Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Confounders Among Nondrinking and Moderate-Drinking U.S. Adults

Caricato da

bavaneshDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Confounders Among Nondrinking and Moderate-Drinking U.S. Adults

Caricato da

bavaneshCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Brief Reports

Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Confounders Among

Nondrinking and Moderate-Drinking U.S. Adults

Timothy S. Naimi, MD, MPH, David W. Brown, MSPH, MS, Robert D. Brewer, MD, MSPH,

Wayne H. Giles, MD, MS, George Mensah, MD, Mary K. Serdula, MD, MPH, Ali H. Mokdad, PhD,

Daniel W. Hungerford, DrPH, James Lando, MD, MPH, Shapur Naimi, MD, Donna F. Stroup, PhD, MSc

Background: Studies suggest that moderate drinkers have lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality

than nondrinkers and heavy drinkers, but there have been no randomized trials on this

topic. Although most observational studies control for major cardiac risk factors, CVD is

independently associated with other factors that could explain the CVD benefits ascribed

to moderate drinking.

Methods: Data from the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a population-based

telephone survey of U.S. adults, was used to assess the prevalence of CVD risk factors and

potential confounders among moderate drinkers and nondrinkers. Moderate drinkers

were defined as men who drank an average of two drinks per day or fewer, or women who

drank one drink or fewer per day.

Results: After adjusting for age and gender, nondrinkers were more likely to have characteristics

associated with increased CVD mortality in terms of demographic factors, social factors,

behavioral factors, access to health care, and health-related conditions. Of the 30

CVD-associated factors or groups of factors that we assessed, 27 (90%) were significantly

more prevalent among nondrinkers. Among factors with multiple categories (e.g., body

weight), those in higher-risk groups were progressively more likely to be nondrinkers.

Removing those with poor health status or a history of CVD did not affect the results.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that some or all of the apparent protective effect of moderate

alcohol consumption on CVD may be due to residual or unmeasured confounding. Given

their limitations, nonrandomized studies about the health effects of moderate drinking

should be interpreted with caution, particularly since excessive alcohol consumption is a

leading health hazard in the United States.

(Am J Prev Med 2005;28(4):369 –373) © 2005 American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Introduction including breast cancer. And finally, more than 20% of

“moderate” drinkers in the U.S. general population re-

W

hen viewed prospectively, the initiation of alco-

port binge drinking (drinking 5⫹ drinks at one time),

hol consumption entails risk. In the U.S., about

putting them at risk for injuries, violence, and other

30% of those who drink alcohol do so exces-

sively, and excessive drinking is the third leading actual adverse health and social outcomes.4

cause of death in the United States, killing 75,000 persons While moderate drinkers in most, but not all, study

annually.1,3,4 Furthermore, even those drinking at “mod- populations appear to have a reduced risk of death

erate” levels (as defined by their average daily consump- from cardiovascular disease (CVD), unmeasured or

tion) are at increased risk of death from certain causes, residual confounding5–12 could complicate the inter-

pretation of these studies, especially since the strength

of the association between moderate drinking and CVD

From the Emerging Investigations and Analytic Methods Branch

(Brewer, Brown, Giles, T Naimi), the Behavioral Surveillance Branch outcomes is modest relative to other risk factors.13 It is

(Mokdad), the Cardiovascular Disease Branch (Mensah), Division of important to clarify whether CVD benefits are being

Adult and Community Health, the Nutrition Branch, Division of

Physical Activity and Nutrition (Serdula), and the Office of the

misattributed to moderate drinking, since initiating or

Director (Lando, Stroup), National Center for Chronic Disease increasing alcohol consumption also carries risk. The

Prevention and Health Promotion, the Center for Injury Prevention purpose of this study was to compare the prevalence of

and Control (Hungerford), Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion, Atlanta, GA; and the Division of Cardiology, Tufts–New England CVD risk factors and potential confounders among

Medical Center, Boston, MA (S Naimi) nondrinkers and moderate drinkers using data from

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Timothy Naimi, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Hwy NE,

MS K-67, Atlanta GA 30341. E-mail: tbn7@cdc.gov. (BRFSS). To date, there have been no randomized

Am J Prev Med 2005;28(4) 0749-3797/05/$–see front matter 369

© 2005 American Journal of Preventive Medicine • Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011

clinical trials examining the relationship between mod- erate drinkers; only male gender and smoking were

erate alcohol consumption and any mortality endpoint. significantly more associated with moderate drinking.

This was true before and after adjusting for age and

gender. Examples of factors more commonly associated

Methods

with nondrinking status included being older and

The BRFSS is a population-based cross-sectional telephone nonwhite, being widowed or never married, having less

health survey of U.S. adults aged ⱖ18 years conducted by state education and income, lacking access to health care or

and territorial health departments with funding and technical preventive health services, having comorbid health

assistance provided by the Centers for Disease Control and conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, having

Prevention.14,15 In 2003, there were 250,496 respondents, and

lower levels of mental well-being, being more likely to

the response rate was 54%. Average daily alcohol consumption

require medical equipment, having worse general

was calculated by multiplying the number of drinks typically

consumed by the fraction of days that alcohol was consumed

health, and having a higher CVD risk score.

(i.e., the quantity–frequency method). Nondrinkers were de- For factors in which there were multiple risk catego-

fined as those who did not drink alcohol during the past 30 days. ries, there was a graded relationship between increas-

Moderate drinkers were defined as male drinkers who con- ing levels of risk and an increased likelihood of being a

sumed an average of two drinks per day or less, or female nondrinker (Table 1). For example, those with progres-

drinkers who consumed an average of one drink per day or sively lower levels of income, education, physical activ-

less.16 Therefore, moderate drinkers included what some inves- ity, and overall health status, or those with higher BMIs

tigators refer to as light or occasional drinkers. or higher CVD risk scores, were progressively more

Two analyses compared nondrinkers to moderate drinkers; likely to be nondrinkers than moderate drinkers.

those who drank in excess of moderate levels were excluded. In Excluding those with either poor health or a history

the first analysis (reported in Table 1), the entire national

of CVD from the analysis did not substantially affect the

sample was used to compare nondrinkers (n ⫽116,841) to

results. Of the 30 factors assessed, 26 (87%) were still

moderate drinkers (n ⫽118,889). In the second analysis, data

from all 25 states that included questions about CVD history significantly more common among nondrinkers than

were analyzed after excluding those with a history of CVD moderate drinkers; only male gender and current

(coronary disease, previous heart attack or stroke) or those with smoking were significantly more common among mod-

poor health. This analysis included 45,771 nondrinkers and erate drinkers (data not shown). Examples of factors

45,170 moderate drinkers. Those with poor health were ex- that were significantly associated with nondrinking

cluded because they may stop drinking (i.e., become de facto status included being older and nonwhite; being unem-

nondrinkers) and “contaminate” the nondrinking group. Those ployed (AOR⫽1.28); having an income of ⬍$25,000

with a history of CVD were excluded to be sure that the (AOR⫽2.85); lacking health insurance (AOR⫽1.50);

CVD-associated factors preceded the development of CVD. having diabetes (AOR⫽2.20); reporting more un-

The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) that a particular factor was healthy mental days (AOR⫽1.20); requiring medical

more likely to be associated with nondrinkers than moderate

equipment (AOR⫽1.97); and having a CVD score of

drinkers was calculated. Odds ratios were adjusted for age

(continuous) and gender. For factors in which multiple risk

ⱖ5 (AOR⫽2.91).

categories were assessed, the referent group was the group with

the lowest CVD risk based on the medical literature, and the Discussion

adjusted odds described the likelihood of being a nondrinker

for a particular risk category compared to the likelihood of The purpose of this population-based study was to assess

being a nondrinker in the referent category. the prevalence of known CVD risk factors and potential

Self-reported CVD risk factors and/or confounders were confounders among nondrinkers and moderate drinkers

divided into five domains: demographic factors (e.g., age); in order to determine if these factors could account for at

social factors (e.g., marital status, income); behavioral factors least some of the apparent protective effect of moderate

(e.g., physical activity); health access (e.g., lack of insurance); drinking on CVD. In sum, it appears that moderate

and health conditions (e.g., weight status, mental well-being).

drinkers have many social and lifestyle characteristics that

The CVD risk score was calculated by summing the following

favor their survival over non-drinkers, and few (if any) of

risk factors (each factor was worth 1 point): age (ⱖ45 years

for men or ⱖ55 years for women), current smoking, obesity

these differences are likely due to alcohol consumption

(body mass index [BMI]ⱖ30 kg/m2), diabetes, physical inac- itself. Overall, 90% of risk factors were significantly more

tivity, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Dental extractions common among nondrinkers; only 2 risk factors were

due to infection/periodontal disease were analyzed because more common among moderate drinkers. Furthermore,

oral hygiene and dental infections are independently associ- among factors with multiple risk categories, higher levels

ated with CVD.17 of risk (e.g., the highest BMI category) were progressively

more strongly associated with nondrinking status. The

findings were similar before and after adjusting for age

Results

and gender, and after excluding those with poor health or

Of the individual factors, 27 of 30 (90%) were signifi- a history of CVD from the analysis. These results suggest

cantly more prevalent among nondrinkers than mod- that residual confounding or unmeasured effect modifi-

370 American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 28, Number 4

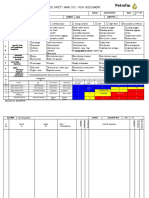

Table 1. Distribution of selected cardiovascular risk factors and potential confounding factors by drinking status, and the

adjusted relative odds of being a nondrinker among people with those factors, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

survey, 2003 (continued)

Nondrinkers Moderate drinkers Adjusteda relative

(%, SE) (%, SE) odds (95% CI) of

Risk factor/confounder (n ⴝ 116,841) (n ⴝ 118,889) being a nondrinker

DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS

Age (years)

18–34 27.2(0.28) 32.6(0.27) —

35–54 36.1 (0.27) 42.1 (0.27) —

55–64 14.2 (0.18) 12.4 (0.16) —

ⱖ65 22.5 (0.22) 12.9 (0.17) —

Gender (% men) 39.1 (0.29) 55.0 (0.27) —

Race/ethnicity

White, NH 66.0 (0.29) 74.7 (0.28) 1.00 (referent)

Black, NH 11.6 (0.19) 7.2 (0.15) 1.95 (1.84–2.07)

Hispanic 14.7 (0.26) 11.7 (0.24) 1.66 (1.22–1.52)

Asian 3.1 (0.14) 2.3 (0.11) 1.87 (1.64–2.14)

American Indian/Alaska Native, NH 1.7 (0.07) 1.4 (0.06) 1.51 (1.35–1.70)

Other 2.8 (0.10) 2.7 (0.10) 1.36 (1.22–1.52)

SOCIAL FACTORS

Marital status

Married/unmarried couple 61.7 (0.28) 65.4 (0.26) 1.00 (referent)

Divorced/separated 11.9 (0.17) 11.1 (0.15) 1.05 (1.00–1.09)

Widowed 10.1 (0.14) 4.6 (0.10) 1.43 (1.34–1.52)

Never married 16.4 (0.24) 18.9 (0.24) 1.16 (1.11–1.22)

Unemployed 6.0 (0.16) 5.4 (0.14) 1.29 (1.20–1.40)

Education

College graduate 22.7 (0.23) 38.8 (0.26) 1.00 (referent)

Some college 25.7 (0.24) 28.0 (0.25) 1.56 (1.50–1.62)

High school graduate 34.6 (0.27) 26.1 (0.25) 2.23 (2.14–2.32)

⬍High school 17.1 (0.23) 7.1 (0.17) 4.06 (3.81–4.32)

Income

ⱖ$50,000 28.7 (0.28) 49.3 (0.29) 1.00 (referent)

$25,000–$49,999 32.5 (0.29) 29.8 (0.26) 1.83 (1.75–1.91)

⬍$25,000 38.8 (0.30) 20.9 (0.25) 2.96 (2.84–3.10)

BEHAVIORAL FACTORS

No “leisure-time” physical activity 31.9 (0.26) 17.7 (0.22) 2.02 (1.94–2.09)

Overall physical activity level

Recommended 40.6 (0.29) 49.7 (0.28) 1.00 (referent)

Insufficient 38.0 (0.28) 40.2 (0.27) 1.11 (1.07–1.15)

Inactive 21.4 (0.24) 10.1 (0.17) 2.31 (2.19–2.42)

Smoking status

Never smoker 59.0 (0.28) 50.9 (0.27) 1.00 (referent)

Former smoker 22.8 (0.23) 26.7 (0.24) 0.68 (0.66–0.71)

Current smoker 18.2 (0.22) 22.4 (0.23) 0.76 (0.73–0.79)

Diet—vegetables (<5 servings/day) 75.1 (0.25) 77.3 (0.23) 1.00 (0.96–1.04)

HEALTHCARE ACCESS

No health insurance 16.0 (0.23) 13.5 (0.21) 1.49 (1.42–1.57)

No personal doctor 18.1 (0.25) 20.9 (0.25) 1.07 (1.02–1.12)

Couldn’t see doctor due to cost 14.0 (0.20) 11.2 (0.19) 1.35 (1.28–1.42)

No influenza shot (age >50) 46.4 (0.38) 48.0 (0.42) 1.14 (1.08–1.19)

No cholesterol screening 25.0 (0.27) 25.4 (0.26) 1.26 (1.21–1.32)

No colorectal cancer screening 41.0 (0.81) 36.4 (0.86) 1.34 (1.21–1.49)

(age >50)

HEALTH CONDITIONS

Diabetes 11.4 (0.17) 4.6 (0.11) 2.37 (2.23–2.52)

Hypertension 31.2 (0.25) 21.7 (0.22) 1.44 (1.39–1.49)

Body mass index (kg/m2)

⬍18.0 1.5 (0.08) 1.0 (0.06) 1.69 (1.43–2.00)

18.0–24.9 36.4 (0.28) 41.1 (0.27) 1.00 (referent)

25.0–29.9 34.9 (0.28) 38.0 (0.27) 1.12 (1.08–1.16)

30.0–34.9 17.0 (0.22) 14.0 (0.20) 1.44 (1.37–1.51)

35.0–39.9 6.5 (0.14) 4.1 (0.11) 1.82 (1.69–1.96)

ⱖ40.0 3.8 (0.11) 1.9 (0.07) 2.28 (2.06–2.51)

High blood cholesterol 36.1 (0.29) 32.4 (0.28) 1.05 (1.01–1.09)

(continued on next page)

Am J Prev Med 2005;28(4) 371

Table 1. Distribution of selected cardiovascular risk factors and potential confounding factors by drinking status, and the

adjusted relative odds of being a nondrinker among people with those factors, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

survey, 2003

Nondrinkers Moderate drinkers Adjusteda relative

(%, SE) (%, SE) odds (95% CI) of

Risk factor/confounder (n ⴝ 116,841) (n ⴝ 118,889) being a nondrinker

HEALTH CONDITIONS (continued)

Current asthma 8.7 (0.16) 6.9 (0.14) 1.19 (1.13–1.27)

Any teeth removed (10 states)b 54.8 (0.63) 40.7 (0.54) 1.57 (1.46–1.68)

Arthritis 32.3 (0.25) 23.5 (0.22) 1.24 (1.19–1.28)

General health status

Excellent 17.3 (0.22) 24.7 (0.23) 1.00 (referent)

Very good 28.3 (0.26) 37.4 (0.26) 1.05 (1.01–1.10)

Good 31.2 (0.26) 28.0 (0.25) 1.53 (1.47–1.61)

Fair 15.9 (0.21) 8.0 (0.16) 2.57 (2.42–2.73)

Poor 7.3 (0.14) 2.0 (0.07) 4.58 (4.18–5.02)

>14 unhealthy physical days 14.1 (0.20) 6.2 (0.13) 2.23 (2.12–2.36)

>14 unhealthy mental days 10.6 (0.18) 8.0 (0.15) 1.32 (1.25–1.40)

>14 activity limitation days 16.3 (0.29) 7.5 (0.20) 2.15 (2.00–2.32)

Use medical equipment 9.4 (0.15) 3.9 (0.10) 2.13 (2.00–2.28)

CVD risk scorec

0 23.5 (0.26) 29.0 (0.25) 1.00 (referent)

1 25.1 (0.25) 31.1 (0.26) 1.00 (0.95–1.05)

2 21.4 (0.23) 21.0 (0.22) 1.24 (1.18–1.31)

3 15.8 (0.19) 12.0 (0.17) 1.58 (1.49–1.67)

4 9.2 (0.15) 5.0 (0.12) 2.12 (1.98–2.28)

ⱖ5 5.0 (0.12) 1.9 (0.07) 3.19 (2.89–3.52)

Note: For factors in which multiple categories were assessed, the referent group was the lowest risk group. Example interpretation for education:

compared to those with a college education (the referent group), those with less than a high school education had 4.06 times the odds of being

nondrinkers, after adjusting for age and gender. An identical analysis was performed after excluding those with either poor health or a history

of CVD (see results).

a

The odds ratios and 95% CIs were adjusted for age (continuous) and gender.

b

Refers to tooth removal due to gum disease or periodontal infection.

c

The CVD risk score was calculated by summing the following: age (ⱖ45 for men; ⱖ55 for women); smoking; obesity (body mass index ⱖ30);

diabetes; physical inactivity; hypertension; and high cholesterol.

CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NH, non-Hispanic; SE, standard error.

cation would bias observational studies in favor of moder- remove sick quitters,5 did not substantially affect the

ate drinkers. results of the analysis. Although it is possible that

In studies of moderate drinking and CVD, it can be alcohol-related nonresponse could bias the study, non-

difficult to control for confounding because CVD is response is typically highest among those drinking in

multifactoral, and because moderate drinking has a rela- excess of moderate levels, and these individuals were

tively small effect size relative to other risk factors. Fur- excluded from our analyses since we were only studying

thermore, while most studies control for some CVD risk nondrinkers and moderate drinkers. And finally, al-

factors, there are emerging factors that are also indepen- though information on risk factors and health condi-

dently associated with CVD. Examples of such factors tions was based on self-report, it seems likely that

include poverty, psychological characteristics, newly dis- nondrinkers (who had less education and healthcare

covered CVD risk factors (e.g., homocysteine, C-reactive access) would actually be less likely to be aware of their

protein, multiple adverse childhood experiences), and prevalent health conditions and risk factors, suggesting

as-yet unidentified factors.13,18 –20 Finally, although com- that the associations we observed between nondrinking

binations of CVD-related factors (e.g., diabetes coupled status and CVD risk factors were conservative.

with lack of health insurance) are synergistic in terms of Widespread scientific and public perceptions about the

risk,21–24 it is not generally practical or possible to assess all benefits of moderate drinking 27–32 may carry public

such combinations for effect modification and most stud- health risk since approximately 30% of current drinkers

ies do not address effect modification at all. drink excessively,4 and excessive drinking accounts for

This study did not compare moderate drinkers to 75,000 deaths annually in the United States.3 If large

those who never drank alcohol (such analyses are done numbers of nondrinkers begin drinking for their health,

in an effort to remove “sick quitters,”25 but this infor- some initiates will undoubtedly drink excessively and/or

mation was unavailable in BRFSS). However, excluding suffer adverse effects from alcohol. This creates an ethical

sick quitters have not explained observed differences in dilemma for the scientific and public health communi-

CVD outcomes in U.S. studies.26 Furthermore, exclud- ties, particularly in the absence of randomized controlled

ing those in poor health, which is another way to trials about the impact of moderate alcohol consumption

372 American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 28, Number 4

12. Murray RP, Connett JE, Tyas SL, et al. Alcohol volume, drinking pattern,

What This Study Adds . . . and cardiovascular disease morbidity adn mortality: is there a u-shaped

function? Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:242– 8.

Observational studies suggest that moderate 13. Splaver A, Lamas GA, Hennekins CH. Homocysteine and cardiovascular

disease: biological mechanisms, observational epidemiology, and the need

drinking may lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) for randomized trials. Am Heart J 2004;148:34 – 40.

mortality. 14. Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Waller M, et al. Objectives and design of the

Although most studies control for “major” Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Paper presented at American

Statistical Association National Meeting, Dallas TX, 1998.

CVD-associated risks, CVD is independently asso- 15. Nelson DE. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk

ciated with many factors. Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Social Prev Med 2001;46(suppl

In this population-based study, 27/30 (90%) of 1):S3– 42.

16. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and

CVD-associated factors were more prevalent Human Services. Nutrition and your health: dietary guidelines for Ameri-

among nondrinkers than moderate drinkers. cans. 5th ed. Home and Gardening Bulletin 232. Washington DC: U.S.

Furthermore, among factors with multiple risk Government Printing Office, 2000.

17. Mattila KJ, Valtonen VV, Nieminen M, Huttunen JK. Dental infection and

strata, increasing risk was progressively associated the risk of new coronary events: prospective study of patients with docu-

with nondrinking status. mented coronary artery disease. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:588 –92.

These findings suggest that the apparent pro- 18. Cahalin D, Cisin IH, Crossley HM. Demographic and sociological corre-

lates of levels of drinking. In: American drinking practices. New Brunswick

tective effect of moderate drinking may be due to NJ: Rutgers Center on Alcohol Studies, 1969:18 – 64.

confounding. 19. Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, et al. Insights into causal pathways for

ischemic heart disease: and adverse childhood experiences study. Circula-

tion 2004;110:1761– 6.

20. Williams JE, Paton CC, Siegler IC, et al. Anger proneness predicts coronary

artery heart disease risk: prospective analysis from the atherosclerosis risk

in communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 2000;101:2034 –9.

on any mortality endpoint, including all-cause mortality.

21. Parodi PW. The French paradox unmasked: the role of folate. Med

For this and other reasons, current clinical and public Hypotheses 1997;49:313– 8.

health guidelines focus on reducing drinking among 22. Kopp P. Resveratrol, a phytoestrogen found in red wine. A possible

explanation for the conundrum of the French paradox. Eur J Endocrinol

those who drink excessively, and do not recommend that

1998;138:619 –20.

people begin or increase drinking for health reasons.33,34 23. McNamee R. Confounding and confounders. Occup Environ Med

Continued caution is particularly justified since there are 2003;60:227–34.

24. Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology: beyond the basics. Gaithersburg MD:

safe and effective strategies to decrease CVD mortal-

Aspen Publications, 2000.

ity,35–37 many of which are underutilized.38 25. Tsubono Y, Yamada S, Nishino Y, et al. Choice of comparison group in

assessing the health effects of moderate alcohol consumption. JAMA

2001;286:1177– 8.

No financial conflict of interest was reported by the authors of 26. Mukmal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA, et al. Roles of drinking pattern

this paper. and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men. N Engl

J Med 2003;348:109 –18.

27. Rosen M. Drink to this: the evidence is growing: for most people, having

one or two glasses of alcohol every day is healthier than not drinking at all.

References Boston Globe, Health Science section, April 6, 2004, pp. C11, C13.

1. Mokdad AH, Stroup D, Marks JS, Gerberding J. Actual causes of death in 28. Zuger A. The case for drinking (all together now: in moderation!). New

the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238 – 45. York Times, December 31, 2002.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ 29. Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2

alcohol/. Accessed December 10, 2004. diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med 2001;345:790 –7.

3. Stahre M, Brewer RD, Naimi TS, et al. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years 30. Klatsky AL. Drink to your health? Scientific American 2003:75– 81.

of potential life lost due to excessive alcohol use in the U.S. Morb Mortal 31. Raloff J. When drinking helps: sorting out for whom a nip might prove

Wkly Rep 2004;53:866 –70. therapeutic. Sci News 2003;163:155– 6.

4. Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad AH, Denny C, Serdula M, Marks JS. Binge 32. Doyle M. Wine health claims allowed. Sacramento Bee. Available at:

drinking among U.S. adults. JAMA 2003;289:70 –5. www.sacbee.com/content/lifestyle/taste/story/6213819p–7168466c.html.

5. Wannamathee SG, Shaper AG. Alcohol, coronary heart disease and stroke: Accessed April 2, 2003.

an examination of the j-shaped curve. Neuroepidemiology 1998;17:288 –95. 33. US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of

6. Shaper AG, Wannamathee SG. Epidemiological confounders in the rela- Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. Alcoholic Beverages.

tionship between alcohol and cardiovascular disease. In: Paoletti R, Klatsky Available at: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/

AL, Poli A, Zakhari S, eds. Moderate alcohol consumption and cardiovas- pdf/Chapter9.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2005.

cular disease. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2000:105–12. 34. Goldberg IJ, Moska L, Piano MR, Fisher EA. Wine and your heart: a science

7. Criqui MH, Ringel BL. Dies diet or alcohol explain the French paradox? advisory for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, Coun-

Lancet 1994;344:1719 –23. cil on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular

8. Shaper AG, Wannamathee SG. The J-shaped curve and changes in drinking Nursing of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2001;103:472–5.

habit. In: Chadwick DJ, ed. Alcohol and cardiovascular disease. Chichester: 35. National Cholesterol Education Project. The detection, evaluation and

John Wiley and Sons, 1998:173–93. treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III).

9. Criqui M. Do known cardiovascular risk factors mediate the effect of Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3full.pdf. Ac-

alochol on cardiovascular disease? In: Chadwick DJ, ed. Alcohol and cessed June 30, 2003.

cardiovascular diseases. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1998:159 –72. 36. Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease

10. Rehm J, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Average volume of alcohol consump- with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med

tion, patterns of drinking, and all-cause mortality: results form the U.S. 1995;333:1301–7.

National Alcohol Survey. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:64 –71. 37. Wilson K, Gibson N, Willan A, Cook D. Effect of smoking cessation on

11. Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:339 – 44.

among middle-aged men and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 38. Coffield AB, Maciosek MV, McGinnis MJ, et al. Priorities among recom-

1997;337:1705–14. mended clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:1–9.

Am J Prev Med 2005;28(4) 373

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- BI Kertas 1 Percubaan UPSR 2013 Kedah SJKCDocumento9 pagineBI Kertas 1 Percubaan UPSR 2013 Kedah SJKCbavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Peralihan Exam PaperDocumento9 paginePeralihan Exam Paperbavanesh100% (1)

- English Exam Paper for Primary School StudentsDocumento16 pagineEnglish Exam Paper for Primary School Studentsbavanesh100% (2)

- B4dl1e1 PBS English Form 1Documento3 pagineB4dl1e1 PBS English Form 1bavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Around The World LC Ump: Contact UsDocumento9 pagineAround The World LC Ump: Contact UsbavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- House Warming Remove Class ActivityDocumento2 pagineHouse Warming Remove Class ActivitybavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Kelantan B Inggeris + Skema (SPM)Documento34 pagineKelantan B Inggeris + Skema (SPM)bavanesh100% (1)

- Around The World LC Ump: Contact UsDocumento9 pagineAround The World LC Ump: Contact UsbavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Such Skills Include Thinking Creatively, Formulating Abstractions, Analyzing ComplexDocumento5 pagineSuch Skills Include Thinking Creatively, Formulating Abstractions, Analyzing ComplexbavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Such Skills Include Thinking Creatively, Formulating Abstractions, Analyzing ComplexDocumento5 pagineSuch Skills Include Thinking Creatively, Formulating Abstractions, Analyzing ComplexbavaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- UploadDocumento7 pagineUploadAlif algifariNessuna valutazione finora

- Server - Time Store Phoneno Mother - NameDocumento8 pagineServer - Time Store Phoneno Mother - Namekundan_2007kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinic, WINS and Health Accomplishment Report 2022Documento8 pagineClinic, WINS and Health Accomplishment Report 2022Hazeline Rey100% (1)

- Final Review - Medical SociologyDocumento15 pagineFinal Review - Medical SociologyEmilyNessuna valutazione finora

- Longevity British English Teacher Ver2Documento6 pagineLongevity British English Teacher Ver2Anna PerepechaevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gina Burden ReportDocumento122 pagineGina Burden ReportMichael HalimNessuna valutazione finora

- TORCH Infections: ICU NursingDocumento27 pagineTORCH Infections: ICU NursingLouis Carlos Roderos0% (1)

- Jco.2022.40.17 Suppl - Lba6003Documento1 paginaJco.2022.40.17 Suppl - Lba6003Paulo Roberto Zanfolim GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bringing Events Back: Austin-Travis County Covid-19 Safety Guide For Venues & Special EventsDocumento13 pagineBringing Events Back: Austin-Travis County Covid-19 Safety Guide For Venues & Special EventsAnonymous Pb39klJNessuna valutazione finora

- Regulating Genetic Biohacking - ScienceDocumento12 pagineRegulating Genetic Biohacking - ScienceKoop Got Da KeysNessuna valutazione finora

- Minimum Plumbing FacilitiesDocumento6 pagineMinimum Plumbing Facilitiesjeckson magbooNessuna valutazione finora

- Final McqsDocumento11 pagineFinal McqsShaban YasserNessuna valutazione finora

- Demography ScriptDocumento10 pagineDemography ScriptLouise AxalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Proposal - Provision of Clean Water and Public Toilet and Sanitation System For Akropong in Ghana, AfricaDocumento3 pagineProject Proposal - Provision of Clean Water and Public Toilet and Sanitation System For Akropong in Ghana, AfricaRhea Mae Caramonte AmitNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital Infection Check List PDFDocumento30 pagineHospital Infection Check List PDFRamayuNessuna valutazione finora

- (Swamedikasi WHO 2009) PDFDocumento80 pagine(Swamedikasi WHO 2009) PDFTommy Winahyu PuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Monthly Reporting Format - HWCDocumento8 pagineRevised Monthly Reporting Format - HWCChanmari West Sub-Centre50% (2)

- Case Report: Intestinal Obstruction in A Child With Massive AscariasisDocumento4 pagineCase Report: Intestinal Obstruction in A Child With Massive AscariasisWella Vista EdwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Gonorrhea Fact SheetDocumento2 pagineGonorrhea Fact SheetRebecca Richardson0% (1)

- Health Declaration Screening FormDocumento1 paginaHealth Declaration Screening FormfitchNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 26 - Assessing Male Genitalia (Interview Guide)Documento3 pagineChap 26 - Assessing Male Genitalia (Interview Guide)Mary Cielo DomagasNessuna valutazione finora

- Isea Super Plus Public - Activated Sludge Plant - Treatment of Domestic Waste WatersDocumento3 pagineIsea Super Plus Public - Activated Sludge Plant - Treatment of Domestic Waste WatersAG-Metal /Tretman Otpadnih Voda/Wastewater Treatment100% (1)

- 10' Wide Road Sewer Layout PlanDocumento1 pagina10' Wide Road Sewer Layout Plankiran NeedleweaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Sanitation PlanDocumento8 pagineSanitation PlanSai Ram ChanduriNessuna valutazione finora

- Espuma en Lodos ActivadosDocumento4 pagineEspuma en Lodos ActivadosLuisa FernandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Immunization InstructionsDocumento2 pagineImmunization InstructionsAli SadeqiNessuna valutazione finora

- Form Daily Individual Performance Management ChecklistDocumento4 pagineForm Daily Individual Performance Management ChecklistAr JayNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Control StudyDocumento23 pagineCase Control StudySwapna JaswanthNessuna valutazione finora

- Petrofac: Job Safety Analysis / Risk AssessmentDocumento4 paginePetrofac: Job Safety Analysis / Risk Assessmentazer Azer0% (1)

- Nursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor and DeliveryDocumento23 pagineNursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor and DeliveryMarie Ashley CasiaNessuna valutazione finora