Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Hypocobalaminemia PDF

Caricato da

soff4ikaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Hypocobalaminemia PDF

Caricato da

soff4ikaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CONSULT THE EXPERTS h METABOLIC DISEASE h PEER REVIEWED

Hypocobalaminemia

Leonard E. Jordan, DVM

M. Katherine Tolbert, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (SAIM)

University of Tennessee

Background & Pathophysiology cause cobalamin deficiency (Table,

Cobalamin (ie, vitamin B12) is a water- next page). Dogs and cats with exocrine

soluble vitamin that plays an important pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) may have

role in DNA and RNA synthesis, amino decreased production of intrinsic factor.

acid (eg, cysteine, homocysteine) metab- Intestinal diseases (eg, inflammatory

olism, and energy production. Following bowel disease, food-responsive enteropa-

ingestion of cobalamin-rich nutrients thy, intestinal lymphoma, dysbiosis,

(eg, fish, poultry, eggs, red meat, dairy lymphangiectasia) can result in compro-

products), cobalamin first binds to mised ileal function and inadequate

haptocorrin, which is produced in both absorption of cobalamin.1,2 Familial

the salivary gland and the stomach. In cobalamin deficiency resulting from a

the duodenum, cobalamin is bound to loss-of-function mutation in the receptor

intrinsic factor—a protein produced responsible for intestinal cobalamin

primarily in the pancreas of dogs and absorption is an uncommon cause of

cats—and is later absorbed in the distal hypocobalaminemia but should be con-

small intestine. sidered in young patients presented with

GI and neurologic signs, especially in pre-

Any disease that affects the production disposed breeds such as giant schnauzers,

of intrinsic factor or interferes with the Australian shepherd dogs, border collies, EPI = exocrine pancreatic

insufficiency

intestinal absorption of cobalamin can beagles, shar-peis, and Komondors.3,4

July 2018 cliniciansbrief.com 65

CONSULT THE EXPERTS h METABOLIC DISEASE h PEER REVIEWED

History & Clinical Signs occurring with pancreatic and GI dis-

Common signs of cobalamin deficiency ease, clinical signs induced by familial

in dogs and cats include GI signs (eg, hypocobalaminemia are responsive to

anorexia, weight loss), which often cobalamin supplementation alone.5 In

mimic those observed in animals with one case report, a border collie with

chronic GI disease; thus, the clinician selective cobalamin malabsorption was

may not immediately consider cobala- presented with hepatic encephalopathy

min deficiency as a contributing factor. secondary to hypocobalaminemia,

Additional clinical signs of hypocobala- which resolved following cobalamin

minemia can include failure to thrive, supplementation.6 In another report, a

immunodeficiency, and neuropathies. Yorkshire terrier with selective cobala-

These clinical signs may be more com- min malabsorption was presented with

monly observed in dogs with familial seizures that also resolved with paren-

cobalamin deficiency. Unlike those teral cobalamin supplementation.7 Thus,

cobalamin deficiency should be consid-

ered in any animal presented with

chronic GI signs, especially when in

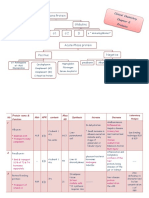

TABLE combination with neurologic signs.

DISEASES ASSOCIATED Diagnosis

WITH LOW COBALAMIN Hypocobalaminemic cats often do not

respond as readily as normocobalamin-

emic cats to treatment of the primary

Disease Diagnostic Test(s) disease unless supplemented with

cobalamin; this is unproven but, in the

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency Trypsinogen-like authors’ clinical experience, is also sus-

immunoreactivity pected in hypocobalaminemic dogs.

Pancreatitis Pancreatic lipase Thus, cobalamin deficiency is an import-

immunoreactivity, ant clinical consideration in any patient

abdominal ultrasonography presented with signs of chronic enteropa-

thy or pancreatic disease. Diagnosis of

Inflammatory bowel disease Intestinal biopsy and

histopathologic examination hypocobalaminemia requires measure-

ment of serum cobalamin concentrations.

Intestinal lymphoma Intestinal biopsy and However, patients may have serum cobal-

histopathologic amin levels that are low-normal (250-350

examination ± immunopheno-

ng/L) and still have critically low tissue

typing, PCR for antigen receptor

rearrangements (PARR) cobalamin concentrations. In these cases,

evaluating biomarkers of tissue cobala-

Lymphangiectasia Abdominal imaging, intestinal min deficiency (eg, methylmalonic acid

biopsy and histopathologic

[MMA], homocysteine) may provide

examination

more insight, as these biomarkers often

Selective cobalamin Genetic testing for some patients increase with tissue cobalamin deficiency

malabsorption (eg, evaluation for cubilin [CUBN] in dogs.4,8-10 In cats, MMA may be a better

gene mutation), urine MMA indicator of tissue cobalamin deficiency

testing

as compared with homocysteine.6

66 cliniciansbrief.com July 2018

Treatment & Management

Cobalamin therapy (see Suggested Reading, page 51, for dose, fre-

quency, and administration information) should be instituted when

serum concentrations fall below 250 ng/L. Additional consideration

for supplementation is recommended in patients with a low-normal

serum cobalamin (250-350 ng/L) and/or signs of intestinal or pancre-

atic disease. Hypocobalaminemia secondary to GI disease has anecdot-

ally been thought to require parenteral supplementation of cobalamin

until the intestinal or pancreatic disease was appropriately treated JOIN DR. M. KATHERINE

because of the inability to absorb cobalamin or produce intrinsic fac-

tor, respectively. However, recent research has suggested that oral

TOLBERT FOR AN

administration of cobalamin in dogs and cats with chronic enteropa- UPDATE ON ACID

thies11,12 and dogs with EPI13 is effective in restoring normal cobalamin SUPPRESSION AT

concentrations. This may be secondary to enhanced passive absorption

of cobalamin along the length of the small intestine.

NEW YORK VET

Prognosis & Prevention New York City • November 8-9, 2018

The prognosis for hypocobalaminemic patients depends largely on the

underlying disease process and how the patient responds to treatment

of the primary disease. Low cobalamin concentration is associated New York Vet speakers are

with shorter survival with some diseases, including EPI and multi- selected because of their passion

centric lymphoma.13,14 Lack of recovery for dogs with chronic diarrhea for exceptional patient care and

due to inflammatory idiopathic or neoplastic disease may also be more their experience with the

likely when severe hypocobalaminemia (<200 ng/L) is present.15 The challenges you tackle in practice

benefit of supplementation in these disease states has not been defini- every day.

tively proven; however, it is recommended to evaluate the patient’s

serum cobalamin concentration and provide supplementation when Join M. Katherine Tolbert, DVM, PhD,

DACVIM (SAIM), on November 8

hypocobalaminemia is identified. Prognosis for familial cobalamin

to learn how to maximize

deficiency is good with long-term supplementation.

famotidine’s effectiveness in

patients with acid suppression.

Clinical Follow-Up & Monitoring

Daily oral cobalamin supplementation or a 6-week course of weekly

parenteral supplementation followed by a single injection 30 days later

and retesting after 30 days is recommended.1,16 Some patients, espe- REGISTER TODAY AT

cially those with EPI or ongoing intestinal disease, may require contin- NEWYORKVET.COM FOR $199

ued monthly cobalamin supplementation. If resolution of the primary WITH PROMO CODE NYVET199.

disease cannot be achieved, more frequent cobalamin administration

may be required. If remission of the underlying disease (eg, food-re- Don’t hesitate! This offer

sponsive enteropathy) is achieved, long-term supplementation may not expires July 27, 2018.

be necessary; however, re-evaluation of the patient’s serum cobalamin

concentration is recommended if disease relapse occurs. n

EPI = exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

MMA = methylmalonic acid See page 51 for references.

July 2018 cliniciansbrief.com 67

CONSULT THE EXPERTS h CONTINUED FROM PAGE 67

References

1. Ruaux CG. Cobalamin in companion animals: diagnostic marker, defi- 10. Rossi G, Breda S, Giordano A, et al. Association between hypocobalami-

ciency states and therapeutic implications. Vet J. 2013;196(2):145-152. naemia and hyperhomocysteinaemia in dogs. Vet Rec. 2013;172(14):365.

2. Marks S. Diarrhea. In: Washabau RJ, Day MJ, eds. Canine and Feline 11. Torresson L, Steiner JM, Olmedal G, Larsen M, Suchodolski JS, Spill-

Gastroenterology. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:103-104. mann T. Oral cobalamin supplementation in cats with hypocobalami-

3. Giger U, Smith J. Immunodeficiencies and infectious diseases. In: naemia: a retrospective study. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19(12):1302-1306.

Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, 12. Toresson L, Steiner JM, Suchodolski JS, Spillmann T. Oral cobalamin

MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1108. supplementation in dogs with chronic enteropathies and hypocobala-

4. Bishop MA, Xenoulis PG, Berghoff N, Grützner N, Suchodolski JS, Steiner minemia. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30(1):101-107.

JM. Partial characterization of cobalamin deficiency in Chinese Shar 13. Toresson L, Steiner JM, Suchodolski JS, Spillmann T. Oral cobalamin

Peis. Vet J. 2012;191(1):41-45. supplementation in dogs with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (ab-

5. Fyfe JC, Giger U, Hall CA, et al. Inherited selective intestinal cobala- stract). J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(4):1283.

min malabsorption and cobalamin deficiency in dogs. Pediatr Res. 14. Batchelor DJ, Noble PJ, Taylor RH, Cripps PJ, German AJ. Prognostic

1991;29(1):24-31. factors in canine exocrine pancreatic insufficiency: prolonged survival is

6. Battersby IA, Giger U, Hall EJ. Hyperammonaemic encephalopathy likely if clinical remission is achieved. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(1):54-60.

secondary to selective cobalamin deficiency in a juvenile Border collie. 15. Cook AK, Wright ZM, Suchodolski JS, Brown MR, Steiner JM. Prevalence

J Small Anim Pract. 2005;46(7):339-344. and prognostic impact of hypocobalaminemia in dogs with lymphoma.

7. McLauchlan G, McLaughlin A, Sewell AC, Bell R. Methylmalonic aciduria J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235(12):1437-1441.

secondary to selective cobalamin malabsorption in a Yorkshire terrier. 16. Texas A&M Gastrointestinal Laboratory. Cobalamin: diagnostic use and

J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2015;51(4):285-288. therapeutic considerations. Gastrointestinal Library website. http://

8. Ruaux CG, Steiner JM, Williams DA. Early biochemical and clinical vetmed.tamu.edu/gilab/research/cobalamin-information. Accessed

responses to cobalamin supplementation in cats with signs of gastro- October 4, 2017.

intestinal disease and severe hypocobalaminemia. J Vet Intern Med.

2005;19(2):155-160. Suggested Reading

9. Berghoff N, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM. Association between Texas A&M Gastrointestinal Laboratory. Cobalamin: diagnostic use and

serum cobalamin and methylmalonic acid concentrations in dogs. therapeutic considerations. Gastrointestinal Library website. http://

Vet J. 2012;191(3):306-311. vetmed.tamu.edu/gilab/research/cobalamin-information. Accessed

October 4, 2017.

TOP 5 h CONTINUED FROM PAGE 62

9. Weese JS, Dick H, Willey BM, et al. Suspected transmission of Escherichia coli from dogs and owners. Braz J Microbiol.

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between domestic pets 2016;47(1):150-158.

and humans in veterinary clinics and in the household. Vet Microbiol. 20. Damborg P, Morsing MK, Petersen T, Bortolaia V, Guardabassi L.

2006;115(1-3):148-155. CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli in dog faeces from

10. Lefebvre SL, Reid-Smith RJ, Waltner-Toews D, Weese JS. Incidence of public gardens. Acta Vet Scand. 2015;57(1):83.

acquisition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium 21. Cui L, Lei L, Lv Y, et al. blaNDM-1-producing multidrug-resistant

difficile, and other health-care-associated pathogens by dogs that Escherichia coli isolated from a companion dog in China. J Glob

participate in animal-assisted interventions. J Am Vet Med Assoc. Antimicrob Resist. 2017;13:24-27.

2009;234(11):1404-1417.

22. González-Torralba A, Oteo J, Asenjo A, Bautista V, Fuentes E, Alós JI.

11. Lefebvre SL, Weese JS. Contamination of pet therapy dogs with MRSA Survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in

and Clostridium difficile. J Hosp Infect. 2009;72(3):268-269. companion dogs in Madrid, Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

12. Borriello SP, Honour P, Turner T, Barclay F. Household pets as a 2016;60(4):2499-2501.

potential reservoir for Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Pathol. 23. Belas A, Salazar AS, Gama LT, Couto N, Pomba C. Risk factors for faecal

1983;36(1):84-87. colonisation with Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum and

13. Struble AL, Tang YJ, Kass PH, Gumerlock PH, Madewell BR, Silva J Jr. plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases in dogs. Vet Rec. 2014;175(8):202.

Fecal shedding of Clostridium difficile in dogs: a period prevalence 24. Wedley AL, Dawson S, Maddox TW, et al. Carriage of antimicrobial

survey in a veterinary medical teaching hospital. J Vet Diagn Invest. resistant Escherichia coli in dogs: prevalence, associated risk factors

1994;6(3):342-347. and molecular characteristics. Vet Microbiol. 2017;199:23-30.

14. Weese J, Finley R, Reid-Smith RR, Janecko N, Rousseau J. Evaluation 25. Joffe DJ, Schlesinger DP. Preliminary assessment of the risk of

of Clostridium difficile in dogs and the household environment. Salmonella infection in dogs fed raw chicken diets. Can Vet J.

Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(8):1100-1104. 2002;43(6):441-442.

15. Galdys AL, Nelson JS, Shutt KA, et al. Prevalence and duration of 26. Lefebvre SL, Reid-Smith R, Boerlin P, Weese JS. Evaluation of the risks

asymptomatic Clostridium difficile carriage among healthy subjects in of shedding Salmonellae and other potential pathogens by therapy

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(7):2406-2409. dogs fed raw diets in Ontario and Alberta. Zoonoses Public Health.

16. Arroyo LG, Kruth SA, Willey BM, Staempfli HR, Low DE, Weese JS. PCR 2008;55(8-10):470-480.

ribotyping of Clostridium difficile isolates originating from human and 27. Leonard EK, Pearl DL, Janecko N, et al. Risk factors for carriage of

animal sources. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt 2):163-166. antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella spp and Escherichia coli in pet dogs

17. Lefebvre SL, Arroyo LG, Weese JS. Epidemic Clostridium difficile strain in from volunteer households in Ontario, Canada, in 2005 and 2006. Am J

hospital visitation dog. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(6):1036-1037. Vet Res. 2015;76(11):959-968.

18. Rupnik M. Is Clostridium difficile-associated infection a potentially 28. Lefebvre SL. Animal-Assisted Therapy Programs and Zoonoses [thesis].

zoonotic and foodborne disease? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(5): Guelph, Ontario, Canada: University of Guelph; 2013.

457-459. 29. Oehler RL, Velez AP, Mizrachi M, Lamarche J, Gompf S. Bite-related

19. Carvalho AC, Barbosa AV, Arais LR, Ribeiro PF, Carneiro VC, Cerqueira and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis.

AM. Resistance patterns, ESBL genes, and genetic relatedness of 2009;9(7):439-447.

July 2018 cliniciansbrief.com 51

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Rachel Joyce - A Snow Garden and Other Stories PDFDocumento118 pagineRachel Joyce - A Snow Garden and Other Stories PDFИгорь ЯковлевNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE1Documento1 paginaCASE1Daniel LamasonNessuna valutazione finora

- T.A.T.U. - Waste Management - Digital BookletDocumento14 pagineT.A.T.U. - Waste Management - Digital BookletMarieBLNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Cobalamin Status and Disorders of Cobalamin Metabolism in DogsDocumento16 pagineReview of Cobalamin Status and Disorders of Cobalamin Metabolism in DogsEduardo SantamaríaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cobalamin in Companion AnimalsDocumento8 pagineCobalamin in Companion AnimalsFlávia UchôaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Elderly Patients: Review SynthèseDocumento9 pagineVitamin B (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Elderly Patients: Review SynthèseMedranoReyesLuisinNessuna valutazione finora

- BR J Haematol - 2014 - DevaliaDocumento18 pagineBR J Haematol - 2014 - Devaliamariam.husseinjNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap139 PDFDocumento3 pagineChap139 PDFvivianNessuna valutazione finora

- The Functional Cobalamin (Vitamin B) - Intrinsic Factor Receptor Is A Novel Complex of Cubilin and AmnionlessDocumento8 pagineThe Functional Cobalamin (Vitamin B) - Intrinsic Factor Receptor Is A Novel Complex of Cubilin and AmnionlessantonNessuna valutazione finora

- Original Research: Aluminum Ingestion Promotes Colorectal Hypersensitivity in RodentsDocumento12 pagineOriginal Research: Aluminum Ingestion Promotes Colorectal Hypersensitivity in Rodentsechia srikandiNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Protein NotesDocumento4 pagine4 Protein NotesChitogeNessuna valutazione finora

- Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocumento1 paginaIrritable Bowel SyndromeYalin AbouhassiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture Notes: Clinical Chemistry of LiverDocumento38 pagineLecture Notes: Clinical Chemistry of LivershehnilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Megaloblastic AnemiasDocumento37 pagineMegaloblastic AnemiasL3mi DNessuna valutazione finora

- filePV 26 12 940 PDFDocumento9 paginefilePV 26 12 940 PDFzikryauliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpretations: How To Use Faecal Elastase TestingDocumento6 pagineInterpretations: How To Use Faecal Elastase TestingguschinNessuna valutazione finora

- Molecular Genetics and Metabolism: Fei Li, David Watkins, David S. RosenblattDocumento7 pagineMolecular Genetics and Metabolism: Fei Li, David Watkins, David S. RosenblattAndreea DamianNessuna valutazione finora

- Megalin and Cubilin in Renal Proximal Tubule 2Documento26 pagineMegalin and Cubilin in Renal Proximal Tubule 2Seun AdaramolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B12:: A Water Soluble Hematopoietic VitaminDocumento25 pagineVitamin B12:: A Water Soluble Hematopoietic Vitamindr. SheryarOrakzaiNessuna valutazione finora

- 06.2 Inborn Error of Metabolism - Iii B - Trans PDFDocumento10 pagine06.2 Inborn Error of Metabolism - Iii B - Trans PDFAshim AbhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bilirubin Metabolism and Liver Function Test by V e BoloyaDocumento35 pagineBilirubin Metabolism and Liver Function Test by V e BoloyaPrincewill SeiyefaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Elderly PatientsDocumento9 pagineVitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Elderly PatientsGrady ChristianNessuna valutazione finora

- Inborn Error of MetabolismDocumento55 pagineInborn Error of MetabolismRahil singh chauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Top 5 Causes of Passive Cervical FlexionDocumento7 pagineTop 5 Causes of Passive Cervical FlexionCabinet VeterinarNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathophysiology Hypoalbuminaemia.: Nephrotic SyndromeDocumento4 paginePathophysiology Hypoalbuminaemia.: Nephrotic SyndromegabyNessuna valutazione finora

- LFT 140330115634 Phpapp01Documento47 pagineLFT 140330115634 Phpapp01RahulNessuna valutazione finora

- Blood Loss: Acute Chronic Inadequate Production of Normal Blood CellsDocumento11 pagineBlood Loss: Acute Chronic Inadequate Production of Normal Blood CellsSheila Amor BodegasNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Liver Function: Key PointsDocumento16 pagineEvaluation of Liver Function: Key Pointsmanideep mungiNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in The Older Adult: C. Christine Orton, PHD, FNP-BCDocumento7 pagineVitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in The Older Adult: C. Christine Orton, PHD, FNP-BCAnis RanisNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 - Article 3Documento7 pagine3 - Article 3KHAOULANessuna valutazione finora

- MLS 111B Endterm LectureDocumento41 pagineMLS 111B Endterm LectureJohanna MarieNessuna valutazione finora

- en Paralytic Ileus in Vegetarian With PneumDocumento6 pagineen Paralytic Ileus in Vegetarian With PneumDanuNessuna valutazione finora

- 14.malabsorption SyndromesDocumento5 pagine14.malabsorption SyndromesPriyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary Nelsons Chapter 84Documento2 pagineSummary Nelsons Chapter 84Michael John Yap Casipe100% (1)

- Cobalamin DeficiencyDocumento19 pagineCobalamin DeficiencyAlloiBialba100% (1)

- Finals - Print - CC1 LabDocumento5 pagineFinals - Print - CC1 LabHazel Joyce Gonda RoqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Preer2010 PDFDocumento7 paginePreer2010 PDFJéssica MorenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Berberine On Human Gut BacteriaDocumento4 pagineImpact of Berberine On Human Gut Bacteriajlaczko2002Nessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal Jaundice: Bilirubin MetabolismDocumento2 pagineNeonatal Jaundice: Bilirubin MetabolismghsNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Function Tests: ReviewDocumento7 pagineEvaluation of Abnormal Liver Function Tests: ReviewfedlyNessuna valutazione finora

- 9.1 Liver Function TestsDocumento8 pagine9.1 Liver Function TestsGio Joaquin SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Megaloblastic AnaemiaDocumento31 pagineMegaloblastic AnaemiabassamhematolNessuna valutazione finora

- Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Intensive Care Nursery House Staff ManualDocumento5 pagineInborn Errors of Metabolism: Intensive Care Nursery House Staff ManualwarishNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypokalemia Nursing Care PlanDocumento2 pagineHypokalemia Nursing Care PlanIan Lelis100% (1)

- Liver Function TestDocumento9 pagineLiver Function TestFarah Krisna Sadavao AndangNessuna valutazione finora

- Albumin: Author: Carrie A. Phelps Editor: Jörg MayerDocumento1 paginaAlbumin: Author: Carrie A. Phelps Editor: Jörg MayerAisyah NurlanyNessuna valutazione finora

- Transes Act 7 CC LabDocumento7 pagineTranses Act 7 CC LabCiara PamonagNessuna valutazione finora

- AlbuminDocumento1 paginaAlbuminOfficial NutkopNessuna valutazione finora

- Serumalbuminandglobulin Id 14563Documento6 pagineSerumalbuminandglobulin Id 14563satriaarceusNessuna valutazione finora

- PharmacyDocumento16 paginePharmacyJow RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Jaundice 160318164012Documento47 pagineJaundice 160318164012Ritik MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- MALABSORPTIONDocumento3 pagineMALABSORPTIONZyra LagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Liver PathologyDocumento35 pagineLiver Pathologynhgwdwffp2Nessuna valutazione finora

- J of Small Animal Practice - 2024 - Dor - Efficacy and Tolerance of Oral Versus Parenteral Cyanocobalamin Supplement inDocumento12 pagineJ of Small Animal Practice - 2024 - Dor - Efficacy and Tolerance of Oral Versus Parenteral Cyanocobalamin Supplement in5bpwt89v9qNessuna valutazione finora

- Plasma Protein Albumins Globulins α 1 α 2 β: Prealbumin Albumin γ " immunoglobines"Documento7 paginePlasma Protein Albumins Globulins α 1 α 2 β: Prealbumin Albumin γ " immunoglobines"Lara MasriNessuna valutazione finora

- AntibioticsDocumento24 pagineAntibioticsAlba GonzálezNessuna valutazione finora

- Bilirubin Total CPDocumento4 pagineBilirubin Total CPLAB. GATOT SUBROTONessuna valutazione finora

- Beta Lactams LectureDocumento59 pagineBeta Lactams Lecturexmd6787qpqNessuna valutazione finora

- Proteins: Prepared By: Dayle Daniel G. Sorveto, RMT, MSMTDocumento64 pagineProteins: Prepared By: Dayle Daniel G. Sorveto, RMT, MSMTDayledaniel SorvetoNessuna valutazione finora

- Proteins: M. Zaharna Ckin. Chem. 2009Documento28 pagineProteins: M. Zaharna Ckin. Chem. 2009Ahmed GaberNessuna valutazione finora

- Leptin: Regulation and Clinical ApplicationsDa EverandLeptin: Regulation and Clinical ApplicationsSam Dagogo-Jack, MDNessuna valutazione finora

- A Simple Guide to Celiac Disease and Malabsorption DiseasesDa EverandA Simple Guide to Celiac Disease and Malabsorption DiseasesNessuna valutazione finora

- Atypical Hypoadrenocorticism in DogsDocumento1 paginaAtypical Hypoadrenocorticism in Dogssoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpretation of Parathyroid AbnormalitiesDocumento11 pagineInterpretation of Parathyroid Abnormalitiessoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Canine InsulinomaDocumento5 pagineCanine Insulinomasoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutritional Assessment in A Dog With Chronic Enteropathy PDFDocumento4 pagineNutritional Assessment in A Dog With Chronic Enteropathy PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypocobalaminemia PDFDocumento4 pagineHypocobalaminemia PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutritional Assessment in A Dog With Chronic Enteropathy PDFDocumento4 pagineNutritional Assessment in A Dog With Chronic Enteropathy PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Enucleation - Pharmacologic Ciliary Body Ablation of The EyeDocumento7 pagineEnucleation - Pharmacologic Ciliary Body Ablation of The Eyesoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intrahepatic Splenosis in A Labrador Retriever PDFDocumento4 pagineIntrahepatic Splenosis in A Labrador Retriever PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intrahepatic Splenosis in A Labrador Retriever PDFDocumento4 pagineIntrahepatic Splenosis in A Labrador Retriever PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- DD Exophthalmos-Buphthalmos-Proptosis PDFDocumento3 pagineDD Exophthalmos-Buphthalmos-Proptosis PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Proportion of Litters of Purebred Dogs Born by Cae PDFDocumento7 pagineProportion of Litters of Purebred Dogs Born by Cae PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arac 30 03 571 PDFDocumento17 pagineArac 30 03 571 PDFsoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Proportion of Litters of Purebred Dogs Born by CaeDocumento7 pagineProportion of Litters of Purebred Dogs Born by Caesoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- .Jo:R, DRMB - Rlla::Llst So.Documento14 pagine.Jo:R, DRMB - Rlla::Llst So.soff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- BrachypelmaDocumento5 pagineBrachypelmasoff4ikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 01-20 Optical Multiplexer and Demultiplexer BoardDocumento57 pagine01-20 Optical Multiplexer and Demultiplexer BoardDaler ShorahmonovNessuna valutazione finora

- VavDocumento8 pagineVavkprasad_56900Nessuna valutazione finora

- Us Navy To Evaluate Anti Submarine Warfare Training SystemDocumento2 pagineUs Navy To Evaluate Anti Submarine Warfare Training SystemVictor PileggiNessuna valutazione finora

- Solar Charge Controller: Solar Car Solar Home Solar Backpack Solar Boat Solar Street Light Solar Power GeneratorDocumento4 pagineSolar Charge Controller: Solar Car Solar Home Solar Backpack Solar Boat Solar Street Light Solar Power Generatorluis fernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Diabetic FootDocumento7 pagineAssessment of Diabetic FootChathiya Banu KrishenanNessuna valutazione finora

- MSDS DowthermDocumento4 pagineMSDS DowthermfebriantabbyNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Wildlife Conflict Resolution PDFDocumento9 pagineHuman Wildlife Conflict Resolution PDFdemiNessuna valutazione finora

- Coding Decoding Sheet - 01 1678021709186Documento9 pagineCoding Decoding Sheet - 01 1678021709186Sumit VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- 500 TransDocumento5 pagine500 TransRodney WellsNessuna valutazione finora

- Flow Zone Indicator Guided Workflows For PetrelDocumento11 pagineFlow Zone Indicator Guided Workflows For PetrelAiwarikiaar100% (1)

- Resume: Satyam KumarDocumento3 pagineResume: Satyam KumarEr Satyam Kumar KrantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Aquaculture Scoop May IssueDocumento20 pagineAquaculture Scoop May IssueAquaculture ScoopNessuna valutazione finora

- Ujian 1 THN 4Documento13 pagineUjian 1 THN 4Che Shuk ShukaNessuna valutazione finora

- The History of AstrologyDocumento36 pagineThe History of AstrologyDharani Dharendra DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Pusheen With Donut: Light Grey, Dark Grey, Brown, RoséDocumento13 paginePusheen With Donut: Light Grey, Dark Grey, Brown, RosémafaldasNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco Exercise 3answer Ans 1Documento8 pagineEco Exercise 3answer Ans 1Glory PrintingNessuna valutazione finora

- SAT Practice Test 10 - College BoardDocumento34 pagineSAT Practice Test 10 - College BoardAdissaya BEAM S.Nessuna valutazione finora

- V. Jovicic and M. R. Coop1997 - Stiffness, Coarse Grained Soils, Small StrainsDocumento17 pagineV. Jovicic and M. R. Coop1997 - Stiffness, Coarse Grained Soils, Small StrainsxiangyugeotechNessuna valutazione finora

- Maritime Management SystemsDocumento105 pagineMaritime Management SystemsAndika AntakaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Curvilinear MotionDocumento50 pagine3 Curvilinear Motiongarhgelh100% (1)

- OPTCL-Fin-Bhw-12Documento51 pagineOPTCL-Fin-Bhw-12Bimal Kumar DashNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics Unit 11 NotesDocumento26 paginePhysics Unit 11 Notesp.salise352Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On Traditional Medicinal Herbs Used by The Ethnic People of Goalpara District of Assam, North East IndiaDocumento6 pagineA Study On Traditional Medicinal Herbs Used by The Ethnic People of Goalpara District of Assam, North East IndiaDr. Krishna N. SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pitot/Static Systems: Flight InstrumentsDocumento11 paginePitot/Static Systems: Flight InstrumentsRoel MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Loads Considered For Design of BridgeDocumento45 pagineTypes of Loads Considered For Design of BridgeAbhishek100% (1)

- Minimalist KWL Graphic OrganizerDocumento2 pagineMinimalist KWL Graphic OrganizerIrish Nicole AlanoNessuna valutazione finora

- BIF-V Medium With Preload: DN Value 130000Documento2 pagineBIF-V Medium With Preload: DN Value 130000Robi FirdausNessuna valutazione finora

- Esterification Oil of WintergreenDocumento8 pagineEsterification Oil of WintergreenMaria MahusayNessuna valutazione finora