part of the indictment should have

U.S. Supreme Court been submitted to the jury. P. 322 U. S. 85.

United States v. Ballard, 322 U.S. 78 (1944) 3. The District Court properly withheld from the jury all questions

concerning the truth or falsity of respondents' religious beliefs or

doctrines. This course was required by the First Amendment's

United States v. Ballard

guarantee of religious freedom. P. 322 U. S. 86.

No. 472

The preferred position given freedom of religion by the First

Amendment is not limited to any particular religious group or to any

Argued March 3, 6, 1944 particular type of religion but applies to all. P. 322 U. S. 87.

Decided April 24, 1944 4. Respondents may urge in support of the judgment of the Circuit

Court of Appeals points which that court reserved, but, since these

322 U.S. 78 were not fully presented here either in the briefs or oral argument,

they may more appropriately be considered by that court upon

CERTIORARI TO THE CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS remand. P. 322 U. S. 88.

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT 138 F.2d 540 reversed.

Syllabus Certiorari, 320 U.S. 733, to review the reversal of convictions for

using the mails to defraud and conspiracy.

Upon an indictment charging use of the mails to defraud, and

conspiracy so to do, respondents were convicted in the District Page 322 U. S. 79

Court. The indictment charged a scheme to defraud through

representations -- involving respondents' religious doctrines or MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS delivered the opinion of the Court.

beliefs -- which were alleged to be false and known by the

respondents to be false. Holding that the District Court had Respondents were indicted and convicted for using, and conspiring

restricted the jury to the issue of respondents' good faith and that to use, the mails to defraud. § 215 Criminal Code, 18 U.S.C. § 338; §

this was error, the Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and granted a 37 Criminal Code, 18 U.S.C. § 88. The indictment was in twelve

new trial. counts. It charged a scheme to defraud by organizing and

promoting the I Am movement through the use of the mails. The

Held: charge was that certain designated corporations were formed,

literature distributed and sold, funds solicited, and memberships in

1. The only issue submitted to the jury by the District Court was the I Am movement sought "by means of false and fraudulent

whether respondents believed the representations to be true. representations, pretenses and promises." The false

P. 322 U. S. 84. representations charged were eighteen in number. It is sufficient at

this point to say that they covered respondents' alleged religious

2. Respondents did not acquiesce in the withdrawal from the jury of doctrines or beliefs. They were all set forth in the first count. The

the issue of the truth of their religious doctrines or beliefs, and are following are representative:

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 7 of 267

"that Guy W. Ballard, now deceased, alias Saint Germain, Jesus, persons intended to be defrauded, and to obtain from persons

George Washington, and Godfre Ray King, had been selected and intended to be defrauded by the defendants, money, property, and

thereby designated by the alleged 'ascertained masters,' Saint other things of value and to convert the same to the use and the

Germain, as a divine messenger, and that the words of 'ascended benefit of the defendants, and each of them;"

masters' and the words of the alleged divine entity, Saint Germain,

would be transmitted to mankind through the medium of the said The indictment contained twelve counts, one of which charged a

Guy W. Ballard;" conspiracy to defraud. The first count set forth all of the eighteen

representations, as we have said. Each of the other counts

"that Guy W. Ballard, during his lifetime, and Edna W. Ballard, and incorporated and realleged all of them and added no additional

Donald Ballard, by reason of their alleged high spiritual attainments ones. There was a demurrer and a motion to quash each of which

and righteous conduct, had been selected as divine messengers asserted, among other things, that the indictment attacked the

through which the words of the alleged 'ascended masters,' religious beliefs

including

Page 322 U. S. 81

Page 322 U. S. 80

of respondents and sought to restrict the free exercise of their

the alleged Saint Germain, would be communicated to mankind religion in violation of the Constitution of the United States. These

under the teachings commonly known as the 'I Am' movement;" motions were denied by the District Court. Early in the trial,

however, objections were raised to the admission of certain

"that Guy W. Ballard, during his lifetime, and Edna W. Ballard and evidence concerning respondents' religious beliefs. The court

Donald Ballard had, by reason of supernatural attainments, the conferred with counsel in absence of the jury and, with the

power to heal persons of ailments and diseases and to make well acquiescence of counsel for the United States and for respondents,

persons afflicted with any diseases, injuries, or ailments, and did confined the issues on this phase of the case to the question of the

falsely represent to persons intended to be defrauded that the good faith of respondents. At the request of counsel for both sides,

three designated persons had the ability and power to cure persons the court advised the jury of that action in the following language:

of those diseases normally classified as curable and also of

diseases which are ordinarily classified by the medical profession as "Now, gentlemen, here is the issue in this case:"

being incurable diseases, and did further represent that the three

designated persons had in fact cured either by the activity of one, "First, the defendants in this case made certain representations of

either, or all of said persons, hundreds of persons afflicted with belief in a divinity and in a supernatural power. Some of the

diseases and ailments;" teachings of the defendants, representations, might seem

extremely improbable to a great many people. For instance, the

Each of the representations enumerated in the indictment was appearance of Jesus to dictate some of the works that we have had

followed by the charge that respondents "well knew" it was false. introduced in evidence, as testified to here at the opening

After enumerating the eighteen misrepresentations the indictment transcription, or shaking hands with Jesus, to some people that

also alleged: might seem highly improbable. I point that out as one of the many

statements."

"At the time of making all of the afore-alleged representations by

the defendants, and each of them, the defendants, and each of "Whether that is true or not is not the concern of this Court and is

them, well knew that all of said aforementioned representations not the concern of the jury -- and they are going to be told so in

were false and untrue and were made with the intention on the part their instructions. As far as this Court sees the issue, it is

of the defendants, and each of them, to cheat, wrong, and defraud immaterial what these defendants preached or wrote or taught in

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 8 of 267

their classes. They are not going to be permitted to speculate on contend that the truth or verity of their religious doctrines or beliefs

the actuality of the happening of those incidents. Now, I think I should have been submitted to the jury. In their motion for new

have made that as clear as I can. Therefore, the religious beliefs of trial, they did contend, however, that the withdrawal of these

these defendants cannot be an issue in this court." issues from the jury was error because it was, in effect, an

amendment of the indictment. That was also one of their

"The issue is: did these defendants honestly and in good faith specifications of errors on appeal. And other errors urged on appeal

believe those things? If they did, they should be acquitted. I cannot included the overruling of the demurrer to the indictment and the

make it any clearer than that." motion to quash, and the

"If these defendants did not believe those things, they did not Page 322 U. S. 83

believe that Jesus came down and dictated,

disallowance of proof of the truth of respondents' religious

Page 322 U. S. 82 doctrines or beliefs.

or that Saint Germain came down and dictated, did not believe the The Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the judgment of conviction

things that they wrote, the things that they preached, but used the and granted a new trial, one judge dissenting. 138 F.2d 540. In its

mail for the purpose of getting money, the jury should find them view, the restriction of the issue in question to that of good faith

guilty. Therefore, gentlemen, religion cannot come into this case." was error. Its reason was that the scheme to defraud alleged in the

indictment was that respondents made the eighteen alleged false

The District Court reiterated that admonition in the charge to the representations, and that, to prove that defendants devised the

jury, and made it abundantly clear. The following portion of the scheme described in the indictment,

charge is typical:

"it was necessary to prove that they schemed to make some at

"The question of the defendants' good faith is the cardinal question least, of the [eighteen] representations . . . and that some, at least,

in this case. You are not to be concerned with the religious belief of of the representations which they schemed to make were false."

the defendants, or any of them. The jury will be called upon to pass

on the question of whether or not the defendants honestly and in 138 F.2d 545. One judge thought that the ruling of the District Court

good faith believed the representations which are set forth in the was also error because it was "as prejudicial to the issue of honest

indictment, and honestly and in good faith believed that the belief as to the issue of purposeful misrepresentation." Id., p. 546.

benefits which they represented would flow from their belief to

those who embraced and followed their teachings, or whether The case is here on a petition for a writ of certiorari which we

these representations were mere pretenses without honest belief granted because of the importance of the question presented.

on the part of the defendants or any of them, and, were the

representations made for the purpose of procuring money, and The United States contends that the District Court withdrew from

were the mails used for this purpose." the jury's consideration only the truth or falsity of those

representations which related to religious concepts or beliefs, and

As we have said, counsel for the defense acquiesced in this that there were representations charged in the indictment which

treatment of the matter, made no objection to it during the trial, fell within a different category. * The argument is that this latter

and indeed treated it without protest as the law of the case group of

throughout the proceedings prior to the verdict. Respondents did

not change their position before the District Court after verdict and Page 322 U. S. 84

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 9 of 267

representations was submitted to the jury, that they were adequate fairness to respondents, that principle cannot be applied here. The

to constitute an offense under the Act, and that they were real objection of respondents is not that the truth of their religious

supported by the requisite evidence. It is thus sought to bring the doctrines or beliefs should have been submitted to the jury. Their

case within the rule of Hall v. United States, 168 U. S. 632, 168 U. demurrer and motion to quash made clear their position that that

S. 639-640, which held that, where an indictment contained "all the issue should be withheld from the jury on the basis of the First

necessary averments to constitute an offense created by the Amendment. Moreover, their position at all times was, and still is,

statute," a conviction would not be set aside because a "totally that the court should have gone the whole way and withheld from

immaterial fact" was averred but not proved. We do not stop to the jury both that issue and the issue of their good faith. Their

ascertain the relevancy of that rule to this case, for we are of the demurrer and motion to quash asked for dismissal of the entire

view that all of the representations charged in the indictment which indictment. Their argument that the truth of their religious

related at least in part to the religious doctrines or beliefs of doctrines or beliefs should have gone to the jury when the question

respondents were withheld from the jury. The trial judge did not of their good faith was submitted was and is merely an alternative

differentiate them. He referred in the charge to the "religious argument. They never forsook their position that the indictment

beliefs" and "doctrines taught by the defendants" as matters should have been dismissed, and that none of it was good.

withheld from the jury. And, in stating that the issue of good faith Moreover, respondents' motion for new trial challenged the

was the "cardinal question" in the case, he charged, as already propriety of the action of the District Court in withdrawing from the

noted, that jury the issue of the truth of their religious doctrines or beliefs

without also withdrawing the question of their good faith. So we

"The jury will be called upon to pass on the question of whether or conclude that the rule of Johnson v. United States, supra, does not

not the defendants honestly and in good faith believed the prevent respondents from reasserting now that no part of the

representations which are set forth in the indictment." indictment should have been submitted to the jury.

Nowhere in the charge were any of the separate representations As we have noted, the Circuit Court of Appeals held that the

submitted to the jury. A careful reading of the whole charge leads question of the truth of the representations concerning

us to agree with the Circuit Court of Appeals on this phase of the

case that the only issue submitted to the jury was the question as Page 322 U. S. 86

stated by the District Court, of respondents' "belief in their

representations and promises." respondent's religious doctrines or beliefs should have been

submitted to the jury. And it remanded the case for a new trial. It

The United States contends that respondents acquiesced in the may be that the Circuit Court of Appeals took that action because it

withdrawal from the jury of the truth of their religious did not think that the indictment could be properly construed as

charging a scheme to defraud by means other than

Page 322 U. S. 85 misrepresentations of respondents' religious doctrines or beliefs. Or

that court may have concluded that the withdrawal of the issue of

doctrines or beliefs and that their consent bars them from insisting the truth of those religious doctrines or beliefs was unwarranted

on a different course once that one turned out to be unsuccessful. because it resulted in a substantial change in the character of the

Reliance for that position is sought in Johnson v. United States, 318 crime charged. But, on whichever basis that court rested its action,

U. S. 189. That case stands for the proposition that, apart from we do not agree that the truth or verity of respondents' religious

situations involving an unfair trial, an appellate court will not grant doctrines or beliefs should have been submitted to the jury.

a new trial to a defendant on the ground of improper introduction of Whatever this particular indictment might require, the First

evidence or improper comment by the prosecutor where the Amendment precludes such a course, as the United States seems

defendant acquiesced in that course and made no objection to it. In to concede. "The law knows no heresy, and is committed to the

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 10 of 267

support of no dogma, the establishment of no sect." Watson v. doctrines are subject to trial before a jury charged with finding their

Jones, 13 Wall. 679,80 U. S. 728. The First Amendment has a dual truth or falsity, then the same can be done with the religious beliefs

aspect. It not only "forestalls compulsion by law of the acceptance of any sect. When the triers of fact undertake that task, they enter

of any creed or the practice of any form of worship," but also a forbidden domain. The First Amendment does not select any one

"safeguards the free exercise of the chosen form of group or any one type of religion for preferred treatment. It puts

religion." Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 310 U. S. 303. them all in that position. Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105. As

stated in Davis v. Beason, 133 U. S. 333, 133 U. S. 342:

"Thus, the Amendment embraces two concepts -- freedom to

believe and freedom to act. The first is absolute but, in the nature "With man's relations to his Maker and the obligations he may think

of things, the second cannot be." they impose, and the manner in which an expression shall be made

by him of his belief on those subjects, no interference can be

Id., pp. 310 U. S. 303-304. Freedom of thought, which includes permitted, provided always the laws of society, designed to secure

freedom of religious belief, is basic in a society of free men. Board its peace and prosperity, and the morals of its people, are not

of Education by Barnette, 319 U. S. 624. It embraces the right to interfered with."

maintain theories of life and of death and of the hereafter which are

rank heresy to followers of the orthodox faiths. Heresy trials are See Prince

foreign to our Constitution. Men may believe what they cannot

prove. They may not be put to the proof of their religious doctrines Page 322 U. S. 88

or beliefs. Religious experiences which are as real as life to some

may be incomprehensible to others. v. Massachusetts, 321 U. S. 158. So we conclude that the District

Court ruled properly when it withheld from the jury all questions

Page 322 U. S. 87 concerning the truth or falsity of the religious beliefs or doctrines of

respondents.

Yet the fact that they may be beyond the ken of mortals does not

mean that they can be made suspect before the law. Many take Respondents maintain that the reversal of the judgment of

their gospel from the New Testament. But it would hardly be conviction was justified on other distinct grounds. The Circuit Court

supposed that they could be tried before a jury charged with the of Appeals did not reach those questions. Respondents may, of

duty of determining whether those teachings contained false course, urge them here in support of the judgment of the Circuit

representations. The miracles of the New Testament, the Divinity of Court of Appeals. Langnes v. Green, 282 U. S. 531, 282 U. S. 538-

Christ, life after death, the power of prayer are deep in the religious 539; Story Parchment Co. v. Paterson Co., 282 U. S. 555, 282 U. S.

convictions of many. If one could be sent to jail because a jury in a 560, 282 U. S. 567-568. But since attention was centered on the

hostile environment found those teachings false, little indeed would issues which we have discussed, the remaining questions were not

be left of religious freedom. The Fathers of the Constitution were fully presented to this Court either in the briefs or oral argument. In

not unaware of the varied and extreme views of religious sects, of view of these circumstances, we deem it more appropriate to

the violence of disagreement among them, and of the lack of any remand the cause to the Circuit Court of Appeals so that it may

one religious creed on which all men would agree. They fashioned a pass on the questions reserved. Lutcher & Moore Lumber Co. v.

charter of government which envisaged the widest possible Knight, 217 U. S. 257, 217 U. S. 267-268; Brown v. Fletcher, 237 U.

toleration of conflicting views. Man's relation to his God was made S. 583. If any questions of importance survive and are presented

no concern of the state. He was granted the right to worship as he here, we will then have the benefit of the views of the Circuit Court

pleased, and to answer to no man for the verity of his religious of Appeals. Until that additional consideration is had, we cannot be

views. The religious views espoused by respondents might seem sure that it will be necessary to pass on any of the other

incredible, if not preposterous, to most people. But if those constitutional issues which respondents claim to have reserved.

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 11 of 267

The judgment is reversed, and the cause is remanded to the Circuit 1. 2.MUNICIPAL TAX; RETAIL DEALERS IN GENERAL

Court of Appeals for further proceedings in conformity to this MERCHANDISE; ORDINANCE PRESCRIBING TAX NEED NOT

opinion. BE APPROVED BY THE' PRESIDENT TO BE EFFECTIVE.—The

business of "retail dealers in

Reversed.

387

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 387

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

[No. L-9637. April 30, 1957] 1. general merchandise" is expressly enumerated in subsection

AMERICAN BIBLE SOCIETY, plaintiff and appellant, vs. CITY (o), section 18 of Republic Act No. 409: hence. an

OF MANILA, defendant and appellee. ordinance prescribing a municipal tax on said business

1. 1.STATUTES; SIMULTANEOUS REPEAL AND RE- does not have to be approved by the President to be

ENACTMENT; EFFECT OF REPEAL UPON RIGHTS AND effective, as it is not among those businesses referred to in

LIABILITIES WHICH ACCRUED UNDER THE ORIGINAL subsection (ii) Section 18 of the same Act subject to the

STATUTE.—Where the old statute is repealed in its entirety approval of the President.

and by the same enactment re-enacts all or certain

portions of the pre-existing law, the majority view holds

1. 3.CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; RELIGIOUS

that the rights and liabilities which. have accrued under the

FREEDOM; DlSSEMINATION OF RELIGIOUS INFORMATION,

original statute are preserved and may be enforced, since

WHEN MAY BE RESTRAINED; PAYMENT OF LlCENSE FEE,

the re-enactment neutralizes the repeal, therefore

IMPAIRS FREE EXERCISE OF RELIGION.—The consti-tutional

continuing the law in force without interruption. (Crawford,

guaranty of the free exercise and enjoyment of religious

Statutory Construction, Sec. 322). In the case at bar,

profession and worship carries with it the right to

Ordinances Nos. 2529 and 3000 of the City of Manila were

disseminate religious information. Any restraint of such

enacted by the Municipal Board of the City of Manila by

right can only be justified like other restraints of freedom of

virtue of the power granted to it by section 2444,

expression on the grounds that there is a clear and present

Subsection (m-2) of the Revised Administrative Code,

danger of any substantive evil which the State has the

superseded on June 18, 1949, by section 18, Subsection (o)

right to prevent." (Tañada and Fernando on the Constitution

of Republic Act No. 409, known as the Revised Charter of

of the Philippines, Vol. I, 4th ed., p. 297). In the case at bar,

the City of Manila. The only essential difference between

plaintiff is engaged in the distribution and sales of bibles

these two provisions is that while Subsection (m-

and religious articles. The City Treasurer of Manila informed

2) prescribes that the combined total tax of any dealer or

the plaintiff that it was conducting the business of general

manufacturer, or both, enumerated under Subsections (m-

merchandise without providing itself with the necessary

1) and (m-2), whether dealing in one or all of the articles

Mayor's permit and municipal license, in violation of

mentioned therein, shall not be in excess of P500 per

Ordinance No. 3000, as amended, and Ordinance No. 2529,

annum, the corresponding Section 18, subsection (o) of

as amended, and required plaintiff to secure the

Republic Act No. 409, does not contain any limitation as to

corresponding permit and license. Plaintiff protested

the amount of tax or license fee that the retail dealer has

against this requirement and claimed that it never made

to pay per annum. Hence, and in accordance with the

any profit from the sale of its bibles. Held: It is true the

weight of authorities aforementioned, City ordinances Nos.

price asked for the religious articles was in some instances

2529 and 3000 are still in force and effect.

a little bit higher than the actual cost of the same, but this

cannot mean that plaintiff was engaged in the business or

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 12 of 267

occupation of selling said "merchandise" for profit. For this Republic Act No. 409, known as the Revised Charter of the City of

reasons, the provisions of City Ordinance No. 2529, as Manila.

amended, which requires the payment of license fee for In the course of its ministry, plaintiff's Philippine agency has

conducting the business of general merchandise, cannot be been distributing and selling bibles and/or gospel portions thereof

applied to plaintiff society, for in doing so, it would impair (except during the Japanese occupation) throughout the Philippines

its free exercise and enjoyment of its religious profession and translating the same into several Philippine dialects. On May

and worship, as well as its rights of dissemination of 29, 1953, the acting City Treasurer of the City of Manila informed

religious beliefs. Upon the other hand, City Ordinance No. plaintiff that it was conducting the business of general merchandise

3000, as amended, which requires the obtention of the since November, 1945, without providing itself with the necessary

Mayor's permit before any person can engage in any of the Mayor's permit and municipal license, in violation of Ordinance No.

businesses, trades or occupations enumerated therein, 3000, as amended, and Ordinances Nos. 2529, 3028 and 3364, and

does not impose any charge upon the enjoyment of a right required plaintiff to secure, within three days, the corresponding

granted by the Constitution, nor tax the exercise of permit and license fees, together with compromise covering the

religious practices. Hence, it cannot be considered period from the 4th quarter of 1945 to the 2nd quarter of 1953, in

unconstitutional, even if applied to plaintiff Society. But as the total sum of P5,821.45 (Annex A).

Ordinance No. 2529 is not applicable to plain 389

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 389

388 American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

38 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED Plaintiff protested against this requirement, but the City Treasurer

8 demanded that plaintiff deposit and pay under protest the sum of

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila, P5,891.45, if suit was to be taken in court regarding the same

(Annex B). To avoid the closing of its business as well as f urther

1. tiff and the City of Manila is powerless to license or tax the

fines and penalties in the premises, on October 24, 1953, plaintiff

business of plaintiff society involved herein, for the reasons

paid to the defendant under protest the said permit and license

above stated, Ordinance No. 3000 is also inapplicable to

fees in the aforementioned amount, giving at the same time notice

said business, trade or occupation of the plaintiff.

to the City Treasurer that suit would be taken in court to question

the legality of the ordinances under which, the said fees were being

APPEAL from a judgment of the Court of First Instance of Manila. collected (Annex C), which was done on the same date by filing the

Bayona, J. complaint that gave rise to this action. In its complaint plaintiff

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court. prays that judgment be rendered declaring the said Municipal

City Fiscal Eugenio Angeles and Juan Nabong for appellant. Ordinance No. 3000, as amended, and Ordinances Nos. 2529, 3028

Assistant City Fiscal Arsenio Nañawa for appellee. and 3364 illegal and unconstitutional, and that the defendant be

ordered to refund to the plaintiff the sum of P5,891.45 paid under

FÉLIX, J.: protest, together with legal interest thereon, and the costs, plaintiff

further praying for such other relief and remedy as the court may

Plaintiff-appellant is a foreign, non-stock, non-profit, religious, deem just and equitable.

missionary corporation duly registered and doing business in the Defendant answered the complaint, maintaining in turn that said

Philippines through its Philippine agency established in Manila in ordinances were enacted by the Municipal Board of the City of

November, 1898, with its principal office at 636 Isaac Peral in said Manila by virtue of the power granted to it by section 2444,

City. The defendantappellee is a municipal corporation with powers subsection (m-2) of the Revised Administrative Code, superseded

that are to be exercised in conformity with the provisions of on June 18, 1949, by section 18, subsection (1) of Republic Act No.

409, known as the Revised Charter of the City of Manila, and

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 13 of 267

praying that the complaint be dismissed, with costs against Quarter Amoun

plaintiff. This answer was replied by the plaintiff reiterating the

t

unconstitutionality of the often-repeated ordinances.

Before trial the parties submitted the following stipulation of of

facts: Sales

"COME NOW the parties in the above-entitled case, thru their 1947 .....

undersigned attorneys and respectfully submit the following

stipulation of facts: 3rd quarter ....................................................... 14,654.13

1. That the plaintiff sold for the use of the purchasers at its 1947 ......

principal office at 636 Isaac Peral, Manila, Bibles, New Testaments, 4th quarter ....................................................... 12,590.94

390

1947 ......

390 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

1st quarter ....................................................... 11,143.90

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

1948 ......

bible portions and bible concordance in English and other foreign

languages imported by it from the United States as well as Bibles, 2nd quarter ....................................................... 14,715.26

New Testaments and bible portions in the local dialects imported 1948 ......

and/or purchased locally; that from the fourth quarter of 1945 to the 3rd quarter ....................................................... 38,333.83

first quarter of 1953 inclusive the sales made by the plaintiff were as 1948 ......

follows: 4th quarter ....................................................... 16,179.90

Quarter Amoun 1948 ......

t 1st quarter ....................................................... 23,975.10

of 1949 ......

Sales 2nd quarter ....................................................... 17,802.08

4th quarter ....................................................... P1,244.21 1949 ......

1945 ..... 3rd quarter ....................................................... 16,640.79

1st quarter ....................................................... 2,206.85 1949 ......

1946 ..... 4th quarter ....................................................... 15,961.38

2nd quarter ....................................................... 1,950.38 1949 ......

1946 ..... 1st quarter ....................................................... 18,562.46

3rd quarter ....................................................... 2,235.99 1950 ......

1946 ...... 2nd quarter ....................................................... 21,816.32

4th quarter ....................................................... 3,256.04 1950 ......

1946 ..... 3rd quarter ....................................................... 25,004.55

1st quarter ....................................................... 13,241.07 1950 ......

1947 ..... 4th quarter ....................................................... 45,287.92

2nd quarter ....................................................... 15,774.55 1950 ......

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 14 of 267

Quarter Amoun Bible Society in the United States pay any license fee or sales tax

for the sale of bible therein. Plaintiff further tried to establish that it

t

never made any profit from the sale of its bibles, which are

of disposed of for as low as one third of the cost, and that in order to

Sales maintain its operating cost it obtains substantial remittances from

1st quarter ....................................................... 37,841.21 its New York office and voluntary contributions and gifts from

certain churches, both in the United States and in the Philippines,

1951 ...... which are interested in its missionary work. Regarding plaintiff's

2nd quarter ....................................................... 29,103.98 contention of lack of profit in the sale of bibles, defendant retorts

1951 ...... that the admissions of plaintiff-appellant's lone witness who

testified on cross-examination that bibles bearing the price of 70

3rd quarter ....................................................... 20181.10 cents each from plaintiff-appellant's New York office are sold here

1951 ...... by plaintiff-appellant at P1.30 each; those bearing the price of

4th quarter ....................................................... 22,968.91 $4.50 each are sold here at P10 each; those bearing the price of $7

1951 ...... each are sold here at P15 each; and those bearing the price of $11

each are sold here at P22 each, clearly show that plaintiff's

1st quarter ....................................................... 23,002.65 contention that it never makes any profit from the sale of its bible,

1952 ...... is evidently untenable.

2nd quarter ....................................................... 17,626.96 After hearing the Court rendered judgment, the last part of

which is as follows:

1952 ...... "As may be seen from the repealed section (m-2) of the Revised

3rd quarter ....................................................... 17,921.01 Administrative Code and the repealing portions (o) of section 18 of

1952 ..... Republic Act No. 409, although they seemingly differ in the way the

legislative intent is expressed, yet their meaning is practically the

4th quarter ....................................................... 24 180 72 same for the purpose of taxing the merchandise mentioned in said

1952 ...... legal provisions, and that the taxes to be levied by said ordinances

1st quarter ....................................................... s29,516.21 is in the nature of percentage graduated taxes (Sec. 3 of Ordinance

1953 ...... No. 3000, as amended, and Sec. 1, Group 2, of Ordinance No. 2529,

as amended by Ordinance No. 3364).

2. That the parties hereby reserve the right to present evidence of

392

other facts not herein stipulated.

WHEREFORE, it is respectfully prayed that this case be set for 392 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

behalf. so the parties may present further evidence on their behalf. American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

(Record on Appeal, pp. 15-16)" IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS, this Court is of the

391 opinion and so holds that this case should be dismissed, as it is

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 391 hereby dismissed, for lack of merits, with costs against the

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila, plaintiff."

Not satisfied with this verdict plaintiff took up the matter to the

When the case was set for hearing, plaintiff proved, among other

Court of Appeals which certified the case to Us for the reason that

things, that it has been in existence in the Philippines since 1899,

the errors assigned to the lower Court involved only questions of

and that its parent society is in New York, United States of America;

law.

that its contiguous real properties located at Isaac Peral are exempt

Appellant contends that the lower Court erred:

from real estate taxes; and that it was never required to pay any

municipal license fee or tax before the war, nor does the American

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 15 of 267

1. 1.In holding that Ordinances Nos. 2529 and 3000, as ordinances in relation to their application to the sale of bibles, etc.

respectively amended, are not unconstitutional; by appellant. The records show that by letter of May 29, 1953

2. 2.In holding that subsection m-2 of Section 2444 of the (Annex A), the City Treasurer required plaintiff to secure a Mayor's

Revised Administrative Code under which Ordinances Nos. permit in connection with the society's alleged business of

2529 and 3000 were promulgated, was not repealed by distributing and selling bibles, etc. and to pay permit dues in the

Section 18 of Republic Act No. 409; sum of P35 for the period covered in this litigation, plus the sum of

P35 for compromise on account of plaintiffs failure to secure the

3. 3.In not holding that an ordinance providing for percentage permit required by Ordinance No.. 3000 of the City of Manila, as

taxes based on gross sales or receipts, in order to be valid amended. This Ordinance is of general application and not

under the new Charter of the City of Manila, must first be particularly directed against institutions like the plaintiff, and it

approved by the President of the Philippines; and does not contain any provisions whatsoever prescribing religious

censorship nor restraining the free exercise and enjoyment of any

4. 4.In holding that, as the sales made by the plaintiff- religious profession. Section 1 of Ordinance No. 3000 reads as

appellant have assumed commercial proportions, it cannot follows:

escape from the operation of said municipal ordinances "SEC. 1. PERMITS NECESSARY.—It shall be unlawful for any person

under the cloak of religious privilege. or entity to conduct or engage in any of the businesses, trades, or

occupations enumerated in Section 3 of this Ordinance or other

The issues.—As may be seen from the preceding statement of the businesses, trades, or occupations for which a permit is required

case, the issues involved in the present controversy may be for the proper supervision and enforcement of existing laws and

reduced to the following: (1) whether or not the ordinances of the ordinances governing the sanitation, security, and welfare of the

City of Manila, Nos. 3000, as amended, and 2529, 3028 and 3364, public and the health of the employees engaged in the business

are constitutional and valid; and (2) whether the provisions of said specified in said section 3 hereof, WITHOUT FIRST HAVING

ordinances are applicable or not to the case at bar. OBTAINED A PERMIT THEREFOR FROM THE MAYOR AND THE

Section 1, subsection (7) of Article III of the Constitution of the NECESSARY LICENSE FROM THE CITY TREASURER."

Republic of the Philippines, provides that: The business, trade or occupation of the plaintiff involved in this

"(7) No law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion, case is not particularly mentioned in Section

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, and the free exercise and 394

enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without 394 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed. No religion

test shall be required for the exercise of civil or political rights." American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

393 3 of the Ordinance, and the record does not show that a permit is

required therefor under existing laws and ordinances for the proper

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 393

supervision and enforcement of their provisions governing the

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila sanitation, security and welfare of the public and the health of the

Predicated on this constitutional mandate, plaintiff-appellant employees engaged in the business of the plaintiff. However,

contends that Ordinances Nos. 2529 and 3000, as respectively section 3 of Ordinance 3000 contains item No. 79, which reads as

amended, are unconstitutional and illegal in so far as its society is follows:

concerned, because they provide for religious censorship and "79. All other businesses, trades or occupations not mentioned in

restrain the free exercise and enjoyment of its religious profession, this Ordinance, except those upon which the City is not empowered

to wit: the distribution and sale of bibles and other religious to license or to tax .... P5.00"

literature to the people of the Philippines. Therefore, the necessity of the permit is made to depend upon the

Before entering into a discussion of the constitutional aspect of power of the City to license or tax said business, trade or

the case, We shall first consider the provisions of the questioned occupation.

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 16 of 267

As to the license fees that the Treasurer of the City of Manila dealers exclusively engaged in the sale of (a) textiles * * * (e)

required the society to pay from the 4th quarter of 1945 to the 1st books, including stationery, paper and office supplies, * * *:

quarter of 1953 in the sum of P5,821.45, including the sum of P50 PROVIDED, HOWEVER, That the combined total tax of any debtor or

as compromise, Ordinance No. 2529, as amended by Ordinances manufacturer, or both, enumerated under these subsections (m-1)

Nos. 2779, 2821 and 3028 prescribes the following: and (m-2), whether dealing in one or all of the articles mentioned

"SEC. 1. FEES.—Subject to the provisions of section 578 of the herein, SHALL NOT BE IN EXCESS OF FIVE HUNDRED PESOS PER

Revised Ordinances of the City of Manila, as amended, there shall ANNUM."

be paid to the City Treasurer for engaging in any of the businesses and appellee's counsel maintains that City Ordinances Nos. 2529

or occupations below enumerated, quarterly, license fees based on and 3000, as amended, were enacted in virtue of the power that

gross sales or receipts realized during the preceding quarter in said Act No. 3669 conferred upon the City of Manila. Appellant,

accordance with the rates herein prescribed: PROVIDED, HOWEVER, however, contends that said ordinances are no longer in force and

That a person engaged in any business or occupation for the first effect as the law under which they were promulgated has been

time shall pay the initial license fee based on the probable gross expressly repealed by Section 102 of Republic Act No. 409 passed

sales or receipts for the first quarter beginning from the date of the on June 18, 1949,known as the Revised Manila Charter.

opening of the business as indicated herein for the corresponding Passing upon this point the lower Court categorically stated that

business or occupation. Republic Act No. 409 expressly repealed the provisions of Chapter

* * * * * * * 60 of the Revised Administrative Code but in the opinion of the trial

GROUP 2.—Retail dealers in new (not yet used) merchandise, Judge, although Section 2444 (m-2) of the former Manila Charter

which dealers are not yet subject to the payment of any municipal and section 18 (o) of the new seemingly differ in the way the

tax, such as (1) retail dealers in general merchandise; (2) retail legislative intent was expressed, yet their meaning is practically

dealers exclusively engaged in the sale of * * * books, including 396

stationery. 396 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

* * * * * * *

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

395

the same for the purpose of taxing the merchandise mentioned in

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 395 both legal provisions and, consequently, Ordinances Nos. 2529 and

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila, 3000, as amended, are to be considered as still in full force and

As may be seen, the license fees required to be paid quarterly in effect uninterruptedly up to the present.

Section 1 of said Ordinance No. 2529, as amended, are not "Often the legislature, instead of simply amending the preexisting

imposed directly upon any religious institution but upon those statute, will repeal the old statute in its entirety and by the same

engaged in any of the business or occupations therein enumerated, enactment re-enact all or certain portions of the preexisting law. Of

such as retail "dealers in general merchandise" which, it is alleged, course, the problem created by this sort of legislative action

cover the business or occupation of selling bibles, books, etc. involves mainly the effect of the repeal upon rights and liabilities

Chapter 60 of the Revised Administrative Code which includes which accrued under the original statute. Are those rights and

section 2444, subsection (m-2) of said legal body, as amended by liabilities destroyed or preserved? The authorities are divided as to

Act No. 3659, approved on December 8, 1929, empowers the the effect of simultaneous repeals and re-enactments. Some

Municipal Board of the City of Manila: adhere to the view that the rights and liabilities accrued under the

"(M-2) To tax and fix the license fee on (a) dealers in new repealed act are destroyed, since the statutes from which they

automobiles or accessories or both, and (b) retail dealers in new sprang are actually terminated, even though for only a very short

(not yet used) merchandise, which dealers are not yet subject to period of time. Others, and they seem to be in the majority, refuse

the payment of any municipal tax. to accept this view of the situation, and consequently maintain that

"For the purpose of taxation, these retail dealers shall be all rights and liabilities which have accrued under the original

classified as (1) retail dealers in general merchandise, and (2) retail statute are preserved and may be enforced, since the re-

CONSTI 2 CASES Free Exercise of Religion Page 17 of 267

enactment neutralizes the repeal, therefore continuing the law in and in accordance with the weight of the authorities above referred

force without interruption". (Crawford—Statutory Construction, Sec. to that maintain that "all rights and liabilities which have accrued

322). under the original statute are preserved and may be enforced,,

Appellant's counsel states that section 18 (o) of Republic Act No. since the reenactment neutralizes the repeal, therefore continuing

409 introduces a new and wider concept of taxation and is so the law in force without interruption", We hold that the questioned

different from the provisions of Section 2444 (m-2) that the former ordinances of the City of Manila are still in force and effect.

cannot be considered as a substantial re-enactment of the Plaintiff, however, argues that the questioned ordinances, to be

provisions of the latter. We have quoted above the provisions of valid, must first be approved by the President of the Philippines as

section 2444 (m-2) of the Revised Administrative Code and We shall per section 18, subsection (ii) of Republic Act No. 409, which reads

now copy hereunder the provisions of Section 18, subdivision (o) of as follows:

Republic Act No. 409, which reads as follows: "(ii) To tax, license and regulate any business, trade or occupation

"(o) To tax and fix the license fee on dealers in general being conducted within the City of Manila, not otherwise

merchandise, including importers and indentors, except those enumerated in the preceding subsections, including percentage

dealers who may be expressly subject to the payment of some taxes based on gross sales or receipts, subject to the approval of

other municipal tax under the provisions of this section. the PRESIDENT, except amusement taxes"

Dealers in general merchandise shall be classified as (a) but this requirement of the President's approval was not contained

wholesale dealers and (b) retail dealers. For purposes of the tax on in section 2444 of the former Charter of the

retail dealers, general merchandise shall be classified into four 398

main classes: namely (1) luxury articles, (2) semi-luxury articles, 398 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

(3) essential commodities, and (4) miscellaneous articles. A

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila

separate

397 City of Manila under which Ordinance No. 2529 was promulgated.

Anyway, as stated by appellee's counsel, the business of "retail

VOL. 101, APRIL 30, 1957 397 dealers in general merchandise" is expressly enumerated in

American Bible Society vs. City of Manila subsection (o), section 18 of Republic Act No. 409; hence, an

license shall be prescribed for each class but where commodities of ordinance prescribing a municipal tax on said business does not

different classes are sold in the same establishment, it shall not be have to be approved by the President to be effective, as it is not

compulsory for the owner to secure more than one license if he among those referred to in said subsection (ii). Moreover, the

pays the higher or highest rate of tax prescribed by ordinance. questioned ordinances are still in force, having been promulgated

Wholesale dealers shall pay the license tax as such, as may be by the Municipal Board of the City of Manila under the authority

provided by ordinance. granted to it by law.

For purposes of this section, the term 'General merchandise' The question that now remains to be determined is whether said

shall include poultry and livestock, agricultural products, fish and ordinances are inapplicable, invalid or unconstitutional if applied to

other allied products." the alleged business of distribution and sale of bibles to the people

The only essential difference that We find between these two of the Philippines by a religious corporation like the American Bible

provisions that may have any bearing on the case at bar, is that Society, plaintiff herein.

while subsection (m-2) prescribes that the combined total tax of With regard to Ordinance No. 2529, as amended by Ordinances

any dealer or manufacturer, or both, enumerated under Nos. 2779, 2821 and 3028, appellant contends that it is