Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Education in Adult BLS Programs

Caricato da

moonstar888Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Education in Adult BLS Programs

Caricato da

moonstar888Copyright:

Formati disponibili

E D U C A T I O N ISSUES

basic life support; education; motivation; resuscitation; simplification

Educationin Adult Basic Life Support

Training Programs

From Tufts University and Baystate Loring S Flint, Jr, MD* The Panel on Educational Issues in Adult Basic Life Support

Medical Center, Springfield, John E Billi, MD t Training Programs reviewed the characteristics of adult/earners,

Massachusetts;* the University of Karen Kelly, MSRN*

Michigan Medical School, Ann aspects of educational theory, issues concerning barriers to

Arbor;r Kelly Thomas Associates, Lynn Mandel, PhD~ learning and performing CPR,and issues concerning testing and

Alexandria, Virginia;; University of Lawrence Newell, EdD, NREMT-P"

evaluation.

Washington 5choo! of Medicine, Edward R Stapleton, EMT-P~

SeattIe;~ the Health and Safety The pane/made the following recommendations: a comprehen-

Division of the American National

Red Cross, Washington, DC;IIand sive evaluation of the basic life support program with the goal of

University Hospital, State University improving the program design and educational tools must be

of New Yorh, Stony Brook.¶ initiated; adult programs must be designed to motivate layper-

sons to become trained in CPR,as well as to target relatives and

friends of high-risk individuals; and emotional and attitudinal

issues, including the student's reluctance to act in an emergen-

cy, must be addressed. Programs must incorporate information

on the willingness of an individual to perform CPR; CPR

programs must be simplified and focus on critical success fac-

tors; flexible educational approaches in programs are encour-

aged; flexible programming that addresses the needs of the

allied health professional is encouraged; formal testing should

be eliminated for layperson programs; and formal testing for

health care providers and instructors should be continued.

[Flint LS, Billi JE, Kelly K, Mandel L, Newell L, Stapleton ER:

Education in adult basic life support training programs. Ann

ErnergMed February 1993;22 (pt 2):468-474.]

OVERVIEW OF ISSUES

LearningWhat is learning? To date, there is still no univer-

sally accepted definition of learning. As with many con-

cepts that are basic to a discipline, learning is not easily

defined, because we can never see learning directly or

study it in isolation.

Generally, the term learning has been used to describe

either a process, product, or function. If learning is

viewed as a process, its success is defined in terms of the

method used to modify behavior. If learning is viewed as

resulting in a product, its success is defined in terms of

the outcome, not the method by which the outcome was

2 0 2 /468 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEOICINE 22:2 PART 2 FEBRUARY 1993

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

derived. If learning is viewed as a function, then its suc- successful BLS programs have been m this area.

cess is defined in term.s of specific critical aspects of the The final element involves providing care until help

process, such as motivation. Learning is a relatively per- arrives. This is a complex cognitive and affective process

manent process, resulting from practice and reflected in a involving decision-making and psychomotor skills.

change of performance. 1 Performing these skills requires that a person trained in

Classic educational theorists >4 have offered what has CPR retain the knowledge to perform them.

become perhaps the most generally accepted description Adult Learners Four adult learning characteristics must

of learning as a complex process that involves the emo- be addressed in any BLS program revisions: self-direction,

tions (affective domain), body (psychomotor domain), experience, psychomotor skill-learning factors, and skill

and the brain. acquisition variables. Some of these characteristics were

What should course participants learn? To date, basic recognized and integrated into the last major curriculum

life support (BLS) programs have focused on delivering an revision in the mid-1980s.

abundance of information in a relatively short time, with The first concern, self-direction, is the well-established

the expectation that when confronted with an emergency, principle that adults want to set their own learning pace,

the course taker will somehow be able to sort through the use their own learning style, keep learning flexible, and

information, grasp the few items that are truly important, maintain their own structure for learning new informa-

and take action. Present programs place emphasis upon tion. The most common motivation of adults for under-

rote memorization of psychomotor performance criteria taking a learning activity is the anticipation of using the

for rescue breathing, relieving airway obstruction, and skill or knowledge. 12,13 If an adult learner anticipates

CPR. In CPR alone, over 50 individual critical perfor- using new knowledge or skill in the immediate future,

mance criteria are identified. attention is focused and learning occurs. However, if the

As a radical departure, one should consider that there adult is taking a course with the anticipation of using the

are really only four basic elements that people want to skill at some future date with some vague notion of

learn: 1) preventing injury/illness, 2) recognizing an becoming a heroic lifesaver, learning is more diffuse and

emergency, 3) getting more help, and 4) providing basic unfocused. If the adult learner's motivation is to acquire a

care until help arrives. card to meet some external regulation, learning also is

The first element - - how to prevent an unwanted inci- focused differently. Each of these motivations causes the

dent (such as serious injury from a motor vehicle accident adult learner's characteristic of self-direction to change.

or sudden illness resulting from cardiovascular disease) - - This unstable characteristic has significant relevance to

seems rather straightforward, but many unanswered ques- program design. Adults seek out learning to solve a prob-

tions remain. There is a debate over whether one can truly lem which they have defined in their own way.

effect a change in a person's behavior - - in essence, modi- Unless a variety of options are available for adults to

fying a life-style. One questions what strategies work best use BLS information, knowledge, and skills, a large audi-

for different age groups. One can strive to measure the ence of potential heart savers will be lost. Aduh learners

outcome of these efforts in concrete terms to determine if must be given choices in their pursuit of knowledge. The

they have been successful. One recognizes the ability to curriculum must be flexible, and instructors must be

see the illness/injury that is prevented. Clearly, there is allowed to build a curriculum for an iridividual or group

inconclusive evidence to support any contention that and fit it to the learners' objectives for seeking the knowl-

life-styles have been impacted by participation in BLS pro- edge.

grams. The second issue, experience, is related to the role

The next two elements involve the decision to act. experience plays in adult knowledge. As people grow and

The ability to recognize the signals of an emergency and develop, they have an increasing reservoir of experience

knowing when and how to summon help are perhaps the that becomes a rich foundation and source for learning.

most important elements of the four basic components Furthermore, they attach more meaning to learnings they

that people want to learn in BLS courses. Yet, an have gamed through experience than those they acquire

abundance of studies 5-t 1 have demonstrated over the past passively. ~* This compels us to design BLS programs to

25 years that people delay seeking help either because of a recognize those experiences and use them to help learners

reluctance to admit that an emergency exists, an inability expand their knowledge. The primary methods should be

to overcome the ambiguity of the situation, or they do not experiential - - that is, discussion, problem-solving cases,

know it is an emergency. Again, one must question how and simulation. Even field experience can be used as a

FEBRUARY 1993 22:2 PART 2 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 469/ 2 03

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

learning opportunity for selected populations of adult in general, educators point to the time spent practicing

learners. successfully with feedback from an instructor as being

The third characteristic relates to psychomotor skill positively related to skill acquisition. It has been shown

factors. Adults, as they mature (and depending on their that using a simplified CPR curriculum results in substan-

personal activity levels), may lose some psychomotor tially better skill retention, even after 12 months. 23

capacity. As mentioned earlier, an adult learner's Another study reported that increases in skill practice

motivation may cause them to be uninterested in the resulted in a considerably higher level of skill mastery

performance aspects of BLS. Despite these variable charac- at completion of the course and at five months after

teristics, classic research still supports the integration of training. 24 It also has been shown that less stringent train-

distributive practice and feedback during the acquisition ing and evaluation criteria resulted in greater retention at

of any psychomotor skill. 15 The implication of this char- three- and eight-month intervals.25, 26 Just the viewing of

acteristic for BLS program improvements points to the videotapes showed promise for reversing skill

need for a serious look at the outcome expectations with degradation. 2r

the current curriculum. Even with the promise of better skill acquisition and

The fourth issue is skill acquisition variables. The retention, we still have not identified strategies that would

newer use of the word skill goes beyond the classic three result in people overcoming barriers to action and conse-

domains of learning: cognitive, affective, and psychomo- quently acting sooner when faced with an emergency

tor skills. Research integrates all three domains and illus- In BLS courses, it is explained that heart attacks and

trates how we acquire skill over time with experience, cardiac arrests occur most frequently among older adult

practice, and deliberative rationality 16,17 Information is populations. Because BLS programs focus on diseases that

available about how we use knowledge and experience to can begin earlier in an adult's life but do not take their toll

refine the performance aspects of any skill. For example, until later, one should consider the need to adopt strate-

with experience and reflection, the way we manage a gies that target specific populations with specific

resuscitation attempt will change over time. The way we messages.

may use a curriculum with a group of learners motivated Approaches must be flexible and consider a number of

by the need for a card versus a group motivated by the critical learning characteristics and optimum conditions

need to know how to save their infants on apnea monitors that foster adult learning. Adults learn best in a nonthreat-

will also change and improve. ening environment that can provide trust and a sense of

Careful study of the skill acquisition process shows that accomplishment and self-worth. Teaching and learning

we usually pass through at least five stages of qualitatively among adults therefore must be an integrated process that

different perceptions of the task as our skill at the task fosters a spirit of inquiry and allows the participant to

improves. The stages have been labeled novice, advanced easily transfer information gained into solving practical

beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. This information problems.

must be applied to our outcome expectations of BLS pro- Barriers to Learning and Performing CPR A large number

grams. Learners can be helped along this continuum of of cardiac arrests take place in the home. Thus, the person

skill acquisition over time, usually years. Expectations of most likely to be on the scene of a witnessed arrest is a

learners on completion of a learning activity must be spouse or loved one. Numerous surveys of CPR training

related to their previous experience with learning and have been conducted through telephone interviews with

applying the skill. What is taught during review sessions the public and surveys of CPR class participants.28, 29

must be relative to the learners' experience and their skill They show that the majority of trainees were under 40. In

acquisition stage. Seattle, most CPR students take training through their

Retention Numerous retention studies document seri- place of business, and many are required to take the

ous skill deterioration among both laypersons and profes- course.

sionals within 6 months to 1 year following training. 18-22 Few trainees are older than 50 or have overt coronary

This information on skill retention by course participants heart disease (CHD) or even high blood pressure in the

raised troublesome questions. Is the problem with our family Few individuals choose to be trained because they

students, the curriculum, or with BLS instructors? or a family member has coronary disease.

There are strategies that help improve skill acquisition Why don't older citizens take CPR classes? Why don't

and retention. In regard to psychomotor skill achievement family members of patients at risk for sudden cardiac

death learn CPR? While there is research that correlates

2 0 4/4 7 0 ANNALS OF EMER6ENCY MEDI01NE 22:2 PART 2 FEBRUARY 1993

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

CPR training with demographic characteristics and the CPR, some of who were exposed to disagreeable charac-

presence of CHD, there has been no attempt to probe why teristics such as alcohol on breath, dentures, visible blood,

people choose to be trained, or more importantly, why and vomitus, revealed that none of the bystanders report-

they choose not to be trained. 3o ed that they hesitated to perform CPR. 35 However, this

There are several potential barriers to choosing to be study does not account for the possibility that bystanders

trained and to performing in an emergency. One of the at the arrests where lay CPR was not performed, avoided

greatest of these potential barriers is the fear of imperfect CPR because of the conditions of the victims.

performance. No body of research deals specifically with Regardless of skill level, if a resuscitation is unsuccess-

this area. Numerous studies have shown that initial per- ful, it is logical to assume that some bystanders will feel

formance on most skills can meet at least relaxed criteria, guih. In Seattle, citizens who were given telephone CPR

but subjects have difficulty putting all the skills together instructions by a dispatcher were asked about adverse

and retention is poor. Extensive observation and effects. The interviewer reported that for many subjects,

interviews with class participants have revealed great the interview itself acted as a debriefing.

fear in the areas of practicing/testing in class and/or not To the lay public, there is a fear of infection in perform-

doing the skill well enough in an actual emergency. ing CPR. In many areas this translates as fear of infection

A second barrier is a reluctance to take charge in an by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), especially

emergency situation. Individuals have reported a fear of in performing mouth-to-mouth ventilation. This fear

taking responsibility for their actions. influences whether people choose to be trained and

Another barrier is the ability to recognize the situation whether they will perform CPR. The actual risk of trans-

and make the decision to access prompt medical care. In a mission of HIV is extremely low or zero, but the fear of

recent study, there was a reported delay of from two to disease transmission is out of proportion to this fact.

four hours between the onset of symptoms of an acute In a survey of participants in a mass training course,

myocardial infarction and arrival at the hospital. 31 Patient more than 90% stated they would perform CPR on a

denial also plays a key role and leads to further delay. stranger. However, when asked about a confirmed or sus-

Anxiety, guilt, and other psychosocial factors (such as pected AIDS patient, fewer than 45% surveyed (immedi-

one's self-perception) also are other barriers that must be ately after training) and 32% (on follow-up) would

addressed. Family members learning CPR can cause anxi- perform CPR.

ety in high-risk patients. It has been reported that high- In a survey of BLS instructors in Virginia, of those

risk patients whose families had received CPR training respondents who reported they had actually performed

were more anxious three months later than control groups CPR, 40% had hesitated to perform mouth-to-mouth ven-

of high-risk patients whose families received education tilation, and 40% reported having witnessed another

about risk factors or no intervention at all. 32 There were provider hesitate. 36 When presented with possible rescue

no adverse psychological effects on the trained family scenarios, 97% would perform mouth-to-mouth ventila-

members. tion on a child, 54% would perform mouth-to-mouth

Families of hospitalized CHD patients have been ventilation on a female college student, only 10% would

reported to be more anxious before CPR training than perform mouth-to-mouth ventilation on a victim of a

were the families of nonhospitalized CHD patients and heroin overdose, 18% would perform mouth-to-mouth

families of a control group. Immediately after training and ventilation on a male on a San Francisco bus, and 29%

two months later, there was no difference among the would perform mouth-to-mouth ventilation on a male at a

groups. The trained family members showed a decline in New York City football game.

anxiety. The authors concluded that knowledge of CPR In an unpublished study, telephone surveys were con-

may be therapeutic for families of CHD patients. 33 ducted of randomly selected citizens in Seattle, New York

Self-perception is another perceived barrier; many City, and Lincoln, Nebraska. Almost 40% of the respon-

laypersons feel that they are too old, weak, or ill to learn dents in all three cities expressed fear of infection from the

and perform CPR. Elderly and depressed family members, training mannequin and between 70% and 75% feared

in some circumstances, were less likely to demonstrate infection from performing mouth-to-mouth ventilation on

adequate CPR skillsY a stranger. 3r More than 70% of the respondents in the

Rescuers may be afraid of close contact with victims three cities expressed greater willingness to perform

who may have unpleasant physical characteristics. mouth-to-mouth ventilation if they had a face mask or

Personal interviews of bystanders who had performed shield. This does not, however, mean that they would do

FEBRUARY 1993 22:2 PART 2 ANNALS OF EMER6ENCY MEDfCINE 4 71/ 205

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

nothing to help. Almost all said they would call 911, and than "educating," test security is a high priority because

at least 85% would check for consciousness. the score on an examination has practical implications. In

Evaluation and Testing The goal of BLS programs must a course with a purely educational focus, test security is

be to educate, not to test and certify. Several years ago, the not as important. The examination can be made available

American Heart Association removed "certified" from its to the participant as a study guide or can be used as a

cards and literature replacing it with "course completion." pretest to h d p the faculty understand the strengths and

Despite this, the implications of certification still persist. weaknesses of a particular group. Open-book review or

Resuscitation education programs must emphasize in class discussion after the examination is completed also

instructor training and instructor materials that the goal is has been very helpful as an approach to improve the cog-

to improve each participant's ability to respond to a car- nitive knowledge of an individual. The instructor can

diac or respiratory arrest, taking into account that person's review questions missed by the participants, discussing

likely role and prior training. This shift in philosophy will not only the correct answer but also the knowledge and

have different implications for the educational network problem-solving process required to answer correctly.

based on whether the course participants are laypersons Acquisitions of skills can be evaluated through obser-

or health care providers. vation of the participant performing CPR. The participant

Adults attend educational programs to acquire the should be informed that the results will not be used to

skills and knowledge to solve a problem. When evaluation grade the participant or determine passing; rather, they

(testing) of a participant is used to determine whether that will be used to identify to the participant and instructor

person "passes" or "fails" a course, the evaluation may those areas needing further work. The results of the

increase anxiety and impair the acquisition of skills. More evaluation of psychomotor skills should be used solely

importantly, the self-doubt or negative feedback stimulat- for participant feedback, instructor feedback, and educa-

ed by the test may inhibit the participant from performing tional quality control.

the skills during a real emergency.

Standards used by BLS instructors in the testing of par- COMMENTARY

ticipants vary greatly. 3s Moreover, there are no data to The panelists and attendees at the National Conference

support the concepts that the technical correctness of a on CPR and Emergency Cardiac Care were in general

lay rescuer who attempts CPR or the interval since last agreement that the characteristics of adult learners

training correlates with the likelihood of a favorable out- are addressed to some degree in the BLS educational

come. There is, therefore, no rationale for discouraging a programs. It was recommended at the 1985 conference,

participant from performing CPR in a real setting based and repeated again in the 1992 conference, that the AHA

on test results during a course. Evaluation of the partici- begin a comprehensive evaluation of its current BLS

pants skills and knowledge is essential, but not to deter- teaching and testing materials and that these materials be

mine whether a participant passes. adjusted to appropriate learning levels and focused on tar-

In the educational paradigm, evaluation (testing) plays geted audiences. A number of changes were made after

a key role, providing essential information to the partici- the 1985 conference. A modular course curriculum was

pant, the instructors, and the course leaders. Evaluation implemented; programs were targeted to high-risk groups,

helps the participant identify areas of personal difficulty especially in the pediatric and neonatal areas. There is

needing further work and motivates the participant to still, however, a lot of work to be accomplished in this

learn. Evaluation provides instructors with insight into a area.

particular participant's problems and allows them to CPR courses must reach older citizens and others who

improve the effectiveness of rendition efforts. Evaluation have resisted training. Programs must focus on the fact

results can provide the course leaders with information that more than 70% of cardiac arrests.take place in the

about the participant population enrolled in the course. It home, and the first responder is most likely a loved one.

can provide information about the strengths and weak- As such, families of high-risk individuals play a key role

nesses of the course, the choice of curriculum, the in developing emergency action plans that will indeed

method of presentation, and the overall assessment of save lives. It must be emphasized that courses can be flex-

whether the program was successful. ible, can reduce the time required, and, as an added value,

Acquisition of knowledge may be evaluated through may improve the quality of one's life.

either oral or written examination. When written exami- Students should be trained to rehearse making

nations are used in a course aimed at "certifying" rather decisions about how and on whom they will perform the

2 0 6 /4 7 2 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 22:2 PART 2 FEBRUARY1993

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

skills they have just learned. Decisions on resuscitation fessionals and instructors, a number of statements were

are not simply "yes/no" but depend on the situation and made that these individuals should be held to a higher

the rescuer's relationship to the victim. The choice is not standard of performance for CPR, as they may indeed

only between walking away or performing complete CPR. have a job-related responsibility. However, against this

With well-trained first responders, improved emergency point of view is the fact that the program is, and should

medical services systems, and rapid defibrillation, survival remain, an educational effort,

can be increased if laypersons do nothing more than call Major responsibilities of the AHA in the field of resus-

911 (or the appropriate emergency number). citation are to identify the besL way to perform resuscita-

Training must be less threatening, and skills must be tion based on the available scientific data and to develop

simplified. Concentration on those skills considered educational programs to equip individuals with this

essential should improve performance and retention and knowledge and skills. Stronger emphasis on evaluation of

should make instructor and refresher training more attrac- these individuals' skills and utilization of this evaluation

tive for lay students. A first step in this process would be as an effort to improve the quality of CPR programs is a

to simplify the multiple performance steps and training key focus for the future.

scenarios. However, it is still to be determined what the Finally, while it was acknowledged that hospitals

minimum critical steps are that will improve outcome and/or employing agencies are responsible for assessing

from cardiopulmonary arrests. the competency of individuals, Lhere was a very strong

The complex ratios and numbers utilized in BLS train- sentiment that course completion cards should continue

ing also were discussed. It was suggested that all ratios to be issued by agencies conducting BLS courses.

should be simplified and made universal for adult and

pediatric populations. However, no physiologic or educa- RESEARCH INITIATIVES

tional science was presented that would justify this rec-

A number of research initiatives were identified during

ommendation at this time.

this panel discussion. There is an obvious need to study

There was agreement teat flexible approaches to educa-

and evaluate what teaching strategies are the most effec-

tion in terms of getting out of the classroom, moving

tive for specific targeted populations. There is a need to

into the home (with public service announcements),

further quantify specific barriers to learning and perform-

videotapes, and situation-based exercises are ideal supple-

ing CPR. Included in this should be an evaluation of the

mental approaches to the BLS program. Cautions were

complex numbers and ratios included in a CPR program

expressed regarding too much of a compromise in prac-

in comparison to a more simplified model. There is a need

tice time. Individuals must spend time practicing their

to clearly define the minimum number of critical steps

psychomotor skills so that they will remember the critical

that will lead to improving outcome from cardiac arrest.

steps and actions required to help a loved one in the event

Finally, there should be a study of testing versus evalua-

of a real emergency.

tion and its impact on knowledge and skills retention.

The major area of controversy in the educational panel

revolved around the issues of testing and evaluation. All

individuals agreed that course participants should be eval- REFERENCES

1. Logan FA: Fundamentalsof Learning and Motivation, ed 2. Dubuque, Iowa, William C Brown

uated and provided with better feedback of knowledge Co, Publishers, 1976.

and skit1 acquisition. There was a strong agreement that

2. Maslow A: Educationalimplications of humanistic psychologies.HarvardEducatien Review

the problem learner should be identified earlier and reme- 1968;38:685.

diated tirelessly. However, it was at this point that the 3. RogersC: Freedomto Learn. Columbus, ONe, E Merrill Publishing, 1969.

agreement stopped. It is recommended that formal testing 4. AndersonJ: TheArchitecture of Cognition. Cambridge,Massachusetts,Harvard Press,1983.

for "pass" or "fail" be deleted from layperson BLS 5. Moss AJ, Geldstein S: The prehespital phaseof acute myocardial infarction. Circulation

programs. Some individuals felt that testing should be 1970;41:737-742.

optional for lay individuals. Others felt that by deleting 0. Hawks SR: "The Impactof a Supplemental BystanderEducationalUnit on the Emergency

Helping Behaviorof CollegeStudents" (doctoraldissertation). Salt LakeCity, Utah, Brigham

testing, the quality of the educational effort in the lay BLS Young University, 1990.

programs would be compromised severely. 7. He MT, EisenbergMS, Li~in PE, et al: Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking

There was agreement that testing should remain a key medical care: The effect of public education.Ann EmergMod1989;18:727-731.

component for health care professionals and instructors in 8. AlonzoAA: The impact of the family and lay others on care-seekingduring life-threatening

the BLS program. In support of testing for health care pro episodes of suspectedcoronary artery disease. Sec Sei Med 1986;22:1297-1311.

FEBRUARY 1993 22:2 PART 2 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 4 73 2 07

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Flint et al

9. Dracup K, Moser DK: Treatment-seekingbehavio(amongthose with symptomsand signs of 26. Braun P, Reltman N, Florin A: Closed-chestcardiac resuscitation. Problemsin the training of

acute myocardial infarction, in Proceedingsof the National Heart, Lung, and BIood Institute laymen in volunteer rescuesquads. N Engl J Mod 1965;272:1-6.

Symposium on Rapid Identification and Treatmentof Acute Myocardial Infarction. Washington, 27. Mandel LP, Cobb LA, Weaver WD: CPRtraining for patients' families: Do physicians

DC, US Dept of Health and Human Services, 1991, p 25-45. recommend it? Am J Public Health I987;77:727-728.

10. SackmaryB, Wilson EM: Consumerdecision processesin emergencymedical situations. 28. PaneG, Salness KA: A surveyof participants in a mass CPRtraining course.Ann EmergMed

Journal of Ambulatory Care Marketing 1987;1:17-30. 1987;16:1112-1116.

11. Clark LT, BellamVS, FeldmanJG: Determinantsof prehospital delay in inner city patients 29. Mande[ LP, Cobb LA: CPRtraining in the community.Ann ErnergMed1985;14:669-671.

with symptomsof acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1989;80:11-637.

30. Geldberg RJ, GoreJM, Love DG, et al: LaypersonCPT:Are we training the right people?Ann

12. Long H: Adult Learning, Researchand Practice. New York, Cambridge,1983. Emerg Med 1984;13:701004.

13. Tough A: TheAdult's Learning Projects. Toronto,Ontario, Institute for Studies in Education, 31. Hoh MT: Delays in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: An overview. Heart Lung

1987. 1991;20:556-56B.

14. Knowles M: The Modem Practiceof Adult Education: FromPedagogyto Andragogy. Chicago, 32. Dracup K, GuzyPM, Taylor SE, et ah Cardiopulmoaaryresuscitation(CPR)training.

Association Press,1980. Consequencesfor family membersof high-risk cardiac patients. Arch Intern Med1986;146:1757-

15. Thorndike E: Adult Learning. New York, MacMillan, 1928. 1761.

16. Dreyfus14,DreyfusS: The Mind OverMachine. New York, The New York Free Press, 1986. 33. Sigsbee MS, GedenEA: Effectsof anxiety on family membersof patients with cardiac

17. BennerP: FromNovice to Expert. 1986 IBID.Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley, 1986. disease learning cardiopulmonaryresuscitation. HeartLung 1990;19:662-665.

18. FriesenL, Stotts NA: Retentionof basic cardiac life support content:The effect of ~ o 34. Dracup K, HeaneyDM, Taylor SE, et ah Can family membersof high risk cardiac patients

teaching methods(research).J Nuts Educ1984;23(5):184-191. learn cardiopulmonaryresuscitation?Arch Intern Med1989;149:61-64.

19. VanderschmidtH, BumapTK, Thwaites JK: Evaluationof a cardfopulmonaryresuscitation 35. McCormackAP, DamonSK, EisenbergMS: Disagreeablephysical characteristicsaffecting

course for secondaryschool retention study. Mad Care 1976;14(2):181-184. bystander CPR.Ann EmergMed 1989;18:283-285.

20. CurryL, GassD: Effectsof CPRtraining: Participantcompetenceand patient outcomes. 36. OrnateJP, Hallagan LF, McMahan SB, at ah Attitudes of BCLSinstructorsabout mouth4o-

Proceedings of the Annual Conferenceon ResidentMedical Education 1987;23:243-248. mouth resuscitationduring the AIDS epidemic.Ann EmergMad 1990;19:151-156.

21. VanKalmthoutP, Speth P, Rutten J, et el: Evaluationof lay skills in cardiopulmonary 37. Mendel LP, Scott CS: A surveyof CPRtraining in three cities (unpublished).

resuscitation. Br Heart J 1985;53:562-566. 38. KayeW, Rallis S, Mancini M, et ah The problem of poor retention of cardiopulmonary

22. Weaver FJ, RamirezAG, DorfmanSB, et ah Traineesretention of cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills may lie with the instructors, not the learneror the curriculum. Resuscitation

resuscitation: How quickly they forget. JAMA 1979;241:901-903. 1991;21:67-68.

23. TweedW, Wilson E, Isfeld B: Retentionof cardiopulmonaryresuscitation skills after initial

overtraining. Crit Care Mad 1980;8:651-653. A d d r e s s for reprints:

24. SeamanJE, GreeneBF,Watson-PerczelM: A behaviorsystemfor assessing and training Loring S Flint, Jr, MD

cardiopulmonary resuscitationskills among emerging medical technicians. JApplBehavAnal

1986;19:125-135. Baystate Medical Center

25. Martin W, LoomisJ. Lloyd C: CPRskills: Achievementand retention under stringent and 140 High Street

relaxed criteria. Am J Public Health 1883;73:1310-1312. Springfield, Massachusetts 01199

208/ 474 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 22:2 PART 2 FEBRUARY 1993

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Health Insurance in Switzerland ETHDocumento57 pagineHealth Insurance in Switzerland ETHguzman87Nessuna valutazione finora

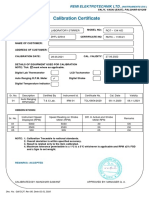

- Calibration CertificateDocumento1 paginaCalibration CertificateSales GoldClassNessuna valutazione finora

- Enerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23Documento15 pagineEnerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23AlokNessuna valutazione finora

- Fernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Documento7 pagineFernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNessuna valutazione finora

- Brochure Ref 670Documento4 pagineBrochure Ref 670veerabossNessuna valutazione finora

- What Caused The Slave Trade Ruth LingardDocumento17 pagineWhat Caused The Slave Trade Ruth LingardmahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hayashi Q Econometica 82Documento16 pagineHayashi Q Econometica 82Franco VenesiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 18 - PPAG-100-HD-C-001 - s018 (VBA03C013) - 0 PDFDocumento1 pagina18 - PPAG-100-HD-C-001 - s018 (VBA03C013) - 0 PDFSantiago GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation On Indian Constitutional LawDocumento6 pagineDissertation On Indian Constitutional LawCustomPaperWritingAnnArbor100% (1)

- Recommended Practices For Developing An Industrial Control Systems Cybersecurity Incident Response CapabilityDocumento49 pagineRecommended Practices For Developing An Industrial Control Systems Cybersecurity Incident Response CapabilityJohn DavisonNessuna valutazione finora

- Notifier AMPS 24 AMPS 24E Addressable Power SupplyDocumento44 pagineNotifier AMPS 24 AMPS 24E Addressable Power SupplyMiguel Angel Guzman ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- P394 WindActions PDFDocumento32 pagineP394 WindActions PDFzhiyiseowNessuna valutazione finora

- DesalinationDocumento4 pagineDesalinationsivasu1980aNessuna valutazione finora

- Income Statement, Its Elements, Usefulness and LimitationsDocumento5 pagineIncome Statement, Its Elements, Usefulness and LimitationsDipika tasfannum salamNessuna valutazione finora

- SEERS Medical ST3566 ManualDocumento24 pagineSEERS Medical ST3566 ManualAlexandra JanicNessuna valutazione finora

- Privacy: Based On Slides Prepared by Cyndi Chie, Sarah Frye and Sharon Gray. Fifth Edition Updated by Timothy HenryDocumento50 paginePrivacy: Based On Slides Prepared by Cyndi Chie, Sarah Frye and Sharon Gray. Fifth Edition Updated by Timothy HenryAbid KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Motor DrivesDocumento24 pagineIntroduction To Motor Drivessukhbat sodnomdorjNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARDocumento2 pagineG.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARTheodore DolarNessuna valutazione finora

- PLT Lecture NotesDocumento5 paginePLT Lecture NotesRamzi AbdochNessuna valutazione finora

- Resume Jameel 22Documento3 pagineResume Jameel 22sandeep sandyNessuna valutazione finora

- 3412C EMCP II For PEEC Engines Electrical System: Ac Panel DC PanelDocumento4 pagine3412C EMCP II For PEEC Engines Electrical System: Ac Panel DC PanelFrancisco Wilson Bezerra FranciscoNessuna valutazione finora

- Amerisolar AS 7M144 HC Module Specification - CompressedDocumento2 pagineAmerisolar AS 7M144 HC Module Specification - CompressedMarcus AlbaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Extent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home EconomicsDocumento47 pagineExtent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home Economicschukwu solomon75% (4)

- Ikea AnalysisDocumento33 pagineIkea AnalysisVinod BridglalsinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Environment Analysis - Saudi ArabiaDocumento24 pagineBusiness Environment Analysis - Saudi ArabiaAmlan JenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Annual BudgetDocumento4 pagineSample Annual BudgetMary Ann B. GabucanNessuna valutazione finora

- TSB 120Documento7 pagineTSB 120patelpiyushbNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab Session 7: Load Flow Analysis Ofa Power System Using Gauss Seidel Method in MatlabDocumento7 pagineLab Session 7: Load Flow Analysis Ofa Power System Using Gauss Seidel Method in MatlabHayat AnsariNessuna valutazione finora

- Cic Tips Part 1&2Documento27 pagineCic Tips Part 1&2Yousef AlalawiNessuna valutazione finora

- PeopleSoft Application Engine Program PDFDocumento17 paginePeopleSoft Application Engine Program PDFSaurabh MehtaNessuna valutazione finora