Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Logic Report

Caricato da

Emmagine EyanaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Logic Report

Caricato da

Emmagine EyanaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

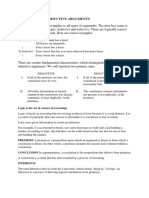

Unit 3: Analogical Argument

Using Analogies

Analogies are comparisons of one item with or two others. Analogies are used

in three different ways.

1. Analogies are used in descriptions: "Breakfast without orange juice is like a

day without sunshine."

2. In explanations: "Electrons in an atom are like planets in a solar system,

and the nucleus is like the sun the planets orbit."

3. In arguments: "My last car was a Honda. It gave me good gas mileage. I

just bought a new Honda. It will probably give me good gas mileage, too."

We will be studying the use of analogies in arguments. Unlike deductively

valid arguments, the premises of an analogical argument do not guarantee the

truth of the conclusion. They only make it more likely.

Analyzing Analogical Arguments

Like all arguments, an analogical argument offers a reason to accept some

conclusion. An analogical argument involves a comparison between two or

more persons, objects, situations, etc. An analogical argument has a form

something like the following.

a, b, c and x all have the attributes P, Q, and R. a, b, and c also have the

attribute S. So x probably has the attribute S as well.

The conclusion of this argument is, of course, that x probably has the attribute

S. We call x the target subject or the target entity and we call S the target

attribute in the argument. Here x is being compared with a, b, and c. We call

the collection a, b, and c the comparison set in the argument. The premise of

the argument is that the target subject and everything in the comparison set

share the attributes P, Q, and R. We call P, Q, and R the comparison

attributes in the argument. So we could rephrase the form of an analogical

argument like this.

The target subject shares the comparison attributes with the members of

the comparison set. But the members of the comparison set also have

the target attribute. So since the target subject is like the members of

the comparison set in these other ways, the target subjectprobably has

the target attribute as well.

The first step in evaluating an analogical argument is to determine the target

subject, the target attributes, the comparison set, and the comparison

attributes for the argument. It is usually easiest to do this if we first determine

the conclusion of the argument. The target subject of the argument is the

logical subject of the conclusion, which is usually also the grammatical

subject. The target attribute is usually given in the grammatical predicate of

the conclusion. The comparison set then contains the things that the target

subject is being compared with in the argument. And the comparison

attributes are those attributes named in the premise of the argument. The

premise assumes that we already agree that the target subject and the

members of the comparison set all have the comparison attributes.

Here's a concrete example of an analogical argument.

John Grisham's novels The Firm, The Pelican Brief, and A Time to Kill were all

made into block-buster movies. They will probably make a block-buster

movies out of his latest novel, The Testament.

The conclusion of this argument is that The Testament will become a block-

buster movie. The logical subject of the conclusion, and the target subject of

the argument, is The Testament. (Note that in this case the target subject

is not the grammatical subject.) The target attribute of the argument, is to be

a block-buster movie. In the argument, The Testament is compared with The

Firm, The Pelican Brief, and A Time to Kill. These three books comprise

the comparison set of the argument. And the premise is that all four of these

books, both the books in the comparison set and The Testament, are novels

by John Grisham. So being a novel by John Grisham is the comparison

attribute.

Evaluating Analogical Arguments

Here are some criteria we can use in evaluating the relative strength of

analogical arguments.

1. The larger the comparison set, the stronger the argument. The

more things we can name that are like the target subject that also have

the target attribute, the more convincing our argument will be. For

example, if we can name several other John Grisham novels that

became block-buster movies, the more probable it will be that his latest

novel will also become a block-buster movie. If we change our premise

to "John Grisham's novels The Firm, The Pelican Brief, A Time to

Kill, The Client, The Chamber, and Rainmaker were all made into

block-buster movies.", this strengthens the argument.

2. The more comparison attributes, the stronger the argument. The

more ways we know the target subject is like the members of the

comparison set, the more probable it will be that it is also like the

members of the comparison set in having the target attribute. If we

change our premise to "John Grisham's novels The Firm, The Pelican

Brief, A Time to Kill, The Client, The Chamber, and Rainmaker were

all made into block-buster movies", this strengthens the argument.

3. The more differences there are between the members of the

comparison set, the stronger the argument. Suppose the members

of the comparison set are quite different except that they all have the

comparison attributes. Then any ways the target subject may be

different from the members of the comparison set are less likely to be

important in determining whether the target subject will share the target

attribute with the members of the comparison set. If we change our

premise to "John Grisham's novels The Firm, The Pelican Brief, and A

Time to Kill were all made into block-buster movies. The first was

about organized crime, the second was about a conspiracy within

the government, and the third was about a poor southern African-

American who killed the man who raped his daughter.", this

strengthens the argument. The Testament will not be exactly like

Grisham's other novels that were made into block-buster movies. The

more variety there is in the stories in those other novels, the less

important it will be for our conclusion that the story in the latest novel is

different from those in the earlier books.

4. The stronger the target attribute, the weaker the argument. A strong

target attribute means that the conclusion is making a strong claim. The

stronger claim we make in our conclusion in any argument, the stronger

evidence we need to support our claim. So if the premises are the

same, then they support a weaker conclusion better than a stronger

one. In our example, the claim that The Testament will become a block-

buster movie is a pretty strong claim. We could weaken it if we just

claimed that The Testament will become a movie. By weakening the

target attribute, and thus the conclusion, we would produce a stronger

argument.

5. Disanalogies weaken an analogical argument. A disanalogy is a way

that the target subject is different from the members of the comparison

set. Disanalogies are most damaging when the difference is one that is

particularly relevant to the comparison attribute. For example, suppose

that someone were to point out that The Firm, The Pelican Brief, and A

Time to Kill were all best-sellers, but that The Testament was not selling

well. How well a book sells is certainly relevant to the decision whether

to make a movie of it. So this would be an important disanalogy

between the Grisham novels in the comparison set and The Testament.

Looking for disanalogies is an important part of evaluating an analogical

argument. Of course, no two things are exactly alike and it will always

be possible to find some ways that the target subject is different from

the members of the comparison set in an analogical argument. For

example, it might turn out that there was a picture of the author on the

back of all four of these novels, and that Grisham was wearing a coat

and tie in the photo on The Firm, The Pelican Brief, and A Time to Kill,

but he was wearing a sweater in the photo on The Testament. But this is

hardly relevant to whether the book will be made into a movie and does

not weaken the argument.

6. The more relevant the comparison attributes are to the target

attribute, the stronger the argument. And of course, the less relevant

the comparison attributes are, the weaker the argument. If we change

our premise to "The novels The Firm, The Pelican Brief, A Time to

Kill were all sold at Barnes and Noble, and they were all made into

block-buster movies", this weakens the argument. A large book seller

like Barnes and Noble tries to carry the broadest selection of books

possible. That they carry a particular book is not very relevant to

whether that book is made into a movie. For example, they certainly

carry Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary and Windows 98 for Idiots,

but it's pretty unlikely either of these will be made into a movie! That all

the books mentioned in the premise of our analogical argument were

written by the same author seems much more relevant when we think

about whether another book will be made into a movie.

The Fallacy of False Analogy

We say that someone commits the fallacy of false analogy when they make

a weak analogical argument of a particular sort. The kind of analogical

argument that is usually identified as a false analogy is one where there is a

glaring disanalogy between the target subject and the members of the

comparison set. Here is an example.

It is cruel to encourage the suffering of unwanted and abandoned puppies and

kittens. That is why we spay or neuter our pets. But surely people are more

important than pets, and the suffering of an unwanted and abandoned child is

far worse than the suffering of a dog or cat. If we sterilize our pets to prevent

suffering, then we can surely do no less for the poor and homeless.

This argument is disturbing and distasteful. It is also a false analogy - an

extremely weak argument. But what makes it so weak? First, let's analyze the

argument. The target subject is poor and homeless people and the

comparison set is pets. The comparison attribute is that both poor and

homeless people and pets may produce offspring that suffer because they are

unwanted and abandoned. The target attribute is that we should sterilize to

prevent this suffering. But the problem with the argument is that there is a

glaring disanalogy between pets and people. People, whether or not they are

poor or homeless, are autonomous agents with certain rights. We do not have

the moral authority to make certain choices for them. But we have not only the

authority but the responsibility to make these same choices for our pets.

These differences are highly relevant to the question whether we can

prescribe sterilization for these two groups. Dogs and cats do not understand

the consequences of their sexual behavior; they are incapable of making

choices based on the consequences of their actions. People do and can. We

do not take away the autonomy of a dog or a cat when we make a choice for it

that it is incapable of making. We do take away the autonomy of a person if

we forcibly sterilize him or her. Thus we have phrases like, "we're comparing

apples and oranges." That means any argument based on the comparison

would be a false analogy.

Using Analogies to Criticize Arguments

One important ways analogical arguments are used is to respond to other

arguments. We often try to show that an argument is a bad argument by

showing that is resembles another argument that everyone would agree is a

bad argument. The resemblance will normally be in the form of the argument.

Let's take an example. Here's the original argument, a case of affirming the

consequent.

If Jones had robbed the liquor store, he would have run from the police. Jones

ran from the police. So he probably robbed the liquor store.

Faced with an argument like this, we might try to persuade the person who

made it that their conclusion is not supported by their premise by giving an

example of another case of affirming the consequent where the premises

seem reasonable but the conclusion is clearly absurd. Here is an example.

That doesn't follow. That's like saying, "If Jones took birth control pills, he

wouldn't be pregnant. Jones isn't pregnant. So he probably takes birth control

pills."

The response is an analogical argument. The target subject is the argument

about Jones running from the police. The comparison set consists just of the

argument about Jones and the birth control pills. The comparison attribute is

that these two arguments have the same form. The target attribute is that the

premise of the argument does not support the conclusion.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Introduction To Theology (2004)Documento297 pagineIntroduction To Theology (2004)andrew100% (2)

- The Art of ReasoningDocumento21 pagineThe Art of ReasoningJustin Paul Gallano100% (1)

- Logic in LDDocumento42 pagineLogic in LDChris ElkinsNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Logical FallaciesDocumento8 pagineCommon Logical FallaciesRedrumzNessuna valutazione finora

- VFA Self-Executing Treaty Despite US Senate RatificationDocumento2 pagineVFA Self-Executing Treaty Despite US Senate RatificationEmmagine Eyana100% (1)

- Theme in Film and TV ScreenwritingDocumento6 pagineTheme in Film and TV ScreenwritingAkshata SawantNessuna valutazione finora

- LogicDocumento94 pagineLogicAbhinav AchrejaNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Affidavit (Sample)Documento17 pagineJudicial Affidavit (Sample)Cresencio Dela Cruz Jr.100% (2)

- Judicial Affidavit (Sample)Documento17 pagineJudicial Affidavit (Sample)Cresencio Dela Cruz Jr.100% (2)

- National Economy and Patrimony - Related CasesDocumento8 pagineNational Economy and Patrimony - Related CasesEmmagine Eyana100% (1)

- The Last LeafDocumento6 pagineThe Last LeafNam KhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Sucks: What to Do to Make Your Writing Much More BetterDa EverandGrammar Sucks: What to Do to Make Your Writing Much More BetterValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (6)

- Literary Analysis HandoutDocumento3 pagineLiterary Analysis Handoutapi-266273096100% (1)

- Case Digest - Object EvidenceDocumento23 pagineCase Digest - Object EvidenceEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- IP Code overviewDocumento35 pagineIP Code overviewEmmagine Eyana100% (2)

- Common Fallacies ExplainedDocumento3 pagineCommon Fallacies ExplainedCiel Quimlat100% (1)

- First Order LogicDocumento41 pagineFirst Order LogicrvprasadcNessuna valutazione finora

- Analogical Moral ArgumentationDocumento26 pagineAnalogical Moral ArgumentationManuel Salas Torres100% (1)

- Critical Thinking TextDocumento221 pagineCritical Thinking TextMayank Agrawal100% (1)

- 12.3 Appraising Analogical ArgumentsDocumento4 pagine12.3 Appraising Analogical ArgumentsZydalgLadyz Nead50% (2)

- 12.3 Appraising Analogical ArgumentsDocumento2 pagine12.3 Appraising Analogical Argumentszeepakingshit100% (1)

- Analogical ArgumentsDocumento9 pagineAnalogical ArgumentsAmmi KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Critical and Creative Thinking 1Documento9 pagineCritical and Creative Thinking 1Aboubakr SoultanNessuna valutazione finora

- Analogical Arguments: Analogy". Here Are Some ExamplesDocumento3 pagineAnalogical Arguments: Analogy". Here Are Some ExamplesKunwer TaibaNessuna valutazione finora

- Necessary, Priori, Analytic Truth - Ferolino, CherilynDocumento3 pagineNecessary, Priori, Analytic Truth - Ferolino, CherilynCherilyn FerolinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 Moore and ParkerDocumento8 pagineChapter 2 Moore and Parkerrt1220011Nessuna valutazione finora

- SemanticsDocumento8 pagineSemanticsRosfika AyuNessuna valutazione finora

- Film Thesis StatementDocumento4 pagineFilm Thesis StatementPaySomeoneToWritePaperUK100% (1)

- Common Themes in Literature ReviewDocumento7 pagineCommon Themes in Literature Reviewafmzndvyddcoio100% (1)

- Godfather Thesis StatementDocumento8 pagineGodfather Thesis Statementnicolesavoielafayette100% (2)

- Film Critique GuidelinesDocumento3 pagineFilm Critique GuidelinesPhúc ĐoànNessuna valutazione finora

- CHP 5Documento33 pagineCHP 5wwj7rrhd7hNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 What Is An ArgumentDocumento12 pagine3 What Is An Argumentakhanyile943Nessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Problems For Fregean SemanticsDocumento6 pagine5 Problems For Fregean SemanticsmamnhNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are FallaciesDocumento9 pagineWhat Are FallaciesCharles Nickson EsmeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Logic Chapter 7 FontDocumento14 pagineLogic Chapter 7 FontRomaline RiveroNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Plot Structure for FilmsDocumento5 pagineUnderstanding Plot Structure for FilmsAkshata SawantNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomson's Normativity Refutes Theories of Goodness, Virtue, CorrectnessDocumento15 pagineThomson's Normativity Refutes Theories of Goodness, Virtue, CorrectnessPapaGrigore-DanielNessuna valutazione finora

- ENG101A Freshman English: Logic and Argumentation IDocumento74 pagineENG101A Freshman English: Logic and Argumentation ICharles MK ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Analysis MethodsDocumento14 pagineConceptual Analysis MethodsVulpe CristianNessuna valutazione finora

- Thematic roles in generative grammarDocumento8 pagineThematic roles in generative grammarjazib1200Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3-Introduction To LogicDocumento8 pagineWeek 3-Introduction To LogicYsabela LaureanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Propositions and ArgumentsDocumento24 paginePropositions and ArgumentsAman SoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Propositions: On Their Modal and Temporal PropertiesDocumento19 paginePropositions: On Their Modal and Temporal PropertiesRaleigh MillerNessuna valutazione finora

- Raymond Pascual - 2.1 Introduction To LogicDocumento5 pagineRaymond Pascual - 2.1 Introduction To LogicRaymond PascualNessuna valutazione finora

- Compare and Contrast Research Paper TemplateDocumento5 pagineCompare and Contrast Research Paper Templateyjtpbivhf100% (1)

- ArgumentsDocumento15 pagineArgumentsLoev Mei NahtNessuna valutazione finora

- Five Parameters For Story Design 3Documento29 pagineFive Parameters For Story Design 3Unnati PrakashNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief Overview of Logical TheoryDocumento6 pagineA Brief Overview of Logical TheoryHyman Jay BlancoNessuna valutazione finora

- Horror Genre Research PaperDocumento8 pagineHorror Genre Research Paperegzt87qn100% (1)

- Gone Girl Thesis StatementDocumento7 pagineGone Girl Thesis Statementafknfbdpv100% (1)

- Archetypes ReimaginedDocumento7 pagineArchetypes ReimaginedKali ErikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gentle introduction to logic and fallaciesDocumento13 pagineGentle introduction to logic and fallacieslaw tharioNessuna valutazione finora

- LogicDocumento5 pagineLogicPorsh RobrigadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Logic Chapter 3Documento11 pagineLogic Chapter 3Muhammad OwaisNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomson PDFDocumento15 pagineThomson PDFXim VergüenzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Logical FallaciesDocumento51 pagineLogical FallaciesAbdul FasiehNessuna valutazione finora

- A Finger Is Part of A Hand. A Petal Is Part of A Flower.: For ExampleDocumento8 pagineA Finger Is Part of A Hand. A Petal Is Part of A Flower.: For Examplesandy navergasNessuna valutazione finora

- Analogical Arguments Exercise BankDocumento7 pagineAnalogical Arguments Exercise BankMyel CorderoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Logic of Atomic Sentences: Valid and Sound ArgumentsDocumento26 pagineThe Logic of Atomic Sentences: Valid and Sound ArgumentsandreaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction to Critical Thinking and LogicDocumento10 pagineIntroduction to Critical Thinking and LogicJudelyn Delos SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Debatable Thesis Statement For A Good Man Is Hard To FindDocumento8 pagineDebatable Thesis Statement For A Good Man Is Hard To FindWhitney Anderson100% (2)

- Critical ThinkingDocumento3 pagineCritical ThinkingThủy TrúcNessuna valutazione finora

- Samr LogcDocumento14 pagineSamr LogcMano BilliNessuna valutazione finora

- Deductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartDocumento9 pagineDeductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartUsama SahiNessuna valutazione finora

- Arguments, Formal and Informal LogicDocumento23 pagineArguments, Formal and Informal Logicyesa040486Nessuna valutazione finora

- XAT Reasoning TermsDocumento4 pagineXAT Reasoning Termsaaryan.8912Nessuna valutazione finora

- Genre Analysis Literature ReviewDocumento8 pagineGenre Analysis Literature Reviewsemizizyvyw3100% (1)

- Horror Movie Research PaperDocumento7 pagineHorror Movie Research Paperz0pilazes0m3100% (1)

- Narrative Report For Rfot 2017Documento4 pagineNarrative Report For Rfot 2017Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rainbow LadderDocumento1 paginaRainbow LadderEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Provide Personal Greetings "Good Morning Mr. Smith, Welcome To Makati Shangrila"Documento4 pagineProvide Personal Greetings "Good Morning Mr. Smith, Welcome To Makati Shangrila"Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- ItDocumento1 paginaItEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- "The Nature's Revenge": By: Emanuelle EyanaDocumento5 pagine"The Nature's Revenge": By: Emanuelle EyanaEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Document - 1Documento2 pagineDocument - 1Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest - EvidenceDocumento18 pagineCase Digest - EvidenceEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Authorize Aunt to Claim Diploma Transcript for PNPDocumento1 paginaAuthorize Aunt to Claim Diploma Transcript for PNPEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Bobby R. Henerale held training for upcoming JournalismDocumento2 pagineDr. Bobby R. Henerale held training for upcoming JournalismEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- DocumentDocumento1 paginaDocumentEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Document - 2Documento2 pagineDocument - 2Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Air France CaseDocumento2 pagineAir France CaseEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinic Doctors Schedules MakatiDocumento1 paginaClinic Doctors Schedules MakatiEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- CasesDocumento36 pagineCasesEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- LabRev Cases 1st BatchDocumento48 pagineLabRev Cases 1st BatchEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Auth Letter 3Documento1 paginaAuth Letter 3Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- REYES V CIRDocumento2 pagineREYES V CIREmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Insurance Cases CH 4Documento31 pagineInsurance Cases CH 4Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax StructureDocumento7 pagineTax StructureEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Readings Module 2 Nat ResDocumento13 pagineReadings Module 2 Nat ResEmmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- RA 8369 Family Courts Act of 1997Documento4 pagineRA 8369 Family Courts Act of 1997Sajam MelgarNessuna valutazione finora

- LTD - 111917 (Cases For Digest)Documento61 pagineLTD - 111917 (Cases For Digest)Emmagine EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 5bb85a51002d8a146a05c53c - Fruit Rockets Multiplication Division WorksheetsDocumento80 pagine5bb85a51002d8a146a05c53c - Fruit Rockets Multiplication Division WorksheetsVhel CebuNessuna valutazione finora

- With Examples From Number Theory: (Rosen 1.5, 3.1, Sections On Methods of Proving Theorems and Fallacies)Documento34 pagineWith Examples From Number Theory: (Rosen 1.5, 3.1, Sections On Methods of Proving Theorems and Fallacies)Sia SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Deductive vs Inductive Reasoning in LawDocumento3 pagineDeductive vs Inductive Reasoning in LawRaquel ChingNessuna valutazione finora

- Successive Differentiation Part II Leibnitz TheoremDocumento9 pagineSuccessive Differentiation Part II Leibnitz TheoremIT07 hemant deshmukhNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory Curs 4 (Unexpressed Standpoints and Unexpressed Premises)Documento24 pagineFundamentals of Argumentation Theory Curs 4 (Unexpressed Standpoints and Unexpressed Premises)Laura Georgiana ŞiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Sec 1 Group 4Documento13 pagineSec 1 Group 4Anonymous 8ZquBsLJNessuna valutazione finora

- activity in logic and mathematicsDocumento28 pagineactivity in logic and mathematicsVenus Abigail Gutierrez50% (2)

- Juj 2007Documento112 pagineJuj 2007Fatimah Abdul KhalidNessuna valutazione finora

- Logic Chapter04 Predicate LogicDocumento11 pagineLogic Chapter04 Predicate LogichamzaademNessuna valutazione finora

- Beginning and Intermediate Algebra 6th Edition Lial Solutions ManualDocumento90 pagineBeginning and Intermediate Algebra 6th Edition Lial Solutions ManualJamesWolfefsgr100% (45)

- 2021-08 - AUG 2021 LSAT Study CalendarDocumento5 pagine2021-08 - AUG 2021 LSAT Study CalendarFaiza MariamNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.3 Theorems About Predicates in One Variable: (G) U (X) : X 2 I (F)Documento16 pagine3.3 Theorems About Predicates in One Variable: (G) U (X) : X 2 I (F)PERMAYCELLA BERTHA ANANTANessuna valutazione finora

- Combinatorics rules inferenceDocumento3 pagineCombinatorics rules inferenceJemuel Awid RabagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fallsem2015 16 Cp3066 Qz01ans PDNF and PCNFDocumento28 pagineFallsem2015 16 Cp3066 Qz01ans PDNF and PCNFKrishnendu SNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 1 Logic and ProofDocumento73 pagineTopic 1 Logic and ProofJocelinyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Holder Inequality in Measure TheoryDocumento3 pagineHolder Inequality in Measure TheoryPop Ovidiu100% (1)

- On A Theorem of WajsbergDocumento4 pagineOn A Theorem of WajsbergAdrianRezusNessuna valutazione finora

- Final - Logic 0 Set TheoryDocumento38 pagineFinal - Logic 0 Set TheoryClarisse TanglaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Resolution in First-Order Logic: Basic Steps For Proving A Conclusion Given Premises (All Expressed in FOL)Documento5 pagineResolution in First-Order Logic: Basic Steps For Proving A Conclusion Given Premises (All Expressed in FOL)20070645Nessuna valutazione finora

- INDUCTIVEDocumento9 pagineINDUCTIVEMichael Brian TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Inductive and Deductive Reasoning - Class PresentationDocumento39 pagineInductive and Deductive Reasoning - Class PresentationPlanetSparkNessuna valutazione finora

- Group Assignment 1 Eng 105Documento6 pagineGroup Assignment 1 Eng 105rakibul islam rakibNessuna valutazione finora

- CT Lec 3 Students Copy Jan2012Documento58 pagineCT Lec 3 Students Copy Jan2012Chia Hong ChaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Logic C 5Documento15 pagineLogic C 5leehan395Nessuna valutazione finora

- Logical FallacyDocumento31 pagineLogical Fallacyapi-264878947Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cheat Sheet Cheat Sheet: Critical Thinking (Georgia State University) Critical Thinking (Georgia State University)Documento2 pagineCheat Sheet Cheat Sheet: Critical Thinking (Georgia State University) Critical Thinking (Georgia State University)pradhan.neeladriNessuna valutazione finora

- U1 QuantifiersDocumento11 pagineU1 QuantifiersSamritha SNessuna valutazione finora