Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Synecdochic Fallacy 1981

Caricato da

gogunusedCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Synecdochic Fallacy 1981

Caricato da

gogunusedCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Synecdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society

by Stephen M, Weinstock

[Presented to the 67th annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, November 1981, Disneyland

California, as part of a panel on "Communication in a Mass-Technological Society." This research was supported

by grants from the University of the Open Road.]

“The necessity of imposing form of some sort has

continually led to the danger of imposing what is

essentially a false and artificial form. Once the

process of categorizing ideas is begun, it is likely

to become an end in itself and to give rise to the

subject a symmetry that is entirely false.”

--Samuel H. Monk, The Sublime.1

My research into the mass and technological characteristics of contemporary

society as they affect both theory and practice of human communication, led to

many different but integrally related fields of experience, including art, science,

politics, philosophy, technology and business. Frequently, a somewhat bothersome

problem seemed to pop up momentarily and then disappear. The problem occurred

in many variations in many fields; however, the seemingly diverse fields did not

address the variations as a common problem. Each field was content to chase each

instance of the problem independently, so it seemed.

For a variety of reasons, all working together, I call the class of elusive

problems the synecdochic fallacy, a collective name which is both fitting and

useful.2

In brief, the purpose of this paper is to identify the synecdochic fallacy as an

option for analyzing and generating communication in a mass-technological society.

This purpose is attempted through three means: first, by explaining what it is;

second, by offering historical warrant for its uses and third, by exploring several

examples derived from contemporary society.

The Synecdochic Fallacy: What It Is

A fallacy is a deceptive, misleading, erroneous, or false notion, belief, idea, or

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

statement. 3 A flawed conception is fallacious if it contains any of these. Fallacies

and flawed conceptions are only significant if they make a difference. If a particular

flawed conception has little or no consequence, it has little or no significance and

can be ignored. If a particular conception is flawed and it has much consequence, it

can still be ignored, but perhaps it should not be ignored. If a number of different

problems seem to share a similar flaw, there probably is a common fallacy as a

cause.4

Traditionally, the synecdoche is a figure of speech. Generally, it is a linguistic

device where a word representing a part of something is used to call forth an image

of the whole, as in the expressions, "all hands on deck" and "head count." In the

first expression "hands” represents "persons" as does "head" in the second

expression. The synecdoche also includes expressions where a whole is used to

represent a part, species for genus, genus for species, cause for effect, effect for

cause, container for thing contained, vice versa, and several other variations.

Though synecdoche frequently refers to a class of figures of speech, the term also

applies to matters of thought that see expression linguistically.5

Logically speaking, a synecdochic fallacy is a deceptive, misleading,

erroneous, or false notion, belief, idea, or statement where a part is substituted for a

whole, a whole for a part, cause for effect, effect for cause, and so on. Furthermore,

any particular instance of this fallacy and any conception flawed on account of this

fallacy is only significant if it is consequential.

Rhetorical-Historical Warrant

Neither the concept of the synecdochic fallacy nor its name is new. The

concept of the synecdoche appears twice in Book II of Aristotle’s Rhetoric under

lines of argument. 6 To Aristotle, one legitimate line of argument is treating

separately the parts of a subject. 7 Also, to Aristotle, one sham argument is asserting

that what is true of the parts is true of the whole, and vice versa.8 Though neither of

these communicative options open to rhetors is labeled as synecdoches, both

demonstrate the synecdoche at work, with Aristotle's sham argument demonstrating

the principle of the synecdochic fallacy.9

In Roman pedagogical frameworks of communicative options, many of what

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

Aristotle calls lines of arguments became codified as recurring patterns of linguistic

expression, that is, as figures of speech. As a figure, the synecdoche is discussed in

the Rhetorica ad Herennium and Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria.10 In addition to the

whole for part (and part for whole) substitution, the author ad Herennium includes

under synecdoche the linguistic substitution of singular for plural to which Quintilian

adds a temporal class of antecedent-consequent (cause-effect) substitutions.11

Though these authors use both the concept and the name of the synecdoche, they do

not explicitly link the figure to a line of argument. Nor do they develop the

synecdoche as a potential fallacy.

In contemporary history, the synecdoche has been revived akin to a line of

argument in the rhetorical scheme of Kenneth Burke.12 In Burke's contemporary

synthesis of the history of communicative options, the synecdoche is both a codified

linguistic expression (a figure of speech) and a line of argument. And though he

specifically names the synecdochic fallacy as a fallacy only once, the concept is a

major one in Burke's thought.

For Burke, the synecdoche figure includes uses of language where a part is

used to represent the whole, where the whole is used to represent a part, container

for thing contained, cause for effect, effect for cause, and the like.13 Yet, Burke

believes that it is no mere stylistic ornament as the Roman teachers might have us

believe. The more he studies language and the uses of language in the drama of

human relations, says Burke, “the more I become convinced that this is the 'basic'

figure of speech, and that it occurs in many modes besides that of the formal

trope.” 14

Further study of the synecdoche as a basic figure is demonstrated in Burke’s

Grammar of Motives. There, he discusses "Four Master Tropes" (metaphor,

metonymy, synecdoche, and irony) as the four basic attributes of human

conceptualization and expression. 15 For Burke, synecdoche is a basic process of

representation.

Sensory perception is, of course, synecdochic in that the senses

abstract certain qualities from some bundles of electro-chemical

activities we call say, a tree, and these qualities (such as size, shape,

color, texture, weight, etc.) can be said "truly to represent" a tree.

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

Similarly, artistic representation is synecdochic, in that certain relations

within the medium "stand for" corresponding relations outside it. There

is also a sense in which the well-formed work of art is internally

synecdochic, as the beginning of a drama contains its close or the close

sums up the beginning, the parts all thus being consubstantially

related.16

In this larger sense, the synecdoche as the process of representation (a mental

process through which thought, expression, and communication take place) is at

once useful as a codified linguistic expression (a figure as stylistic expression) and

useful as a mode of thought for generating ideas (a topic as a line of argument).

Burke expressly refers to the synecdochic fallacy only once, though he

expands upon the principal throughout much of his writing. In an essay he calls a

rhetorical defense of rhetoric, Burke states his thesis invoking the synecdochic

fallacy, "the ideal of a purely 'neutral' vocabulary, free of emotional weightings,

attempts to make a totality out of a fragment, 'till that which suits a part infects the

whole.’”17 In further developing a refutation to the sham distinction between

scientific and artistic expression and thought (that is, between "the sciences" and

"the humanities"), Burke comments, "Only by a kind of ‘synecdochic fallacy,'

mistaking a part for a whole, can this opposition appear to exist."18 Beyond this one

instance, I know of no other overt namings of the synecdochic fallacy, It does

however appear through other names.

The synecdochic fallacy is implied in Burke's discussion of his “Four Master

Tropes," the last appendix to A Grammar of Motives. The entire book is devoted

to the development and elaboration of a holistic, non-reductive, non-fragmentary

analytic-synthetic framework. In the book, Burke develops at length his oft

misunderstood pentad of terms for discussing human motive and action. After

presenting and illustrating the pentad (act, agent, scene, agency, purpose) and their

various ratios as terms (a grammar) for clarifying sources of ambiguity (motives),

Burke emphatically notes,

A terminology of conceptual analysis, if it is not to lead to misrepresentation,

must be constructed in conformity with a representative anecdote–whereas

anecdotes “scientifically” selected for reductive purposes are not representative.

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

19

(Burke’s emphasis.)

This statement represents for Burke a purpose for his Grammar--to provide a set of

terms for addressing problems of misrepresentation. 20 Though he does not state the

synecdochic fallacy by name, Burke strongly implies it. If, as he states, the

synecdoche as one of his four master tropes is the basic process of representation,

the synecdochic fallacy is another name for misrepresentation. Specifically, using

Burke's framework, misrepresentation (the synecdochic fallacy) is the use of

language to deceive with societally undesirable consequences wherever any

conception is based upon a misrepresentative substitution of part for whole, whole

for part, species for genus, genus for species, cause for effect, effect for cause, thing

contained for the container, and the like.21

Thus, the synecdochic fallacy is new neither in concept nor by name. It exists

conceptually in the lines of argument of Aristotle. The synecdoche occurs as a figure

of speech in Roman pedagogical rhetorics. And the synecdochic fallacy exists in

concept and by name as a representative mode of thought (that is, as a figure and as

a line of reasoning) in Burke’s writing, though Burke uses the name itself only once.

The remainder of the paper explores several examples of the synecdochic

fallacy derived from contemporary society. A rhetorical purpose for the examples is

to open up for analysis potentially harmful misrepresentations.

Examples

The following examples have been selected to illustrate the synecdochic

fallacy in a wide variety of instances. Some pertain to education, some to business,

some to science, some to politics; some pertain to communication in interpersonal

relations, some to problem solving, some to oratory, some to academic and

professional dialogue, some to mass communication, and some to societal

communication.

Example # 1: During spring term 1980, a student of public speaking offered a

persuasive speech on the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics to be held in

Moscow. The boycott came into public discussion as a result of two news items: (1)

the report of Russian troops sent into Afghanistan and (2) the report of a U.S. option

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

to retaliate by the Olympic boycott, among other options. When the student

addressed the boycott without referring to the Aghanistan situation, I invoked the

synecdochic fallacy. The student had entered into a public discussion and had

evaluated a proposed solution (the boycott) to a perceived problem (the invasion of

Afghanistan) without addressing the relationship of the solution to the problem. In

terms of the synecdochic fallacy, she took a part of an issue out of its container and

tried to make it stand by itself. In this particular case, the part (thing contained) was

very fluid and spilled onto the floor.

Example # 2: On July 6, 1981, economist Lewis Lehrman appeared on

NBC's Tomorrow show. At one instant, host Tom Snyder reiterated a popular idea,

government is the largest cause of inflation. Lehrman, appearing as an authority

figure on national TV, took the idea one step further and responded, "Government is

the only cause of inflation." The audience responded with enthusiastic applause.

Insofar as there was no mention of private businesses who receive government

contracts, insofar as there was no mention of laborers organizing to get higher pay,

and insofar as there was no mention of any other factor that might contribute to the

vicious cycle called inflation, one cause out of many was portrayed as the only

cause. It is therefore an instance of a synecdochic fallacy that someone could argue

is consequential because it breeds divisiveness on the basis of deception. 22

Example # 3: In his essay on “The Question Concerning Technology,”

Martin Heidegger invokes a particular synecdochic fallacy involving a cause-effect

substitution currently receiving much attention in many fields:

Modern physics is not experimental physics because it applies apparatus to

the questioning of nature. Rather the reverse is true. Because physics,

indeed already as pure theory, sets up nature to exhibit itself as a coherence

of forces calculable in advance, it therefore orders its experiments precisely

for the purpose of asking whether and how nature reports itself when set up

in this way. 23

Example # 4: In the area of art and aesthetic experience, Susanne K. Langer

pioneered research on a longstanding synecdochic fallacy that for some time has

obscured human perception and experience, Langer begins to chase an elusive

problem in Philosophy in a New Key.24 The chase continues though several works

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

including Feeling and Form and Problems of Art,25 but the basic synecdochic fallacy

can be heard (not seen) in the title of the pioneering Philosophy in a Hew Key. Her

argument is consistent with this statement:

Vision has been the primary sense for understanding the world around us;

sight has dominated human perception for thousands of years, as

civilization was transformed from an aural culture to a written culture.

Because of the dominance of sight over sound in Western Civilization, we

have been blinded and have been prevented from seeing, or rather from

hearing, other essential components of human experience.26

Similar instances to this fallacy based on the dominance of sight over other sense

perceptions can be found, if one listens.27

Example # 5: Tim LaHaye, pop author for the "Moral Majority,” has

popularized another part-for-whole synecdochic fallacy. In The Battle for the

Mind, LaHaye undertakes the task of exorcising humanism, which he claims, "is not

only the world's greatest evil but, until recently, the most deceptive of all religious

philosophies.” 28 If one were to argue that LaHaye's straw man conception of

humanism is based upon the taking of only a portion of what humanism has been

historically as opposed to the whole of humanism, one would be attempting to

thwart the effects of an up and coming synecdochic fallacy. W hat makes this

example interesting is that LaHaye's version of the fallacy is based upon yet another,

The Humanist Manifesto, which itself took only portions of humanism for the

whole. A tragedy here is that the two portions still do not make up a whole, as one

might get from understanding classical humanism and Renaissance humanism. In

this case the sum of the two parts equals less than the sum of the two parts, because

the two parts tend to diminish each other. 29

Example # 6: A similar part-for-whole instance occurs in M artin Heidegger's

"Question Concerning Technology." Speaking of technology as a force of much

dominance in the twentieth century Heidegger laments a semantic shift which

represents a much larger actual shift:

There was a time when it was not technology alone that bore the name

techne. Once that revealing that brings forth truth into the splendor of

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

radiant appearing also was called techne.

Once there was a time when the bringing-forth of the true into the

beautiful was called techne. And the poiesis of the fine arts also was

called techne.30

In this instance, typical of many others, only a portion of what was once a whole

range of meaning was given exclusive right to a name while other parts were lost,

both linguistically and actually.31

Example # 7: Actually, this last example is a class of instances. In relationships

between persons, role stereotyping frequently occurs. Wherever stereotyping

occurs, the synecdochic fallacy is in action. Thinking of a fellow human being only

in the capacity of a janitor is one instance. Seeing a man or a woman only--or almost

exclusively--as a potential sex partner is another. Hollywood typecasting offers

many other instances: Blacks portrayed as intimidated comic characters who sure

do dance a lot and have natural rhythm), Mexicans portrayed as wetbacks or as

fighters, troublemakers and all around ignorant agitators, and Whites portrayed as

good workers, owners of suburban homes, always wearing nice clothes, modern

cars, ans with fathers who always know best. All of these instances of stereotyping

can be considered as synecdochic where attributes of a part are taken to be

attributes of a whole. And insofar as they cause harm, they are consequential and

significant.

Conclusion

Through logical definition, historical warrant, and illustrative examples, I

have identified the synecdochic fallacy to be a fitting name for a useful concept. It

describes a variety of similar problems related to many aspects of communication in

our mass-technological society. Such a descriptive name (or handle) can enable

individuals with different sets of experiences to talk with each other about common

problems. As a problem, the synecdochic fallacy can belocated and named, as

shown above. As a concept, the synecdochic fallacy can generate analytical and

critical discussion in both public and private arenas. (That is to mean, as a rhetorical

topos, it can be used to generate ideas for persuasion and dissuasion.)

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

But, there are problems with the synecdochic fallacy which have not been

addressed here. And in not addressing them, that is, by painting only a partial

picture, so to speak, this paper commits a synecdochic fallacy. The examples

selected demonstrate a variety of instances of a seemingly common problem, yet,

these are only a few out of many. No discussion Has made of countless other

instances: the substitution of quantity over quality, the dominance of fact over

value,32 the mass mediated temporal dominance of the here and now found

pervasively in "the news," speaking of American Indians only in the past tense, the

biasing of history that yielded the twentieth century need for films like "Black

History: Lost, Strayed, or Stolen,” and the need for the aphorism, "Anonymous was

a woman."

Nor was any attempt made here to organize the various types of synecdochic

fallacies around topical schemes such as space, time, and mind; whole-for-part, part

for whole, cause for effect, effect for cause, container for thing contained, vice

versa, and so on.

Nor was any attempt made to organiee the synecdochic instances around

various types of communication, such as intrapersonal, interpersonal, dyadic, small

group, large group, private, public, mass, societal, inter-cultural, person to person,

person to machine, machine to person, machine to machine and so on.

Also, all of the examples tend to illustrate the part-for-whole synecdochic

fallacy--that is, where harmful consequences can be argued as resulting from

replacing a whole in a fragmentary way with a part (e.g., "Government is the only

cause of inflation."). None of the examples discussed above illustrate a

whole-for-part substitution where harm can be argued as resulting from replacing a

part in a synthesizing way with a whole, such as the use of the synecdochic fallacy

as an umbrella term (the whole) in substitution for a variety of similar but different

instances (the parts).

In defense of my own selectivity, I can only ask that my hearers agree that

our mass-technological society has tended to overemphasize analysis,

fragmentation, and divisiveness over synthesis, fusion, and harmony, and that at the

present point in time the latter (i.e., communication) is needed.

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

NOTES

1. Samuel H. M onk, The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in XVIII-

Century England (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1935), p.

4.

2. Neither the concept nor the name is original with this paper; I have merely

inherited them from much previous research. For some sources of both the concept

and the name, see the rhetorical-historical warrant section below, pp. 3-6.

3. See also Burke's A Rhetoric of Motives (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1950),

especially pp. 43-46. Compare this with I,A, Richards' exhortation, "Rhetoric, I

shall urge, should be a study of misunderstanding and its remedies." (The

Philosophy of Rhetoric (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. 3.)

4. See also Burke's A Rhetoric of Motives (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1950),

especially pp. 43-46. Compare this with I,A, Richards' exhortation, "Rhetoric, I

shall urge, should be a study of misunderstanding and its remedies." (The

Philosophy of Rhetoric (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. 3.)

5. A very lucid expression of this last idea is found in James J. Murphy, the concept

of topic and the concept of figures of speech and thought, presented to the Speech

Communication Association, San Antonio, Texas, November 1979.

6. Aristotle, Rhetoric, translated by W. Rhys Roberts (New York: Modern Library,

1954), pp. 149 and 156-57 (1399a6-9 and 1401a24-1401b3).

7. Ibid., p. 149.

8. Ibid., p. 156-57.

9. The concept is also to be found in the body of works discussed as “The Topics.”

10. [Cicero], De Ratione Dicendi (Rhetorica ad Herennium), with an

English translation by Harry Caplan (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard

University Press; Loeb Classical Library, 1954), pp. 340-43 (4.33.44-45);

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, vol. 3, with an English translation by

H.E., Butler (Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; Loeb

Classical Library, 1921), pp. 310ff. and 478-81 (8.6.19ff. and 9.3.58-61).

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

11. Ibid.

12. Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic

Action, 3rd ed. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press,

1973), pp.A 25-29, 60, 77-78, 102, 122, 138, 139, 278, 280, 288, and 450;

and A Grammar of Motives (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

Press, 1969; originally published in 1945), pp. 503, 507-511, and 516-17.

13. Burke, Philosophy, pp. 25-26 and Grammar, pp. 507-508.

14. Burke, Philosophy, p.26.

15. Burke, Grammar, pp. 503-517.

16. Ibid., p. 508.

17. Burke, Philosophy, p. 138. (The essay is titled, “Semantic and Poetic Meaning.”)

18. Ibid., p. 139.

19. Burke, Grammar, p. 510.

20. This point is made evident in Burke's introduction to his Grammar, pp. xv-xxiii.

See especially the photographic analogy (Road to Victory), on p. xvi.

21. See also Burke's A Rhetoric of Motives (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1950),

especially pp. 43-46. Compare this with I,A, Richards' exhortation, "Rhetoric, I

shall urge, should be a study of misunderstanding and its remedies." (The

Philosophy of Rhetoric (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. 3.)

22. Lehrman was identified as “Economist.” According to Who's Who in America,

1980-81 (vol. 2, p, 1990), Lehrman had been the chair of the executive committee of

the Rite Aid Corp, since 1977; was chair of the board of trustees and president of

the Lehrman Institute, and held several other positions of respect.

On the synecdochic fallacy of single causation, see note 4 above. On the

matter of the mass media as purveyors of synecdochic fallacies, see Justice William

0. Douglas' dissenting opinion, Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665 (1972), p. 721;

"TV's Battleground in El Salvador,” Newsweek (M arch 23, 1981), 17; I.F. Stone's

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

Weekly (a documentary film), (n.p.: Open End Cinema, 1973); Black History: Lost

Strayed, or Stolen (a documentary film), (New York: CBSTV, 1968). Evidence of

a temporal synecdochic fallacy in news media is implicit in Arthur Herzog's

"Newsthink,” in The B.S. Factor: The Theory and Technique of Faking It in

America (New York: Penguin Books, 1973), pp. 109-113.

23. Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, p. 21. For additional instances

concerning technology, see note 30 below, and James A. Kelso, “Science and the

Rhetoric of Reality," Central States Speech Journal 31 (Spring 1980), 28; Thomas

S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Second ed., enlarged, vol. 2 no. 2

International Encyclopedia of Unified Science (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1970); William Barrett, The Illusion of Technique: A Search for Meaning in

a Technological Civilization (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday,

1979), pp.165-66; and Kenneth Burke, Counter-Statement, second ed., (Berkeley

and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968; originally published in

1932), p, 31.

24. Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of

Reason, Rite, and Art (Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press,

1942.).

25.Susanne K. Langer, Feeling and Form (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons,

1953) and Problems of Art (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1957).

26. This is a composite synopsis synthesizing many ideas found in the works

of Alfred North Whitehead, Susanne K, Langer, Kenneth Burke, I,A, Richards,

H. Marshall McLuhan, and Waiter J. Ong, S.J. among other contemporary

thinkers.

27. For more on the matter of sound, see Don Ihde, Sense and Significance

(distributed by Humanities Press, New York for Duquesne University Press,

Pittsburgh, 1973) and Listening and Voice: A Phenomenology of Sound (Athens,

Ohio: Ohio University Press). Waiter J. Ong’s The Presence of the Word, Rhetoric,

Romance, and Technology, and Interfaces of the Word also have much to say on

sound, understanding and civilization.

28. Tim LaHaye, The Battle for the M ind (Old Tappan, New Jersey, Flemming H.

Revell, 1980), p. 57.

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

29. For related material, see Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives, pp. 332-333,

The Rhetoric of Religion: Studies in Logology (Berkeley and Los Angeles,

University of California Press, 1970; originally published in 1960), and Language as

Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature,:and Method, third printing (Berkeley

and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973), pp. 406-407.

30. Heidegger, Question Concerning Technology., pp. 12-13.

31. Many other contemporary thinkers argue the same point about reclaiming a fuller

meaning for techne. Ihde’s Technics and Praxis, for example, is a renaming of

theory and practice which seeks to restore techne as more than mere doing without

great forethought. For other instances relating to technology, see Don Ihde,

Technics and Praxis (Boston: D. Reidel, 1979), pp. Xix, 3, 4, 11, 83, and 85;

Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, pp. 28 and 34: Barrett, The

Illusion of Technique, p. 183; and Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies

in the Ideology of Advanced industrial Society (Boston: Beacon Press, 1964), pp.

238-39.

A linguistic truncation similar to what happened with techne happened with

discrimination. W hereas the word once meant differentiation and distinction,

repeated usage in our mass-mediated society linked the word to matters of race and

civil rights until the word took on a more and more limited meaning. At one

moment, the meaning became so restricted that the biasing of circumstances against

a white male could no longer be called discrimination, but rather an inferior

sounding re-VERSE discrimination.

32. See, for instances, Wayne C. Booth, Modem Dogma and the Rhetoric of Ascent

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), pp, 13-21, 121-25, and 207-11; J.

Bronowski, Science and Human Values (New York: Harper & Row; Harper

Torchbooks, 1965), pp, 6, 27, 56, 65, and 70-71; Kenneth Burke, "Terministic

Screens," in Language as Symbolic Action, pp.:44-62, especially pp. 44-46;

Barry.Commoner, "Scientific Statesmanship," in Representative

American Speeches, 1962-63, edited by Lester Thonssen (The Reference Shelf,

vol. 35, no. 4), pp. 68-81; W alter R. Fisher, "Toward a Logic of Good Reasons,”

Quarterly Journal of Speech 64 (December 1978), 376-84; and Herbert Marcuse

One-Dimensional Man, pp. 133, 139-40, 142, 146ff., 167, and 184.

_____________________________________________________________________

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

October 13, 2004

This document was evidently scanned on September 19, 2002. It looks reasonably

intact. It looks like it has been proofread; however, additional proofreading is planned.

Feel free to read and cite; however, please do not quote without having me verify

specific quotations. Paraphrases should be fine.

Please double check any references from the endnotes. Frequently scanning

introduces errors in endnotes. Please e-mail me with possible corrections or questions.

Thanks.

Weinstock, Stephen M. The Synechdochic Fallacy in a Mass-Technological Society.” Speech Communication

Association, November 1981, Anaheim, California. WebDoc version 0.00 posted October 13, 2004.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Cognitive Semiotic Approach To Sound SymbolismDocumento51 pagineA Cognitive Semiotic Approach To Sound SymbolismJacek TlagaNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Teacher's Support Book 5 Iii: Rod FlickerDocumento227 pagineAdvanced Teacher's Support Book 5 Iii: Rod FlickerVukan Jokic100% (1)

- Asa Berger - SemioticsDocumento42 pagineAsa Berger - SemioticsJhawley2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Turner, Victor - Dramas Fields and MetaphorsDocumento39 pagineTurner, Victor - Dramas Fields and MetaphorsJoaquin Solano100% (3)

- Conceptualization of IdeologyDocumento9 pagineConceptualization of IdeologyHeythem Fraj100% (1)

- Bilingual ChildrenDocumento0 pagineBilingual ChildrenbernardparNessuna valutazione finora

- A Cognitive-Semiotic Construal of MetaphorDocumento25 pagineA Cognitive-Semiotic Construal of MetaphorPreservacion y conservacion documentalNessuna valutazione finora

- Auditing The Art and Science of Assurance Engagements Canadian Twelfth Edition Canadian 12th Edition Arens Test BankDocumento10 pagineAuditing The Art and Science of Assurance Engagements Canadian Twelfth Edition Canadian 12th Edition Arens Test BanktestbanklooNessuna valutazione finora

- A Spirituality of TensionsDocumento70 pagineA Spirituality of TensionsRolphy PintoNessuna valutazione finora

- Institutional EconomicsDocumento12 pagineInstitutional Economicsicha100% (1)

- Ways of Seeing, Ways of Speaking: The Integration of Rhetoric and Vision in Constructing the RealDa EverandWays of Seeing, Ways of Speaking: The Integration of Rhetoric and Vision in Constructing the RealNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophical Approaches To Communication - Claude Mangion PDFDocumento338 paginePhilosophical Approaches To Communication - Claude Mangion PDFMaria Jessica Ola SugiartoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1 High Quality Assessment in RetrospectDocumento30 pagineLesson 1 High Quality Assessment in RetrospectCatherine Tan88% (8)

- English 10 - F2F 6Documento5 pagineEnglish 10 - F2F 6Daniela DaculanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kenneth Burke - Archetype and EntelechyDocumento18 pagineKenneth Burke - Archetype and Entelechyakrobata1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Burke - About The PentadDocumento7 pagineBurke - About The PentadFiktivni FikusNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive - Linguistics and Poetics of TranslationDocumento109 pagineCognitive - Linguistics and Poetics of TranslationBlanca Noress100% (3)

- Referral System in IndiaDocumento24 pagineReferral System in IndiaKailash Nagar100% (1)

- Herman DavidDocumento22 pagineHerman Davidshe_buzz100% (1)

- Metaphorizing Dialogue To Enact A Flow Culture: Transcending Divisiveness by Systematic Embodiment of Metaphor in DiscourseDocumento22 pagineMetaphorizing Dialogue To Enact A Flow Culture: Transcending Divisiveness by Systematic Embodiment of Metaphor in DiscourseAnthony JudgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphor: Theories: Scientists LogiciansDocumento6 pagineMetaphor: Theories: Scientists LogiciansUrsu TinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphors - A Creative Design Approach or TheoryDocumento11 pagineMetaphors - A Creative Design Approach or TheoryPriscilia ElisabethNessuna valutazione finora

- The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and ReasonDa EverandThe Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and ReasonValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Chapter 5 Literature and IdeologyDocumento33 pagineChapter 5 Literature and IdeologyKristijan SirnikNessuna valutazione finora

- Deely. Basics of SemioticsDocumento137 pagineDeely. Basics of SemioticsDaniel Montanez100% (1)

- My Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogDocumento3 pagineMy Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogK wongNessuna valutazione finora

- 98-134. 3. Project For A Discursive CriticismDocumento38 pagine98-134. 3. Project For A Discursive CriticismBaha ZaferNessuna valutazione finora

- 225 King On Semiotic Determinism and The Visual Sign PDFDocumento10 pagine225 King On Semiotic Determinism and The Visual Sign PDFJavier LuisNessuna valutazione finora

- Parret - 2Documento5 pagineParret - 2AlexandreWesleyTrindadeNessuna valutazione finora

- MeyerChristian2016Face To FaceCommunicationDocumento10 pagineMeyerChristian2016Face To FaceCommunicationKudakwashe TozivepiNessuna valutazione finora

- How Do We Mean? A Constructivist Sketch of SemanticsDocumento8 pagineHow Do We Mean? A Constructivist Sketch of SemanticsjuanjulianjimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Zooming On IconicityDocumento18 pagineZooming On IconicityJuan MolinayVediaNessuna valutazione finora

- C/Users/Andrew/Documents/Articles/Semiotic AnalysisDocumento42 pagineC/Users/Andrew/Documents/Articles/Semiotic AnalysisAndrew OlsenNessuna valutazione finora

- Andreichuk Cultural SemioticsDocumento5 pagineAndreichuk Cultural SemioticsakunjinNessuna valutazione finora

- Embodiment in The Semiotic Matrix Introd PDFDocumento12 pagineEmbodiment in The Semiotic Matrix Introd PDFkikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ehses, H. Representing Macbeth - A Case Study in Visual RhetoricDocumento11 pagineEhses, H. Representing Macbeth - A Case Study in Visual RhetoricRicardo Cunha LimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring Analogy: Introduction Religious Language Is Growing Respectable Again. It Had FallenDocumento13 pagineExploring Analogy: Introduction Religious Language Is Growing Respectable Again. It Had FallenHERACLITONessuna valutazione finora

- Dialogue at The BoundaryDocumento21 pagineDialogue at The BoundaryTheo NiessenNessuna valutazione finora

- Turner - BLEND. - Аннотации докладов -Documento58 pagineTurner - BLEND. - Аннотации докладов -Дарья БарашеваNessuna valutazione finora

- Semiolo y and Architecture: Charles JencksDocumento21 pagineSemiolo y and Architecture: Charles JenckssssNessuna valutazione finora

- Malik Fixing MeaningDocumento14 pagineMalik Fixing MeaningMorganElderNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.2 Dialogism and DialecticDocumento3 pagine1.2 Dialogism and DialecticSebastian Montenegro MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Michel Foucaults Theory of Rhetoric As EpistemicDocumento20 pagineMichel Foucaults Theory of Rhetoric As EpistemicLubna MariumNessuna valutazione finora

- Barthes: Intro, Signifier and Signified, Denotation and ConnotationDocumento5 pagineBarthes: Intro, Signifier and Signified, Denotation and ConnotationDungarmaa ErdenebayarNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Talk: Directions From Bernstein's SociologyDocumento6 pagineUnderstanding Talk: Directions From Bernstein's SociologyalepedragosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphor Aristotle Tragedy Term: Catharsis, The Purification or Purgation of The Emotions (EspeciallyDocumento6 pagineMetaphor Aristotle Tragedy Term: Catharsis, The Purification or Purgation of The Emotions (Especiallyshila yohannanNessuna valutazione finora

- English ProjectDocumento22 pagineEnglish ProjectaatishNessuna valutazione finora

- 0 19 442160 0 A With Cover Page v2Documento27 pagine0 19 442160 0 A With Cover Page v2Ahmad ikhwan MataliNessuna valutazione finora

- Discursive Constructions On Spanish Languages: Towards Overcoming The Conflict FrameworkDocumento22 pagineDiscursive Constructions On Spanish Languages: Towards Overcoming The Conflict FrameworkEsperanza Morales LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhetorical CitizenshipDocumento11 pagineRhetorical CitizenshipLauren Cecilia Holiday Buys100% (1)

- Wino Grad 1987Documento12 pagineWino Grad 1987leofn3-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Petra Aczel. Visionary RhetoricDocumento11 paginePetra Aczel. Visionary RhetoricAnonymous NPbGa8U4100% (1)

- INGOLD, T. Resonators Uncased Mundane Objects or Bundles of AffectDocumento5 pagineINGOLD, T. Resonators Uncased Mundane Objects or Bundles of AffectlarabritoribeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Prcis of Relevance Communication and CognitionDocumento14 paginePrcis of Relevance Communication and CognitionЕлена РогожинаNessuna valutazione finora

- Some Elements of StructuralismDocumento8 pagineSome Elements of StructuralismDhimitri BibolliNessuna valutazione finora

- Hearing, Seeing and Acting: A Peircean-Semiotic Perspective, On Samuel Beckett's Acts Without Words IDocumento24 pagineHearing, Seeing and Acting: A Peircean-Semiotic Perspective, On Samuel Beckett's Acts Without Words Imuntadher alaskaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Discourse Analysis Is A Research Method For Studying Written or SpokenDocumento23 pagineDiscourse Analysis Is A Research Method For Studying Written or SpokenZeeshan ch 'Hadi'Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Semiotics of Aspects of English and Yoruba Proverbs Adeyemi DARAMOLADocumento10 pagineA Semiotics of Aspects of English and Yoruba Proverbs Adeyemi DARAMOLACaetano RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Difference Between Semiotics and SemDocumento17 pagineThe Difference Between Semiotics and SemNora Natalia LerenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Post StructuralismDocumento26 paginePost StructuralismnatitvzandtNessuna valutazione finora

- Postmedia Performance: Sarah Bay-ChengDocumento5 paginePostmedia Performance: Sarah Bay-ChengPietro GrandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hang 2020Documento4 pagineHang 2020Honglin QiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociolingustics 2011 LibreDocumento11 pagineSociolingustics 2011 LibreEmilia MissioneNessuna valutazione finora

- ImreAttila-MetaphorsinCognitiveLinguistics 2010Documento12 pagineImreAttila-MetaphorsinCognitiveLinguistics 2010Annisa FadhilahNessuna valutazione finora

- Art As LanguageDocumento13 pagineArt As LanguageZawar HashmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Grossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997Documento40 pagineGrossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997jessenigNessuna valutazione finora

- Why the West Is Not the Best : 10 Superiority MythsDa EverandWhy the West Is Not the Best : 10 Superiority MythsNessuna valutazione finora

- Proceedings of The Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of A Biological CharacterDocumento9 pagineProceedings of The Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of A Biological CharactergogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento6 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento28 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento3 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento8 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento23 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- The Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access ToDocumento9 pagineThe Royal Society Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve, and Extend Access TogogunusedNessuna valutazione finora

- View of The SelfDocumento10 pagineView of The SelfCherry ArangconNessuna valutazione finora

- SF2 LACT 3 Teacher NanDocumento5 pagineSF2 LACT 3 Teacher NanLignerrac Anipal UtadNessuna valutazione finora

- Format. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainDocumento10 pagineFormat. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Kristen Roberts: 4845 Hidden Shore Drive Kalamazoo, MI 49048 Phone: (269) 377-3386 EmailDocumento2 pagineKristen Roberts: 4845 Hidden Shore Drive Kalamazoo, MI 49048 Phone: (269) 377-3386 Emailapi-312483616Nessuna valutazione finora

- Create Your Own Culture Group ProjectDocumento1 paginaCreate Your Own Culture Group Projectapi-286746886Nessuna valutazione finora

- P3 Business Analysis 2015 PDFDocumento7 pagineP3 Business Analysis 2015 PDFDaniel B Boy NkrumahNessuna valutazione finora

- Shailendra Kaushik27@Documento3 pagineShailendra Kaushik27@naveen sharma 280890Nessuna valutazione finora

- 21 Century Success Skills: PrecisionDocumento13 pagine21 Century Success Skills: PrecisionJoey BragatNessuna valutazione finora

- Political DoctrinesDocumento7 paginePolitical DoctrinesJohn Allauigan MarayagNessuna valutazione finora

- Problems and Prospects of Guidance and Counselling Services in Secondary Schools in Jigawa StateDocumento10 pagineProblems and Prospects of Guidance and Counselling Services in Secondary Schools in Jigawa StateRosy BlinkNessuna valutazione finora

- Themes Analysis in A NutshellDocumento2 pagineThemes Analysis in A Nutshellapi-116304916Nessuna valutazione finora

- BATALLA, JHENNIEL - STS-Module 7Documento5 pagineBATALLA, JHENNIEL - STS-Module 7Jhenniel BatallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kelsey Klein ResumeDocumento1 paginaKelsey Klein Resumeapi-354618527Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group 1 BARC CaseDocumento14 pagineGroup 1 BARC CaseAmbrish ChaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Candidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To QuestionsDocumento2 pagineCandidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To Questionsmbrnadine belgica0% (1)

- Business Communication Group Proposal Group 3: Aroma Resort: Handle The Scandal With Youtuber Khoa PugDocumento8 pagineBusiness Communication Group Proposal Group 3: Aroma Resort: Handle The Scandal With Youtuber Khoa PugHằng ThuNessuna valutazione finora

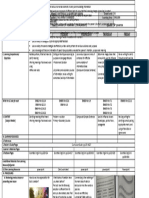

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachDocumento1 paginaGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachIrene Tayone GuangcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Causal EssayDocumento8 pagineCausal Essayapi-437456411Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1402-Article Text-5255-2-10-20180626Documento5 pagine1402-Article Text-5255-2-10-20180626Rezki HermansyahNessuna valutazione finora

- Long Exam: 1671, MBC Bldg. Alvarez ST., Sta. Cruz, ManilaDocumento2 pagineLong Exam: 1671, MBC Bldg. Alvarez ST., Sta. Cruz, ManilakhatedeleonNessuna valutazione finora

- Simile and MetaphorDocumento2 pagineSimile and Metaphorapi-464699991Nessuna valutazione finora