Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Halitosis: An Overview of Epidemiology, Etiology and Clinical Management

Caricato da

Bechah Kak MaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Halitosis: An Overview of Epidemiology, Etiology and Clinical Management

Caricato da

Bechah Kak MaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Periodontics

Review Article

Periodontics

Halitosis: an overview of epidemiology,

etiology and clinical management

Cassiano Kuchenbecker Rösing(a) Abstract: Halitosis is an unpleasant condition that causes social re-

Walter Loesche(b) straint. Studies worldwide indicate a high prevalence of moderate halito-

sis, whereas severe cases are restricted to around 5% of the populations.

Department of Periodontology, Dental

(a) The etiological chain of halitosis relates to the presence of odoriferous

School, Universidade Federal do Rio substances in exhaled air, especially the volatile sulphur compounds

Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

(VSC) produced by bacteria. The organoleptic diagnosis is the gold stan-

Department of Microbiology and

(b)

dard and clinical management includes oral approaches, especially peri-

Immunology, School of Dentistry, University

odontal treatment and oral hygiene instructions, including the tongue.

of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

When oral strategies are not successful, referral to physicians is warrant-

ed.

Descriptors: Halitosis; Epidemiology; Microbiology; Review.

Introduction

Halitosis is defined as breath that is offensive to others, caused by a

variety of reasons including but not limited to periodontal disease, bacte-

rial coating of tongue, systemic disorders and different types of food.1 It

is one of the most frequent claims from patients to the dentist. 2

After the decline in the prevalence of oral diseases of major preva-

lence, Dentistry has given it a closer attention, which should not be con-

sidered a cosmetic problem. However, science behind the understand-

ing of halitosis is weak. Several clinical approaches are based strictly on

opinions. The present review will focus on different aspects of halitosis,

trying to demonstrate the most appropriate evidence to support the ap-

proach for its management.

Epidemiology

Declaration of Interests: The authors Descriptive studies

certify that they have no commercial or

associative interest that represents a conflict The prevalence of halitosis has been studied in groups of individu-

of interest in connection with the manuscript. als found in different parts of the world in convenience samples. Dif-

ferent assessments and cut-off points are presented. Therefore, precise

estimates of the prevalence of halitosis are not possible to obtain. Table

Corresponding author:

Cassiano Kuchenbecker Rösing 1 describes descriptive epidemiological studies that document the preva-

E-mail: ckrosing@hotmail.com lence of halitosis. They indicate that moderate chronic halitosis affects

approximately one third of the groups, whereas severe halitosis may in-

volve less than 5% of the population. It is clear that halitosis is a preva-

lent problem, and that the dental profession needs to take its responsibil-

Received for publication on Jul 10, 2011

Accepted for publication on Sep 01, 2011 ity in managing it.

466 Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71

Rösing CK, Loesche W

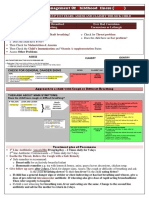

Table 1 - Summary of descriptive epidemiological studies concerning halitosis.

Author/year Location N Sampling procedure Halitosis measurement Main results

2672 government

Miyazaki et al., Convenience Prevalence of moderate halitosis

Japan workers, VSC (Halimeter)

19953 sample (≥ 75 ppb) = 28%

18-64 years

Prevalence of self

Loesche et al., 270 adults, Convenience perception = 31%

USA Self-report

19964 60+ years sample Prevalence of halitosis informed

by others = 24%

Frexinos et al., 4815 individuals, Randomized, Prevalence of self-reported

France Self-report

19985 15+ years representative halitosis = 22%

Söder et al., Stockholm, 1681 adults, Randomized, Prevalence of severe halitosis

Organoleptic

20006 Sweden 30-40 years, representative (score 5) = 2.4%

Nalçaci et al., Middle Anatolia, 628 children, 7-11 Convenience Prevalence of

Organoleptic

20087 Turkey years sample halitosis = 14.5%

Prevalence of organoleptic

score 3+ = 11.5%

Self-report,

Bornstein et al., Bern, 419 adults, Randomized, Prevalence of self-reported

Organoleptic

20098 Switzerland 18-94 years 21% response halitosis = 32%

and VSC

Prevalence of

VSC 75+ ppb = 28%

Prevalence of detected chronic

626 male

Bornstein et al., Convenience Self-report and halitosis = 20%

Switzerland army recruits,

20099 sample clinical analysis Prevalence of individuals without

18-25 years

halitosis experience = 17%

Prevalence of halitosis

experience (anxiety or

Yokoyama et al., 474 senior high Convenience Self report and consciousness of the problem at

Japan

201010 school students sample clinical analysis least once) = 42%

Prevalence of clinically

detectable malodor = 39.6%

Associated factors logical factors; however, in order not to undertake

A study in Sweden6 observed that calculus, the responsibility for treatment, it would sometimes

plaque and scarce dental visits were significantly emphasize non-oral causes of halitosis. Thus, the

correlated to severe halitosis. A Japanese study3 cor- stomach was, for years, blamed for the presence of

related periodontitis and tongue coating to VSC halitosis. Several studies have demonstrated that the

scores. Also, severe periodontitis patients presented mouth is the origin for the majority of halitosis. 2,11

higher halitosis scores than non-periodontal pa- Eighty-seven percent of the incoming patients with

tients. In the two Swiss studies8,9 tongue coating was severe malodor who attended a specialized clinic for

considered an influencing factor for halitosis. Smok- halitosis in Belgium11 had their problem related to

ing and periodontal disease were associated with oral factors. Gingivitis and periodontitis accounted

higher halitosis rankings.8 Plaque and tongue coat- for approximately 60% of the oral factors and the

ing were associated with halitosis.10 In children, car- tongue accounted for the other 40%. A subsequent

ies experience and age were associated to malodor.7 report by the same group12 found oral factors as

Whether these associations are causal is not clear. responsible for halitosis in 76% of 2000 patients.

Therefore, Dentistry is responsible for diagnosing

Etiology and treating halitosis.

The etiology of halitosis has been subject to a

historical controversy. 2 Dentistry claimed oral etio-

Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71 467

Halitosis: an overview of epidemiology, etiology and clinical management

Periodontal inflammation treatment improves halitosis measurements. Stressful

The presence of microorganisms and the inflam- situations also might contribute to increase halito-

matory products present in gingivitis/periodontitis sis.23 In some individuals, the complaint of halitosis

are capable of producing odoriferous substances. cannot be associated with either the ability of the

Cross-sectional studies associated halitosis to the clinician to detect odors or with the demonstration

presence of either gingivitis or periodontitis.3,8,9,11,12 of VSC in the exhaled air. This paradoxical situation

In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the ability has been classified as halitophobia, an important

of putative periodontal pathogens and products of psychological problem that needs to be addressed

inflammation to produce volatile odoriferous com- with non-oral clinical strategies.6,12

pounds.13,14,15,16 Therefore, the presence of periodon-

tal inflammation needs to be considered in the man- Clinical management

agement of halitosis. Diagnosis

Self-assessment

Tongue coating The patient cannot smell his own breath and re-

Tongue coating, including bacteria, desquamated lies upon others for this information. It should be

cells, and saliva, among others, is one of the impor- emphasized that it is a difficult task to tell someone

tant etiological factors of halitosis. A study12 demon- that he has bad breath. Thus, results from this kind

strated that tongue coating was associated with hali- of diagnosis should be interpreted with care. In a

tosis in more than 60% of 2000 patients of a breath breath clinic,11 more than 70% of the patients were

clinic, whether present alone, or with periodontal advised by others to seek treatment, whereas in an-

inflammation. Most studies implicate the coating on other study,4 only 24% of the elders were informed

the posterior area of the tongue which is consistent that they harbored bad breath. Of course, differences

with the presence of billions of bacteria, including from study populations might explain the dispar-

anaerobes that live there and are capable of produc- ity in results (the former being from a breath clinic

ing odoriferous substances.17 and the latter from a convenience sample of older

individuals). In the study by Bornstein et al.,8 a weak

Microbiology of halitosis correlation was observed between self-reported hali-

Bacteria from the saliva,18 from plaque removed tosis and clinical measurements.

from gingivitis/periodontitis16 as well as from the

tongue17 produce odoriferous substances in vitro. In- Organoleptic measurements

tervention studies which achieve a clinically signifi- The human nose remains the “Gold Standard” in

cant effect in reducing halitosis exhibit a reduction detecting oral halitosis. The most widely used scor-

in these bacteria.19,20 Therefore, the clinical manage- ing system for ranking halitosis is the Organoleptic

ment should also include microbiological targets, Score popularized by Rosenberg and McCulloch.24

with antimicrobial approaches – mechanical and The organoleptic measurement depends on a trained

chemical – being part of the strategy. examiner that has demonstrated reliability in smell-

ing halitosis. The study by Haas et al.25 has demon-

Non-oral causes of halitosis strated good levels of reproducibility of breath odor

Ear-nose-throat problems such as tonsillitis, si- measurements, under a blind evaluation. The reason

nusitis, the presence of out-of-body material and rhi- by which the organoleptic score has been the gold

nitis were frequently associated with non-oral halito- standard for breath measurements rely on the fact

sis in breath clinics.11,12 These studies were unable to that the human nose is capable of smelling and de-

find clinically relevant associations of halitosis with fining as pleasant/unpleasant not only the VSC, but

gastroenterological problems. However, two stud- also other organic compounds that come from exha-

ies21,22 demonstrated a possible association between lation and are identified as unpleasant.2

gastrointestinal problems and halitosis and that their

468 Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71

Rösing CK, Loesche W

VSC monitoring on compounds other than the VSC that contribute

Objective measurements have always been de- to halitosis. Kozlovsky et al.26 found that the BANA

sired for breath assessments. The most common mal- Test correlated significantly with the organoleptic

odorants detected in halitosis are VSC which include scores obtained from the whole mouth, the tongue

hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptans, among and saliva, but not with the VSC. When multiple-

others. VSC monitors have been developed, such as regression analyses were performed with the organ-

the Halimeter (Interscan, Chatsworth, USA) which is oleptic scores as the dependent variable, both peak

used chairside and provides both the patient and the VSC and the BANA scores factored into the regres-

professional an idea of the breath situation. A halim- sion, yielding significant associations. They conclude

eter score of ≥ 75 ppb is recognized as clearly detect- that the “BANA test may be a simple, adjunct assay

ed halitosis. It is important to understand that VSC together with volatile sulphide determination in or-

assessment, as well as other breath diagnostic tools der to provide additional quantitative data which

are subjected to great variation, especially between contribute to the overall association with odor-judge

different hours of the day, and are strongly affected estimation.”

by confounders.16 A connection between BANA-positive bacteria

and malodor was observed in English subjects27 us-

Microbiologic tests ing BAPNA as the trypsin-like substrate. Seventy

The VSC monitors detect from 18% to 67% of eight percent of the isolates from 23 subjects with

the odors represented by the organoleptic score. This organoleptic scores ≥ 3 were BAPNA positive, com-

is because the nose is detecting odors due to many pared with 35% to 40% BAPNA positive isolates

other compounds that are in the intra-oral air as a in the subjects with organoleptic scores of 2. Sub-

result of microbial metabolism. Most of these com- sequently, Stomatococcus mucilaginus, a gram-pos-

pounds cannot be easily measured, and some such itive, facultative, cocco-bacillus, was identified as

as volatile fatty acids (butyrate, propionate, etc.), a BAPNA-positive species that is indigenous to the

diamines (cadaverine, putrescine) and other foul- tongue. This indicates that a BANA-positive reaction

smelling products can only be measured by labora- in the tongue, while indicative of halitosis, is due to

tory based assays. the presence of a bacterial flora that may be unique

An alternative strategy would be to detect in to it.

plaque, or in the tongue coating, taken from individ-

uals with halitosis, those bacteria or their enzyme(s) Treatment

that can produce these compounds. Three species Periodontal therapy

associated with periodontal disease, Treponema Periodontal treatment decreases halitosis. How-

denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tanner- ever, studies concerning response to periodontal

ella forsythia, produce both VSC and volatile fatty therapy as the only therapeutic approach for halito-

acids. The detection of these bacteria might provide sis are scarce and sometimes the effects are limited,

additional information concerning factors contrib- especially because other sources of halitosis are not

uting to the individual’s malodor. These organisms considered. A study by Silveira et al.28 demonstrated

can be detected by the presence of an enzyme(s) that a strict supragingival plaque control is able to

that degrades benzoyl-DL-arginine-naphthylamide reduce VSC and organoleptic scores in periodonti-

(BANA), a synthetic trypsin substrate, forming a col- tis patients. The studies performed in breath clinics

ored compound. We have adapted this enzyme assay have also demonstrated the ability of periodontal

to a 5- to 10-minute chairside test – the BANA Test treatment measurements to reduce halitosis.11,12

(BANAMet LLC, Ann Arbor, USA) – that detects

the presence of this enzyme(s) in plaque and tongue Approaches directed to tongue coating

samples. Several studies have demonstrated that reducing

The BANA test provides additional information bacteria on the dorsum of the tongue will dimin-

Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71 469

Halitosis: an overview of epidemiology, etiology and clinical management

ish halitosis. A study concluded that tongue clean- chiatrist should be included.11,12,21,22,34

ing was one of the most important approaches for

halitosis.29 A systematic review30 demonstrated the Masking agents

potential of tongue cleaning, however the evidence When it is not possible to direct the treatment ap-

was not convincing. Also, a Cochrane systematic re- proach to the cause, masking agents have been devel-

view31 demonstrated that there is a little superiority oped to decrease the odor. The use of chewing gum

of tongue scrapers as compared to brushing in re- may decrease halitosis, especially through increasing

ducing halitosis. Therefore, tongue cleansing is one salivary secretion.35 Mouthrinses containing chlorine

of the components and should never be a sole treat- dioxide and zinc salts have a substantial effect in

ment for halitosis. masking halitosis, not allowing the volatilization of

the unpleasant odor.20,35 These approaches should be

Antimicrobials only used temporarily in order to improve satisfac-

Since the presence of microorganisms from oral tion of the patient.

biofilms is responsible for producing malodor, any

type of treatment approach that has impact in the Summary and Conclusions

oral microbiota has the potential of reducing halito- The present review demonstrated that halitosis is

sis. Mouthrinses, especially chlorhexidine and cetil- a common problem impacting individuals at all ages.

pyridinium chloride have been effective in reducing The main etiological factors include bacteria in the

halitosis.20,32 In addition, the use of dentifrices has oral cavity related especially to periodontal diseases

also been studied. Triclosan containing dentifrices, and the dorsum of the tongue. Medical aspects in-

for example, have demonstrated an interesting po- clude ear-nose-throat and gastroenterological prob-

tential in reducing VSC.33 lems. Since the majority of halitosis is related to the

mouth, the dental team should lead the treatment,

Medical approaches performing dental/periodontal treatment and per-

If oral approaches are not successful in reducing/ sonalized oral hygiene instructions. Antimicrobials

eliminating halitosis, patients should be referred to a have the potential of reducing halitosis and masking

physician. If the medical causes cannot be suspected, agents should be used temporarily. The literature, es-

the first professional to be referred is the otorhino- pecially with randomized clinical trials, is scarce and

laryngologist, followed by the gastroenterologist. If additional studies are needed.

halitophobia is considered, a psychologist or phsy-

References

1. American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of Periodontal French general population]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998

Terms. 4th ed. Chicago: American Academy of Periodontol- Oct;22(10):785-91. French.

ogy; 2001. 56 p. 6. Söder B, Johansson B, Söder PO. The relation between foetor

2. Loesche WJ, Kazor C. Microbiology and treatment of halito- ex ore, oral hygiene and periodontal disease. Swed Dent J.

sis. Periodontol 2000. 2002 Apr;28:256-79. 2000 Mar;24(3):73-82.

3. Miyazaki H, Sakao S, Katoh Y, Takehara T. Correlation be- 7. Nalçaci R, Dülgergil T, Oba AA, Gelgör IE. Prevalence

tween volatile sulphur compounds and certain oral health of breath malodour in 7-11-year-old children living in

measurements in the general population. J Periodontol. 1995 Middle Anatolia, Turkey. Community Dent Health. 2008

Aug;66(8):679-84. Sep;25(3):173-7.

4. Loesche WJ, Grossman N, Dominguez L, Schork MA. Oral 8. Bornstein MM, Kislig K, Hoti BB, Seemann R, Lussi A.

malodour in the elderly. In: van Steenberghe D, Rosenberg Prevalence of halitosis in the population of the city of Bern,

M, editors. Bad breath: a multidisciplinary approach. Leuven: Switzerland: a study comparing self-reported and clinical data.

Leuven University Press; 1996: 181-94. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009 Jun;117(3):261-7.

5. Frexinos J, Denis P, Allemand H, Allouche S, Los F, Bonnelye 9. Bornstein MM, Stocker BL, Seemann R, Bürgin WB, Lussi A.

G. [Descriptive study of digestive functional symptoms in the Prevalence of halitosis in young male adults: a study in swiss

470 Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71

Rösing CK, Loesche W

army recruits comparing self-reported and clinical data. J 22. Kinberg S, Stein M, Zion N, Shaoul R. The gastrointestinal

Periodontol. 2009 Jan;80(1):24-31. aspects of halitosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;24(9):552-

10. Yokoyama S, Ohnuki M, Shinada K, Ueno M, Wright FA, 6.

Kawaguchi Y. Oral malodor and related factors in Japanese 23. Queiroz CS, Hayacibara MF, Tabchoury CP, Marcondes FK,

senior high school students. J Sch Health. 2010 Jul;80(7):346- Cury JA. Relationship between stressful situations, salivary

52. flow rate and oral volatile sulfur-containing compounds. Eur

11. Delanghe G, Ghyselen J, Feenstra L, van Steenberghe D. Ex- J Oral Sci. 2002 Oct;110(5):337-40.

periences of a Belgian multidisciplinary breath odour clinic. 24. Rosenberg M, McCulloch CA. Measurement of oral malodor:

Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1997; Jan;51(1):43-8. current methods and future prospects. J Periodontol. 1992

12. Quirynen M, Dadamio J, Van den Velde S, De Smit M, De- Sep;63(9):776-82.

keyser C, Van Tornout M, et al. Characteristics of 2000 pa- 25. Haas AN, Silveira EM, Rösing CK. Effect of tongue cleansing

tients who visited a halitosis clinic. J Clin Periodontol. 2009 on morning oral malodour in periodontally healthy individu-

Nov;36(11):970-5. als. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5(2):89-94.

13. Yoneda M, Masuo Y, Suzuki N, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T. Re- 26. Kozlovsky A, Gordon D, Gelernter I, Loesche WJ, Rosenberg

lationship between the β-galactosidase activity in saliva and M. Correlation between the BANA test and oral malodor

parameters associated with oral malodor. J Breath Res. 2010 parameters. J Dent Res. 1994 May;73(5):1036-42.

Mar;4(1):17-8. 27. van Steenberghe D, Rosenberg M. Bad Breath: a Multidisci-

14. Kleinberg I, Codipilly M. Modeling of the oral malodor plinary Approach. 1st. Leuven: Leuven University Press; 1996.

system and methods of analysis. Quintessence Int. 1999 Assessment of impressed toothbrush as a method of sampling

May;30(5):357-69. tongue microbiota; p. 123-34.

15. Salako NO, Philip L. Comparison of the use of the Halimeter 28. Silveira EMV, Piccinin FB, Gomes SC, Oppermann RV, Rösing

and the Oral Chroma in the assessment of the ability of com- CK. The effect of gingivitis treatment on the breath of chronic

mon cultivable oral anaerobic bacteria to produce malodorous periodontitis patients. Oral Health Prev Dent. Forthcoming

volatile sulfur compounds from cysteine and methionine. Med 2011.

Princ Pract. 2011 Jan;20(1):75-9. 29. Faveri M, Hayacibara MF, Pupio GC, Cury JA, Tsuzuki CO,

16. De Boever EH, De Uzeda M, Loesche WJ. Relationship be- Hayacibara RM. A cross-over study on the effect of various

tween volatile sulfur compounds, BANA-hydrolyzing bacteria therapeutic approaches to morning breath odour. J Clin Peri-

and gingival health in patients with and without complaints odontol. 2006 Aug;33(8):555-60.

of oral malodor. J Clin Dent. 1994;4(4):114-9. 30. Van der Sleen MI, Slot DE, Van Trijffel E, Winkel EG, Van

17. Kazor CE, Mitchell PM, Lee AM, Stokes LN, Loesche WJ, der Weijden GA. Effectiveness of mechanical tongue cleaning

Dewhirst FE, et al. Diversity of bacterial populations on the on breath odour and tongue coating: a systematic review. Int

tongue dorsa of patients with halitosis and healthy patients.J J Dent Hyg. 2010 Nov;8(4):258-68.

Clin Microbiol. 2003 Feb;41(2):558-63. 31. Outhouse TL, Al-Alawi R, Fedorowicz Z, Keenan JV. Tongue

18. Takeshita T, Suzuki N, Nakano Y, Shimazaki Y, Yoneda M, scraping for treating halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

Hirofuji T, et al. Relationship between oral malodor and the 2006 19;(2):CD005519. [citado 27 jun 2011]. Disponível em:

global composition of indigenous bacterial populations in http://cochrane.bvsalud.org/cochrane/main.

saliva. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 May;76(9):2806-14. php?lib=COC&searchExp =Tongue%20and%20scrap-

19. Shinada K, Ueno M, Konishi C, Takehara S, Yokoyama S, ing%20and%20for%20and%20treating%20and%20

Zaitsu T,et al. Effects of a mouthwash with chlorine dioxide halitosis&lang=pt.

on oral malodor and salivary bacteria: a randomized placebo- 32. Carvalho MD, Tabchoury CM, Cury JA, Toledo S, Nogueira-

controlled 7-day trial. Trials. 2010 Feb 12;11:14. Filho GR. Impact of mouthrinses on morning bad breath in

20. Fedorowicz Z, Aljufairi H, Nasser M, Outhouse TL, Pedrazzi healthy subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 2004 Feb;31(2):85-90.

V. Mouthrinses for the treatment of halitosis. Cochrane Da- 33. Nogueira-Filho GR, Duarte PM, Toledo S, Tabchoury CP,

tabase Syst Rev. 2008;8(4):CD006701. [citado 27 jun 2011]. Cury JA. Effect of triclosan dentifrices on mouth volatile sul-

Disponível em: http://cochrane.bvsalud.org/cochrane/main. phur compounds and dental plaque trypsin-like activity during

php?lib=COC&searchExp =Mouthrinses%20and%20 experimental gingivitis development. J Clin Periodontol. 2002

for%20and%20the%20and%20treatment%20and%20 Dec;29(12):1059-64.

of%20and%20halitosis&lang=pt. 34. Iwu CO, Akpata O. Delusional halitosis. Review of the

21. Moshkowitz M, Horowitz N, Leshno M, Halpern Z. Halitosis literature and analysis of 32 cases. Br Dent J. 1990 Apr

and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a possible association. 7;168(7):294-6.

Oral Dis. 2007 Nov;13(6):581-5. 35. Rösing CK, Gomes SC, Bassani DG, Oppermann RV. Effect of

chewing gums on the production of volatile sulfur compounds

(VSC) in vivo. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2009 Jun;22(1):11-4.

Braz Oral Res. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):466-71 471

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Daygame by Todd Valentine NotesDocumento8 pagineDaygame by Todd Valentine NotesAdnanHassan100% (7)

- Pediatric Gynecology BaruDocumento79 paginePediatric Gynecology BaruJosephine Irena100% (2)

- 5 Easy Arabic Short Stories FoDocumento3 pagine5 Easy Arabic Short Stories FoBechah Kak Ma0% (1)

- Mudaaf (Possessed) and Mudaaf Ilaihi (Possessor)Documento6 pagineMudaaf (Possessed) and Mudaaf Ilaihi (Possessor)Bechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Japanese - Keigo II - KenjougoDocumento7 pagineBusiness Japanese - Keigo II - KenjougoBechah Kak Ma100% (1)

- Pitman SolutionDocumento190 paginePitman SolutionBon Siranart50% (2)

- Halitosis: An Overview of Epidemiology, Etiology and Clinical ManagementDocumento6 pagineHalitosis: An Overview of Epidemiology, Etiology and Clinical Managementdrmezzo68Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coban (2017) Halitosis: A Review of Current LiteratureDocumento7 pagineCoban (2017) Halitosis: A Review of Current LiteraturePhuong ThaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Title:: HalitosisDocumento12 pagineResearch Title:: Halitosisعمار محمد عباسNessuna valutazione finora

- 02-Zalewska Et AlDocumento10 pagine02-Zalewska Et AlNadya PuspitaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyDocumento5 pagine3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyarinilhaqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Dou (2016) Halitosis and Helicobacter Pylori InfectionDocumento7 pagineDou (2016) Halitosis and Helicobacter Pylori InfectionPhuong ThaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Harmouche (2021) Knowledge and Management of Halitosis in France and Lebanon: A Questionnaire-Based StudyDocumento13 pagineHarmouche (2021) Knowledge and Management of Halitosis in France and Lebanon: A Questionnaire-Based StudyPhuong ThaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis: Group: BDocumento7 pagineHalitosis: Group: Bزيد العراقيNessuna valutazione finora

- Australian Dental Journal - 2019 - Wu - Halitosis Prevalence Risk Factors Sources Measurement and Treatment A ReviewDocumento8 pagineAustralian Dental Journal - 2019 - Wu - Halitosis Prevalence Risk Factors Sources Measurement and Treatment A ReviewDita SyifaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review of The Current Literature On Aetiology and Measurement Methods of HalitosisDocumento9 pagineA Review of The Current Literature On Aetiology and Measurement Methods of HalitosisDito AnurogoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lechien Saussez Karkos Curr Opin 2018Documento12 pagineLechien Saussez Karkos Curr Opin 2018alivanabilafarinisaNessuna valutazione finora

- HalitosisDocumento6 pagineHalitosispratyusha vallamNessuna valutazione finora

- Diploma de Endodoncia Online 18-19Documento7 pagineDiploma de Endodoncia Online 18-19shivaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis (Pubmed)Documento5 pagineHalitosis (Pubmed)RikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitology Breath Odour Aetiopathogenesis and ManaDocumento14 pagineHalitology Breath Odour Aetiopathogenesis and Manadaniel_siitompulNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis The Multidisciplinary ApproachDocumento10 pagineHalitosis The Multidisciplinary Approachdaniel_siitompulNessuna valutazione finora

- An Update On Halitosis: Seven Common Questions: PeriodonticsDocumento4 pagineAn Update On Halitosis: Seven Common Questions: Periodonticsモハメッド アラーNessuna valutazione finora

- PODJ - Imraan and FarzeenDocumento6 paginePODJ - Imraan and Farzeendaniel_siitompulNessuna valutazione finora

- European Consensus Statement On Leptospirosis in Dogs and CatsDocumento21 pagineEuropean Consensus Statement On Leptospirosis in Dogs and Catsnashfitriyah hidayatNessuna valutazione finora

- Laryngopharyngeal Reflux and Voice DisordersDocumento20 pagineLaryngopharyngeal Reflux and Voice DisordersDiana RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Actual Concepts in Rhinosinusitis: A Review of Clinical Presentations, in Ammatory Pathways, Cytokine Profiles, Remodeling, and ManagementDocumento18 pagineActual Concepts in Rhinosinusitis: A Review of Clinical Presentations, in Ammatory Pathways, Cytokine Profiles, Remodeling, and ManagementAurum MortNessuna valutazione finora

- Cherian Et Al, 2012Documento5 pagineCherian Et Al, 2012julianasanjayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitology (Breath Odour: Aetiopathogenesis and Management) : Invited Medical ReviewDocumento13 pagineHalitology (Breath Odour: Aetiopathogenesis and Management) : Invited Medical Reviewdaniel_siitompulNessuna valutazione finora

- Investigation of Volatile Sulfur Compound Level and Halitosis in Patients With Gingivitis and PeriodontitisDocumento11 pagineInvestigation of Volatile Sulfur Compound Level and Halitosis in Patients With Gingivitis and PeriodontitisBilly TrầnNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral OdourDocumento4 pagineOral Odourerwin sutonoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorDocumento9 pagineA Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorNadya PuspitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Glositis Dan AtopiDocumento6 pagineGlositis Dan AtopiAmanda Rizka PutriNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Halitosis Current Concepts On Etiology Diagnosis and ManagementDocumento11 pagine2016 Halitosis Current Concepts On Etiology Diagnosis and ManagementDito AnurogoNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis: A Review of Associated Factors and Therapeutic ApproachDocumento11 pagineHalitosis: A Review of Associated Factors and Therapeutic ApproachdropdeadbeautifullNessuna valutazione finora

- Nasal Poly PosisDocumento4 pagineNasal Poly PosisDevita RamadaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Lichen Planus Clinical Features, Etiology, Treatment andDocumento7 pagineOral Lichen Planus Clinical Features, Etiology, Treatment andevhafadlianurNessuna valutazione finora

- 4092 24437 1 PBDocumento13 pagine4092 24437 1 PBCloudcynaraaNessuna valutazione finora

- Changes in Salivary Flow Rate and PH in Stressful ConditionsDocumento6 pagineChanges in Salivary Flow Rate and PH in Stressful ConditionsNgọc Kim Bảo NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- HalitosisDocumento11 pagineHalitosisWirajulay PratiwiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Halitosis Current Concepts On Etiology Diagnosis and ManagementDocumento17 pagine2016 Halitosis Current Concepts On Etiology Diagnosis and ManagementChristopher Tomás CataláNessuna valutazione finora

- Angular Cheilitis PDFDocumento4 pagineAngular Cheilitis PDFandi winayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Controversies in PeriodonticsDocumento56 pagineControversies in PeriodonticsReshmaa Rajendran100% (1)

- Lechien2018 Laryngopharyngeal Reflux TreatmentDocumento14 pagineLechien2018 Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Treatmentveronikakryshtal97Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Periodontal Therapy and The Adjunctive Effect of Antiseptics On Breath Odor-Related Outcome Variables: A Double-Blind Randomized StudyDocumento8 pagineThe Impact of Periodontal Therapy and The Adjunctive Effect of Antiseptics On Breath Odor-Related Outcome Variables: A Double-Blind Randomized StudyPhuong ThaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Update On Oral Lichen PlanusDocumento38 pagineUpdate On Oral Lichen PlanusBimalKrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Art:10.1007/s00784 010 0382 1Documento8 pagineArt:10.1007/s00784 010 0382 1Danis Diba Sabatillah YaminNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Dentistry and Oral SciencesDocumento19 pagineJournal of Dentistry and Oral SciencesNadya PuspitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiology of Dentin HypersensitivityDocumento6 pagineEpidemiology of Dentin HypersensitivityNaoki MezarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- TCRM 0402 507Documento7 pagineTCRM 0402 507Astie NomleniNessuna valutazione finora

- Ye 2020 J. Breath Res. 14 016005Documento12 pagineYe 2020 J. Breath Res. 14 016005Billy TrầnNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Lichen Planus or Oral Lichenoid Reaction? A Literature ReviewDocumento19 pagineOral Lichen Planus or Oral Lichenoid Reaction? A Literature ReviewAstrid Dwi SattiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cough Response To Aspiration in Thin and Thick Fluids During FEES in Hospitalized InpatientsDocumento10 pagineCough Response To Aspiration in Thin and Thick Fluids During FEES in Hospitalized InpatientsCC SusanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Proposed Usage of Intranasal Steroids and Antihistamines For Otitis Media With EffusionDocumento10 pagineThe Proposed Usage of Intranasal Steroids and Antihistamines For Otitis Media With Effusionfm_askaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cough Hypersensitivity Syndrome: A Few More Steps Forward: ReviewDocumento9 pagineCough Hypersensitivity Syndrome: A Few More Steps Forward: ReviewArif ONessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Review: LaryngitisDocumento6 pagineClinical Review: LaryngitisVirya WijayatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis Amongst Students in Tertiary Institutions in Lagos StateDocumento6 pagineHalitosis Amongst Students in Tertiary Institutions in Lagos StateChit Tat Thu LayNessuna valutazione finora

- Self-Reported Halitosis and Emotional StateDocumento6 pagineSelf-Reported Halitosis and Emotional StatePathivada LumbiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge and Attitude of Saudi Individuals Toward Self-Perceived HalitosisDocumento5 pagineKnowledge and Attitude of Saudi Individuals Toward Self-Perceived HalitosisChit Tat Thu LayNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review and Guide To Drug Associated Oral Adverse Effects-Oral Mucosal and Lichenoid Reactions. Part 2Documento10 pagineA Review and Guide To Drug Associated Oral Adverse Effects-Oral Mucosal and Lichenoid Reactions. Part 2Sheila ParreirasNessuna valutazione finora

- Halitosis From Diagnosis To Management PDFDocumento10 pagineHalitosis From Diagnosis To Management PDFOmer WahideNessuna valutazione finora

- Behçet's SyndromeDocumento7 pagineBehçet's Syndromeson gokuNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review of The Influence of Periodontal Treatment inDocumento12 pagineA Review of The Influence of Periodontal Treatment inTran DuongNessuna valutazione finora

- 46 Gruden PokupecDocumento3 pagine46 Gruden PokupecdrgozanNessuna valutazione finora

- C H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaDocumento15 pagineC H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughDa EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoNessuna valutazione finora

- ReefDocumento9 pagineReefBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- CoralReefFormations PDFDocumento28 pagineCoralReefFormations PDFBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Do Malaysians Trust Anwar IbrahimDocumento1 paginaDo Malaysians Trust Anwar IbrahimBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Deeper Shade of DiscriminationDocumento4 pagineA Deeper Shade of DiscriminationBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Al-Binaa & MabniDocumento1 paginaAl-Binaa & MabniBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- DocumentDocumento162 pagineDocumentBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Macrophotography: Creating An Elegant Ombre Background With f/2.8 LensDocumento10 pagineMacrophotography: Creating An Elegant Ombre Background With f/2.8 LensBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Verbal Sentence Starting With Verb of Third PersonDocumento1 paginaVerbal Sentence Starting With Verb of Third PersonBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- AlitqanDocumento644 pagineAlitqanBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- The i'Rab of Abun أَبٌ and Akhun أَخٌDocumento1 paginaThe i'Rab of Abun أَبٌ and Akhun أَخٌBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- New MH370 Probe Shows Controls Manipulated, But Mystery Remains UnsolvedDocumento3 pagineNew MH370 Probe Shows Controls Manipulated, But Mystery Remains UnsolvedBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- LandskapDocumento15 pagineLandskapBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shorghum ProductionDocumento14 pagineShorghum ProductionBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- CambodiaDocumento20 pagineCambodiaBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepositions & Jaar-MajroorDocumento4 paginePrepositions & Jaar-MajroorBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Zuriati BT Mohd Rashid - Muslims and Buddhists Interaction in Pasir Mas, KelantanDocumento28 pagineZuriati BT Mohd Rashid - Muslims and Buddhists Interaction in Pasir Mas, KelantanBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Does The Arabic Word Mashi MeanDocumento1 paginaWhat Does The Arabic Word Mashi MeanBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Istanbul Attarturk Airport MapDocumento1 paginaIstanbul Attarturk Airport MapBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Alitqan PDFDocumento644 pagineAlitqan PDFBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tridacna Giant ClamDocumento15 pagineTridacna Giant ClamBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- IRC To Examine JudiciaryDocumento3 pagineIRC To Examine JudiciaryBechah Kak MaNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical CodingDocumento5 pagineMedical CodingBernard Paul GuintoNessuna valutazione finora

- 11 - Morphology AlgorithmsDocumento60 pagine11 - Morphology AlgorithmsFahad MattooNessuna valutazione finora

- Section Thru A-A at S-1: Footing ScheduleDocumento1 paginaSection Thru A-A at S-1: Footing ScheduleJan GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 1 1489485680Documento52 pagineLecture 1 1489485680Dato TevzadzeNessuna valutazione finora

- Commercial Kitchen Fire InvestigationsDocumento6 pagineCommercial Kitchen Fire InvestigationsBen ConnonNessuna valutazione finora

- Wiring of The Distribution Board With RCD (Residual Current Devices) - Single Phase Home SupplyDocumento14 pagineWiring of The Distribution Board With RCD (Residual Current Devices) - Single Phase Home SupplyKadhir BoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 1Documento7 paginePresentation 1Abdillah StrhanNessuna valutazione finora

- South Valley University Faculty of Science Geology Department Dr. Mohamed Youssef AliDocumento29 pagineSouth Valley University Faculty of Science Geology Department Dr. Mohamed Youssef AliHari Dante Cry100% (1)

- Oasis AirlineDocumento5 pagineOasis AirlineRd Indra AdikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Famous Bombers of The Second World War - 1st SeriesDocumento142 pagineFamous Bombers of The Second World War - 1st Seriesgunfighter29100% (1)

- EMV Card Reader Upgrade Kit Instructions - 05162016Documento6 pagineEMV Card Reader Upgrade Kit Instructions - 05162016Shashi K KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Water Sensitive Urban Design GuidelineDocumento42 pagineWater Sensitive Urban Design GuidelineTri Wahyuningsih100% (1)

- Certificate of No Damages in EarthquakeDocumento5 pagineCertificate of No Damages in EarthquakeLemlem BardoquilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Bahasa Inggris PATDocumento10 pagineBahasa Inggris PATNilla SumbuasihNessuna valutazione finora

- Moldex Realty, Inc. (Linda Agustin) 2.0 (With Sound)Documento111 pagineMoldex Realty, Inc. (Linda Agustin) 2.0 (With Sound)Arwin AgustinNessuna valutazione finora

- WPCE Wireline Lubricator With Threaded Unions PDFDocumento1 paginaWPCE Wireline Lubricator With Threaded Unions PDFDidik safdaliNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hollow Boy Excerpt PDFDocumento52 pagineThe Hollow Boy Excerpt PDFCathy Mars100% (1)

- Diabetes in Pregnancy: Supervisor: DR Rathimalar By: DR Ashwini Arumugam & DR Laily MokhtarDocumento21 pagineDiabetes in Pregnancy: Supervisor: DR Rathimalar By: DR Ashwini Arumugam & DR Laily MokhtarHarleyquinn96 DrNessuna valutazione finora

- Dwnload Full Psychology Core Concepts 7th Edition Zimbardo Test Bank PDFDocumento13 pagineDwnload Full Psychology Core Concepts 7th Edition Zimbardo Test Bank PDFcomfortdehm1350100% (7)

- Faithgirlz Handbook, Updated and ExpandedDocumento15 pagineFaithgirlz Handbook, Updated and ExpandedFaithgirlz75% (4)

- Ae 2 PerformanceDocumento4 pagineAe 2 PerformanceankitNessuna valutazione finora

- IMCI UpdatedDocumento5 pagineIMCI UpdatedMalak RagehNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction: Science and Environment: Brgy - Pampang, Angeles City, PhilippinesDocumento65 pagineIntroduction: Science and Environment: Brgy - Pampang, Angeles City, PhilippinesLance AustriaNessuna valutazione finora

- English 3 Avicenna Graded Test 1Documento11 pagineEnglish 3 Avicenna Graded Test 1Mohd FarisNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Advent Herald (When God Stops Winking (Understanding God's Judgments) )Documento32 pagineSecond Advent Herald (When God Stops Winking (Understanding God's Judgments) )Adventist_TruthNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Jun 2010 Mark Scheme Unit 3Documento15 pagineChemistry Jun 2010 Mark Scheme Unit 3dylandonNessuna valutazione finora

- Operating Manual CSDPR-V2-200-NDocumento19 pagineOperating Manual CSDPR-V2-200-NJohnTPNessuna valutazione finora