Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

482 After CRL Revision Dismissed Maintainable

Caricato da

sreevarshaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

482 After CRL Revision Dismissed Maintainable

Caricato da

sreevarshaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.

Perumal on 2 April, 2014

Madras High Court

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

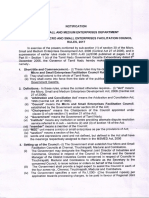

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS

DATED: 02.04.2014

CORAM:

THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE C.T. SELVAM

CRL.O.P.Nos.8352 and 6556 of 2014

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014

D.Simpson .. Petitioner

vs.

S.T.Perumal .. Respondent

Crl.O.P.No.6556/2014

S.T.Perumal .. Petitioner

vs.

1.The State rep. By

The Inspector of Police (L&O),

Nellankarai Police Station,

Nellankarai, Chennai.

2. Simpson .. Respondents

Criminal Original Petitions filed

Section

under 482 Cr.P.C. Praying (i) to compound the offence

For Petitioner in

Crl.OP.8352/2014 and

R-2 in Crl.OP.6556/2014 : Mr.N.Anand Venkatesh

For Respondent in

Crl.OP.8352/2014 and

Petitioner in Crl.OP.

6556/2014 : Mr.R.Subburaj

For R-2 in

Crl.OP.6556/2014 : Mr.C.Emalias

Additional Public Prosecutor

*****

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 1

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

O R D E R

Petitioner in Crl.O.P.No.8352 of 2014 faces prosecution for offence under Section 138 of the

Negotiable Instruments Act, in C.C.No.3359 of 2006 on the file of learned IX Metropolitan

Magistrate, Saidapet, Chennai, pursuant to a complaint preferred by the respondent in

Crl.OP.No.8352/2014. The said case ended in a conviction and the petitioner was sentenced to one

year imprisonment, with a further direction to pay Rs.4,00,000/- as compensation, in default, to

undergo 3 months imprisonment, under judgment dated 08.08.2008. The petitioner / accused

preferred appeal as against the said conviction before III Additional Sessions Judge, City Civil Court,

Chennai, and the appellate Court confirmed the order of trial Court, vide judgment dated

10.02.2009. A further revision was moved before this Court in Crl.R.C.No.273 of 2009, which was

dismissed under order dated 15.11.2011, thereby confirming the judgments of the Courts below.

2.The present petition in Crl.O.P.No.8352 of 2014 is filed informing a compromise arrived at

between the petitioner / accused and the respondent / de facto complainant and of the respondent

having received a sum of Rs.4,00,000/- in full quit and further that the respondent has also agreed

to co-operate for compounding the offence committed by the petitioner / accused. A joint memo of

compromise dated 01.04.2014 signed both by the petitioner / accused and the respondent / de facto

complainant and attested by two witnesses confirms such position.

3.Towards supporting the submission of learned counsel for petitioner / accused that principle of

functus officio would not apply even after the dismissal of the revision filed before this Court, he

relied on the judgment of the Apex Court in Damodar S.Prabhu vs. Sayed Babalal H., (2010) 5 SCC

663. The following paragraphs in the said decision are relevant.

"15. The compounding of the offence at later stages of litigation in cheque bouncing cases has also

been held to be permissible in a recent decision of this Court, reported as K.M. Ibrahim v. K.P.

Mohammed7 wherein Kabir, J. has noted (at SCC p. 802, paras 13-14):

™3. As far as the non obstante clause included in Section 147 of the 1881 Act is concerned, the 1881

Act being a special statute, the provisions of Section 147 will have an overriding effect over the

provisions of the Code relating to compounding of offences.

14. It is true that the application under Section 147 of the Negotiable Instruments Act was made by

the parties after the proceedings had been concluded before the appellate forum. However, Section

147 of the aforesaid Act does not bar the parties from compounding an offence under Section 138

even at the appellate stage of the proceedings. Accordingly, we find no reason to reject the

application under Section 147 of the aforesaid Act even in a proceeding under Article 136 of the

Constitution.

16. It is evident that the permissibility of the compounding of an offence is linked to the perceived

seriousness of the offence and the nature of the remedy provided. On this point we can refer to the

following extracts from an academic commentary [cited from: K.N.C. Pillai, R.V. Kelkar s Criminal

Procedure, Fifth Edn. (Lucknow: Eastern Book Company, 2008) at p. 444]:

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 2

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

™7.2. Compounding of offences. A crime is essentially a wrong against the society and the State.

Therefore any compromise between the accused person and the individual victim of the crime

should not absolve the accused from criminal responsibility. However, where the offences are

essentially of a private nature and relatively not quite serious, the Code considers it expedient to

recognise some of them as compoundable offences and some others as compoundable only with the

permission of the court.

17. In a recently published commentary, the following observations have been made with regard to

the offence punishable under Section 138 of the Act [cited from: Arun Mohan, Some thoughts

towards law reforms on the topic of Section 138, Negotiable Instruments Act Tackling an avalanche

of cases (New Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 2009) at p. 5]:

Unlike that for other forms of crime, the punishment here (insofar as the complainant is

concerned) is not a means of seeking retribution, but is more a means to ensure payment of money.

The complainant s interest lies primarily in recovering the money rather than seeing the drawer of

the cheque in jail. The threat of jail is only a mode to ensure recovery. As against the accused who is

willing to undergo a jail term, there is little available as remedy for the holder of the cheque.

If we were to examine the number of complaints filed which were compromised or settled

before the final judgment on one side and the cases which proceeded to judgment and conviction on

the other, we will find that the bulk was settled and only a miniscule number continued.

18. It is quite obvious that with respect to the offence of dishonour of cheques, it is the

compensatory aspect of the remedy which should be given priority over the punitive aspect. There is

also some support for the apprehensions raised by the learned Attorney General that a majority of

cheque bounce cases are indeed being compromised or settled by way of compounding, albeit during

the later stages of litigation thereby contributing to undue delay in justice delivery. The problem

herein is with the tendency of litigants to belatedly choose compounding as a means to resolve their

dispute. Furthermore, the written submissions filed on behalf of the learned Attorney General have

stressed on the fact that unlike Section 320 CrPC, Section 147 of the Negotiable Instruments Act

provides no explicit guidance as to what stage compounding can or cannot be done and whether

compounding can be done at the instance of the complainant or with the leave of the court.

19. As mentioned earlier, the learned Attorney General s submission is that in the absence of

statutory guidance, parties are choosing compounding as a method of last resort instead of opting

for it as soon as the Magistrates take cognizance of the complaints. One explanation for such

behaviour could be that the accused persons are willing to take the chance of progressing through

the various stages of litigation and then choose the route of settlement only when no other route

remains. While such behaviour may be viewed as rational from the viewpoint of litigants, the hard

facts are that the undue delay in opting for compounding contributes to the arrears pending before

the courts at various levels. If the accused is willing to settle or compromise by way of compounding

of the offence at a later stage of litigation, it is generally indicative of some merit in the

complainant s case. In such cases it would be desirable if parties choose compounding during the

earlier stages of litigation. If however, the accused has a valid defence such as a mistake, forgery or

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 3

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

coercion among other grounds, then the matter can be litigated through the specified forums.

20. It may be noted here that Section 143 of the Act makes an offence under Section 138 triable by a

Judicial Magistrate, First Class (JMFC). After trial, the progression of further legal proceedings

would depend on whether there has been a conviction or an acquittal.

In the case of conviction, an appeal would lie to the Court of Sessions under Section 374(3)(a) CrPC;

thereafter a revision to the High Court under Sections 397/401 CrPC and finally a petition before the

Supreme Court, seeking special leave to appeal under Section 136 of the Constitution of India. Thus,

in case of conviction there will be four levels of litigation.

In the case of acquittal by JMFC, the complainant could appeal to the High Court under Section

378(4) CrPC, and thereafter for special leave to appeal to the Supreme Court under Article 136. In

such an instance, therefore, there will be three levels of proceedings.

21. With regard to the progression of litigation in cheque bouncing cases, the learned Attorney

General has urged this Court to frame guidelines for a graded scheme of imposing costs on parties

who unduly delay compounding of the offence. It was submitted that the requirement of deposit of

the costs will act as a deterrent for delayed composition, since at present, free and easy

compounding of offences at any stage, however belated, gives an incentive to the drawer of the

cheque to delay settling the cases for years. An application for compounding made after several

years not only results in the system being burdened but the complainant is also deprived of effective

justice. In view of this submission, we direct that the following guidelines be followed:

THE GUIDELINES

(i) In the circumstances, it is proposed as follows:

(a) That directions can be given that the writ of summons be suitably modified making it clear to the

accused that he could make an application for compounding of the offences at the first or second

hearing of the case and that if such an application is made, compounding may be allowed by the

court without imposing any costs on the accused.

(b) If the accused does not make an application for compounding as aforesaid, then if an application

for compounding is made before the Magistrate at a subsequent stage, compounding can be allowed

subject to the condition that the accused will be required to pay 10% of the cheque amount to be

deposited as a condition for compounding with the Legal Services Authority, or such authority as the

court deems fit.

(c) Similarly, if the application for compounding is made before the Sessions Court or a High Court

in revision or appeal, such compounding may be allowed on the condition that the accused pays 15%

of the cheque amount by way of costs.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 4

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

(d) Finally, if the application for compounding is made before the Supreme Court, the figure would

increase to 20% of the cheque amount.

22. Let it also be clarified that any costs imposed in accordance with these Guidelines should be

deposited with the Legal Services Authority operating at the level of the court before which

compounding takes place. For instance, in case of compounding during the pendency of proceedings

before a Magistrate s Court or a Court of Session, such costs should be deposited with the District

Legal Services Authority. Likewise, costs imposed in connection with composition before the High

Court should be deposited with the State Legal Services Authority and those imposed in connection

with composition before the Supreme Court should be deposited with the National Legal Services

Authority."

4.Learned counsel also relied upon the judgment of the Kerala High Court in Sabu George vs. Home

Secretary, Department of Home Affairs, New Delhi, (2007 Cri.L.J.1865). In the said decision, in

paragraphs 15 to 26, it is observed as follows:

15. But then, such a conclusion also creates further problems. If the verdict of guilty, conviction and

sentence have become final, which Court would accept the same so as to avoid execution of the

sentence, which has become final. If the trial/appeal/revision is already over, such original, trial and

revisional court would become functus officio and they will not have jurisdiction to alter their

verdicts and to convert the verdict of guilty and conviction to a deemed acquittal under Section

320(8). The language of Section 362 Cr.P.C. which I extract below, makes the position clear. S.362.

Court not to alter judgment. - Save as otherwise provided by this Code or by any other law for the

time being in force, no Court, when it has signed its judgment or final order disposing of a case, shall

alter or review the same except to correct a clerical or arithmetical error." Therefore the judgment,

which has already been rendered, cannot be altered by the trial court, appellate court or the

revisional court. The decision in State of Kerala v. M.M. Manikantan Nair (AIR 2001 SC 2145) is

clear authority for the proposition that a Court, which has become functus officio, cannot thereafter

pass any orders in such a case. I extract para 7 of the said judgment for this proposition:

" This Court in Hari Singh Mann v. Harbhajan Singh Bajwa, (2001) 1 SCC 169: (2000 AIR SCW

3848: AIR 2001 SC 43: 2001 Cri.LJ 128), held that Section 362 of the Criminal Procedure Code

mandates that no Court, when it has signed its judgment or final order disposing of a case shall alter

or review the same except to correct a clerical or an arithmetical error and that this section is based

on an acknowledged principle of law that once a matter is finally disposed of by a Court, the said

Court in the absence of a specific statutory provision becomes functus officio and disentitled to

entertain a fresh prayer for the same relief unless the former order of final disposal is set aside by

the Court of competent jurisdiction." (emphasis supplied) Therefore, it is evident that a trial,

appellate or revisional Court, which has become functus officio cannot accept a subsequent

composition and alter its own earlier judgment and convert the same to a deemed acquittal under

Section 320(8) Cr.P.C. It is unnecessary to refer to other precedents. Binding precedents of the

Supreme Court make it clear that a Court - Original, appellate or revisional, which has finally

disposed of the matter cannot thereafter exercise any such powers which it could have invoked and

exercised prior to such final disposal.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 5

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

16. If the trial, appellate and revisional court cannot do the same and the composition is legally

permissible, the question necessarily will have to be considered as to which court can and in what

manner the accused, the offence against whom has been compounded in accordance with law, can

be saved from the trauma of suffering the sentence.

17. It is here that the next question arises as to whether powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. can be

invoked by this Court to give effect to such a composition which has been legally arrived at, but for

the acceptance of which, there is no specific stipulation of law. Section 482 Cr.P.C. reads as follows:-

"S. 482. Saving of inherent powers of High Court. - Nothing in this Code shall be deemed to limit or

affect the inherent powers of the High Court to make such orders as may be necessary to give effect

to any order under this Code, or to prevent abuse of the process of any Court or otherwise to secure

the ends of justice."

18. Precedents galore to indicate the sweep, width and amplitude of the inherent powers of this

Court under Section 482 Cr.P.C. Section 482 does not really confer any power on the High Court

exercising criminal jurisdiction. It only saves the inherent powers of the High Court, which was

always there. Ex debito justitiae such powers can be invoked and such powers were always available

with the court. The width and amplitude of such powers must necessarily instill in the mind of the

Court the need to be circumspect. But such powers are not fettered by any stipulations of the Code.

If there be any doubt on this proposition, it will be apposite to refer to the decision in Raj Kapoor v.

State (1980) 1 SCC 43). Justice Krishna Iyer in paragraph 10 of that decision refers to the powers

under Section 482 Cr.P.C. in the following words:

"10. The first question is as to whether the inherent power of the High Court under Section 482

stand repelled when the revisional power under Section 397 overlaps. The opening words of Section

482 contradict this contention because nothing of the Code, not even Section 397, can affect the

amplitude of the inherent power preserved in so many terms by the language of Section 482. Even

so, a general principle pervades this branch of law when a specific provision is made: easy resort to

inherent power is not right except under compelling circumstances. Not that there is absence of

jurisdiction but that inherent power should not invade areas set apart for specific power under the

same Code."

(emphasis supplied)

19. Later, the Supreme Court had occasion to specifically consider whether the stipulations under

Section 320 Cr.P.C. would fetter the powers of the High Court under Section 482 Cr.P.C. The

decision in B.S. Joshi v. State of Haryana (AIR 2003 SC 1386) makes the position clear and the

Supreme Court speaks thus through Justice Y.K. Sabharwal in paragraphs 8 and 15:

"8. It is, thus, clear that Madhu Limaye's case does not lay down any general proposition limiting

power of quashing the criminal proceedings or FIR or complaint as vested in S.482 of the code or

extraordinary power under Art.226 of the Constitution of India. We are, therefore, of the view that if

for the purpose of securing the ends of justice, quashing of FIR becomes necessary, S.320 would not

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 6

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

be a bar to the exercise of power of quashing, it is however, a different matter depending upon the

facts and circumstances of each case whether to exercise or not such a power."

"15. In view of the above discussion, we hold that in the High Court in exercise of its inherent powers

can quash criminal proceedings or FIR or complaint and S.320 of the Code does not limit or affect

the powers under S. 482 of the Code."

(emphasis supplied) These observations were made while considering the question of quashing an

F.I.R. But there is nothing to show that the principle will not apply when the question of quashing a

sentence which has become final is considered when the offence is legally compounded.

20. A Full Bench of this Court had looked at the sweep of the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C.,

though in a different context, and the rationale underlying in Section 482 Cr.P.C. is expressed by the

Full Bench in the following words in Moosa v. Sub Inspector of Police (2006 (1) KLT 552):

"No legislative enactment dealing with procedure can provide for all cases that may possibly arise.

Courts, therefore, have inherent powers apart from express provisions of law which are necessary

for proper discharge of functions and duties imposed upon them by law. In exercise of the powers

court would be justified to quash any proceedings if it finds that initiation or continuance of it

amounts to abuse of the process of court or quashing of these proceedings would otherwise serve the

ends of justice."

(emphasis supplied)

21. Having so understood the sweep of the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C., I need only mention

that the powers under Article 226/227 of the Constitution are coextensive if not wider in its sweep.

The powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. as also Article 226 and 227 of the Constitution are available

with the Court to do justice in a given case when the conscience of the Court is satisfied that powers

must be invoked.

22. It will be apposite to straight away look at Section 320 Cr.P.C. again. Section 320 does not

specifically refer to composition prior to the commencement of the prosecution or of composition

after the sentence has become final. Section 320, which must be reckoned as consolidating the law

relating to composition, does not specifically refer to pre-cognizance and post-finality (of

conviction) compositions. Section 320(9) Cr.P.C. only says that there shall be no composition except

in accordance with the provisions of Section 320 Cr.P.C. In as much as Section 320 does not

specifically refer to compositions - pre-cognizance or post-finality, and Section 320(1) only speaks of

composition without any fetters or limitations about time and stage, section 320(9) cannot be held

to fetter the powers in such situations.

23. The rationale underlying Section 482 Cr.P.C. is that the interests of justice may at times

transcend the interests of mere law. In the peculiar facts and circumstances of a given case when the

High Court considers it necessary, proper and fit and feels impelled and compelled to act in aid of

justice, it should not be without powers and helpless. While appreciating the width and amplitude of

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 7

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. this principle cannot be lost sight of. Of course if there is a

specific express bar or if the stipulations point to an implied bar, such powers cannot normally be

invoked.

24. We now come to the crucial question as to whether this court, having already disposed of the

revisions, can invoke the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. The revision has been disposed of and

the verdict of guilty, conviction and sentence have now become final. I have come across decisions

which stipulate that in view of Section 362, even this Court exercising original power as a criminal

court under Section 482 Cr.P.C., cannot go against the mandate of Section 362. The decision in Smt.

Sooraj Devi v. Pyare Lal & anr. (1981) 1 SCC 500) clearly holds that after the judgment is

pronounced, on the same facts powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. cannot be invoked in view of the

specific bar under Section 362. This position has been held repeatedly. In Hari Singh Mann v.

Harbhajan Singh Bajwa (AIR 2001 SC 43), it was held by the Supreme Court as follows in

paragraphs 8 and 9:

"8. xxx xxx The practice of filing miscellaneous petitions after the disposal of the main case and

issuance of fresh directions in such miscellaneous petitions by the High Court are unwarranted, not

referable to any statutory provision and in substance the abuse of the process of the Court.

9. There is no provision in the Code of Criminal Procedure authorising the High Court to review the

judgment W.P.C. No. 34540 of 2006 & connected cases passed either in exercise of its appellate or

revisional or original criminal jurisdiction. Such power cannot be exercised with the aid or under the

cloak of Section 482 of the Code."

In State of Kerala v. M.M.Manikantan Nair (AIR 2001 SC 2145) the Supreme Court held so in

paragraph 6:

"6. The Code of Criminal Procedure does not authorise the High Court to review its judgment or

order passed either in exercise of its appellate, revisional or original jurisdiction. Section 362 of the

Code prohibits the Court after it has signed its judgment or final order disposing a case from altering

or reviewing the said judgment or order except to correct a clerical or arithmetical error. This

prohibition is complete and no criminal Court can review its own judgment or order after it is

signed."

In Moti Lal v. State of Madhya Pradesh (AIR 1994 SC 1544) the Supreme Court held so in paragraph

2:

"2. Section 362 Cr.P.C. in clear terms lays down that the Court cannot alter judgment after the same

has been signed except to correct clerical or arithmetical errors. That being the position the High

Court had no jurisdiction under Section 482 Cr.P.C. to alter the earlier judgment."

In Damodaran v. State (1992 (2) KLT 165) and in Tanveer Aquil v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1990

Suppl. SCC 63) we find observations which suggest that a post revision composition cannot be

readily accepted. Those decisions, according to me, only reiterate the principle that a trial, appellate

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 8

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

or revisional court which is functus officio in respect of a subject matter cannot thereafter exercise

powers in respect of such disposed of matters in view of Section 362 Cr.P.C.

25. But these decisions cannot be held to cover a situation when post-revision there has been a

substantial change in the circumstances and a later request is made in a separate application under

Section 482 Cr.P.C. or Article 226 of 227 of the Constitution. That question was specifically

considered by the Supreme Court in Mostt. Simrikhia v. Smt. Dolley Mukherjee (1990 Crl.L.J. 1599).

In paragraph 2 of the said decision, the Supreme Court has observed thus:

"If there had been change in the circumstances of the case, it would be in order for the High Court to

exercise its inherent powers in the prevailing circumstances and pass appropriate orders to secure

the ends of justice or to prevent the abuse of the process of the Court. Where there is no such

changed circumstances and the decision has to be arrived at on the facts that existed as on the date

of the earlier order, the exercise of the power to reconsider the same materials to arrive at different

conclusion is in effect a review, which is expressly barred under S.362."

26. In the instant cases, when the revision petition was disposed of by this Court, this circumstance -

that the parties settled the dispute and the complainant compounded the offence - was not there at

all. It is a subsequent change in circumstance. The decision in Mostt. Simrikhia (supra) squarely

applies. That was a case where an earlier application under Section 482 Cr.P.C. was dismissed, but

still the Supreme Court held that a change in circumstances is sufficient to justify the invocation of

the powers afresh under Section 482 Cr.P.C. notwithstanding the bar under Section 362 Cr.P.C. In

the instant case, the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. have not been sought to be invoked earlier.

Only the revisional powers were exercised. That is all the more the reason why under the changed

circumstances the extra ordinary inherent jurisdiction under Section 482 Cr.P.C. can be invoked. In

the light of the dictum in Mostt. Simrikhia earlier decisions rendered and subsequent decisions,

which do not refer to the said decision specifically and in which the opinion is expressed that the

powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C. cannot be invoked after disposal of the revision in view of the bar

under Section 362, cannot be held to lay down the law correctly.

5.In the light of the above judgments, as also the compromise entered into between parties,

Crl.O.P.No.8352 of 2014 shall stand allowed, with costs of Rs.25,000/- payable by the petitioner to

the Tamil Nadu State Legal Services Authority, within a period of two (2) weeks from the date of

receipt of a copy of this order.

6.In view of the order passed in Crl.O.P.No.8352 of 2014, Crl.O.P. No.6556 of 2014 shall stand

closed.

02.04.2014 Index :Yes Internet:Yes sra To

1.The Inspector of Police (L&O), Nellankarai Police Station, Nellankarai, Chennai.

2.The Public Prosecutor, High Court, Madras.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 9

Crl.O.P.No.8352/2014 vs S.T.Perumal on 2 April, 2014

C.T. SELVAM,J.

(sra) CRL.O.P.Nos.8352 and 6556 of 2014 02.04.2014

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/47230176/ 10

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Supreme Court Rules, 2013Documento106 pagineSupreme Court Rules, 2013Latest Laws TeamNessuna valutazione finora

- Special Fee Advocate EnrolmentDocumento21 pagineSpecial Fee Advocate EnrolmentsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nadigar Sangam JudgmentDocumento62 pagineNadigar Sangam JudgmentsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- VARGA D/10 or DASAMA "MAHAT PHALAM" DASAMSA OR KARMAMSA OR SWARGAMSADocumento11 pagineVARGA D/10 or DASAMA "MAHAT PHALAM" DASAMSA OR KARMAMSA OR SWARGAMSAANTHONY WRITER100% (3)

- Tamil Nadu Rules and FormDocumento6 pagineTamil Nadu Rules and FormsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iqbal Vs State of Kerala On 24 October, 2007Documento4 pagineIqbal Vs State of Kerala On 24 October, 2007sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arudha PadaDocumento16 pagineArudha PadaVaraha Mihira100% (11)

- Rajendran Vs State Rep. by Inspector of Police On 9 July, 2012Documento6 pagineRajendran Vs State Rep. by Inspector of Police On 9 July, 2012sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arudha PadaDocumento16 pagineArudha PadaVaraha Mihira100% (11)

- 8140 Decisive Battles TextDocumento18 pagine8140 Decisive Battles TextsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Puducherry RulesDocumento3 paginePuducherry RulessreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- P.danapal Vs State Rep. by On 23 March, 2015Documento6 pagineP.danapal Vs State Rep. by On 23 March, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sodexo SVC India Pvt. LTD Vs State of Maharashtra and Ors On 9 December, 2015Documento9 pagineSodexo SVC India Pvt. LTD Vs State of Maharashtra and Ors On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court examines school certificate in juvenile caseDocumento8 pagineSupreme Court examines school certificate in juvenile casesreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Drugs&Cosmetic ActDocumento284 pagineDrugs&Cosmetic ActsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri CH - Narasimha Rao & Ors Vs Land Acquisition Officer Eluru & ... On 9 December, 2015Documento4 pagineSri CH - Narasimha Rao & Ors Vs Land Acquisition Officer Eluru & ... On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Alamelu & Anr Vs State Rep - by Inspector of Police On 18 January, 2011Documento12 pagineAlamelu & Anr Vs State Rep - by Inspector of Police On 18 January, 2011sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unlawful AssemblyDocumento3 pagineUnlawful AssemblysreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- PDFDocumento356 paginePDFsreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- 750 Famous Motivational and Inspirational QuotesDocumento53 pagine750 Famous Motivational and Inspirational QuotesSaanchi AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Oil Corporation LTD Vs A.p.industrial Infractrcture ... On 9 December, 2015Documento8 pagineIndian Oil Corporation LTD Vs A.p.industrial Infractrcture ... On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pratap Kishore Panda & Ors Vs Agni Charan Das & Ors On 16 October, 2015Documento8 paginePratap Kishore Panda & Ors Vs Agni Charan Das & Ors On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Balu at Bal Subramaniam & Anr Vs State (U.T. of Pondicherry) On 16 October, 2015Documento6 pagineBalu at Bal Subramaniam & Anr Vs State (U.T. of Pondicherry) On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arumugha Pillai Vs Vadivel Pillai On 29 September, 1993Documento5 pagineArumugha Pillai Vs Vadivel Pillai On 29 September, 1993sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shailesh Dhairyawan Vs Mohan Balkrishna Lulla On 16 October, 2015Documento15 pagineShailesh Dhairyawan Vs Mohan Balkrishna Lulla On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rajvinder Singh Vs State of Haryana On 16 October, 2015Documento7 pagineRajvinder Singh Vs State of Haryana On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Veerenndra Kumar Dubey Vs Chief of Army Staff & Ors On 16 October, 2015Documento10 pagineVeerenndra Kumar Dubey Vs Chief of Army Staff & Ors On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kamal at Poorikamal & Anr Vs State of Tamil Nadu On 16 October, 2015Documento7 pagineKamal at Poorikamal & Anr Vs State of Tamil Nadu On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- (GROUP 1) ComelecDocumento57 pagine(GROUP 1) ComelecJeffy EmanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal Maxims With o 00 WharDocumento364 pagineLegal Maxims With o 00 WharSomashish Naskar100% (2)

- Holder and Holder in Due CourseDocumento7 pagineHolder and Holder in Due CourseartiNessuna valutazione finora

- Carpio V DorojaDocumento2 pagineCarpio V DorojaJian CerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- Alvin EJS With Sale LordanDocumento3 pagineAlvin EJS With Sale LordanAron JaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate law notes on companies limited by guaranteeDocumento7 pagineCorporate law notes on companies limited by guaranteeTayo AkinkuolieNessuna valutazione finora

- Cartel Penalty and Leniency Under The Competition Act, 2002Documento4 pagineCartel Penalty and Leniency Under The Competition Act, 2002tanveer1908Nessuna valutazione finora

- Applicant - S Information Sheet (ActiveOne) PDFDocumento4 pagineApplicant - S Information Sheet (ActiveOne) PDFmaris dinglasaNessuna valutazione finora

- Greenwich Ballistics v. Jamison InternationalDocumento10 pagineGreenwich Ballistics v. Jamison InternationalPriorSmartNessuna valutazione finora

- Majlis Peguam v Sunil Singh Gill 2004 CA ruling upholds Samantha Murthi precedentDocumento2 pagineMajlis Peguam v Sunil Singh Gill 2004 CA ruling upholds Samantha Murthi precedentNURUL HIDAYATNessuna valutazione finora

- Dimaampao: Doctrine of Symbiotic Relationship: Taxes AreDocumento3 pagineDimaampao: Doctrine of Symbiotic Relationship: Taxes AreCelestino LawNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract Law For IP Lawyers: Mark Anderson, Lisa Allebone and Mario SubramaniamDocumento14 pagineContract Law For IP Lawyers: Mark Anderson, Lisa Allebone and Mario SubramaniamJahn MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Trademark Laws in IndiaDocumento4 pagineTrademark Laws in IndiaPurnima MathurNessuna valutazione finora

- Northumbria Legal Studies Working Paper SeriesDocumento12 pagineNorthumbria Legal Studies Working Paper SeriesPranay BhardwajNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Evidence ACT 1872: ConspiracyDocumento15 pagineIndian Evidence ACT 1872: Conspiracychhaayaachitran akshuNessuna valutazione finora

- BIR v GMCC Ruling on Prescription PeriodDocumento8 pagineBIR v GMCC Ruling on Prescription PeriodJaysonNessuna valutazione finora

- Comelec Resolution 10015Documento27 pagineComelec Resolution 10015Kriska Herrero Tumamak100% (1)

- MEDLINE MANAGEMENT, INC. and GRECOMAR SHIPPING AGENCY v. GLICERIA ROSLINDA and ARIEL ROSLINDADocumento3 pagineMEDLINE MANAGEMENT, INC. and GRECOMAR SHIPPING AGENCY v. GLICERIA ROSLINDA and ARIEL ROSLINDAEsp BsbNessuna valutazione finora

- Space Opera Character SheetDocumento195 pagineSpace Opera Character SheetSeth BlevinsNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal Ethics Questionnaire AnswersDocumento17 pagineLegal Ethics Questionnaire AnswersNiel Brian VillarazoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kul 2. Maxwell's Equations in Integral FormDocumento11 pagineKul 2. Maxwell's Equations in Integral FormRico BernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Notification of West Bengal Police Sub Inspector Lady Sub Inspector PostsDocumento5 pagineNotification of West Bengal Police Sub Inspector Lady Sub Inspector PostsTechnical4uNessuna valutazione finora

- IPremier Case PowerPoint FinalDocumento19 pagineIPremier Case PowerPoint FinalEnrica Melissa Panjaitan100% (1)

- Legal Ethics Case DigestDocumento82 pagineLegal Ethics Case DigestJay ann JuanNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. O'CochlainDocumento46 paginePeople v. O'CochlainGerald Javison LudasNessuna valutazione finora

- DECS Service ManualDocumento8 pagineDECS Service ManualMoira SarmientoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bible Baptist Church vs. CADocumento3 pagineBible Baptist Church vs. CAirene anibongNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Act 11648 Increasing Age of Statutory RapeDocumento3 pagineRepublic Act 11648 Increasing Age of Statutory Rapemc.rockz14Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2009 Banking LawDocumento29 pagine2009 Banking LawAnge Buenaventura Salazar100% (1)

- Civpro NotesDocumento33 pagineCivpro NotesBuen LibetarioNessuna valutazione finora