Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Diabetes Care Standard 2010

Caricato da

Jose SanchezDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Diabetes Care Standard 2010

Caricato da

Jose SanchezCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Introduction

T

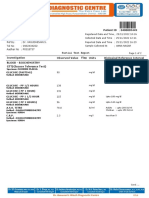

he American Diabetes Association Table 1—ADA evidence-grading system for clinical practice recommendations

(ADA) has been actively involved in

the development and dissemination

Level of

of diabetes care standards, guidelines,

evidence Description

and related documents for many years.

These statements are published in one or A Clear evidence from well-conducted, generalizable, randomized controlled trials

more of the Association’s professional that are adequately powered, including:

journals. This supplement contains the 䡠 Evidence from a well-conducted multicenter trial

latest update of ADA’s major position 䡠 Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in the analysis

statement, “Standards of Medical Care in Compelling nonexperimental evidence, i.e., the “all or none” rule developed by the

Diabetes,” which contains all of the Asso- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford

ciation’s key recommendations. In addi- Supportive evidence from well-conducted randomized controlled trials that are

tion, contained herein are selected position adequately powered, including:

statements on certain topics not adequately 䡠 Evidence from a well-conducted trial at one or more institutions

covered in the “Standards.” ADA hopes that 䡠 Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in the analysis

this is a convenient and important resource

B Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies, including:

for all health care professionals who care for

䡠 Evidence from a well-conducted prospective cohort study or registry

people with diabetes.

䡠 Evidence from a well-conducted meta-analysis of cohort studies

ADA Clinical Practice Recommenda-

Supportive evidence from a well-conducted case-control study

tions consist of position statements that

represent official ADA opinion as denoted C Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studies, including:

by formal review and approval by the Pro- 䡠 Evidence from randomized clinical trials with one or more major or three or

fessional Practice Committee and the Ex- more minor methodological flaws that could invalidate the results

ecutive Committee of the Board of 䡠 Evidence from observational studies with high potential for bias (such as case

Directors. Consensus reports and system- series with comparison to historical controls)

atic reviews are not official ADA 䡠 Evidence from case series or case reports

recommendations; however, they are Conflicting evidence with the weight of evidence supporting the recommendation

produced under the auspices of the Asso-

ciation by invited experts. These publica- E Expert consensus or clinical experience

tions may be used by the Professional

and updated as needed. A list of recent sensus panel) of a scientific or medical

Practice Committee as source documents

position statements is included on p. S100 issue related to diabetes. Effective January

to update the “Standards.”

of this supplement. 2010, consensus statements are renamed

ADA has adopted the following defi-

nitions for its clinically related reports. Systematic review. A balanced review consensus reports. The category will also

and analysis of the literature on a scien- include task force, workgroup, and expert

ADA position statement. An official

tific or medical topic related to diabetes. committee reports. Consensus reports

point of view or belief of the ADA. Posi-

Effective January 2010, technical reviews will not have the Association’s name in-

tion statements are issued on scientific or

are replaced with systematic reviews, for cluded in the title or subtitle and will in-

medical issues related to diabetes. They

which a priori search and inclusion/ clude a disclaimer in the introduction

may be authored or unauthored and are

exclusion criteria are developed and pub- stating that any recommendations are not

published in ADA journals and other sci-

lished. The systematic review provides a ADA position. A consensus report is typ-

entific/medical publications as appropri-

scientific rationale for a position state- ically developed immediately following a

ate. Position statements must be reviewed

ment and undergoes critical peer review consensus conference at which presenta-

and approved by the Professional Practice

before submission to the Professional tions are made on the issue under review.

Committee and, subsequently, by the

Practice Committee for approval. A list The statement represents the panel’s col-

Executive Committee of the Board of Di-

of past technical reviews is included on

rectors. ADA position statements are lective analysis, evaluation, and opinion

page S97 of this supplement.

typically based on a systematic review at that point in time based in part on the

or other review of published literature. Consensus report. A comprehensive ex- conference proceedings. The need for a

They are reviewed on an annual basis amination by a panel of experts (i.e., con- consensus report arises when clinicians or

scientists desire guidance on a subject for

which the evidence is contradictory or in-

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

complete. Once written by the panel, a

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-S001. consensus report is not subject to subse-

© 2010 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons. quent review or approval and does not

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. represent official Association opinion. A

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S1

Introduction

list of recent consensus reports is in- education, disability, and, above all, pa- Curt D. Furberg, MD, PhD, has been a

cluded on p. S96 of this supplement. tients’ values and preferences, must also member of the data safety monitoring

The Association’s Professional Prac- be considered and may lead to different committee for Wyeth.

tice Committee is responsible for review- treatment targets and strategies. Also,

conventional evidence hierarchies, such Sheila Y. Garris, MD, FACP, has been a

ing ADA systematic reviews and position

as the one adapted by the ADA, may miss speaker for Takeda, Osient, Glaxo-

statements, as well as for overseeing revi-

some nuances that are important in dia- SmithKline, and Novartis and has been

sions of the latter as needed. Appointment

betes care. For example, while there is ex- a speaker and consultant for Merck,

to the Professional Practice Committee is

cellent evidence from clinical trials Forrest*, and Daiichi Sankyo.

based on excellence in clinical practice

and/or research. The committee com- supporting the importance of achieving Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, has been a con-

prises physicians, diabetes educators, and glycemic control, the optimal way to sultant/advisor for Takeda, Merck*,

registered dietitians who have expertise in achieve this result is less clear. It is diffi- Amylin, Daiichi Sankyo, and

a range of areas, including adult and pe- cult to assess each component of such a Medtronic; has accepted honoraria

diatric endocrinology, epidemiology, and complex intervention. from Novo Nordisk; and has received

public health, lipid research, hyperten- ADA will continue to improve and research funding from Eli Lilly*;

sion, and preconception and pregnancy update the Clinical Practice Recommen- Takeda, Merck, Amylin, and Boehringer

care. All members of the Professional dations to ensure that clinicians, health Ingelheim have provided educational

Practice Committee are required to dis- plans, and policymakers can continue to grants* to Yale University for work con-

close potential conflicts of interest (listed rely on them as the most authoritative and ducted by him.

below). current guidelines for diabetes care. Our

Clinical Practice Recommendations are Wahida Karmally, DrPH, RD, CDE,

Grading of scientific evidence. There also available on the Association’s website CLS, reports no duality of interest.

has been considerable evolution in the eval- at www.diabetes.org/diabetescare.

uation of scientific evidence and in the de- Antoinette Moran, MD, has been on the

velopment of evidence-based guidelines advisory committee for Bayer.

since the ADA first began publishing prac- DUALITIES OF INTEREST Peter D. Reaven, MD, has received re-

tice guidelines. Accordingly, we developed search support from Takeda* and Amy-

a classification system to grade the quality Professional Practice Committee lin*, is a member of the speaker’s

of scientific evidence supporting ADA Members bureau for Merck, and is on the advisory

recommendations for all new and revised John E. Anderson, MD, is on the speaker’s panel of and is a board member for Bris-

ADA position statements. bureau for Amylin/Eli Lilly*, Glaxo- tol-Myers Squibb.

Recommendations are assigned rat- SmithKline*, Daichi/Sankyo, and Novo

ings of A, B, or C, depending on the qual- Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, has received

Nordisk. research funding from sanofi-aventis*,

ity of evidence (Table 1). Expert opinion

(E) is a separate category for recommen- Joan Bardsley, RN, MBA, CDE, has re- Novo Nordisk*, Takeda*, and Eli

dations in which there is as yet no evi- ceived research funding from Novo Nor- Lilly*.

dence from clinical trials, in which disk*, has received honoraria from Novo Craig Williams, PharmD, has received

clinical trials may be impractical, or in Nordisk* and GlaxoSmithKline*, and research funding from Merck* and

which there is conflicting evidence. Rec- owns stock in Pfizer* and Amylin. speaker fees from Merck/Schering

ommendations with an “A” rating are Plough and has a relative employed by

John B. Buse, MD, PhD, has conducted

based on large well-designed clinical trials Pfizer.

research and/or consulted under con-

or well-done meta-analyses. Generally,

tract between the University of North David F. Williamson, PhD, reports no

these recommendations have the best

Carolina and Amylin*, Bayhill Thera- duality of interest.

chance of improving outcomes when

peutics, Becton Dickinson*, Bristol-

applied to the population to which they Peter Wilson, MD, has received research

Myers Squibb*, DexCom*, Eli Lilly*,

are appropriate. Recommendations funding from GlaxoSmithKline*.

GI Dynamics, GlaxoSmithKline*,

with lower levels of evidence may be

Halozyme*, Hoffman-LaRoche*, In- Carol H. Wysham, MD, has been a

equally important but are not as well

terkrin*, Johnson & Johnson*, Lipo- speaker for Eli Lilly*, Merck, Novo

supported. The level of evidence sup-

Science*, Mannkind*, Medtronic*, Nordisk, and sanofi-aventis and a con-

porting a given recommendation is

Merck*, Novartis*, Novo Nordisk*, sultant and speaker for Amylin Pharma-

noted either as a heading for a group of

Osiris*, Pfizer*, sanofi-aventis*, Tol- ceuticals*.

recommendations or in parentheses af-

erex*, Transition Therapeutics*, and

ter a given recommendation.

Wyeth; and owns stock in Insulet*.

Of course, evidence is only one com- American Diabetes Association Staff

ponent of clinical decision-making. Clini- Martha Funnell, MS, RN, CDE, has been M. Sue Kirkman, MD, and Stephanie A.

cians care for patients, not populations; on the advisory board for Novo Nor- Dunbar, MPH, RD, report no duality of

guidelines must always be interpreted disk, Eli Lilly, HDI Diagnostics, Intuity interest.

with the needs of the individual patient in Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mann-

mind. Individual circumstances, such as kind and has been a consultant for ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

comorbid and coexisting diseases, age, sanofi-aventis. *Amount ⬎$10,000/year.

S2 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

S U M M A R Y O F R E V I S I O N S

Summary of Revisions for the 2010

Clinical Practice Recommendations

B

eginning with the 2005 supple- Revisions to the “Standards of The section “Diabetes self-management

ment, the Clinical Practice Recom- Medical Care in Diabetes” education” has been extensively revised

mendations contained only the In addition to many small changes related to reflect new evidence.

“Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” to new evidence since the previous ver- ● The section “Antiplatelet agents” has

and selected other position statements. sion, the following sections have under- been extensively revised to reflect re-

This change was made to emphasize the gone major changes: cent trials questioning the benefit of as-

importance of the “Standards” as the best pirin for primary cardiovascular disease

source to determine American Diabetes ● The section “Diagnosis of diabetes” has prevention in moderate- or low-risk

Association recommendations. The posi- been revised to include the use of A1C patients. The recommendation has

tion statements in the supplement are up- to diagnose diabetes, with a cut point of changed to consider aspirin therapy as

dated yearly. Position statements not ⱖ6.5%. a primary prevention strategy in those

included in the supplement will be up- ● The section previously titled “Diagnosis with diabetes at increased cardiovascu-

dated as necessary and republished when of pre-diabetes” has been renamed

lar risk (10-year risk ⬎10%). This in-

updated. A list of the position statements “Categories of increased risk for diabe-

cludes men ⬎50 years of age or women

not included in this supplement appears tes.” In addition to impaired fasting glu-

on p. S100. cose and impaired glucose tolerance, an ⬎60 years of age with at least one ad-

A1C range of 5.7– 6.4% has been in- ditional major risk factor.

● The section “Retinopathy screening

cluded as a category of increased risk

Additions to the “Standards of for future diabetes. and treatment” has been updated to

Medical Care in Diabetes” ● The section “Detection and diagnosis of include a recommendation on use of

GDM” has been revised to discuss po- fundus photography as a screening

● A section on cystic fibrosis–related dia- tential future changes in the diagnosis strategy.

betes has been added. based on international consensus. ● The section “Diabetes care in the hospi-

tal” has been extensively revised to re-

flect new evidence calling into question

very tight glycemic control goals in crit-

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

ically ill patients.

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-S003 ●

© 2010 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly

The section “Strategies for improving

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons. diabetes care” has been extensively re-

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. vised to reflect newer evidence.

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S3

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

Executive Summary: Standards of Medical

Care in Diabetes—2010

Current criteria for the diagnosis of Detection and diagnosis of medical nutrition therapy (MNT)

diabetes gestational diabetes mellitus alone, SMBG may be useful as a guide to

● A1C ⱖ6.5%: The test should be per- ● Screen for gestational diabetes mellitus the success of therapy. (E)

formed in a laboratory using a method (GDM) using risk-factor analysis and, if ● To achieve postprandial glucose tar-

that is National Glycohemoglobin Stan- appropriate, the OGTT. (C) gets, postprandial SMBG may be appro-

dardization Program (NGSP) certified ● Women with GDM should be screened priate. (E)

and standardized to the Diabetes Control for diabetes 6 –12 weeks postpartum ● When prescribing SMBG, ensure that

and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay. and should be followed up with subse- patients receive initial instruction in,

● FPG ⱖ126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l): Fasting is quent screening for the development of and routine follow-up evaluation of,

defined as no caloric intake for at least diabetes or pre-diabetes. (E) SMBG technique and their ability to use

8 h. data to adjust therapy. (E)

● 2-h plasma glucose ⱖ200 mg/dl (11.1 Prevention of type 2 diabetes ● Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)

● Patients with IGT (A), IFG (E), or an in conjunction with intensive insulin

mmol/l) during an oral glucose tolerance

test (OGTT): The test should be per- A1C of 5.7– 6.4% (E) should be re- regimens can be a useful tool to lower

formed as described by the World Health ferred to an effective ongoing support A1C in selected adults (age ⬎25 years)

Organization using a glucose load con- program for weight loss of 5–10% of with type 1 diabetes. (A)

body weight and increase in physical ● Although the evidence for A1C-

taining the equivalent of 75 g anhydrous

activity to at least 150 min/week of lowering is less strong in children,

glucose dissolved in water.

● In a patient with classic symptoms of

moderate activity such as walking. teens, and younger adults, CGM may

● Follow-up counseling appears to be im- be helpful in these groups. Success cor-

hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis:

portant for success. (B) relates with adherence to ongoing use

a random plasma glucose ⱖ200 mg/dl ● Based on potential cost savings of dia- of the device. (C)

(11.1 mmol/l). betes prevention, such counseling ● CGM may be a supplemental tool to

should be covered by third-party pay- SMBG in those with hypoglycemia un-

Testing for diabetes in asymptomatic ors. (E) awareness and/or frequent hypoglyce-

patients ● In addition to lifestyle counseling, met- mic episodes. (E)

● Testing to detect type 2 diabetes and formin may be considered in those who

assess risk for future diabetes in asymp- are at very high risk for developing di- A1C

tomatic people should be considered in abetes (combined IFG and IGT plus ● Perform the A1C test at least two times

adults of any age who are overweight or other risk factors such as A1C ⬎6%, a year in patients who are meeting treat-

obese (BMI ⱖ25 kg/m2) and who have hypertension, low HDL cholesterol, el- ment goals (and who have stable glyce-

one or more additional risk factors for evated triglycerides, or family history of mic control). (E)

diabetes in a first-degree relative) and ● Perform the A1C test quarterly in pa-

diabetes (see Table 4 of Standards of

Medical Care in Diabetes—2010). In who are obese and under 60 years of tients whose therapy has changed or

those without these risk factors, testing age. (E) who are not meeting glycemic goals. (E)

● Monitoring for the development of di- ● Use of point-of-care testing for A1C al-

should begin at age 45 years. (B)

● If tests are normal, repeat testing should

abetes in those with pre-diabetes lows for timely decisions on therapy

should be performed every year. (E) changes, when needed. (E)

be carried out at least at 3-year intervals.

(E)

Glucose monitoring Glycemic goals in adults

● To test for diabetes or to assess risk of

● Self-monitoring of blood glucose ● Lowering A1C to below or around 7%

future diabetes, A1C, FPG , or 2-h 75-g (SMBG) should be carried out three or has been shown to reduce microvascu-

OGTT are appropriate. (B) more times daily for patients using mul- lar and neuropathic complications of

● In those identified with increased risk tiple insulin injections or insulin pump type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Therefore,

for future diabetes, identify and, if ap- therapy. (A) for microvascular disease prevention,

propriate, treat other cardiovascular ● For patients using less frequent insulin the A1C goal for nonpregnant adults in

disease (CVD) risk factors. (B) injections, noninsulin therapies, or general is ⬍7%. (A)

● In type 1 and type 2 diabetes, random-

ized controlled trials of intensive versus

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

standard glycemic control have not

shown a significant reduction in CVD

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-S004

© 2010 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly outcomes during the randomized por-

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons. tion of the trials. Long-term follow-up

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. of the DCCT and UK Prospective Dia-

S4 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

Executive Summary

betes Study (UKPDS) cohorts suggests dividuals who have or are at risk for Other nutrition recommendations

that treatment to A1C targets below or diabetes. (A) ● Sugar alcohols and nonnutritive sweet-

around 7% in the years soon after the ● For weight loss, either low-carbohy- eners are safe when consumed within

diagnosis of diabetes is associated with drate or low-fat calorie-restricted diets the acceptable daily intake levels estab-

long-term reduction in risk of macro- may be effective in the short-term (up lished by the Food and Drug Adminis-

vascular disease. Until more evidence to 1 year). (A) tration (FDA). (A)

becomes available, the general goal of ● For patients on low-carbohydrate diets, ● If adults with diabetes choose to use

⬍7% appears reasonable for many monitor lipid profiles, renal function, alcohol, daily intake should be limited

adults for macrovascular risk reduc- and protein intake (in those with ne- to a moderate amount (one drink per

tion. (B) phropathy) and adjust hypoglycemic day or less for adult women and two

● Subgroup analyses of clinical trials such drinks per day or less for adult men).

therapy as needed. (E)

as the DCCT and UKPDS and evidence ● Physical activity and behavior modifi- (E)

for reduced proteinuria in the AD- ● Routine supplementation with antioxi-

cation are important components of

VANCE trial suggest a small but incre- weight loss programs and are most dants, such as vitamins E and C and

mental benefit in microvascular helpful in maintenance of weight loss. carotene, is not advised because of lack

outcomes with A1C values closer to (B) of evidence of efficacy and concern re-

normal. Therefore, for selected individ- lated to long-term safety. (A)

ual patients, providers might reason- ● Benefit from chromium supplementa-

ably suggest even lower A1C goals than Primary prevention of diabetes tion in people with diabetes or obesity

the general goal of ⬍7%, if this can be ● Among individuals at high risk for de- has not been conclusively demon-

achieved without significant hypogly- veloping type 2 diabetes, structured strated and, therefore, cannot be rec-

cemia or other adverse effects of treat- programs emphasizing lifestyle ommended. (C)

ment. Such patients might include changes including moderate weight ● Individualized meal planning should

those with short duration of diabetes, loss (7% body weight) and regular include optimization of food choices

long life expectancy, and no significant physical activity (150 min/week), with to meet recommended dietary allow-

CVD. (B) dietary strategies including reduced ances (RDAs)/dietary reference intakes

● Conversely, less stringent A1C goals calories and reduced intake of dietary (DRIs) for all micronutrients. (E)

than the general goal of ⬍7% may be fat, can reduce the risk for developing

appropriate for patients with a history diabetes and are therefore recom- Bariatric surgery

of severe hypoglycemia, limited life ex- ● Bariatric surgery should be considered

mended. (A)

pectancy, advanced microvascular or ● Individuals at high risk for type 2 dia- for adults with BMI ⬎35 kg/m2 and

macrovascular complications, or exten- betes should be encouraged to achieve type 2 diabetes, especially if the diabe-

sive comorbid conditions and those the U.S. Department of Agriculture tes or associated comorbidities are dif-

with longstanding diabetes in whom (USDA) recommendation for dietary fi- ficult to control with lifestyle and

the general goal is difficult to attain de- ber (14 g fiber/1,000 kcal) and foods pharmacologic therapy. (B)

spite diabetes self-management educa- ● Patients with type 2 diabetes who have

containing whole grains (one-half of

tion, appropriate glucose monitoring, grain intake). (B) undergone bariatric surgery need life-

and effective doses of multiple glucose- long lifestyle support and medical

lowering agents including insulin. (C) monitoring. (E)

Dietary fat intake in diabetes ● Although small trials have shown gly-

management cemic benefit of bariatric surgery in pa-

Medical nutrition therapy ● Saturated fat intake should be ⬍7% of tients with type 2 diabetes and BMI of

General recommendations

● Individuals who have pre-diabetes or

total calories. (A) 30 –35 kg/m2, there is currently insuf-

● Reducing intake of trans fat lowers LDL ficient evidence to generally recom-

diabetes should receive individualized

cholesterol and increases HDL choles- mend surgery in patients with BMI ⬍35

medical nutrition therapy (MNT) as

terol (A); therefore, intake of trans fat kg/m2 outside of a research protocol.

needed to achieve treatment goals, pref-

should be minimized. (E) (E)

erably provided by a registered dietitian ● The long-term benefits, cost-effective-

familiar with the components of diabe-

ness, and risks of bariatric surgery in

tes MNT. (A) Carbohydrate intake in diabetes

● Because MNT can result in cost-savings

individuals with type 2 diabetes should

management be studied in well-designed random-

and improved outcomes (B), MNT ● Monitoring carbohydrate, whether by

ized controlled trials with optimal

should be covered by insurance and carbohydrate counting, exchanges, or medical and lifestyle therapy as the

other payors. (E) experience-based estimation, remains a comparator. (E)

key strategy in achieving glycemic con-

Energy balance, overweight, and trol. (A) Diabetes self-management education

obesity ● For individuals with diabetes, the use of ● People with diabetes should receive di-

● In overweight and obese insulin- the glycemic index and glycemic load abetes self-management education

resistant individuals, modest weight may provide a modest additional bene- (DSME) according to national stan-

loss has been shown to reduce insulin fit for glycemic control over that ob- dards when their diabetes is diagnosed

resistance. Thus, weight loss is recom- served when total carbohydrate is and as needed thereafter. (B)

mended for all overweight or obese in- considered alone. (B) ● Effective self-management and quality

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S5

Executive Summary

of life are the key outcomes of DSME awareness or one or more episodes of style dietary pattern including reducing

and should be measured and moni- severe hypoglycemia should be advised sodium and increasing potassium intake,

tored as part of care. (C) to raise their glycemic targets to strictly moderation of alcohol intake, and in-

● DSME should address psychosocial is- avoid further hypoglycemia for at least creased physical activity. (B)

sues, since emotional well-being is several weeks, to partially reverse hypo- ● Pharmacologic therapy for patients with

associated with positive diabetes out- glycemia unawareness and reduce risk diabetes and hypertension should be

comes. (C) of future episodes. (B) with a regimen that includes either an

● Because DSME can result in cost- ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor

savings and improved outcomes (B), Immunization blocker (ARB). If one class is not toler-

DSME should be reimbursed by third- ● Annually provide an influenza vaccine ated, the other should be substituted. If

party payors. (E) to all diabetic patients 6 months of age. needed to achieve blood pressure targets,

(C) a thiazide diuretic should be added to

Physical activity ● Administer pneumococcal polysaccha- those with an estimated glomerular filtra-

● People with diabetes should be advised ride vaccine to all diabetic patients ⱖ2 tion rate (GFR) (see below) ⱖ30 ml/min

to perform at least 150 min/week of years of age. A one-time revaccination is per 1.73 m2 and a loop diuretic for those

moderate-intensity aerobic physical ac- recommended for individuals ⬎64 with an estimated GFR ⬍30 ml/min per

tivity (50 –70% of maximum heart years of age previously immunized 1.73 m2. (C)

rate). (A) when they were ⬍65 years of age if the ● Multiple drug therapy (two or more

● In the absence of contraindications, vaccine was administered ⬎5 years agents at maximal doses) is generally

people with type 2 diabetes should be ago. Other indications for repeat vacci- required to achieve blood pressure tar-

encouraged to perform resistance train- nation include nephrotic syndrome, gets. (B)

ing three times per week. (A) chronic renal disease, and other immu- ● If ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics are

nocompromised states, such as after used, kidney function and serum potas-

Psychosocial assessment and care transplantation. (C) sium levels should be closely moni-

● Assessment of psychological and social tored. (E)

situation should be included as an on- Hypertension/blood pressure control ● In pregnant patients with diabetes and

going part of the medical management Screening and diagnosis chronic hypertension, blood pressure

of diabetes. (E) ● Blood pressure should be measured at target goals of 110 –129/65–79 mmHg

● Psychosocial screening and follow-up every routine diabetes visit. Patients are suggested in the interest of long-

should include, but is not limited to, found to have systolic blood pressure term maternal health and minimizing

attitudes about the illness, expectations ⱖ130 mmHg or diastolic blood pres- impaired fetal growth. ACE inhibitors

for medical management and out- sure ⱖ80 mmHg should have blood and ARBs are contraindicated during

comes, affect/mood, general and diabe- pressure confirmed on a separate day. pregnancy. (E)

tes-related quality of life, resources Repeat systolic blood pressure ⱖ130

(financial, social, and emotional), and mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ⱖ80 Dyslipidemia/lipid management

psychiatric history. (E) mmHg confirms a diagnosis of hyperten- Screening

● Screen for psychosocial problems such sion. (C) ● In most adult patients, measure fasting

as depression and diabetes-related dis- lipid profile at least annually. In adults

tress, anxiety, eating disorders, and Goals with low-risk lipid values (LDL choles-

cognitive impairment when self- ● Patients with diabetes should be treated terol ⬍100 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol

management is poor. (C) to a systolic blood pressure ⬍130 ⬎50 mg/dl, and triglycerides ⬍150

mmHg. (C) mg/dl), lipid assessments may be re-

Hypoglycemia ● Patients with diabetes should be treated

peated every 2 years. (E)

● Glucose (15–20 g) is the preferred to a diastolic blood pressure ⬍80

treatment for the conscious individual mmHg. (B)

with hypoglycemia, although any form Treatment recommendations and

of carbohydrate that contains glucose Treatment goals

may be used. If SMBG 15 min after ● Patients with a systolic blood pressure ● Lifestyle modification focusing on the

treatment shows continued hypoglyce- of 130 –139 mmHg or a diastolic blood reduction of saturated fat, trans fat, and

mia, the treatment should be repeated. pressure of 80 – 89 mmHg may be given cholesterol intake; increase of n-3 fatty

Once SMBG glucose returns to normal, lifestyle therapy alone for a maximum acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols/

the individual should consume a meal of 3 months, and then if targets are not sterols; weight loss (if indicated); and

or snack to prevent recurrence of hypo- achieved, be treated with addition of increased physical activity should be

glycemia. (E) pharmacological agents. (E) recommended to improve the lipid

● Glucagon should be prescribed for all ● Patients with more severe hypertension profile in patients with diabetes. (A)

individuals at significant risk of severe (systolic blood pressure ⱖ140 or dia- ● Statin therapy should be added to life-

hypoglycemia, and caregivers or family stolic blood pressure ⱖ90 mmHg) at style therapy, regardless of baseline

members of these individuals in- diagnosis or follow-up should receive lipid levels, for diabetic patients:

structed in its administration. Gluca- pharmacologic therapy in addition to ● with overt CVD. (A)

gon administration is not limited to lifestyle therapy. (A) ● without CVD who are over the age of

health care professionals. (E) ● Lifestyle therapy for hypertension con- 40 years and have one or more other

● Individuals with hypoglycemia un- sists of: weight loss if overweight, DASH- CVD risk factors. (A)

S6 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

Executive Summary

● For lower risk patients than the above ● Combination therapy with ASA (75– Treatment

(e.g., without overt CVD and under the 162 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/ ● In the treatment of the nonpregnant pa-

age of 40 years), statin therapy should day) is reasonable for up to a year after tient with micro- or macroalbuminuria,

be considered in addition to lifestyle an acute coronary syndrome. (B) either ACE inhibitors or ARBs should

therapy if LDL cholesterol remains be used. (A)

above 100 mg/dl or in those with mul- Smoking cessation ● While there are no adequate head-to-

tiple CVD risk factors. (E) ● Advise all patients not to smoke. (A) head comparisons of ACE inhibitors

● In individuals without overt CVD, the ● Include smoking cessation counseling and ARBs, there is clinical trial support

primary goal is an LDL cholesterol and other forms of treatment as a rou- for each of the following statements:

⬍100 mg/dl (2.6 mmol/l). (A) tine component of diabetes care. (B) ● In patients with type 1 diabetes with

● In individuals with overt CVD, a lower hypertension and any degree of albu-

LDL cholesterol goal of ⬍70 mg/dl (1.8 Coronary heart disease minuria, ACE inhibitors have been

mmol/l), using a high dose of a statin, is Screening shown to delay the progression of ne-

an option. (B) ● In asymptomatic patients, evaluate risk phropathy. (A)

● If drug-treated patients do not reach the factors to stratify patients by 10-year ● In patients with type 2 diabetes, hy-

above targets on maximal tolerated sta- risk, and treat risk factors accordingly. pertension, and microalbuminuria,

tin therapy, a reduction in LDL choles- (B) both ACE inhibitors and ARBs have

terol of ⬃30 – 40% from baseline is an been shown to delay the progression

alternative therapeutic goal. (A) Treatment to macroalbuminuria. (A)

● Triglycerides levels ⬍150 mg/dl (1.7 ● In patients with known CVD, ACE in- ● In patients with type 2 diabetes, hy-

mmol/l) and HDL cholesterol ⬎40 hibitor (C) and aspirin and statin ther- pertension, macroalbuminuria, and

mg/dl (1.0 mmol/l) in men and ⬎50 apy (A) (if not contraindicated) should renal insufficiency (serum creatinine

mg/dl (1.3 mmol/l) in women are desir- be used to reduce the risk of cardiovas- ⬎1.5 mg/dl), ARBs have been shown

able. However, LDL cholesterol– cular events. to delay the progression of nephrop-

targeted statin therapy remains the ● In patients with a prior myocardial in- athy. (A)

preferred strategy. (C) farction, B-blockers should be contin- ● If one class is not tolerated, the other

● If targets are not reached on maximally ued for at least 2 years after the event. should be substituted. (E) Reduction of

tolerated doses of statins, combination (B) protein intake to 0.8 –1.0 g 䡠 kg body

therapy using statins and other lipid- ● Longer term use of B-blockers in the wt–1 䡠 day–1 in individuals with diabetes

lowering agents may be considered to absence of hypertension is reasonable if and the earlier stages of CKD and to

achieve lipid targets but has not been well tolerated, but data are lacking. (E) 0.8 g 䡠 kg body wt–1 䡠 day–1 in the later

evaluated in outcome studies for either ● Avoid TZD treatment in patients with stages of CKD may improve measures

CVD outcomes or safety. (E) symptomatic heart failure. (C) of renal function (urine albumin excre-

● Statin therapy is contraindicated in ● Metformin may be used in patients with tion rate, GFR) and is recommended.

pregnancy. (E) stable congestive heart failure (CHF) if (B)

renal function is normal. It should be ● When ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuret-

Antiplatelet agents avoided in unstable or hospitalized pa- ics are used, monitor serum creatinine

● Consider aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/ tients with CHF. (C) and potassium levels for the develop-

day) as a primary prevention strategy in ment of acute kidney disease and hy-

those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes at Nephropathy screening and perkalemia. (E)

increased cardiovascular risk (10-year treatment ● Continued monitoring of urine albu-

risk ⬎10%). This includes most men General recommendations min excretion to assess both response

⬎50 years of age or women ⬎60 years ● To reduce the risk or slow the progres- to therapy and progression of disease is

of age who have at least one additional sion of nephropathy, optimize glucose recommended. (E)

major risk factor (family history of control. (A) ● Consider referral to a physician ex-

CVD, hypertension, smoking, dyslipi- ● To reduce the risk or slow the progres- perienced in the care of kidney dis-

demia, or albuminuria). (C) sion of nephropathy, optimize blood ease when there is uncertainty about

● There is not sufficient evidence to rec- pressure control. (A) the etiology of kidney disease (active

ommend aspirin for primary preven- urine sediment, absence of retinopathy,

tion in lower risk individuals, such as Screening rapid decline in GFR), difficult manage-

men ⬍50 years of age or women ⬍60 ● Perform an annual test to assess urine ment issues, or advanced kidney dis-

years of age without other major risk albumin excretion in type 1 diabetic pa- ease. (B)

factors. In patients in these age-groups tients with diabetes duration of ⱖ5

with multiple other risk factors, clinical years and in all type 2 diabetic patients

judgment is required. (C) starting at diagnosis. (E) Retinopathy screening and treatment

● Use aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) ● Measure serum creatinine at least annu- General recommendations

as a secondary prevention strategy in ally in all adults with diabetes regard- ● To reduce the risk or slow the progres-

those with diabetes with a history of less of the degree of urine albumin sion of retinopathy, optimize glycemic

CVD. (A) excretion. The serum creatinine should control. (A)

● For patients with CVD and docu- be used to estimate GFR and stage the ● To reduce the risk or slow the progres-

mented aspirin allergy, clopidogrel (75 level of chronic kidney disease (CKD), sion of retinopathy, optimize blood

mg/day) should be used. (B) if present. (E) pressure control. (A)

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S7

Executive Summary

Screening not increase the risk of retinal hemor- ● Consider age when setting glycemic

● Adults and children aged 10 years or rhage. (A) goals in children and adolescents with

older with type 1 diabetes should have type 1 diabetes, with less stringent goals

an initial dilated and comprehensive Neuropathy screening and treatment for younger children. (E)

eye examination by an ophthalmologist ● All patients should be screened for dis-

or optometrist within 5 years after the tal symmetric polyneuropathy (DPN) at Nephropathy

onset of diabetes. (B) diagnosis and at least annually thereaf- ● Annual screening for microalbumin-

● Patients with type 2 diabetes should ter, using simple clinical tests. (B) uria, with a random spot urine sample

have an initial dilated and comprehen- ● Electrophysiological testing is rarely for microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio,

sive eye examination by an ophthalmol- needed, except in situations where the should be initiated once the child is 10

ogist or optometrist shortly after the clinical features are atypical. (E) years of age and has had diabetes for 5

diagnosis of diabetes. (B) ● Screening for signs and symptoms of years. (E)

● Subsequent examinations for type 1 cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy ● Confirmed, persistently elevated mi-

and type 2 diabetic patients should should be instituted at diagnosis of type croalbumin levels on two additional

be repeated annually by an ophthal- 2 diabetes and 5 years after the diagno- urine specimens should be treated with

mologist or optometrist. Less-frequent sis of type 1 diabetes. Special testing is an ACE inhibitor, titrated to normaliza-

exams (every 2–3 years) may be consid- rarely needed and may not affect man- tion of microalbumin excretion if pos-

ered following one or more normal eye agement or outcomes. (E) sible. (E)

exams. Examinations will be required ● Medications for the relief of specific

more frequently if retinopathy is pro- symptoms related to DPN and auto- Hypertension

gressing. (B) nomic neuropathy are recommended, ● Treatment of high-normal blood pres-

● High-quality fundus photographs can as they improve the quality of life of the sure (systolic or diastolic blood pres-

detect most clinically significant dia- patient. (E) sure consistently above the 90th

betic retinopathy. Interpretation of the percentile for age, sex, and height)

images should be performed by a Foot care should include dietary intervention

trained eye care provider. While retinal ● For all patients with diabetes, perform and exercise, aimed at weight control

photography may serve as a screening an annual comprehensive foot exami- and increased physical activity, if ap-

tool for retinopathy, it is not a substi- nation to identify risk factors predictive propriate. If target blood pressure is not

tute for a comprehensive eye exam, of ulcers and amputations. The foot ex- reached with 3– 6 months of lifestyle

which should be performed at least ini- amination should include inspection, intervention, pharmacologic treatment

tially and at intervals thereafter as rec- assessment of foot pulses, and testing should be initiated. (E)

ommended by an eye care professional. for loss of protective sensation (10-g ● Pharmacologic treatment of hyperten-

(E) monofilament plus testing any one of: sion (systolic or diastolic blood pres-

● Women with preexisting diabetes who vibration using 128-Hz tuning fork, sure consistently above the 95th

are planning pregnancy or who have pinprick sensation, ankle reflexes, or percentile for age, sex, and height or

become pregnant should have a com- vibration perception threshold). (B) consistently greater than 130/80

prehensive eye examination and be ● Provide general foot self-care education mmHg, if 95% exceeds that value)

counseled on the risk of development to all patients with diabetes. (B) should be initiated as soon as the diag-

and/or progression of diabetic retinop- ● A multidisciplinary approach is recom- nosis is confirmed. (E)

athy. Eye examination should occur in mended for individuals with foot ulcers ● ACE inhibitors should be considered

the first trimester with close follow-up and high-risk feet, especially those with for the initial treatment of hyperten-

throughout pregnancy and for 1 year a history of prior ulcer or amputation. sion. (E)

postpartum. (B) (B) ● The goal of treatment is a blood pres-

● Refer patients who smoke, have loss of sure consistently ⬍130/80 or below the

protective sensation and structural ab- 90th percentile for age, sex, and height,

Treatment normalities, or have history of prior whichever is lower. (E)

● Promptly refer patients with any level of lower-extremity complications to foot

macular edema, severe nonproliferative care specialists for ongoing preventive Dyslipidemia

diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), or any care and life-long surveillance. (C) Screening

proliferative diabetic retinopathy ● Initial screening for peripheral artery ● If there is a family history of hypercho-

(PDR) to an ophthalmologist who is disease (PAD) should include a history lesterolemia (total cholesterol ⬎240

knowledgeable and experienced in the for claudication and an assessment of mg/dl) or a cardiovascular event before

management and treatment of diabetic the pedal pulses. Consider obtaining an age 55 years, or if family history is un-

retinopathy. (A) ankle-brachial index (ABI), as many pa- known, then a fasting lipid profile

● Laser photocoagulation therapy is indi- tients with PAD are asymptomatic. (C) should be performed on children ⬎2

cated to reduce the risk of vision loss in ● Refer patients with significant claudica- years of age soon after diagnosis (after

patients with high-risk PDR, clinically tion or a positive ABI for further vascu- glucose control has been established).

significant macular edema, and in some lar assessment and consider exercise, If family history is not of concern, then

cases of severe NPDR. (A) medications, and surgical options. (C) the first lipid screening should be per-

● The presence of retinopathy is not a formed at puberty (ⱖ10 years). All chil-

contraindication to aspirin therapy for Children and adolescents dren diagnosed with diabetes at or after

cardioprotection, as this therapy does Glycemic control puberty should have a fasting lipid pro-

S8 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

Executive Summary

file performed soon after diagnosis Hypothyroidism ● Screening for diabetes complications

(after glucose control has been estab- ● Children with type 1 diabetes should be should be individualized in older

lished). (E) screened for thyroid peroxidase and adults, but particular attention should

● For both age-groups, if lipids are abnor- be paid to complications that would

thyroglobulin antibodies at diagnosis.

mal, annual monitoring is recom- (E) lead to functional impairment. (E)

mended. If LDL cholesterol values are ● TSH concentrations should be mea-

within the accepted risk levels (⬍100 sured after metabolic control has Diabetes care in the hospital

mg/dl [2.6 mmol/l]), a lipid profile been established. If normal, they ● All patients with diabetes admitted to

should be repeated every 5 years. (E) should be rechecked every 1–2 years, the hospital should have their diabetes

or if the patient develops symptoms clearly identified in the medical record.

Treatment of thyroid dysfunction, thyromegaly, (E)

● Initial therapy should consist of optimi- or an abnormal growth rate. Free T4 ● All patients with diabetes should have

zation of glucose control and MNT should be measured if TSH is abnor- an order for blood glucose monitoring,

using a Step II American Heart Associ- mal. (E) with results available to all members of

ation diet aimed at a decrease in the the health care team. (E)

amount of saturated fat in the diet. (E) Preconception care ● Goals for blood glucose levels:

● After the age of 10 years, the addition of ● A1C levels should be as close to normal ● Critically ill patients: Insulin ther-

a statin is recommended in patients as possible (⬍7%) in an individual pa- apy should be initiated for treat-

who, after MNT and lifestyle changes, tient before conception is attempted. ment of persistent hyperglycemia

have LDL cholesterol ⬎160 mg/dl (4.1 (B) starting at a threshold of no greater

mmol/l) or LDL cholesterol ⬎130 ● Starting at puberty, preconception than 180 mg/dl (10 mmol/l). Once

mg/dl (3.4 mmol/l) and one or more counseling should be incorporated in insulin therapy is started, a glucose

CVD risk factors. (E) the routine diabetes clinic visit for all range of 140 –180 mg/dl (7.8 to 10

● The goal of therapy is an LDL choles- women of child-bearing potential. (C) mmol/l) is recommended for the

terol value ⬍100 mg/dl (2.6 mmol/l). ● Women with diabetes who are contem- majority of critically ill patients. (A)

(E) plating pregnancy should be evaluated These patients require an intrave-

and, if indicated, treated for diabetic nous insulin protocol that has dem-

Retinopathy retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, onstrated efficacy and safety in

and CVD. (E) achieving the desired glucose range

● The first ophthalmologic examination

● Medications used by such women without increasing risk for severe

should be obtained once the child is 10 should be evaluated prior to concep- hypoglycemia. (E)

years of age and has had diabetes for tion, since drugs commonly used to ● Non– critically ill patients: There is

3–5 years. (E) treat diabetes and its complications no clear evidence for specific blood

● After the initial examination, annual

may be contraindicated or not recom- glucose goals. If treated with insu-

routine follow-up is generally recom- mended in pregnancy, including st- lin, the premeal blood glucose tar-

mended. Less frequent examinations atins, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and most get should generally be ⬍140 mg/dl

may be acceptable on the advice of an noninsulin therapies. (E) (7.8 mmol/l) with random blood

eye care professional. (E) glucose ⬍180 mg/dl (10.0 mmol/l),

Older adults provided these targets can be safely

Celiac disease ● Older adults who are functional, cogni- achieved. More stringent targets

● Children with type 1 diabetes should tively intact, and have significant life may be appropriate in stable pa-

be screened for celiac disease by mea- expectancy should receive diabetes care tients with previous tight glycemic

suring tissue transglutaminase or using goals developed for younger control. Less stringent targets may

anti-endomysial antibodies, with adults. (E) be appropriate in those with severe

documentation of normal serum IgA ● Glycemic goals for older adults not comorbidites. (E)

levels, soon after the diagnosis of di- meeting the above criteria may be re- ● Scheduled subcutaneous insulin with

abetes. (E) laxed using individual criteria, but hy- basal, nutritional, and correction.

● Testing should be repeated if growth perglycemia leading to symptoms or Components is the preferred method

failure, failure to gain weight, weight risk of acute hyperglycemic complica- for achieving and maintaining glucose

loss, or gastroenterologic symptoms oc- tions should be avoided in all patients. control in noncritically ill patients. (C)

cur. (E) (E) Using correction dose or “supplemen-

● Consideration should be given to peri- ● Other cardiovascular risk factors tal” insulin to correct premeal hyper-

odic re-screening of asymptomatic in- should be treated in older adults with glycemia in addition to scheduled

dividuals. (E) consideration of the time frame of ben- prandial and basal insulin is recom-

● Children with positive antibodies efit and the individual patient. Treat- mended. (E)

should be referred to a gastroenterolo- ment of hypertension is indicated in ● Glucose monitoring should be initiated

gist for evaluation. (E) virtually all older adults, and lipid and in any patient not known to be diabetic

● Children with confirmed celiac disease aspirin therapy may benefit those with who receives therapy associated with

should have consultation with a dieti- life expectancy at least equal to the time high risk for hyperglycemia, including

tian and placed on a gluten-free diet. frame of primary or secondary preven- high-dose glucocorticoid therapy, initi-

(E) tion trials. (E) ation of enteral or parenteral nutrition,

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S9

Executive Summary

or other medications such as octreotide ● A plan for treating hypoglycemia previous 2–3 months is not available.

or immunosuppressive medications. should be established for each patient. (E)

(B) If hyperglycemia is documented Episodes of hypoglycemia in the hospi- ● Patients with hyperglycemia in the hos-

and persistent, treatment is necessary. tal should be tracked. (E) pital who do not have a diagnosis of

Such patients should be treated to the ● All patients with diabetes admitted to diabetes should have appropriate plans

same glycemic goals as patients with the hospital should have an A1C ob- for follow-up testing and care docu-

known diabetes. (E) tained if the result of testing in the mented at discharge. (E)

S10 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

P O S I T I O N S T A T E M E N T

Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2010

AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

D

iabetes is a chronic illness that re- more detailed information about manage- by the Executive Committee of ADA’s

quires continuing medical care and ment of diabetes, refer to references 1–3. Board of Directors.

ongoing patient self-management The recommendations included are

education and support to prevent acute screening, diagnostic, and therapeutic ac- I. CLASSIFICATION AND

complications and to reduce the risk of tions that are known or believed to favor- DIAGNOSIS

long-term complications. Diabetes care is ably affect health outcomes of patients A. Classification

complex and requires that many issues, with diabetes. A grading system (Table 1), The classification of diabetes includes

beyond glycemic control, be addressed. A developed by the American Diabetes As- four clinical classes:

large body of evidence exists that sup- sociation (ADA) and modeled after exist-

ports a range of interventions to improve ing methods, was used to clarify and ● type 1 diabetes (results from -cell de-

diabetes outcomes. codify the evidence that forms the basis struction, usually leading to absolute

These standards of care are intended for the recommendations. The level of ev- insulin deficiency)

to provide clinicians, patients, research- idence that supports each recommenda- ● type 2 diabetes (results from a progres-

ers, payors, and other interested individ- sive insulin secretory defect on the

tion is listed after each recommendation

uals with the components of diabetes background of insulin resistance)

using the letters A, B, C, or E.

care, general treatment goals, and tools to ● other specific types of diabetes due to

evaluate the quality of care. While indi- These standards of care are revised

annually by the ADA multidisciplinary other causes, e.g., genetic defects in

vidual preferences, comorbidities, and -cell function, genetic defects in insu-

other patient factors may require modifi- Professional Practice Committee, and

new evidence is incorporated. Members lin action, diseases of the exocrine pan-

cation of goals, targets that are desirable creas (such as cystic fibrosis), and drug-

for most patients with diabetes are pro- of the Professional Practice Committee

or chemical-induced diabetes (such as

vided. These standards are not intended and their disclosed conflicts of interest are

in the treatment of AIDS or after organ

to preclude clinical judgment or more ex- listed in the Introduction. Subsequently,

transplantation)

tensive evaluation and management of the as with all position statements, the stan- ● gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

patient by other specialists as needed. For dards of care are reviewed and approved (diabetes diagnosed during pregnancy)

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

Originally approved 1988. Most recent review/revision October 2009. Some patients cannot be clearly classified

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-S011 as having type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Clin-

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle-brachial index; ACCORD, Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes;

ADAG, A1C-Derived Average Glucose Trial; ADVANCE, Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Pre-

ical presentation and disease progression

terax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, vary considerably in both types of diabe-

angiotensin receptor blocker; ACT-NOW, ACTos Now Study for the Prevention of Diabetes; BMI, body tes. Occasionally, patients who otherwise

mass index; CBG, capillary blood glucose; CFRD, cystic fibrosis–related diabetes; CGM, continuous have type 2 diabetes may present with ke-

glucose monitoring; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CCM, chronic care toacidosis. Similarly, patients with type 1

model; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; CSII, continuous

subcutaneous insulin infusion; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hyper- diabetes may have a late onset and slow

tension; DCCT, Diabetes Control and Complications Trial; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; DMMP, diabetes (but relentless) progression despite hav-

medical management plan; DPN, distal symmetric polyneuropathy; DPP, Diabetes Prevention Program; ing features of autoimmune disease. Such

DPS, Diabetes Prevention Study; DREAM, Diabetes Reduction Assessment with Ramipril and Rosiglita- difficulties in diagnosis may occur in chil-

zone Medication; DRS, Diabetic Retinopathy Study; DSME, diabetes self-management education; DSMT,

diabetes self-management training; eAG, estimated average glucose; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration

dren, adolescents, and adults. The true

rate; ECG, electrocardiogram; EDIC, Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications; ERP, diagnosis may become more obvious over

education recognition program; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Reti- time.

nopathy Study; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GDM, gestational

diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HAPO, Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Out- B. Diagnosis of diabetes

comes; ICU, intensive care unit; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; Look

AHEAD, Action for Health in Diabetes; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MNT, medical Recommendations

nutrition therapy; NDEP, National Diabetes Education Program; NGSP, National Glycohemoglobin Stan- For decades, the diagnosis of diabetes has

dardization Program; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test;

PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinop- been based on plasma glucose (PG) crite-

athy; PPG, postprandial plasma glucose; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood ria, either fasting PG (FPG) or 2-h 75-g

glucose; STOP-NIDDM, Study to Prevent Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes; SSI, sliding scale insulin; oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) values.

TZD, thiazolidinedione; UKPDS, U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study; VADT, Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial; In 1997, the first Expert Committee on

XENDOS, XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects.

© 2010 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly

the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabe-

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons. tes Mellitus revised the diagnostic criteria

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. using the observed association between

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S11

Standards of Medical Care

Table 1 —ADA evidence grading system for clinical practice recommendations be used (an updated list of A1C assays and

whether abnormal hemoglobins impact

Level of them is available at www.ngsp.org/prog/

evidence Description index3.html). For conditions with abnor-

mal red cell turnover, such as pregnancy or

A Clear evidence from well-conducted, generalizable, randomized controlled trials that anemias from hemolysis and iron defi-

are adequately powered, including: ciency, the diagnosis of diabetes must use

● Evidence from a well-conducted multicenter trial glucose criteria exclusively.

● Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in the analysis The established glucose criteria for

Compelling nonexperimental evidence, i.e., ⬙all or none⬙ rule developed by Center the diagnosis of diabetes (FPG and 2-h

for Evidence Based Medicine at Oxford PG) remain valid. Patients with severe hy-

Supportive evidence from well-conducted randomized controlled trials that are perglycemia such as those who present

adequately powered, including: with severe classic hyperglycemic symp-

● Evidence from a well-conducted trial at one or more institutions toms or hyperglycemic crisis can continue

● Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in the analysis to be diagnosed when a random (or ca-

B Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies: sual) PG of ⱖ200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) is

● Evidence from a well-conducted prospective cohort study or registry found. It is likely that in such cases the

● Evidence from a well-conducted meta-analysis of cohort studies health care professional would also con-

Supportive evidence from a well-conducted case-control study duct an A1C test as part of the initial as-

C Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studies sessment of the severity of the diabetes

● Evidence from randomized clinical trials with one or more major or three or and that it would be above the diagnostic

more minor methodological flaws that could invalidate the results cut point. However, in rapidly evolving

● Evidence from observational studies with high potential for bias (such as case diabetes such as the development of type

series with comparison to historical controls) 1 in some children, the A1C may not be

● Evidence from case series or case reports significantly elevated despite frank

Conflicting evidence with the weight of evidence supporting the recommendation diabetes.

E Expert consensus or clinical experience Just as there is ⬍100% concordance

between the FPG and 2-h PG tests, there

is not perfect concordance between A1C

glucose levels and presence of retinopa- the A1C test to diagnose diabetes with a and either glucose-based test. Analyses of

thy as the key factor with which to iden- threshold of ⱖ6.5%, and ADA affirms this National Health and Nutrition Examina-

tify threshold FPG and 2-h PG levels. The decision (6). The diagnostic test should tion Survey (NHANES) data indicate that,

committee examined data from three be performed using a method certified by assuming universal screening of the undi-

cross-sectional epidemiologic studies that the National Glycohemoglobin Standard- agnosed, the A1C cut point of ⱖ6.5%

assessed retinopathy with fundus photog- ization Program (NGSP) and standard- identifies one-third fewer cases of undiag-

raphy or direct ophthalmoscopy and ized or traceable to the Diabetes Control nosed diabetes than a fasting glucose cut

measured glycemia as FPG, 2-h PG, and and Complications Trial (DCCT) refer- point of ⱖ126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l) (E.

HbA1c (A1C). The studies demonstrated ence assay. Point-of-care A1C assays are Gregg, personal communication). How-

glycemic levels below which there was lit- not sufficiently accurate at this time to use ever, in practice, a large portion of the

tle prevalent retinopathy and above for diagnostic purposes. diabetic population remains unaware of

which the prevalence of retinopathy in- Epidemiologic datasets show a rela- their condition. Thus, the lower sensitiv-

creased in an apparently linear fashion. tionship between A1C and the risk of ret- ity of A1C at the designated cut point may

The deciles of FPG, 2-h PG, and A1C at inopathy similar to that which has been well be offset by the test’s greater practi-

which retinopathy began to increase were shown for corresponding FPG and 2-h PG cality, and wider application of a more

the same for each measure within each thresholds. The A1C has several advan- convenient test (A1C) may actually in-

population. The analyses helped to in- tages to the FPG, including greater conve- crease the number of diagnoses made.

form a then-new diagnostic cut point of nience, since fasting is not required; As with most diagnostic tests, a test

ⱖ126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l) for FPG and evidence to suggest greater preanalytical result diagnostic of diabetes should be re-

confirmed the long-standing diagnostic stability; and less day-to-day perturba- peated to rule out laboratory error, unless

2-h PG value of ⱖ200 mg/dl (11.1 tions during periods of stress and illness. the diagnosis is clear on clinical grounds,

mmol/l) (4). These advantages must be balanced by such as a patient with classic symptoms of

ADA has not previously recom- greater cost, limited availability of A1C hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis. It

mended the use of A1C for diagnosing testing in certain regions of the develop- is preferable that the same test be repeated

diabetes, in part due to lack of standard- ing world, and incomplete correlation be- for confirmation, since there will be a

ization of the assay. However, A1C assays tween A1C and average glucose in certain greater likelihood of concurrence in this

are now highly standardized, and their re- individuals. In addition, the A1C can be case. For example, if the A1C is 7.0% and

sults can be uniformly applied both tem- misleading in patients with certain forms a repeat result is 6.8%, the diagnosis of

porally and across populations. In a of anemia and hemoglobinopathies. For diabetes is confirmed. However, there are

recent report (5), after an extensive review patients with a hemoglobinopathy but scenarios in which results of two different

of both established and emerging epide- normal red cell turnover, such as sickle tests (e.g., FPG and A1C) are available for

miological evidence, an international ex- cell trait, an A1C assay without interfer- the same patient. In this situation, if the

pert committee recommended the use of ence from abnormal hemoglobins should two different tests are both above the di-

S12 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 care.diabetesjournals.org

Position Statement

Table 2—Criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes costs of false positives (falsely identifying

1. A1C ⱖ6.5%. The test should be performed in a laboratory using a method and then spending intervention resources

that is NGSP certified and standardized to the DCCT assay.* on those who were not going to develop

OR diabetes anyway).

2. FPG ⱖ126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l). Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at Linear regression analyses of nation-

least 8 h.* ally representative U.S. data (NHANES

OR 2005–2006) indicate that among the

3. Two-hour plasma glucose ⱖ200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) during an OGTT. nondiabetic adult population, an FPG of

The test should be performed as described by the World Health 110 mg/dl corresponds to an A1C of

Organization, using a glucose load containing the equivalent of 75 g 5.6%, while an FPG of 100 mg/dl corre-

anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.* sponds to an A1C of 5.4%. Receiver op-

OR erating curve analyses of these data

4. In a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic indicate that an A1C value of 5.7%, com-

crisis, a random plasma glucose ⱖ200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l). pared with other cut points, has the best

combination of sensitivity (39%) and

*In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, criteria 1–3 should be confirmed by repeat testing.

specificity (91%) to identify cases of IFG

(FPG ⱖ100 mg/dl [5.6 mmol/l]) (R.T.

agnostic threshold, the diagnosis of dia- or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (2-h Ackerman, Personal Communication).

betes is confirmed. OGTT values of 140 mg/dl [7.8 mmol/l] Other analyses suggest that an A1C of

On the other hand, if two different to 199 mg/dl [11.0 mmol/l]). 5.7% is associated with diabetes risk sim-

tests are available in an individual and the Individuals with IFG and/or IGT have ilar to that of the high-risk participants in

results are discordant, the test whose re- been referred to as having pre-diabetes, the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)

sult is above the diagnostic cut point indicating the relatively high risk for the (R.T. Ackerman, personal communica-

should be repeated, and the diagnosis is future development of diabetes. IFG and tion). Hence, it is reasonable to consider

made on the basis of the confirmed test. IGT should not be viewed as clinical en- an A1C range of 5.7– 6.4% as identifying

That is, if a patient meets the diabetes cri- tities in their own right but rather risk individuals with high risk for future dia-

terion of the A1C (two results ⱖ6.5%) but factors for diabetes as well as cardiovas- betes and to whom the term pre-diabetes

not the FPG (⬍126 mg/dl or 7.0 mmol/l), cular disease (CVD). IFG and IGT are may be applied (6).

or vice versa, that person should be con- associated with obesity (especially As is the case for individuals found to

sidered to have diabetes. Admittedly, in abdominal or visceral obesity), dyslipide- have IFG and IGT, individuals with an

most circumstance the “nondiabetic” test mia with high triglycerides and/or low A1C of 5.7– 6.4% should be informed of

is likely to be in a range very close to the HDL cholesterol, and hypertension. their increased risk for diabetes as well

threshold that defines diabetes. Structured lifestyle intervention, aimed at as CVD and counseled about effective

Since there is preanalytic and analytic increasing physical activity and produc- strategies to lower their risks (see IV. PRE-

variability of all the tests, it is also possible ing 5–10% loss of body weight, and cer- VENTION/DELAY OF TYPE 2 DIABETES).

that when a test whose result was above tain pharmacological agents have been As with glucose measurements, the contin-

the diagnostic threshold is repeated, the demonstrated to prevent or delay the de- uum of risk is curvilinear, so that as A1C

second value will be below the diagnostic velopment of diabetes in people with IGT rises, the risk of diabetes rises dispropor-

cut point. This is least likely for A1C, (see Table 7). It should be noted that the tionately. Accordingly, interventions

somewhat more likely for FPG, and most 2003 ADA Expert Committee report re- should be most intensive and follow-up

likely for the 2-h PG. Barring a laboratory duced the lower FPG cut point to define should be particularly vigilant for those

error, such patients are likely to have test IFG from 110 mg/dl (6.1 mmol/l) to 100 with an A1C ⬎6.0%, who should be con-

results near the margins of the threshold mg/dl (5.6 mmol/l), in part to make the sidered to be at very high risk. However,

for a diagnosis. The healthcare profes- prevalence of IFG more similar to that of just as an individual with a fasting glucose of

sional might opt to follow the patient IGT. However, the World Health Organi- 98 mg/dl (5.4 mmol/l) may not be at negli-

closely and repeat the testing in 3– 6 zation (WHO) and many other diabetes gible risk for diabetes, individuals with an

months. organizations did not adopt this change. A1C ⬍5.7% may still be at risk, depending

The current diagnostic criteria for di- As the A1C becomes increasingly on the level of A1C and presence of other

abetes are summarized in Table 2. used to diagnose diabetes in individuals risk factors, such as obesity and family

with risk factors, it will also identify those history.

C. Categories of increased risk for at high risk for developing diabetes in the

diabetes future. As was the case with the glucose Table 3—Categories of increased risk for

In 1997 and 2003, The Expert Committee measures, defining a lower limit of an in- diabetes*

on the Diagnosis and Classification of Di- termediate category of A1C is somewhat FPG 100–125 mg/dl (5.6–6.9 mmol/l)

abetes Mellitus (4,7) recognized an inter- arbitrary, since risk of diabetes with any 关IFG兴

mediate group of individuals whose measure or surrogate of glycemia is a con- 2-h PG on the 75-g OGTT 140–199 mg/dl

glucose levels, although not meeting cri- tinuum extending well into the normal (7.8–11.0 mmol/l) 关IGT兴

teria for diabetes, are nevertheless too ranges. To maximize equity and efficiency A1C 5.7–6.4%

high to be considered normal. This group of preventive interventions, such an A1C

*For all three tests, risk is continuous, extending

was defined as having impaired fasting cut point, should balance the costs of false below the lower limit of the range and becoming

glucose (IFG) (FPG levels of 100 mg/dl negatives (failing to identify those who are disproportionately greater at higher ends of the

[5.6 mmol/l] to 125 mg/dl [6.9 mmol/l]) going to develop diabetes) against the range.

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, SUPPLEMENT 1, JANUARY 2010 S13

Standards of Medical Care

Table 4—Criteria for testing for diabetes in asymptomatic adult individuals Recommendations for testing for dia-

1. Testing should be considered in all adults who are overweight (BMI ⱖ25 kg/m *) and

2 betes in asymptomatic undiagnosed

have additional risk factors: adults are listed in Table 4. Testing should

● physical inactivity

be considered in adults of any age with

● first-degree relative with diabetes

BMI ⱖ25 kg/m2 and one or more risk fac-

● members of a high-risk ethnic population (e.g., African American, Latino, Native

tors for diabetes. Because age is a major

American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

risk factor for diabetes, testing of those

● women who delivered a baby weighing ⬎9 lb or were diagnosed with GDM

without other risk factors should begin no

● hypertension (ⱖ140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension)

later than at age 45 years.

● HDL cholesterol level ⬍35 mg/dl (0.90 mmol/l) and/or a triglyceride level ⬎250

Either A1C, FPG, or 2-h OGTT is ap-

mg/dl (2.82 mmol/l)

propriate for testing. The 2-h OGTT identi-

● women with polycystic ovary syndrome

fies people with either IFG or IGT and thus

● A1C ⱖ5.7%, IGT, or IFG on previous testing

more people at increased risk for the devel-

● other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., severe obesity,

opment of diabetes and CVD. It should be

acanthosis nigricans)

noted that the two tests do not necessarily

● history of CVD

detect the same individuals (10). The effi-

2. In the absence of the above criteria, testing diabetes should begin at age 45 years

cacy of interventions for primary preven-

3. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at least at 3-year intervals, with tion of type 2 diabetes (11–17) has

consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk primarily been demonstrated among indi-

status. viduals with IGT, but not for individuals

with IFG (who do not also have IGT) or

*At-risk BMI may be lower in some ethnic groups.

those with specific A1C levels.

The appropriate interval between

Table 3 summarizes the categories of who the provider tests because of high tests is not known (18). The rationale for