Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Management of Giant Cell Tumor GCT of Proximal Tibia in A Skeletally Immature Patient

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni3 pagineGiant Cell Tumor (GCT) is a benign

aggressive tumor of skeletally mature individuals with

incidence peaking in third decade of life. In skeletally

immature individuals giant cell tumor is extremely rare

(<2%). More common in females and epi-metaphyseal

location. Here we present a case of a four years old male

child with pain and swelling proximal tibia left side,

NCCT & MRI suggestive of giant cell tumor, was treated

with excisional biopsy, curettage and void was filled with

allograft, which was taken from mother’s iliac crest.

Sample sent for histopathology was consistent with

diagnosis of giant cell tumor. Patient started weight

bearing after 2 months postoperatively. No recurrence

has been seen after 6 months of follow up.

Titolo originale

Management of Giant Cell Tumor GCT of Proximal Tibia in a Skeletally Immature Patient

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoGiant Cell Tumor (GCT) is a benign

aggressive tumor of skeletally mature individuals with

incidence peaking in third decade of life. In skeletally

immature individuals giant cell tumor is extremely rare

(<2%). More common in females and epi-metaphyseal

location. Here we present a case of a four years old male

child with pain and swelling proximal tibia left side,

NCCT & MRI suggestive of giant cell tumor, was treated

with excisional biopsy, curettage and void was filled with

allograft, which was taken from mother’s iliac crest.

Sample sent for histopathology was consistent with

diagnosis of giant cell tumor. Patient started weight

bearing after 2 months postoperatively. No recurrence

has been seen after 6 months of follow up.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni3 pagineManagement of Giant Cell Tumor GCT of Proximal Tibia in A Skeletally Immature Patient

Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) is a benign

aggressive tumor of skeletally mature individuals with

incidence peaking in third decade of life. In skeletally

immature individuals giant cell tumor is extremely rare

(<2%). More common in females and epi-metaphyseal

location. Here we present a case of a four years old male

child with pain and swelling proximal tibia left side,

NCCT & MRI suggestive of giant cell tumor, was treated

with excisional biopsy, curettage and void was filled with

allograft, which was taken from mother’s iliac crest.

Sample sent for histopathology was consistent with

diagnosis of giant cell tumor. Patient started weight

bearing after 2 months postoperatively. No recurrence

has been seen after 6 months of follow up.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 3

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456 –2165

Management of Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) of Proximal

Tibia in a Skeletally Immature Patient: A Rare Case

Report.

Dr. Rajesh Sharma1 , Dr. R.P. Meena2

1 rd

[3 year Orthopaedic Resident, Govt. Medical College, Kota (Rajasthan)]

2

Professor & Unit Head, Department of Orthopaedics, Govt. Medical College, Kota (Rajasthan)]

Abstract:-Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) is a benign II. CASE REPORT

aggressive tumor of skeletally mature individuals with Our patient was 4 years old male child, presented with pain

incidence peaking in third decade of life. In skeletally and swelling left upper leg. His mother first noticed swelling

immature individuals giant cell tumor is extremely rare while bathing her child 6 months ago but initially ignored it.

(<2%). More common in females and epi-metaphyseal After two months it again came into attention because of

location. Here we present a case of a four years old male pain while walking. They attended Orthopaedic department,

child with pain and swelling proximal tibia left side,

NCCT & MRI suggestive of giant cell tumor, was treated New Hospital, Govt. Medical College, Kota and thoroughly

with excisional biopsy, curettage and void was filled with investigated.

allograft, which was taken from mother’s iliac crest.

Sample sent for histopathology was consistent with Routine blood investigations were within normal limit. X

diagnosis of giant cell tumor. Patient started weight ray left knee joint shows eccentric lytic metaphyseal lesion

bearing after 2 months postoperatively. No recurrence of left upper tibia with partial physeal destruction. For more

has been seen after 6 months of follow up. evaluation we advised NCCT left knee joint, interpretation

was; proximal metaphyseal end of left tibia showing 65mm

Keywords:-Giant Cell Tumor, Proximal Tibia, Excisional x 33mm expansile, lytic lesion with thinning of cortex and

Biopsy, Allograft. breach of cortex at few places suggestive of GCT [fig.1].

FNAC finding also suggestive of GCT. MRI done to see

I. INTRODUCTION local invasion, interpretation was; T1 weighted MRI shows

Cooper in1818 first described GCT of bones (1). Later intense enhancement of metaphyseal lesion of proximal tibia

Nelaton showed their local aggressiveness, and Virchow with cortical break and extension into adjacent soft tissue.

revealed their malignant potential.GCT is the bone tumor of Mother was tested for the presence of viral diseases and

skeletally mature individuals with peak incidence in third viral markers for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV were

decade of life. It represents approximately 5% of all primary done. She was found to be negative for the presence of any

bone tumours (2,3). Incidence of GCT in children and disease.

adolescent is extremely rare (<2%), as a consequence, there

is limited literature documenting the course of the disease in We performed intralesional curettage and biopsy. The void

the immature skeleton (Campbell). It is a benign but locally was filled with allograft which was taken from mother’s

aggressive tumor with <5% malignant potential. It may iliac crest. The surgery was conducted simultaneously in

metastasize most commonly to the lungs (Campbell).It has two tables, so that there was a minimum possible time gap

female predominance and most commonly involves between the graft harvestation and transplantation. Biopsy

epiphysio-metaphyseal region of long bones.[distal sample sent for histopathological examination for

femur(m/c) > proximal tibia > distal radius].Here we present confirmation of diagnosis. Interpretation was: ‘sheets of

a rare case of 4 years old male child with GCT left proximal evenly distributed multinucleated giant cells (10-60 nuclei)

tibia to evaluate the clinical efficacy of the mother’s bone in the background of benign stromal cells with mild to

graft and radiological healing of the osteolytic lesion after moderate atypia. Stromal cells infiltrating surrounding

intralesional curettage of GCT in skeletally immature adipose tissues and skeletal muscles’. All these features

individual. suggestive of GCT.

Patient was immobilized by GT POP slab for 30 days [fig.2]

and then non weight bearing mobilization was

started[fig.3].Full weight bearing was allowed after two

months [fig.4].

IJISRT18FB55 www.ijisrt.com 181

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456 –2165

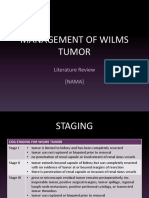

Fig. [1] Fig. [2]

Fig. [7] Fig. [8]

[Fig.(2) is Digital Skiagram Showing Anteroposterior and

Lateral View At 6 Months Follow-Up

Postoperatively;Fig.(6), fig.(7) &fig.(8) are Clinical

Photographs at 6 Months Follow-Up Showing Sitting,

Squatting And Cross-Leg Positions Respectively]

We did not observed any clinical or radiological evidence of

recurrence. Though it is too early to comment on recurrence.

III. DISCUSSION

Peak incidence of GCT is in third decade of life. It is very

Fig. [3] Fig. [4] rare in childhood (4).Our case is a male child, although most

of the literature shows female predominance (5) in GCT, but

[Fig.(1) shows preoperative NCCT of left knee joint;fig.(2),

others have found no difference between the genders [4].

fig.(3)& fig.(4) are digital skiagrams (anteroposterior and

lateral views) showing postoperative follow-ups at 30 days The lesions of GCT in adults are located in the metaphyseo-

with slab, at 30 days after removal of POP slab, and at two epiphyses of long bones. In our case lesion is at metaphyses

months respectively] of proximal tibia. Goldenberg et al [6] reported that purely

metaphyseal lesions were more common in young patients.

At present (6 months follow up) patient has pain free,

mobile knee joint without clinical evidence of any soft tissue Different surgical methods are available ranging from

complications or distal neurovascular deficit. [fig.5-8] intralesional curettage to arthrodesis of joint. But the

consensus regarding selection of ideal treatment method is

still in debate.We choose treatment modality as intralesional

curettage, biopsy and allograft which was taken from

mother’s iliac crest, as our patient is quite young (4 years)

and not suitable to obtain a sufficient amount of autograft.

Fresh allogeneic bone (mother bone graft) elicits both

acellular and humoral immune response. It helps in the

development of enhancing factors that block the detectable

immunity and probably protect the graft from rejection [7].

We didn’t use phenol or liquid nitrogen as adjuvant

treatment because of potential complications, such as

pathological fracture, wound healing problems, and

neurovascular injury (Campbell).

We didn’t use implant for internal fixation to avoid growth

plate/epiphyseal injury and implant associated

complications.

Though bone cement is a good space filler, easy to identify

recurrence and remainant tumor cells necrosis, but we avoid

to use it because use of bone cement in subchondral area

leads to cartilage damage and risk of subsequent

osteoarthritis. In long term follow up, development of

radiolucent line at bone-cement interface leads to cement

loosening and stress fracture (Takuro wada et al 2002).

Fig. [5] Fig. [6]

IJISRT18FB55 www.ijisrt.com 182

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456 –2165

After curettage recurrence rate of GCT in adult population is

14–25% [8] and in younger patients it is between 8%-20%

[9] within three years. In our case there is no evidence of

any clinical or radiological features of recurrence after six

months of follow-up, although it is too early to comment on

recurrence and patient is still in follow-up.

IV. CONCLUSION

Intralesional curettage and allograft (mother bone graft) is a

good alternative treatment modality for GCT in skeletally

immature individuals with good functional and radiological

outcome and less complications.

REFERENCES

[1]. Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin

North Am. 2006; 37(1):35–51.

[2]. Eckardt JJ, Grogan TJ. Giant cell tumor of bone. Clin

Orthop Relat Res. 1986; 204(2):45–58.

[3]. McGrath PJ. Giant-cell tumour of bone: an analysis of

fifty-two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972; 54(2): 216–

29.

[4]. M. Campanacci, A. Giunti, and R. Olmi, “Metaphyseal

and diaphyseal localization of giant cell tumors,” La

Chirurgia Degli Organi di Movimento, vol. 62, no. 1,

pp. 29–34, 1975.

[5]. K. K. Unni and C. Y. Inwards, Dahlin’s Bone Tumors:

General Aspects and Data on 10,165 Cases, Lippincott

Williams and Wilkins, 2010.

[6]. R. R. Goldenberg, C. J. Campbell, and M. Bonfiglio,

“Giant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of two hundred

and eighteen cases,”The Journal of Bone & Joint

Surgery—American Volume, vol. 52,no. 4, pp. 619–

664, 1970.

[7]. Langer F, Czitrom A, Pritzker KP, Gross AE (1975)

The immunogenicity of fresh and frozen allogeneic

bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 57(2), 216–220.

[8]. R. E. Turcotte, J. S. Wunder, M. H. Isler et al., “Giant

cell tumor of long bone: a Canadian Sarcoma Group

study,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, no.

397, pp. 248–258, 2002.

[9]. P. Picci, M. Manfrini, V. Zucchi et al., “Giant-cell

tumor of bone in skeletally immature patients,” The

Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—American Volume,

vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 486–490, 1983.

IJISRT18FB55 www.ijisrt.com 183

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Quality By Plan Approach-To Explanatory Strategy ApprovalDocumento4 pagineQuality By Plan Approach-To Explanatory Strategy ApprovalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison of Lateral Cephalograms with Photographs for Assessing Anterior Malar Prominence in Maharashtrian PopulationDocumento8 pagineComparison of Lateral Cephalograms with Photographs for Assessing Anterior Malar Prominence in Maharashtrian PopulationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Experiences of Non-PE Teachers in Teaching First Aid and Emergency Response: A Phenomenological StudyDocumento89 pagineThe Experiences of Non-PE Teachers in Teaching First Aid and Emergency Response: A Phenomenological StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Targeted Drug Delivery through the Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticle by Co-Precipitation Method and Creating a Silica Coating on itDocumento6 pagineTargeted Drug Delivery through the Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticle by Co-Precipitation Method and Creating a Silica Coating on itInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review on Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing using ThermoplasticDocumento4 pagineA Review on Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing using ThermoplasticInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gardening Business System Using CNN – With Plant Recognition FeatureDocumento4 pagineGardening Business System Using CNN – With Plant Recognition FeatureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Investigating the Impact of the Central Agricultural Research Institute's (CARI) Agricultural Extension Services on the Productivity and Livelihoods of Farmers in Bong County, Liberia, from 2013 to 2017Documento12 pagineInvestigating the Impact of the Central Agricultural Research Institute's (CARI) Agricultural Extension Services on the Productivity and Livelihoods of Farmers in Bong County, Liberia, from 2013 to 2017International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Optimizing Sound Quality and Immersion of a Proposed Cinema in Victoria Island, NigeriaDocumento4 pagineOptimizing Sound Quality and Immersion of a Proposed Cinema in Victoria Island, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Databricks- Data Intelligence Platform for Advanced Data ArchitectureDocumento5 pagineDatabricks- Data Intelligence Platform for Advanced Data ArchitectureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Administration Consultancy Administrations, a Survival Methodology for Little and Medium Undertakings (SMEs): The Thailand InvolvementDocumento4 pagineAdministration Consultancy Administrations, a Survival Methodology for Little and Medium Undertakings (SMEs): The Thailand InvolvementInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Anxiety, Stress and Depression in Overseas Medical Students and its Associated Factors: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study at Jalalabad State University, Jalalabad, KyrgyzstanDocumento7 pagineAnxiety, Stress and Depression in Overseas Medical Students and its Associated Factors: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study at Jalalabad State University, Jalalabad, KyrgyzstanInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology90% (10)

- Digital Pathways to Empowerment: Unraveling Women's Journeys in Atmanirbhar Bharat through ICT - A Qualitative ExplorationDocumento7 pagineDigital Pathways to Empowerment: Unraveling Women's Journeys in Atmanirbhar Bharat through ICT - A Qualitative ExplorationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Artificial Lift Selection Methods in Conventional and Unconventional Wells: A Summary and Review from Old Techniques to Machine Learning ApplicationsDocumento15 pagineArtificial Lift Selection Methods in Conventional and Unconventional Wells: A Summary and Review from Old Techniques to Machine Learning ApplicationsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Post-Treatment Effects of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) on the Executive and Memory Functions ofCommercial Pilots in the UAEDocumento7 paginePost-Treatment Effects of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) on the Executive and Memory Functions ofCommercial Pilots in the UAEInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Examining the Role of Work-Life Balance Programs in Reducing Burnout among Healthcare Workers: A Case Study of C.B. Dunbar Hospital and the Baptist Clinic in Gbarnga City, Bong County, LiberiaDocumento10 pagineExamining the Role of Work-Life Balance Programs in Reducing Burnout among Healthcare Workers: A Case Study of C.B. Dunbar Hospital and the Baptist Clinic in Gbarnga City, Bong County, LiberiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Harnessing Deep Learning Methods for Detecting Different Retinal Diseases: A Multi-Categorical Classification MethodologyDocumento11 pagineHarnessing Deep Learning Methods for Detecting Different Retinal Diseases: A Multi-Categorical Classification MethodologyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Development of a Local Government Service Delivery Framework in Zambia: A Case of the Lusaka City Council, Ndola City Council and Kafue Town Council Roads and Storm Drain DepartmentDocumento13 pagineDevelopment of a Local Government Service Delivery Framework in Zambia: A Case of the Lusaka City Council, Ndola City Council and Kafue Town Council Roads and Storm Drain DepartmentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Risk Factors Affecting Road Work Construction Failure in Sigi DistrictDocumento11 pagineAnalysis of Risk Factors Affecting Road Work Construction Failure in Sigi DistrictInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemical Farming, Emerging Issues of Chemical FarmingDocumento7 pagineChemical Farming, Emerging Issues of Chemical FarmingInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibacterial Herbal Mouthwash Formulation and Evaluation Against Oral DisordersDocumento10 pagineAntibacterial Herbal Mouthwash Formulation and Evaluation Against Oral DisordersInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Work-Life Balance: Women with at Least One Sick or Disabled ChildDocumento10 pagineWork-Life Balance: Women with at Least One Sick or Disabled ChildInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Study of Advanced Techniques for Inquisition, Segregation and Removal of Microplastics from Water Streams: Current Insights and Future DirectionsDocumento6 pagineStudy of Advanced Techniques for Inquisition, Segregation and Removal of Microplastics from Water Streams: Current Insights and Future DirectionsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Shaping the Future of Transportation with AutomationDocumento8 pagineShaping the Future of Transportation with AutomationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Strategic Physiognomy Elements on Organizational SuccessDocumento4 pagineThe Impact of Strategic Physiognomy Elements on Organizational SuccessInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristic of Western and Kannada Absurd DramasDocumento3 pagineCharacteristic of Western and Kannada Absurd DramasInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospective Analysis of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome: Clinical Characteristics and Patient Outcomes in a Tertiary Care Pediatric SettingDocumento7 pagineProspective Analysis of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome: Clinical Characteristics and Patient Outcomes in a Tertiary Care Pediatric SettingInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Design Of Tangentially Fired Pulverized Coal Burner Nozzle For Enhanced Erosion ResistanceDocumento8 pagineDesign Of Tangentially Fired Pulverized Coal Burner Nozzle For Enhanced Erosion ResistanceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Graduating Accountancy Students’ Digital Competencies on Industry 4.0 Career Preparedness Moderated by: Experiential LearningDocumento12 pagineGraduating Accountancy Students’ Digital Competencies on Industry 4.0 Career Preparedness Moderated by: Experiential LearningInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Crowdsourcing: An Education FrameworkDocumento6 pagineCrowdsourcing: An Education FrameworkInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Interest of Secondary School Students Towards Stem Education in Delhi RegionDocumento6 pagineInterest of Secondary School Students Towards Stem Education in Delhi RegionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Abdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveDocumento6 pagineAbdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveIulia CeveiNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Alick MwambunguDocumento68 pagineInfectious Disease Epidemiology: Alick Mwambungumwambungup100% (2)

- Delivery and Newborn Care AssessmentDocumento4 pagineDelivery and Newborn Care AssessmentNaomi RebongNessuna valutazione finora

- HNP: Herniated Nucleus PulposusDocumento29 pagineHNP: Herniated Nucleus PulposusBanni Aprilita Pratiwi100% (2)

- Ramacula Potts T11-L1 v4.5Documento10 pagineRamacula Potts T11-L1 v4.5Justitia Et PrudentiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 011 Exam Focus Dec 22Documento25 pagine011 Exam Focus Dec 22Moyooree BiswasNessuna valutazione finora

- SpondylolysisDocumento13 pagineSpondylolysisYang100% (1)

- Auditing Hospital Associated InfectionsDocumento59 pagineAuditing Hospital Associated Infectionstummalapalli venkateswara raoNessuna valutazione finora

- SC Auto SurgDocumento5 pagineSC Auto SurgBen Haim nanlonyNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Qi Imbalances and 5 Elements: A New System For Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento5 pagine4 Qi Imbalances and 5 Elements: A New System For Diagnosis and Treatmentpixey55Nessuna valutazione finora

- RCSI Course Book Chapters 22-27 Week 4Documento75 pagineRCSI Course Book Chapters 22-27 Week 4BoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiology Assignment: Complete Blood CountDocumento7 paginePhysiology Assignment: Complete Blood CountMuhammad ShahbazNessuna valutazione finora

- Management of Wilms Tumor: Literature Review (NAMA)Documento15 pagineManagement of Wilms Tumor: Literature Review (NAMA)DeaNataliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissociative Identity DisorderDocumento2 pagineDissociative Identity DisorderAnca Crețu0% (1)

- Burns and InjuryDocumento27 pagineBurns and InjuryJane Ann Alolod100% (1)

- Slide Management of AIS As An Emergency V3Documento54 pagineSlide Management of AIS As An Emergency V3maskuri82Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ergonomics Worksheet GuideDocumento3 pagineErgonomics Worksheet GuideLeony BasonNessuna valutazione finora

- RinderpestDocumento5 pagineRinderpestKinara PutriNessuna valutazione finora

- Disfuncion Erectil y Farmacos.Documento7 pagineDisfuncion Erectil y Farmacos.Danisse RoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Hypertension - EditedDocumento8 pagineCase Study Hypertension - EditedJayReneNessuna valutazione finora

- PEXIVAS The End of Plasmapheresis For ANCA-Associated Vasculitis - CJASN 2020Documento3 paginePEXIVAS The End of Plasmapheresis For ANCA-Associated Vasculitis - CJASN 2020drshhagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacological Sheet for SupermanDocumento17 paginePharmacological Sheet for SupermanIngrid NicolasNessuna valutazione finora

- Bronchial AsthmaDocumento3 pagineBronchial AsthmaSabrina Reyes0% (1)

- Treat Inflammation and Allergies with Hydrocortisone Sodium SuccinateDocumento3 pagineTreat Inflammation and Allergies with Hydrocortisone Sodium SuccinateJesrel DelotaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stages of Alzheimer's DiseaseDocumento3 pagineStages of Alzheimer's DiseaserandyNessuna valutazione finora

- antiNEOPLASTICmanPrinterFriendly PDFDocumento1 paginaantiNEOPLASTICmanPrinterFriendly PDFdarla ryanNessuna valutazione finora

- PE Recall AMC ExamDocumento9 paginePE Recall AMC ExamSherif Elbadrawy100% (1)

- CEFUROXIMEDocumento3 pagineCEFUROXIMEGwyn RosalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Rheumatoid Arthritis - 6 PDFDocumento4 pagineJurnal Rheumatoid Arthritis - 6 PDFJeanstepanisaragihNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Essay 1 Cause and Effect of Obesity EssayDocumento2 pagineSample Essay 1 Cause and Effect of Obesity EssayZi Xian LiewNessuna valutazione finora