Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lecture3 - Magnetism and Electromagnetism PDF

Caricato da

Ocwich FrancisTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lecture3 - Magnetism and Electromagnetism PDF

Caricato da

Ocwich FrancisCopyright:

Formati disponibili

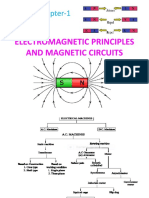

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

3.1 MAGNETIC MATERIALS

Magnetic materials are classified based on the property of permeability as

(a) Diamagnetic materials

(b) Paramagnetic materials

(c) Ferromagnetic materials

Diamagnetic materials

These are materials whose permeability is below unity. They are repelled by a magnet for instance Lead,

gold, mercury, glass, copper

Paramagnetic materials

These are materials whose permeability is above unity. The force of attraction by a magnet towards these

materials is low for instance copper sulphate, platinum, aluminium

Ferromagnetic materials

These are materials whose permeability is thousand of times more than paramagnetic materials. These are

very much attracted for instance iron, nickel, cobalt

3.2 MAGNETIC FIELDS

The lines of magnetic flux have no physical existence; they are purely imaginary and were introduced by

Michael Faraday as a means of visualizing the distribution and density of a magnetic field. It is

important to realize that the magnetic flux permeates the whole of the space occupied by that flux. This

compares with the electric field lines.

3.2.1 Direction of magnetic field

The direction of a magnetic field is taken as that in which the north-seeking pole of a magnet points when

the latter is suspended in the field.

The lines of magnetic flux are assumed to pass through the magnet, emerge from the N pole and return to

the S pole.

3.2.2 Characteristics of lines of magnetic flux

Lines of magnetic flux are assumed to have the following properties

1. The direction of a line of magnetic flux at any point in a non-magnetic medium, such as air, is that

of the north-seeking pole of a compass needle placed at that point.

2. Each line of magnetic flux forms a closed loop, as shown by the dotted lines. This means that a line of

flux emerging from any point at the N-pole end of a magnet passes through the surrounding space back to

the S-pole end and is then assumed to continue through the magnet to the point at which it emerged at the

N-pole end.

3. Lines of magnetic flux never intersect. This follows from the fact that if a compass needle is placed in

a magnetic field, its north-seeking pole will point in one direction only, namely in the direction of the

magnetic flux at that point.

4. Unlike poles attract each other, like poles repel each other

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 1

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

3.2.3 Magnetic field due to an electric current

When a conductor carries an electric current, a magnetic field is produced around that conductor. Thus it

is found that if we look along the conductor and if the current is flowing away from us, as shown by the

cross inside the conductor in Fig. below, the magnetic field has a clockwise direction and the lines of

magnetic flux can be represented by concentric circles around the wire.

The method of deriving this relationship is to grip the conductor with the

right hand, with the thumb outstretched parallel to the conductor and pointing

in the direction of the current; the fingers then point in the direction of the

magnetic flux around the conductor. This is known as the Right-hand screw

rule.

3.2.4 Magnetic field of a solenoid

If a coil is wound on a steel rod, as in Fig. below, and connected to a battery, the steel becomes

magnetized and behaves like a permanent magnet. The magnetic field of the electromagnet is represented

by the dotted lines and its direction by the arrowheads.

The direction of the magnetic field produced by a current in a solenoid

may be deduced by applying either the screw or the grip rule.

If the axis of the screw is placed along that of the solenoid and if the

screw is turned in the direction of the current, it travels in the direction

of the magnetic field inside the solenoid, namely towards the right in

Fig. on the left.

The grip rule can be expressed thus: if the solenoid is gripped with the

right hand, with the fingers pointing in the direction of the current, i.e.

conventional current, then the thumb outstretched parallel to the axis of

the solenoid points in the direction of the magnetic field inside the

solenoid.

3.2.5 Force on a current-carrying conductor

A conductor carrying a current can produce a force on a magnet situated in the vicinity of the conductor.

By Newton’s third law of motion, namely that to every force there must be an equal and opposite force, it

follows that the magnet must exert an equal force on the conductor.

The mechanical force exerted by the conductor always acts in a direction perpendicular to the plane of the

conductor and the magnetic field direction. The direction is given by the Fleming's left-hand rule.

The force on a conductor carrying a current at right angles to a

magnetic field is increased (a) when the current in the conductor is

increased, and (b) when the magnetic field is made stronger by

bringing the magnet nearer to the conductor.

Force on conductor∝current×(flux density)×(length of conductor)

If F is the force on conductor in newtons, I the current through

conductor in amperes and l the length, in metres, of conductor at right angles to magnetic field

F [newtons] ∝ flux density × l [metres] × I [amperes]

The unit of flux density is taken as the density of a magnetic field such that a conductor carrying 1

ampere at right angles to that field has a force of 1 newton per metre acting upon it. This unit is termed a

tesla* (T).

Magnetic flux density Symbol: B Unit: tesla (T)

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 2

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

For a magnetic field having a cross-sectional area of A square metres and a uniform flux density of B

teslas, the total flux in webers (Wb) is represented by Φ (phi).

Magnetic flux Symbol: Φ Unit: weber (Wb)

2

It follows that, Φ [webers] = B [teslas] × A [metres ]

Example 1: A conductor carries a current of 800 A at right angles to a magnetic field having a density of

0.5 T. Calculate the force on the conductor in newtons per metre length.

Example 2: A rectangular coil measuring 200 mm by 100 mm is mounted such that it can be rotated

about the midpoints of the 100 mm sides.

The axis of rotation is at right angles to a magnetic field of uniform flux density 0.05 T. Calculate the flux

in the coil for the following conditions:

(a) the maximum flux through the coil and the position at which it occurs;

(b) the flux through the coil when the 100 mm sides are inclined at 45° to the direction of the flux

3.2.6 Electromagnetic induction

Michael Faraday discovered a method of obtaining an electric current with the aid of magnetic flux i.e.

electromagnetic induction. An electric current could be produced by the movement of magnetic flux

relative to a coil. The magnitude of the induced e.m.f. is proportional to the rate at which the magnetic

flux passed through the coil is varied.

Alternatively, we can say that, when a conductor cuts or is cut by magnetic flux, an e.m.f. is generated in

the conductor and the magnitude of the generated e.m.f. is proportional to the rate at which the conductor

cuts or is cut by the magnetic flux.

There are two methods are available for deducing the direction of the induced or generated e.m.f., namely

(a) Fleming’s right-hand rule

(b) Lenz’s law

Fleming’s right-hand rule

If the first finger of the right hand is pointed in the direction of the

magnetic flux, and if the thumb is pointed in the direction of motion of

the conductor relative to the magnetic field, then the second finger, held

at right angles to both the thumb and the first finger, represents the

direction of the e.m.f.

Lenz’s law

The direction of an induced e.m.f. is always such that it tends to set up a current opposing the motion or

the change of flux responsible for inducing that e.m.f.

Let us consider the application of Lenz’s law to the ring shown above. By applying either the screw or the

grip rule, we find that when S is closed and the battery has the polarity shown, the direction of the

magnetic flux in the ring is clockwise. Consequently, the current in C must be such as to try to produce a

flux in an anticlockwise direction, tending to oppose the growth of the flux due to A, namely the flux

which is responsible for the e.m.f. induced in C. But an anticlockwise flux in the ring would require the

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 3

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

current in C to be passing through the coil from X to Y. Hence, this must also be the direction of the e.m.f.

induced in C

3.2.7 Magnitude of the generated or induced e.m.f

The e.m.f., in volts, generated in a conductor is equal to the rate (in webers per

second) at which the magnetic flux is cutting or being cut by the conductor

Hence the weber may therefore be defined as that magnetic flux which, when cut at a uniform rate by a

conductor in 1 s, generates an e.m.f. of 1 V.

In general, if a conductor cuts or is cut by a flux of dΦ webers in dt seconds, e.m.f. generated in

conductor = dΦ/dt volts

3.2.8 Magnitude of e.m.f. induced in a coil

The induced e.m.f. circulates a current tending to oppose the increase of flux through the coil, hence the

average e.m.f. induced in one turn is Φ/t volts; which is the average rate of change of flux in webers per

second,

and the average e.m.f. induced in coil is NΦ/t volts which is the average rate of change of flux-linkages

per second

Flux linkage Symbol: Ψ (psi) Unit: weber (Wb)

Ψ = NΦ

It follows that instantaneous value of e.m.f., in volts, induced in a coil is the rate of change of flux-

linkages, in weber-turns per second, or

and

Hence we can also define the weber as that magnetic flux which, linking a circuit of one turn, induces in

it an e.m.f. of 1 V when the flux is reduced to zero at a uniform rate in 1 s.

Example 3: A magnetic flux of 400 μWb passing through a coil of 1200 turns is reversed in 0.1 s.

Calculate the average value of the e.m.f. induced in the coil.

3.3 MAGNETIC CIRCUITS

One of the characteristics of lines of magnetic flux is that each line forms a closed loop. For instance, in

Fig. below, the dotted lines represent the flux set up within a ring made of steel.

The complete closed path followed by any group of magnetic flux lines is

referred to as a magnetic circuit. One of the simplest forms of magnetic

circuit is the ring shown where the steel ring provides the space in which the

magnetic flux is created. Most rings are made like anchor rings in that their

cross-section is circular – such a ring is called a toroid

3.3.1 Magnetomotive force and magnetic field strength

In an electric circuit, the current is due to the existence of an electromotive force. By analogy, we may say

that in a magnetic circuit the magnetic flux is due to the existence of a magnetomotive force (m.m.f.)

caused by a current flowing through one or more turns. The value of the m.m.f. is proportional to the

current and to the number of turns, and is descriptively expressed in ampere-turns; but for the purpose of

dimensional analysis, it is expressed in amperes, since the number of turns is dimensionless. Hence the

unit of magnetomotive force is the ampere.

Magnetomotive force Symbol: F Unit: ampere (A)

If a current of I amperes flows through a coil of N turns, as shown in Fig. above, the magnetomotive force

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 4

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

F is the total current linked with the magnetic circuit, namely IN amperes.

If the magnetic circuit is of uniform cross-sectional area, the magnetomotive force per metre length of the

magnetic circuit is termed the magnetic field strength and is represented by the symbol H.

Thus, if the mean length of the magnetic circuit of Fig. above is l metres,

H = IN/l amperes per metre

Magnetic field strength Symbol: H Unit: ampere per metre (A/m)

3.3.2 Permeability of free space or magnetic constant

The ratio B/H is termed the permeability of free space and is represented by the symbol μ0. Thus

Permeability of free space Symbol: μ0 Unit: henry per metre (H/m)

μ0= 4π × 10−7 H/m

Example 4: A coil of 200 turns is wound uniformly over a wooden ring having a mean circumference of

600 mm and a uniform cross-sectional area of 500 mm2. If the current through the coil is 4.0 A, calculate

(a) the magnetic field strength

(b) the flux density

(c) the total flux.

Example 5: Calculate the magnetomotive force required to produce a flux of 0.015 Wb across an airgap

2.5 mm long, having an effective area of 200 cm2.

3.3.3 Relative permeability

This is the ratio of the flux density produced in a material to the flux density produced in a vacuum (or in

a non-magnetic core) by the same magnetic field strength. It is denoted by the symbol μr

From expression B = μ0H for a non-magnetic material; hence, for a material having a relative

permeability μr, B = μ 0 μr H

3.3.4 Reluctance

Let us consider a ferromagnetic ring having a cross-sectional area of A square metres and a mean

circumference of l metres, wound with N turns carrying a current I amperes, then total flux (Φ) = flux

density × area

∴ Φ = BA …...................(i)

and m.m.f. (F) = magnetic field strength × length.

∴ F = Hl …..................(ii)

Dividing equation (i) by (ii), we have

S is the reluctance of the magnetic circuit where

F = ΦS and

Reluctance Symbol: S Unit: ampere per weber (A/Wb)

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 5

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

If the current through a coil having an inductance of 0.5 H is reduced from 5 A to 2 A in 0.05 s, calculate

the mean value of the e.m.f. induced in the coil.

It is useful to compare the calculation of the reluctance of a magnetic circuit with the calculation of the

resistance of an electric circuit. The resistance of a conductor of length l, cross-sectional area A and

resistivity ρ is given by R = ρl/A

Since electrical conductivity σ = 1/ρ, the expression for R can be rewritten as: R = l/σA

This is very similar indeed to equation for the reluctance S, except permeability μ (= μ0μr) replaces σ. For

both electrical and magnetic circuits, increasing the length of the circuit increases the opposition to the

flow of electric current or magnetic flux. Similarly, decreasing the cross-sectional area of the electric or

magnetic circuit decreases the opposition to the flow of electric current or magnetic flux.

3.3.5 Ohm’s law for a magnetic circuit’

F = ΦS can thus be regarded as ‘Ohm’s law for a magnetic circuit’, since the m.m.f. (F ), the total number

of ampere-turns (= NI) acting on the magnetic circuit.

m.m.f. = flux × reluctance

F = ΦS

or

NI = ΦS

It is clear that m.m.f. (F ) is analogous to e.m.f. (E ) and flux (Φ) is analogous to current (I ) in a d.c.

resistive circuit, where e.m.f. = current × resistance

E = IR

The laws of resistors in series or parallel also hold for reluctances. However, a big difference between

electrical resistance R and magnetic reluctance S is that resistance is associated with an energy loss (the

rate is I2R) whereas reluctance is not. Magnetic fluxes take leakage paths whereas electric currents

normally do not.

Example 6: A mild-steel ring having a cross-sectional area of 500 mm 2 and a mean circumference of 400

mm has a coil of 200 turns wound uniformly around it. Given that relative permeability of mild steel is

about 380, calculate:

(a) the reluctance of the ring;

(b) the current required to produce a flux of 800 μWb in the ring.

Example 7: A magnetic circuit comprises three parts in series, each of uniform cross-sectional area

(c.s.a.). They are:

(a) a length of 80 mm and c.s.a. 50 mm2,

(b) a length of 60 mm and c.s.a. 90 mm2,

(c) an airgap of length 0.5 mm and c.s.a. 150 mm2.

A coil of 4000 turns is wound on part (b), and the flux density in the airgap is 0.30 T. Assuming that all

the flux passes through the given circuit, and that the relative permeability μr is 1300, estimate the coil

current to produce such a flux density.

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 6

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

3.4 INDUCTORS

Any circuit in which a change of current is accompanied by a change of flux, and therefore by an induced

e.m.f., is said to be inductive or to possess self-inductance or merely inductance. It is impossible to have

a perfectly non- inductive circuit, i.e. a circuit in which no flux is set up by a current; but for most

purposes a circuit which is not in the form of a coil may be regarded as being practically non-inductive.

The unit of inductance is termed the henry. A circuit has an inductance of1 henry (or 1 H) if an e.m.f. of

1 volt is induced in the circuit when the current varies uniformly at the rate of 1 ampere per second.

If either the inductance or the rate of change of current is doubled, the induced e.m.f. is doubled. Hence

if a circuit has an inductance of L henrys and if the current increases from i 1to i2 amperes in t seconds the

average rate of change of current is i2 − i1/t amperes per second

and average induced e.m.f. is

volts

Self-inductance Symbol: L Unit: henry (H)

Considering instantaneous values, if di = increase of current, in amperes, in time dt seconds, rate of

change of current is di/dt amperes per second and e.m.f. induced in circuit is

Example: If the current through a coil having an inductance of 0.5 H is reduced from 5 A to 2 A in 0.05 s,

calculate the mean value of the e.m.f. induced in the coil.

3.4.1 Types of inductor and inductance

Inductors are generally made to have a fixed value of inductance, but some are

variable. The symbols for fixed and variable inductors are shown below.

Inductance is the ratio of flux-linkages to current, i.e. the flux linking the turns

through which it appears to pass.

Any circuit must comprise at least a single turn, and therefore the current in the

circuit sets up a flux which links the circuit itself. It follows that any circuit has

inductance. However, the inductance can be negligible unless the circuit

includes a coil so that the number of turns ensures high flux-linkage or the

circuit is large enough to permit high flux-linkage.

Inductors always involve coils of conductor wire.

Inductors fall into two categories – those with an air core and those with a

ferromagnetic core. The air core has the advantage that it has a linear B/H

characteristic which means that the inductance L is the same no matter what

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 7

LECTURE THREE : MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM

current is in the coil. However, the relative permeability of air being 1 means

that the values of inductance attained are very low.

The ferromagnetic core produces very much higher values of inductance, but the B/H characteristic is not

linear and therefore the inductance L varies indirectly with the current.

There are also variable inductors in which the core is mounted on a screw so that it can be made to move

in and out of the coil, thus varying the inductance.

3.4.1 Energy storage in an inductor

Lenz's law states that the direction of an induced e.m.f. is always such that it tends to set up a current

opposing the motion or the change of flux responsible for inducing that e.m.f.

Hence if you try to start current flowing in a wire, the current will set up a magnetic field that opposes the

growth of current. It will take more energy than you expect to get the current flowing. This additional

energy isn't lost - it is stored, in the magnetic field established by the current.

Some people find it helpful to think of this as a back e.m.f. opposing the e.m.f. This voltage is

proportional to the rate of change of flux, which in turn is proportional to the rate of change of current.

3.4.2 Chokes

A choke is an inductor used to block higher-frequency alternating current (AC) in an electrical circuit,

while passing lower-frequency or direct current (DC). A choke usually consists of a coil of insulated wire

often wound on a magnetic core

Chokes are divided into three types broad classes

(a) Audio frequency chokes (AFC)

(b) Radio frequency chokes (RFC)

(c) Common-mode choke

Audio frequency and power supply filter chokes

Designed to block audio and power line frequencies while allowing DC to pass. Audio frequency (AF)

chokes usually have ferromagnetic cores to increase their inductance. They are often constructed similarly

to transformers, with laminated iron cores. A major use in the past was in power supplies to produce

direct current (DC), where they were used in conjunction with large electrolytic capacitors as filters to

remove the alternating current (AC) ripple at the output of rectifiers. However, modern electrolytic

capacitors and voltage regulators that remove more power supply ripple than chokes could, have

eliminated heavy, bulky chokes from mains frequency power supplies.

RF chokes

These are designed to block radio frequencies while allowing audio and DC to pass Chokes for higher

frequencies often have iron powder or ferrite cores. A modern form of choke used for eliminating digital

RF noise from lines is the ferrite bead. These are often seen on computer cables.

Common-mode choke

Common-mode chokes, where two coils are wound on a single core, are useful for prevention of

electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI) from power supply lines and

for prevention of malfunctioning of electronic equipment

DEB 115 Introduction to Electrical Engineering for Biomedical 2018/2019 8

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Building Thinking Skills® - Level 1Documento10 pagineBuilding Thinking Skills® - Level 1NelaAlamos50% (8)

- Network Adjustment Report: Project DetailsDocumento5 pagineNetwork Adjustment Report: Project DetailsNeira Melendez MiguelNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Comm Lab Report SignalsDocumento11 pagineData Comm Lab Report SignalsRafiur Rahman ProtikNessuna valutazione finora

- New notesTOPIC 20 MAGNETIC FIELDSDocumento26 pagineNew notesTOPIC 20 MAGNETIC FIELDSnadiamuhorakeye29Nessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetism 29 JULY 2014 Lesson Description: Magnetic Effect of An Electric CurrentDocumento5 pagineElectromagnetism 29 JULY 2014 Lesson Description: Magnetic Effect of An Electric CurrentHNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetism Short NotesDocumento10 pagineElectromagnetism Short Notespadhaai karoNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetism CSEC NotesDocumento10 pagineElectromagnetism CSEC NotesCornflakes ToastedNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetics Part 3Documento5 pagineMagnetics Part 3AnonymousNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic InductionDocumento21 pagineElectromagnetic InductionParth GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 2.lesson1Documento6 pagineModule 2.lesson1Jerald AlvaradoNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic Principles ExplainedDocumento18 pagineElectromagnetic Principles ExplainedTeshale AlemieNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetism and Electricity - 5th WeekDocumento22 pagineMagnetism and Electricity - 5th WeekChamodya KavindaNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrodynamics Gr.11 Notes and QsDocumento7 pagineElectrodynamics Gr.11 Notes and QsSaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effects of CurrentDocumento57 pagineMagnetic Effects of CurrentaijazmonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Machines Electronics 1Documento9 pagineMachines Electronics 1Romeo MougnolNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic CircuitsDocumento38 pagineMagnetic CircuitsHanan KemalNessuna valutazione finora

- CBSE Class 10 Science Chapter on Magnetic Effects of Electric CurrentDocumento13 pagineCBSE Class 10 Science Chapter on Magnetic Effects of Electric CurrentkunalNessuna valutazione finora

- Dow 00068Documento150 pagineDow 00068Kunal Bagade.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit I (Magnetic Field and Circuits - Electromagnetic Force and Torque)Documento43 pagineUnit I (Magnetic Field and Circuits - Electromagnetic Force and Torque)UpasnaNessuna valutazione finora

- MAGNETIC FIELDS AND ELECTROMAGNETIC EFFECTSDocumento34 pagineMAGNETIC FIELDS AND ELECTROMAGNETIC EFFECTSDevNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effects of Ec-Part1Documento6 pagineMagnetic Effects of Ec-Part1Prisoner FFNessuna valutazione finora

- Attachment PHPDocumento7 pagineAttachment PHPKunal Bagade.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Induction and Faraday's LawsDocumento13 pagineMagnetic Induction and Faraday's LawsShara TayonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic Induction NotesDocumento21 pagineElectromagnetic Induction NotesEs ENessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetism and Magnetic FieldsDocumento26 pagineMagnetism and Magnetic FieldsRacknarockNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Circuits and TransformersDocumento10 pagineMagnetic Circuits and TransformersSantosh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 1Documento24 pagineChap 1far remNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Flux and InductanceDocumento26 pagineMagnetic Flux and InductanceRamkesh MeenaNessuna valutazione finora

- EEC 125 Note UpdatedDocumento23 pagineEEC 125 Note UpdatedElijah EmmanuelNessuna valutazione finora

- General Physics II Magnetic FieldsDocumento38 pagineGeneral Physics II Magnetic FieldsDarious PenillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effect of Electric Current Notes Chpt2Documento11 pagineMagnetic Effect of Electric Current Notes Chpt2Sarathrv Rv100% (2)

- Magnetic Field PDFDocumento29 pagineMagnetic Field PDFPuran BistaNessuna valutazione finora

- CH6 Formula SheetDocumento11 pagineCH6 Formula SheetNancy SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effects of Electric CurrentDocumento9 pagineMagnetic Effects of Electric CurrentTajiriMollelNessuna valutazione finora

- Narmin Jamalli (FF) FaradayDocumento16 pagineNarmin Jamalli (FF) FaradayNarmin JamalliNessuna valutazione finora

- ELECTROMAGNETISM EXPLAINEDDocumento12 pagineELECTROMAGNETISM EXPLAINEDMuneer Kaleri75% (4)

- Magnetic Circuits: Chapter # 1Documento35 pagineMagnetic Circuits: Chapter # 1teza maruNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic InductonDocumento12 pagineElectromagnetic InductonAishwarya TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic InductionDocumento13 pagineElectromagnetic InductionRanjit SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics Project HishitaDocumento14 paginePhysics Project HishitaHishita ThakkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Report: (Magnetism)Documento34 pagineWritten Report: (Magnetism)Jasmine DataNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Electrical Machines: South PoleDocumento41 pagineIntroduction To Electrical Machines: South PoleAnonymous LI3ZWNANessuna valutazione finora

- Physics IPDocumento11 paginePhysics IP12 B 5530 AAKANKSH PERYALANessuna valutazione finora

- Lenz's Law ExplainedDocumento12 pagineLenz's Law ExplainedSANJAY RNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetite: Electrical Machines I (Eec 123) Lecture Notes For ND I (Prepared by Engr Aminu A.A.)Documento26 pagineMagnetite: Electrical Machines I (Eec 123) Lecture Notes For ND I (Prepared by Engr Aminu A.A.)Micah AlfredNessuna valutazione finora

- Electromagnetic Induction LecturesDocumento9 pagineElectromagnetic Induction LecturesDoyen DanielNessuna valutazione finora

- CBSE Class 10 Science Magnetic Effects NotesDocumento12 pagineCBSE Class 10 Science Magnetic Effects NotesAkshithNessuna valutazione finora

- ElectromagnetismDocumento45 pagineElectromagnetismNtirnyuy LeenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter-13 Magnetic Effect of CurrentDocumento19 pagineChapter-13 Magnetic Effect of CurrentSuhani GosainNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effect of Electric CurrentDocumento22 pagineMagnetic Effect of Electric CurrentAnurag Tiwari100% (1)

- Phy Topic 2 F4Documento12 paginePhy Topic 2 F4Kandrossy GlassNessuna valutazione finora

- Nagnetic InductionDocumento102 pagineNagnetic InductionAyush ChaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic Effects of Electric Current: AnswersDocumento5 pagineMagnetic Effects of Electric Current: AnswersAyush AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Elect Roma Gneti SM: How Electric Current Produce A Magnetic FieldDocumento8 pagineElect Roma Gneti SM: How Electric Current Produce A Magnetic FieldIsmail MzavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eee 317Documento28 pagineEee 317imma cover100% (1)

- Faraday's & Lenz LawDocumento14 pagineFaraday's & Lenz LawPnDeNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics NotesDocumento85 paginePhysics NotesJfoxx Samuel0% (1)

- 5 Introduction To Electrical Machines Teaching MaterialDocumento289 pagine5 Introduction To Electrical Machines Teaching MaterialELIAS AyeleNessuna valutazione finora

- CBSE Class 10 Science Notes Chapter 13 Magnetic Effects of Electric CurrentDocumento13 pagineCBSE Class 10 Science Notes Chapter 13 Magnetic Effects of Electric Currentdrphysics256Nessuna valutazione finora

- ch4 CL 10Documento6 paginech4 CL 10jaiathihyadNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetism:: The Physics of Allure and RepulsionDocumento34 pagineMagnetism:: The Physics of Allure and RepulsionSam JonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Induced EmfDocumento5 pagineInduced Emftajju_121Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lira Study Centre: Makerere UniversityDocumento1 paginaLira Study Centre: Makerere UniversityOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Assistive Technology For Peoplewith Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)Documento28 pagineAssistive Technology For Peoplewith Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- TB Medicines Order FormDocumento5 pagineTB Medicines Order FormOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Otuke District Service Commission: VaccanciesDocumento1 paginaOtuke District Service Commission: VaccanciesOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- DENTAL EQUIPMENT Notes SNT 11 02 2020Documento27 pagineDENTAL EQUIPMENT Notes SNT 11 02 2020Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Electronic Cough Monitor: Musaab Hassan, Asiel Satti, Azza Hussien, Tarteel Tag El-DinDocumento3 pagineElectronic Cough Monitor: Musaab Hassan, Asiel Satti, Azza Hussien, Tarteel Tag El-DinOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- 2300 International Jobs Email Blast Reaches 24,000 RecruitersDocumento70 pagine2300 International Jobs Email Blast Reaches 24,000 RecruitersOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- 2000 International Development Jobs Apply Online OCTOBER 2021Documento77 pagine2000 International Development Jobs Apply Online OCTOBER 2021Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Assistive Technology For The Deaf-1Documento23 pagineAssistive Technology For The Deaf-1Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- DEB 221 Electro Medical Devices SENT 4 02 2020Documento20 pagineDEB 221 Electro Medical Devices SENT 4 02 2020Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Biomedical Equip PlanningDocumento6 pagineBiomedical Equip PlanningOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture1 - DC Resistance Circuits PDFDocumento5 pagineLecture1 - DC Resistance Circuits PDFOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- DEB 221 Course Work Due 31 03 2020Documento1 paginaDEB 221 Course Work Due 31 03 2020Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Code and Name: Deb 221 Biomedical Equipment IiDocumento2 pagineCourse Code and Name: Deb 221 Biomedical Equipment IiOcwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Deb 221 Course Work Due 10th March 2020Documento1 paginaDeb 221 Course Work Due 10th March 2020Ocwich FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- MOVIE4UDocumento10 pagineMOVIE4USGNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Environmental Science 14th Edition William Cunningham Mary CunninghamDocumento18 pagineTest Bank For Environmental Science 14th Edition William Cunningham Mary CunninghamAndi AnnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Direct Least Square Fitting of Ellipses: Andrew Fitzgibbon, Maurizio Pilu, and Robert B. FisherDocumento5 pagineDirect Least Square Fitting of Ellipses: Andrew Fitzgibbon, Maurizio Pilu, and Robert B. Fisheroctavinavarro8236Nessuna valutazione finora

- Conclusion and RecommendationDocumento6 pagineConclusion and Recommendationapril rose soleraNessuna valutazione finora

- Prof Ed 13 - Episode 1Documento6 pagineProf Ed 13 - Episode 1Apelacion L. VirgilynNessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Reward SystemDocumento17 pagineOrganizational Reward SystemHitendrasinh Zala100% (3)

- Advances in Water Polllution Monitoring and ControlDocumento185 pagineAdvances in Water Polllution Monitoring and Controlantonioheredia100% (1)

- Original PDF Intentional Interviewing and Counseling Facilitating Client Development in A Multicultural Society 9th Edition PDFDocumento42 pagineOriginal PDF Intentional Interviewing and Counseling Facilitating Client Development in A Multicultural Society 9th Edition PDFshawn.hamilton470100% (31)

- SEO-optimized title for English exam documentDocumento5 pagineSEO-optimized title for English exam documentAyu PermataNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Tutorial Pressure Sept19Documento7 pagine2 Tutorial Pressure Sept19hairinnisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Self ReflectionDocumento2 pagineSelf Reflectionapi-575370301Nessuna valutazione finora

- Online Workshop Analisa Gangguan PetirDocumento64 pagineOnline Workshop Analisa Gangguan PetirJumhanter hutagaolNessuna valutazione finora

- Astronomical Distance, Mass and Time ScalesDocumento11 pagineAstronomical Distance, Mass and Time ScalesHARENDRA RANJANNessuna valutazione finora

- WKS 5 Cutting and Welding Drums and TanksDocumento3 pagineWKS 5 Cutting and Welding Drums and TanksKishor KoshyNessuna valutazione finora

- CICLing2011 Manning TaggingDocumento19 pagineCICLing2011 Manning TaggingMuhammad AbrarNessuna valutazione finora

- CAT of MAT1142 Y 2023 Marking GuideDocumento7 pagineCAT of MAT1142 Y 2023 Marking Guidehasa samNessuna valutazione finora

- Dinosaur Lesson by SlidesgoDocumento41 pagineDinosaur Lesson by SlidesgoDonalyn PaderesNessuna valutazione finora

- Eng201 ch7 Accuracy Clarity Conciseness CoherenceDocumento2 pagineEng201 ch7 Accuracy Clarity Conciseness CoherenceAyesha MughalNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Text On The Rule of The Road by A.G. GardinerDocumento2 pagineReading Text On The Rule of The Road by A.G. GardinerSilidNessuna valutazione finora

- Instant Download Ebook PDF Dynamics of Structures 5th Edition by Anil K Chopra PDF ScribdDocumento41 pagineInstant Download Ebook PDF Dynamics of Structures 5th Edition by Anil K Chopra PDF Scribdlisa.vanwagner713100% (44)

- Margaret Hamilton Takes Software Engineering To The Moon and BeyondDocumento5 pagineMargaret Hamilton Takes Software Engineering To The Moon and BeyondAntonio TorizNessuna valutazione finora

- Osman Jayasinghe Chemistry IIDocumento4 pagineOsman Jayasinghe Chemistry IIyasidu rashmikaNessuna valutazione finora

- WW1Documento4 pagineWW1BellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature and Scope of EconomicsDocumento6 pagineNature and Scope of EconomicsRenu AgrawalNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 2 TacheometryDocumento23 pagineModule 2 TacheometryDaniel JimahNessuna valutazione finora

- Unusual and Marvelous MapsDocumento33 pagineUnusual and Marvelous MapsRajarajan100% (1)

- Unit I - UV-vis Spectroscopy IDocumento10 pagineUnit I - UV-vis Spectroscopy IKrishna Prasath S KNessuna valutazione finora