Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Prevalent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection Is Associated

Caricato da

Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Prevalent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection Is Associated

Caricato da

Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

MAJOR ARTICLE

Global Theme Issue: Poverty and Human Development

Prevalent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection

is Associated with Altered Vaginal Flora

and an increased Susceptibility to Multiple

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Rupert Kaul,1,3,5 Nico J. Nagelkerke,6,8 Joshua Kimani,1,6 Elizabeth Ngugi,2 Job J. Bwayo,1,a Kelly S. MacDonald,3,4

Anu Rebbaprgada,3 Karolien Fonck,1,9 Marleen Temmerman,1,9 Allan R. Ronald,6 Stephen Moses,7 and the Kibera

HIV Study Groupb

1

Departments of Medical Microbiology and 2Community Health, University of Nairobi, Kenya; 3Department of Medicine, University of Toronto,

4

Department of Microbiology, Mount Sinai Hospital, 5Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto, 6Departments of Medical

Microbiology and 7Community Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; 8Department of Community Medicine,

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab, Emirates; 9International Centre for Reproductive Health, Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium

Background. Prevalent herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection increases human immunodeficiency virus

acquisition. We hypothesized that HSV-2 infection might also predispose individuals to acquire other common

sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Methods. We studied the association between prevalent HSV-2 infection and STI incidence in a prospective,

randomized trial of periodic STI therapy among Kenyan female sex workers. Participants were screened monthly for

infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, and at least every 6 months for bacterial vaginosis

(BV) and infection with Treponema pallidum, Trichomonas vaginalis, and/or HSV-2.

Results. Increased prevalence of HSV-2 infection and increased prevalence of BV were each associated with the

other; the direction of causality could not be determined. After stratifying for sexual risk-taking, BV status, and

antibiotic use, prevalent HSV-2 infection remained associated with an increased incidence of infection with N.

gonorrhoeae (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 4.3 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.512.2]), T. vaginalis (IRR, 2.3 [95% CI,

1.3 4.2]), and syphilis (IRR, 4.7 [95% CI, 1.119.9]). BV was associated with increased rates of infection with C.

trachomatis (IRR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.13.8]) and T. vaginalis (IRR, 8.0 [95% CI, 3.219.8]).

Conclusion. Increased prevalences of HSV-2 infection and BV were associated with each other and also associ-

ated with enhanced susceptibility to an overlapping spectrum of other STIs. Demonstration of causality will require

clinical trials that suppress HSV-2 infection, BV, or both.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection is an im- recent meta-analysis of all published studies concluded

portant cofactor in the global HIV-1 (HIV) pandemic. A that HSV-2 infection increases the risk of HIV acquisi-

tion in women by just over 3-fold [1]. In Africa, over

50% of adult women are infected by HSV-2 [2], and

Received 7 February 2007; accepted 19 April 2007; electronically published 25

statistical modeling suggests that at this prevalence, al-

October 2007.

Financial support: Rockefeller Foundation (to S.M.; 2000 HE 025); the European most half of all HIV transmission may be attributable to

Commission (to M.T.; DG VIII/8, Contract No. 7-RPR-28); the Canadian Research

HSV-2 infection [3]. The increase in the risk of HIV

Chair Programme (to R.K.); Ontario HIV Treatment Network (to K.M., Career

Scientist); and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to R.K., research grant; acquisition may be due to mucosal macro-ulceration or

to S.M., Investigator Award).

a Deceased.

micro-ulceration during HSV-2 reactivation [4, 5], but

b Members of the Kibera HIV Study Group listed at end of article. may also relate to HSV-2 infectioninduced genital in-

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Rupert Kaul, Clinical Science Division, Univer-

flammation and increases in the number of HIV-

sity of Toronto, Medical Sciences Building #6356, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S

1A8 (rupert.kaul@utoronto.ca). susceptible target cells in the genital tract mucosa, with the

The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2007; 196:16927 latter seen even in the absence of HSV-2 reactivation [6].

2007 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved.

0022-1899/2007/19611-0018$15.00

We hypothesized that HSV-2 infectioninduced al-

DOI: 10.1086/522006 terations in the mucosal immune milieu might also en-

1692 JID 2007:196 (1 December) Kaul et al.

hance host susceptibility to other sexually transmitted infections rhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, Trepo-

(STIs) and to alterations in vaginal bacterial flora (ie, bacterial nema pallidum, Haemophilus ducreyi, and of BV. Urine samples

vaginosis [BV]). HSV-2 reactivation has been shown to induce a were obtained monthly for polymerase chain reaction for N.

number of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis (Amplicor PCR Diagnostics;

female genital tract [6], and nuclear factor -B (NFB) upregu- Roche Diagnostics); these assays were run in a batched fashion

lation, a common final pathway for many inflammatory stimuli, after study completion.

has been demonstrated to enhance infection by Neisseria gonor- Detailed behavioral data and blood samples for HIV-1 IgG

rhoeae in vitro [7]. In HIV-infected individuals, both coinfection ELISA and HSV-2 ELISA (Kalon Biological) were collected every

by bacterial STIs and altered vaginal flora have been associated 3 months. Full STI screening was performed at enrolment, every

with increased levels of HIV in the genital tract, which likely 6 months thereafter, and to investigate any symptomatic genital

enhances secondary sexual transmission of HIV. Furthermore, infection; screening included culture for T. vaginalis (In Pouch

in individuals who are not infected with HIV, both bacterial STIs TV culture; Biomed Diagnostics), a Gram stain of vaginal swab

and altered vaginal flora may increase susceptibility to HIV in- sample, and serological testing (rapid plasma reagin) for syphi-

fection [8]. Therefore, if HSV-2 infection were to increase sus- lis. Bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed if there was a Nugent score

ceptibility to bacterial STIs and/or alterations of vaginal flora, of 710, incident syphilis was diagnosed if there was an increase

this would imply that HSV-2 infection enhances the sexual in rapid plasma reagin titer to 1:8, and vaginal candidiasis was

transmission of HIV both directly (through mucosal macro- diagnosed if yeast was found on Gram staining [11]. If a genital

ulceration and/or micro-ulceration and alterations in the muco- ulcer was present, a swab sample of the ulcer base was taken for

sal immune milieu) and indirectly (by increasing the incidence H. ducreyi culture on an activated charcoal medium [12]. Any

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

of other genital infections that act as HIV cofactors). This would STI diagnosed was treated according to Kenyan national guide-

emphasize the need to test HSV-2 control strategies as a means to lines, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic; symptomatic BV

reduce the transmission not only of HIV, but also of other STIs. was treated, while asymptomatic BV was not. Self-reported con-

Interactions between genital infections are complex and chal- dom use was reported on a scale of 0 5, where 0 represented

lenging to study, because the precise timing of infection acqui- no condom use, and 5 represented condom use with all

sition may be difficult to elucidate, many or most genital infec- clients.

tions are asymptomatic, and some, particularly BV, tend to Statistical methods. Poisson regression was used to calcu-

relapse frequently. In addition, BV may predispose individuals late rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the comparison

to HSV-2 acquisition [9], as well as to the acquisition of other of STI incidence rates in participants with and without HSV-2

STIs [10]. This raises the possibility that underlying alterations infection. Both the receipt of monthly azithromycin therapy and

in vaginal flora may confound observed associations between the level of sexual risk-taking (ie, with increased risk defined as

HSV-2 infection and other genital infections. reduced reported condom use and increased client numbers)

To address these questions, we examined the association of were previously found to be associated with an increased inci-

prevalent HSV-2 infection with BV and with the acquisition of dence of bacterial STIs [11, 13], and so stratified adjustment was

several different STIs. This work was performed in the context of performed to control for both factors. Sexual risk-taking was

a randomized, controlled trial of periodic presumptive STI ther- grouped into 4 levels on the basis of the weekly number of un-

apy in high-risk Kenyan sex workers as a possible strategy to protected sexual contacts, based on self-reported condom use

prevent HIV acquisition [11]. and weekly client numbers: level 1 was defined as 0.5 contacts;

level 2, 0.51 contact; level 3, 12 contacts; level 4, 2 contacts.

METHODS BV has been associated with an increased incidence of bacterial

STIs [10] and HSV-2 infection [9]. However, because BV was

Study participants and procedures. HIV IgGseronegative only treated if symptoms were present and may be rapidly recur-

Kenyan female sex workers were recruited into a randomized, rent even if treated appropriately [14], we felt that when study-

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of monthly oral azithro- ing BV as a risk factor for the acquisition of other STIs, it was

mycin therapy. The primary study end point was HIV acquisi- inappropriate to compare STI rates before and after incident BV

tion, and secondary end points were the acquisition of sexually in an individual. Rather, participants were stratified either as

transmitted infections (STIs) [11]. Ethical approval for the trial ever having had BV, either at enrolment or during clinical

was obtained from institutional review boards at the Kenyatta follow-up, or as never having had BV.

National Hospital (Nairobi, Kenya) and the University of Mani- HSV-2 seroconversion that occurred between enrolment and

toba (Winnipeg, Canada). Women received 1 g of oral azithro- the first follow-up visit was potentially due to HSV-2 infection

mycin or identical placebo monthly, as directly observed ther- acquired prior to enrolment, and therefore participants who met

apy. The primary outcome was the incidence of HIV infection, this criterion were excluded from analysis of HSV-2 infection

and secondary outcomes were rates of infection with N. gonor- associations.

Herpes Simplex 2 and STI Incidence JID 2007:196 (1 December) 1693

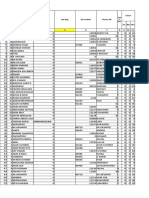

Table 1. Characteristics of Kenyan female sex Associations between genital herpes and BV. At enroll-

workers at study enrollment. ment, the prevalence of BV was higher among participants with

chronic HSV-2 infection, compared with those without (37

Variable Value

[42%] of 89 vs. 162 [53%] of 304; likelihood ratio, 3.8; P .05).

Age, years 28.8 (1852) After stratifying for sexual risk-taking and antibiotic use,

Duration of prostitution, years 5.3 (034)

chronic HSV-2 infection was also associated with an increased

Clients per week 15.7 (1100)

incidence of laboratory-confirmed BV (incidence rate ratio

Charge for sex, Kenyan shillings 133.3 (101500)

[IRR], 1.4 [95% CI, 1.11.8]; P .006). Overall, 288 (69%) of

Condom usea 2.4 (05)

Ever practice sex during menses 78 (18.8%)

416 participants had at least 1 episode of BV during follow-up,

Ever practice anal sex 62 (14.9%) and HSV-2infected participants were more likely to ever have

Ever use injection drugs 18 (4.3%) had BV, compared with those who were not HSV-2 infected (232

Infection [72.5%] of 320 vs. 56 [60.9%] of 92 ; P .04). A subgroup

Vaginal candidiasis 46/393 (11.7%) analysis including only those participants who were negative for

Bacterial vaginosis 199/393 (50.6%) BV at enrolment (N 215) found a similar association between

Neisseria gonorrhoeae 41 (9.9%) chronic HSV-2 infection and incident BV (IRR, 1.4), although

Chlamydia trachomatis 32 (7.7%) the 95% CI now included 1 (95% CI, 0.94 2.11; P .1), likely

Treponema pallidum 16 (3.8%) because of decreased participant numbers. However, the fre-

Trichomonas vaginalis 48 (11.5%)

quent recurrence of BV may confound the analysis of chronic

Herpes simplex type 2 322 (77.4%)

HSV-2 infection and BV incidence: an earlier BV episode may

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

NOTE. Data are no. (%) of participants or mean value (range). have predisposed the individual to the initial acquisition of

a

Condom use was reported on a semiquantitative scale, from

0 5 (see Methods for details).

HSV-2 , or prior HSV-2 acquisition may have predisposed the

individual to the current BV episode(s). Therefore, it might be

more accurate to report that the prevalence of HSV-2 infection

RESULTS and the prevalence of recurrent BV were associated, rather than

to analyze BV incidence.

HSV-2 infection status and baseline demographic characteristics.

Association of prevalent HSV-2 infection with other genital

Study enrollment took place from 1998 through 2002, and a total

infections. The association of prevalent HSV-2 infection with

of 466 HIV-seronegative female sex workers were enrolled [11].

the incidence of classical STIs was then analyzed, using a strati-

Serological testing for HSV-2 was performed post hoc, and en-

fied Poisson regression model (table 2). After stratifying for sex-

rollment plasma samples were available for 443 (95%) of 466

ual risk-taking, assigned study arm (i.e., azithromycin use), and

HIV-seronegative female sex workers. The seroprevalence of

BV at any time, prevalent HSV-2 infection was associated with

HSV-2 infection was 72.7% (322 of 443 female sex workers). an increased incidence of infection with N. gonorrhoeae (IRR, 4.3

HSV-2 seroconversion occurred in 24 (22.3%) of 121 HSV-2 [95% CI, 1.512.2]; P .006), T. vaginalis (IRR, 2.3 [95% CI,

uninfected participants; most HSV-2 infections (in 15 of 24 fe- 1.3 4.2]; P .004), and syphilis (IRR, 4.7 [95% CI, 1.119.9];

male sex workers) occurred between enrollment and the first P .035). As would be expected, genital ulcers were almost

follow-up visit, perhaps because of rapid postenrollment reduc- 4-fold more common in the HSV-2infected group, although

tions in sexual risk-taking [13]. Participants excluded from anal- this finding did not reach statistical significance because clinical

ysis included all of those who seroconverted to HSV-2 positive ulcers were rare (rate, 1.5 vs 0.4 ulcers per 100 person-years;

status following the baseline visit (N 24) and 3 participants adjusted IRR, 2.2 [95% CI, 0.316.3]). No association was seen

with inconsistent HSV-2 ELISA results. HSV-2 infection status between HSV-2 infection and either vaginal candidiasis (IRR,

was unchanged through clinical follow-up for 416 participants 1.1 [95% CI, 0.71.7]; P .6) or infection with C. trachomatis

(322 [77%] were HSV-2 infected, and 94 [23%] were not in- (IRR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.6 1.7]; P .99).

fected with HSV-2 ), and this population served as the basis for C. trachomatis infection has consistently been associated with

subsequent analyses of the impact of HSV-2 infection on the younger age [15], and in keeping with this the mean age of fe-

acquisition of other genital infections. male sex workers with chlamydial cervicitis at enrollment was

The mean age of participants was 28.6 years (range, 18 52 lower than that of female sex workers without (26.1 vs 28.9 years;

years) (table 1). At enrollment, women had been engaged in P .03). HSV-2 infection is a persistent infection, and its prev-

commercial sex work for a mean of 5.3 years; participants re- alence would be expected to increase with age, potentially con-

ported a mean of 15.7 paying clients per week and a mean charge founding its associations with other infections more common in

of 133.3 Kenyan shillings ($2.19 USD; table 1). STIs and BV were younger women. An additional analysis was therefore per-

common at baseline. The mean duration of clinical follow-up formed, with age added to the stratified model (as age less than

for participants was 2.1 years (773.7 days; range, 0.51,608 days). the mean cohort age of 28.8 years or age greater than or equal to

1694 JID 2007:196 (1 December) Kaul et al.

Table 2. Association of prevalent herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection and altered vaginal

flora with the incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

Incidence, no. of cases / 100 person-years

(no. of casesa)

HSV-2 IgG seronegative HSV-2 IgG seropositive

Coinfection (N 94) (N 322) Adjusted IRR 95% CI

Vaginal candidiasis 12.2 (30) 18.9 (129) 1.1b 0.71.7

Neisseria

gonorrhoeae 7.5 (13) 13.1 (67) 4.3b 1.512.2

Chlamydia

trachomatis 12.6 (22) 14.2 (73) 1.0b 0.61.7

Trichomonas vaginalis 5.7 (14) 17.7 (121) 2.3b 1.34.2

Treponema pallidum 0.8 (2) 5.1 (35) 4.7b 1.119.9

Never had bacterial Ever had bacterial

vaginosis vaginosis

(N 128) (N 288)

Vaginal candidiasis 15.5 (30) 20.4 (129) 1.3c 0.91.9

N. gonorrhoeae 13.6 (18) 12.1 (52) 0.8c 0.51.4

C. trachomatis 8.8 (12) 15.3 (79) 2.1c 1.13.8

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

T. vaginalis 2.4 (5) 20.0 (129) 8.0c 3.219.8

T. pallidum 3.3 (7) 4.1 (30) 1.0c 0.52.4

NOTE. CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio,

a

Parentheses show the total number of cases per group observed during follow-up.

b

Stratified for sexual risk-taking, antibiotic use (ie, azithromycin), and ever having had bacterial vaginosis during clinical

follow-up.

c

Stratified for sexual risk-taking, antibiotic use (ie, azithromycin), and HSV-2 infection status.

28.8 years). Again, no association was found between HSV-2 Subgroup analysis of BV associations restricted to those par-

infection and C. trachomatis acquisition (IRR, 1.1 [95% CI, 0.6 ticipants who were not infected with HSV-2 at baseline and who

1.9]; P .7). remained so throughout follow-up (N 94) was not possible,

As reported elsewhere [11], prevalent HSV-2 infection was because no participants in the HSV-2negative, BV-negative

strongly associated with HIV acquisition in a Cox regression group acquired C. trachomatis infection or syphilis during follow

model adjusting for study arm (ie, azithromycin use) and sexual up, precluding a regression analysis using these endpoints.

risk-taking (rate ratio [RR], 5.8 [95% CI, 1.527.1]; P .001).

BV and STI incidence. The impact of ever having had BV DISCUSSION

on STI incidence was examined among participants with stable

HSV-2 serostatus. A total of 288 (69%) of 416 participants with It is increasingly apparent that HSV-2 infection acts as an im-

at least 1 episode of laboratory-confirmed BV were compared portant cofactor in the HIV/AIDS pandemic. HSV-2 infection

with 128 (31%) of 416 participants who had never had BV (table increases the frequency of HIV transmission from HIVHSV-2

2). Again, no association was seen with vaginal candidiasis. In coinfected individuals [16], as well as increasing susceptibility to

contrast to HSV-2 infection, BV was not associated with an in- HIV acquisition by approximately 3-fold in HSV-2infected

creased incidence of infection with N. gonorrhoeae (IRR, 0.8 men and women from the general population [1], and by as

[95% CI, 0.51.4]; P .6) or syphilis (IRR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.5 much as 6-fold in HSV-2-infected female sex workers [11]. This

2.4]; P .9). However, BV was associated with increased rates may relate either to micro-ulceration or macro-ulceration of the

of infection with both C. trachomatis (IRR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.1 genital mucosa, or to HSV-2 infectionassociated increases in

3.8]; P .02) and T. vaginalis (IRR, 8.0 [95% CI, 3.219.8]; the number of mucosal HIV target cells, specifically CCR5-

P .0001). These associations remained significant when the expressing CD4 T cells and/or DC-SIGN expressing dendritic

analysis was restricted to participants who did not have BV at cells [6]. On this basis, clinical trials of HSV-2 suppression as a

enrollment and had stable HSV-2 serostatus (N 190); an in- strategy to reduce HIV sexual transmission are ongoing [17].

creased incidence was still observed for both C. trachomatis in- Other genital tract infections may also enhance the risk of sexual

fection (IRR, 2.4 [95% CI, 1.2 4.8]; P .02) and T. vaginalis HIV acquisition and secondary transmission [8]; these include

infection (IRR, 9.8 [95% CI, 3.527.1]; P .001) in those par- BV and N. gonorrhoeae, T. pallidum, H. ducreyi, and T. vaginalis

ticipants with incident BV during follow-up. infections, although treatment and/or prevention of these infec-

Herpes Simplex 2 and STI Incidence JID 2007:196 (1 December) 1695

tions as a strategy to prevent HIV acquisition has met with mixed 23], in part through the induction of proinflammatory cyto-

success [11, 18 20]. kines, and HSV-2 infection is also associated with NFB

Our data clearly show, for the first time, to our knowledge, induction [24] and alterations in cervical immune cell popula-

that chronic HSV-2 infection is not only associated with an in- tions and activation status [6]. In vitro, NFB induction en-

creased incidence of HIV infection, but also with an increased hanced infection by N. gonorrhoeae [7], suggesting a mechanism

incidence of both sexually transmitted and nonsexually trans- for HSV-2associated increases in rates of gonorrhea acquisi-

mitted genital infections, specifically N. gonorrhoeae infections, tion. Increased susceptibility to HIV may relate to direct genital

T. pallidum infections, and T. vaginalis infections. BV, a distur- macro-ulceration or micro-ulceration during HSV-2 reactiva-

bance in the vaginal microflora that tends to be recurrent, has tion, as well as to the increased numbers of mucosal HIV target

itself been associated with increased susceptibility to HSV-2 in- cells (CCR5 CD4 T cells, and DC-SIGN dendritic cells)

fection [9], as well as to HIV infection [8] and other STIs [10], present, even in the absence of HSV-2 reactivation [6]. The

perhaps by altering the genital tract cytokine milieu or by en- pathogenesis of T. vaginalis infection is less well understood, and

hancing HIV replication [20]. We observed an association be- how HSV-2 infection may enhance this process is not clear. The

tween prevalent HSV-2 infection and the presence of BV at en- complexity of local interactions between mucosal immunology

rollment, and also a prospective association between HSV-2 and various genital coinfections in vivo presents a significant obsta-

infection and new BV episodes. However, we believe that the cle to elucidating the immunopathogenesis of HSV-2associated

nature of BV as a waxing and waning imbalance of vaginal flora increases in STI acquisition in a real-world setting.

makes any analysis of the causes of incident BV difficult, if not Although we adjusted our analysis for reported sexual risk-

impossible, because the direction of causality cannot be deter- taking, this is only a proxy for true risk, and it is not possible to

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

mined with confidence. Nonetheless, there is clearly an associa- entirely rule out residual confounding. However, reported sex-

tion between rates of HSV-2 infection and BV, and between each ual risk-taking has been validated in this cohort as a marker for

of these and the incidence of several STIs, so that each may con- acquisition of both STIs [13] and HIV infection [11]. In addi-

found analysis of the impact of the other. We therefore stratified tion, no relationship was seen between HSV-2 infection and C.

our analysis of HSV-2 infection status and STI incidence on the trachomatis acquisition, although the latter was strongly linked

basis of BV at any time (either symptomatic or asymptomatic) to reported sexual risk-taking in this cohort [13]. Therefore, we

during clinical follow-up, as well as on the basis of reported sex- believe that behavioral confounding is less likely than a true bi-

ual risk-taking and study arm (ie, azithromycin vs placebo), and ological effect as an explanation for the strong associations seen

we continued to find strong associations between HSV-2 infec- between HSV-2 infection and subsequent STI acquisition.

tion and the subsequent acquisition of N. gonorrhoeae, T. palli- Nonetheless, should chronic HSV-2 infection have a broad effect

dum, and T. vaginalis. on STI susceptibility, given the important implications of these

In addition, after controlling for HSV-2 infection status, we findings for future research, it will be vital for future confirma-

were able to confirm the strong association previously demon- tory studies to definitively rule out behavioral confounders by

strated between BV and the incidence of infection with C. tra- including a careful assessment of sexual risk behavior. In this

chomatis [10], and a particularly strong association with incident study, testing for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), which is

T. vaginalis infection was also apparent. However, after control- responsible for an increasing proportion of genital herpes cases

ling for HSV-2 infection, we did not find any association be- in developed countries [25], was not performed. We are there-

tween BV and incidence of infection with N. gonorrhoeae . This fore not able to comment on the prevalence of HSV-1, or on any

may relate to differences in cohort or methodology between our possible association between HSV-1 and rates of HIV infection

study and others [10], but another possibility is that previously and STI acquisition.

described associations may have been confounded by the pres- In summary, chronic HSV-2 infection in this cohort of Ken-

ence of HSV-2 infection. What is clear is that future cohort stud- yan female sex workers was strongly associated with an increased

ies will need to control for the presence of numerous genital tract incidence of several genital infections, including HIV infection,

infections, including HSV-2 infection, BV, and others. Ulti- gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis, and with significant perturba-

mately, proving causation as it applies to the relationship of ei- tions in vaginal microflora. Prevention of HSV-2 infection, or

ther HSV-2 infection or BV with STI susceptibility will require chronic suppression of HSV-2 recurrence, as well as suppression

randomized clinical trials that target therapeutic and/or vaccine of BV, should be tested as strategies to prevent the acquisition of

interventions at a single factor (either BV or HSV-2 infection), multiple STIs, not just HIV infection.

and only that factor.

Our study does not permit elucidation of the biological basis MEMBERS OF THE KIBERA HIV STUDY GROUP

for enhanced STI susceptibility due to HSV-2 infection and/or

BV. Both infections have been described as inducing quite pro- Bolette Bossen, Grace Kamunyo, Ruth Wanguru, Rachel Mwak-

found immunological changes in the female genital tract [6, 21 isha, Grace Waithira, Daniel Nganga, Cornelius Nyambogo,

1696 JID 2007:196 (1 December) Kaul et al.

John Ombette, Jane Njeri, Isaiah Onyango, Bing Li, Dr. Isaac 12. Kaul R, Kimani J, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Risk factors for genital ulcerations

in Kenyan sex workers: the role of human immunodeficiency virus type

Malonza, Dr. Ian Maclean, Dr. Francis Mwangi, Refik Saskin,

1 infection. Sex Transm Dis 1997; 24:38792.

Judy Strauss, and Dr. Samuel Kariuki. 13. Kaul R, Kimani J, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Reduced HIV risk-taking and low

HIV incidence after enrollment and risk- reduction counseling in a sex-

Acknowledgments ually transmitted disease prevention trial in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir

Immune Defic Syndr 2002; 30:69 72.

We thank the members of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board, ac- 14. Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized trial of the duration of ther-

knowledge the support of the Nairobi City Council, and give special thanks apy with metronidazole plus or minus azithromycin for treatment of

to all the Kibera study participants for their enthusiasm and support. symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:21319.

15. Adams EJ, Charlett A, Edmunds WJ, Hughes G. Chlamydia trachomatis

in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and analysis of prevalence

References studies. Sex Transm Infect 2004; 80:354 62.

16. Ouedraogo A, Nagot N, Vergne L, et al. Impact of suppressive herpes

1. Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes therapy on genital HIV-1 RNA among women taking antiretroviral

RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men therapy: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS 2006; 20:230513.

and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal stud- 17. Celum CL, Robinson NJ, Cohen MS. Potential effect of HIV type 1

ies. AIDS 2006; 20:73 83. antiretroviral and herpes simplex virus type 2 antiviral therapy on trans-

2. Weiss H. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the mission and acquisition of HIV type 1 infection. J Infect Dis 2005;

developing world. Herpes 2004; 11(Suppl 1):24A35A. 191(Suppl 1):S10714.

3. Wald A. Herpes simplex virus type 2 transmission: risk factors and virus 18. Kamali A, Kinsman J, Nalweyiso N, et al. A community randomized

shedding. Herpes 2004; 11(Suppl 3):130A37A. controlled trial to investigate impact of improved STD management and

4. Wald A, Corey L. How does herpes simplex virus type 2 influence hu- behavioural interventions on HIV incidence in rural Masaka, Uganda:

man immunodeficiency virus infection and pathogenesis? J Infect Dis trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health 2002;

2003; 187:1509 12.

Downloaded from http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 14, 2016

7:1053 63.

5. Corey L, Wald A, Celum CL, Quinn TC. The effects of herpes simplex 19. Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, et al. Impact of improved treatment of

virus-2 on HIV-1 acquisition and transmission: a review of two overlap- sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: ran-

ping epidemics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 35:435 45. domised controlled trial. Lancet 1995; 346:530 6.

6. Rebbapragada A, Wachihi C, Pettengell C, et al. Negative mucosal syn- 20. Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. A randomized, commu-

ergy between Herpes simplex type 2 and HIV in the female genital tract. nity trial of intensive sexually transmitted disease control for AIDS pre-

AIDS 2007; 21:589 98. vention, Rakai, Uganda. AIDS 1998; 12:121125.

7. Muenzner P, Naumann M, Meyer TF, Gray-Owen SD. Pathogenic Neis- 21. Cohen CR, Plummer FA, Mugo N, et al. Increased interleukin-10 in the

seria trigger expression of their carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellu- endocervical secretions of women with non-ulcerative sexually trans-

lar adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1; previously CD66a) receptor on mitted diseases: a mechanism for enhanced HIV-1 transmission? AIDS

primary endothelial cells by activating the immediate early response 1999; 13:32732.

transcription factor, nuclear factor-kappaB. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:2433140. 22. Hedges SR, Barrientes F, Desmond RA, Schwebke JR. Local and systemic

8. Corbett EL, Steketee RW, ter Kuile FO, Latif AS, Kamali A, Hayes RJ. cytokine levels in relation to changes in vaginal flora. J Infect Dis 2006;

HIV-1/AIDS and the control of other infectious diseases in Africa. Lan- 193:556 62.

cet 2002; 359:2177 87. 23. Yudin MH, Landers DV, Meyn L, Hillier SL. Clinical and cervical cyto-

9. Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Lurie JG, Hillier SL. Association kine response to treatment with oral or vaginal metronidazole for bac-

between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bac- terial vaginosis during pregnancy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol

terial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:319 25. 2003; 102:52734.

10. Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Bacterial 24. Mosca JD, Bednarik DP, Raj NB, et al. Activation of human immuno-

vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia deficiency virus by herpesvirus infection: identification of a region

trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:663 68. within the long terminal repeat that responds to a trans-acting factor

11. Kaul R, Kimani J, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Monthly antibiotic chemopro- encoded by herpes simplex virus 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987; 84:

phylaxis and incidence of sexually transmitted infections and HIV-1 7408 12.

infection in Kenyan sex workers: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 25. Nilsen A, Myrmel H. Changing trends in genital herpes simplex virus

2004; 291:2555 62. infection in Bergen, Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000; 79:693 6.

Herpes Simplex 2 and STI Incidence JID 2007:196 (1 December) 1697

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Sik Gigi Mayang 23 April 2016Documento265 pagineSik Gigi Mayang 23 April 2016Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Academic MisconductDocumento38 pagineAcademic MisconductSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Herpes Simplex Virus Suppression WithDocumento9 pagineHerpes Simplex Virus Suppression WithSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ijm 4 204Documento6 pagineIjm 4 204Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nej Mo A 1410649Documento10 pagineNej Mo A 1410649Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Geographic Tongue and Fissured Tongue in 348 Patients With Psoriasis: Correlation With Disease SeverityDocumento8 pagineGeographic Tongue and Fissured Tongue in 348 Patients With Psoriasis: Correlation With Disease SeveritypancholarpancholarNessuna valutazione finora

- HerbalDocumento9 pagineHerbalSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methods 3Documento35 pagineResearch Methods 3Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Long-Term Valacyclovir Suppressive Treatment After Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 MeningitisDocumento10 pagineLong-Term Valacyclovir Suppressive Treatment After Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 MeningitisSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Artikel Kelompok 2Documento10 pagineReview Artikel Kelompok 2Yuanita Hasna RahmadhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 2686 PDFDocumento10 pagine2686 PDFSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Coinfection With Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2Documento8 pagineCoinfection With Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cabt 13 I 2 P 258Documento5 pagineCabt 13 I 2 P 258Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Vol9 (12) No1 pg88-93Documento6 pagine2014 Vol9 (12) No1 pg88-93Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- C H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaDocumento15 pagineC H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2686 PDFDocumento10 pagine2686 PDFSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Immune Response and Candidal Colonisation in Denture Associated Stomatitis 2155 9899.1000178Documento7 pagineImmune Response and Candidal Colonisation in Denture Associated Stomatitis 2155 9899.1000178Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Vol9 (12) No1 pg88-93Documento6 pagine2014 Vol9 (12) No1 pg88-93Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ijm 4 204Documento6 pagineIjm 4 204Sisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- C H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaDocumento15 pagineC H C /C (C L) : Hronic Yperplastic Andidosis Andidiasis Andidal EukoplakiaSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Report: A.N Atypical Pathway of Infection in An Adolescent W TH A Deep Neck Space AbscessDocumento4 pagineCase Report: A.N Atypical Pathway of Infection in An Adolescent W TH A Deep Neck Space AbscessSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Periadontitis As PDFDocumento6 pagineChronic Periadontitis As PDFAhtarunnisa Fauzia HanifaNessuna valutazione finora

- Print St2 AnatomiDocumento1 paginaPrint St2 AnatomiSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- B.ing GJDocumento13 pagineB.ing GJSisca Rizkia ArifiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Prima HidayaningtyasDocumento13 paginePrima Hidayaningtyasv3_nanaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- STD Epidemic: Understanding STDs and HIV/AIDSDocumento7 pagineSTD Epidemic: Understanding STDs and HIV/AIDSmakaylaNessuna valutazione finora

- Condom UseDocumento2 pagineCondom UseMuhamad FakhrullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Mapúa University: 3F Admin. Bldg. Intramuros, Manila 247 - 5000, Loc. 1302, 1303Documento1 paginaMapúa University: 3F Admin. Bldg. Intramuros, Manila 247 - 5000, Loc. 1302, 1303Deo Kristofer OndaNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Facts ON HIV: By: Ms. May Jacklyn C. Radoc-Samson, RN, LPT, MancDocumento20 pagineBasic Facts ON HIV: By: Ms. May Jacklyn C. Radoc-Samson, RN, LPT, MancMay Jacklyn RadocNessuna valutazione finora

- SHP Homeopathy As A Treatment For HIV and Aids Session 1Documento14 pagineSHP Homeopathy As A Treatment For HIV and Aids Session 1lghmshari100% (1)

- Acute Cervicovaginitis.Documento23 pagineAcute Cervicovaginitis.Kevin VillagranNessuna valutazione finora

- JURNAL GonoreDocumento20 pagineJURNAL GonoreRuni Arumndari100% (1)

- Who Recommends Assistance For People With Hiv To Notify Their PartnersDocumento2 pagineWho Recommends Assistance For People With Hiv To Notify Their PartnerstashoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaginal Discharge GuidelineDocumento4 pagineVaginal Discharge GuidelineGung Bagvs SaputraNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal NoviaDocumento13 pagineJurnal NoviaNovia Syahreni Tarigan0% (1)

- STIsDocumento31 pagineSTIsAbdulmumin UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Saza E Maut (Video) : Aids Funny Video - Youtube - FLV Aids Funny Video - Youtube - FLVDocumento33 pagineSaza E Maut (Video) : Aids Funny Video - Youtube - FLV Aids Funny Video - Youtube - FLVKhizer HumayunNessuna valutazione finora

- FICTC Monthly Reporting Format For WBFPTDocumento1 paginaFICTC Monthly Reporting Format For WBFPTSWAPAN KUMAR SARKAR100% (5)

- WHO and HIV 30 YearsDocumento1 paginaWHO and HIV 30 YearsdivillamarinNessuna valutazione finora

- HIV Awareness Survey QuestionnaireDocumento3 pagineHIV Awareness Survey QuestionnaireSean Patrick Razo0% (1)

- Make and Submit A 200-300-Word Essay Reflection On AIDS On Prevention and Control MeasuresDocumento2 pagineMake and Submit A 200-300-Word Essay Reflection On AIDS On Prevention and Control MeasuresBunnie AlphaNessuna valutazione finora

- STD Treatment Guideline HCPDocumento72 pagineSTD Treatment Guideline HCPKomang Adhi AmertajayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syphilis Fact Sheet PressDocumento2 pagineSyphilis Fact Sheet Pressmahaberani_zNessuna valutazione finora

- Everything You Need To Know About Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDS)Documento18 pagineEverything You Need To Know About Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDS)Myke KierkierNessuna valutazione finora

- Chlamydia Power PointDocumento19 pagineChlamydia Power PointAnne McfarlandNessuna valutazione finora

- MODULE 4 (Basics of STI, HIV & AIDS)Documento45 pagineMODULE 4 (Basics of STI, HIV & AIDS)Mark Johnuel Duavis100% (2)

- Filipino RRLDocumento4 pagineFilipino RRLAndreNicoloGuloyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gonorrhea Case Study 2009Documento4 pagineGonorrhea Case Study 2009Garrett Batang100% (3)

- Gonorrhea: by Siena Kathleen V. Placino BSN-IV Communicable Disease Nursing C.I.: Dr. Dario V. SumandeDocumento38 pagineGonorrhea: by Siena Kathleen V. Placino BSN-IV Communicable Disease Nursing C.I.: Dr. Dario V. SumandeSiena100% (1)

- Review Journal Evaluasi Program Pencegahan Penularan HIV dari Ibu ke AnakDocumento24 pagineReview Journal Evaluasi Program Pencegahan Penularan HIV dari Ibu ke AnakvinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Who HerpesDocumento56 pagineWho HerpesYanna RizkiaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Resume (Circumcision)Documento1 paginaEnglish Resume (Circumcision)Siti WidyawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- PPP IctcDocumento1 paginaPPP IctcT Myano OdyuoNessuna valutazione finora

- Promote Safe Sex and ContraceptivesDocumento3 paginePromote Safe Sex and ContraceptivesCalvin YusopNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Education Cuf Teaching Guide March 8Documento2 pagineHealth Education Cuf Teaching Guide March 8Bree BobbadillaNessuna valutazione finora