Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ooi 150107

Caricato da

NilaFitriOlaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ooi 150107

Caricato da

NilaFitriOlaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research

Original Investigation

Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric

vs Adult Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Morgan K. Richards, MD, MPH; John P. Dahl, MD, PhD, MBA; Kenneth Gow, MD; Adam B. Goldin, MD, MPH;

John Doski, MD; Melanie Goldfarb, MD; Jed Nuchtern, MD; Monica Langer, MD; Elizabeth A. Beierle, MD;

Sanjeev Vasudevan, MD; Douglas S. Hawkins, MD; Sanjay R. Parikh, MD

CME Quiz at

IMPORTANCE Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is endemic in some Asian regions but is jamanetworkcme.com and

CME Questions page 304

uncommon in the United States. Little is known about the racial, demographic, and biological

characteristics of the disease in pediatric patients.

OBJECTIVES To improve understanding of the differences between pediatric and adult NPC

and to determine whether race conferred a survival difference among pediatric patients

with NPC.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This retrospective cohort study included all 17 317

patients with a primary diagnosis of NCP in the National Cancer Data Base from January 1,

1998, to December 31, 2011. Of these, 699 patients were 21 years or younger (pediatric);

16 618 patients, older than 21 years (adult). Data were analyzed after data collection.

EXPOSURE Pediatric age at diagnosis of NPC.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Demographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics of

pediatric patients with NPC were compared with those of adults using the χ2 test for

categorical variables. An adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to

examine survival differences in pediatric patients relative to adult patients. In addition, the

risk for pediatric mortality by race was estimated.

RESULTS Of the 17 317 patients, a total of 699 pediatric and 16 618 adult patients were

identified with a primary diagnosis of NPC (female, 239 pediatric patients [34.2%] and 5153

adult patients [32.4%]). Pediatric patients were most commonly black (299 of 686 [43.6%]),

whereas adults were most likely to be non-Hispanic white (9839 of 16 504 [60.0%];

P < .001). Pediatric patients were less likely to be Asian (39 of 686 [5.7%]) than were adults

(3226 of 16 405 [19.7%]; P < .001). Pediatric patients were more likely to have regional nodal

evaluation and to present with stage IV disease (227 of 643 [35.3%] and 330 of 565 [58.4%],

respectively) than were adult patients (3748 of 15 631 [24.0%] and 6553 of 13 721 [47.8%],

respectively; P < .001 for both comparisons). Pediatric patients had a lower risk for mortality

relative to adults (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.25-0.56). No difference in mortality by racial

group was found among pediatric patients (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.82-1.40).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Pediatric patients with NPC were more commonly black and

presented more frequently with stage IV disease. Pediatric patients had a decreased mortality

risk relative to adults, even after adjusting for covariables. Asian race was not associated with

increased mortality in pediatric patients with NPC. Racial differences are not associated with

an increased risk for mortality among pediatric patients.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author: Morgan K.

Richards, MD, MPH, Division of

Pediatric General and Thoracic

Surgery, Department of General and

Thoracic Surgery, Seattle Children’s

JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(3):217-222. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3217 Hospital, 4800 Sand Point Way NE,

Published online January 14, 2016. PO Box OA.9.220, Seattle, WA 98105.

217

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Research Original Investigation Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

N

asopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a rare malignant tu- pared with adults older than 21 years. All of the data made

mor derived from the epithelium lining the nasophar- available to us by the NCDB ranged from January 1, 1998, to

ynx. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifi- December 31, 2011. No duplicate cases were included in the

cation system for NPC characterizes the tumors based on the analysis. This study was approved by the institutional

following 3 primary histopathologic subtypes: keratinizing review board of the Seattle Children’s Hospital. Because data

squamous cell carcinoma (type I), nonkeratinizing differenti- were deidentifed, informed consent was waived.

ated carcinoma (type II), and nonkeratinizing undifferenti-

ated carcinoma (type III).1 Clinical Covariates and Measures

The pathogenesis of NPC is related to a number of genetic Patient demographics included sex, race, insurance status,

and environmental factors. Subtypes of HLA antigens, chro- household income, educational level, and rural vs urban

mosomal deletions affecting tumor suppressor genes, and a place of residence (Table 1). Race was documented by the

polymorphism of the CYP2E1 gene have all been associated with trained abstractors based on the medical record and based on

an increased risk for developing NPC. 2 Infection with the Ep- standardized classifications within the NCDB data dictionary

stein-Barr virus is the most common environmental factor as- (http://ncdbpuf.facs.org/node/259). Race was assessed in this

sociated with the pathogenesis of types II and III NPC.2 Addi- study because previous reports of unequal racial distribu-

tional environmental risk factors include tobacco smoking and tions of NPC among adult patients have been made. 12-14

exposure to preserved foods, formaldehyde, and wood dust.2 Whether this racial distribution is the same or different in

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is endemic to southern China, children has yet to be determined. Insurance status was

Southeast Asia, northern Africa, and the Arctic region; NPC is defined as private, governmental, or uninsured. Household

much less common in Japan and the western hemisphere. In income was divided into quartiles based on the patient’s

endemic areas, the incidence of NPC has a unimodal age dis- home zip code. Educational level was based on the percent-

tribution with a peak from 50 to 60 years of age.3 In the Medi- age of high school graduates in the patient’s home zip code.

terranean countries and in select North American popula- Rural vs urban place of residence was based on population

tions, a bimodal age distribution has a minor peak from 10 to density and proximity to a metropolitan area.

20 years of age and a second peak from 40 to 60 years of age.3 Tumor features included stage of disease, tumor behav-

In the United States, adults of Chinese descent have the high- ior, tumor grade, and the presence of positive or negative

est rates of NPC, followed distantly by other ethnic groups, with margins at surgical resection. Disease staging was based on

persons of European descent at the lowest rates of NPC.4 Na- the National Comprehensive Cancer Network TNM classi-

sopharyngeal cancer is 2 to 3 times more common in males than fication.15 Tumor behavior was described as in situ or inva-

females, irrespective of race/ethnicity.5 In endemic areas, lower sive, whereas tumor grade was categorized as well differenti-

socioeconomic status is associated with a higher risk for NPC.6-8 ated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or

In the western hemisphere, NPC is exceedingly rare in chil- undifferentiated.15

dren and adolescents; the annual incidence of NPC inthe United Treatment factors included nodal evaluation and margin

States has been estimated to be 0.5 per 1 million children. 9 The status. Nodal evaluation was categorized as performed or not

WHO type III is the most common pathologic subtype of NPC performed. Margin status was defined as positive or negative.

in children, irrespective of geographic location or race/ In addition, the types of treatment received, including radio-

ethnicity, and the median age at NPC diagnosis in children is therapy, chemotherapy, and operative intervention, were

13 years.4,10 As with adults, the incidence of NPC in children is compared between pediatric and adult patients with NPC.

highest in boys; however, the highest rates of NPC in persons

younger than 20 years are in the black population. 4,10,11 Statistical Analysis

Although the demographic distribution and outcomes re- Data were analyzed after data collection. To perform the

lated to NPC in children and adolescents younger than 20 years analyses, pediatric patients 21 years or younger were com-

in the United States are known, the characteristics of NPC and pared with the adult population using univariate statistics

associated socioeconomic factors are less well described.11 The with the χ2 test for categorical data (P < .05). An adjusted Cox

purpose of the present study was to use the National Cancer proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate

Data Base (NCDB) to examine such characteristics of NPC survival differences between the 2 groups. To account for the

among pediatric patients. Our primary hypothesis was that, as increased risk for mortality due to non-NPC causes among

with endemic areas, NPC in persons 21 years or younger in the older patients, estimated survival was compared between the

Unites States would be associated with factors implying a lower 2 groups with the adult patient group restricted to patients

socioeconomic status. younger than 60 years. Finally, we stratified the pediatric

group by race, and survival was again estimated using an

adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model. Adjust-

ment factors were determined a priori and included sex,

Methods income, education, race, insurance status, urban vs rural

Study Population place of residence, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity index (http:

We used the NCDB to perform a retrospective cohort study //ncdbpuf.facs.org/content/charlsondeyo-comorbidity-index),

of pediatric and adult patients with NPC in the United States. tumor grade, and disease stage. Statistical analysis was com-

Pediatric patients from birth to 21 years of age were com- pleted using STATA software (version 12; StataCorp LP).

218 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery March 2016 Volume 142, Number 3 jamaotolaryngology.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Original Investigation Research

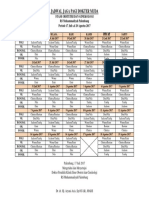

Table 1. Demographic, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics for Patients With NPC

Patient Group, No./Total No. (%)a

Pediatric Adult

Characteristic (n = 699) (n = 16 618) P Value

Demographic and health

Female 239/699 (34.2) 5153 (31.0) .08

Race

White 265/686 (38.6) 9839/16 405 (60.0)

Black 299/686 (43.6) 2249/16 405 (13.7)

<.001

Asian 39/686 (5.7) 3226/16 405 (19.7)

Other 83/686 (12.1) 1091/16 405 (6.7)

Insurance status

Private 336/664 (50.6) 7960/15 751 (50.5)

Government 278/664 (41.9) 6641/15 751 (42.2) .97

Uninsured 50/664 (7.5) 1150/15 751 (7.3)

Median household income, $

<30 000 209/665 (31.4) 2552/15 692 (16.3)

30 000-35 000 133/665 (20.0) 2985/15 692 (19.0)

<.001

35 000-45 999 155/665 (23.3) 4328/15 692 (27.6)

≥46 000 168/665 (25.3) 5827/15 692 (37.1)

Adults in patient’s zip code with no high school diploma, %

≥29 240/665 (36.1) 3628/15 691 (23.1)

20.0-28.9 165/665 (24.8) 3935/15 691 (25.2)

<.001

14.0-19.9 121/665 (18.2) 3441/15 691 (21.9)

<14.0 139/665 (20.9) 4687/15 691 (30.0)

Place of residence by population

Metro ≥1 million 374/666 (56.2) 9116/15 627 (58.3)

Metro 250 000 to 1 million 116/666 (17.4) 2760/15 627 (17.7)

.01

Metro <250 000 or adjacent to metro 128/666 (19.2) 3059/15 627 (19.6)

Urban or rural <20 000 and not adjacent to metro 48/666 (7.2) 692/15 627 (4.4)

Charlson/Deyo comorbidity index

0 445/462 (96.3) 9325/10 900 (85.6)

1 17/462 (3.7) 1235/10 900 (11.3) <.001

≥2 0 340/10 900 (3.1)

Tumor

Invasive 699 (100) 16 557/16 618 (99.6) .11

Grade

Well differentiated 6/528 (1.1) 513/12 192 (4.2)

Moderately differentiated 12/528 (2.3) 2229/12 192 (18.2)

<.001

Poorly differentiated 146/528 (27.7) 5941/12 192 (48.7)

Undifferentiated 364/528 (68.9) 3509/12 192 (28.8)

Stage

0 1/565 (0.2) 76/13 721 (0.6)

I 20/565 (3.5) 1335/13 721 (9.7)

II 41/565 (7.3) 1753/13 721 (12.8) <.001

III 173/565 (30.6) 4004/13 721 (29.2)

IV 330/565 (58.4) 6553/13 721 (47.8)

WHO classification

Abbreviations: metro, metropolitan;

Keratinizing SCC (type I) 81/435 (18.6) 7838/12 170 (64.4)

NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma;

Nonkeratinizing SCC (type II) 83/435 (19.1) 2020/12 170 (16.6) <.001 SCC, squamous cell carcinoma;

Undifferentiated SCC (type III) 271/435 (62.3) 2312/12 170 (19.0) WHO, World Health Organization.

a

Treatment Denominators do not sum to

column totals because of missing

Re gional node examination

data. Percentages have been

Not performed 416/643 (64.7) 11 883/15 631 (76.0) rounded and may not total 100.

<.001

Performed 227/643 (35.3) 3748/15 631(24.0) Pediatric patients are 21 years or

Positive surgical margin 22/699 (3.1) 556/16 618 (3.3) .21 younger; adult patients, older than

21 years.

jamaotolaryngology.com JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery March 2016 Volume 142, Number 3 219

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Research Original Investigation Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

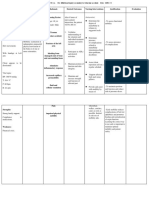

Table 2. Differences in Treatment Modalities for Pediatric and Adult Patients With NPC

Patient Group, No./Total No. (%)a

Pediatric Adult

Treatment Modality (n = 699) (n = 16 618) P Value

Type of treatment

None 26/691 (3.8) 1513/16 258 (9.3)

Radiotherapy alone 19/691 (2.7) 1945/16 258 (12.0) Abbreviation: NPC, nasopharyngeal

Chemotherapy alone 3/691 (0.4) 110/16 258 (0.7) <.001 carcinoma.

a

Radiotherapy + chemotherapy (any type) 562/691 (81.3) 10 444/16 258 (64.2) Denominators do not sum to

Surgical excision or resection 81/691 (11.7) 2246/16 258 (13.8) column totals because of missing

data. Percentages have been

Chemotherapy regimen rounded and may not total 100.

Radiotherapy + single-agent chemotherapy 98/514 (19.1) 3578/9521 (37.6) Pediatric patients are 21 years or

<.001

Radiotherapy + multiple-agent chemotherapy 416/514 (80.9) 5943/9521 (62.4) younger; adult patients, older than

21 years.

pediatric patients were stratified by race, no difference was seen

Results in mortality by race (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% CI 0.82-1.40)

(Table 3 and Figure 2).

We identified a total of 17 317 patients as having a primary di-

agnosis of NPC, including 699 pediatric patients and 16 618 adult

patients. We found no difference between pediatric and adult

Discussion

patients in terms of their sex distribution (239 female pediat-

ric patients [34.2%] 5153 female adult patients [31.0%]; P = .08). The present study confirms that in the United States, the demo-

In addition, we found no difference with regard to insurance graphic distribution of NPC differs between the pediatric and

status between groups (P = .97). Pediatric patients had a sig- adult populations. Using the NCDB population of 699 persons

nificantly different racial profile relative to adult patients, with 21 years and younger with a diagnosis of NPC, we found that

a predominance of black patients (299 of 686 [43.6%]) com- relative to adults, NPC in pediatric patients is more common

pared with adults, among whom white race was more com- in black patients and relatively rare in Asians. Richey et al11 and

mon (9839 of 16 405 patients [60.0%]; P < .001). Pediatric pa- Sultan et al9 previously used a different data source, the Na-

tients were significantly less likely to be of Asian race (39 of 686 tional Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Re-

[5.7%]) than were adults (3226 of 16 405 [19.7%]; P < .001) sults (SEER) tumor registry, to examine the population demo-

(Table 1). Pediatric patients were more likely to live in a rural graphics for persons with NPC in the United States. The study

area, in an area with lower median household income, and in by Richey et al11 identified 160 patients younger than 20 years

an area of lower educational achievement relative to adult pa- with a diagnosis of NPC and demonstrated that the incidence

tients (P = .01, P < .001, and P < .001, respectively) (Table 1). of NPC was 1.61 per 1 million for black individuals and 0.95 per

Pediatric patients were more likely to present with an un- 1 million for Asian and other races. The study by Sultan et al9

differentiated tumor (364 of 528 [68.9%]) than adult patients of 129 pediatric patients younger than 20 years and 5885 adults

(3509 of 12 192 [28.8%]; P < .001). Pediatric patients were also found an incidence of 0.5 per 1 million person-years in pedi-

more likely to present with stage IV disease (330 of 565 [58.4%]) atric patients and 8.4 per 1 million person-years in adults. The

than adult patients (6553 of 13 721 [47.8%]; P < .001), although present study uses different statistical methods and agrees with

there was no difference in positive margin status at resection. the results presented by Richey et al,11 but it includes a much

Pediatric patients had more undifferentiated squamous cell tu- larger population of children with a diagnosis of NPC. Both pre-

mors (WHO type III) (271 of 435 [62.3%]) relative to adult pa- vious studies failed to demonstrate any differences in NPC-

tients (2312 of 12 170 [19.0%]; P < .001). Pediatric patients were related mortality among the different ethnic populations.

more likely to undergo nodal sampling at the time of resection Data from the NCDB also demonstrate that pediatric pa-

(227 of 643 [35.3%]) relative to adult patients (3748 of 15 631 tients presenting with NPC tend to live in a rural area, in an

[24.0%]; P < .001) (Table 1). In addition, pediatric patients were area with a lower median income, or in an area with lower edu-

more likely to undergo radiotherapy and chemotherapy than cational achievement. These findings are consistent with pre-

adult patients. Pediatric patients more frequently received mul- vious findings indicating that NPC is more common in adults

tiple-agent chemotherapy than did adult patients, who more of- of lower socioeconomic status.12 Given these findings, we can

ten received single-agent therapy (P < .001) (Table 2). hypothesize that pediatric patients with NPC in such areas may

Compared with adults, NPC-related mortality was de- be at increased risk for developing NPC owing to environmen-

creased more than 60% among pediatric patients, based on Cox tal exposures, such as tobacco smoke or preserved foods. How-

proportional hazards regression analysis (hazard ratio, 0.37; ever, tobacco exposure is most commonly associated with type

95% CI 0.25-0.56) (Table 3 and Figure 1). When the adult popu- I NPC, which is the least common type of NPC in children. In

lation was restricted to patients younger than 60 years, again addition, the method of food preservation closely associated

NPC-related mortality was nearly 60% less likely among pe- with the development of NPC is most commonly used in tra-

diatric patients (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% CI 0.27-0.63). When ditional southern Chinese culture.12 The development of NPC

220 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery March 2016 Volume 142, Number 3 jamaotolaryngology.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Original Investigation Research

Table 3. Adjusted Mortality Risk Comparing Pediatric and Adult Patients Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates for Pediatric Patients With

With NPC Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma by Race

Pediatric Patient Group Comparisona Risk for Mortality, HR (95% CI)b 100

All adults aged >21 y 0.37 (0.25-0.56)

Adults aged 21-60 y 0.41 (0.27-0.63)

Surviving Patients, %

75

Stratified by race 1.10 (0.82-1.40)

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 50

a White

Pediatric patients are 21 years or younger; adult patients, older than 21 years. Black

b

Adjusted for sex, income, educational level, race, insurance, urban vs rural 25 Asian

place of residence, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity index, tumor grade, and tumor Other

stage, described in Table 1. 0

0 5 10 15

Time Since Diagnosis, y

No. at risk

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates for Pediatric and Adult

White 168 119 25 0

Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Black 183 100 29 0

Asian 26 16 4 0

100 Other 48 30 7 0

Pediatric patients Pediatric patients include those 21 years or younger.

75

Surviving Patients, %

significantly more likely to undergo radiotherapy and chemo-

50

therapy. The more aggressive treatment regimens may have

contributed to an overall improved survival.

25

An important strength of this study is the large number of

Adult patients

pediatric patients. The NCDB is a hospital-based registry that

0

0 5 10 15

captures approximately 70% of all new cancer cases, includ-

Time Since Diagnosis, y ing 42% of childhood cancers in the United States.16 Data cap-

No. at risk ture began in 1989 and now includes more than 30 million

Pediatric patients 432 268 66 0

Adult patients 10466 4399 984 0 records.16 However, some limitations to this study must be

noted. First, owing to limitations in database coding, we are

Pediatric patients include those 21 years or younger; adult patients, older than unable to distinguish between disease-specific and all-cause

21 years. mortality, which is important when comparing adult and pe-

diatric patient populations. We attempted to mitigate this limi-

in the pediatric population in the United States may be re- tation byrestricting that analysis to younger adult patients (<60

lated to Epstein-Barr virus infection or a specific genetic pre- years) and by controlling for adult comorbidities. Second, dis-

disposition found more commonly in the black population. ease incidence could not be calculated because the NCDB does

Our results indicate that persons 21 years or younger with not capture a representative sample of the population. Fi-

NPC in the United States more frequently present with undif- nally, facility identification information was not available, so

ferentiated tumors and more advanced disease. This finding we could not determine whether patients were treated at adult

is consistent with those of previous studies focusing on the or pediatric institutions. These data may have been useful in

population characteristics of NPC in the United States and in evaluating for differences in treatment practices. Long-term

endemic areas. Sultan et al9 noted in the SEER database that follow-up data regarding second malignant neoplasms after ra-

children were more likely to present with advanced disease. diotherapy may be limited in this data set.

One recent study by Yan et al13 examined the characteristics

of NPC in children and adolescents at a large cancer center in

southern China and found that more than 90% of patients with

Conclusions

NPC who were younger than 21 years had stage III or stage IV

disease at presentation. Despite the fact that children with NPC Although uncommon, pediatric NPC appears to affect a dif-

tend to have less differentiated, more advanced tumors, these ferent patient demographic relative to adult NPC. Nasopha-

patients have a lower risk for all-cause mortality relative to ryngeal carcinoma in children is associated with rural loca-

adults with NPC. The improved survival may have been re- tion, low socioeconomic status, and more advanced disease

lated to the presence of less morbidity in the pediatric popu- at presentation. Despite these differences, pediatric NPC is as-

lation relative to the adults; however, pediatric patients were sociated with a lower mortality rate than adult disease.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Published Online: January 14, 2016. Department of General and Thoracic Surgery,

Submitted for Publication: August 19, 2015; final doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3217. Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington

revision received October 31, 2015; accepted Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, (Richards, Gow, Goldin); Department of

November 11, 2015. University of Washington, Seattle (Richards); Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery,

Division of Pediatric General and Thoracic Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle (Dahl, Parikh);

jamaotolaryngology.com JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery March 2016 Volume 142, Number 3 221

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Research Original Investigation Factors Associated With Mortality in Pediatric Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Division of Pediatric Surgery, Methodist Children’s REFERENCES nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children and adults:

Hospital of South Texas, San Antonio (Doski); 1. Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint a SEER study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(2):

Department of Surgery, John Wayne Cancer Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC 279-284.

Institute, Santa Monica, California (Goldfarb); cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann 10. Pinkerton CR, Plowman PN. Rare tumors. In:

Division of Pediatric Surgery, Baylor College of Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471-1474. Pinkerton CR, Plowman PN, eds. Paediatric Oncology.

Medicine, Houston, Texas (Nuchtern, Vasudevan); 2nd ed. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1997:

Department of Pediatric General Surgery, Maine 2. Spano JP, Busson P, Atlan D, et al.

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas: an update. Eur J Cancer. 561-575.

Children’s Cancer Program, Portland (Langer);

Department of Pediatric General Surgery, 2003;39(15):2121-2135. 11. Richey LM, Olshan AF, George J, et al. Incidence

University of Alabama, Birmingham (Beierle); Fred 3. Berry MP, Smith CR, Brown TC, Jenkin RD, Rider and survival rates for young blacks with

WD. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the young. Int J nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States. Arch

Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Department of

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980;6(4):415-421. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(10):1035-1040.

Pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of

Washington, Seattle (Hawkins). 4. Ayan I, Altun M. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in 12. Yu MC, Yuan J-M. Epidemiology of

Author Contributions: Drs Richards and Gow had children: retrospective review of 50 patients. Int J nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol.

full access to all the data in the study and take Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35(3):485-492. 2002;12(6):421-429.

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the 5. Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Raymond L, 13. Yan Z, Xia L, Huang Y, Chen P, Jiang L, Zhang B.

accuracy of the data analysis. Young J, eds. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Vol Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children and

Study concept and design: Richards, Gow, Goldin, 7. Lyon, France: IARC Scientific; 1997. adolescents in an endemic area: a report of 185

Nuchtern, Langer, Vasudevan, Parikh. cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(9):

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: 6. Yu MC, Ho JH, Ross RK, Henderson BE. 1454-1460.

Richards, Dahl, Gow, Doski, Goldfarb, Beierle, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Chinese: salted fish

or inhaled smoke? Prev Med. 1981;10(1):15-24. 14. Luo J, Chia KS, Chia SE, Reilly M, Tan CS, Ye W.

Hawkins, Parikh. Secular trends of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Drafting of the manuscript: Richards, Dahl, Gow, 7. Sriamporn S, Vatanasapt V, Pisani P, incidence in Singapore, Hong Kong and Los Angeles

Goldin, Hawkins, Parikh. Yongchaiyudha S, Rungpitarangsri V. Environmental Chinese populations, 1973-1997. Eur J Epidemiol.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: 2007;22(8):513-521.

intellectual content: All authors. a case-control study in northeastern Thailand.

Statistical analysis: Richards, Goldin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1(5):345-348. 15. Pfister DG, Spencer S, Brizel DM, et al. Head and

Administrative, technical, or material support: Gow, Neck Cancers, Version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc

8. Jeannel D, Hubert A, de Vathaire F, et al. Diet, Netw. 2015;13(7):847-855.

Goldin, Nuchtern. living conditions and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in

Study supervision: Gow, Goldin, Goldfarb, Tunisia--a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1990;46 16. Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY.

Vasudevan, Hawkins, Parikh. (3):421-425. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann

9. Sultan I, Casanova M, Ferrari A, Rihani R, Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683-690.

Rodriguez-Galindo C. Differential features of

222 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery March 2016 Volume 142, Number 3 jamaotolaryngology.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- JSCBXCCGHXJBNCB JHNN XHDCJDocumento1 paginaJSCBXCCGHXJBNCB JHNN XHDCJNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jadwal Jaga Pagi Dokter Muda: Stase Obstetri Dan Ginekologi RS Muhammadiyah Palembang Periode 17 Juli S.D 20 Agustus 2017Documento1 paginaJadwal Jaga Pagi Dokter Muda: Stase Obstetri Dan Ginekologi RS Muhammadiyah Palembang Periode 17 Juli S.D 20 Agustus 2017NilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- XXZDocumento1 paginaXXZNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dapus RadDocumento2 pagineDapus RadNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Follow Up TanggDocumento6 pagineFollow Up TanggNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Follow Up TanggDocumento6 pagineFollow Up TanggNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dapus RadDocumento2 pagineDapus RadNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jco 2015 60 9347Documento10 pagineJco 2015 60 9347NilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis Management AndPreventionofRabiesDocumento10 pagineDiagnosis Management AndPreventionofRabiesNilaFitriOlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar PustakaDocumento2 pagineDaftar PustakaRetza Prawira PutraNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Aurum Metallicum - Picture of A Homeopathic RemedyDocumento8 pagineAurum Metallicum - Picture of A Homeopathic Remedyisadore71% (7)

- Top 10 Pharma Companies in India 2022Documento8 pagineTop 10 Pharma Companies in India 2022Royal MarathaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pahs Mbbs Information BookletDocumento18 paginePahs Mbbs Information BookletKishor BajgainNessuna valutazione finora

- ArrhythmiaDocumento31 pagineArrhythmiaAbdallah Essam Al-ZireeniNessuna valutazione finora

- XxssDocumento13 pagineXxssfkhunc07Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cir 0000000000000899Documento25 pagineCir 0000000000000899hanifa ambNessuna valutazione finora

- CPR and Aed: Quiz #2 ResultsDocumento2 pagineCPR and Aed: Quiz #2 ResultsNathan WhiteNessuna valutazione finora

- Try Out Paket BDocumento13 pagineTry Out Paket BDian Purnama Dp'TmNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Casts and Their IndicationsDocumento3 pagineTypes of Casts and Their IndicationsPhylum ChordataNessuna valutazione finora

- Cure - Family Health MatterzDocumento14 pagineCure - Family Health MatterzGeorge AniborNessuna valutazione finora

- A Case-Based Guide To Clinical Endocrinology (October 23, 2015) - (1493920588) - (Springer)Documento434 pagineA Case-Based Guide To Clinical Endocrinology (October 23, 2015) - (1493920588) - (Springer)AbdulraHman KhalEd100% (2)

- Atlas de Acupuntura (Ingles)Documento16 pagineAtlas de Acupuntura (Ingles)Medicina Tradicional China - Grupo LeNessuna valutazione finora

- Framingham Risk Score SaDocumento8 pagineFramingham Risk Score Saapi-301624030Nessuna valutazione finora

- IMSS Nursing Knowledge ExamDocumento11 pagineIMSS Nursing Knowledge ExamScribdTranslationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Smell & TasteDocumento4 pagineSmell & Tasteminji_DNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample 20715Documento16 pagineSample 20715Sachin KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Maximum Marks: 100Documento35 pagineMaximum Marks: 100Yu HoyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Mink Dissection InstructionsDocumento15 pagineMink Dissection InstructionsMark PenticuffNessuna valutazione finora

- Boys Centile ChartDocumento1 paginaBoys Centile ChartElma AprilliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Minimizing Social Desirability Bias in Measuring Sensitive Topics: The Use of Forgiving Language in Item DevelopmentDocumento14 pagineMinimizing Social Desirability Bias in Measuring Sensitive Topics: The Use of Forgiving Language in Item DevelopmentKillariyPortugalNessuna valutazione finora

- 12-Channel ECG SpecsDocumento5 pagine12-Channel ECG SpecsNai PaniaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Study The Herbalism of Thyme LeavesDocumento7 pagineStudy The Herbalism of Thyme Leavespronto4meNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief History of Evidence-Based Medicine in Four PeriodsDocumento31 pagineA Brief History of Evidence-Based Medicine in Four PeriodsSaad MotawéaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dressing and BandagingDocumento5 pagineDressing and BandagingMaricar Gallamora Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Young FrankensteinDocumento109 pagineYoung FrankensteinColleen Hawks-Pierce83% (6)

- How to prepare your Asil for fightingDocumento16 pagineHow to prepare your Asil for fightingcinna01Nessuna valutazione finora

- Zingiber Officinale MonographDocumento5 pagineZingiber Officinale Monographc_j_bhattNessuna valutazione finora

- NCP OrthoDocumento2 pagineNCP OrthoJeyser T. GamutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Isolating Staphylococcus SPDocumento4 pagineIsolating Staphylococcus SPHani HairullaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ducharme Et Al, 1996Documento20 pagineDucharme Et Al, 1996GokushimakNessuna valutazione finora