Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Febrile Seizures Evaluation and Treatment

Caricato da

Azizah F AndyraCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Febrile Seizures Evaluation and Treatment

Caricato da

Azizah F AndyraCopyright:

Formati disponibili

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/318305926

Febrile Seizures: Evaluation and Treatment

Article in Journal of clinical outcomes management: JCOM · July 2017

CITATIONS READS

0 184

2 authors:

Michael Scott Perry Anup D Patel

Cook Children's Health Care System Nationwide Children's Hospital

45 PUBLICATIONS 323 CITATIONS 48 PUBLICATIONS 446 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Coregistration of multimodal imaging in pediatric epilepsy surgery View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Michael Scott Perry on 22 July 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Case-based review

Febrile Seizures: Evaluation and Treatment

Anup D. Patel, MD, and M. Scott Perry, MD

Abstract

• Objective: To review the current understanding and than once during a febrile illness, or lasts more than 10

management of febrile seizures. minutes. Febrile status epilepticus, a subtype of complex

• Methods: Review of the literature. febrile seizures, represents about 25% of all episodes of

• Results: Febrile seizures are a common manifestation childhood status epilepticus. They account for more than

in early childhood and very often a benign occur- two-thirds of cases during the first 2 years of life.

rence. For simple febrile seizures, minimal evaluation The risk of reoccurrence after presenting with one

is necessary and treatment typically not warranted febrile seizure is approximately 30%, with the risk being

beyond reassurance and education of caregivers. For 60% after 2 febrile seizures and 90% after 3 [4–6]. Some

complex febrile seizures, additional evaluation in rare families have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

cases may suggest an underlying seizure tendency, with polygenic inheritance suspected for the majority of

though most follow a typical benign course of febrile patients presenting with febrile seizures.

seizures. In some cases, as-needed benzodiazepines Multiple chromosomes have been postulated to be

used for prolonged or recurrent febrile seizures may associated with genetic susceptibility for febrile seizures,

be of value. There are well described epilepsy syn- with siblings having a 25% increased risk and high con-

dromes for which febrile seizures may be the initial cordance noted in monozygotic twins [7]. The patho-

manifestation and it is paramount that providers rec- physiology for febrile seizures has been associated with a

ognize the signs and symptoms of these syndromes genetic risk associated with the rate of temperature rise

in order to appropriately counsel families and initiate with animal studies suggesting temperature regulation

treatment or referral when warranted. of c-aminobutyric acid (GABA) a receptors [2]. Other

• Conclusion: Providers caring for pediatric patients studies propose a link between genetic and environmental

should be aware of the clinical considerations in man- factors resulting in an inflammatory process which influ-

aging patients with febrile seizures. ences neuronal excitement predisposing one to a febrile

seizure [8].

Key words: febrile seizure; Dravat syndrome; GEFS+; PCDH19; Debate exists between the relation of febrile seizures

FIRES; complex febrile seizure. and childhood vaccinations. Seizures are rare follow-

ing administration of childhood vaccines. Most seizures

A

febrile seizure is defined as a seizure in associa- following administration of vaccines are simple febrile

tion with a febrile illness in the absence of a cen- seizures [9]. Febrile seizures associated with vaccines are

tral nervous system infection or acute electrolyte more associated with underlying epilepsy. In a study of

imbalance in children older than 1 month of age without patients with vaccine-related encephalopathy and febrile

prior afebrile seizures [1]. The mechanism by which status epilepticus, the majority of patients were found to

fever provokes a febrile seizure is unclear [2]. Febrile sei- have Dravet syndrome; it was determined that the vaccine

zures are the most common type of childhood seizures, may have triggered an earlier onset of the presentation for

affecting 2% to 5% of children [1]. The age of onset is Dravet in those predestined to develop this disease but did

between 6 months and 5 years [3]; peak incidence occurs not adversely impact ultimate outcome [10].

at about 18 months of age. Simple febrile seizures are

the most common type of febrile seizure. By definition,

they are generalized, last less than 10 minutes and only From the Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH

occur once in a 24-hour time-period. A complex febrile (Dr. Patel) and Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth,

seizure is one with focal onset or one that occurs more TX (Dr. Perry).

www.jcomjournal.com Vol. 24, No. 7 July 2017 JCOM 325

Febrile Seizures

In this article, we review simple and complex febrile Daily preventative therapy with an anti-epilepsy medi-

seizures with a focus on clinical management. Epilepsy syn- cation is not necessary [3,11]. A review of several treat-

dromes associated with febrile seizures are also discussed. ment studies shows that some anti-epileptic medica-

Cases are provided to highlight important clinical con- tions are effective in preventing recurrent simple febrile

siderations. seizures. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of

phenobarbital, primidone, and valproic acid in prevent-

Case 1: Simple Febrile Seizure ing the recurrence of simple febrile seizures; however,

A 9-month-old infant and his mother present the side effects of each medication outweighed the ben-

to the pediatrician. The mother notes that the efit [3]. Carbamazepine and phenytoin have not been

infant had an event of concern. She notes the infant had shown to be effective in preventing recurrent febrile

stiffness in all 4 extremities followed by jerking that last- seizures [3].

ed 30 to 60 seconds. The infant was not responsive dur- For anxious caregivers with children having recurrent

ing the event. He was sleepy afterward, but returned to febrile seizures, a daily medication or treating with an

normal soon after the event ended. After, she noted that abortive seizure medication at the time of a febrile illness

the infant felt warm and she checked his temperature. He can be considered [3,5,6,15]. Treating with an abortive

had a fever of 101°F. The infant has normal development medication may mask signs and symptoms of meningitis

and no other medical problems. making evaluation more challenging [16]. Evidence does

not support that using antipyretic medications such as

acetaminophen or ibuprofen will reduce the recurrence

• What are management considerations for of febrile seizures. The seizure usually is the first noticed

simple febrile seizure? symptom due to the rise of temperature being the cause

of the febrile seizure in an otherwise well child prior to

the seizure [11,17]. Damage to the brain and associated

A simple febrile seizure is the most common type of structures is not found with patients presenting with

febrile seizure. They are generalized, lasting less than 10 simple febrile seizures [5,6]. Education on all of these

minutes and only occur once in a 24-hour period. There principles is strongly recommended for caregiver reas-

is no increased risk of developing epilepsy or developmen- surance.

tal delay for patients after the first simple febrile seizures

when compared to other children [5,6]. The diagnosis Case 2: Complex Febrile Seizures

is based on history provided and a physical examination A 1-year-old child presents to the emergency

including evaluation of body temperature [11,12]. department. Mother was with the child and she

No routine laboratory tests are needed as a result of a noticed stiffness followed by jerking of the left arm and

simple febrile seizure unless obtained to assist in identify- leg, which quickly became noted in both arms and legs.

ing the fever source [3,11]. Routine EEG testing is not The episode appeared to last for 15 minutes before EMS

recommended for these patients [3,11]. Routine imaging arrived to the house. A medication was given to the child

of the brain is also not needed [3,11]. Only if a patient by EMS that stopped the event. EMS noted the child had

has signs of meningitis should a lumbar puncture be a temperature of 101.5°F. The child was previously healthy

performed [11]. The American Academy of Pediatrics and has had normal development thus far.

states that a lumbar puncture is strongly considered for

those younger than 12 months if they present with their

first complex febrile seizure as signs of meningitis may be • What is the epidemiology of complex febrile

absent in young children. For infants 6 to 12 months of seizure?

age, a lumbar puncture can be considered when immuni-

zation status is deficient or unknown [13,14]. Also, a lum-

bar puncture is an option for children who are pretreated A complex febrile seizure is one with focal onset, or one

with antibiotics [11]. For patients younger than 6 months, that occurs more than once during a febrile illness or lasts

data is lacking on the percentage of patients with bacterial more than 10 minutes. They are less common, represent-

meningitis following a simple febrile seizure. ing only 20% to 30% of all febrile seizures [18–20]. In

326 JCOM July 2017 Vol. 24, No. 7 www.jcomjournal.com

Case-based review

The National Collaborative Perinatal Project (NCPP), of cases of MTS or complex partial seizures are associated

1706 children with febrile seizures were identified from with prior febrile seizures [20,22].

54,000 and were followed from birth until 7 years of age.

The initial febrile seizure was defined as complex in about

28%. For all febrile seizures, focal features were present

in 4%, prolonged duration (> 10 minutes) in 7.6%, and • What is the risk of intracranial pathology in

recurrent episodes within 24 hours in 16.2% [21]. Similar complex febrile seizure?

observations have been reported by Berg and Shinnar

[5,6]. Of 136 children who had recurrences, 41.2% had

one or more complex features and the strongest cor- Patients with complex febrile seizures usually seek medi-

relate of having recurrent complex febrile seizure was cal attention [27]. However, the risk of acute pathology

the number of recurrent seizures. They also found that necessitating treatment changes based on neuroimaging

children with complex recurrences had other recurrences was found to be very low and likely not necessary in the

that were not complex; however, complex features had a evaluation of complex febrile seizures during the acute

tendency to recur. Further, a strong association between presentation [27]. Imaging with a high-resolution brain

focal onset and prolonged duration was found [5,6]. MRI could be considered later on a routine basis for

Previous studies established a correlation between com- prolonged febrile seizures due to the possible association

plex attacks, particularly prolonged ones and young age between prolonged febrile seizures and mesial temporal

(age < 1 year) [5,6]. Additionally, children with seizures sclerosis [19,28,29].

with a relatively low fever (< 102°F) were slightly more Neuroimaging has provided evidence that hippo-

likely to have a complex febrile seizure as the initial epi- campal injury can occasionally occur during prolonged

sode [5,6]. and focal febrile seizures in infants who otherwise

Children with febrile seizures are already at 4- to appear normal. It has been speculated that a pre-existing

5-fold increased risk for subsequent unprovoked seizures. abnormality increases the propensity to focal prolonged

A history of febrile seizures has been found in 13% to seizures and further hippocampal damage. Hesdorffer

18% of children with new-onset epilepsy. In the NCPP and colleagues [30] found definite abnormalities on

study, the predictors identified for the development of MRI in 14.8% of children with complex febrile seizures

epilepsy following febrile seizures were an abnormal and 11.4 % of simple febrile seizures among 159 children

neurological and developmental status of the child with a first febrile seizure. However, MRI abnormalities

before the seizure, a history of afebrile seizures in a par- were related to a specific subtype of complex seizures:

ent or prior-born sibling, or complex features [21]. Ten focal and prolonged. The most common abnormalities

percent of children with 2 or more of the previously observed were subcortical focal hyperintensity, an abnor-

mentioned risk factors (including complex features) de- mal white matter signal, and focal cortical dysplasia.

veloped epilepsy and 13% of them had seizures without

fever [20,22]. Further, intractable epilepsy and neu-

rological impair-ment have been found to be more • What are important aspects of the clinical

common in children with prior prolonged febrile sei- evaluation?

zure, with no association to any specific seizure type

[18,23–25]. The association between febrile seizures

and mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) is a commonly The evaluation and management of the child with

debated topic. Retrospective studies have reported an complex febrile seizures is debated as well. The most

association between prolonged or atypical febrile sei- important part in the history and examination is to look

zures and intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. Epide- for the source of the fever and rule out the presence of a

miological studies fail to show a causal relationship CNS infection, since complex febrile seizures are much

between febrile seizures and temporal lobe epilepsy more frequently associated with meningitis than simple

[26]. This suggests that febrile seizures are a marker of febrile seizures [16]. The American Academy of Pediatrics

susceptibility to seizures and future epilepsy (in some recommended that a lumbar puncture be strongly consid-

cases) rather than a direct cause. It is clear that a minority ered in infants younger than 12 months after a first febrile

www.jcomjournal.com Vol. 24, No. 7 July 2017 JCOM 327

Febrile Seizures

seizure and should be considered in children between or third-generation anti-epilepsy medications in the treat-

12 and 18 months of age, since signs of meningitis may ment of recurrent of complex febrile seizures [3].

be absent in young children [13]. If the threshold for a It is unclear whether benefit is present to using inter-

lumbar puncture is low in infants with febrile seizures in mittent benzodiazepine doses prior or during a febrile

general, it should be even lower for children with com- illness for those prone for recurrent febrile seizures [33].

plex febrile episodes for all the factors mentioned above. Physicians may consider this option in patients with fre-

The guidelines developed in 1990 by the Royal College quent recurrent seizures, when caregivers can identify the

of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association con- fever before the seizure occurs.

cluded that indications for performing an lumbar puncture Overall, parental education of efficacy and side effect

were complex febrile seizure, signs of meningismus, or a profiles should be discussed in detail when considering

child who is unduly drowsy and irritable or systematically any treatment options for complex febrile seizures [34].

ill [21]. It is important to remember that the long-term prognosis

Obtaining an EEG within 24 hours of presentation in terms of developing epilepsy or neurological and cog-

may show generalized background slowing, which could nitive problems is not influenced by the use of antiepilep-

make identifying possible epileptiform abnormalities dif- tic medications for recurrent febrile seizures [17]. Even in

ficult [22]. Therefore, a routine sleep deprived EEG when the case of prolonged febrile seizures in otherwise neuro-

the child is back to baseline can be more useful in identi- developmentally normal children, antiepileptics have not

fying if epileptiform abnormalities are present. If epilepti- been shown to cause damage to the brain [19].

form abnormalities are present on a routine sleep deprived

EEG, this may suggest the patient is at higher risk for Febrile Status Epilepticus

developing future epilepsy and the febrile illness lowered Febrile status epilepticus is a subtype of complex febrile

the seizure threshold; however, it is unclear whether clini- seizures and is defined as a febrile seizure lasting greater

cal management would change as a result [31]. than 30 minutes. Overall, febrile status epilepticus

accounts for approximately 5% of all presentations of

febrile seizures [35]. It represents about 25% of all epi-

• What treatment options are available? sodes of childhood status epilepticus and more than two-

thirds of cases during the first 2 years of life. Literature

suggests that an increased risk for focal epilepsy exists

Complications with prolonged and/or recurrent seizures [36]. Children presenting with febrile status epilepticus

can occur. Treatments options can be stratified into 3 are more likely to have a family history of epilepsy and

possible categories: emergency rescue treatment for pro- a history of a previous neurological abnormality [22].

longed or a cluster of febrile seizures, intermittent treat- It is likely to reoccur if the first presentation was febrile

ment at the time of illness, and chronic use of medica- status epilepticus. However, increased risk for death or

tion. Treatment options for complex febrile seizures may developmental disability as a result of the seizure is not

include the use of a rescue seizure medication when the seen [37].

febrile seizure is prolonged. Rectal preparations of diaz- The prospective multicenter study of the consequences

epam gel can be effective in stopping an ongoing seizure of prolonged febrile seizures in childhood (FEBSTAT)

and can be provided for home use in patients with known has been conducted. The study reported that febrile status

recurrence of febrile status epilepticus [3]. For children epilepticus is usually focal (67% of episodes), occurs in very

and adolescents where a rectal administration is not ideal, young children (median age 1.3 years), and is frequently

intranasal versed can be utilized instead of rectal diaz- the first febrile seizure [22]. In this study, the median

epam. In addition, the use of an intermittent benzodiaz- duration of the seizure was about 68 minutes and 24%

epine at the onset of febrile illness can also be considered of children had an episode lasting more than 2 hours. In

a treatment option. Using oral diazepam at the time of 87% of the events, seizures did not stop spontaneously and

a febrile illness has been demonstrated in reducing the benzodiazepines were needed. Focal features observed

recurrence of febrile seizures [3]. Other studies have were eye and head deviation, staring, and impaired con-

shown similar results when using buccal midazolam [32]. sciousness prior to the seizure and an asymmetric convul-

No adequate studies have been performed using second- sion or Todd’s paresis.

328 JCOM July 2017 Vol. 24, No. 7 www.jcomjournal.com

Case-based review

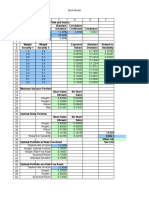

Table. Epilepsy Syndromes Frequently Associated with Seizures in the Setting of Fever

Dravet PCDH19-Associated

GEFS+ Syndrome Epilepsy HHE FIRES

Age at onset <1y <1y <1y <4y From childhood to

adulthood

Common Tonic-clonic, Hemiclonic, tonic- Focal seizures present- Hemiclonic pre- Focal seizures pre-

seizure types myoclonic, clonic, absence, ing in clusters, tonic, senting as status senting as status

absence, myoclonic, tonic, tonic-clonic epilepticus epilepticus

atonic, focal clonic

Status epilepticus Rare Common Rare Common Common

Family history Strong Rare Rare Rare Rare

Common None specific. Clobazam, valproate, No specific antiepileptic Benzodiazepines All antiepileptic

treatments Depends on fre- stiripentol. Avoid drugs known to be more 1st line. Multiple drugs can be tried;

quency of seizures. sodium-channel effective other antiepileptic often continuous

PRN benzodiaz- antiepileptic drugs. drugs can be infusions are needed.

epines common. used. Ketogenic diet

Prognosis Varies—most Moderate-severe Mild-moderate develop- Permanent hemi- Poor seizure control,

normal to mild developmental delays, mental delays. Remis- plegia in 80% developmental delays.

delays. Remission autism, ADHD. sion in 1/3 of patients. Mortality in 30%.

in many patients. Unlikely to remit.

Case 3: Epilepsy Syndromes Associated Dravet syndrome. Recognizing the early signs and symp-

with Febrile Seizures toms of these disorders, particularly the more severe phe-

A 1-year-old female presents for evaluation of notypes, is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and misleading

seizures that began at age 8 months. Seizures reassurance. Likewise, early recognition of many of these

are described as occurring in the setting of fever with syndromes may alter the treatment paradigm which in

bilateral symmetric tonic clonic activity lasting durations turn may impact outcome. The sections below provide

of less than 10 minutes on average, but at least 2 instances an overview of the most common epilepsy syndromes

of seizure lasting 20 minutes or more. The family notes for which febrile seizures are a central and often initial

that seizures have occurred almost every time the child symptom of the disorder (Table).

has had a febrile illness and often cluster over several

days. They report at least 1 seizure that occurred in the Genetic Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus

absence of fever. Development has been normal to date GEFS+ was first described in 1997 following recognition

and an EEG done by their primary provider was also of a pattern of febrile seizures followed later by the devel-

normal. opment of various epilepsy syndromes within the same

family [38]. As such, the syndrome is defined based on

the familial occurrence of febrile and afebrile seizures in

• What epilepsy syndromes are associated with at least 2 family members and can have a wide range of

febrile seizures? phenotypes. The most common presentation is of typical

febrile seizures which can persist beyond the typical upper

age limit of 6 years. Unprovoked generalized seizures of

While febrile seizures represent a benign and infrequent multiple types (ie, myoclonic, absence, atonic) occur at a

type of seizure in the majority of patients, rare circum- later age, though focal seizures may also be present. The

stances exists for which febrile seizures represent the first presence of focal onset seizures led to the naming change

symptom of an epilepsy syndrome. The severity of these from “generalized” epilepsy with febrile seizures plus as

syndromes can vary from milder phenotypes of Genetic it was previously referred. Seizure frequency and sever-

Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus syndrome (GEFS+) ity may vary between family members, as can response

to the more devastating epileptic encephalopathy of to treatment, making prognosis difficult to predict.

www.jcomjournal.com Vol. 24, No. 7 July 2017 JCOM 329

Febrile Seizures

As even in typical febrile seizures a family history of febrile By the second year, other seizure types including

seizure may be common, it may be difficult to diagnose myoclonic, atypical absence, clonic, and tonic seizures

the syndrome after the initial febrile seizure. However, arise. The EEG frequently begins to show generalized

if the family history is strong for a family member with spike wave and polyspike wave discharges. Seizures con-

a GEFS+ phenotype, one can appropriately counsel the tinue occurring frequently during early childhood, often

family on the possibility that a similar course may evolve. resulting in status epilepticus. Cognitive development

While the majority of GEFS+ patients have milder phe- begins to stagnate between the ages of 1 and 4 years

notypes, some more severe phenotypes can have cogni- with emergence of autistic traits and hyperactivity [44].

tive delays. Dravet syndrome falls within the spectrum Development may stabilize between the ages of 5 and

of GEFS+ and is a prime example of the phenotypic 16 years, but fails to demonstrate much improvement

continuum to more severe presentations in some patients. [44]. Higher frequency of seizures may correlate with

The syndrome is believed to be inherited in an auto- increase in cognitive impairment and behavior problems,

somal dominant fashion with incomplete penetrance. supporting the need for rapid diagnosis and appropriate

Multiple genes have been implicated as a cause, though therapy [44].

only 11.5% of families with clinical GEFS+ may have Over the years, several cases of atypical or borderline

mutations [39]. SCN1A, encoding the α-subunit of Dravet syndrome have been described, most highlight-

the voltage-gated sodium channel is most frequently ing the absence of myoclonic seizures [45]. Others may

reported in GEFS+ families, yet is only found in 10% present with primarily clonic or tonic-clonic type seizures

[38]. When associated with GEFS+, SCN1A mutations only [46]. Despite these differences, all cases share a

are more often missense type, whereas truncating and similar drug resistance and cognitive delay and are cat-

nonsense mutations are more commonly encountered egorized as Dravet syndrome.

in Dravet syndrome. Mutations in SCN1B encoding In 2001, Claus et al discovered the genetic alteration

the β1 subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel has in SCN1A responsible for 70% of Dravet syndrome cases

also been reported [40]. Finally, the GABA(A) receptor [47]. The disorder is inherited in an autosomal dominant

gamma 2 subunit GABRG2 has been found in <1% of fashion, though 40% to 80% of mutations resulting in

GEFS+ families [39]. The variability in causative genes Dravet syndrome are de novo [48]. Mutations can be

underscores the reasons for phenotype variability and it present in other family members, as this syndrome is part

is likely that other modifier genes are responsible for the of the spectrum of GEFS+, though parental phenotypes

heterogeneity within GEFS+ families [41]. are often much less severe. Approximately 50% of muta-

tions resulting in Dravet syndrome are truncating, while

Dravet Syndrome the other 50% are missense mutations involving splice

Dravet syndrome, often referred to as severe myoclonic site or pore forming regions leading to loss of function

epilepsy of infancy, was first described in 1978 and [49]. Finally, small and large chromosome rearrange-

has since become one of the most recognized genetic ments make up 2% to 3% of cases [50]. Other genes re-

epilepsy syndromes [42]. The clinical presentation often ported to result in Dravet syndrome include SCN1B and

begins with seizures in the first year of life, frequently GABRG2 mutations. In addition, PCDH19 can produce

in the setting of febrile illness. The initial seizures are a phenotype similar to Dravet syndrome in females and is

generalized or hemiclonic in the majority and are often discussed in more detail below.

prolonged evolving to status epilepticus. Unlike typical With the emergence of more rapid and cheaper forms

febrile seizures, one should suspect Dravet syndrome in of genetic testing, molecular diagnosis can now be made

children that present with repetitive bouts of complex earlier in life before all the typical clinical features of Dra-

febrile seizures or febrile status epilepticus, especially if vet syndrome arise. As a result, one might hope to alter

the associated seizure semiology is of hemiclonic type. In treatment strategy and gear therapy towards the most

addition, seizures in the setting of modest hyperthermia effective medications. While drug resistance is the norm

(ie, hot baths) should raise suspicion for this condition. for the condition, certain drugs such as benzodiazepines,

Commonly EEG and MRI are normal in the first year of valproate, and stiripentol may be most effective [43].

life and psychomotor development remains normal until Topiramate and levetiracetam have been reported as effi-

typically the second year of life [43]. cacious in small series, as has the ketogenic diet [51–55].

330 JCOM July 2017 Vol. 24, No. 7 www.jcomjournal.com

Case-based review

Varieties of medications which target sodium channels epilepsy from Dravet syndrome [59]. Seizures tend to

are known to exacerbate seizures in Dravet syndrome and improve with age and no particular antiepileptic drug

should be avoided, including lamotrigine, carbamazepine, has been found especially efficacious in the syndrome.

oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin [56]. In addition to main- Unlike Dravet syndrome, up to a third of patients with

tenance therapy, it is important to provide patients with a this syndrome may ultimately become seizure-free [59].

rescue plan for acute seizures in an effort to avoid status Cognitive development is normal prior to seizure

epilepticus. In addition, measures to avoid overheating onset in the majority of patients and most but not all

may provide additional benefit. patients will develop some cognitive impairment ranging

from mild to severe [59]. It is the more severe patients

Case 3 Continued that most often have overlapping characteristics of Dravet

After a careful history, the physician discovers syndrome, thus PCDH19 mutations should be investi-

that the child also has frequent myoclonic sei- gated in female patients with Dravet phenotype yet nega-

zures described as brief jerks of the extremities or sud- tive SCN1A testing.

den forward falls. The family notes they have seen these PCDH19 is a calcium-dependent adhesion protein

seizures more frequently since antiepileptic therapy was involved in neuronal circuit formation during develop-

started. The physician recognize that this child may have ment and in the maintenance of normal synaptic circuits

Dravet syndrome and suspect her medication may be in adulthood [60,61]. Disease causing mutations in

resulting in aggravation of seizures. PCDH19 are primarily missense (48.5%) or frameshift,

The physician decides to discontinue the medication nonsense, and splice-site mutations resulting in premature

suspected to aggravate the seizures and chooses to start termination codon [59]. Ninety percent of mutations are

the child on clobazam. The physician also begins evalu- de novo. When inherited, the disorder is X-linked and may

ation for Dravet syndrome by sending directed SCN1A come from an unaffected father or a mother that is simi-

genetic testing. The testing comes back negative for mu- larly affected or not, suggesting variable clinical severity in

tations in the SCN1A gene. females and gender-related protections in males [59].

Case 3 Continued

• What other investigations would be warranted Given the negative SCN1A testing, the physi-

now? cian chooses to pursue other genetic testing that

may explain the patient’s phenotype. A more extensive

“epilepsy gene panel” that includes 70 different genes

PCDH19 associated with epilepsy syndromes is ordered.

PCDH19 was first recognized as a cause of epilepsy and

mental retardation limited to females (EFMR), a syn- Hemiconvulsion-Hemiplegia Epilepsy

drome characterized by onset of seizures in infancy or Syndrome

early childhood with predominantly generalized type sei- Hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia epilepsy syndrome (HHE)

zures including tonic-clonic, absence, myoclonic, tonic, is characterized by the occurrence of unilateral convul-

and atonic [57]. Since that initial description, the pheno- sive status epilepticus followed by transient or permanent

type associated with PCDH19 mutations has expanded ipsilateral hemiplegia. The syndrome occurs in otherwise

to include female patients with primarily focal epilepsy, healthy children often in the setting of nonspecific febrile

variable cognitive impairment, and commonly onset with illness before the age of 4 years, with peak occurrence in

seizures in the setting of fever [58,59]. Typically seizures the first 2 years of life [62]. Seizures are characterized

begin around age 10 months presenting as a cluster of by unilateral clonic activity with EEG demonstrating

focal seizures in the setting of fever, often followed by rhythmic 2–3 Hz slow wave activity and spikes in the

a second cluster 6 months later [59]. Generalized sei- hemisphere contralateral to the body involvement. MRI

zures occur in a small proportion of patients (9%) and frequently demonstrates diffusion changes congruent

this feature, along with relatively fewer bouts of status with EEG findings, often in the perisylvian region. The

epilepticus and less frequent seizures (most monthly to hemiplegia that remains following status epilepticus is

yearly frequency) can differentiate PCDH19 associated permanent in up to 80% of cases [63]. As hemiplegia

www.jcomjournal.com Vol. 24, No. 7 July 2017 JCOM 331

Febrile Seizures

can occur following complex febrile seizures, it is recom- and continuous infusions titrated to burst suppression.

mended a minimum duration of hemiplegia of 1 week Immunomodulatory therapies are mostly ineffective as

be used to differentiate HHE [64]. Status epilepticus is well. The most useful therapy reported has been the

persistent in this syndrome and can last for hours if un- keto-genic diet with efficacy in up to 50% of patients

treated. Focal onset seizures will often continue to occur [72]. Recently, therapeutic hypothermia has also been

in the patient even after the status has been aborted. reported to be effective in 2 cases [73]. For the majority of

The etiology of HHE is variable with many cases idio- patients, therapy will remain ineffective and seizures will

pathic. Some cases are reported as symptomatic, as the continue for weeks to months with gradual resolution,

syndrome can present in the setting of other underlying though seizures often continue intermittently following

brain disorders such as Sturge-Weber and tuberous scle- the end of status epilepticus. Prognosis is poor for seizure

rosis complex. While some viruses have been proposed control and neurocognitive recovery with mortality of

as a cause, they are not found in the cerebral spinal fluid 30% reported [41].

of patients [65]. Treatment consists of rapid treatment

of status epilepticus with benzodiazepines as first-line Case 3 Conclusion

therapy, often followed by other intravenous antiepileptic The epilepsy gene panel ordered returns with

drugs as necessary. the result of a disease-causing mutation in the

PCDH19 gene. The child is diagnosed with PCDH19-

Febrile Infection–Related Epilepsy Syndrome associated epilepsy and is treated with phenobarbital. For

Febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) is the first years of life, she presents on average once per

presented under several names in the literature including year with a cluster of seizures in the setting of febrile

idiopathic catastrophic epileptic encephalopathy [66], illness which is often managed with short durations of

devastating encephalopathy in school-age children [67], scheduled benzodiazepines. Seizures slow by age 6. She

new-onset refractory status epilepticus [68], as well as has mild delays in speech and receives some accommoda-

fever-induced refractory epileptic encephalopathy syn- tions through her school system. By age 10, she has been

drome [69] and fever-induced refractory epileptic en- seizure-free for several years. She is able to be weaned off

cephalopathy in school-age children [70]. All describe medications without recurrence of seizures.

rare catastrophic epilepsy presenting in otherwise healthy

children during or days following a febrile illness. While Summary

febrile illness precedes the epilepsy in 96% of cases, up Febrile seizures are a common manifestation in early

to 50% of patients may not have fever at the time they childhood and very often a benign occurrence. For

present [41,65]. While age of onset is typically in early simple febrile seizures, minimal evaluation is necessary

childhood, presentation in adulthood also occurs. Initial and treatment typically not warranted beyond reassur-

seizures are often focal, presenting as forced lateral head ance and education of caregivers. For complex febrile

or eye deviation, oral or manual automatisms, and clonic seizures, additional evaluation in rare cases may suggest

movements of the face and extremities. Seizures will an underlying seizure tendency, though most follow a

inevitably progress to status epilepticus with ictal onset typical benign course of febrile seizures. In some cases, as

often multifocal predominating in the perisylvian regions needed benzodiazepines used for prolonged or recurrent

[41]. MRI is often normal at onset or shows only subtle febrile seizures may be of value. There are well described

swelling of the mesial temporal structures. Over months, epilepsy syndromes for which febrile seizures may be the

MRI often shows T2-hyperintensity and atrophy of the initial manifestation and it is paramount that providers

mesial temporal structures, though as many as 50% of recognize the signs and symptoms of these syndromes

MRIs may remain normal [71]. in order to appropriately counsel families and initiate

The evaluation for cause in FIRES is often unreward- treatment or referral when warranted. Providers should

ing. Inflammatory markers are typically absent from both have a high index of suspicion for these syndromes when

serum and CSF. CSF may show minimal pleocytosis with they encounter children that repeatedly present with

negative oligoclonal bands and absence of common recep- prolonged febrile seizures, clusters of febrile seizures,

tor antibodies. Treatment is equally unrewarding with or febrile seizures in addition to afebrile seizure events.

patients typically failing conventional antiepileptic drugs Early referral, diagnosis, and treatment has the potential

332 JCOM July 2017 Vol. 24, No. 7 www.jcomjournal.com

Case-based review

to alter outcome in some of these syndromes, thus the 1993;92:527–34.

importance of becoming familiar with these diagnoses. 17. Knudsen FU. Febrile seizures: treatment and prognosis. Epilep-

sia 2000;41:2–9.

Corresponding author: Anup D. Patel, MD, Nationwide 18. Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Shirts SB, Kurland LT. Factors prog-

Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH 43205, anup.patel@ nostic of unprovoked seizures after febrile convulsions. N Engl

J Med 1987;316:493–8.

nationwidechildrens.org.

19. Teng D, Dayan P, Tyler S, et al. Risk of intracranial patho-

Financial disclosures: Dr. Patel disclosed that he has consulted logic conditions requiring emergency intervention after a first

complex febrile seizure episode among children. Pediatrics

for GW Pharmaceuticals and Supernus and is on the Scientific

2006;117:304–8.

Advisory Board for UCB Pharma. 20. Janszky J, Schulz R, Ebner A. Clinical features and surgical

outcome of medial temporal lobe epilepsy with a history of

References complex febrile convulsions. Epilepsy Res 2003;55:1–8.

1. Shinnar S, Glauser TA. Febrile seizures. J Child Neurol 2002; 21. Capovilla G, Mastrangelo M, Romeo A, Vigevano F. Recom-

17 Suppl 1:S44–52. mendations for the management of «febrile seizures»: Ad

2 . Kang J-Q, Shen W, Macdonald RL. Why does fever trigger Hoc Task Force of LICE Guidelines Commission. Epilepsia

febrile seizures? GABAA receptor γ2 subunit mutations associ- 2009;50 Suppl 1:2–6.

ated with idiopathic generalized epilepsies have temperature- 22. Shinnar S, Hesdorffer DC, Nordli DR Jr, et al. Phenomenology

dependent trafficking deficiencies. J Neurosci 2006;26:2590–7. of prolonged febrile seizures: results of the FEBSTAT study.

3. Baumann RJ, Duffner PK. Treatment of children with simple Neurology 2008;71:170–6.

febrile seizures: the AAP practice parameter. American Academy 23. Camfield P, Camfield C, Gordon K, Dooley J. What types of

of Pediatrics. Pediatr Neurol 2000;23:11–7. epilepsy are preceded by febrile seizures? A population-based

4. Tarkka R, Rantala H, Uhari M, Pokka T. Risk of recurrence study of children. Dev Med Child Neurol 1994;36:887–92.

and outcome after the first febrile seizure. Pediatr Neurol 24. Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in chil-

1998;18:218–20. dren who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med

5. Berg AT, Shinnar S. Complex febrile seizures. Epilepsia 1976;295:1029–33.

1996;37:126–33. 25. Hamati-Haddad A, Abou-Khalil B. Epilepsy diagnosis and lo-

6. Berg AT, Shinnar S. Unprovoked seizures in children with fe- calization in patients with antecedent childhood febrile convul-

brile seizures: short-term outcome. Neurology 1996;47:562–8. sions. Neurology 1998;50:917–22.

7. Audenaert D, Schwartz E, Claeys KG, et al. A novel GABRG2 26. Davies KG, Hermann BP, Dohan FC Jr, et al. Relationship of

mutation associated with febrile seizures. Neurology 2006; hippocampal sclerosis to duration and age of onset of epilepsy,

67:687–90. and childhood febrile seizures in temporal lobectomy patients.

8. Dube CM, Brewster AL, Baram TZ. Febrile seizures: mecha- Epilepsy Res 1996;24:119–26.

nisms and relationship to epilepsy. Brain Dev 2009;31:366–71. 27. Kimia AA, Ben-Joseph E, Prabhu S, et al. Yield of emergent

9. Vestergaard M, Christensen J. Register-based studies on febrile neuroimaging among children presenting with a first complex

seizures in Denmark. Brain Dev 2009;31:372–7. febrile seizure. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:316–21.

10. Berkovic SF, Petrou S. Febrile seizures: traffic slows in the heat. 28. Abou-Khalil B, Andermann E, Andermann F, et al. Temporal

Trends Molecul Med 2006;12:343–4. lobe epilepsy after prolonged febrile convulsions: excellent out-

11. Practice parameter: the neurodiagnostic evaluation of the come after surgical treatment. Epilepsia 1993;34:878–83.

child with a first simple febrile seizure. American Academy of 29. Cendes F. Febrile seizures and mesial temporal sclerosis. Curr

Pediatrics. Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Opin Neurol 2004;17:161–4.

Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures. Pediatrics 1996;97:769–72; 30. Hesdorffer DC, Chan S, Tian H, et al. Are MRI-detected brain

discussion 773–765. abnormalities associated with febrile seizure type? Epilepsia

12. Fukuyama Y, Seki T, Ohtsuka C, et al. Practical guidelines for 2008;49:765–71.

physicians in the management of febrile seizures. Brain Dev 31. Patel AD, Vidaurre J. Complex febrile seizures: a practical guide

1996;18:479–84. to evaluation and treatment. J Child Neurol 2013;28:762–67.

13. Neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile 32. Pavlidou E, Tzitiridou M, Panteliadis C. Effectiveness of inter-

seizure. Pediatrics 2011;127:389–94. mittent diazepam prophylaxis in febrile seizures: long-term pro-

14. Guedj R, Chappuy H, Titomanlio L, et al. Risk of bacterial spective controlled study. J Child Neurol 2006;21:1036–40.

meningitis in children 6 to 11 months of age with a first simple 33. Offringa M, Newton R. Prophylactic drug management for

febrile seizure: a retrospective, cross-sectional, observational febrile seizures in children (Review). Evid Based Child Health

study. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:1290–7. 2013;8:1376–485.

15. Wo SB, Lee JH, Lee YJ, et al. Risk for developing epilepsy and 34. Gordon KE, Dooley JM, Camfield PR, et al. Treatment of

epileptiform discharges on EEG in patients with febrile seizures. febrile seizures: the influence of treatment efficacy and side-

Brain Dev 2013;35:307–11. effect profile on value to parents. Pediatrics 2001;108:1080–8.

16. Green SM, Rothrock SG, Clem KJ, et al. Can seizures be the 35. Maytal J, Shinnar S. Febrile status epilepticus. Pediatrics 1990;

sole manifestation of meningitis in febrile children? Pediatrics 86:611–6.

www.jcomjournal.com Vol. 24, No. 7 July 2017 JCOM 333

Febrile Seizures

36. Ahmad S, Marsh ED. Febrile status epilepticus: current state the ketogenic diet for intractable childhood epilepsy: Korean

of clinical and basic research. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2010;17: multicentric experience. Epilepsia 2005;46:272–9.

150–4. 56. Chiron C. Current therapeutic procedures in Dravet syndrome.

37. Maytal J, Shinnar S, Moshe SL, Alvarez LA. Low morbid- Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53 Suppl 2:16–8.

ity and mortality of status epilepticus in children. Pediatrics 57. Dibbens LM, Tarpey PS, Hynes K, et al. X-linked protocad-

1989;83:323–31. herin 19 mutations cause female-limited epilepsy and cognitive

38. Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Generalized epilepsy with febrile impairment. Nat Genet 2008;40:776–81.

seizures plus. A genetic disorder with heterogeneous clinical 58. Specchio N, Marini C, Terracciano A, et al. Spectrum of pheno-

phenotypes. Brain 1997;120 (Pt 3):479–90. types in female patients with epilepsy due to protocadherin 19

39. Marini C, Mei D, Temudo T, et al. Idiopathic epilepsies with mutations. Epilepsia 2011;52:1251–7.

seizures precipitated by fever and SCN1A abnormalities. Epi- 59. Marini C, Darra F, Specchio N, et al. Focal seizures with af-

lepsia 2007;48:1678–85. fective symptoms are a major feature of PCDH19 gene-related

40. Wallace RH, Scheffer IE, Parasivam G, et al. Generalized epi- epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012;53:2111–9.

lepsy with febrile seizures plus: mutation of the sodium channel 60. Hirano S, Yan Q, Suzuki ST. Expression of a novel protocad-

subunit SCN1B. Neurology 2002;58:1426–9. herin, OL-protocadherin, in a subset of functional systems of

41. Cross JH. Fever and fever-related epilepsies. Epilepsia 2012;53 the developing mouse brain. J Neurosci 1999;19:995–1005.

Suppl 4:3–8. 61. Kim SY, Chung HS, Sun W, Kim H. Spatiotemporal expression

42. Dravet C. Les epilepsies graves de l’enfant. Vie Med 1978; pattern of non-clustered protocadherin family members in the

8:543–8. developing rat brain. Neuroscience 2007;147:996–1021.

43. Dravet C. Dravet syndrome history. Dev Med Child Neurol 62. Gastaut H, Poirier F, Payan H, et al. H.H.E. syndrome; hemi-

2011;53 Suppl 2:1–6. convulsions, hemiplegia, epilepsy. Epilepsia 1960;1:418–47.

44. Wolff M, Casse-Perrot C, Dravet C. Severe myoclonic epilepsy 63. Panayiotopoulos CP. The epilepsies: seizures, syndromes and

of infants (Dravet syndrome): natural history and neuropsycho- management. Oxfordshire (UK): Bladon Medical Publishing;

logical findings. Epilepsia 2006;47 Suppl 2:45–8. 2005.

45. Ogino T, Ohtsuka Y, Amano R, et al. An investigation on the 64. Chauvel P, Dravet C. The HHE syndrome. In: Roger J, Bureau

borderland of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Jap J Psych M, Dravet C, editors. Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood

Neurol 1988;42:554–5. and adolescence. 4th ed. John Libbey; 2005; 247–60.

46. Kanazawa O. Refractory grand mal seizures with onset during 65. Nabbout R. FIRES and IHHE: Delineation of the syndromes.

infancy including severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Brain Epilepsia 2013;54 Suppl 6:54–6.

Dev 2001;23:749–56. 66. Baxter P, Clarke A, Cross H, et al. Idiopathic catastrophic

47. van der Worp HB, Claus SP, Bar PR, et al. Reproducibility of epileptic encephalopathy presenting with acute onset intractable

measurements of cerebral infarct volume on CT scans. Stroke status. Seizure 2003;12:379–87.

2001;32:424–30. 67. Mikaeloff Y, Jambaque I, Hertz-Pannier L, et al. Devastating

48. Wang JW, Kurahashi H, Ishii A, et al. Microchromosomal dele- epileptic encephalopathy in school-aged children (DESC): a

tions involving SCN1A and adjacent genes in severe myoclonic pseudo encephalitis. Epilepsy Res 2006;69:67–79.

epilepsy in infancy. Epilepsia 2008;49:1528–34. 68. Wilder-Smith EP, Lim EC, Teoh HL, et al. The NORSE (new-

49. Madia F, Striano P, Gennaro E, et al. Cryptic chromosome onset refractory status epilepticus) syndrome: defining a disease

deletions involving SCN1A in severe myoclonic epilepsy of entity. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:417–20.

infancy. Neurology 2006;67:1230–5. 69. van Baalen A, Hausler M, Boor R, et al. Febrile infection-

50. Marini C, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, et al. SCN1A duplications related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): a nonencephalitic encepha-

and deletions detected in Dravet syndrome: implications for lopathy in childhood. Epilepsia 2010;51:1323–8.

molecular diagnosis. Epilepsia 2009;50:1670–8. 70. Nabbout R, Vezzani A, Dulac O, Chiron C. Acute encepha-

51. Coppola G, Capovilla G, Montagnini A, et al. Topiramate as lopathy with inflammation-mediated status epilepticus. Lancet

add-on drug in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy: an Italian Neurol 2011;10:99–108.

multicenter open trial. Epilepsy Res 2002;49:45–8. 71. Howell KB, Katanyuwong K, Mackay MT, et al. Long-term

52. Nieto-Barrera M, Candau R, Nieto-Jimenez M, et al. Topira- follow-up of febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome. Epi-

mate in the treatment of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. lepsia 2012;53:101–10.

Seizure 2000;9:590–4. 72. Nabbout R, Mazzuca M, Hubert P, et al. Efficacy of keto-

53. Striano P, Coppola A, Pezzella M, et al. An open-label trial of genic diet in severe refractory status epilepticus initiating fever

levetiracetam in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Neurol- induced refractory epileptic encephalopathy in school age chil-

ogy 2007;69:250–4. dren (FIRES). Epilepsia 2010;51:2033–7.

54. Caraballo RH, Cersosimo RO, Sakr D, et al. Ketogenic diet in 73. Lin JJ, Lin KL, Hsia SH, Wang HS. Therapeutic hypothermia

patients with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 2005;46:1539–44. for febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome in two patients.

55. Kang HC, Kim YJ, Kim DW, Kim HD. Efficacy and safety of Pediatr Neurol 2012;47:448–50.

Copyright 2017 by Turner White Communications Inc., Wayne, PA. All rights reserved.

334 JCOM July 2017 Vol. 24, No. 7 www.jcomjournal.com

View publication stats

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Campus Sexual Violence - Statistics - RAINNDocumento6 pagineCampus Sexual Violence - Statistics - RAINNJulisa FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- 220hp Caterpillar 3306 Gardner Denver SSP Screw Compressor DrawingsDocumento34 pagine220hp Caterpillar 3306 Gardner Denver SSP Screw Compressor DrawingsJVMNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Energy Optimization of A Large Central Plant Chilled Water SystemDocumento24 pagineEnergy Optimization of A Large Central Plant Chilled Water Systemmuoi2002Nessuna valutazione finora

- PV2R Series Single PumpDocumento14 paginePV2R Series Single PumpBagus setiawanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Beckhoff Service Tool - USB StickDocumento7 pagineBeckhoff Service Tool - USB StickGustavo VélizNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Abfraction, Abrasion, Biocorrosion, and The Enigma of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: A 20-Year PerspectivejerdDocumento14 pagineAbfraction, Abrasion, Biocorrosion, and The Enigma of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: A 20-Year PerspectivejerdLucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- TCJ Series: TCJ Series - Standard and Low Profile - J-LeadDocumento14 pagineTCJ Series: TCJ Series - Standard and Low Profile - J-LeadgpremkiranNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Tetra Pak Training CatalogueDocumento342 pagineTetra Pak Training CatalogueElif UsluNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Liebherr 2956 Manual de UsuarioDocumento27 pagineLiebherr 2956 Manual de UsuarioCarona FeisNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Olivares VsDocumento2 pagineOlivares VsDebbie YrreverreNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Cleaning of Contact Points and Wiring HarnessesDocumento3 pagineCleaning of Contact Points and Wiring HarnessesRafa Montes MOralesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Remote Control Unit Manual BookDocumento21 pagineRemote Control Unit Manual BookIgor Ungur100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Issue of HomosexualityDocumento4 pagineIssue of HomosexualityT-2000Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- TM - 1 1520 237 10 - CHG 10Documento841 pagineTM - 1 1520 237 10 - CHG 10johnharmuNessuna valutazione finora

- Legg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsDocumento35 pagineLegg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsAsad ChaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Biology - Cell City AnswersDocumento5 pagineBiology - Cell City AnswersDaisy be100% (1)

- Emerging Re-Emerging Infectious Disease 2022Documento57 pagineEmerging Re-Emerging Infectious Disease 2022marioNessuna valutazione finora

- L Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelDocumento1 paginaL Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelL_Addison_DiehlNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- CFPB Discount Points Guidence PDFDocumento3 pagineCFPB Discount Points Guidence PDFdzabranNessuna valutazione finora

- Uttarakhand District Factbook: Almora DistrictDocumento33 pagineUttarakhand District Factbook: Almora DistrictDatanet IndiaNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Index Medicus PDFDocumento284 pagineIndex Medicus PDFVania Sitorus100% (1)

- Intentions and Results ASFA and Incarcerated ParentsDocumento10 pagineIntentions and Results ASFA and Incarcerated Parentsaflee123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7 Unemployment, Inflation, and Long-Run GrowthDocumento21 pagineChapter 7 Unemployment, Inflation, and Long-Run GrowthNataly FarahNessuna valutazione finora

- EB Research Report 2011Documento96 pagineEB Research Report 2011ferlacunaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Dando Watertec 12.8 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Documento2 pagineDando Watertec 12.8 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Dando Drilling IndonesiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Complement Fixation Test: Process Testing For Antigen Semi-Quantitative Testing References External LinksDocumento2 pagineComplement Fixation Test: Process Testing For Antigen Semi-Quantitative Testing References External LinksYASMINANessuna valutazione finora

- Constantino V MendezDocumento3 pagineConstantino V MendezNīc CādīgālNessuna valutazione finora

- BKM 10e Ch07 Two Security ModelDocumento2 pagineBKM 10e Ch07 Two Security ModelJoe IammarinoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Chap 6 - Karen HorneyDocumento95 pagineChap 6 - Karen HorneyDiana San JuanNessuna valutazione finora

- SA 8000 Audit Check List VeeraDocumento6 pagineSA 8000 Audit Check List Veeranallasivam v92% (12)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)