Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

NRM Policies and Laws in Malawi

Caricato da

Mzee Boydd Mkaka MwabutwaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

NRM Policies and Laws in Malawi

Caricato da

Mzee Boydd Mkaka MwabutwaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

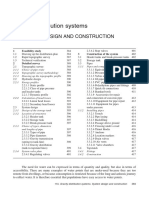

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

Table of Contents Page

1. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................1.1

1.1 Purpose and approach of the manual ...............................................................1.1

1.2 Principles and status of policy change ..............................................................1.1

1.3 Decentralization and natural resources management .....................................1.3

1.4 The formal process of policy and legal change.................................................1.4

1.5 The environment, rural life and local government in the Malawi Constitution

(1995), and other national-level statements on the environment....................1.4

2. ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ......................................................................2.1

2.1 The National Environmental Policy (1996) ......................................................2.1

2.2 The Environment Management Act (1996) ......................................................2.3

3. DECENTRALIZATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ...3.1

3.1 National Decentralization Policy (1998) and Local Government Act (1998) 3.1

3.2 Roles and responsibilities of district-level public officers and institutions....3.5

4. LAND USE AND MANAGEMENT........................................................................4.1

4.1 Preamble ..............................................................................................................4.1

4.2 The National Land Resources Management Policy and Strategy, 1998 (draft)

...............................................................................................................................4.2

4.3 The Use and Management of Private Land......................................................4.4

4.4 The Use and Management of Customary Land ...............................................4.7

4.5 Land use and management regulations made under the Environment

Management Act (1996) .....................................................................................4.8

4.6 The powers of District Assemblies over land ...................................................4.9

4.7 The role of public officers at district level ........................................................4.9

5. WATER AND IRRIGATION..................................................................................5.1

5.1 Introduction.........................................................................................................5.1

5.2 Water resources policy .......................................................................................5.2

5.3 The National Irrigation policy (2000) ...............................................................5.5

Environmental Affairs Department

v

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

5.4 Water sector legislation ......................................................................................5.6

5.5 Water sector functions and decentralization..................................................5.13

6. FORESTRY...............................................................................................................6.1

6.1 Preamble ..............................................................................................................6.1

6.2 The National Forest Policy, 1996.......................................................................6.1

6.3 The Forestry Act, 1997 .......................................................................................6.6

6.4 The roles of Forest Officers at district level ...................................................6.16

7. FISHERIES ...............................................................................................................7.1

7.1 Preamble ..............................................................................................................7.1

7.2 The National Fisheries and Aqua-culture Policy .............................................7.2

7.3 The Fisheries Conservation and Management Act (1997) ..............................7.4

7.4 The roles of Fisheries Officers at district level...............................................7.17

8. NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE .................................................................8.1

8.1 Preamble ..............................................................................................................8.1

8.2 The National Wildlife Policy (2000) ..................................................................8.2

8.3 The National Parks and Wildlife Act (1992), and proposed amendments ....8.6

8.4 Wildlife functions at district level....................................................................8.17

List of Tables

Table 5.1 Institutional Roles In The Water Sector, As Defined By The Draft Wrmp (1999)....... 5.4

Table 6:1 Legal Framework For Utilizing Indigenous Forest Products From Unallocated

Customary Land .......................................................................................................... 6.10

Table 6.2 Division Of Institutional Functions Within The Forestry Sector ................................ 6.16

Table 7.1 Division Of Institutional Functions Within The Fisheries Sector............................... 7.17

Environmental Affairs Department

vi

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 PURPOSE AND APPROACH OF THE MANUAL

This introduction examines the process of policy and legal reform that has occupied all of the NRM

sectors over recent years, and is still under way, and ends with a brief discussion of government

policy as expressed at the highest level – the Constitution. The remainder of the manual goes on to

deal with each of the major natural resources sectors in turn, beginning with the framework policy and

legislation on environmental management, which provides guidance and direction to the others. A

section is also included to cover those aspects of the Decentralisation Policy and the Local

Government Act, 1998, which relate directly to the environment and natural resources management.

Within each subject area the approach taken will be as follows:

• Firstly, all of the documents that make up the current legal framework will be listed, with

comments on their current status and any changes likely in the near future.

• Secondly, a brief interpretation of the main policy themes will be provided.

• A third section will deal in more detail with the current legal provisions for natural resource

management. In some cases (e.g. the chapter on decentralisation) it has proved clearer to

discuss the policy and the law at the same time. In defining duties, obligations and

possibilities for development a law is of course more important than a policy, but a good

understanding of policy issues is very helpful in the interpretation of the law.

• Finally, the specific responsibilities of professionals – both public servants and those working

in the non-governmental and private sectors – will be addressed.

As far as possible the manual has been compiled from policy and legal documents that are currently in

force, and as a convention throughout this manual quotations from policy documents are printed in

Univers Condensed italic font text Size 10 while quotations from laws and regulations are printed in

Tahoma Italic Font Size 9 Text. Quotations from draft legislation are printed in Comic Sans

MS Italic Font Size 9 and from other sources in Times New Roman Font italics. Every effort has

been made to ensure the accuracy of the material used, and each section of the manual has undergone

scrutiny both by a lawyer and by the responsible government department. However, some of the

issues are complex, and in some instances there remain unresolved issues and unanswered questions.

Feedback from the field will be invaluable when it comes to preparing revisions of the manual as the

legal and institutional framework changes. Please read this manual critically, and send your questions

or comments, either directly or via your District Environmental Officer, to:

Director of Environmental Affairs, Private Bag 394, Capital City, Lilongwe 3.

Telephone: 771 111; Fax: 773 379; E-mail: rpkabwaza@malawi.net

1.2 PRINCIPLES AND STATUS OF POLICY CHANGE

1.2.1 Resource tenure

A theme common to the new or developing policies for management of the biologically renewable

resources (forests, wildlife and fish) is the progressive transfer of resource tenure from the state to the

primary resource users, i.e. private landowners, communities, groups of communities or user

associations. The underlying premise is that state control of natural resources encourages open access

to the resource, whereas localised tenure systems imply restriction of access and therefore afford a

realistic opportunity for responsible management. The devolution of tenure does not mean an

abandonment of State responsibility. The handover of utilisation rights will be matched by a handover

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 1

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

of management responsibilities through a formalised and legally binding system of management

agreements between the State and the resource users. In practical terms the partition of rights and

responsibilities between State and user will lie somewhere on a continuum bounded at one extreme by

total State control (as, for example, in the core zones of protected areas) and at the other extreme by

total community control (as in a community woodlot). Between the extremes lie various options for

co-management, in which both rights and responsibilities are shared by the State and the users. In all

cases government will retain the overall responsibility for monitoring the effectiveness of resource

management, and may withdraw tenure rights in cases where responsibilities are not being met.

The transfer process will be slow. Working with communities to sensitise them to the opportunities

for NRM, develop or strengthen village-level institutions, design management plans and provide

training and advice is painstaking, expensive work. Once a certain momentum has been achieved

much of the sensitisation and some extension could probably be done by the communities themselves,

but the size of the task should not be underestimated. In the meantime, those resources not managed

by or in partnership with communities will remain the responsibility of government sectoral agencies.

1.2.2 Spreading the load: the partnership approach

Given government’s limitations in manpower and financial resources, it is essential that the best

possible use be made of the services and resources that can be provided by interested non-government

agencies. Partnerships with the private sector can be particularly effective wherever circumstances

favour the common interests of NRM and commercial enterprise. Current examples include:

• in the wildlife sector, tourist concession-holders in National Parks and Wildlife Reserves already

make a substantial contribution towards protected area management through the provision of

transport and other services to government personnel. Potential exists to strengthen such

partnerships provided the terms for investment are sufficiently attractive. Both within and outside

of protected areas, eco-tourism could play a much stronger role in wildlife conservation than it

does at present.

• the larger buyers of cash crops are beginning to develop extension networks which could be

harnessed towards improvements in land management. Innovative private sector extension

initiatives in agricultural production (including agro-forestry technologies) and marketing have

flourished in neighbouring Zambia with relatively low levels of donor support, although no

attempt has yet been made to replicate this type of enterprise in Malawi.

• the estate agriculture sector has already been engaged in the multiplication of planting material for

agro-forestry initiatives, and with increasing pressure on the estates from smallholder competition

the diversification into novel products will become more attractive. Of particular importance here

could be the production of certified seed for trees and inter-crops, and, ultimately, plantation

forestry.

Partnerships between government and NGOs are now numerous in Malawi, and although the capacity

of national NGOs remains weak there is a clear opportunity to use donor finance to assist their

growth. The strength of the NGO contribution lies in specialist skills and interests which can be

harnessed to complement the broader interventions of government, as exemplified by the many

NGO/donor/GoM partnerships in agro-forestry, the work of TRAFFIC in the study of wildlife trade or

the outreach role of the Wildlife and Environmental Society of Malawi in the forestry and wildlife

sectors.

1.2.3 New roles for Government

It is clear from the direction in which policies for NRM are moving that the reform process is defining

new roles for Government. Probably the most obvious are those associated with the shift from control

to collaboration in the agencies responsible for the renewable biological resources. Here, the

devolution of NRM will impose additional responsibilities on government until such time as the new

management regimes become effective, after which both contraction and reorientation are indicated.

Thus:

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 2

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

• Traditional resource management functions will remain important in the near term, but will be

progressively reduced as co-management and community management initiatives come into

effect. However, even in the longer term sufficient enforcement capacity must be retained to

support communities in their own regulatory functions and, where necessary, to protect them from

outside interests.

• An adaptable and responsive research capacity will be required in order to formulate

recommendations for co-management and community management and solve site-specific

problems in the field. Resource monitoring will remain a high priority.

• Increased extension capacity will be required over the medium term to help create and support

devolved management structures.

• In the longer term the nature of the extension effort will be required to change towards the

provision of specialist technical support. This could be achieved through the deployment of

smaller, more mobile and more highly trained extension units that would eventually replace the

large and unwieldy field services which, currently, government can neither support nor adequately

supervise.

The trend is towards the gradual reduction of government’s NRM functions to those of guidance and

appropriate regulation. In practical terms this implies paying much closer attention to policy issues, to

refining and intensifying both research and monitoring, and to providing a sound regulatory

framework and an enabling environment for the devolution of management functions, backed up by

smaller but more professional technical support and law enforcement services. Government agencies

will be encouraged both to downsize and to become more professional, while the implementation of

policy will rely increasingly on the resource users, the private sector and other development partners.

1.3 DECENTRALIZATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT

In October 1998 the Cabinet approved a National Decentralization Policy (NDP), which will

transform not only the functions of district administration, but also many of the functions that are

presently the responsibility of central government institutions. The policy devolves administrative and

political authority to the district level, and integrates governmental agencies at the district and local

levels into a single administrative unit. The new administrative and political institution is termed the

District Assembly1, and will comprise of elected members with full executive powers as well as non-

voting traditional and political leaders. The heads of government departments at district level will

form a secretariat or management team answerable to the Assembly through a Chief Executive. They

will no longer report directly to their parent Ministries.

The Ministries/Departments to be decentralized in this way include: Health; Education; Lands,

Housing, Physical Planning and Surveys; Fisheries; Forestry; Agriculture (including Animal Health

and Industry and Irrigation); Works and Supplies; Water; Community Development; Commerce and

Industry; Tourism; Environmental Affairs (EDOs only). These Ministries will retain responsibility for

policy formulation, law enforcement and inspectorate, the establishment of standards, training,

curriculum development and international representation. They will have direct links with local

authorities, as instruments of service delivery, over professional and operational issues, but they will

no longer exercise immediate control over activities at district level.

The decentralization process defines a new institutional framework for line agencies at the district

level, but does not in itself alter the roles of public officers. Chapter 3 of the manual examines the

implications for natural resources managers in more detail.

1

Local authority areas comprise Cities, Municipalities and Townships as well as Districts: each will have its

own Assembly.

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 3

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

1.4 THE FORMAL PROCESS OF POLICY AND LEGAL CHANGE

Under the terms of the Constitution (see section 1.5 below), the State is charged with the

responsibility of managing the nation’s natural resource endowment in trust for the people of Malawi.

However much the ownership of natural resources, or rights to use them, may be devolved to local

authorities, user groups or local communities, the government cannot relinquish that responsibility

and will always retain a central guiding role in natural resources management. When we are

discussing policy, we are referring here to government policy, although it is recognised that other

stakeholders – NGOs, donors – may have their own policies and priorities that may not always

coincide with those of the government. There is nothing in Malawi law that stipulates how

government policies are arrived at. In the past, policy was determined by senior civil servants, with

little or no external consultation (and quite often with equally little internal consultation). Today the

importance of consultation is widely accepted, and new policies are usually designed through a

process of extensive discussion with representatives of all primary stakeholders and other interested

government agencies. This process ends with the preparation of a draft policy document that is

presented by the Ministry concerned to the appropriate Cabinet Committee. After discussion in the

Cabinet Committee, and possibly further modification, the draft is presented to the full Cabinet. Upon

Cabinet’s approval, the draft becomes the policy of the government.

New statutes are typically prepared through a parallel process of consultation, under the guidance of

legal experts provided either by the Ministry of Justice or contracted privately. Once developed to the

satisfaction of the appropriate technical Ministry, a draft Bill is submitted to the parliamentary

draftsmen of the Ministry of Justice to ensure compliance with Malawi’s legal customs and norms.

The Legal Affairs Committee of the Cabinet is subsequently asked to consider the draft, a process

which may re-open discussion on technical issues. Once the Legal Affairs Committee is satisfied with

the draft it will be scheduled for presentation to the National Assembly, or Parliament. After a

successful second reading in Parliament, and with the inclusion of any amendments Parliament may

require, the Bill becomes an Act of Parliament and will be passed on to the President for his assent.

Even then, the new Act does not become effective until such time as a notice is published in the

Gazette informing the public of its entry into force.

Subsidiary legislation, or implementing regulations, do not require Parliamentary approval but need

only the approval of the responsible Minister. Again, they have no legal power before they are

published in the Gazette. As a rule, principal statutes or Acts of Parliament are used to give legal force

to the principles of policy, but the details of policy implementation, which may require more frequent

revision, are left to the subsidiary legislation. An exception to this rule is the issue of penalties –

although in a context of high inflation fines might be thought to be more appropriately dealt with in

the implementing regulations, the legal norm is that they may not be altered without the consent of

Parliament, and so they are always specified in the principal statutes.

1.5 THE ENVIRONMENT, RURAL LIFE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE

MALAWI CONSTITUTION (1995), AND OTHER NATIONAL-LEVEL

STATEMENTS ON THE ENVIRONMENT

The Malawi Constitution of 1995 lays a strong foundation for policy and legal reform in

environmental governance, and it also establishes the improvement of rural living standards as a

national policy objective. In Chapter III – Fundamental Principles - section 13 declares:

“The State shall actively promote the welfare and development of the people of Malawi by progressively

adopting and implementing policies and legislation aimed at achieving the following goals -

(a) To manage the environment responsibly in order to -

(i) prevent the degradation of the environment;

(ii) provide a healthy living and working environment for the people of Malawi;

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 4

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

(iii) accord full recognition to the rights of future generations by means of environmental

protection and the sustainable development of natural resources; and conserve and

enhance the biological diversity of Malawi; and

(iv) conserve and enhance the biological diversity of Malawi.

(b) To enhance the quality of life in rural communities and to recognize rural standards of living

as a key indicator of the success of Government policies.”

The real challenge to all who are involved in NRM in Malawi will be to achieve both of these

objectives simultaneously – to improve the living standards of rural communities without destroying

the environment in the process. Economic development will be a key function of the future local

government structures, and to that extent they will also play a vital role in environmental

management. The principles and objectives of local government are established in Chapter XIV,

section 146, as follows:

(1) There shall be local government authorities which shall have such powers as are vested in them by

this Constitution and an Act of Parliament.

(2) Local government authorities shall be responsible for the representation of the people over whom

they have jurisdiction, for their welfare and shall have responsibility for -

(a) the promotion of infrastructural and economic development, through the formulation and

execution of local development plans and the encouragement of business enterprise;

(b) the presentation to central government authorities of local development plans and the

promotion of the awareness of local issues to national government;

(c) the consolidation and promotion of local democratic institutions and democratic participation;

…

(3) Parliament shall, where possible, provide that issues of local policy and administration be decided

on at local levels under the supervision of local government authorities. …”

There are many other documents that deal with environmental issues at the national level. The most

important of these are the framework National Environmental Policy and the Environment

Management Act, 1996, which are described in Chapter 2, and the various sectoral policies and laws

which follow. But three other publications provide a great deal of background material and should be

considered essential reading for field practitioners:

1.5.1 The National Environmental Action Plan (1994)

The first NEAP, completed in 1994 after two years of work and now due for revision, marked a

milestone in the short history of environmental management in Malawi. The plan was compiled by 18

Task Forces, the membership of which was drawn from government agencies, parastatals, including

the University of Malawi, NGOs and the private sector – altogether 185 people representing 51

institutions. In addition, eight district consultative workshops (with three districts represented at each)

were held to ensure the participation of the wider public. A NEAP Secretariat was employed full-time

to guide the process and help in the production of a draft summary document. Once a summary draft

was available a national workshop was convened and a new process of consultation and review

initiated, until a third and final draft was accepted by the (then) National Committee for the

Environment. It is estimated that in total over 1,300 people contributed to the 1994 NEAP.

Some of the criticisms which have been levelled at the NEAP document may be attributed to this

broad consultative process – it was not produced behind closed doors by experts, and is not therefore

a particularly polished product. But this is also its great strength. None can doubt its universal support

and ownership, and out of the NEAP grew an equally strong National Environmental Policy. The

NEAP marked the birth of participatory policy-making in Malawi, and although no subsequent

initiative has ever quite matched it (none could ever quite afford to) it has permanently altered

changed the way in which such matters are tackled.

The NEAP identified nine key environmental issues: soil degradation; threats to forest, fisheries and

water resources; threats to biodiversity, including wildlife issues; human habitat degradation;

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 5

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

unsustainable population growth, climate change and air quality issues. The Action Plan contains an

analysis of the factors contributing to each of these problems, and of the interactions between them,

and proposes appropriate responses at the policy, strategic and operational levels.

1.5.2 The Environment Support Programme, 1998

The Environmental Support Programme (ESP) grew out of the NEAP and followed a similar process

of consultation. The intention of the ESP was to provide a coherent and inclusive investment

framework within which the Action Plan would be implemented.

“… The ESP has as its overall objective to integrate environmental concerns into the socio-economic

development of Malawi. It is intended to provide an umbrella framework incorporating strategies,

policies and priority programmes to address environmental problems. The ESP incorporates the

actions of many different actors (Government, NGOs, the private sector, donors and communities), all

of which play a crucial role in environmental management in Malawi. The ESP is also designed to

solicit resources to tackle Malawi’s key environmental issues, while providing a framework to help

reduce duplication of effort. …”

Malawi Government (1998) Malawi Environmental Support Programme. Volume I: Context and Programme

description. Environmental Affairs Department, Lilongwe. p. 1.

The format of the document is based on the nine priority environmental issues identified in the NEAP,

with the exception that wildlife has been added as a stand-alone issue in addition to its contribution to

biodiversity. Under each chapter heading a discussion of policy issues is followed by an outline of

priorities for investment, and a description of which parts of the investment programme are currently

funded. The ESP design was initiated in 1995, and the document was published in 1998.

A second part of the ESP is a database of all initiatives in environmental and natural resources

management under way or in the design stage in 1998. The database is classified on the bases of (a)

environmental issues addressed; (b) geographical location (districts); (c) implementing agency, and

(d) funding agency, and contains a great deal of information on the level of investment, technologies

and approaches used, and, where available, success achieved and problems encountered. The database

is a custom application which runs in Microsoft Access, and is available on a single 3.5”DD diskette

from the Environmental Affairs Department.

1.5.3 The State of the Environment Report (1998)

The 1998 State of the Environment Report (SOER) was the first published in accordance with the

EMA (1996) and indeed a first ever for Malawi. As its name implies, the document is a technical

status report and it was not therefore compiled through a broad participatory, but rather through the

expert contributions of national authorities on the environment and natural resources sectors. Its ten

chapters were drafted by senior civil servants (including two departmental Directors) and members of

the University of Malawi, with quality control applied through a multi-sectoral editorial committee.

The Technical Committee on the Environment and the National Council for the Environment

reviewed the technical content of the document.

The two principal purposes of the SOER were (a) to report on the current status of a number of

selected E/NRM indicators, and where possible to present historic time-series data to illustrate trends,

and (b) to report on progress made in implementing the NEAP. The SOER follows the NEAP format

in reporting on eight of the nine key environmental issues (population was omitted). The report

commences with two chapters of a cross-cutting nature: Environment Management in Malawi, which

reviews the current policy, legal and institutional framework for E/NRM, and adds a chapter entitled

“Environment and development” in which interactions between the environment and economic

development trends are analysed.

The first SOER shows up the difference in information status between sectors, in itself a valuable

exercise, and it remains an important benchmark and reference work for future study.

Environmental Affairs Department 1: 6

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

2. ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT

Framework Documents Key dates

Principal statute: The Environment Management Act, 1996 August, 1996

Subsidiary legislation:

Policy document: The National Environmental Policy February, 1996

Other publications: The National Environmental Action Plan 1994

Guidelines for Environmental Impact Assessment December, 1997

A Guide to the Environment Management Act, 1997 1997

The Environment Support Programme June, 1998

2.1 THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY (1996)

The National Environmental Policy (NEP), developed from the 1994 National Environmental Action

Plan (NEAP) and approved by Cabinet in 1996, was the first clear statement by the Government of

Malawi of the central principles of environmental and natural resource management policy,

developing in more detail the provisions of the new Constitution. The policy elaborates the rights and

responsibilities of individuals and communities in the management of the environment; states

Government’s responsibilities in environmental planning, impact assessment, audit and monitoring,

and outlines primary policy objectives and strategies in a number of key sectors. The development of

the NEP as an umbrella or framework policy was well timed to precede policy reforms in most of the

environment sectors, enabling sectoral reforms to proceed in a harmonised and co-ordinated fashion

rather than as piecemeal developments.

The policy document covers a very broad range of issues and sectors, and is logically organized into

goals/objectives, guiding principles and strategies. The goals and objectives are reproduced here in

order to show the scope and alignment of the NEP: its most important strategies are however

embodied in the Environment Management Act, and this document is explored in more detail in the

following pages.

2.1.1 Goals and Objectives of the National Environmental Policy

(this section follows the NEP chapter headings and reproduces all statements of objectives)

1.0 Preamble

2.0 Policy Goals and Guiding Principles

2.1 Overall Policy Goal

The overall policy goal is the promotion of sustainable social and economic development through the sound

management of the environment in the country.

2.2 Specific Policy Goals

2.2.1 Secure for all persons resident in Malawi now and in the future an environment suitable for their

health and well-being.

2.2.2 Promote efficient utilization and management of the country’s natural resources and encourage,

where appropriate, long-term self-sufficiency in food, fuelwood and other energy requirements.

2.2.3 Facilitate the restoration, maintenance and enhancement of the ecosystems and ecological processes

essential for the functioning of the biosphere and prudent use of natural resources.

2.2.4 Enhance public awareness of the importance of sound environmental understanding of various

environmental issues and participation in addressing them.

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 1

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

2.2.5 Promote co-operation with other Governments and relevant international/regional organizations, local

communities, Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and the private sector in the management and

protection of the environment.

3.0 Macro-Economic Policy Issues and Instruments

3.1 Alleviation of poverty

To improve human welfare and effective environmental management through poverty alleviation.

3.2 Economic Incentives for Improved Environmental Management

To ensure that individuals and economic entities are given appropriate incentives for sustainable resource use

and environmental protection.

4.0 Cross-Sectoral Policy Objectives, Principles and Instruments

4.1 Institutions

To create the institutional mechanisms needed to implement a National Environmental Policy.

4.2 Legislation

To create a legal framework for the implementation of the National Environmental Policy and sustainable

environmental management.

4.3 Environmental Planning

To ensure that national, regional and district development plans integrate environmental concerns, in order to

improve environmental management and ensure sensitivity to local concerns and needs.

4.4 Environmental Impact Assessment, Audits and Monitoring

To develop a system and guidelines for environmental impact assessment (EIA), audits, monitoring, and

evaluation so that adverse environmental impacts can be eliminated or mitigated and environmental benefits

enhanced.

4.5 Environmental Education and Public Awareness

To increase public and political awareness and understanding of the need for sustained environmental

protection, conservation and management.

4.6 Private Sector and Community Participation

(a) To mobilize initiatives and resources in the private sector, NGOs and CBOs to achieve sustainable

environmental management, and

(b) To involve local communities in environmental planning and actions at all levels and empower them to

protect, conserve and sustainably utilize the nation’s natural resources.

4.7 Environmental Human Resource Development and Research

(a) To provide training needed to implement a national programme of environmental protection, conservation

and management, and

(b) To carry out the basic and applied demand-driven research needed to support sustainable management of

the environment.

4.8 Gender, Youth and Children

To integrate gender, youth and children concerns in environmental planning decisions at all levels to ensure

sustainable social and economic development.

4.9 Demographic Planning

To ensure that the growth of the country’s population does not lead to environmental degradation.

4.10 Human Settlements and Health

To promote urban and rural housing planning services that provide all inhabitants with a healthy environment.

4.11 Air Quality and Climate Change

To minimize the adverse impact of climate change and to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

4.12 Conservation of Biological Diversity

To conserve, manage and utilize sustainably the country’s biological diversity (ecosystems, genetic resources

and species) for the preservation of the National Heritage.

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 2

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

4.13 Land Tenure and Land Use

To promote sustainable use of the land resources of Malawi, primarily, but not exclusively, for agricultural

purposes by strengthening and clearly defining security of tenure over land resources.

5.0 Sectoral Policy Objectives, Principles and Instruments

5.1 Agriculture and Livestock

To promote environmentally sound agricultural development by ensuring sustainable crop and livestock

production through ecologically appropriate production and management techniques, and appropriate legal and

institutional framework for sustainable environmental management.

5.2 Forestry

To manage forestry resources endowment in a sustainable manner to maximise benefits to the nation.

5.3 Fisheries

To manage fish resources for sustainable utilization, reduction [production?] and conservation of aquatic

biodiversity.

5.4 National Parks and Wildlife

To conserve and manage [wildlife in] National Parks, Wildlife Reserves and outside protected areas in such a

way as to ensure their protection, sustainable utilization, and reduction of people/wildlife conflicts.

5.5 Water Resources

To manage and use water resources efficiently and effectively so as to promote its conservation and

availability in sufficient quantity and acceptable quality.

5.6 Energy

To meet national energy needs with increased efficiency and environmental sustainability.

5.7 Industry and Mining

To ensure that industrial and mining activities conform to sustained natural resource utilization and protection

of the environment.

5.8 Tourism

To conserve and manage sustainably the nation’s unique tourist attractions.

5.9 Other Sectors

To ensure that all sectors of the economy optimise use of environmentally friendly technologies and undertake

mitigation measures for adverse environmental impacts.

2.2 THE ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ACT (1996)

“An Act to make provision for the protection and management of the environment and the conservation

and sustainable utilization of natural resources and for matters connected therewith and incidental

thereto”

The Environment Management Act (1996) (the EMA) is the instrument through which the NEP is

implemented. It gives strength to the principles outlined in the NEP, to the extent that wherever

sectoral legislation conflicts with the EMA the latter shall take precedence. It provides for the creation

of regulations on all aspects of environmental management, so that gaps or inconsistencies in sectoral

legislation may be easily rectified. It creates, for the first time, a firm legal framework for

environmental impact assessment and environmental audit. Most importantly, it establishes a National

Council for the Environment with considerable powers to mediate in situations of conflict, and it

accords to the Environmental Affairs Department responsibility for the co-ordination of

environmental monitoring, interventions and investments in the environment/natural resources sectors

as well as environmental education and awareness-raising. Just as the NEP provides a structural

framework for policy development across many sectors, so the EMA provides a legal framework for

the development of new sectoral legislation. The Act is structured as follows:

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 3

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

Part I – Preliminary

This part defines the short title (the Environment Management Act) (section 1) and provides a legal

interpretation of the many technical terms used (section 2). The definitions of such fundamental

concepts as “biological diversity”, “conservation”, “environment”, “pollution” and “waste” are clear

and useful.

Part II – General Principles

Part II contains powerful clauses which define the rights and responsibilities of individuals, the

ownership of natural resources and the relationship between the EMA and other relevant legislation. It

commences with a statement of the duty of all individuals to protect the environment:

“3.-(1) It shall be the duty of every person to take all necessary and appropriate measures to protect and

manage the environment and to conserve natural resources and to promote sustainable utilization of

natural resources …”

The following section builds on section 13 (d) of the Constitution, defining popular ownership of

Malawi’s natural resources:

“4. The natural and genetic resources of Malawi shall constitute an integral part of the natural wealth of the

people of Malawi and –

(a) shall be protected, conserved and managed for the benefit of the people of Malawi; and

(b) save for domestic purposes, shall not be exploited or utilized without the prior written authority

of the Government.”

Subsection (b) above reads rather like a passage from past NRM legislation, in which Government

was the sole manager of natural resources and granted licences for commercial utilization. But it also

paves the way for the new generation of policies and laws which provide for the devolution of

management powers on the basis of legally binding management agreements (see chapters 6 (forestry)

and 7 (fisheries), below).

“5.-(1) Every person shall have a right to a clean and healthy environment.”

This section is not mere rhetoric. Subsections 5 (2) to 5 (4) provide individuals who believe this right

has been infringed by the actions of others with opportunity of seeking redress through the High Court

or complaining in writing to the Minister responsible for environmental affairs.

Section 6 states that the EMA does not over-ride the ongoing responsibilities or powers of lead

agencies within the various NRM sectors:

“6. Nothing in this Act shall be construed as divesting any lead agency of the powers, functions, duties or

responsibilities conferred or imposed on it by any written law relating to the protection and

management of the environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources or

limiting such powers, functions, duties or responsibilities.”

But …

“7. Where a written law on the protection and management of the environment and the conservation and

sustainable utilization of natural resources is inconsistent with any provision of this Act, that written law

shall be invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.”

In other words, in any conflict between the EMA and other sectoral NRM legislation, the EMA will

always take precedence. It is this provision that makes the EMA such a powerful tool for the

harmonization of E/NRM legislation. In practice much of the sectoral legislation has been or is being

revised after the enactment of the EMA, and considerable care has been taken to ensure that such

conflicts do not arise. Section 7 does not mean that the EMA is perfect, however, and it is envisaged

that once the Act has been in use for long enough for any shortcomings to become apparent it will

itself be amended accordingly.

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 4

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

Part III – Administration

This part of the Act, sections 8 to 20, lists the duties of the Minister, establishes the National Council

for the Environment (NCE) and the Technical Committee on the Environment and otherwise defines

the institutional context for environmental management. It establishes the post of Director of

Environmental Affairs and District Environmental Officers (EDOs – to distinguish them from District

Education Officers, or DEOs), and lists their principal responsibilities. Importantly, section 19 places

additional responsibilities on District Development Committees in relation to the environment.

In describing the duties of the Minister, section 8 really lays down the functions of the Environmental

Affairs Department:

“8.-(1) It shall be the duty of the Minister to promote the protection and management of the environment

and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources, and the Minister shall, in

consultation with lead agencies, take such measures as are necessary for achieving the objects of

this Act.

(2) without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing, the Minister shall –

(a) formulate and implement policies …

(b) co-ordinate and monitor all activities concerning the protection and management of the

environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources;

(c) prepare plans and develop strategies …, and facilitate co-operation between the Government,

local authorities, private sector and the public in the protection and management of the

environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources;

(d) initiate, facilitate or commission research and studies …;

(e) prepare and lay before the National Assembly at least once in every year a report on the state

of the environment;

(f) co-ordinate the promotion of public awareness …;

(g) monitor trends in the utilization of natural resources …;

(h) receive and investigate any complaint …;

(i) recommend to the Government … international or regional treaties, conventions or agreements

… to which Malawi should become party;

(j) promote international and regional co-operation …;

(k) … prescribe, by notice published in the Gazette, projects or classes or types of projects, for

which environmental impact assessment is necessary under this Act;

(l) … prescribe, by notice published in the Gazette, environmental quality criteria and standards ;

(m) carry out such other activities and take such other measures as may be necessary or

expedient for the administration and achievement of the objects of this Act. …”

Section 9 establishes the office of Director of Environmental Affairs (DEA) and “such other suitably

qualified public officers as may be required for the proper administration of this Act.” The DEA is responsible

to the Minister for the discharge of duties defined in the Act (under section 8, above), and is also

required to provide information or documents to the National Council for the Environment and to

brief the Council periodically on the status of the environment and natural resources.

The establishment of the NCE itself, and its functions, responsibilities and mode of operation are

detailed in sections 10 to 15. The Chairman of the NCE is appointed by the President, and its

membership includes the Secretary to the President and Cabinet (or his representative); all Principal

Secretaries (or their representatives); the General Managers of the Malawi Bureau of Standards and

the National Herbarium (or their representatives), one representative of the University of Malawi and

three members nominated by the Malawi Chamber of Commerce and Industry, environmental NGOs

and the National Council for Women in Development, respectively. The DEA acts as Secretary to the

NCE.

The NCE is required to meet at least four times each year. Its functions are described in section 12:

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 5

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

“12.– The Council shall –

(a) advise the Minister on all matters and issues affecting the protection and management of the

environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources;

(b) recommend to the Minister measures necessary for the integration of environmental

considerations in all aspects of economic planning and development;

(c) recommend to the Minister measures necessary for the harmonization of activities, plans and

policies of lead agencies and non-governmental organizations concerned with the protection

and management of the environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of

natural resources.”

Sections 16 to 18 deal with the establishment and operations of the Technical Committee on the

Environment (TCE). The TCE acts as a technical body to advise the NCE, and is composed of

recognized experts who are appointed by the Minister in their personal capacity. In practice, the TCE

spends much of its time considering and advising on environmental impact assessments produced by

prospective developers.

Sections 19 and 20 describe the responsibilities of District Development Committees and District

Environmental Officers, respectively. In brief, DDCs are assigned the duty to prepare a District

Environmental Action Plan (DEAP) once every five years, and a district state of the environment

report (DSOER) every two years (although many feel that this period should be revised upwards).

EDOs are required to guide the DDCs through both of these processes, and otherwise to act as

collectors and disseminators of environmental information, maintaining a flow of information in both

directions between national environmental institutions (the DEA, the NCE and the Minister) and the

public.

“19. A District Development Committee shall, in addition to its existing role-

(a) under the supervision of the District Environmental Officer, prepare every five years a district

environmental action plan;

(b) co-ordinate the activities of lead agencies and non-governmental organizations in the protection

and management of the environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural

resources in the district;

(c) promote and disseminate information relating to the environment through public awareness

programmes and prepare reports on the state of the environment in the district every two years at

least two months before the end of each second calendar year.”

“20.-(1) There shall be appointed for each district a District Environmental Officer who shall be a public

officer.

(2) The District Environmental Officer shall be a member of the District Development Committee and

shall-

(a) advise the District Development Committee on all matters relating to the environment and in

the performance of its functions under section 19;

(b) report to the Director on all matters relating to the protection and management of the

environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources;

(c) submit such reports to the Director as the Director may require;

(d) promote environmental awareness in the district on the protection and management of the

environment and the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources;

(e) gather and manage information on the environment and the utilization of natural resources in

the district; and

(f) perform such other functions as the Director may, from time to time, assign to him.”

These sections are discussed further under the heading Roles and responsibilities of district-level

public officers and institutions, on page 3:5.

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 6

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

Part IV – Environmental Planning

This Part of the EMA deals with national and district level environmental action plans. It is brief and

very clear, and is reproduced here in full:

“21. The Minister shall lay before the National Assembly a copy of the National Environmental Action Plan for

approval at its next meeting after the commencement of this Act and the Minister shall thereafter

review it every five years subject to approval by the National Assembly.

“22. The purpose of the National Environmental Action Plan shall be to promote and facilitate the integration

of strategies and measures for the protection and management of the environment into plans and

programmes for the social and economic development of Malawi. ”

“23.-(1) The district environmental action plan prepared under section 19 (a) shall-

(a) be in conformity with the National Environmental Action Plan;

(b) identify environmental problems in the district in question;

(c) be approved by the Minister on the recommendation of the Council; and

(d) be disseminated to the public by the District Development Committee.

(2) No person shall implement a development activity or project in any district otherwise than in

accordance with the district environment[al] action plan for the district in question.”

Part V – Environmental Impact Assessment, Audits and Monitoring

The system for environmental impact assessment is set out in sections 24 to 26 of the EMA:

“24.-(1) The Minister may, on the recommendation of the Council specify, by notice published in the

Gazette, the types and sizes of projects which shall not be implemented unless an environmental

impact assessment is carried out.

(2) A developer shall, before implementing any project for which an environmental impact assessment

is required under subsection (1), submit to the Director, a project brief stating in a concise

manner-

(a) the description of the project;

(b) the activities that shall be undertaken …

(c) the likely impact of those activities on the environment;

(d) the number of people to be employed …

(e) the segment or segments of the environment likely to be affected …

(f) such other matters as the Director may in writing require …”

“25.-(1) Where the Director considers that sufficient information has been stated in the project brief under

section 24, the Director shall require the developer, in writing, to conduct, in accordance with such

guidelines as the Minister may, by notice published in the Gazette prescribe, an environmental

impact assessment and to submit to the Director, in respect of such assessment, an environmental

impact report …

(3) The environment impact assessment report shall be open for public inspection…”

“26.-(1) Upon receiving the environmental impact assessment report, the Director shall invite written or oral

comments from the public thereon, and where necessary may-

(a) conduct public hearings … for the purpose of assessing public opinion thereon;

(b) require the developer to redesign the project … taking into account all the relevant

environmental concerns …

(c) require the developer to conduct a further environmental impact assessment of the whole

project or such part … as the Director may deem necessary;

(d) recommend to the Minister to approve the project subject to such conditions as the Director

may recommend to the Minister. …

(3) A licensing authority shall not license under any written law with respect to a project for which an

environmental impact assessment is required under this Act unless the Director has certified in

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 7

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

writing that the project has been approved by the Minister under this Act or that an environmental

impact assessment is not required under this Act.”

The sections above outline the basic steps to be taken by both a prospective developer and the

Government:

• scrutiny of the list of prescribed projects for which an EIA is or may be required (as published

in the EIA Guidelines of December 1997);

• submission of a Project Brief to the DEA;

• determination by the DEA of the adequacy of the Project Brief and the need for an EIA (and

in many cases the provision of technical advice on the Terms of Reference for an EIA);

• implementation of the EIA and submission of the EIA report to the DEA;

• public consultation on the EIA report, possibly resulting in a requirement for additional work;

• assessment of the adequacy of the EIA report (by the TCE), again with the possible

requirement for further modification;

• consideration of the final draft EIA report by the NCE, resulting in the Council’s

recommendation for approval (or otherwise by) the Minister, and

• Ministerial approval for the project to proceed.

Section 27 empowers the DEA to carry out or commission, in consultation with an appropriate lead

agency, periodic environmental audits of any project. An environmental audit is in essence a detailed

inspection, and its usual purpose is to ensure that a developer remains in compliance with the

measures agreed to mitigate any potentially adverse environmental impacts presented in an EIA

report. Under this provision the DEA may also require the developer to maintain and submit

appropriate records. Further, a developer is also obliged to take all reasonable measures to mitigate

undesirable environmental impacts that were not foreseen in the EIA.

Section 28 refers to projects that were already under way at the date that EIA became a legal

requirement: here the DEA is empowered to take such measures as are necessary to ensure that project

implementation complies with the provisions of the EMA.

Part VI – Environmental Quality Standards

Part VI – section 30 – allows the Minister to prescribe environmental quality standards, for example

for air, water, soil, noise, vibrations, radiation, effluent and solid waste. Such standards are to be

based on scientific principles, should take into account the practical issues of ensuring compliance,

and may varied geographically within Malawi.

Part VII – Environmental Management

Part VII of the EMA gives the Minister powers to undertake three kinds of action in support of

E/NRM. Section 31 provides for the “determination of fiscal incentives”. Section 32 gives the Minister to

declare any area which is in need of special protection and which is not already a National Park,

Wildlife Reserve or Forest Reserve to be an “environmental protection area”. Under section 33 the

Minister is given the power to prevent or arrest any act which has or is likely to have adverse

environmental consequences by issuing an “environmental protection order” against the person or

persons responsible. An environmental protection order may in addition require the payment of

compensation “to any person whose land is degraded by the action or conduct of the person against whom the

environmental protection order is made.” Section 33 gives the DEA (and, by delegation, his staff)

extensive powers of entry and inspection, and specifies the right of a person on whom an

environmental protection order is served to appeal to the Tribunal established under section 70 (see

Part XII, below).

Sections 35 to 41 accord to the Minister the power to make rules and regulations and otherwise

exercise control over various matters including the conservation of biological diversity, access to

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 8

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

genetic resources, waste management, including the import and export of hazardous waste, the

classification of pesticides and other hazardous substances and the protection of the ozone layer.

Part VIII – Pollution Control

Sections 42 to 44 provide for controls over effluent discharges and gaseous emissions, but do allow

the licensing of such activities under conditions defined by the Minister. Section 44 is particularly

short and simple:

“44. No person shall pollute or permit or cause any other person to pollute the environment.”

Part IX – Inspection, Analysis and Records

Sections 45 to 47 specify the powers of environmental inspectors as agents for ensuring compliance

with the provisions of the EMA. Inspectors are required to carry identity cards, which must be

produced on request, and are accorded powers of entry, access to relevant records and documents and

also the power to take samples for analysis. The designation of approved laboratories, the

appointment of analysts and the form of certification for analytical results are detailed in sections 48

to 50.

Section 51 empowers the DEA to require, through publication in the Gazette, the maintenance and

regular submission of records for certain kinds of activity, for the purposes of environmental auditing

and monitoring. Section 52 defines the public nature of such information, save in instances where the

information is of a proprietary or commercially sensitive nature.

Part X – Environmental Fund

Part X of the EMA, sections 53 to 60, establishes and lays down a procedural framework for the

Environmental Fund, a fund to be used at the discretion of the Minister for the protection of the

environment and to support the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources. The fund

may be financed by Parliamentary appropriations, advances from the Ministry of Finance, voluntary

contributions and “fees or other penalties in respect of licenses issued under this Act”.

Although several other mechanisms for financing environmental initiatives are in preparation,

including the Malawi Environmental Endowment Trust, the Environmental Fund will remain

independent of these and may be used to finance any action or venture which the Minister considers

important. The Fund accounts will be maintained in accordance with the Finance and Audit Act, and

will be audited by the Auditor General.

Part XI – Offences

Sections 61 to 67 define various offences under the EMA and specify a wide range of penalties up to a

maximum of K1,000,000 and imprisonment for ten years.

Part XII – Legal Proceedings

Section 68 confers immunity from legal proceedings to the Minister, the DEA, environmental

inspectors, analysts or any others to whom authority under the EMA has been delegated in respect of

anything done in good faith under the provisions of the Act.

Sections 69 to 74 establish an Environmental Appeals Tribunal to which anyone aggrieved by

decisions or actions taken under the EMA may appeal. Typical examples might include developers

whose projects have been rejected on the basis of an environmental impact assessment, or individuals

who believe themselves to have been unfairly treated in respect of an environmental protection order.

The Tribunal will comprise three technically knowledgeable individuals appointed by the President on

the recommendation of the Minister, and decisions will be by simple majority.

Section 75 specifies that in the case of an offence committed by a corporate body, all directors and

similar office bearers (or in the case of a partnership each partner) will be deemed guilty of the

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 9

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

offence, unless an individual can prove that he was unaware of the offending act or had attempted to

prevent it.

Part XIII – Miscellaneous Provisions

This final part of the EMA consists of only two sections. Section 76 gives the DEA powers to close

any premises which he reasonably believes to have been used in contravention of the Act. Section 77

states that the Minister may make regulations for the better carrying out of the purposes of the Act.

Environmental Affairs Department 2: 10

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

3. DECENTRALIZATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES

MANAGEMENT

Framework Documents Key dates

Principal statute: The Local Government Act, 1998 December, 1998

Subsidiary legislation:

Policy document: The National Decentralization Policy October, 1998

Other publications: Malawi: Decentralization Policy August 1996

Implementation (Capacity Assessment and

Resource Needs Study). GoM/UNDP

3.1 THE NATIONAL DECENTRALIZATION POLICY (1998) AND THE LOCAL

GOVERNMENT ACT (1998)

3.1.1 Approach

The National Decentralization Policy (NDP) will, when fully implemented, transform not only what

has traditionally been thought of as district administration, but also many of the functions which until

now have been the responsibility of central Government institutions. This section of the manual

explains the structure and functions of the future decentralized administration and its relationship to

the technical Departments and Ministries of central Government. The emphasis here is on

administrative changes which have general implications for environment and natural resources

management, and large parts of the Local Government Act (LGA) – for instance Parts VI, which deals

with financial provisions, and VII, which deals with valuation and rating – are not discussed in any

detail. As far as possible the explanation provided here makes use of verbatim extracts from the

Policy (Univers Condensed Font Size 10) and the Act (Tahoma Font Size 9), and any other

documents used to assist in interpretation are quoted by source. The following section discusses more

specific issues affecting the roles of public officers and other professionals working in natural

resources management at district level, and explores the framework defined jointly by the Local

Government Act and the Environment Management Act.

3.1.2 Objectives of the decentralization policy

“The policy:-

(a) devolves administration and political authority to the district level;

(b) integrates governmental agencies at the district and local levels into one administrative unit, through the process of

institutional integration, manpower absorption, composite budgeting and provision of funds for the decentralised

services; …” [NDP section 2 – The Policy]

“The objectives of local government shall be to further the constitutional order based on democratic

principles, accountability, transparency and participation of the people in decision-making and development

processes.” [LGA section 3.]

3.1.3 New structures at district level

“The new local government system will be made up of District Assemblies. Cities and Municipalities will be “districts in their

own right”. The District Assemblies will have powers to create committees at Area, Ward or Village level for purposes of

facilitating participation of the people in the Assembly’s decision making.” [NDP section 4 – Structure of the New Local

Government System]

The District Assembly will be the new instrument of democratic local government, and will consist of

one elected member from each ward in the local government area; Traditional Authorities and Sub-

Environmental Affairs Department 3: 1

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

Traditional Authorities (who shall not have voting powers), members of Parliament (also non-voting)

and five non-voting persons to be appointed by the Assembly to cater for the interests of special

interest groups. The Assembly will be served by a Secretariat: a body of public officers headed by a

Chief Executive and responsible for implementing the resolutions of the Assembly and performing its

day to day executive and administrative functions. The Secretariat will incorporate Government

departments responsible for providing services within the district, including public amenities,

education, health, water and various rural extension services. This is a fundamental change from the

present system: heads of departments at district level will in future be the direct subordinates of the

Chief Executive, not of their parent Ministries. Since the Chief Executive is himself directed by the

elected Assembly, the new system will for the first time render public servants directly accountable to

the population they serve.

Sections 5 to 13 of the LGA deal with the constitution and proceedings of the Assembly, including

membership, functions, the election of office-bearers, the procedure for holding meetings (including

the requirement for a one-third quorum of elected members) and disclosure of interest.

3.1.4 Functions of the District Assembly

Section 6 of the LGA lists the functions of the Assembly as follows:

“6.-(1) The Assembly shall perform the following functions –

(a) to make policy and decisions on local governance and development for the local government

area;

(b) to consolidate and promote local democratic institutions and democratic participation;

(c) to promote infrastructural and economic development through the formulation, approval and

execution of district development plans;

(d) to mobilize resources within the local government area for governance and development;

(e) to maintain peace and security in the local government area in conjunction with the Malawi

Police Service;

(f) to make by-laws for the good governance of the local government area; …”

The Second Schedule to the LGA lists certain additional functions, some of them normally associated

with local government authorities, others more often seen as tasks of central government. The

marginal note for section 2 of the Second Schedule is “Environmental protection”, but most of this

section is concerned with issues of sanitation and public health. However, sub-section 2 (6) makes

specific reference to river pollution and streambank cultivation:

“2.-(6) Subject to the provisions of any other written law, an Assembly shall be responsible for the draining,

cleansing and sanitation of its area and the prohibition and control of pollution of any water in any

river or stream and for this purpose may prohibit or regulate the use of any such river or stream

and any river-bank or streambank including any cultivation therein or the extraction of any sand,

gravel or other material therefrom.”

Sections 3 to 20 of the Second Schedule deal with a wide variety of matters ranging from public

health to roads, emergency services, building regulations and planning. Section 21 outlines the

requirement for district development planning, including specific reference to environmental

planning. Section 21 is clearly compatible with section 19 of the EMA, which requires the District

Development Committee to prepare 5-yearly District Environmental Action Plans:

“21.-(1) An Assembly shall have a duty to draw up plans for the social, economic and environmental

development of the area for such periods and in such form as the Minister may prescribe.

(2) Development plans shall be prepared in conjunction and consultation with other agencies having a

public responsibility for or charged with producing plans for development whether generally or

specifically and affecting the whole or a substantial part of the Assembly.”

Section 22 is of particular importance, as it lists those functions of central Government which will be

transferred to the control of District Assemblies:

“22. The Assembly shall perform the following functions – …

Environmental Affairs Department 3: 2

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1

(e) taking charge of all decentralized services and activities which include but are not limited to-

(i) crop, animal and fisheries husbandry extension services; …

(vii) district planning;

(viii) local government development planning;

(ix) land administration; …

(xii) forests and wetlands; …

(f) regulate, control, manage, administer, promote and licence any of the things or services which

the Assembly is empowered or required to do, and establish, maintain, carry on, control,

manage or administer and prescribe the forms in connection therewith to fix fees or charges to

be levied in that respect; …

(g) assist government to preserve the environment through protection of forests, wetlands, lake

shores, streams and prevention of environmental degradation; …”

Under section 6 of the LGA, sub-section (3) allows the Minister to exempt District Assemblies from

any of the functions listed in the Second Schedule if they so request, and sub-section (4) allows the

Minister to amend the Second Schedule.

3.1.5 Working modalities

Part IV of the LGA (sections 14 to 23) sets out how the District Assemblies will discharge their

functions. Much of this part is concerned with the establishment of working (or service) committees:

“14.-(1) The Assembly shall establish the following committees-

(a) the Finance Committee;

(b) the Development Committee;

(c) the Education Committee;

(d) the Works Committee;

(e) the Health and Environment Committee; and

(f) the Appointments and Disciplinary Committee.

(2) The Assembly may establish other committees at a local government area level.

(3) The Assembly may establish such other committees at ward, area or village level as it may

determine.

(4) The composition of service committees and the committees established under subsections (2) and

(3) shall be determined by the Assembly.

(5) A service committee or other committee established under subsections (2) and (3) may in its

discretion at any time and for any period invite any person to attend any meeting of such

committee and take part in the deliberations at the meeting, but such person shall not be entitled

to vote at the meeting.”

Note that the composition of the committees is left for the Assembly itself to determine. Committees

may appoint sub-committees, and unless directed otherwise by the Assembly may arrange for specific

functions to be delegated to sub-committees or to individual officers. Two or more Assemblies may

decide to discharge certain functions jointly, and under sections 15 and 16 of the LGA are empowered

to appoint joint committees for this purpose.

Although the Assembly represents its electorate and has considerable freedom to determine its own

affairs, it is not permitted to take actions which are unlawful or run contrary to national policies;

neither is it permitted run at a financial loss beyond approved borrowing. Under section 20 the Chief

Executive has a responsibility to monitor the decisions of the Assembly and to bring to the

Assembly’s attention any proposed course of action which might be improper. Further, the Minister

responsible for Local Government is empowered under section 21 to order an Assembly to desist from

an improper course of action and, in the event of non-compliance with such an order, to suspend the

Assembly pending a judicial review by the High Court. If in such circumstances the High Court

Environmental Affairs Department 3: 3

NRM Policies, Laws and Institutional Framework in Malawi – Volume 1