Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Librarian's Perspective On Vaccinations

Caricato da

VTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Librarian's Perspective On Vaccinations

Caricato da

VCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research reports: Keselman et al.

can help librarians provide resources to address

health controversies.

INTRODUCTION

The United States is seeing a growing number of

parents refusing or delaying recommended childhood

vaccinations, as well as a rise in vaccine-preventable

diseases [1]. Some of these parents—intentional non-

adherents—avoid vaccination because of concerns

about vaccines’ safety and a perceived low suscepti-

bility to vaccine-preventable diseases [2, 3]. While their

beliefs and attitudes may be strong, most of these

parents appear to be earnestly open to both sides of the

controversy and express the desire for unbiased

information [4]. Other parents—unintentional non-

adherents—slip off the vaccination schedule because

of a variety of logistical and socio-demographic factors.

While these parents are generally aware that childhood

vaccination is important, their lack of specific knowl-

edge contributes to low vaccination rates [5]. Both

categories of parents could benefit from skilled help in

navigating vaccination information and understanding

its sources.

While a need for health information is one reason

that the public visits public libraries [6], little is

known about public librarians’ knowledge about

childhood vaccination and vaccination information

Library workers’ personal beliefs about resources, as well as their practices in guiding patrons

childhood vaccination and vaccination who are concerned about vaccination. In helping

information provision* members of the general public navigate controversial

health information, public librarians likely struggle

Alla Keselman, PhD; Catherine Arnott Smith, PhD; with the same tension between neutrality and

Savreen Hundal, MA advocacy that health sciences librarians experience

when dealing with the information needs of patients

See end of article for authors’ affiliations. and their families. On the one hand, the principle of

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.012 collection neutrality, expressed in the Library Bill of

Rights [7], maintains that particular viewpoints

should not be privileged over others and that a broad

This is a report on the impact of library workers’ scope of views is required. On the other hand, the

personal beliefs on provision of vaccination neutrality position has historically been a contested

information. Nine public librarians were interviewed position, with some professional voices maintaining

about a hypothetical scenario involving a patron who that there are times when librarians should be

is concerned about possible vaccination-autism advocates [8]. This tension in vaccination information

connections. The analysis employed thematic provision is the subject of this research report.

coding. Results suggested that while most partic- This paper presents an in-depth qualitative study of

ipants supported childhood vaccination, tension nine library workers’ beliefs and attitudes about

between their personal views and neutrality childhood vaccination, their knowledge of health

impacted their ability to conduct the interaction. The information resources, and their response to a hypo-

neutrality stance, though consonant with professional thetical reference scenario involving a young mother

guidelines, curtails librarians’ ability to provide who is concerned about a possible connection between

accurate health information. Outreach and commu- childhood vaccination and autism. In particular, the

nication between public and health sciences libraries authors were interested in exploring the potential

impact of personal beliefs, as well as the role of

mitigating factors such as professional standards and

knowledge about resources, on provision of informa-

* This work was supported in part by the intramural research tion about vaccination. The impetus for the study was

program of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Flaherty and Luther’s investigation of public librari-

Institutes of Health, and by NLM contract HHSN2762008000360P ans’ responses to pseudo-patrons’ questions about the

with the Center for Public Service Communications. connection between autism and vaccination [9].

J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014 205

Research reports: Keselman et al.

METHODS & ‘‘Without vaccinations, a child may get a disease.’’

& ‘‘Without vaccinations, a child can cause other

Participants children and adults to get the disease.’’

& ‘‘Vaccines are necessary.’’

The nine participants in this study (five white, three

& ‘‘Vaccines are safe.’’

African American, one Hispanic; seven women,

& ‘‘Serious side effects can occur with vaccination.’’

two men) worked in eight public libraries in four

library systems: the District of Columbia, Montgom- Six-point-scale response options ranged from ‘‘Strongly

ery County and Prince George’s County (Maryland), disagree’’ (1) to ‘‘Strongly agree’’ (6).

and Fairfax County (Virginia). Eight held master

of library science (MLS) degrees; one was a para- Analysis

professional. The four systems were chosen to

All interviews were audio-recorded, and transcribed

represent a diversity of public library branches in

and coded using NVivo 10 (QSR; Sydney, Australia).

the area. The general region was chosen because of

The coding scheme was adapted from Smith [12] and

its proximity to the institution of one of the principal

modified through pilot coding and resolving of

investigators.

disagreement by discussion. Each protocol was coded

by two authors.

Recruitment

RESULTS

Administrators at the four library systems collectively

suggested eight libraries as representative. The Summary of personal positions on vaccination

eight library directors were asked to identify library

workers with considerable reference responsibilities. Review of the responses to the questionnaire reveals

that none of the participants were opposed to

Protocol{ vaccination. All agreed or strongly agreed that

vaccines are necessary; no one disagreed that vaccines

The library workers completed a short questionnaire are safe. Yet, nuanced analysis of response patterns

and participated in one-on-one, semi-structured in- suggested a different level of internal consistency of

terviews led by an undergraduate student. The participants’ beliefs. Three patterns of response

interviews included questions about common con- emerged. We identify our participants as Staunch,

sumer health information requests, librarians’ collec- Concerned, and Tentative Believers (Figure 1).

tions and preferred health information sources, and

their beliefs about the role of public libraries in Three positions

addressing consumer health information needs. It also

presented two scenarios involving hypothetical pa- Staunch Believers. Participants 5, 8, and 9 were the

trons’ queries: one about Medicare Part D and the Staunch Believers: They not only saw vaccines as

other about childhood vaccination and autism. Gen- ‘‘necessary for the individual, but also for public

eral results and the complete interview guide can be health’’ (Participant 5), but also disagreed or strongly

found elsewhere [10]. The section of the interview disagreed with the statement that ‘‘serious side effects

pertaining to addressing a vaccination query provid- can occur with vaccination.’’ This disagreement did not

ed the basis for this study: mean that they saw the likelihood of side effects as the

& We are interested in your own views about one absolute statistical zero; rather, they viewed risks as

kind of health information, which is about vaccina- minimal and benefits as highly exceeding the risks. For

tion. It would be very helpful if you could fill out the example, Participant 5 stated, ‘‘I do understand that

following short questionnaire. (See the questionnaire every once in a while there are some side effects to some

below.) Could you please talk a bit about each of your vaccines, [but] the side effects are very moderate…, so

answers. it’s better than getting whatever the ailment is.’’

& Imagine that a patron, a young mother, approached These participants viewed eradication of vaccine-

you because she was concerned that vaccinations may preventable diseases as a remarkable human achieve-

cause autism. She is looking for information. What ment and denial of vaccination as voluntarily giving

resources would you suggest to her and why? up a major public health victory. For example, on

& We’d like to hear about what you think are the noting that ‘‘some diseases that we thought were

challenges of this kind of question. stamped back are coming back,’’ Participant 8

The questionnaire, modified from previous studies continued, ‘‘I think that it would be a shame to slip

on attitudes toward vaccination [3, 11], asked partic- back to those days where we know how to prevent

ipants to rate their agreement or disagreement with something and we are not.’’

the following statements:

Concerned Believers. Participants 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6

agreed (Participant 6) or strongly agreed (the rest) that

{ The protocol received institutional review board exemption from vaccines are necessary. They also agreed (Participant

the National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research 3) or strongly agreed that without vaccination, a child

(OHSR). might get a disease and cause others to get it (the rest).

206 J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014

Research reports: Keselman et al.

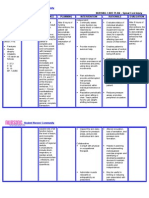

Figure 1

Average strength of agreement or disagreement with survey questions for Staunch Believers (SB), Concerned Believers (CB), and the Tentative

Believer (TB)*{

* Values along the x-axes represent the 5 questions of the questionnaire.

{ The bars represent mean strengths of agreement or disagreement with the 5 questions of the questionnaire for each of the 3 participants’ positions. Ranges of

standard deviations from the mean were the following: SB (participants 5, 8, 9): 0–0.58; CB (participants 1, 2, 3, 4, 6): 0.45–0.89. As there was only 1 TB (participant 7),

no standard deviation can be reported.

However, four of the five ‘‘Slightly agreed’’ that believe in vaccinations and I think that they’re

serious side effects can occur with vaccination. One important; if I had a child I would vaccinate them.’’

(Participant 6) strongly agreed with this view. She continued by saying, ‘‘However there are side

Like Staunch Believers, Concerned Believers see effects, or there could be side effects…So I understand

many individual and societal values in vaccination. why some people are hesitant.’’

This is exemplified by Participant 4’s statement, ‘‘I

think that [vaccines] are for the good of the child and Tentative Believer. Of all the participants in the study,

of society at large.’’ Where Concerned Believers Participant 7 had the most tentative attitudes toward

differed from Staunch Believers was in their percep- vaccination. It appears that his tentativeness stemmed

tion of vaccination-related risks, which they described not so much from concerns about vaccine safety, as from

in more specific, palpable terms. For example, when beliefs in natural immunity and individual differences

explaining her opinion about whether vaccines were in immune response that diminish the positive value of

safe, Participant 1 stated, ‘‘Generally safe.’’ She then vaccination. In explaining why he ‘‘Slightly agreed’’ that

continued, ‘‘I won’t say that all of them are safe…You without vaccinations a child might get a disease, this

need to take into consideration allergies and the participant said, ‘‘You are not necessarily always going

health problems of the individual and this kind of to get that disease because it depends…[For example], I

thing. Okay, see, problem with this is that you can’t have a strong resistance to malaria. I could be in a

say that it’s absolutely safe.’’ malaria area and I won’t get it. But then somebody else

Despite their concerns about vaccine safety, these might not have the same resistance I have and they’ll get

participants weighted the risk/benefit ratio in favor of malaria.’’ This participant similarly invoked individual

vaccination. For example, Participant 3 stated, ‘‘I differences in immune response when explaining his

J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014 207

Research reports: Keselman et al.

slight disagreement with the statement that serious side childhood vaccination, they refrained from letting

effects can occur with vaccination. Although this their views guide their resource selection toward

participant viewed susceptibility to vaccine-predictable advocacy. For example, Participant 5 would take the

diseases and vaccine reaction as highly individualized, concerned mother to two types of library books: the

he nevertheless agreed with the statement that vaccines ‘‘health section about vaccinations’’ and ‘‘books about

are necessary. vaccines as a social issue.’’ His response positioned a

vaccination decision as a social, rather than a scientific

Distinction between personal views and debate.

professional role While participants tended to refrain from express-

ing their personal opinions, they were strong believ-

In discussing their role in helping the hypothetical ers in providing quality information. ‘‘Quality,’’ for

patron, participants often mentioned remaining neu- these respondents, meant that a resource was ‘‘reli-

tral and abstaining from expressing their personal able’’ and free of bias, particularly commercial bias.

views as essential to their mission. The value of This clearly conflicted with their desire to present the

neutrality was upheld by participants regardless of patron with ‘‘both sides’’ of the debate. For example,

their personal beliefs about vaccination. For example, Participant 5 stated at one point, ‘‘I will give them all

Participant 2, a concerned believer, eloquently stated, the books, I will put both [sides] out there,’’ but at

‘‘as a professional librarian, it’s not my job to tell another point in the interview, maintained, ‘‘I would

people whether they should vaccinate their children be pretty reluctant to use a private website, like a drug

or not. And I wouldn’t give my opinion about that.’’ company.’’ Participant 2 was equally ambivalent,

making statements that advocated neutrality, while

Recommended resources also favoring ‘‘primarily government,’’ ‘‘unbiased’’

sources.

Participants had been presented with a hypothetical

One attempt to reconcile these positions involved

patron scenario in which a young mother approached

presenting a broad range of information sources,

them because she was concerned that vaccinations

while supporting patrons’ evaluations of that infor-

might cause autism. A hypothetical patron described by

a third party in an interview setting away from the mation. Several respondents spoke to this directly. For

reference desk is very different from a real patron example, Participant 1 stated: ‘‘We have several

standing at the desk asking for information. For that books…one of them…tries to look at the pros and

reason, the interviewees had difficulty making specific cons of vaccination. It tries to be relatively neutral…it

suggestions. Two people indicated that they would use won’t push one side or the other.’’ Soon after, this

‘‘library-subscribed,’’ ‘‘consumer health,’’ or ‘‘magazine participant suggested that the young mother could

databases’’ (Participants 8 and 9) or ‘‘books on autism’’ visit ‘‘websites like PubMed and MedlinePlus and be

(Participant 9); another referred to a ‘‘relatively neutral’’ taken to sources that specialize in autism’’ to compare

book in her library’s collection covering vaccination ‘‘the probability of getting [vaccine preventable]

‘‘pros and cons.’’ However, most subjects could name illness or problem if you do not get the vaccine’’ with

specific electronic resources. Participants from all three ‘‘the likelihood [that]…vaccines can cause autism.’’

philosophical positions mentioned resources from the

Department of Health and Human Services, National Tentative Believer. In discussing his strategies, Par-

Institutes of Health (NIH), and National Library of ticipant 7 established himself as a strong proponent of

Medicine (NLM), specifically, PubMed and Medline- neutrality. He said (as previously quoted), ‘‘I like to

Plus. One of the cautious supporters (Participant 2) also give all different viewpoints to the person to make sure

mentioned an ‘‘autism awareness organization web- that they see all different sides of the arguments.’’ Also,

site.’’ Finally, the Tentative Believer mentioned WebMD his list of suggested resources spanned a variety of

and Mercola.com, which is one of the most ‘‘heavily information sources and positions on vaccination: ‘‘I

trafficked’’ alternative medicine sites [13] officially would give her a couple of different sites to see the

warned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) various viewpoints…like Dr. Mercola, a traditional site

[14]. like WebMD, and NIH or NLM site concerning any

studies from PubMed…concerning vaccination and

Justification of source selection autism. And then I would show her copies of any

books we have related to that.’’ This participant did not

When asked why they would turn to particular discuss criteria for ‘‘quality’’ information and did not

resources, participants attempted to adhere to two explicitly exclude any types of information sources.

not easily compatible positions: dedication to neutral-

ity, requiring them to present a broad spectrum of DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

opinions, and dedication to information quality,

represented by sources with traits of authoritative- The objective of this report was to conduct a study

ness, reliability, and a solid base of evidence. into library workers’ personal beliefs about childhood

vaccination, their knowledge of health information

Staunch Believers and Cautious Believers. While resources, and the impact of personal beliefs on

these participants believed in the importance of vaccination information provision.

208 J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014

Research reports: Keselman et al.

The study had some limitations that need to be con- care providers. This controversial topic can be

sidered in interpreting the findings. The small sample, addressed through the professional channels, such

necessitated by the interview methodology befitting the as outreach programs, through which information

research question, did not allow the authors to gener- professionals of different types communicate with

alize our findings about our participants’ mostly and educate each other. Public library workers, after

strongly pro-vaccination stances to the general popula- all, are consumers, too, and are likely to have

tion of public librarians. The study involved a hypo- questions about vaccines themselves.

thetical scenario, which prevented participants from

drawing on the richness of verbal and nonverbal cues REFERENCES

inherent in a real reference interaction. In addition, this

was not a study of reference interviews, which meant 1. Hampton T. Outbreaks spur measles vaccine studies.

that participants’ strategies for completely meeting real JAMA. 2011 Dec 14;306(22):2440–2.

patrons’ information needs could not be explored in real 2. Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have

depth. These limitations might well explain the lack of received no vaccines: who are they and where do they live?

Pediatrics. 2004 Jul;114(1):187–95.

specificity in recommended resources.

3. Kennedy AM, Brown CJ, Gust DA. Vaccine beliefs of

With regard to this report, the most salient findings parents who oppose compulsory vaccination. Pub Health

are two areas of professional tension. The first is Rep. 2005 May–Jun;120(3):252–8.

between participants’ personal views (largely sup- 4. Gullion JS, Henry L, Gullion G. Deciding to opt out of

portive of vaccination) and the view that they feel childhood vaccination mandates. Pub Health Nurs. 2008

they can bring to the reference transaction, that is, no Sep–Oct;25(5):401–8.

views. The second is between neutrality (the above- 5. Baker LM, Wilson FL, Nordstrom CK, Legwand C.

mentioned view of bringing no views) and commit- Mothers’ knowledge and information needs relating to

ment to information quality. While the neutrality childhood immunizations. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2007

stance is completely consonant with professional Jan–Jun;30(1–2):39–53.

6. Lee R, Estabrook L, Witt E. Information searches that

practice guidelines, avoidance of the information

solve problems [Internet]. Pew Internet & American Life

quality problem has the potential to limit public Project; 30 Dec 2007 [cited 30 Jul 2013]. ,http://www

librarians’ ability to promote and support public .pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Information-Searches-That

health. Are librarians simply conduits to sources -Solve-Problems.aspx..

containing answers to questions, or are they socially 7. American Library Association. Library bill of rights

responsible agents in the transaction? The answer to [Internet]. The Association; 23 Jan 1980 [cited 19 Aug 2013].

this question affects not only collection development ,http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill/..

and maintenance—the arena in which ‘‘neutrality’’ is 8. Highby W. The ethics of academic collection develop-

traditionally explored—but also reference services, ment in a politically contentious era. Lib Coll Acq Tech Serv.

since library workers turn to their institution’s 2005;28(4):465–72.

collections to answer questions. This professional 9. Flaherty MG, Luther ME. A pilot study of health

information resource use in rural public libraries in Upstate

dilemma is an old one. It has been articulated and New York. Pub Lib Q. 2011 Jun;30:117–31.

argued about since the dawn of the public library 10. Smith CA, Hundal SM, Keselman A. Knowledge gaps

‘‘medical department’’ in the 1880s [15]. It was refined among public librarians seeking vaccination information: a

in the early years of the AIDS epidemic [16], in the qualitative study. J Cons Health Internet. Forthcoming 2014.

context of the library’s obligation to provide informa- 11. Kennedy A, Basket M, Sheedy K. Vaccine attitudes,

tion on condoms to teenagers. It was also recently concerns, and information sources reported by parents of

underlined in two other health-related contexts. young children: results from the 2009 HealthStyles survey.

Malizia and Vargas wrote about the support that Pediatrics. 2011 May;127(suppl 1):S92–9.

public libraries and library staff provide in the event 12. Smith CA. ‘‘The easier-to-use version’’: public librarian

of natural disasters as information hubs and as awareness of consumer health resources from the National

Library of Medicine. J Cons Health Internet. 2011;15(2):

shelters [17]. Public libraries have also been identified

149–63.

as information resources about enrollment for cover- 13. Smith B. Dr. Mercola: visionary or quack? Chicago

age through the Patient Protection and Affordable Magazine [Internet]. 12 Feb 2012 [cited 30 Jul 2013]. ,http://

Care Act [18]. www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/February-2012/

Our small study also has implications for health Dr-Joseph-Mercola-Visionary-or-Quack/..

sciences librarians who work with consumers and 14. US Food and Drug Administration. Inspections, com-

patients on the particular issue of vaccination. First, it pliance, enforcement, and criminal investigations [Internet].

is clear that the public library can be a source of useful The Administration; 22 Mar 2011 [cited 30 Jul 2013]. ,http://

health information. The public library workers we www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/

interviewed would be able to direct their real-life 2011/ucm250701.htm..

15. Spivak CD. Medical departments in public libraries.

patrons to many reliable, authoritative consumer

Med Lib. 1902;5(4):17–24.

health electronic and print resources. Second, our 16. Anderson AJ. Captain Condom. Lib J. 1990:115.

scenario centered on a controversial topic: autism and 17. Malizia M, Vargas K. Connecting public libraries with

a purported connection to childhood vaccination. This community emergency responders. Pub Lib. 2012;51(3):32–7.

social issue is a public health concern with implica- 18. Institute of Museum and Library Services. IMLS and

tions for any clinic: it directly affects families’ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to partner with

potential communication with their children’s health libraries [Internet]. The Institute; 1 Jul 2013 [cited 18 Nov 2013].

J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014 209

Research reports: MacDonald et al.

,http://www.imls.gov/imls_and_centers_for_medicare_and_

medicaid_services_to_partner_with_libraries.aspx..

AUTHORS’ AFFILIATIONS

Alla Keselman, PhD, keselmana@mail.nih.gov, Se-

nior Social Science Analyst, Division of Specialized

Information Services, US National Library of Medi-

cine, 6707 Democracy Boulevard, Suite 510, Bethesda,

MD 20892-5467; Catherine Arnott Smith, PhD,

casmith24@wisc.edu, Associate Professor, School of

Library and Information Studies, University of Wis-

consin–Madison, Room 4217, Helen C. White Hall, 600

North Park Street, Madison, WI 53706; Savreen

Hundal, MA, savreenhundal@gmail.com, Contractor,

Center for Public Service Communications, 10388

Bayside Drive, Claiborne, MD 21624

Received September 2013; accepted January 2014

210 J Med Lib Assoc 102(3) July 2014

Copyright of Journal of the Medical Library Association is the property of Medical Library

Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- 2020 Women's Decision Re Mode of BirthDocumento11 pagine2020 Women's Decision Re Mode of BirthVNessuna valutazione finora

- Risks Factors & VaccinationDocumento16 pagineRisks Factors & VaccinationVNessuna valutazione finora

- Stds and Pregnancy: Protect Yourself + Protect Your PartnerDocumento4 pagineStds and Pregnancy: Protect Yourself + Protect Your PartnerVNessuna valutazione finora

- Stds and Pregnancy: Protect Yourself + Protect Your PartnerDocumento4 pagineStds and Pregnancy: Protect Yourself + Protect Your PartnerVNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Perceptions of VaccinationDocumento24 pagineCommunity Perceptions of VaccinationVNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics & Childhood VaccinationDocumento7 pagineEthics & Childhood VaccinationVNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatitis B Vaccination PDFDocumento13 pagineHepatitis B Vaccination PDFVNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Series Screenwriter Portfolio by SlidesgoDocumento24 pagineSeries Screenwriter Portfolio by SlidesgoYeddah Gwyneth TiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatic Disease in PregnancyDocumento37 pagineHepatic Disease in PregnancyElisha Joshi100% (1)

- Invitae - TRF938 Invitae FVT VUS OrderFormDocumento2 pagineInvitae - TRF938 Invitae FVT VUS OrderFormMs.BluMoon SageNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Diabetic Foot ComplicaDocumento25 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Diabetic Foot Complicafebyan yohanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Transfer of Medicines SOPDocumento3 pagineTransfer of Medicines SOPPROBLEMSOLVERNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 11 StsDocumento3 pagineChapter 11 StsCute kittyNessuna valutazione finora

- Flap Approaches in Plastic Periodontal and Implant Surgery: Critical Elements in Design and ExecutionDocumento15 pagineFlap Approaches in Plastic Periodontal and Implant Surgery: Critical Elements in Design and Executionxiaoxin zhangNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantage and DisadvantageDocumento5 pagineAdvantage and Disadvantageحسين يوسفNessuna valutazione finora

- McKenzie Method for Back Pain ReliefDocumento74 pagineMcKenzie Method for Back Pain Relieframsvenkat67% (3)

- Progyluton-26 1DDocumento16 pagineProgyluton-26 1DUsma aliNessuna valutazione finora

- ENdo FellowshipDocumento2 pagineENdo FellowshipAli FaridiNessuna valutazione finora

- Secondary Survey for Trauma PatientsDocumento18 pagineSecondary Survey for Trauma PatientsJohn BrittoNessuna valutazione finora

- 852-Article Text-1782-1-10-20221103Documento11 pagine852-Article Text-1782-1-10-20221103ritaNessuna valutazione finora

- 113 1 358 1 10 20190708 PDFDocumento7 pagine113 1 358 1 10 20190708 PDFGalih Miftah SgkNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Medicine Board Review - Pass Your ABFM Exam - CMEDocumento6 pagineFamily Medicine Board Review - Pass Your ABFM Exam - CMEa jNessuna valutazione finora

- NURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsDocumento4 pagineNURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsEmma WatsonNessuna valutazione finora

- First Aid NewDocumento47 pagineFirst Aid Newchristopher100% (1)

- Basic NutritionDocumento50 pagineBasic NutritionKate Angelique RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Spay & Neuter Clinic Price ListDocumento1 paginaSpay & Neuter Clinic Price ListLorinda MckinsterNessuna valutazione finora

- ICH E2E GuidelineDocumento20 pagineICH E2E Guidelinetito1628Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Article: Plant Leaves Extract Irrigation On Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot UlcersDocumento9 pagineResearch Article: Plant Leaves Extract Irrigation On Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot UlcersHyacinth A RotaNessuna valutazione finora

- BeWell Assignment 2 W22Documento8 pagineBeWell Assignment 2 W22Christian SNNessuna valutazione finora

- EO094 COVIDRecommendationsDocumento4 pagineEO094 COVIDRecommendationsTMJ4 News50% (2)

- Student's Handbook 2014Documento52 pagineStudent's Handbook 2014Ahmed MawahibNessuna valutazione finora

- NCPDocumento2 pagineNCPsphinx809100% (2)

- Medication Competency Questions For NursesDocumento13 pagineMedication Competency Questions For NursesAlex AndrewNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study DM 2 PWDTDocumento8 pagineCase Study DM 2 PWDTsantis_8Nessuna valutazione finora

- CASE STUDY of HCDocumento3 pagineCASE STUDY of HCAziil LiizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cleveland Doctor Disciplined by Medical BoardDocumento6 pagineCleveland Doctor Disciplined by Medical BoarddocinformerNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Activity Report (Or Terminal Report)Documento14 paginePost Activity Report (Or Terminal Report)luningning0007Nessuna valutazione finora