Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Prostate Infection: Acute Bacterial Prostatitis

Caricato da

Zammira MutiaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Prostate Infection: Acute Bacterial Prostatitis

Caricato da

Zammira MutiaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

PROSTATE INFECTION

Acute Bacterial Prostatitis

Acute bacterial prostatitis refers to inflammation of the prostate associated with a UTI. It is

thought that infection results from ascending urethral infection or reflux of infected urine

from the bladder into the prostatic ducts. In response to bacterial invasion, leukocytes

(polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages) are seen

within and surrounding the acini of the prostate. Edema and hyperemia of the prostatic

stroma frequently develop. With prolonged infection, variable degree of necrosis and

abscess formation can occur.

A. PRESENTATION AND FINDINGS

Acute bacterial prostatitis is uncommon in prepubertal boys but frequent affects adult men.

It is the most common urologic diagnosis in men younger than 50 years (Collins et al, 1998).

Patients with acute bacterial prostatitis usually present with an abrupt onset of constitutional

(fever, chills, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, lower back/rectal/perineal pain) and urinary

symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria). They may also present with urinary retention due

to swelling of the prostate. Digital rectal examination reveals tender, enlarged glands that

are irregular and warm. Urinalysis usually demonstrates WBCs and occasionally hematuria.

Serum blood analysis typically demonstrates leukocytosis. Prostate-specific antigen levels

are often elevated. The diagnosis of prostatitis is made with microscopic examination and

culture of the prostatic expressate and culture of urine obtained before and after prostate

massage. In patients with acute prostatitis, fluid from the prostate massage often contains

leukocytes with fat-laden macrophages. However, at the onset of acute prostatitis, prostatic

massage is usually not suggested

because the prostate is quite tender and the massage may lead to bacteremia. Similarly,

urethral catheterization should be avoided. Culture of urine and prostate expressate usually

identifies a single organism, but occasionally, polymicrobial infection may occur. E. coli is the

most common causative organism in patients with acute prostatitis. Other gram-negative

bacteria (Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, and Serratia spp.) and enterococci

are less frequent pathogens. Anaerobic and other gram-positive bacteria are rarely a cause

of acute prostatitis (RO Roberts et al, 1997).

B. RADIOLOGIC IMAGING

Radiologic imaging is rarely indicated in patients with acute prostatitis. Bladder

ultrasonography may be useful in determining the amount of residual urine. Transrectal

ultrasonography is only indicated in patients who do not respond to conventional therapy.

C. MANAGEMENT

Treatment with antibiotics is essential in the management of acute prostatitis. Empiric

therapy directed against gramnegative bacteria and enterococci should be instituted

immediately, while awaiting the culture results. Trimethoprim and fluoroquinolones have

high drug penetration into prostatic tissue and are recommended for 4–6 weeks

(Wagenlehner et al, 2005). The long duration of antibiotic treatment is to allow complete

sterilization of the prostatic tissue to prevent complications such as chronic prostatitis

and abscess formation (Childs, 1992; Nickel, 2000). Patients who have sepsis, are

immunocompromised or in acute urinary retention, or have significant medical comorbidities

would benefit from hospitalization and treatment with parenteral antibiotics. Ampicillin and

an aminoglycoside provide effective therapy against both gram-negative bacteria and

enterococci. Patients with urinary retention secondary to acute prostatitis should be

managed with a suprapubic catheter because transurethral catheterization or

instrumentation is contraindicated.

Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis

In contrast to the acute form, chronic bacterial prostatitis has a more insidious onset,

characterized by relapsing, recurrent UTI caused by the persistence of pathogen in the

prostatic fluid despite antibiotic therapy.

A. PRESENTATION AND FINDINGS

Most patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis typically present with dysuria, urgency,

frequency, nocturia, and low back/perineal pain. These patients usually are afebrile and not

uncommonly have a history of recurrent or relapsing UTI, urethritis, or epididymitis caused

by the same organism (Nickel and Moon, 2005). Others are asymptomatic, but the diagnosis

is made after investigation for bacteriuria. In patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis,

digital rectal examination of the prostate is often normal; occasionally, tenderness, firmness,

or prostatic calculi may be found on examination. Urinalysis demonstrates a variable degree

of WBCs and bacteria in the urine, depending on the extent of the disease. Serum blood

analysis normally does not show any evidence of leukocytosis. Prostate-specific antigen

levels may be elevated. Diagnosis is made after identification of bacteria from prostate

expressate or urine specimen after a prostatic massage, using the 4-cup test (Table 13–8).

The causative organisms are similar to those

of acute bacterial prostatitis. It is currently believed that other gram-positive bacteria,

Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma, and Chlamydia spp. are not causative pathogens in chronic

bacterial prostatitis.

B. RADIOLOGIC IMAGING

Radiologic imaging is rarely indicated in patients with chronic prostatitis. Transrectal

ultrasonography is only indicated if a prostatic abscess is suspected.

C. MANAGEMENT

Antibiotic therapy is similar to that for acute bacterial prostatitis (Bjerklund Johansen et al,

1998). Interestingly, the presence of leukocytes or bacteria in the urine and prostatic

massage does not predict antibiotic response in patients with chronic prostatitis (Nickel et al,

2001). In patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis, the duration of antibiotic therapy may be

3–4 months. Using fluoroquinolones, some patients may respond after 4–6 weeks of

treatment. The addition of an alpha blocker to antibiotic therapy has

been shown to reduce symptom recurrences (Barbalias, Nikiforidis, and Liatsikos, 1998).

Despite maximal therapy, cure is not often achieved due to poor penetration of antibiotic

into prostatic tissue and relative isolation of the bacterial foci within the prostate. When

recurrent episodes of infection occur despite antibiotic therapy, suppressive antibiotic (TMP-

SMX 1 single-strength tablet daily, nitrofurantoin

100 mg daily, or ciprofloxacin 250 mg daily) may be used (Meares, 1987). Transurethral

resection of the prostate has been used to treat patients with refractory disease; however,

the success rate has been variable and this approach is not generally recommended

(Barnes, Hadley, and O’Donoghue, 1982).

Granulomatous Prostatitis

Granulomatous prostatitis is an uncommon form of prostatitis. It can result from bacterial,

viral, or fungal infection, the use of bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy (Rischmann et al,

2000), malacoplakia, or systemic granulomatous diseases affecting the prostate. Two-third

of the cases have no specific cause. There are 2 distinct forms of nonspecific granulomatous

prostatitis: noneosinophilic and eosinophilic. The former represents an abnormal tissue

response to extravasated prostatic fluid (O’Dea, Hunting, and Greene, 1977). The latter is a

more severe, allergic response of the prostate to some unknown antigen.

A. PRESENTATION AND FINDINGS

Patients with granulomatous prostatitis often present acutely, with fever, chills, and

obstructive/irritative voiding symptoms. Some may present with urinary retention. Patients

with eosinophilic granulomatous prostatitis are severely ill and have high fevers. Digital

rectal examination in patients with granulomatous prostatitis demonstrates a hard,

indurated, and fixed prostate, which is difficult to distinguish from prostate carcinoma.

Urinalysis and culture do not show any evidence of bacterial infection. Serum blood analysis

typically demonstrates leukocytosis; marked eosinophilia is often seen in patients with

eosinophilic granulomatous prostatitis. The diagnosis is made after biopsy of the prostate.

B. MANAGEMENT

Some patients respond to antibiotic therapy, corticosteroids, and temporary bladder

drainage. Those with eosinophilic granulomatous prostatitis dramatically response to

corticosteroids (Ohkawa, Yamaguchi, and Kobayashi, 2001). Transurethral resection of the

prostate may be required in patients who do not respond to treatment and have significant

outlet obstruction.

Prostate Abscess

Most cases of prostatic abscess result from complications of acute bacterial prostatitis that

were inadequately or inappropriately treated. Prostatic abscesses are often seen in patients

with diabetes; those receiving chronic dialysis; or patients who are immunocompromised,

undergoing urethral instrumentation, or who have chronic indwelling catheters.

A. PRESENTATION AND FINDINGS

Patients with prostatic abscess present with similar symptoms to those with acute bacterial

prostatitis. Typically, these patients were treated for acute bacterial prostatitis previously

and had a good initial response to treatment with antibiotics. However, their symptoms

recurred during treatment, suggesting development of prostatic abscesses. On digital rectal

examination, the prostate is usually tender and swollen. Fluctuance is only seen in 16% of

patients with prostatic abscess (Weinberger et al, 1988).

B. RADIOLOGIC IMAGING

Imaging with transrectal ultrasonography (Figure 13–7) or pelvic CT scan is crucial for

diagnosis and treatment.

C. MANAGEMENT

Antibiotic therapy in conjunction with drainage of the abscess is required. Transrectal

ultrasonography or CT scan can be used to direct transrectal drainage of the abscess

(Barozzi et al, 1998). Transurethral resection and drainage may be required if transrectal

drainage is inadequate. When properly diagnosed and treated, most cases of prostatic

abscess resolve without significant sequelae

(Weinberger et al, 1988).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 6.4.1 StudyDocumento8 pagine6.4.1 StudyAndrew MNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocumento23 pagineUrinary Tract InfectionAs SyarifNessuna valutazione finora

- A. P F A. P F: Resentation and IndingsDocumento1 paginaA. P F A. P F: Resentation and Indingsietram12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Bacterial ProstatitisDocumento5 pagineDiagnosis and Treatment of Bacterial ProstatitislobeseyNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Bacterial Prostatitis - UpToDateDocumento18 pagineAcute Bacterial Prostatitis - UpToDateFernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacterial Uropathogenic FactorsDocumento7 pagineBacterial Uropathogenic FactorsAtma AdiatmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Bacterial ProstatitisDocumento27 pagineAcute Bacterial ProstatitisJood AL AbriNessuna valutazione finora

- Prostatitis PDFDocumento3 pagineProstatitis PDFWidya PuspitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prostatitis Background: Overview#showallDocumento5 pagineProstatitis Background: Overview#showallAnonymous gMLTpER9IUNessuna valutazione finora

- An Individual Case Study ON Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) : Southern Isabela General HospitalDocumento20 pagineAn Individual Case Study ON Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) : Southern Isabela General HospitalhanapotakoNessuna valutazione finora

- Symptoms: For Bladder InfectionsDocumento5 pagineSymptoms: For Bladder InfectionsGene Ryuzaki SeseNessuna valutazione finora

- Approach To Urinary Tract InfectionsDocumento17 pagineApproach To Urinary Tract InfectionsManusama HasanNessuna valutazione finora

- ProstatitisDocumento23 pagineProstatitisDoha Ebed100% (1)

- Urinary Tract Infection - A Suitable Approach: Lecture NotesDocumento7 pagineUrinary Tract Infection - A Suitable Approach: Lecture NotesMary Hedweg OpenianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Background of CaseDocumento8 pagineBackground of CaseKathleen Castro MojicaNessuna valutazione finora

- BAHAN KULIAH - Urinary Tract InfectionDocumento24 pagineBAHAN KULIAH - Urinary Tract Infectionevi_kkITNessuna valutazione finora

- CYSTITIS!Documento12 pagineCYSTITIS!crave24Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gyno Review: Final Surgery Exam 2011Documento36 pagineGyno Review: Final Surgery Exam 2011Zee TeeNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 UtiDocumento65 pagine5 Utimunanira prosperNessuna valutazione finora

- Genitourinary TB: DR Alexandre Nyirimodoka, MD, Mmed, Fcs (Ecsa) Urologist RMHDocumento24 pagineGenitourinary TB: DR Alexandre Nyirimodoka, MD, Mmed, Fcs (Ecsa) Urologist RMHRwabugili ChrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Prostatic Abscess - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento14 pagineProstatic Abscess - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfSheshang KamathNessuna valutazione finora

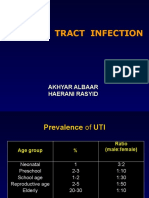

- Urinary Tract Infection: Akhyar Albaar Haerani RasyidDocumento49 pagineUrinary Tract Infection: Akhyar Albaar Haerani Rasyidrolly riksantoNessuna valutazione finora

- U Rinary Tract InfectionsDocumento43 pagineU Rinary Tract Infectionssudesh.manipal12Nessuna valutazione finora

- ####Bahan Kuliah ISK Blok 23 (Nov 2015)Documento32 pagine####Bahan Kuliah ISK Blok 23 (Nov 2015)ajengdmrNessuna valutazione finora

- The Challenge of Urinary Tract Infections in Renal Transplant RecipientsDocumento14 pagineThe Challenge of Urinary Tract Infections in Renal Transplant RecipientsdevinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infections د.أحمد الأهنوميDocumento44 pagineUrinary Tract Infections د.أحمد الأهنوميMohammad BelbahaithNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 Urological InfectionsDocumento18 pagine17 Urological InfectionsntadudulNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinarytract InfectionDocumento61 pagineUrinarytract InfectionsanjivdasNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis MedscapeDocumento9 pagineChronic Bacterial Prostatitis MedscapeAnonymous gMLTpER9IUNessuna valutazione finora

- I. Urinary Tract Infections Overview: A. Acute Uncomplicated UTI in WomenDocumento13 pagineI. Urinary Tract Infections Overview: A. Acute Uncomplicated UTI in WomenDominique VioletaNessuna valutazione finora

- Renal Notes Step 2ckDocumento34 pagineRenal Notes Step 2cksamreen100% (1)

- Evaluation and Management UTI in Emergency-1-10Documento10 pagineEvaluation and Management UTI in Emergency-1-10Ade PrawiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 36 The Urinary System in GynaecologyDocumento19 pagineChapter 36 The Urinary System in Gynaecologypmj050gpNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection: Syakib Bakri, Hasyim Kasim, Haerani RasyidDocumento24 pagineUrinary Tract Infection: Syakib Bakri, Hasyim Kasim, Haerani RasyidYusran Ady FitrahNessuna valutazione finora

- ProstatitisDocumento9 pagineProstatitisjhon934934Nessuna valutazione finora

- Genitourinary Infections For ClassDocumento74 pagineGenitourinary Infections For ClassKashif BurkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pyelonephritis: Departemen Ilmu Penyakit Dalam FK Uii YogyakartaDocumento33 paginePyelonephritis: Departemen Ilmu Penyakit Dalam FK Uii YogyakartaAndaru Tri Setyo WibowoNessuna valutazione finora

- qfrUTI EditDocumento9 pagineqfrUTI EditMylz MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- qfrUTI EditDocumento9 pagineqfrUTI EditMylz MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocumento50 pagineUrinary Tract InfectionAhmad SobihNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute CystitisDocumento46 pagineAcute CystitisZainudine MhdNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Bacterial Prostatitis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento6 pagineAcute Bacterial Prostatitis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfMilton FabianNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) in Males: Signs and SymptomsDocumento33 pagineUrinary Tract Infection (UTI) in Males: Signs and Symptomssyak turNessuna valutazione finora

- Itu 2015Documento16 pagineItu 2015pipeemezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection: Tbilisi Referral Hospital, Tbilisi, Georgia Nephrologist Nino MaglakelidzeDocumento50 pagineUrinary Tract Infection: Tbilisi Referral Hospital, Tbilisi, Georgia Nephrologist Nino MaglakelidzePayal bhagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Specific Infections of The Genitourinary SystemDocumento47 pagineNon-Specific Infections of The Genitourinary SystemAngela RosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infections, Pyelonephritis, and ProstatitisDocumento27 pagineUrinary Tract Infections, Pyelonephritis, and Prostatitisnathan asfahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Uti ReadingsDocumento6 pagineUti ReadingskarenbelnasNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocumento24 pagineUrinary Tract InfectionraddagNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection - Kuliah Mahasiswa - Ferbruari 2017 - EDITDocumento52 pagineUrinary Tract Infection - Kuliah Mahasiswa - Ferbruari 2017 - EDITRahmawati HamudiNessuna valutazione finora

- NCP Nursing Care Plan For Urinary Tract InfectionsDocumento4 pagineNCP Nursing Care Plan For Urinary Tract InfectionsRaveen mayi89% (9)

- Acog Practice BulletinDocumento10 pagineAcog Practice BulletinCristian AranibarNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract InfectionsDocumento6 pagineUrinary Tract Infectionspat_tienmin4552Nessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocumento50 pagineUrinary Tract Infectionpokhara gharipatanNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection: CC Ricky G. JalecoDocumento56 pagineUrinary Tract Infection: CC Ricky G. JalecoRicky JalecoNessuna valutazione finora

- Genitourinary Tract InfectionsDocumento80 pagineGenitourinary Tract Infectionsraene_bautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento7 pagineCaseTroy MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urinary Tract Infection in Children - Classification, Diagnosis and TreatmentDa EverandUrinary Tract Infection in Children - Classification, Diagnosis and TreatmentNessuna valutazione finora

- Female Urinary Tract Infections in Clinical PracticeDa EverandFemale Urinary Tract Infections in Clinical PracticeBob YangNessuna valutazione finora

- Infections in Cancer Chemotherapy: A Symposium Held at the Institute Jules Bordet, Brussels, BelgiumDa EverandInfections in Cancer Chemotherapy: A Symposium Held at the Institute Jules Bordet, Brussels, BelgiumNessuna valutazione finora

- Format BagusDocumento36 pagineFormat BagusSyahidatul Kautsar NajibNessuna valutazione finora

- Bell's PalsyDocumento13 pagineBell's Palsyfachrie saputraNessuna valutazione finora

- Translate Jurnal Renal TractDocumento43 pagineTranslate Jurnal Renal TractZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 3 25Documento4 pagine2 3 25Zammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Watercolor Free Powerpoint TemplateDocumento25 pagineWatercolor Free Powerpoint TemplateZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abstract Background Leaves Google Slides TemplateDocumento39 pagineAbstract Background Leaves Google Slides TemplateTarcizio MacedoNessuna valutazione finora

- Block 0: Beginning Block: Case Processing SummaryDocumento3 pagineBlock 0: Beginning Block: Case Processing SummaryZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Referensi Nilai Lab NormalDocumento4 pagineReferensi Nilai Lab NormalMuhammad Fikru RizalNessuna valutazione finora

- Arterial DiseaseDocumento1 paginaArterial DiseaseZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kuliah Ums Enzym JantungDocumento24 pagineKuliah Ums Enzym JantungZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardvascsurg - Interv For Medstud2016Documento66 pagineCardvascsurg - Interv For Medstud2016Zammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecg Rhythm RecognitionDocumento38 pagineEcg Rhythm RecognitionFahmi SuhandinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharyngitis 0104 SlidesDocumento144 paginePharyngitis 0104 SlidesZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardvascsurg - Interv For Medstud2016Documento66 pagineCardvascsurg - Interv For Medstud2016Zammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aerodigestive-Benda Asing Kuliah5Documento61 pagineAerodigestive-Benda Asing Kuliah5Adjeng Retno Bintari IINessuna valutazione finora

- Broncho - Oesophagology: KRH. Dr. H. Djoko S. Sindhusakti SP - THT - KL (K), Mba, Mars, MsiDocumento18 pagineBroncho - Oesophagology: KRH. Dr. H. Djoko S. Sindhusakti SP - THT - KL (K), Mba, Mars, MsiMuhammad Nur SidiqNessuna valutazione finora

- Ronald Deskin, 2002Documento60 pagineRonald Deskin, 2002Ratna Puspa RahayuNessuna valutazione finora

- Larynx Path 2002 01 SlidesDocumento140 pagineLarynx Path 2002 01 SlidesZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Larynx Path 2002 01 SlidesDocumento140 pagineLarynx Path 2002 01 SlidesZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aspirasi Korpal Kuliah6Documento43 pagineAspirasi Korpal Kuliah6Arif Nugroho SetiawanNessuna valutazione finora

- B4751Documento43 pagineB4751Zammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharyngitis 0104 SlidesDocumento144 paginePharyngitis 0104 SlidesZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulcer Mouth Kuliah Stomatologi1Documento62 pagineUlcer Mouth Kuliah Stomatologi1Zammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Special Test Musculoskeletal: Retno Setianing Rs Ortopedi Prof DR R Soeharso SurakartaDocumento24 pagineSpecial Test Musculoskeletal: Retno Setianing Rs Ortopedi Prof DR R Soeharso SurakartaZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Congen SYDocumento28 pagineCongen SYZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- DHF Menurut WHO 2011Documento212 pagineDHF Menurut WHO 2011Jamal SutrisnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kuliah Proses RadangDocumento38 pagineKuliah Proses RadangZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Congen SYDocumento28 pagineCongen SYZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Basal Cell CarcinomaDocumento3 pagineBasal Cell CarcinomaZammira MutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- TB - OutlineDocumento11 pagineTB - Outlinekent yeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation and Management of Young Febrile Infants 2023Documento12 pagineEvaluation and Management of Young Febrile Infants 2023Felipe MayorcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bot 101 NotesDocumento2 pagineBot 101 NotesAbid Hussain100% (1)

- Probiotic Drops PresentationDocumento21 pagineProbiotic Drops PresentationThảo PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- CPG Management of Genital Ulcers and DischargesDocumento103 pagineCPG Management of Genital Ulcers and DischargesardhianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Malaria: What Happens in MalariaDocumento3 pagineMalaria: What Happens in MalariakewpietheresaNessuna valutazione finora

- Id MMD 2Documento9 pagineId MMD 2Nashrah HusnaNessuna valutazione finora

- MycetomaDocumento26 pagineMycetomaTummalapalli Venkateswara RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- By:Ruma Daniel Hendry Kyambogo University Bsc. Human Nutrition and Dietetics. (Yr Two) TEL: 0755514951/0786224870 EmailDocumento12 pagineBy:Ruma Daniel Hendry Kyambogo University Bsc. Human Nutrition and Dietetics. (Yr Two) TEL: 0755514951/0786224870 EmailRUMA DANIEL HENDRYNessuna valutazione finora

- Diphtheria ReportDocumento13 pagineDiphtheria ReportAubrey SungaNessuna valutazione finora

- 070 - 1235 - Dewi Purnamasari - GalleyDocumento6 pagine070 - 1235 - Dewi Purnamasari - Galley2pr6ztzzbwNessuna valutazione finora

- Encyclopedia of Virology Fourth Edition V1 5 Dennis Bamford Full ChapterDocumento67 pagineEncyclopedia of Virology Fourth Edition V1 5 Dennis Bamford Full Chapterrobert.hanson139100% (5)

- WHO Guidelines For Hand Hygiene in Health CareDocumento216 pagineWHO Guidelines For Hand Hygiene in Health CarescretchyNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To MicrobiologyDocumento55 pagineIntroduction To MicrobiologyAngelica Valdez BalmesNessuna valutazione finora

- Microbial Contamination of Pharmaceutical PreparationsDocumento6 pagineMicrobial Contamination of Pharmaceutical PreparationsReiamury AzraqNessuna valutazione finora

- A Molecular Perspective of Microbial Pathogenicity PDFDocumento11 pagineA Molecular Perspective of Microbial Pathogenicity PDFjon diazNessuna valutazione finora

- Brochure For World Health Day 7 April 2011Documento2 pagineBrochure For World Health Day 7 April 2011Dody FirmandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Food AOAC-991.14 PDFDocumento2 pagineFood AOAC-991.14 PDFDaniela VenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Sparvix Publishing House ProjectDocumento100 pagineSparvix Publishing House ProjectDhiraj PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- CPH 2212 Unit 5 Written AssignmentDocumento3 pagineCPH 2212 Unit 5 Written Assignmentunclet12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ultra Structure of ProkaryoteDocumento3 pagineUltra Structure of ProkaryoteselvasrijaNessuna valutazione finora

- HIVDocumento56 pagineHIVenkinga75% (8)

- ผื่นแพ้ยาDocumento26 pagineผื่นแพ้ยาKururin Kookkai KurukuruNessuna valutazione finora

- ParagisDocumento15 pagineParagisNeil Francel D. MangilimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathogenesis of BacteriaDocumento17 paginePathogenesis of Bacteriayiy yuyNessuna valutazione finora

- Incision and Drainage (I & D) Treatment of Abscesses in An Emergency DepartmentDocumento2 pagineIncision and Drainage (I & D) Treatment of Abscesses in An Emergency DepartmentConvaTecWoundNessuna valutazione finora

- IMAEC Disinfectant Product Catalogue - DigitalCopy - April - 2023Documento32 pagineIMAEC Disinfectant Product Catalogue - DigitalCopy - April - 2023ToureNessuna valutazione finora

- Outbreaks Epidemics and Pandemics ReadingDocumento2 pagineOutbreaks Epidemics and Pandemics Readingapi-290100812Nessuna valutazione finora

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 pagineAnnotated BibliographyStanley PierreNessuna valutazione finora