Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Angara v. Electoral Commission

Caricato da

Wresen AnnTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Angara v. Electoral Commission

Caricato da

Wresen AnnCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Angara v.

Electoral Commission

Angara v. Electoral Commission

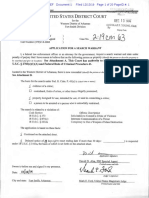

G.R. No. L-45081 July 15, 1936

Laurel, J.

Facts:

In the elections of September 17, 1935, the petitioner, Jose A. Angara, and the

respondents, Pedro Ynsua, Miguel Castillo and Dionisio Mayor, were candidates voted for the

position of member of the National Assembly for the first district of the Province of Tayabas.

On October 7, 1935, the provincial board of canvassers, proclaimed the petitioner as

member-elect of the National Assembly for the said district, for having received the most number of

votes.

On December 8, 1935, the herein respondent Pedro Ynsua filed before the Electoral

Commission a “Motion of Protest” against the election of the herein petitioner, Jose A. Angara, being

the only protest filed after the passage of Resolutions No. 8 aforequoted, and praying, among other-

things, that said respondent be declared elected member of the National Assembly for the first

district of Tayabas, or that the election of said position be nullified.

Issue:

Has the Supreme Court jurisdiction over the Electoral Commission and the subject matter

of the controversy upon the foregoing related facts, and in the affirmative?

Held:

Yes. The Electoral Commission, as we shall have occasion to refer hereafter, is a

constitutional organ, created for a specific purpose, namely to determine all contests relating to the

election, returns and qualifications of the members of the National Assembly. Although the Electoral

Commission may not be interfered with, when and while acting within the limits of its authority, it

does not follow that it is beyond the reach of the constitutional mechanism adopted by the people

and that it is not subject to constitutional restrictions. The Electoral Commission is not a separate

department of the government, and even if it were, conflicting claims of authority under the

fundamental law between department powers and agencies of the government are necessarily

determined by the judiciary in justifiable and appropriate cases. The Supreme Court has jurisdiction

over the Electoral Commission and the subject matter of the present controversy for the purpose of

determining the character, scope and extent of the constitutional grant to the Electoral Commission

as “the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the members of

the National Assembly.”

Issue:

Has the said Electoral Commission acted without or in excess of its jurisdiction in

assuming to the cognizance of the protest filed the election of the herein petitioner notwithstanding

the previous confirmation of such election by resolution of the National Assembly?

Held:

Section 4 of Article VI of the 1935 Constitution which provides:

SEC. 4. There shall be an Electoral Commission composed of three Justice of the Supreme Court

designated by the Chief Justice, and of six Members chosen by the National Assembly, three of

whom shall be nominated by the party having the largest number of votes, and three by the party

having the second largest number of votes therein. The senior Justice in the Commission shall be its

Chairman. The Electoral Commission shall be the sole judge of all contests relating to the election,

returns and qualifications of the members of the National Assembly.

The Electoral Commission is the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns

and qualifications of members of the National Assembly. Under the organic law prevailing before the

present Constitution went into effect, each house of the legislature was respectively the sole judge of

the elections, returns, and qualifications of their elective members.

The 1935 Constitution has transferred all the powers previously exercised by the legislature

with respect to contests relating to the elections, returns and qualifications of its members, to the

Electoral Commission. Such transfer of power from the legislature to the Electoral Commission was

full, clear and complete, and carried with it ex necesitate rei the implied power inter alia to prescribe

the rules and regulations as to the time and manner of filing protests.

The avowed purpose in creating the Electoral Commission was to have an independent

constitutional organ pass upon all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of

members of the National Assembly, devoid of partisan influence or consideration, which object

would be frustrated if the National Assembly were to retain the power to prescribe rules and

regulations regarding the manner of conducting said contests.

Section 4 of article VI of the Constitution repealed not only section 18 of the Jones Law

making each house of the Philippine Legislature respectively the sole judge of the elections, returns

and qualifications of its elective members, but also section 478 of Act No. 3387 empowering each

house to prescribe by resolution the time and manner of filing contests against the election of its

members, the time and manner of notifying the adverse party, and bond or bonds, to be required, if

any, and to fix the costs and expenses of contest.

Confirmation by the National Assembly of the election is contested or not, is not essential

before such member-elect may discharge the duties and enjoy the privileges of a member of the

National Assembly. Confirmation by the National Assembly of the election of any member against

whom no protest had been filed prior to said confirmation, does not and cannot deprive the Electoral

Commission of its incidental power to prescribe the time within which protests against the election of

any member of the National Assembly should be filed.

Based on the foregoing, the Electoral Commission was acting within the legitimate

exercise of its constitutional prerogative in assuming to take cognizance of the protest filed by the

respondent Pedro Ynsua against the election of the herein petitioner Jose A. Angara, and that the

resolution of the National Assembly of December 3, 1935 can not in any manner toll the time for

filing protests against the elections, returns and qualifications of members of the National Assembly,

nor prevent the filing of a protest within such time as the rules of the Electoral Commission might

prescribe.

Doctrine:

The separation of powers is a fundamental principle in our system of government. It

obtains not through express provision but by actual division in our Constitution. Each department of

the government has exclusive cognizance of matters within its jurisdiction, and is supreme within its

own sphere. But it does not follow from the fact that the three powers are to be kept separate and

distinct that the Constitution intended them to be absolutely unrestrained and independent of each

other. The Constitution has provided for an elaborate system of checks and balances to secure

coordination in the workings of the various departments of the government. For example, the Chief

Executive under our Constitution is so far made a check on the legislative power that this assent is

required in the enactment of laws. This, however, is subject to the further check that a bill may

become a law notwithstanding the refusal of the President to approve it, by a vote of two-thirds or

three-fourths, as the case may be, of the National Assembly. The President has also the right to

convene the Assembly in special session whenever he chooses. On the other hand, the National

Assembly operates as a check on the Executive in the sense that its consent through its

Commission on Appointments is necessary in the appointments of certain officers; and the

concurrence of a majority of all its members is essential to the conclusion of treaties. Furthermore, in

its power to determine what courts other than the Supreme Court shall be established, to define their

jurisdiction and to appropriate funds for their support, the National Assembly controls the judicial

department to a certain extent. The Assembly also exercises the judicial power of trying

impeachments. And the judiciary in turn, with the Supreme Court as the final arbiter, effectively

checks the other departments in the exercise of its power to determine the law, and hence to declare

executive and legislative acts void if violative of the Constitution. (Garcia v. Macaraig)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Constitution of the Republic of ChinaDa EverandConstitution of the Republic of ChinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hrs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. CADocumento23 pagineHrs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. CARomeo de la CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Inherent Powers of the State: Police, Eminent Domain & TaxationDocumento12 pagine3 Inherent Powers of the State: Police, Eminent Domain & TaxationFRANCO, Monique P.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Civpro Cases (Batch 1) : Ledesma, Sumulong and Quintos, For Appellants. J. C. Knudson, For AppelleeDocumento39 pagineCivpro Cases (Batch 1) : Ledesma, Sumulong and Quintos, For Appellants. J. C. Knudson, For AppelleeAngelika GacisNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Vs EstipularDocumento3 pagineRepublic Vs EstipularMoon BeamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Gustillo Vs Dela CruzDocumento5 pagineGustillo Vs Dela CruzCARLITO JR. ACERONNessuna valutazione finora

- Llorente v. Sandiganbayan DigestDocumento2 pagineLlorente v. Sandiganbayan DigestDan Christian Dingcong CagnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Cagayan Valley Enterprise Vs CA 179 SCRA 218Documento8 pagineCagayan Valley Enterprise Vs CA 179 SCRA 218Chino CabreraNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re VinzonDocumento1 paginaIn Re VinzonAdrianne BenignoNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 131755. October 25, 1999Documento11 pagineG.R. No. 131755. October 25, 1999Augieray D. MercadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Francisco C. Eizmendi Jr. vs. Teodorico P. Fernandez (Full Text, Word Version)Documento16 pagineFrancisco C. Eizmendi Jr. vs. Teodorico P. Fernandez (Full Text, Word Version)Emir MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. Mario Case DigestDocumento1 paginaPeople v. Mario Case DigestDexter LedesmaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. Feliciano, G.R. No. 196735, May 5, 2014Documento6 paginePeople v. Feliciano, G.R. No. 196735, May 5, 2014Kael MarmaladeNessuna valutazione finora

- Estopina Vs Lodrigo and Carpio-Morales Vs BinayDocumento2 pagineEstopina Vs Lodrigo and Carpio-Morales Vs BinayBarrrMaidenNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs Salas Case DigestDocumento3 paginePeople Vs Salas Case Digestmaushi abinalNessuna valutazione finora

- Pascual v. BallesterosDocumento2 paginePascual v. BallesterosAnsai Claudine CaluganNessuna valutazione finora

- Appeals Court Role in Criminal CasesDocumento12 pagineAppeals Court Role in Criminal CasesKristine JoyNessuna valutazione finora

- REM CrimPro 2023 BarDocumento108 pagineREM CrimPro 2023 BarDannah Louise Bonifacio100% (1)

- Court Rules Notice to Quit Not Required to Establish JurisdictionDocumento10 pagineCourt Rules Notice to Quit Not Required to Establish JurisdictionVienna Mantiza - PortillanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule 111 Gosiaco V ChingDocumento2 pagineRule 111 Gosiaco V ChingShane FulguerasNessuna valutazione finora

- Angara v. Electoral Commission - 45081 - StatconDocumento3 pagineAngara v. Electoral Commission - 45081 - StatconJan Chrys MeerNessuna valutazione finora

- Francisco vs. House of Representatives: TOPIC: Political QuestionDocumento3 pagineFrancisco vs. House of Representatives: TOPIC: Political QuestionArlando G. ArlandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Atok Finance v Court of AppealsDocumento2 pagineAtok Finance v Court of AppealsChilzia RojasNessuna valutazione finora

- All AreasDocumento648 pagineAll AreasGladys Morada100% (1)

- 1 - CABRERAvsPSA - Vicedo - Lloyd DavidDocumento2 pagine1 - CABRERAvsPSA - Vicedo - Lloyd DavidLloyd David P. Vicedo100% (1)

- Lawyer's Duty to Provide Legal Services and Represent Indigent ClientsDocumento11 pagineLawyer's Duty to Provide Legal Services and Represent Indigent ClientsnchlrysNessuna valutazione finora

- DAR Administrative Order No. 9 upheld in exempting livestock farm from CARP coverageDocumento5 pagineDAR Administrative Order No. 9 upheld in exempting livestock farm from CARP coverageJOHAYNIENessuna valutazione finora

- BM 1154 Haron MeilingDocumento2 pagineBM 1154 Haron MeilingApril DigasNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ321 NotesDocumento13 pagineCLJ321 NotesChriz Jhon LeysonNessuna valutazione finora

- Leviste v. AlamedaDocumento4 pagineLeviste v. AlamedaRalph Christian Lusanta FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- Remedial Law Bar Questions 2006-2013Documento38 pagineRemedial Law Bar Questions 2006-2013Ramir FamorcanNessuna valutazione finora

- Digests On JurisdictionDocumento16 pagineDigests On JurisdictionRZ ZamoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Pp. Vs Patricio AmigoDocumento3 paginePp. Vs Patricio AmigoAngel CabanNessuna valutazione finora

- De Guzman Vs SisonDocumento1 paginaDe Guzman Vs SisontynapayNessuna valutazione finora

- People V PurisimaDocumento1 paginaPeople V PurisimaCarissa CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Canon 8: Court Upholds Attorney in ContemptDocumento50 pagineCanon 8: Court Upholds Attorney in ContemptSM BAr100% (1)

- Chavez v. Judicial and Bar CouncilDocumento2 pagineChavez v. Judicial and Bar CouncilKreezelNessuna valutazione finora

- StatconDocumento299 pagineStatconruben diwasNessuna valutazione finora

- Neypes v. CA, G.R. No. 141524 (2005)Documento8 pagineNeypes v. CA, G.R. No. 141524 (2005)Keyan MotolNessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of Latayan Vs TanDocumento1 paginaHeirs of Latayan Vs TanNC BergoniaNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 129928, 25 August 2005 Misamis Occidental II Cooperative, Inc. v. David FactsDocumento2 pagineG.R. No. 129928, 25 August 2005 Misamis Occidental II Cooperative, Inc. v. David FactsChupsNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 1 Review NotesDocumento33 pagineConstitutional Law 1 Review NotesAoiNessuna valutazione finora

- City of Baguio vs. MarcosDocumento2 pagineCity of Baguio vs. MarcosLance LagmanNessuna valutazione finora

- People vs. Esureña (374 SCRA 424 GR 142727 January 23, 2002)Documento1 paginaPeople vs. Esureña (374 SCRA 424 GR 142727 January 23, 2002)Abdulateef SahibuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulep v. Legal Clinic 223 SCRA 378Documento24 pagineUlep v. Legal Clinic 223 SCRA 378AnonymousNessuna valutazione finora

- Meneses vs. Secretary of Agrarian Reform, G.R. No. 156304, October 23, 2006.Documento4 pagineMeneses vs. Secretary of Agrarian Reform, G.R. No. 156304, October 23, 2006.Caleb Josh PacanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 Florencio Eugenio Vs Executive SecretaryDocumento3 pagine15 Florencio Eugenio Vs Executive SecretaryCuycuy100% (1)

- Pacana-Gonzales V CA Gr150908Documento2 paginePacana-Gonzales V CA Gr150908Adi LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Gaerlan vs. CatubigDocumento4 pagineGaerlan vs. CatubigonryouyukiNessuna valutazione finora

- Civ Pro ReviewerDocumento88 pagineCiv Pro ReviewerHazel Alcaraz Robles100% (1)

- Barrameda vs. BarbaraDocumento5 pagineBarrameda vs. BarbaraAJ AslaronaNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 G.R. No. L-46228Documento3 pagine15 G.R. No. L-46228MARY CHRISTINE JOY E. BAQUIRINGNessuna valutazione finora

- Valley Golf & Country Club, Inc., Petitioner, vs. Rosa O. Vda. de Caram, Respondent. G.R. No. 158805 - April 16, 2009 FactsDocumento26 pagineValley Golf & Country Club, Inc., Petitioner, vs. Rosa O. Vda. de Caram, Respondent. G.R. No. 158805 - April 16, 2009 FactsSham GaerlanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aquino V ComelecDocumento16 pagineAquino V ComelecJanMikhailPanerioNessuna valutazione finora

- REQUISITES FOR CRIMINAL JURISDICTIONDocumento35 pagineREQUISITES FOR CRIMINAL JURISDICTIONJoanna Marie AlfarasNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digests On BankingDocumento15 pagineCase Digests On BankingMaria Monica GulaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 2018 Legal Ethics USC ReviewerDocumento93 pagine2017 2018 Legal Ethics USC ReviewerPlease I Need The File100% (1)

- Trillanes vs. Pimentel 566 SCRA 471Documento3 pagineTrillanes vs. Pimentel 566 SCRA 471Luna BaciNessuna valutazione finora

- La Naval Drug Corp. vs. CADocumento1 paginaLa Naval Drug Corp. vs. CAKanglawNessuna valutazione finora

- Fernando Lopez Vs Gerardo Roxas FactsDocumento14 pagineFernando Lopez Vs Gerardo Roxas FactsJenny HabasNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Cases CrimproDocumento18 pagineResearch Cases CrimproWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Article 838Documento10 pagineArticle 838Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict of Laws DigestsDocumento23 pagineConflict of Laws DigestsWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Mejorada DoctrineDocumento1 paginaMejorada DoctrineWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Sections 73 78Documento26 pagineSections 73 78Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Juris Case Digests 2Documento11 pagineJuris Case Digests 2Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Cases CrimproDocumento18 pagineResearch Cases CrimproWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Sections 73-78: Professor: Reported By: Wresen Ann DC. JavaluyasDocumento26 pagineSections 73-78: Professor: Reported By: Wresen Ann DC. JavaluyasWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Sections 73-78: Professor: Reported By: Wresen Ann DC. JavaluyasDocumento26 pagineSections 73-78: Professor: Reported By: Wresen Ann DC. JavaluyasWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- 2-5. Pestilos v. GenerosoDocumento2 pagine2-5. Pestilos v. GenerosoJovz Bumohya100% (1)

- G GGGGG GGGGGDocumento1 paginaG GGGGG GGGGGWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Ee EeeeeeeeeeeeeeeDocumento1 paginaEe EeeeeeeeeeeeeeeWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Villasenor Vs Abano DigestDocumento2 pagineVillasenor Vs Abano DigestWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Sec.5 Bail, when discretionary Rule 114 Criminal ProcedureDocumento2 pagineSec.5 Bail, when discretionary Rule 114 Criminal ProcedureWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Callanta Vs VillanuevaDocumento1 paginaCallanta Vs VillanuevaWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- People V Donato DigestDocumento1 paginaPeople V Donato DigestWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- People V Burgos DigestDocumento2 paginePeople V Burgos DigestWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- BBB BBBBBB BBBBBBDocumento1 paginaBBB BBBBBB BBBBBBWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs EdanoDocumento3 paginePeople Vs EdanoWresen Ann100% (1)

- Corpo Case Digest 2Documento12 pagineCorpo Case Digest 2Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Crmprodigest113 114Documento5 pagineCrmprodigest113 114Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- People VsDocumento2 paginePeople VsWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- A AaaaaaaaaaaaDocumento1 paginaA AaaaaaaaaaaaWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- GGGG GGGG GGGGG GGGGGDocumento1 paginaGGGG GGGG GGGGG GGGGGWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- L LLLLL LLLLLDocumento1 paginaL LLLLL LLLLLWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo Case Digest 2Documento12 pagineCorpo Case Digest 2Wresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- BBBBBB BBBBBB BBBBBBDocumento1 paginaBBBBBB BBBBBB BBBBBBWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- As To Corporate Name Philippine First Insurance Company, Inc. Maria Carmen Hartigan, CGH, and O. EngkeeDocumento35 pagineAs To Corporate Name Philippine First Insurance Company, Inc. Maria Carmen Hartigan, CGH, and O. EngkeeWresen AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim DigestDocumento2 pagineCrim DigestWresen Ann50% (2)

- Article III Bill of RightsDocumento22 pagineArticle III Bill of RightsCfc-sfc Naic Chapter100% (1)

- Democrats and The Death Penalty - An Analysis of State DemocraticDocumento85 pagineDemocrats and The Death Penalty - An Analysis of State DemocraticSahil Sharma AttriNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocumento7 pagineRhetorical Analysisapi-300196513Nessuna valutazione finora

- Faith and Frenzy Book ReviewDocumento1 paginaFaith and Frenzy Book ReviewJeet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Arab SpringDocumento24 pagineArab SpringGiselle QuilatanNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Cherokee Nation of Okla., 480 U.S. 700 (1987)Documento7 pagineUnited States v. Cherokee Nation of Okla., 480 U.S. 700 (1987)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Jalandhar Edition JLE 12 September 2015Documento24 pagineJalandhar Edition JLE 12 September 2015Ramanjaneyulu GVNessuna valutazione finora

- FMLA Lawsuit DechertDocumento18 pagineFMLA Lawsuit DechertMatthew Seth SarelsonNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.4 - Wartenbert, Thomas E. - The Concept of Power in Feminist Theory (En)Documento17 pagine3.4 - Wartenbert, Thomas E. - The Concept of Power in Feminist Theory (En)Johann Vessant Roig100% (1)

- Municipality of San Narciso Vs Mendez Sr. DigestDocumento2 pagineMunicipality of San Narciso Vs Mendez Sr. DigestMark MlsNessuna valutazione finora

- Preface: Social Protection For Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento2 paginePreface: Social Protection For Sustainable DevelopmentUNDP World Centre for Sustainable DevelopmentNessuna valutazione finora

- Adlof HitlerDocumento65 pagineAdlof HitlerMuhammad Nomaan ❊100% (1)

- Freedom of Press ConceptsDocumento77 pagineFreedom of Press ConceptsPrashanth MudaliarNessuna valutazione finora

- Bureaucratic LeadershipDocumento32 pagineBureaucratic LeadershipR. Mega Mahmudia100% (1)

- Barangay Resolution Authorizing SignatoriesDocumento2 pagineBarangay Resolution Authorizing SignatoriesNoe S. Elizaga Jr.83% (12)

- 300 Academicians - International Solidarity StatementDocumento16 pagine300 Academicians - International Solidarity StatementFirstpostNessuna valutazione finora

- Jabatan Kerja Raya Negeri Selangor Darul Ehsan Tingkat 1, BangunanDocumento2 pagineJabatan Kerja Raya Negeri Selangor Darul Ehsan Tingkat 1, Bangunantoeyfik100% (1)

- MUN ProcedureDocumento3 pagineMUN ProcedurePromit Biswas100% (4)

- Hygiene Promotion Project Progress and PlansDocumento11 pagineHygiene Promotion Project Progress and PlansRaju AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- SS 120Documento5 pagineSS 120Nagarajan Karupanan RastaNessuna valutazione finora

- 20 Years of Democracy - The State of Human Rights in South Africa 2014Documento12 pagine20 Years of Democracy - The State of Human Rights in South Africa 2014Tom SchumannNessuna valutazione finora

- Maximum Rocknroll #06Documento72 pagineMaximum Rocknroll #06matteapolis100% (2)

- Arthakranti - Economic Rejuvenation of IndiaDocumento67 pagineArthakranti - Economic Rejuvenation of IndiaPrasen GundavaramNessuna valutazione finora

- RWDSDocumento20 pagineRWDSJ RohrlichNessuna valutazione finora

- Symbolic Interactionism Definitely Finished-WovideoDocumento28 pagineSymbolic Interactionism Definitely Finished-Wovideoangstrom_unit_Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concessions A 4Documento1 paginaConcessions A 4Inam AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Richard K. Betts - Politicization of IntelligenceDocumento29 pagineRichard K. Betts - Politicization of IntelligencebertaramonasilviaNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 6320822314900391483Documento21 pagine5 6320822314900391483SK NAJBUL HOQUENessuna valutazione finora

- COS CommunityTables Blueprint 0Documento21 pagineCOS CommunityTables Blueprint 0Ed PraetorianNessuna valutazione finora

- Kitchen Sink RealismDocumento7 pagineKitchen Sink RealismCristina CrisuNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge International University: Final AssignmentDocumento4 pagineKnowledge International University: Final AssignmentHassan BasarallyNessuna valutazione finora