Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

375 Full

Caricato da

Renata YolandaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

375 Full

Caricato da

Renata YolandaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Article infectious diseases

Salmonella Infections

John C. Christenson, MD*

Practice Gaps

1. Because Salmonella disease causes 93.8 million illnesses and 155,000 deaths

Author Disclosure worldwide and 1 million foodborne illnesses and 350 deaths in the United States,

Dr Christenson has clinicians must learn to recognize, treat, and prevent these infections.

disclosed no financial 2. Young infants, persons with hemoglobin disorders, and individuals who are immune

relationships relevant compromised, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus and cancer, are at

to this article. This risk for severe Salmonella disease, including bacteremia, meningitis, and

commentary does not osteomyelitis.

contain discussion of

unapproved/

Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:

investigative use of

a commercial product/ 1. Describe the epidemiology of nontyphoidal salmonellosis.

device. 2. Recognize the clinical features of enteric fevers.

3. Appropriately treat the young child with Salmonella infection.

4. Understand ways to prevent Salmonella infections.

5. Use typhoid vaccines when indicated.

Introduction

Salmonella infection is a common cause of gastroenteritis and bacteremia worldwide. The

consumption of contaminated water and food and the close contact with colonized ani-

mals are frequent risk factors for acquisition. Young infants, persons with hemoglobin

disorders, and individuals who have immunocompromising conditions, such as human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer, are at risk for severe disease, such as bacter-

emia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis. Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Paratyphi are re-

sponsible for significant morbidity and mortality in developing countries. Clinicians must

learn to recognize these infections and know how to effectively treat and prevent them.

This review article provides the reader with enhanced knowledge of this diverse group of

pathogens.

Microbiology

The genus Salmonella is composed of motile gram-negative bacteria within the family En-

terobacteriaceae. They are oxidase-negative, indole-negative, and nonlactose fermenters.

The nomenclature of the genus Salmonella can be challenging. The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have been responsible for

maintaining the format for formula designation. There are 2 Salmonella species, Salmonella

enterica and Salmonella bongori, which are classified further into subspecies according to

their biochemical and genomic relatedness. Most human infections are caused by a serotype

of Salmonella enterica subsp enterica (subspecies I), which infect warm-blooded animals.

Five other subspecies (plus S bongori [subspecies V]) are known to colonize cold-blooded

animals and the environment: enterica subsp salamae (subspecies II), arizonae (subspecies

IIIa), diarizonae (subspecies IIIb), houtenae (subspecies IV), and indica (subspecies VI).

Although more than 2,600 serotypes of Salmonella have been identified, most disease

is caused by subspecies/serotypes Typhimurium and Enteritidis. Historically, serotypes

are frequently reported as species. For simplicity, in this review we use genus and

*Ryan White Center for Pediatric Infectious Disease, Indiana University School of Medicine, Riley Hospital for Children,

Indianapolis, IN.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013 375

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

subspecies/serotype (eg, Salmonella Typhi or Salmonella more likely to be bottle fed, have exposure to reptiles,

Typhimurium). Non–subspecies I are rarely reported as have ridden in a shopping cart next to meat or poultry,

human pathogens. traveled abroad, or attended a day care center with an in-

Certain serotypes frequently correlate with a disease fected infant. (4)

syndrome or food source. As examples, Salmonella chol- Most Salmonella infections are foodborne. In Mexico,

eraesuis and Salmonella dublin are both frequently asso- pork, meat, and poultry were frequently found to be

ciated with bacteremia and extraintestinal infections. contaminated with Salmonella. Consumption of con-

(1)(2) taminated orange juice led to an outbreak in a theme

park. An intentional contamination of restaurant salad

bars was responsible for a large outbreak of Salmonella

Epidemiology gastroenteritis in Oregon in 1984. Contaminated pea-

Nontyphoidal Salmonella Infections nut butter, ice cream, salami products, and mozzarella

Salmonella gastroenteritis is a serious public health prob- cheese has been responsible for multistate outbreaks

lem in the United States. An estimated 1 million food- in the United States. Outbreaks have also been associ-

borne illnesses occur each year, resulting in 350 deaths. ated with exposure to contaminated dry dog food and

(3) The world burden is estimated at 93.8 million ill- pet treats.

nesses, with 155,000 deaths each year. Salmonella Enter- Animals such as chickens, pigs, turtles, lizards, iguanas,

itidis is the most common isolated subspecies because it is hedgehogs, and amphibians have been identified as res-

responsible for 65% of these infections, followed by S Ty- ervoirs of Salmonella. Many of these colonizations have

phimurium at 12%. In the United States, exposures to resulted in human outbreaks. An outbreak of S Typhi-

chicken and eggs are most likely sources for infection. murium was associated with exposures to pet rodents.

Many risk factors are associated with infection and dis- Feeder rodents used for the feeding of reptiles and am-

semination. Achlorhydria, the use of antacids or proton phibians were found to be colonized with Salmonella,

pump inhibitors, and rapid gastric emptying favor bacterial resulting in human infections. Patients with Salmonella

survival. Conditions that impair cell-mediated lymphocyte arizonae acquired from iguanas and snakes have a predis-

function, such as HIV/AIDS, malnutrition, corticosteroid position for musculoskeletal infections. In a rare event, 2

therapy, and posttransplantation immunosuppressive ther- patients developed S Enteritidis sepsis (in one case fatal)

apy, are major risk factors. An overloaded reticuloendothe- after a platelet transfusion. The donor most likely had

lial system with iron or hemoglobin, such as in patients asymptomatic bacteremia from handling his pet boa

with sickle cell anemia, hemolytic anemia, thalassemia, constrictor.

and malaria, may increase the likelihood of severe disease. Nosocomial outbreaks are uncommon. However, in-

Infarcts in the gastrointestinal tract and bone and defective adequate infection control practices, understaffing, and

phagocytic and opsonic function also appear to contribute overcrowding may lead to environmental contamination.

to the severity of disease observed in patients who have In some developing countries, asymptomatic carriage of

sickle cell anemia. Diseases such as leukemia and lym- Salmonella can be high among children attending day

phoma also impair the reticuloendothelial system function. care centers. Outbreaks of salmonellosis in day care cen-

The morbidity and mortality associated with Salmonella ters have been reported, but these are considered rare

infections are also influenced by the serotype that causes events.

the infection. Salmonella choleraesuis is more likely to Although the incidence of salmonellosis related to

cause invasive disease. In one study, 85% of isolates were international travel appears to be decreasing in the

recovered from extraintestinal sites, especially blood. United States, many travel-acquired cases are still re-

(1) Seventy-two percent of patients were younger than ported. Salmonella stanley, a common serotype in

3 years. Pediatric patients were more likely to have diar- Southeast Asia (second most common in Thailand),

rhea than adults. Most of the children with diarrhea were has been frequently isolated in Europe. (5) In South-

also bacteremic. Mycotic aneurysms, a complication ob- east Asia, the serotype is frequently associated with

served in adults, was not detected in any of the pediatric the pork industry.

cases. Of importance, only 21% of children had leukocy- Nontyphoidal Salmonella infections remain a frequent

tosis. Occult bacteremia, where the child presents only cause of invasive disease in many regions of the world, es-

with fever, was a common presentation. pecially in sub-Saharan Africa. Children younger than

In a population-based, case-control study of salmonel- 3 years and those infected with HIV have the greatest

losis in infants younger than 1 year, infected infants were burden. Mortality remains high, especially in children with

376 Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

bacteremia and meningitis. Seasonal peaks of disease Nontyphoidal isolates are rarely invasive because most

coincide with the rainy season, which leads to fecal con- do not extend past the lamina propria or the intestinal

tamination of drinking water. In many countries, an as- lymphatic system. However, interactions with host cells

sociation between malaria and Salmonella is well known. in the intestines may lead to a release of proinflammatory

This situation often delays treatment, causing greater cytokines that result in the recruitment of neutrophils to

morbidity and mortality. Frequently, febrile persons are the area, resulting in gastroenteritis. Some genes appear

treated only for malaria without considering the likeli- to play a role in the survival of bacteria within the liver

hood of a coinfection. Clinical features, such as fevers, and spleen and promote the replication within macro-

anemia, and splenomegaly, are frequent findings in both phages. (8)

conditions. Salmonella Typhi is known to adhere to epithelial cells

over the lymphatic Peyer patches, allowing for penetra-

Enteric Fever (Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever) tion through the intestinal mucosa. Engulfment by

Enteric fever, an infection caused by S Typhi (typhoid macrophages and translocation into draining lymph

fever) or S Paratyphi A, B, or C (paratyphoid fever), is nodes results in bacteremia and subsequent dissemina-

a common cause of death and disease in many parts of tion. The organism survives within the host cells in a Salmo-

the world. Approximately 22 million cases are thought to nella-containing vacuole, assuring its ability to replicate,

occur worldwide each year, with 200,000 deaths as a result. survive, and invade and resulting in the multiplication

(6) Most infections occur in Southern and Southeast Asia. and survival of bacteria within the liver, spleen, and

Parts of Africa and Latin America are also affected but at bone marrow. After an incubation period of 7 to 14 days,

a lower frequency. In Asia, it is estimated that the inci- bacteremia occurs and symptoms emerge. Salmonella

dence approximates 100 cases per 100,000 population. Typhi can be found in the gallstones of individuals

Travelers to endemic regions are at risk. Most cases in who live in endemic regions. Its presence correlates with

the United States have been associated with international fecal shedding, and these people are known to infect

travel. Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at the others.

highest risk of infection.

In countries such as India, children and adolescents in

the 5- to 19-year age group are affected most. On rare Clinical Aspects

occasions, neonatal infections have been reported. These Nontyphoidal Salmonella Infections

infections are frequently acquired from the mother. In Gastroenteritis is the most frequent presentation. Most

South and Southeast Asia, S Typhi is the most common affected children are younger than 1 year. The usual in-

cause of community-acquired bacteremia. cubation period for Salmonella gastroenteritis is 6 to 12

Between 1960 and 1999, 60 outbreaks of typhoid hours. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are common

fever had been reported in the United States. (7) symptoms. Diarrhea is usually nonbloody. Myalgias, ar-

Ninety percent were domestically acquired. Recently, thralgias, and headaches are also reported. Although ob-

cases were found to be related to the consumption of served in children with Salmonella gastroenteritis, fever,

a fruit shake made from frozen mamey fruit from chills, and abdominal pain are more commonly observed

Guatemala. (7) In recent years, an outbreak of S Para- with shigellosis. The presence of rectal tenesmus accom-

typhi B was found to be related to exposure to pet panied by stools with mucus and/or blood is more dis-

turtles. tinctive of Shigella infections. Symptoms are generally

The major factor responsible for the magnitude of this self-limited. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are infre-

problem is poor sanitary infrastructure, resulting in substan- quently noted.

dard drinking water and contaminated food. Person-to- Bacteremia is commonly observed in infants with gas-

person transmission from chronic asymptomatic carriage troenteritis. Most children require hospitalization. Persis-

also contributes to the infection of susceptible individuals tent bacteremia can be detected in approximately 40% of

(eg, typhoid Mary). patients. Salmonella Enteritidis was a frequently isolated

pathogen in bacteremic patients. In children, bacteremia

is rarely fatal. In contrast, one-third of adults presenting

Pathogenesis with primary bacteremia have extraintestinal organ in-

The pathogenesis of salmonellosis is complex. Several vir- volvement and will die.

ulence genes are responsible for the severity of disease ob- Clinical features or laboratory parameters were unable

served with certain species. to detect children more likely to have persistent bacteremia.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013 377

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

Although focal infections were observed in 2.5% of pre- observed in approximately 15% of patients. Severe dis-

viously healthy children, one-third of children with un- ease resulted in more hospitalizations. Intestinal perfo-

derlying medical conditions had focal disease, consisting ration was a rare complication observed in less than 1%

of meningitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, pneumonia, of children.

or cholangitis. In parts of Africa, the fatality rate for bac- Thrombocytopenia and disseminated intravascular co-

teremia is close to 25%. Lower respiratory tract coinfec- agulation are markers of severe disease. Splenic abscess,

tions with tuberculosis and Streptococcus pneumoniae were brain abscess, and subdural empyema are rare complica-

common. tions of typhoid fever.

Meningitis and musculoskeletal infections are com- An analysis of travel-related cases in the United King-

mon complications in infants younger than 3 months. dom found that S Typhi and S Paratyphi infections were

It is estimated that 50% to 75% of Salmonella meningitis indistinguishable clinically. (10) Infections caused by S

occurs in the first year of life. Asymptomatic disease is also Paratyphi can be just as severe as those caused by S Typhi.

common in young infants. A well-appearing infant with Most patients had normal white blood cell counts (91%),

Salmonella gastroenteritis may be bacteremic. and 82% of patients had an elevated alanine aminotrans-

Malaria has been found to be a risk factor for invasive ferase level. Among travelers, more cases of enteric fever

nontyphoidal Salmonella infections in children. A reduc- were caused by S Paratyphi A than by S Typhi. Guillain-

tion in cases of salmonellosis was associated with a de- Barré syndrome has been described in association with S

crease in the number of malaria cases. Paratyphi A infection.

Compared with children with gastroenteritis Mixed infections with multiple pathogens occur in

alone, bacteremic children appear to have a longer du- endemic tropical countries. Treatment against enteric

ration of symptoms, a less severe clinical appearance, fever should be considered for children with unremit-

and fewer signs of dehydration. This gradual presen- ting fevers after completing adequate antimalarial

tation with less dehydration and fewer toxic effects therapy.

may lead to premature discharges from emergency

departments. Diagnosis

There are no features of Salmonella gastroenteritis that

Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever would allow its diagnosis based on clinical findings alone.

Fever, gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, vomiting, severe The routine microscopic stool examination for polymor-

diarrhea, abdominal distension, and pain), cough, rel- phonuclear cells is of limited clinical utility because a large

ative bradycardia, rose spots (pink macules frequently number of children with gastroenteritis will have a nega-

observed on the abdomen and chest), and splenomeg- tive test result (<5 polymorphonuclear cells per high-

aly are frequently regarded as features of typhoid and power field). All young infants with diarrhea, especially

paratyphoid fever. However, many patients lack these those younger than 3 months with a positive stool culture

findings, making diagnosis difficult if solely based on result, should have a blood culture performed, even if the

clinical features. In a reported foodborne epidemic, infant is well-appearing. Infants younger than 3 months

most patients had nonspecific symptoms, consisting with a positive blood culture result should undergo a lum-

of fever, headache, diarrhea, and anorexia. Hepato- bar puncture and careful examination assessing for the

megaly was seen in 7% of patients, splenomegaly in presence of musculoskeletal involvement (Table 1).

13% of patients, and rose spots in 5% of patients. Rel- (11) Any ill-appearing infant with a positive stool culture

ative bradycardia and rose spots are seldom observed in result should undergo a blood culture and lumbar punc-

children. Jaundice is frequently observed among chil- ture, be hospitalized, and be treated with parenteral

dren. Febrile convulsions have been reported in chil- antibiotics.

dren with enteric fever and may be the presenting The Widal test, a classic test that measures antibodies

symptom in some children. The incubation period against O and H antigens of S Typhi, was used for the

for enteric fevers is generally 7 to 14 days, with a range diagnosis of typhoid fever. However, its lack of sensitivity

of 3 to 60 days. and specificity has limited its utility. A false-positive test

In Pakistan, children younger than 5 years were result may lead to overtreatment and a delay in consider-

found to have more severe disease. More than 95% of ing other conditions. This outcome is especially likely in

children had fever, 20% to 41% had hepatomegaly, 5% parts of the world where typhoid fever is rare among chil-

to 20% had splenomegaly, 19% to 28% had abdominal dren and significantly less frequent than other bacterial

pain, and 8% to 35% had diarrhea. (9) Cough was pathogens.

378 Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

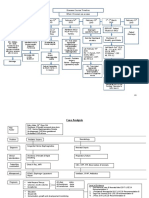

Table 1. Management of Pediatric Salmonella Gastroenteritis

Signs and Symptoms Diagnosis Management

Age <3 months

Diarrhea (dysentery-like, bloody): Obtain stool culture

Obtain blood culture

Diarrhea <5 days, not dysentery-like or bloody No stool culture Hydration

No antibiotics

Febrile Stool culture positive Treat with parenteral antibiotics, 5-7 days

Blood culture negative

Stool culture positive Lumbar puncture

Blood culture positive Treat with parenteral antibiotics:

Bacteremia only: 14 days

Meningitis: 4-6 weeks

Osteomyelitis: 4-6 weeks

History of exposure to Salmonella Obtain stool culture

Obtain blood culture

Age >3 months

Diarrhea ‡5 days: Obtain stool culture

Afebrile Stool culture positive Observation

No antibiotics

Febrile, but non–toxic-appearing Stool culture positive Blood culture

Observe off antibiotics

Toxic, ill-appearing, or Stool culture positive Blood culture

immunocompromised host Lumbar puncture

Treat with parenteral antibiotics

Stool culture positive Lumbar puncture

Blood culture positive Treat with parenteral antibiotics:

Bacteremia only: 14 days

Meningitis: 4-6 weeks

Osteomyelitis: 4-6 weeks

Adapted from: St. Geme J, Hodes H, Marcy SM, et al. Consensus: Management of Salmonella infection in the first year of life. Pediatric Infectious Disease

Journal. 1988; 7(9):615–621. Copyright 1988 (c) by Wolters Kluwer Health/Williams & Wilkens.

In patients with typhoid fever, blood culture results Treatment

are frequently positive, but stool cultures are less so. Al- Previously healthy children and adults with uncompli-

though liver enzyme levels are frequently elevated, leu- cated gastroenteritis do not require antimicrobial

kocytosis is not always observed. Leukopenia and therapy because the disease is self-limited. Infants

anemia are frequently associated with enteric fevers. A younger than 3 months with Salmonella gastroen-

normal white blood cell count does not rule out inva- teritis should be treated because they have a high

sive disease. Many suggest that bone marrow cultures incidence of extraintestinal complications, such as bac-

have a higher sensitivity. Obtaining this type of speci- teremia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis (Table 1). Antimi-

men is much more invasive and impractical in many cir- crobial therapy may prolong the carrier state. Therapy

cumstances. Approximately 20% of patients may have should be considered for those individuals with high-risk

pneumonia as documented by abnormal radiography medical conditions, such as HIV, sickle cell anemia, and

results. cancer.

Although pathogen-specific serologic and polymerase Antimicrobial treatment must take into account

chain reaction assays are the preferred methods for diag- the local epidemiology and therapeutic practice in

nosing enteric fever, diagnosis is still made using clinical the country where the infection was acquired. Chlor-

criteria in most lower-income countries. Unfortunately, amphenicol, amoxicillin, and the combination of

early features of enteric fever mimic other conditions, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are no longer rec-

such as pneumonia, malaria, sepsis, dengue, acute hepa- ommended as first-line agents for the treatment of en-

titis, and rickettsial infections. teric fevers. The high frequency of treatment failures,

Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013 379

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

resistance, and relapse rates has diminished their use- Prevention

fulness. Antimicrobial resistance observed in many Improving the quality of drinking water and food will

countries has influenced the choice of agent for treat- lead to a decrease in Salmonella cases, as will decreasing

ing typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Ceftriaxone re- exposure to high-risk animals (Table 2).

mains the recommended agent in the most severe Routine vaccination of school-age children can be an

cases in which parenteral therapy is indicated. Cefo- important component of a typhoid fever control pro-

taxime is an acceptable alternative. Although fluo- gram in an endemic region. (17) Vaccinating children

roquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, are generally younger than 2 years living in slums in India with the

associated with high cure rates, defervescence within Vi capsular polysaccharide typhoid vaccine demon-

a week, and lower relapse and fecal carriage rates, iso- strated a 61% protective effectiveness compared with

lates from many Asian countries demonstrate resistance, a placebo. In children age 2 to 5 years, the protective

rendering them ineffective. Azithromycin appears fa- effect was 80%. Of interest, the level of protection was

vorable in the treatment of these infections. (12) Until 44% among unvaccinated members of Vi vaccinee clus-

recently, fluoroquinolone resistance was uncommon in ters. (18) Similar favorable results have been observed in

most regions of Africa. In a recent study from the other countries.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, decreased cipro-

floxacin susceptibility was detected in 15.4% of tested

isolates. (13) Proper hydration, perfusion, and fever

control still remain integral components of treating Preventing Salmonella

Table 2.

enteric fever.

More than 10 years ago, multidrug resistance was un- Infections

common in Latin America. Susceptibility to ampicillin

High-risk animals

was common, and susceptibility to ceftriaxone was almost 1. Parents and children should be counseled about the

universal. At the same time, in some Mediterranean potential risk of acquiring Salmonella when owning

countries, close to one-third of isolates were resistant an iguana, lizard, snake, or turtle.

to ampicillin. 2. Owners need to wash their hands after handling

animals, their cages, or their tanks.

In infections by S choleraesuis, resistance to cipro-

3. Individuals at high risk of severe disease, such as

floxacin was observed in 28% of pediatric cases in children age <5 years and those who are

Taiwan, whereas more than 60% of cases in adults immunocompromised, should avoid contact with

had a resistant strain. (1) Irrespective of age, resis- high-risk animals.

tance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remained 4. High-risk animals should be kept out of child-care

centers.

high.

5. High-risk animals should not be allowed to roam free

Eighty-four percent of samples of ground meats within the home. They should not be kept in kitchens

(beef, turkey, and pork) purchased at several supermar- or where food is prepared. Cages and tanks should not

kets in the Washington, DC, area were found to be con- be washed in kitchen sinks.

taminated with Salmonella isolates that were resistant to Food handling

at least one antibiotic; 53% were resistant to 3 antibiot- 6. Hand hygiene should be practiced when handling raw

ics. (14) Of greater concern, 16% of the isolates were meat. Cutting boards must be cleaned thoroughly

resistant to ceftriaxone, the drug of choice for the treat- after preparing raw meat and food items that contain

raw egg.

ment of serious infections in children. In a recent

7. People should not consume raw eggs and undercooked

study of invasive salmonellosis among Thai children, meats.

ceftriaxone resistance was detected in 17.4% of iso- 8. Mothers are encouraged to breastfeed young infants.

lates. (15) This practice has shown to reduce infections.

Patients with typhoid fever complicated by delirium, Infection control

obtundation, shock, and coma may benefit from dexa- 9. Young children with enteric fever (Salmonella Typhi

methasone therapy. This adjunctive therapy appears to and Salmonella Paratyphi) should be kept out of child

lower mortality. (16) daycare centers until they have at least 3 consecutive

negative stool culture results.

Relapse rates in children are only 2% to 4% after ther-

10. Infants and children with nontyphoidal Salmonella

apy but have been reported after most regimens. Pro- gastroenteritis can return to child daycare center

longed carrier rates occur in less than 2% of infected once diarrhea has subsided.

children.

380 Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

Vaccination against typhoid fever is recommended against paratyphoid fever B has been demonstrated.

for all travelers to developing countries in Asia, (19)(20)

Latin America, and Africa, especially for those plan- Parents and their children need to be counseled about

ning to visit friends and relatives with 2 vaccines the potential risk of acquiring Salmonella if they own

available (Table 3). Travel to India, Pakistan, a high-risk pet, such as an iguana, lizard, snake, or turtle

Mexico, and Bangladesh account for most travel- (Table 2). Owners need to wash their hands after han-

related cases in the United States. Generally, typhoid dling the animals. The Centers for Disease Control and

vaccines are 50% to 80% effective in preventing Prevention has advised that reptiles and amphibians

disease. should be kept out of households with children younger

In many highly endemic countries, S Paratyphi than 5 years. Individuals at high risk of severe disease

causes close to 50% of all cases of enteric fever. In should have no contact with these animals. Reptiles

the United States, most cases of paratyphoid fever and amphibians should be kept out of child care centers

are related to international travel. No effective licensed and households with children younger than 1 year.

vaccine against S Paratyphi is available. However, cross- All documented cases of Salmonella infection must be

protective efficacy of Ty21a oral typhoid vaccine reported to county and state health departments.

Complications and Prognosis

Vaccines Licensed for the Prevention of

Table 3. Ileal perforations in the tropics

Typhoid Fever are frequently considered to be

associated with enteric fever.

Oral typhoid Between 4% and 6% of ileal per-

vaccine Ty21a For persons age ‡6 years forations were associated with S

Live-attenuated

Typhi and S Paratyphi A. In

Series: 4 doses; 1 capsule every other day parts of Africa, 50% of all admis-

(days 0, 2, 4, and 6) sions for typhoid-related ileal

Take with cool water, 1 hour before meal

perforation were in children,

Must complete series at least 1 week before

exposure with close to two-thirds occur-

Capsules must be refrigerated ring between ages 5 and 6 years.

Capsules should not be broken and contents Underdiagnosing milder cases

mixed with food/water because this of enteric fever that resulted

inactivates the vaccine; should not be taken

in delayed or inadequate anti-

with antibiotics

Repeat 4-dose series every 5 years if exposure microbial treatment may have

continues resulted in a higher rate of per-

Contraindicated in individuals with forations.

immunocompromising conditions Fever, vomiting, and abdominal

Potential adverse effects: Nausea,

tenderness and distension are sug-

abdominal pain, cramps, vomiting,

fever, headaches, and rash gestive of ileal perforation. Postop-

Injectable Vi typhoid vaccine erative complications are common,

For persons ‡2 years

Capsular polysaccharide such as surgical wound infection,

Single injection, 0.5 mL, intramuscular, intra-abdominal abscesses, ileus,

deltoid

and reperforation. Mortality is

Vaccine must be administered at least

2 weeks before exposure. high in children: close to 40% in

Thimerosal-free children younger than 5 years

Booster: Every 2 years if exposure and 20% in children older than 5

continues years. (21)

Potential adverse effects: Injection

Rhabdomyolysis with acute renal

site pain, erythema, and induration;

occasional fever and flulike symptoms. failure has been reported as a com-

plication of typhoid fever.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013 381

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

10. Patel TA, Armstrong M, Morris-Jones SD, Wright SG,

Summary Doherty T. Imported enteric fever: case series from the hospital

for tropical diseases, London, United Kingdom. Am J Trop Med

Hyg. 2010;82(6):1121–1126

• On the basis of strong research evidence, exposures to 11. Geme JW III, Hodes HL, Marcy SM, et al. Consensus:

contaminated food, water, and colonized animals are management of Salmonella infection in the first year of life. Pediatr

major risk factors for Salmonella infections. (3)(4)(7)(14) Infect Dis J. 1988;7(9):615–621

• On the basis of research evidence and consensus, 12. Chinh NT, Parry CM, Ly NT, et al. A randomized controlled

infants younger than 3 months with Salmonella comparison of azithromycin and ofloxacin for treatment of multidrug-

gastroenteritis are at an increased risk of resistant or nalidixic acid-resistant enteric fever. Antimicrob Agents

extraintestinal complications, such as bacteremia, Chemother. 2000;44(7):1855–1859

meningitis, and osteomyelitis, and must be treated 13. Lunguya O, Lejon V, Phoba MF, et al. Salmonella Typhi in

regardless of severity of illness. (4)(11) the Democratic Republic of the Congo: fluoroquinolone de-

• On the basis of strong research and epidemiologic creased susceptibility on the rise. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(11):

evidence, antimicrobial resistance is a serious problem e1921

in the treatment of typhoid fever. (12)(13)(14) 14. White DG, Zhao S, Sudler R, et al. The isolation of antibiotic-

• On the basis of strong research evidence, vaccines can resistant salmonella from retail ground meats. N Engl J Med. 2001;

effectively prevent typhoid fever. (17)(18)(19)(20) 345(16):1147–1154

• On the basis of published guidelines and current 15. Punpanich W, Netsawang S, Thippated C. Invasive salmonel-

standards of care, children younger than 5 years and losis in urban Thai children: a ten-year review. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

those with immunocompromising conditions, such as 2012;31(8):e105–e110

human immunodeficiency virus and cancer, should 16. Chisti MJ, Bardhan PK, Huq S, et al. High-dose intravenous

avoid contact with turtles, iguanas, and snakes. (3) dexamethasone in the management of diarrheal patients with

enteric fever and encephalopathy. Southeast Asian J Trop Med

Public Health. 2009;40(5):1065–1073

17. Bhan MK, Bahl R, Bhatnagar S. Typhoid and paratyphoid

References fever. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):749–762

1. Chiu CH, Chuang CH, Chiu S, Su LH, Lin TY. Salmonella 18. Sur D, Ochiai RL, Bhattacharya SK, et al. A cluster-randomized

enterica serotype Choleraesuis infections in pediatric patients. effectiveness trial of Vi typhoid vaccine in India. N Engl J Med. 2009;

Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1193–e1196 361(4):335–344

2. Cohen JI, Bartlett JA, Corey GR. Extra-intestinal manifestations 19. Pakkanen SH, Kantele JM, Kantele A. Cross-reactive gut-

of salmonella infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 1987;66(5):349–388 directed immune response against Salmonella enterica serovar

3. Chai SJ, White PL, Lathrop SL, et al. Salmonella enterica Paratyphi A and B in typhoid fever and after oral Ty21a typhoid

serotype Enteritidis: increasing incidence of domestically acquired vaccination. Vaccine. 2012;30(42):6047–6053

infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 5):S488–S497 20. Wahid R, Simon R, Zafar SJ, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Live oral

4. Jones TF, Ingram LA, Fullerton KE, et al. A case-control study typhoid vaccine Ty21a induces cross-reactive humoral immune

of the epidemiology of sporadic Salmonella infection in infants. responses against Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi A and S.

Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2380–2387 Paratyphi B in humans. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(6):

5. Hendriksen RS, Le Hello S, Bortolaia V, et al. Characterization 825–834

of isolates of Salmonella enterica serovar Stanley, a serovar endemic 21. Ekenze SO, Ikefuna AN. Typhoid intestinal perforation under

to Asia and associated with travel. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3): 5 years of age. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2008;28(1):53–58

709–720

6. Bhutta ZA. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of Suggested Reading

typhoid fever. BMJ. 2006;333(7558):78–82 Gordon MA. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease: epidemiol-

7. Loharikar A, Newton A, Rowley P, et al. Typhoid fever outbreak ogy, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24

associated with frozen mamey pulp imported from Guatemala to the (5):484–489

western United States, 2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):61–66 Tsai MH, Huang YC, Chiu CH, et al. Nontyphoidal Salmonella

8. Lahiri A, Lahiri A, Iyer N, Das P, Chakravortty D Visiting the bacteremia in previously healthy children: analysis of 199

cell biology of Salmonella infection. Microbes Infect. 2010;12(11): episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(10):909–913

809-818. Whitaker JA, Franco-Paredes C, del Rio C, Edupuganti S. Re-

9. Siddiqui FJ, Rabbani F, Hasan R, Nizami SQ, Bhutta ZA. thinking typhoid fever vaccines: implications for travelers and

Typhoid fever in children: some epidemiological considerations people living in highly endemic areas. J Travel Med. 2009;16

from Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(3):215–222 (1):46–52

Parent Resources From the AAP at HealthyChildren.org

The reader is likely to find material relevant to this article to share with parents by visiting these links:

• English: http://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/infections/Pages/Salmonella-Infections.aspx

• Spanish: http://www.healthychildren.org/spanish/health-issues/conditions/infections/paginas/salmonella-infections.aspx

382 Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

infectious diseases salmonella

PIR Quiz

This quiz is available online at http://www.pedsinreview.aappublications.org. NOTE: Learners can take Pediatrics in Review quizzes and claim credit

online only. No paper answer form will be printed in the journal.

New Minimum Performance Level Requirements

Per the 2010 revision of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician’s Recognition Award (PRA) and credit system, a minimum performance

level must be established on enduring material and journal-based CME activities that are certified for AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM. In order to

successfully complete 2013 Pediatrics in Review articles for AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM, learners must demonstrate a minimum performance level

of 60% or higher on this assessment, which measures achievement of the educational purpose and/or objectives of this activity.

In Pediatrics in Review, AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM may be claimed only if 60% or more of the questions are answered correctly. If you score less

than 60% on the assessment, you will be given additional opportunities to answer questions until an overall 60% or greater score is achieved.

1. A 6–year–old girl who presents with fever and diarrhea after a trip to India is suspected of having typhoid

fever. Which of the following findings is most frequently noted with this diagnosis?

A. Normal hemoglobin level.

B. Normal liver enzyme level.

C. Normal white blood cell count.

D. Positive blood culture result.

E. Positive stool culture result.

2. A previously healthy 9–month–old with vomiting and nonbloody diarrhea has a stool culture result positive for

Salmonella. Which of the following is appropriate treatment of this infant?

A. Azithromycin.

B. Ceftriaxone.

C. Chloramphenicol.

D. No antibiotics.

E. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

3. A 7–month–old girl is traveling with her parents to Pakistan. Which of the following preventive measures is

most appropriate for this child?

A. Avoid fresh fruits and vegetables.

B. Bathe only in fresh water ponds.

C. Injectable Vi typhoid vaccine.

D. Oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a.

E. Prophylaxis with azithromycin.

4. A 6–month–old female has a stool culture result positive for Salmonella. Her parents inquire as to what they

could do to prevent this from happening again. Which of the following features is an established risk factor for

this infection?

A. Breastfeeding.

B. Nanny at home.

C. Oatmeal cereal.

D. Pet turtle at home.

E. Travel to New Mexico.

5. Mixed infections with multiple pathogens occur in endemic tropical countries. Which of the following

disorders in children treated for enteric fever who present with unremitting fevers is therapy most appropriate?

A. Dengue.

B. Malaria.

C. Rickettsia.

D. Shigella.

E. Tuberculosis.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.34 No.9 September 2013 383

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

Salmonella Infections

John C. Christenson

Pediatrics in Review 2013;34;375

DOI: 10.1542/pir.34-9-375

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/34/9/375

References This article cites 24 articles, 7 of which you can access for free at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/34/9/375#BIBL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Journal CME

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/journal

_cme

Infectious Disease

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/infecti

ous_diseases_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions

.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xht

ml

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

Salmonella Infections

John C. Christenson

Pediatrics in Review 2013;34;375

DOI: 10.1542/pir.34-9-375

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/34/9/375

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2013 by the American Academy of

Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on February 3, 2018

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Viral Vistas: Insights into Infectious Diseases: The Invisible War: Decoding the Game of Hide and Seek with PathogensDa EverandViral Vistas: Insights into Infectious Diseases: The Invisible War: Decoding the Game of Hide and Seek with PathogensNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatrics in Review 2013 SalmonelosisDocumento11 paginePediatrics in Review 2013 SalmonelosisCarlos Elio Polo VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- 911 Pigeon Disease & Treatment Protocols!Da Everand911 Pigeon Disease & Treatment Protocols!Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Rudolph PediatricDocumento9 pagineRudolph PediatricMuhammad RezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leishmaniasis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDa EverandLeishmaniasis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Genome: Campylobacter (Meaning 'Twisted Bacteria') Is A Genus of Bacteria That Are Gram-Negative, Spiral, andDocumento7 pagineGenome: Campylobacter (Meaning 'Twisted Bacteria') Is A Genus of Bacteria That Are Gram-Negative, Spiral, andArsh McBarsh MalhotraNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella Infection GuideDocumento9 pagineSalmonella Infection GuideBijay Kumar MahatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid DiseaseDocumento28 pagineTyphoid DiseaseSaba Parvin Haque100% (1)

- Typhoid Fever - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento13 pagineTyphoid Fever - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfhasnah shintaNessuna valutazione finora

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocumento13 pagineNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptJM TovarNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella in the Caribbean: A Case StudyDocumento21 pagineSalmonella in the Caribbean: A Case StudyGuia PurificacionNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmon Ellos IsDocumento5 pagineSalmon Ellos IsIsak ShatikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonellosisincluding Entericfever: Farah Naz Qamar,, Wajid Hussain,, Sonia QureshiDocumento13 pagineSalmonellosisincluding Entericfever: Farah Naz Qamar,, Wajid Hussain,, Sonia QureshiAnak MuadzNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 For Shell 541554Documento14 pagine07 For Shell 541554frankyNessuna valutazione finora

- SalmonellaDocumento14 pagineSalmonellaTochukwu IbekweNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella, The Host and Disease: A Brief ReviewDocumento8 pagineSalmonella, The Host and Disease: A Brief ReviewPedro Albán MNessuna valutazione finora

- Advances in Pediatrics: Salmonella Infections in ChildhoodDocumento30 pagineAdvances in Pediatrics: Salmonella Infections in ChildhoodandualemNessuna valutazione finora

- Infection Salmonella Ptversion PDFDocumento3 pagineInfection Salmonella Ptversion PDFPankajNessuna valutazione finora

- Infection SalmonellaDocumento3 pagineInfection SalmonellaMaria GanganNessuna valutazione finora

- 146 - Salmonella SpeciesDocumento8 pagine146 - Salmonella SpeciesEmilio Emmanué Escobar CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review On: Salmonellosis and Its Economic and Public Health SignificanceDocumento13 pagineA Review On: Salmonellosis and Its Economic and Public Health Significanceamanmalako50Nessuna valutazione finora

- FOOD INFECTIONDocumento20 pagineFOOD INFECTIONtesnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia 2015 REVDocumento26 pagineSalmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia 2015 REVSebastián NovoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella Spp. Isolated From Poultry: A GlobalDocumento15 pagineAntibiotic Resistance in Salmonella Spp. Isolated From Poultry: A GlobalKatia RamónNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious DiseaseDocumento200 pagineInfectious DiseaseSyed Faayez KaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Salmonella Infection: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & PreventionDocumento2 pagineGlobal Salmonella Infection: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & PreventionSakshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella Taxonomy and DiseaseDocumento55 pagineSalmonella Taxonomy and DiseaseAnanaya JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonellosis 1Documento15 pagineSalmonellosis 1BforbatNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella Rapid Test: Certest BiotecDocumento16 pagineSalmonella Rapid Test: Certest BiotecOlesyaGololobovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Salmonella Enterica Isolates From Chickens in SomeDocumento11 pagineAntimicrobial Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Salmonella Enterica Isolates From Chickens in SomeMonyet...Nessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid FeverDocumento13 pagineTyphoid FeverPutri Nilam SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathogenicity of SalmonellaDocumento22 paginePathogenicity of SalmonellaTemidayoNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonellosis : NB: Version Adopted by The World Assembly of Delegates of The OIE in May 2010Documento19 pagineSalmonellosis : NB: Version Adopted by The World Assembly of Delegates of The OIE in May 2010frankyNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation SalmonellaDocumento7 pagineDissertation SalmonellaWriteMyPaperCoCanada100% (1)

- Salmonella TyphosaDocumento13 pagineSalmonella TyphosaJimson Marc DuranNessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid Fever - An Overview Good Hygiene Is The Key To Prevent Typhoid FeverDocumento8 pagineTyphoid Fever - An Overview Good Hygiene Is The Key To Prevent Typhoid FeverSyarifahNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiology - Presentation On Salmonella Outbreak Case Study.Documento15 pagineEpidemiology - Presentation On Salmonella Outbreak Case Study.Yousra khurshidNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella: Spp. Infection - A Continuous Threat WorldwideDocumento9 pagineSalmonella: Spp. Infection - A Continuous Threat WorldwideNehemie SawadogoNessuna valutazione finora

- Demam Tifoid 2016Documento8 pagineDemam Tifoid 2016Mona Mentari PagiNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella Infection: Causes, Symptoms & Prevention of Salmonella BacteriaDocumento16 pagineSalmonella Infection: Causes, Symptoms & Prevention of Salmonella Bacteriaaldrin maliaNessuna valutazione finora

- PHD Thesis SalmonellaDocumento4 paginePHD Thesis Salmonellafqzaoxjef100% (2)

- Articulo 3 - SalmonellaDocumento16 pagineArticulo 3 - SalmonellaJoiver Alean FlórezNessuna valutazione finora

- Food Microbiology and Parasito - Mrs - Dorothy Bundi - 15156Documento172 pagineFood Microbiology and Parasito - Mrs - Dorothy Bundi - 15156Edward MakemboNessuna valutazione finora

- Shupe AssignmentDocumento7 pagineShupe AssignmentBright Kasapo BowaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thypoid - RPUDocumento22 pagineThypoid - RPUERONADIAULFAH SUGITONessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 11 Bacterial Food Infections: StructureDocumento15 pagineUnit 11 Bacterial Food Infections: StructureShubhendu ChattopadhyayNessuna valutazione finora

- Parasitic Diseases OMSDocumento13 pagineParasitic Diseases OMSlacmftcNessuna valutazione finora

- 408 2022 Article 528Documento8 pagine408 2022 Article 528nathanaellee92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper On SalmonellaDocumento5 pagineResearch Paper On Salmonellaafnjowzlseoabx100% (3)

- SalmonellosisDocumento40 pagineSalmonellosispurposef49Nessuna valutazione finora

- SalmonellaDocumento7 pagineSalmonellasujithasNessuna valutazione finora

- BIO2107 - Tutorial 5 Discussion PointsDocumento4 pagineBIO2107 - Tutorial 5 Discussion PointsAjay Sookraj RamgolamNessuna valutazione finora

- Pui Et Al 2011Documento9 paginePui Et Al 2011Muhammad Bilal Bin AmirNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella EntericaDocumento9 pagineSalmonella Entericaapi-532346040Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thyfoid Fever: A Diagnostic ChallengeDocumento36 pagineThyfoid Fever: A Diagnostic ChallengeYogie DjNessuna valutazione finora

- Japanese Encephalitis: A Viral Brain InfectionDocumento50 pagineJapanese Encephalitis: A Viral Brain InfectionPhilip SebastianNessuna valutazione finora

- Salmonella EssayDocumento3 pagineSalmonella EssayAlexa LeachNessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid FeverDocumento14 pagineTyphoid FeverJames Cojab SacalNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 11648 J Ijmb 20210604 12Documento15 pagine10 11648 J Ijmb 20210604 12Monyet...Nessuna valutazione finora

- Microorganism Classification GuideDocumento26 pagineMicroorganism Classification GuidehangoverNessuna valutazione finora

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Yoke Ayukarningsih, Arief DwinandaDocumento5 paginePaediatrica Indonesiana: Yoke Ayukarningsih, Arief DwinandaRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sdgs Indicator: Goal 1: Without PovertyDocumento2 pagineSdgs Indicator: Goal 1: Without PovertyRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento46 pagineCaseRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- CR PDF.2Documento2 pagineCR PDF.2Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction and Methods for Zinc Supplementation StudyDocumento13 pagineIntroduction and Methods for Zinc Supplementation StudyRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ViiiDocumento8 pagineViiiRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Patient TimelineDocumento46 paginePatient TimelineRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Submission To Publication AS 2019Documento19 pagineSubmission To Publication AS 2019Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 - Medical Writing-IntroDocumento87 pagine01 - Medical Writing-IntroRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Timeline for Acute Myeloblastic LeukemiaDocumento37 paginePatient Timeline for Acute Myeloblastic LeukemiaRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar PustakaDocumento12 pagineDaftar PustakaRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kecanduan InternetDocumento8 pagineKecanduan InternetRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Box PlotDocumento1 paginaBox PlotRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ViiiDocumento8 pagineViiiRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bagan Analisa KasusDocumento1 paginaBagan Analisa KasusRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors in Uencing Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in AdolescentsDocumento7 pagineFactors in Uencing Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in AdolescentsRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Disease Course Timeline for High-Risk ALL CaseDocumento2 pagineDisease Course Timeline for High-Risk ALL CaseRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ultrasound Cardiac Output Monitoring PDFDocumento32 pagineUltrasound Cardiac Output Monitoring PDFRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antifungal Azole Derivatives and Their Pharmacological Potential: Prospects & RetrospectsDocumento14 pagineAntifungal Azole Derivatives and Their Pharmacological Potential: Prospects & RetrospectsRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Colloid & Crystalloid For Dengue AP 2016Documento13 pagineColloid & Crystalloid For Dengue AP 2016Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Colloid & Crystalloid For Dengue AP 2016Documento13 pagineColloid & Crystalloid For Dengue AP 2016Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Orthopedics 5 1085Documento8 pagineOrthopedics 5 1085Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 255 434 1 SMDocumento10 pagine255 434 1 SMRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rekomendasi TerapiDocumento3 pagineRekomendasi TerapiRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- SDSC Eng ColourDocumento2 pagineSDSC Eng ColourmerawatidyahsepitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abdominal Complications of Typhoid Fever 1584 9341-11-1 2Documento3 pagineAbdominal Complications of Typhoid Fever 1584 9341-11-1 2Renata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rekomendasi TerapiDocumento3 pagineRekomendasi TerapiRenata YolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal 5 Demam TypoidDocumento4 pagineJurnal 5 Demam TypoidAuliana Sania HanafiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Worksheet Therapy CebmDocumento3 pagineWorksheet Therapy Cebmandynightmare97Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparative Study of The Efficacy of 5 Days and 14 Days Ceftriaxone Therapy in Typhoid Fever in ChildrenDocumento6 pagineA Comparative Study of The Efficacy of 5 Days and 14 Days Ceftriaxone Therapy in Typhoid Fever in ChildrenIOSRjournalNessuna valutazione finora

- F.A.S.T.H.U.G: I W. AryabiantaraDocumento35 pagineF.A.S.T.H.U.G: I W. Aryabiantaraarnawaiputu60Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ozone Therapy in DentistryDocumento16 pagineOzone Therapy in Dentistryshreya das100% (1)

- Measurements in Radiology Made Easy® PDFDocumento213 pagineMeasurements in Radiology Made Easy® PDFsalah subbah100% (2)

- Who Trs 999 FinalDocumento292 pagineWho Trs 999 FinalfmeketeNessuna valutazione finora

- CSOM of Middle Ear Part 2Documento55 pagineCSOM of Middle Ear Part 2Anindya NandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmDocumento1 paginaLocal Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmSydney JenningsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Windsor University Commencement Ceremony PROOFDocumento28 pagine2014 Windsor University Commencement Ceremony PROOFKeidren LewiNessuna valutazione finora

- Salivary GlandsDocumento21 pagineSalivary GlandsHassan JaleelNessuna valutazione finora

- AIDS - The Mycoplasma EXPOSE Document PDFDocumento13 pagineAIDS - The Mycoplasma EXPOSE Document PDFPierre Le GrandeNessuna valutazione finora

- MCQS FCPSDocumento3 pagineMCQS FCPSDrKhawarfarooq SundhuNessuna valutazione finora

- List of 2nd Slot Observer For Medical and Dental Theory Examination During December-2019 PDFDocumento53 pagineList of 2nd Slot Observer For Medical and Dental Theory Examination During December-2019 PDFsudhin sunnyNessuna valutazione finora

- Arichuvadi Maruthuva Malar 2nd IssueDocumento52 pagineArichuvadi Maruthuva Malar 2nd IssueVetrivel.K.BNessuna valutazione finora

- Reverse Optic Capture of The SingleDocumento10 pagineReverse Optic Capture of The SingleIfaamaninaNessuna valutazione finora

- MemoryDocumento46 pagineMemoryMaha Al AmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Rubbing Alcohol BrochureDocumento2 pagineRubbing Alcohol BrochureShabab HuqNessuna valutazione finora

- Life Calling Map Fillable FormDocumento2 pagineLife Calling Map Fillable Formapi-300853489Nessuna valutazione finora

- Resume 101: Write A Resume That Gets You NoticedDocumento16 pagineResume 101: Write A Resume That Gets You Noticedgqu3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Annamalai University Postgraduate Medical Programmes 2020-2021Documento12 pagineAnnamalai University Postgraduate Medical Programmes 2020-2021Velmurugan mNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss: A Study of 1404 PatientsDocumento8 pagineSafety of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss: A Study of 1404 PatientsLuisNessuna valutazione finora

- Dance BenefitsDocumento9 pagineDance Benefitsapi-253454922Nessuna valutazione finora

- Life 2E Pre-Intermediate Unit 1 WB PDFDocumento8 pagineLife 2E Pre-Intermediate Unit 1 WB PDFTrần Quý Dương100% (2)

- Drug Study HydrocodoneDocumento1 paginaDrug Study HydrocodoneYlrenne DyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV)Documento21 pagineGastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV)ΦΩΦΩ ΣΠΕΝΤΖΙNessuna valutazione finora

- Pamstrong - Week 1 LegsDocumento2 paginePamstrong - Week 1 LegsSondosNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 16/lecture #9 Histamine and Antihistaminics Dr. TAC Abella July 22, 2014Documento8 pagineChapter 16/lecture #9 Histamine and Antihistaminics Dr. TAC Abella July 22, 2014Rose AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- A Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen PlanusDocumento1 paginaA Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen Planus600WPMPONessuna valutazione finora

- Meningitis Pediatrics in Review Dic 2015Documento15 pagineMeningitis Pediatrics in Review Dic 2015Edwin VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- Cghs Rates BangaloreDocumento26 pagineCghs Rates Bangaloregr_viswanathNessuna valutazione finora

- Martial Arts SecretsDocumento4 pagineMartial Arts SecretsGustavoRodriguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Free Gingival Graft Procedure OverviewDocumento1 paginaFree Gingival Graft Procedure OverviewTenzin WangyalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDa EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (13)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDa EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDa EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDa EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDa EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (402)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDa EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDa EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (78)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementDa EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (40)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDa EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDa EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (169)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDa EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesDa EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (34)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDa EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (327)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDa EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNessuna valutazione finora

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDa EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDa EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (253)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDa EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDa EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (41)

- The Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityDa EverandThe Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (109)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDa EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (33)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossDa EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDa EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDa EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (8)