Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Rosen and Wolff 1a and 1b

Caricato da

creamyfrappe0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

8 visualizzazioni21 pagineReadings

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoReadings

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

8 visualizzazioni21 pagineRosen and Wolff 1a and 1b

Caricato da

creamyfrappeReadings

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 21

La. The Natural State of Mankind

=

ym their beginnings. Fi

ther must unite asa pat: For example,

not from choice; rather, as in the ather animals too

rand slave benef from the same thing

‘sy nature that a distinction has been made between female and slave.

sure ptoduces nothing skimpily like the Delphic knife that smiths make),

Dut one thing for one purpose; for every tool will be made best if it subserves

ks but one. Non-Greeks, however, assign to fernale and slave the

same status. This is because they do not have that which naturally rules:theiras-

tion comes tobe thatof amale lave anda female slave. Hence, asthe poets

oper that Greeks should rule non-Greeks’, on the assumption that

frst of all ahouse and a wife and an ox

to draw the plough,’ (The oxis the poor man's slave) Sothe association formed

comature for the satisfaction of the purposes of every day is« house-

bold, the members of which Charondas calls bread fellows’, and Epimenides

the Cretan ‘stable-companions

from several households, for the satisfaction of other

village. The village seems co be by nature inthe highest

asa colony of a household—children and grandchildren, whom some

were at frst ruled by kings (as are

tered and

gods too are said by

be governed by 2 king—namely because men the were

ruled by kings and some are so still. Men model the gods’ forms on

and similarly their way of life too,

reason the,

‘THOMAS HOBBES.

no states either a wretch or supet

‘man; h ike the man condemned by Homer as having. thethood

for he iat once such by nature and keen to go to wer, being

isolated lke a piece ina game

(rom Pete ot

£4 Tho Misory of the Natural Condition of Mankind

quicker mind than another, yet when allisreckoned together, the difference be

tween man, and man, is not so considerable, as that one man

to which another may

selves, they approve. For such isthe nature of men, thathowsoeverthey may ac:

knowledge many others tobe more

yet they will hardly bel

or more eloquent, or more learned:

so wise as themselves; for they see

there be mat

1 HUMAN NATURE

their own witathand, and other men's ata distance. Butthis proveth ratherthat

‘men are in that point equal, than unequal. For there is nor ordinarily a greater

sign of the equal distribution of any thing, than that every man is contented

with his share

From this equality of ability, sriseth equality of hope inthe attaining of opr

As tes Cat Crone Wee sae eg ll neti

cannot both enjoy. they become enemies; and in the way to their end,

ich s principally their own conservation, and sometimes their delectation

only)endeavourto destroy, or subdue one another. And from hen

at where an invader hath no more to feat, than another man’s single

hers may prob

10 dispostess, and de

butalso of his life or liber: And

the invader again isin th ike danger of another,

A And from this difidence of one another, there it no way for any man tose

cure himself so reasonable, as anticipation; that, by fore, or wiles, to master

the perspns of all men he can, so long, lhe see no other power great enough

to endange him: and this iso more than his own conservation requireth, and

is generally allowed. Also because there be some, that taking pleasure in con

templating their own power inthe acts of conquest, which they pursue farther

than theirsecurty requires; if others, that otherwise would be glad tobe at ease

‘within modestbounds shouldnotby invasion inerease their power, they would

not beable, longime, by standing only ontheirdefence, to subsist And by com

sequence, such augmentation of dominion over men, being necessary to a

‘man’s conservation, itought to be allowed him.

‘Again, men have no pleasure, (but on the contrary a great deal of grief) in

keeping company, where there so povier able to over.awe them all. For every

asiar ashe dares {which amongst them that have no coramon power

quiet, is far enough ro make them destroy each other to.extorea

seater value ftom his contemners, by dimage; and ftom others, by the ex

ample

So thai the nature of man, we find three principal causes of quarrel Fits,

‘competition; secondly difidence; tied, glory.

“The firs, maketh men invade for gin; the second, fr safety: andthe third,

for reputation. The first use violence, 19 make themselves masters of other

smen'spersons, wives, chilren, and cate the second, to defend them; the third,

a smile, diferent opinion, and any other sgn of under

jon in their kindred, their

power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war;

THOMAS HORBES 5

and such a war, asis of every man, against every man, For wan, consisteth notin

bane only, orthe act of fighting: but in a trac of time, where

tend by battle is suficiently known: and therefore the not

considered in the nature of war;asit isin the nature of weather. Fo

ture of foul weather, lieth not

ereto of many days together:

fighting; but n the known dispos ro, duringall the time there is no as

the contrary. All other time is react.

‘Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of wat, where every man is

enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live

without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention

shall furnish chem withal. In such condition, there is no place for industry; be

cause the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earch;

‘no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no

commodious building; no instruments of moving, and zemovingsuch things as

require much force; no knowledge of the face of the eafth;no account of time:

‘no arts;no letters; no society; and which is worst ofall

ger of violent death; andthe life of man, s

‘may seem strange to some man, that has weighed these

that nature should thus disso der men apt to invade, and destroy

ing to this inference, made from

sccks to go well accompanied; when going to sleep, he locks

even in his house he locks his chests; nd this when he knows there be laws, and

abject when ees med of fellow ctzens here

leckisdoonsand fitch aera hen oth cts Dees

Denotes mich case maningby histo dosy my wor Bat

sete of sacs asain The ese and eke pasonso mo

arinthemelesno sn Noor ce the ction tha proceed fom hosp

Sons il hey now sth este which i laws be me eyo

zotknos no cana be made il hey hve ged pen the pon a

dalmatee

Itmypeadventure be though there was eer sch time, nor ond

of ware hand beets never gnealy o,oe athe wor

arc many plas, where te ine ono Forte sage people many Paes

of Amerie ecepethe goverment al niente concord wherea e

pendeth on natal lst eno goverment at al andi at isan it

brash mines td before Fowsoee mye peed wha net

ofifthee would, where thee mere nocommonpowerte eb the mun

ber of, which men tha ave former ved unde a peel government

tet degenerate int, ina cll wae,

iq HUMAN NATURE

Bur though there had never been any time, wherein particular men wereina

condition of war one against another: yet inal times, kings, and persons of sov-

authority, because oftheir independency. are in continual ealousies, and

he state and posture of gladiators; having their weapons pointing, and their

eyes fixed on one another; thats, theic forts, garrisons, and guns upon the froa-

sof their kingdoms; and continual spies upon their neighbours; which isa

posture of war But because they uphold thereby, the industry of their subjects;

‘there does not follow from it, that misery, which accompaniesthe liberty of par

ticular men,

‘To this war of every man against every man, this also is consequent; that

nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and

Ihave there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law: where

no law, noinjustice. Force, and fraud, are in war the two cardinal virtues, Justice,

and injustice are none of the faculties neither of the body, nor mind. If they

‘were, they might be in aman that were alone in the world, as well ashis senses,

and passions. They are quali 10 men in society. notin solitude, It

is consequent also to the same condition, that there be no propriety, no domin-

jon, no mine and thine distinct; but only that to be every man’s, that he can get;

and for so long, as he can keep it. And thus much for the il condition, which

‘man by mere nature is actually paced in; though witha possibilty to come out

of it, consisting partly in che passions, partly in hs reason,

‘The passions that incline men to peace, are fear of death; desire of such

things as are necessary to commodious living; and a hope by their industry 0

‘obtain them, And reason suggesteth convenient articles of peace, upon which

‘men may be drawn to agreement. These articles, are they, which otherwise are

called the Laws of Nature

(From Levee with inod by CA. Gaskin (Oxford Unies Pres, Of,

1996), 82-6 st published 65]

=

“To understand political power aright, and desive i rom its original, we must,

consider what estate all men are naturally in, and that i, a state of perfect fee-

dom wo order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons they

‘think fit, within the bounds ofthe aw of Nature, without asking eave or de-

pending upon the will oF any other man,

‘state also of equality wherein all the power and jrisdition is reciprocal,

‘no one having more than another, there being nothing more evident than that

creatures of the seme species and rank, promiscuously bora ol the same ad-

‘vantages of Nature, andthe use ofthe same faculties, shouldakso be equal one

JOHN LOCKE 15

amongst another, without subordination or subjection,

‘master of themall should, by any manifest declaration of his

another, and confer on him, by an evident and clear appoint

doubted right to dominion and sovereigat

Butthough thisbea:

in that state have an uncontrollable liberty to dispose of his person or posses

sions, yet he has not liberty to destroy himself, or so much as.

possession, but where some nobler use than its bare prese

‘The state of Nature has a law of Nature o govern it, whi

and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind who

health, liberty or possessions; for men being.

nipotent and in

sent into the world by His order and about His business; they ate Hs property,

‘whose workmanship they are made to

sure, And, being furnished with ike faculties, sharing

(Nature, there cannot be supposed:

authorise us to destroy one another

so by the like reason, when his

the as much ashe can to pre

to-do justice on an offender, ake

(othe preservation of the life the liberty.

‘men may be

trained from invading others’ rights, and from

‘one another, and the law of Nature be observed, which willeththe

Peace and preservation of all mankind, the execution of the law of Nature isin

that state put into every man's hands, whereby every one has. right to punish

the traysgressors ofthat law to sucha degree as may hinderits violation, Forthe

Jaw of Nature would, as all other laws that concern men in this world, bein vain

if there were nobody thatin the state of Nature hada pawer to execute that law,

and thereby preserve the innocent and restrain offenders; andi any one in the

state of Nature may punish another for any evil he has done, every one may do

so Forin that state of perfect equality where naturally there isno superiority of

Jurisdiction of one over another, what any may do in prosecution of that kaw,

‘every one must needs havea right todo.

‘And thus inthe state of Nature, one man comesby apawer overanother, but

yetnoabsolute or arbitrary power to usea criminal, when he has got him in his

hhands, according to the passionate heats or boundless extravaganicy

will, but only to retribute to him so far as calm reason and conscience di

‘what is proportionate to his transgression, which is so much as may serve for

reparation and restraint. For these two are the only reasons why one man may

lawfully doharmco: Which is thar we call ponishment. In transgressing

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- (GR No L-15972) Kwong Sing v. City of ManilaDocumento9 pagine(GR No L-15972) Kwong Sing v. City of ManilacreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of ManilaDocumento18 pagine9 Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of ManilaJOHN NICHOLAS PALMERANessuna valutazione finora

- Read - A Definition of ArtDocumento4 pagineRead - A Definition of ArtcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Heugens2009 PDFDocumento26 pagineHeugens2009 PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Berger, P. 1963. An Invitation To Sociology - A Humanistic Perspective.Documento15 pagineBerger, P. 1963. An Invitation To Sociology - A Humanistic Perspective.creamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Stat 101 SyllabusDocumento2 pagineStat 101 SyllabuscreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Polsc 180 Matrix PDFDocumento4 paginePolsc 180 Matrix PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- 110 ReviewerDocumento6 pagine110 ReviewercreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Fourteen Points - Woodrow WilsonDocumento2 pagineFourteen Points - Woodrow WilsonPraveen Půff TilakaratneNessuna valutazione finora

- Polsc 120 NotesDocumento2 paginePolsc 120 NotescreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosen and Wolff 2a, 2b and 2cDocumento34 pagineRosen and Wolff 2a, 2b and 2ccreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Essence of Cuban Missile CrisisDocumento30 pagineThe Essence of Cuban Missile Crisissparroweyes100% (8)

- Salient Points of House Sub-Committee ProposalsDocumento36 pagineSalient Points of House Sub-Committee ProposalsRapplerNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept Analysis PDFDocumento9 pagineConcept Analysis PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Handout - Quick Tips For ASA Style PDFDocumento2 pagineHandout - Quick Tips For ASA Style PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Report Equipment DamageDocumento2 pagineReport Equipment DamageYousif_AbdalhalimNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Analyze PoetryDocumento50 pagineHow To Analyze PoetrycreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Taj Mahal Pop Up CardDocumento1 paginaTaj Mahal Pop Up CardLemuel Reyes0% (1)

- InquiryDocumento5 pagineInquirycreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Candidates For GraduationDocumento15 pagineCandidates For GraduationcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- SEA 30 Ferry & Foot Tour of Old ManilaDocumento1 paginaSEA 30 Ferry & Foot Tour of Old ManilacreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

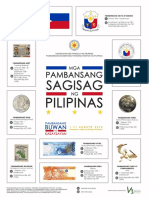

- NationalSymbols PDFDocumento2 pagineNationalSymbols PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Research QuestionsDocumento2 pagineDeveloping Research QuestionsglamisNessuna valutazione finora

- UPCD Dental Services Clinical FeesDocumento2 pagineUPCD Dental Services Clinical FeescreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- 8Documento27 pagine8VineetYadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Probability Concepts and Applications Chapter Provides Teaching ExamplesDocumento13 pagineProbability Concepts and Applications Chapter Provides Teaching ExamplesadowNessuna valutazione finora

- Dewey - Pattern of Inquiry PDFDocumento10 pagineDewey - Pattern of Inquiry PDFcreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Housing Characteristics in The Philippines: Sarah B. Cabug St. Columban CollegeDocumento9 pagineHousing Characteristics in The Philippines: Sarah B. Cabug St. Columban CollegecreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- Housing Characteristics in The Philippines: Sarah B. Cabug St. Columban CollegeDocumento9 pagineHousing Characteristics in The Philippines: Sarah B. Cabug St. Columban CollegecreamyfrappeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Baseball Cutoff and Backup Responsibilities - Pitchers: No Matter What The Play, You Always Have A Responsibility!Documento17 pagineBaseball Cutoff and Backup Responsibilities - Pitchers: No Matter What The Play, You Always Have A Responsibility!Antoine FoingNessuna valutazione finora

- MR Peabody S ApplesDocumento9 pagineMR Peabody S Applesedortizg100% (4)

- A Talent Management Case Study: Major League Baseball's Quest For Super KeepersDocumento14 pagineA Talent Management Case Study: Major League Baseball's Quest For Super KeepersPavithra ChandramohanNessuna valutazione finora

- MoneyBall ReactionDocumento1 paginaMoneyBall ReactionShane Vincent CavañasNessuna valutazione finora

- 3-3 D Box PlayDocumento49 pagine3-3 D Box PlayRoy WallNessuna valutazione finora

- Youth Pitching Guidelines f9j1h7sDocumento6 pagineYouth Pitching Guidelines f9j1h7sapi-242640330Nessuna valutazione finora

- Plug CatcherDocumento2 paginePlug CatcherFabricio0% (1)

- Handed It To Me On A Platter, and That Wasn't My Fault": Idiom Examples Hit The Books: On The BallDocumento15 pagineHanded It To Me On A Platter, and That Wasn't My Fault": Idiom Examples Hit The Books: On The BallManoj KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Ppt. SB History 4Documento11 paginePpt. SB History 4LYCHA SHAINE ESPIRITUNessuna valutazione finora

- Mexican Whiteboy EssayDocumento3 pagineMexican Whiteboy Essayapi-666588628Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Chicago Cubs 60 Game ScheduleDocumento1 pagina2020 Chicago Cubs 60 Game ScheduleYolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tee Ball Practice Plans and Drills - v1Documento23 pagineTee Ball Practice Plans and Drills - v1Tad ThiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Items - PZwikiDocumento45 pagineItems - PZwikiStal FeralNessuna valutazione finora

- Collision-Theory WebquestDocumento3 pagineCollision-Theory Webquestapi-252514594Nessuna valutazione finora

- BAF3MU Unit 2 Activity 5 - Harry TiemanDocumento4 pagineBAF3MU Unit 2 Activity 5 - Harry TiemanHarry Tieman100% (3)

- Diego Cabrera The Litte League World Series Guided NotesDocumento4 pagineDiego Cabrera The Litte League World Series Guided NotesDiego CabreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Rishit Vimadalal and Jaisal Baath Rishit Vimadalal and Jaisal BaathDocumento18 pagineRishit Vimadalal and Jaisal Baath Rishit Vimadalal and Jaisal BaathRishitVimadalalNessuna valutazione finora

- Cricket ProjectDocumento20 pagineCricket ProjectAdil AB100% (2)

- Texas Instruments TI 30X IIS ManualDocumento118 pagineTexas Instruments TI 30X IIS ManualfaqmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Murder Mystery Riddles - Barry SlogeskyDocumento4 pagineMurder Mystery Riddles - Barry SlogeskyIgor VitionNessuna valutazione finora

- (KT) Corset GBSB - Denim Bustier TopDocumento12 pagine(KT) Corset GBSB - Denim Bustier TopSara GarzonNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic Sentences PDFDocumento18 pagineTopic Sentences PDFLeynard UncianoNessuna valutazione finora

- MLB Payroll AnalysisDocumento3 pagineMLB Payroll AnalysisOdessaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Playing Court Is A Rectangle Measuring 18m X 9Documento3 pagineThe Playing Court Is A Rectangle Measuring 18m X 9miralona relevoNessuna valutazione finora

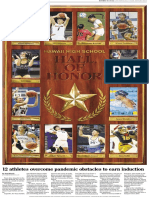

- 2022 Hawaii Hall of HonorDocumento1 pagina2022 Hawaii Hall of HonorHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNessuna valutazione finora

- Year 9 Physical and Health Practical Unit - Striking and FieldingDocumento8 pagineYear 9 Physical and Health Practical Unit - Striking and Fieldingapi-295369824Nessuna valutazione finora

- Koyama K. - Minami A. - Jiu Jitsu The Effective Japanese Mode of Self-DefenseDocumento99 pagineKoyama K. - Minami A. - Jiu Jitsu The Effective Japanese Mode of Self-DefenseSebastián100% (1)

- Week 2 Formative ActivitiesDocumento3 pagineWeek 2 Formative ActivitiesEvelyn Anays MöntenegröNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Optimizing Physical Education (H.O.P.E)Documento11 pagineHealth Optimizing Physical Education (H.O.P.E)Mr. CRAFTNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay MLB Salary CapDocumento10 pagineEssay MLB Salary Capapi-609516607Nessuna valutazione finora