Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Patch of Sky

Caricato da

Jerome MetierreCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Patch of Sky

Caricato da

Jerome MetierreCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Patch of Sky

Niwa Fumio

Ryokun and his friend walked along the path between the paddy fields. Ahead of them

stood the dark, luxuriant Heron’s Forest. It was about a kilometer from where the houses ended,

and stood out like an island among the fields—in time of the ripe-blossom, an emerald island

floating on a sea of yellow; in the barley season, an island in a green sea, itself a richer, more

brilliant green.

A plan to make it the center of a new park for the town had been drawn up, but nothing

had been done yet to carry it out. Even at a distance, the wood looked old and mysterious as though

it had a history of its own. It was surrounded by paddy fields. Just before reaching it, the path was

cut off by a ditch, dug centuries ago to protect a fortress in the woods. The ditch had been filled in,

but a perennial spring turned most of it into a bog, into which a man could sink up to his chest.

Ryokun loved the forest. Day after day he came back to it, as though to store up memories

of his childhood. To his childish imagination it was huge—it covered about five acres—and

reminded him of some vast, far-stretching range of mountains. Within its depths were valleys, hills,

open spaces, hundreds of giant trees hiding the sky—cryptomerias, that even Ryokun and two of

his friends together could hardly reach round. A Shinto shrine lay hidden in the dense foliage,

deserted except on festival days, when the priest would come from Tan’ami. No sound but the

chirping of birds disturbed the silence. Before them stood the stone tori of the shrine. With a shout,

Ryokun and his friend dashed into the woods making for a huge cryptomeria that grew aslant, at

an angle of nearly thirty degrees, as if it was falling over. It had been blown down by a typhoon long

ago, and had grown that way ever since. The first boy to reach the tree would climb it up; then the

game was to see who could climb higher.

Ryokun was first at the trunk. Shouting with excitement, he ran four fourteen or fifteen feet

up it and then, the impetus of his dash from the edge of the wood exhausted, stopped dead, gravity

pulling him back. This was the moment to bring his muscles consciously into play—to spin around

the instant body came to a standstill, without stopping to breathe, and race down the ground. The

least slip meant a fall or at best slithering down the trunk, one’s arms around it to avoid toppling off.

It was perfectly smooth, even the rubber sports shoes the boys always wore had been enough to

peel off the bark. A boy who was clumsy or frightened or hadn’t perfect control of his muscles would

fall off the trunk, or slip and collapse astride it, before he was six feet up.

Ryokun loved the thrill of the rush up the tree, the sudden turn, the dash to the bottom

again. His feelings during those few seconds were complex. The moment of turning, when his body

had lost its impetus, brought a stab of despair, for a split-second his head felt empty, like a

passenger in an airplane the moment it leaves the ground. Involuntarily, in that moment of panic, he would cry out. “Mother…!”

Then once more the headlong run down, carrying him thirty feet beyond the bottom of the tree.

Ryokun loved the thrill of the rush up the tree, the sudden turn. It made him feel lonely or sad or uneasy—such feeling, whatever

its immediate cause, resembling his original sense of desolation at losing his mother, so that it always made him think of her. At other

times she no longer existed for him.

Straining to beat his friend, Ryokun raced up the smooth round tree. At the end of the run, he was suddenly afraid. Till then,

there had been nothing but the thrill of the race, now, the height of the tree terrified him. If he let go his hands, nothing could stop him

from failing. Below, his companion was still shouting, egging him on. Clinging desperately to the trunk, Ryokun tried to look triumphant.

he wanted to cry, but of this, his friend knew nothing. How could he get down?

It seemed impossible now. He could not move. Gradually, his fingers were growing numb, and the bare foot he had pressed

against the underside of the trunk… Even if he managed to keep holding on for a while, his hands were losing their strength, and were

bound to start slipping soon. The voice below was still shouting its admiration… hot and red-faced, all confidence drained out of him.

Ryokun held on grimly with both hands and feet. He looked up a small patch of sky peered down through the trees.

“Mother!”

He was sorry he had come so high, and told himself he would never run up the tree again, or if he did, only so far so that he

would not have to go through this again.

Still he could not move. The shouting stopped. At last, his companion had realized apparently, that he was in difficulty. Holding

his breath, he stared up, suddenly aware of Ryokun’s terror.

“Ryokun!” The half-whispered exclamation showed his own fear. Ryokun began to slip. It was up to his hands and legs now to

save him. Little by little, a few inches at a time, the rigid body slipped. Only his head moved freely, as if with a separate life of its own,

looking to right and left, then straight down, trying to guess his height. Slowly, cautiously, he came down, controlling his own descent so

much as letting gravity take him down in short, sharp pulls on the slackening muscles of his hands and feet.

At last he was standing on the grass at the foot of the tree. His friend was relieved but did not speak for a while. Nor did Ryokun.

He was flushed and tense, too agitated even to look up at the tree he had climbed. He felt strangely uneasy too, towards his friend, as

though he had been deceived in something they had both expected. By every law of probability, he should have fallen from the tree, the

fact that he had not seemed a kind of betrayal. Yet his friend, of course, had not wanted him to fall. A lucky betrayal then: it was puzzling…

The two boys walked away quickly from the tree, leaving to silence the awkward feeling each sense in the other.

Then suddenly, one of them was running up a hill. “Ya-a-a-ah!” The other followed, shouting. In a moment, they had raced to

the top. Here and there below them, the camellias were in flower, scattering dots of fire in a carpet of deep green. Chasing each other

down the slope, the boys were soon clambering up two big camellia trees. Close-packed branches made climbing safe all the way up.

“Oh…sweet!”

“Lovely!”

“Sweeter than anything!”

Tearing flowers from the branches, they sucked the pistils noisily. The camellias, a haunt of bees and butterflies, tasted like

honey, but with a special sweetness of their own; cool, fresh, containing the very essence of a flower’s life. Ryokun chewed the white tip

of each pistil. Sucking, chewing one camellia after another, again he remembered his mother. There, perhaps, in the fugitive sweetness

of each dying flower, was the taste of a child’s loneliness, to which his mother had abandoned him.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Grade 8 East Asian MusicDocumento49 pagineGrade 8 East Asian MusicMelvin Chavez Payumo100% (1)

- Learning Activity Sheets (LAS) : TITLE: Determining Social, Moral and Economic Issues in TextsDocumento4 pagineLearning Activity Sheets (LAS) : TITLE: Determining Social, Moral and Economic Issues in TextsJhanzel Cordero67% (3)

- Lesson 3 Poem Ode To The AppleDocumento1 paginaLesson 3 Poem Ode To The AppleHarmandeep KaurNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3 Lesson 1 Korean LiteratureDocumento5 pagineModule 3 Lesson 1 Korean LiteratureJonnah Sarmiento0% (1)

- Lesson Plan in 21st CenturyDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan in 21st CenturyElean Joy Reyes-GenabiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 8 Eng 2nd Quarter Learning PlanDocumento12 pagineGrade 8 Eng 2nd Quarter Learning Plan11 and 12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vocal Music of MindoroDocumento1 paginaVocal Music of MindoroRjvm Net Ca Fe50% (4)

- Genres of Viewing Grade 7Documento30 pagineGenres of Viewing Grade 7Shiela Mae FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Visual-Verbal RelationshipsDocumento5 pagineVisual-Verbal RelationshipsJonathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Florante at Laura Summary in EnglishDocumento2 pagineFlorante at Laura Summary in EnglishConcepcion Ortega TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding African Poetry and FolkloreDocumento28 pagineUnderstanding African Poetry and FolklorekristineNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2. The Love of Magdalena Jalandoni. 21st Century LiteratureDocumento5 pagineLesson 2. The Love of Magdalena Jalandoni. 21st Century LiteratureJacob SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Poems and Songs - Man's Expression of ThoughtsDocumento32 pagine1 Poems and Songs - Man's Expression of ThoughtsDiane RadaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Parable of The Rainbow ColorsDocumento1 paginaThe Parable of The Rainbow ColorsChen Tusi GofredoNessuna valutazione finora

- ARTS 8 Module 2Documento26 pagineARTS 8 Module 2Melvin Chavez PayumoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Soul of The Great BellDocumento2 pagineThe Soul of The Great BellGian Carlo Magdaleno100% (6)

- DLL Eng8 4thQ Week 6Documento7 pagineDLL Eng8 4thQ Week 6CHRISTIAN BUYOCNessuna valutazione finora

- Luis Bernardo HonwanaDocumento2 pagineLuis Bernardo HonwanaLouise Arabelle DiegoNessuna valutazione finora

- CM Grade 8 3RD QuarterDocumento3 pagineCM Grade 8 3RD QuarterRogielyn Leyson100% (1)

- Sawatdee Hello Beautiful BangkokDocumento1 paginaSawatdee Hello Beautiful BangkokYamson MillerJrNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 - AFRICAN CHILD by Eku MC GredDocumento6 pagineLesson 2 - AFRICAN CHILD by Eku MC GredLacy Ds Fruit100% (1)

- Lesson PlanDocumento7 pagineLesson PlanNslaimoa AjhNessuna valutazione finora

- Kabihasnang MyceneanDocumento14 pagineKabihasnang MyceneanJuliet Y. MariNessuna valutazione finora

- The Origin of This WorldDocumento2 pagineThe Origin of This WorldobramaestroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramayana (Summary)Documento1 paginaRamayana (Summary)Alex SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Propaganda TechniquesDocumento40 paginePropaganda TechniquesjjNessuna valutazione finora

- Hanunuo Mangyan Writing, Basketry and WeavingDocumento5 pagineHanunuo Mangyan Writing, Basketry and WeavingMyko GorospeNessuna valutazione finora

- Table of Specification: Third Periodical Examination S.Y. 2019-2020Documento4 pagineTable of Specification: Third Periodical Examination S.Y. 2019-2020Mark Jayson BacligNessuna valutazione finora

- ENGLISH 8 - Q2 - Module-3Documento36 pagineENGLISH 8 - Q2 - Module-3Kerwin Santiago ZamoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Semi Detailed Lessonplan Luna and MarDocumento2 pagineSemi Detailed Lessonplan Luna and MarShiela Marie SantiagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 8 EnglishDocumento13 pagineGrade 8 Englishjg.mariane102Nessuna valutazione finora

- Feb 10 LP Singapore SojournDocumento2 pagineFeb 10 LP Singapore SojournAida AguilarNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Plan For English 8: Basic Education DepartmentDocumento17 pagineLearning Plan For English 8: Basic Education DepartmentTrebligCondeNessuna valutazione finora

- A Glimpse of Oriental MindoroDocumento5 pagineA Glimpse of Oriental MindoroVincent BayonaNessuna valutazione finora

- 21ST Century (2) - Jessica B. BongabongDocumento8 pagine21ST Century (2) - Jessica B. BongabongJessica Aquino BarguinNessuna valutazione finora

- English Module: "Davao Oriental Academy-The School of Refuge" Iba, San Isidro, Davao OrientalDocumento27 pagineEnglish Module: "Davao Oriental Academy-The School of Refuge" Iba, San Isidro, Davao OrientalRoen RamonalNessuna valutazione finora

- FernandezDG - Why SinigangDocumento7 pagineFernandezDG - Why SinigangHNessuna valutazione finora

- ME Eng 8 Q1 0102 - SG - African Proverbs and PoetryDocumento13 pagineME Eng 8 Q1 0102 - SG - African Proverbs and PoetryazihrNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 8 English DLLDocumento42 pagineGrade 8 English DLLaireen comboyNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 Reyes, RIVER SINGING STONEDocumento1 pagina07 Reyes, RIVER SINGING STONEddewwNessuna valutazione finora

- Pliant Like A Bamboo JAZMIN ANNE TAPICDocumento2 paginePliant Like A Bamboo JAZMIN ANNE TAPICwonder petsNessuna valutazione finora

- Speech Choir PiecesDocumento5 pagineSpeech Choir PiecesBenj OrtizNessuna valutazione finora

- Quarter 3 - Module 6 Literature: Department of Education Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento14 pagineQuarter 3 - Module 6 Literature: Department of Education Republic of The PhilippinesMikaela Eunice100% (1)

- Lesson Plan in 21st Century LiteratureDocumento4 pagineLesson Plan in 21st Century LiteratureHeyZielNessuna valutazione finora

- Moonset at Central Park Station of STDocumento2 pagineMoonset at Central Park Station of STJay MaravillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3. Context and Text's MeaningDocumento16 pagineModule 3. Context and Text's MeaningJerwin MojicoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Story of The Aged Mother by Matsuo BashoDocumento3 pagineThe Story of The Aged Mother by Matsuo BashoPearl Najera PorioNessuna valutazione finora

- The SingaDocumento2 pagineThe SingaChristian Catajay70% (115)

- ImageryDocumento3 pagineImageryCrăciun AlinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cycle of The Sun and The Moon Croup 1Documento27 pagineCycle of The Sun and The Moon Croup 1RoseLie Ma Llorca BlancaNessuna valutazione finora

- Demo Sinulog FestivalDocumento29 pagineDemo Sinulog FestivalChichan S. SoretaNessuna valutazione finora

- Makato and The Cowrie ShellDocumento1 paginaMakato and The Cowrie ShellRyuzaki Renji100% (1)

- 21st Century Lit Quarter 1 Module 1 2Documento16 pagine21st Century Lit Quarter 1 Module 1 2Mikaela Ann May CapulongNessuna valutazione finora

- The Monkey and The Turtle-ELEMENTS OF A STORYDocumento2 pagineThe Monkey and The Turtle-ELEMENTS OF A STORYNino IgnacioNessuna valutazione finora

- Venn DiagramDocumento1 paginaVenn DiagramNiño Yvanne SorillaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Soul of The Great BellDocumento2 pagineThe Soul of The Great BellreneeNessuna valutazione finora

- 1st DLL DemoDocumento6 pagine1st DLL DemoMildredNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan The Parable of Rainbow ColorDocumento10 pagineLesson Plan The Parable of Rainbow ColorVeverlyn SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

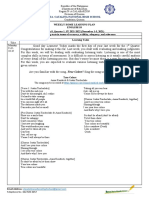

- Good Day Learners! Today Marks The First Day of Your Last Week For The 1Documento2 pagineGood Day Learners! Today Marks The First Day of Your Last Week For The 1Jerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Weekly Home Learning Plan English 10 Week 5, Quarter 1, SY 2021-2022 (October 11-15, 2021)Documento2 pagineWeekly Home Learning Plan English 10 Week 5, Quarter 1, SY 2021-2022 (October 11-15, 2021)Jerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Sta. Catalina National High SchoolDocumento3 pagineSta. Catalina National High SchoolJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Indicators Observations/Explanations: Sta. Catalina National High SchoolDocumento3 pagineIndicators Observations/Explanations: Sta. Catalina National High SchoolJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Operational and Technical DefinitionDocumento5 pagineOperational and Technical DefinitionJerome Metierre100% (4)

- English 8 Course OverviewDocumento2 pagineEnglish 8 Course OverviewJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading ComprehensionDocumento6 pagineReading ComprehensionJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- A Concept of ManagementDocumento2 pagineA Concept of ManagementJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Figures of SpeechDocumento1 paginaFigures of SpeechJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Prefixes and SuffixesDocumento1 paginaPrefixes and SuffixesJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Figures of SpeechDocumento1 paginaFigures of SpeechJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- A Concept of ManagementDocumento2 pagineA Concept of ManagementJerome MetierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Makato and The Cowrie ShellDocumento1 paginaMakato and The Cowrie ShellJerome Metierre83% (6)

- B.SC - Botany - Pteridophytes, Anatomy and Embryology - II-Year - SPS PDFDocumento160 pagineB.SC - Botany - Pteridophytes, Anatomy and Embryology - II-Year - SPS PDFAhmed KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bryophytes PDFDocumento7 pagineBryophytes PDFPoohooNessuna valutazione finora

- DaturaDocumento18 pagineDaturaSundara Veer Raju MEDNessuna valutazione finora

- PhotosynthesisDocumento6 paginePhotosynthesisAnonymous yEPScmhs2qNessuna valutazione finora

- Sedges: These Grasslike Perennials Act As Dazzling Stars or Demure Supporters in Sun and ShadeDocumento15 pagineSedges: These Grasslike Perennials Act As Dazzling Stars or Demure Supporters in Sun and ShadebryfarNessuna valutazione finora

- (Psilocybin) Psilocybin Production AdamDocumento38 pagine(Psilocybin) Psilocybin Production AdamIvaKrstićNessuna valutazione finora

- CCATMBT014Documento138 pagineCCATMBT014dharmNessuna valutazione finora

- NWFP 15 Non-Wood Forest Products From Temperate Broad-Leaved TreesDocumento133 pagineNWFP 15 Non-Wood Forest Products From Temperate Broad-Leaved TreescavrisNessuna valutazione finora

- The Buzz About Bees: Honey Bee Biology and BehaviorDocumento29 pagineThe Buzz About Bees: Honey Bee Biology and BehaviorAnnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Turmeric PlantDocumento5 pagineTurmeric PlantanjalisweNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology - Unit 02 - Allen OnlineQuestionsDocumento21 pagineBiology - Unit 02 - Allen OnlineQuestionsAnonymous sYe9kFNessuna valutazione finora

- Agriculture and Forestry McqsDocumento10 pagineAgriculture and Forestry McqsIbn E Aadam100% (1)

- Wood - PlasticsDocumento85 pagineWood - PlasticsKim Frances HerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Class 4 SST Deepika TripathyDocumento18 pagineFinal Class 4 SST Deepika TripathySURAJ GURGAONNessuna valutazione finora

- BIO Chapter 8Documento216 pagineBIO Chapter 8Jessica Platten100% (1)

- The First Land Plants: EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY: A Plant PerspectiveDocumento9 pagineThe First Land Plants: EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY: A Plant PerspectiveNindzRMapeNessuna valutazione finora

- Bio Paper FinalDocumento8 pagineBio Paper FinalNiem PhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Germination: An Excerpt From Paradise LotDocumento10 pagineGermination: An Excerpt From Paradise LotChelsea Green Publishing100% (4)

- 10 Science Imp Ch8 1Documento8 pagine10 Science Imp Ch8 1Rohan SenapathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Schuetziana 5 2014 1Documento41 pagineSchuetziana 5 2014 1Vladimir RadenkovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Orac Charts - BuenisimoDocumento92 pagineOrac Charts - BuenisimosanthigiNessuna valutazione finora

- CBSE Class 9 Biology Worksheet - TissuesDocumento17 pagineCBSE Class 9 Biology Worksheet - Tissuesaaravarora3010Nessuna valutazione finora

- All About Plants Printable BookDocumento8 pagineAll About Plants Printable BookElson TanNessuna valutazione finora

- English P1 PAT 2017 Year 4Documento14 pagineEnglish P1 PAT 2017 Year 4Mohd Fariz Abd MohsinNessuna valutazione finora

- Promalin 6P BrochureDocumento6 paginePromalin 6P Brochurepratiksha24Nessuna valutazione finora

- Anthraquinone: Iif Hanifa NurrosyidahDocumento23 pagineAnthraquinone: Iif Hanifa NurrosyidahFany LiyaraniNessuna valutazione finora

- BC 07324Documento25 pagineBC 07324Jah Bless RootsNessuna valutazione finora

- Microtomy TechniquesDocumento7 pagineMicrotomy TechniquesSabesan TNessuna valutazione finora

- Organs and Organ Systems P1Documento8 pagineOrgans and Organ Systems P1Arniel CatubigNessuna valutazione finora

- PJ - 2 - 5 - Bougainvillea Glabra.....Documento4 paginePJ - 2 - 5 - Bougainvillea Glabra.....irishjamile dulosNessuna valutazione finora