Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

'From Gordian III To The Gallic Empire (AD 238-74) ' in W E Metcalf (Ed.), Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, Oxford University Press 2012 PDF

Caricato da

Dimitris BofilisTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

'From Gordian III To The Gallic Empire (AD 238-74) ' in W E Metcalf (Ed.), Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, Oxford University Press 2012 PDF

Caricato da

Dimitris BofilisCopyright:

Formati disponibili

chapter 28

FROM GORDIAN III TO

THE GALLIC EMPIRE

(AD 238274)

roger bland

From Aurelius Ptolemaeus also called Nemesianus, strategus of the Oxyrhynchite

nome. Since the public officials have assembled and accused the bankers of the

banks of exchange of having closed them on account of their unwillingness to

accept the divine coins of the Emperors, it has become necessary that an injunc-

tion should be issued to all the owners of the banks to open them, and to accept

and exchange all coin except the absolutely spurious and counterfeit, and not only

to them, but to all who engage in business transactions of any kind whatever,

knowing that if they disobey this injunction they will experience the penalties

ordained for them previously by his highness the Prefect [of Egypt]. (POxy 1411,

AD 260, cited by Burnett 1987: 104)

This letter, from a worried official of the administrative district, or nome, of

Oxyrhynchus in Egypt in AD 260 would seem to indicate that there had been a total

collapse of trust in the imperial coinage in Egypt. The letter explicitly refers to the

large number of counterfeit coins in circulation, but the loss of trust was presumably

largely due to the debasement of the coinage at this time. The confusion would have

been further complicated by the breakdown in imperial authority that resulted from

the capture of Valerian by the Sasanians in 260, a uniquely shocking event in Roman

history, which led Macrianus and Quietus to assume power in Egypt and Syria.

So this document encapsulates some of the main themes of the coinage of this

period: debasement, problems of counterfeiting, and a rapid turnover of rulers

(during this period coins were issued in the names of no fewer than 35 individuals,

and we know that more usurpers claimed power without actually producing coins).

Traditionally, numismatic scholarship has regarded this period as one of decline,

0001341912.INDD 514 9/24/2011 7:08:20 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 515

about which there was little positive to be said, and it was usually skated over in a

few brief sentences. Within the last fifty years, however, numismatists have reas-

sessed the coinage of this period, stimulated largely by the great quantity of coin

finds, both hoards and as site finds, and it is possible to see it as a period when, as a

result of debasement, coins came to be used far more widely than had ever been the

case before.

The theme of this chapter is to trace the collapse of the currency system estab-

lished first by Augustus and refined by his successors such as Nero. This may be

characterized as

A trimetallic coinage with fixed relationships between coinages in gold,

silver and bronze

Coinage in Roman denominations produced mainly at the mint of Rome

and supported by

An extensive series of provincial silver and civic bronze coinages produced

to local standards

By the end of this period can be seen the beginnings of what may be characterized

as the Late Roman system (further developed under Aurelian, Diocletian, and

Constantine), which may be characterized by

A token base metal or bronze coin, together with gold coins circulating at

bullion value

The cessation of both the early imperial bronze coinage of sestertii, dupon-

dii, and asses, whose production was rendered uneconomic by the debase-

ment of the silver coinage, and of the provincial silver and bronze coinages

Their replacement with a uniform series of coins of Roman denominations

produced at a network of mints around the empire.

At the same time, there were profound changes in the iconography of the coinage:

the tradition of naturalistic ruler portraiture (which Augustus had inherited from

Hellenistic models) with a varied series of reverse designs, often topical or in other

ways reflecting the tastes of the individual emperor, gave way to portraits that are

intended to represent an idealized view of the ruler and standardized reverse designs

that only rarely refer to current events.

The Monetary System

Silver

In their brief reign (AprilAugust 238) Balbinus and Pupienus had revived the

denomination that has been traditionally known as the antoninianus but should

better be termed radiate (fig. 28.1).1 This had been introduced by Caracalla in AD

215 and was probably intended as a double denarius, although it only contained 1.6

0001341912.INDD 515 9/24/2011 7:08:20 PM

516 the roman world

Fig. 28.1

times as much silver as the denarius. The radiate was issued alongside denarii by

Caracallas successors Macrinus (217218) and Elagabalus (218222), but the latter

stopped issuing radiates after a year. Thereafter, for the next nineteen years only

denarii were struck under Severus Alexander (222235), Maximinus (235238), and

Gordian I and II (238).

There has been much discussion about the relationship between the radiate and

the denarius, since it must have been obvious to users at the time that the intrinsic

value of the new denomination was much less than twice that of the denarius, but

it seems that Caracalla, Macrinus, and Elagabalus must have intended it to be a

double denarius coin. Users would presumably have preferred the old denarius

whenever they could, and the historian Dio Cassius characterizes Caracallas coin-

age as untrustworthy (He [Caracalla] likewise published outright to the world

some of his basest deeds, as if they were excellent and praiseworthy, whereas others

he revealed unintentionally through the very precautions which he took to conceal

them, as, for example, in the case of money; Dio 78.15, 1).

It seems likely, in fact, that subsequent rulers would have found it difficult, if not

impossible, to enforce a 2:1 relationship between the radiate and the denarius while the

radiate was not being issued, and so the two denominations may well have been

exchanged at the more natural ratio of 1.5:1 after 238 (Bland 1996). When Balbinus and

Pupienus revived the radiate in 238, this denomination rapidly replaced the denarius

completely. Apart from two issues of denarii struck by Gordian III in AD 241 (fig. 28.2;

Elks 1972), denarii were thereafter only produced on a very small scale, perhaps just for

ceremonial use, until Aurelian (270275) revived the denomination. Quinarii (half

denarii) were also produced in small quantities throughout the period, and these, too,

probably had a ceremonial use (fig. 28.3; King 1978, 2007).

It is sometimes suggested that Trajan Decius (249251) demonetized the den-

arius, on the grounds that a number of Deciuss radiates are found overstruck on

earlier denarii, chiefly of the Severan period (fig. 28.4; Burnett 1987). Hoards,

Fig. 28.2 Fig. 28.3

0001341912.INDD 516 9/24/2011 7:08:20 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 517

Fig. 28.4

however, do not seem to support this, as many hoards with latest coins dating to the

250s and 260s contain significant proportions of denarii (Bland 1996: 8490). It is

quite possible that the mint authorities in Deciuss reign found the earlier denarii a

convenient source of material for striking new radiates, without necessarily deliber-

ately demonetizing the denomination.

After 238 the radiate went through a series of weight reductions and debase-

ments, shown in fig. 28.52, so that from being a coin of around 4.5 g with 42% silver

at the start of Gordians reign (i.e., 1.9 g of silver), it weighed no more than 3.4 g and

was 35% pure under Aemilian (253; 1.2 g of silver). After 253, the decline accelerated:

by the end of Valerians reign in AD 260, the radiate had become a coin of 2.9 g with

15% of silver (0.4 g of silver; fig. 28.5) and by the end of Gallienuss reign in AD 268,

its weight was 2.9 g and silver fineness around 2.5% (0.07 g of silver; fig. 28.6) before

a final decline in the reigns of Claudius II (26870; fig. 28.7) and Quintillus (270) to

2.5 g with a purity of 2.5% (0.06 g of silver; Walker 1978; Tyler 1975; Besly and Bland

1983; Cope et al. 1997; for a useful summary see Harl 1996: 130).

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

8

0

2

4

6

8

0

2

4

6

8

0

2

4

6

8

0

2

4

6

8

0

2

23

24

24

24

24

24

25

25

25

25

25

26

26

26

26

26

27

27

27

27

27

28

28

Fig. 28.52

0001341912.INDD 517 9/24/2011 7:08:22 PM

518 the roman world

Fig. 28.5 Fig. 28.6

Fig. 28.7

Diocletians Price Edict attests a relative value of silver to copper of 100:1 (Frank

1940), so even with a silver fineness of 2.5% the silver element of the radiate would

have been two and a half times more valuable than the base metal element.

However, the true picture is more complicated. Postumus, who seized control

of the western provinces of Gaul, Germany, Spain, and Britain after the capture of

Valerian in AD 260 (Knig 1981; Drinkwater 1987), deliberately produced coins to a

higher standard than Gallienus, at least for the first years of his reign, when he pro-

duced radiates at a weight of 3.3 g to a fineness of 1520% (fig. 28.8). At the end of

his reign he had to lower the silver standard to 8%, and his successors, Laelian (269;

fig. 28.9), Marius (269), Victorinus (269271; fig. 28.10), and Tetricus (271274;

fig. 28.11), had to debase the coinage and reduce the weight even more, so that under

Tetricus the radiate was a coin of 2.4 g with only 1.5% of silver and much poorer

than the contemporary coins of Aurelian, who had instituted a series of reforms of

the coinage (Besly and Bland 1983).

Fig. 28.8 Fig. 28.9

Fig. 28.10 Fig. 28.11

0001341912.INDD 518 9/24/2011 7:08:22 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 519

It is also becoming clear, as more analyses are published, that the different mints

that had started to operate from the 250s were not necessarily striking coins to a

uniform weight standard or purity. Coins from eastern mints seem to have consis-

tently contained a higher silver content than their counterparts from Rome.

For example, the radiates issued by Gordian at Antioch in AD 242244 have an aver-

age silver fineness of 43.5%, compared with an average fineness of 36.8% for the

contemporary radiates of Rome (Bland 1991a). Since both coinages have the same

average weight, the eastern coins had 15% more silver than the Roman ones. An

even greater disparity was observed by Tyler in the case of the radiates of Gallienuss

sole reign from Antioch (Tyler 1975; fig. 28.12): the last two issues of Gallienus of AD

266268 from Antioch have an average silver fineness of 9.9 and 9.3%, respectively,

whereas the contemporary coins of Rome are only 2.5% fine. The mint maintained

this level of fineness under Claudius and Vabalathus (Cope et al. 1997; fig. 28.13).

Aurelians reform established a uniform silver content of just under 5% for the new

radiate at all mints, but it is notable that under Diocletians reform, the reformed

nummi from eastern mints again have a higher silver content than those from west-

ern mints (Cope at al. 1997). Under Valerian and Gallienus other branch mints, such

as the mints of Gaul, Milan, and Siscia, also generally issued coins with a higher

silver content than Rome, although the differences were much less. In general, one

has a picture of considerable dislocation in Gallienuss reign (see, for example, Gbl

2000), but the consistently higher fineness of radiates and, later, reformed nummi,

from eastern mints remains a mystery. However, it must have influenced circulation

patterns of these coins (Howgego 1996).

But what caused this massive debasement? Almost certainly the main cause was

the lack of new bullion, partly the result of the exhaustion of the principal silver

mines, such as those in northern Spain ( Jones 1980), and partly because of the out-

flow of large payments, for example the payment of 500,000 denarii that Shapur

claims to have received from Philip I in AD 244 (Millar 1993:154; fig. 28.14)2 or pay-

ments made to tribes on the Rhine and Danube frontiers.

Fig. 28.12 Fig. 28.13

Fig. 28.14

0001341912.INDD 519 9/24/2011 7:08:24 PM

520 the roman world

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

7

8

1

0

3

2

8

0

5

6

7

0

8

4

8

8

7

41

54

69

96

11

13

16

18

19

22

23

26

27

29

31

33

34

36

37

38

2

Fig. 28.53

A consequence of the debasement was a massive increase in the volume of coin

production, as can be seen from fig. 28.53. This can be seen from three different

types of evidence: from the patterns of coin hoards, of which there was an enor-

mous increase between the late 250s and the 290s (Callu 1969; Abdy 2002a); from

the patterns of site finds (Reece 1991, 1995, 2002 and 2003); and from die studies.

In an article published in 1987, Depeyrot and Hollard produced a graph that set

the total numbers of coins by period between 238 and 282 from a sample of 65

hoards (containing some 350,000 coins) against the silver content of those coins

(28.52). This shows that while the volume of coins rose to a peak in the period

270274 (chiefly accounted for by the issues of Tetricus), the amount of silver being

coined was on a declining trend throughout the period.

Although coin hoards can contain great numbers of coins (for example, the

Rka-Devnia hoard from Bulgaria, which closed about 250, contained at least 81,044

coins: Mouchmov 1934), it is unsafe to rely on hoards alone as an index of coin pro-

duction. This is because the only hoards that survive today are those that were not

recovered in antiquity, and it is fair to assume that there would have been a higher

rate of nonrecovery in periods of disturbance and invasion than in more peaceful

times. Arguably, therefore, site finds provide a more accurate reflection of coin pro-

duction than hoards, although they, too, contain their own bias, since the coins lost

on sites can be assumed to contain a high proportion of low-value denominations,

as someone who dropped a gold aureus would presumably make much greater

efforts to recover it than the person who dropped a debased radiate. Thus it is that

plated forgeries of denarii, which are generally only present in very small quantities

0001341912.INDD 520 9/24/2011 7:08:25 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 521

in coin hoards, are actually more common than regular denarii amongst site finds

from Britain.

Nevertheless, the pattern of site finds, illustrated by fig. 28.53, which represents

Richard Reeces summary of the typical British site (based on a large sample of

sites studied), also demonstrates that there was a great increase in coin loss in the

period after 260 (Reece 1995). In fact, in many sites in Britain, especially the smaller

rural sites, the earliest coins are the debased radiates of the period 260274.

Die studies also confirm the evidence of the coin finds for a great increase in

coin production at this period. A die study of the coinage of the Gallic usurper

Laelian (fig. 28.9), who rebelled against Postumus at the end of his reign, has shown

that the coinage was struck from an estimated 56 obverse dies (Gilljam 1982, 1986).

In the same study, Gilljam collected together figures of the occurrence of coins of

Laelian in hoards: in a sample of 82 hoards, he found 286 coins of Laelian, compared

with 81,027 coins of Victorinus (fig. 28.10), who held power in the Gallic Empire for

two years from 269 to 271.3 Assuming that the coins of both rulers were equally rep-

resented in hoards, as seems reasonable, this suggests that coins of Victorinus are

283 times as common as those of Laelian, implying that Victorinus may have used

15,850 obverse dies, an extremely high number. If a figure of 30,000 coins per obverse

die is adopted for these coins,4 this would suggest a mintage of 476 million radiates

over the course of the reign, or perhaps 48 million a week.5 In the fourth century, it

would seem that coin production was even higher, judging by the evidence of site

finds, but otherwise coin production on this scale was not equaled until quite

recently.6

There is thus a good case for saying that the enormous increase in coin produc-

tion during this period, traditionally seen as the result of the collapse of the early

imperial coinage system in the teeth of rampant inflation, in fact had the positive

effect of spreading the coin-using economy far wider than had ever been the case

before, at least in the northwestern provinces of the empire. It should be noted that

coin finds from the western Mediterranean area, which are still not as well pub-

lished as those from Gaul, Germany, and Britain, do not show a great leap in coin

loss at this period, as the coin-using habit had been far more widely spread at an

earlier period in the more developed economies of Spain, Italy, and Africa.

Gold

The gold coinage was also affected by the debasements of this period, although in a

different way (Bland 1996; Morrisson et al. 1985). It is possible to discern three sepa-

rate trends. The first, and most obvious, is the gradual reduction in weight of the

aureus. From Nero through Caracalla, this remained unchanged at an average of

7.25 g. In 216, Caracalla reduced the weight to 6.5 g; it is possible that there was a

brief attempt to restore the weight to 7.25 g under Macrinus and Elagabalus, but

after this time the aureus ceased to be struck to a consistent standard. Its mean

weight, however, fell steadily to 3.6 g in the reign of Trebonianus Gallus (251253),

while under Gallienus gold coins weighing no more than a gram were issued. Gallus

0001341912.INDD 521 9/24/2011 7:08:25 PM

522 the roman world

attempted to halt the slide by introducing a

new, heavier denomination (fig. 28.15), which

was continued by Valerian and Gallienus.

The second and related trend is that

from the beginning of the third century AD

Fig. 28.15 onward, gold coins were struck at increas-

ingly variable weights. In the first and second

centuries, and again in the fourth, the Roman minting authorities took care to

ensure that gold coins were struck at the same weight: for example, 95% of the aurei

of the reign of Commodus had weights within a band of a quarter of a gram (7.1

7.35 g). However, this strict control over the weights of individual pieces seems to

have been increasingly relaxed, and from Severus Alexanders reign the range of

weights of individual aurei widens greatly, with individual aurei ranging from 7.25

g down to 5.38 g (Bland 1996). This was to remain the pattern until Constantine

reformed the gold coinage in 310. Indeed, the spread of weights of individual coins

becomes so wide that by the reign of Valerian and Gallienus all attempts at main-

taining any standard seem to have broken down entirely, and gold coins weighing 1

g or less were produced in Gallienuss sole reign (fig. 28.16). Gallienuss contempo-

rary and rival, Postumus, produced heavier gold coins (fig. 28.17), but these, too,

were not issued to a consistent weight, and the same is true of Gallienuss successors

from Claudius II onward. However, none of them, Diocletian included, issued aurei

at the same consistency of weight that had obtained up until the end of the second

century.

The final event that overtook the gold coinage during the third century was that

it was debased. While the aureus continued to be struck at a fineness of 98% or bet-

ter down to 253, a sudden debasement took place under Valerian and Gallienus

(Morrisson et al. 1985). Twenty-two coins of this reign were analyzed and the results

varied from 99% down to as little as 66%, with a mean fineness of 89%. Under

Claudius, the fineness was restored to a mean of 94%; this was increased to 97% by

Aurelian.

These changes must have destroyed the exchange rate between the silver and

the gold coinage, fixed in the early empire at 25 denarii to an aureus; however, the

precise date at which this break occurred is less clear, although arguably it had

already been broken in Severus Alexanders reign (Bland 1996). Another view is that,

in broad terms, the aureus and radiate remained in step down to the reign of Valerian

and Gallienus and that the break occurred then (so Burnett 1987: 114; Kent 1973).

Fig. 28.16 Fig. 28.17

0001341912.INDD 522 9/24/2011 7:08:25 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 523

It is likely that the debasement of the gold coinage was the result of the scarcity

of gold bullion (just as silver had also become increasingly scarce at this time), and,

in contrast to the base silver coinage, the production of gold falls to a very low level

in the third century. This can best be demonstrated by single finds of gold coins

from the western empire (fig. 28.54).7 These data give us a unique insight into the

rhythm of production of gold coins throughout the period of the empire and show

how the quantity of gold coins lost fell to its lowest level between the reign of

Commodus (180192) and the accession of Diocletian in AD 284. Die studies help

to confirm this picture: in the reign of Trajan (98117) it is estimated that 50 reverse

dies per year were used for aurei (Duncan-Jones 1994: 144); under the Gallic Empire,

between 19 and 24 obverse dies for gold coins were used each year (Schulte 1983).

Bronze

The final element of the coinage to be discussed is the bronze coinage, which by this

period consisted of sestertii, dupondii, and asses (the smaller denominations,

semisses and quadrantes, had ceased to be struck by the middle of the second cen-

tury). All three denominations continued to be issued at the mint of Rome on a

regular basis and in significant quantities until the end of the reign of Valerian and

Gallienus (fig. 28.18), although they are only rarely found in the northwestern prov-

inces of the empire or in Asia (except for drachms of Lycia). It would seem that

most were destined to circulate in the Mediterranean and North Africa, and hoards

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

7

7

8

1

0

3

2

8

0

5

6

7

0

8

4

8

8

41

54

69

96

2

11

13

16

18

19

22

23

26

27

29

31

33

34

36

37

38

Fig. 28.54

0001341912.INDD 523 9/24/2011 7:08:26 PM

524 the roman world

Fig. 28.18 Fig. 28.19

from Gaul, Britain, and Germany show that in these provinces bronze coins from

the prolific issues of the late first and second centuries continued to circulate down

to the 260s.

There are some very rare issues of bronze asses of Valerian and Gallienus (fig.

28.19) and two usurpers in the East, Macrianus and Quietus (260261), which, from

the style of their portraits and the lack of the letters SC on the reverse, can be attrib-

uted to Antioch; but otherwise these denominations were only struck at Rome. This

is no doubt partly because large numbers of city mints were still striking bronze

issues down to the sole reign of Gallienus, when they ceased production.

Under Neros reform, sestertii and dupondii had been made of orichalcum, an

alloy of copper and zinc and thus differed in appearance from and had a greater

intrinsic value than asses, which were made of pure copper. This is why dupondii

were able to circulate at two asses, even though they were only very slightly heavier

than them. By the third century, however, sestertii and dupondii had ceased to con-

tain any zinc (Cope 1974), but they continued to circulate alongside asses, which

were by now made of exactly the same metal but were still worth half a dupondius.

By this period, therefore, the bronze coinage must have been purely fiduciary in

character.

Trajan Decius attempted a reform that consisted of the introduction of a large

radiate bronze coin weighing about 41 g, which must be a double sestertius (fig. 28.20;

his sestertii had an average weight of 23 g), and a small bronze coin, with a laureate

portrait, weighing 4.5 g, which is presumably a semis (fig. 28.21). However, this was a

short-lived experiment, as neither denomination survived the end of his reign.

Fig. 28.20 Fig. 28.21

0001341912.INDD 524 9/24/2011 7:08:26 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 525

The last major issue of bronze coins from the central empire was in the joint

reign of Valerian and Gallienus (253260), and by Gallienuss sole reign only a very

small number were minted. As with denarii, however, it seems that successive rul-

ers continued to mint very small quantities of bronze denominations (normally

laureate pieces presumably intended as asses) for ceremonial purposes. However,

in the so-called Gallic Empire in the northwestern provinces of the empire,

Postumus continued to produce bronze coins in significant quantities, at least for

the first half of his reign (Bastien 1967). It is hard to determine what denomina-

tions were issued, as the bronze coins all have radiate portraits and range in weight

from nearly 40 g (fig. 28.22) down to less than 10 g (fig. 28.23); imitations are also

very common. However, the unstoppable debasement of the radiate, which nomi-

nally at least was worth 8 sestertii, eventually made it uneconomical to continue

striking bronze coins.

Contemporary Copies

Forgeries were a feature of most ancient coinages, and at certain times, including

this period, copies were more prevalent than the official issues. It is necessary to

distinguish between two different types of ancient copies: (1) forgeries of gold or

silver coins that were intended to deceive, such as plated denarii (fig. 28.24), or

gilded denarii, and (2) unofficial copies of base metal coins that can never have been

intended to deceive, either because the standard of their die engraving was so crude

or they were so much smaller than the originals (fig. 28.25). It is now believed that

Fig. 28.22 Fig. 28.23

Fig. 28.24 Fig. 28.25

0001341912.INDD 525 9/24/2011 7:08:27 PM

526 the roman world

the latter copies were produced to fill gaps when the official mints were not produc-

ing coins of the right denomination, rather as token copper coins were produced in

England between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries (Boon 1988; King 1996). In

this period imitations of radiates, especially of the Gallic Empire, and of the post-

humous coins of Claudius II, the so-called barbarous radiates, are particularly com-

mon, and indeed at some sites they are considerably more numerous than official

coins (Reece 2002: 4849).

Mints

This period saw at the same time an expansion in the establishment of branch mints

striking radiates (and, in rare cases, aurei), while at the same time the large number

of provincial mints declined rapidly during the reigns of Valerian and Gallienus

(253268), with the last of them, Perge in Asia, ceasing to issue coins under Tacitus

(275276). (See fig. 28.22.)

The attribution of the coins of this period to their mints has probably been the

principal single area of concern for numismatists over the last 50 years. Fashions

change, and numismatists from Mattingly onward tended to ascribe all new series

of coins to different mints. More recently, though, scholars have become increas-

ingly aware that major mints such as Rome could issue coins in the style of a differ-

ent mint for circulation in a particular area, and that perhaps a rather smaller

number of major mints could produce coins for different markets (for examples see

Baldus 1969; Burnett and Craddock 1983).

At the start of the period, just two mints issued Roman denominations: Rome

and Antioch in Syria. It is probably true to say that Rome remained the principal

mint throughout the period covered by this chapter, although by the end its suprem-

acy was increasingly challenged by very large outputs from the main branch mints.

Rome was the only mint to strike the full range of denominations, in gold, silver,

and bronze, although gold coins are known from Antioch from the reign of Gordian

and the other branch mints increasingly struck in gold after 253.

Antioch had been a major center of coin production for most of the Roman

period, but sporadically rather than continuously, and until 253 it produced more

tetradrachms than Roman-style denarii or radiates. Under Gordian III, two major

issues of radiates were issued at Antioch, in 238239 (fig. 28.26) and again in 242244

(fig. 28.27), and both of these can probably be associated with imperial campaigns

in the east (Bland 1991a, 1991b). In between, in 240242, Antioch struck three issues

Fig. 28.26 Fig. 28.27

0001341912.INDD 526 9/24/2011 7:08:28 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 527

Fig. 28.28 Fig. 28.29

of tetradrachms (fig. 28.28) and it is likely that a silver coinage struck at Caesarea in

Cappadocia between 239 and 242 (fig. 28.29) should also be linked to military activ-

ity in the east (Bland 1991b).

In fact, the picture we have from Gordians reign is that the provincial silver

coinages from the major mints of Antioch, Caesarea, and Alexandria in Egypt were

used by the state to meet its needs as much as the radiate coins. This becomes even

clearer in the reign of Philip, when not only did Antioch continue to issue large

issues of radiates and even larger issues of tetradrachms but the mint of Rome also

helped out, issuing Antiochene-style tetradrachms with the legend MON VRB

(fig. 28.30), indicating beyond doubt that these had been produced at Rome and

then shipped out to Syria, where they circulated (Baldus 1969). Nor was this new:

under Severus Alexander, the mint of Rome had issued a series of Alexandrian-style

tetradrachms for circulation in Egypt (Burnett and Craddock 1983).

Antioch continued to issue radiates and tetradrachms in the reigns of Trajan

Decius (249251) and Trebonianus Gallus (251253; fig. 28.31), at which point the

tetradrachm production stopped, although radiates continued (along with a few

rare asses). A second mint has also been identified in the east at this time, its prod-

ucts being distinguished by the use of reverse designs that contain two figures

(Carson 1968). However, the coins from the Second Eastern Mint have a circula-

tion pattern identical to the radiates of Antioch, and arguably they should be

regarded as a special issue of the mint of Antioch (fig. 28.32). After the capture of

Valerian, Macrianus and Quietus (260261) issued radiates at Antioch (fig. 28.33),

and after their defeat, the mint continued to strike in the name of Gallienus

(fig. 28.12), although by this time it was actually under the control of the Palmyrene

ruler Odenathus, who chose, however, to continue to recognize Gallienus, just as

Zenobia, his widow and successor, recognized Claudius II and, at first, Aurelian.

Fig. 28.30 Fig. 28.31

0001341912.INDD 527 9/24/2011 7:08:29 PM

528 the roman world

Fig. 28.32 Fig. 28.33

Fig. 28.34 Fig. 28.35

At some point late in Gallienuss sole reign, a new series of coins appears in a

distinctive, local style with reverses bearing the letters SPQR in the exergue

(fig. 28.34). These coins, too, circulate in Syria and eastern Asia and not in the west-

ern part of Asia, but they seem to be from a mint other than Antioch: for the pres-

ent, the location of this mint remains uncertain. Claudius II (268270) also struck a

series of coins with SPQR on the reverse in this distinctive style (fig. 28.35), but then

these are replaced by coins in a completely different style, closer to that of the mint

of Rome, some of which bear the letters M C on the reverse, which has been inter-

preted as Moneta Cyziceni, or mint of Cyzicus (fig. 28.36) (Mairat 2007).

Confusingly coins with SPQR also occur in the new Roman style as well. This

coinage has a different circulation pattern from the local-style SPQR coins, as they

are found predominantly in western Asia Minor and the Balkans, so the attribution

to Cyzicus seems secure.

Moving west, Viminacium in Moesia Superior had struck a large series of

bronze coins signed COL VIM since the reign of Gordian III. It is very likely that the

coinage of the usurper Pacatian, who rebelled against Philip in 248249, was issued

there (Szaivert 1983; Bland and Amandry 1992; fig. 28.37). Rare radiates of Aemilian

(253) in a non-Roman style have also been attributed to Viminacium (fig. 28.38),

and a series of coins issued by Valerian and family for the first four or five years of

his reign may be attributed to that mint, as the circulation pattern of these coins

Fig. 28.36 Fig. 28.37

0001341912.INDD 528 9/24/2011 7:08:30 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 529

Fig. 28.38 Fig. 28.39

supports a Balkan origin for them (fig. 28.39). The mint was closed in 257 or 258

when production was transferred to Gaul.

An issue of radiates from Gallienuss sole reign (260268), with the letters SP or

P II in the field, has sometimes been attributed to Sirmium in Pannonia Inferior, as

the letters have been expanded as Secunda Pannonia or Pannonia II (fig. 28.40).

However, these coins are stylistically very similar to those of Rome and they should

probably be regarded a special issue of the mint of Rome intended perhaps for

Pannonia Inferior.

One of the most prolific mints in the late empire was Siscia (Sisak) in Pannonia

Superior. This mint was opened by Gallienus in about 262, apparently using person-

nel from the mint of Rome, as its earliest issues are stylistically almost indistin-

guishable from those of Rome, although within a few years the coins develop their

own distinctive style. The attribution is not in doubt, however, as there is a reverse

inscribed SISCIA AVG (fig. 28.41).

At the end of Valerians reign in about 259260 a second mint was founded at

Milan (Mediolanum) in the north of Italy. It struck a single issue of coins for

Valerian and then copious issues for Gallienus (fig. 28.42) and his successors. Late in

his reign, in about 268, Gallienuss cavalry commander Aureolus, who was based in

Milan, rebelled against his master and declared for Postumus (fig. 28.43), but after

Gallienuss death Claudius regained control of the mint.

Fig. 28.40 Fig. 28.41

Fig. 28.42 Fig. 28.43

0001341912.INDD 529 9/24/2011 7:08:32 PM

530 the roman world

In 257258 Valerian transferred the mint of Viminacium to Gaul (or Germany),

where presumably coins were needed to meet the needs of Gallienuss campaigns on

the Rhine frontier, and from then on Gaul and Germany was an important center of

coin production for the rest of the Roman period. The identity of the mint, or mints,

in Gaul remains much more problematic. The candidates are Lyon, the capital of

Gallia Lugdunensis, a mint in the first century AD, and there are reformed radiates of

Aurelian signed L, issued shortly after the defeat of Tetricus (fig. 28.44), suggesting

that this city was the main Gallic mint at that time; Cologne (Colonia Claudia Ara

Agrippinensium), capital of Germania Inferior, as a series of radiates from late in

Postumuss reign have the inscription COL CL AGRIP or CCAA (fig. 28.45); and

Trier, which was to become the principal mint in the western empire from the reign

of Diocletian and where, epigraphic evidence indicates, a mint existed earlier

(Drinkwater 1987: 128). It is very hard to untangle exactly which coins were pro-

duced at which mints. We do not know where the mint established by Valerian in

Gaul in about 257 was (Carson 1990: 95 suggests it may have been at Lyon; fig. 28.46).

This mint then became Postumuss principal mint when he declared himself

emperor in 260. The radiates of Postumus signed as coming from Cologne are simi-

lar in style to the coins from Postumuss principal mint (Besly and Bland 1983), but

it is normally assumed that the principal mint was elsewhere, because if Cologne

had been the seat of the Gallic mint since its establishment in 257258, it is hard to

see why it should suddenly start signing its products after it had been in existence

for some 10 years.

Under Postumuss successors, Marius (269), Victorinus (269271), and Tetricus

(271274), scholars since the time of Elmer (Elmer 1941) have distinguished two

mints, one of which worked in two subdivisions, or officinae, and showed the

emperor with a draped and cuirassed bust, and the other worked in a single officina

and showed the emperor with a bust that was cuirassed only (see now Gricourt

Fig. 28.44 Fig. 28.45

Fig. 28.46

0001341912.INDD 530 9/24/2011 7:08:33 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 531

and Hollard 2010). However, there is no difference in the circulation patterns of the

products of these two mints, and Schulte, who has studied the gold coinage

(Schulte 1983), believed that all the aurei of the Gallic Empire were struck at a sin-

gle mint. It is therefore possible to suggest that maybe there was just a single mint

active in the Gallic Empire, albeit one that worked in two separate divisions, one of

which was further subdivided into two officinae. As for where this mint was located,

Lyon, Cologne, and Trier are all possibilities, and some late coins of Postumus

must have been minted at Cologne, but we do know that after Aurelian recovered

Gaul from Tetricus he started to produce his reformed coins at Lyon (Bastien

1976).

Iconography

With a few exceptions, the coinage of this period is not notable for its iconogra-

phy. As the coinage came to be issued in ever greater quantities, inevitably the

standard of design and the quality of production declined, and the designs also

became increasingly banal, with reverses such as PAX AVG (fig. 28.11) or mili-

tary types, such as FIDES EXERCI (fig. 28.7), dominating. Designs alluding to

specific events are rare, which makes them all the more interesting when they

do occur.

Philip Is earliest issues from the mint of Antioch, struck to pay a subsidy to

Shapur (mentioned above) contain the legend PAX FVNDATA CVM PERSIS

(peace established with the Persians; fig. 28.14). In 248, Philip celebrated the eleven

hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Rome with a lavish series of games, and

these are commemorated in coinage in all three metals, bearing the inscription

SAECVLARES AVGG, with designs showing some of the wild animals used in the

games (fig. 28.47).

Philips successor, Trajan Decius, celebrated his origins in Pannonia with the

designs GENIVS EXERCITVS ILLVRICANI (fig. 28.48), PANNONIAE, and

DACIA FELIX. He also struck a series of radiates commemorating his deified

predecessors (Augustus, Vespasian, Titus, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius,

Marcus Aurelius, Commodus (fig. 28.49), Septimius Severus, and Severus

Alexander), perhaps a conscious attempt to claim a link with his more illustrious

namesake.

Fig. 28.47 Fig. 28.48

0001341912.INDD 531 9/24/2011 7:08:34 PM

532 the roman world

Fig. 28.49 Fig. 28.50

But perhaps the most interesting coin designs in this period were issued by

Gallienus at the mint of Rome in the last two years of his reign. This period, when

the technical quality of the coinage was at a low ebb, saw a great flowering of

unusual iconography (see, for example, Abdy 2002b). Gold coins were issued

depicting Gallienus wearing a crown of reeds with the unusual legend GALLIENAE

AVGVSTAE, which has variously been interpreted as a depiction of Gallienus as

the goddess Ceres or alternatively as a hypercorrection of the vocative form

Galliene Auguste (Kent 1973; fig. 28.50). The radiate coinage has a series of ani-

mals commemorating various deities (Apollo, Diana, Jupiter, Liberor Bacchus,

fig. 28.6Neptune, and Sol) with the legend CONS AVG: this issue has been inter-

preted as a ceremonial propitiation at a time of crisis (Weigel 1990). Most unusual,

perhaps, is a late issue of bronze coins that, instead of bearing the emperors por-

trait, have that of the the Genius of the Roman People (GENIVS P R; Yonge

1979). The reverses of these coins all have SC within a laurel wreath; some also add

the inscription INT[roitus] VRB[is] (the entry into Rome; fig. 28.51). Coins that

lack an imperial portrait are extremely rare during the Roman Empire, and these

have in the past been attributed to the interregnum between Aurelian (270275)

and Tacitus (275276). Yonge showed clearly, though, that they date to late in

Gallienuss sole reign, to AD 266, and may have been struck on his return to Rome

from Athens in 266.

The coinage of the Gallic Empire, especially that of Victorinus and Tetricus, is

among the poorest in quality of the Roman period, but the die engravers were still

capable of rising to great heights on special occasions, and the aurei of Postumus

with a three-quarters facing bust are among the finest Roman coins ever produced

(fig. 28.17).

Fig. 28.51

0001341912.INDD 532 9/24/2011 7:08:34 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 533

Until recently, historians depicted the developments in the currency in this

period as one of complete collapse: for example, in 1937 Sutherland noted of the

coinage during this period: Since prices everywhere must have soared . . . it is not

hard to imagine the widespread economic ruin that must have prevailed (1937:

49). It is certainly true that the quality of the silver coinage did decline dramati-

cally during this period, probably because of the drying up of new supplies of

bullion. However, an operation that was capable of producing tens of millions of

coins each week, as we saw was the case under Victorinus, must have been a

sophisticated one, and the effect of these changes, unintended though it may

have been, was to spread coin use much more widely across the whole of the

empire.

Notes

1. For the often difficult chronology of this period see Kienast 1990 and Peachin 1990.

2. However, to put this figure in context, Gordians second series of radiates from

Antioch, minted in AD 242244, was struck from an estimated 1,8493,000 obverse dies,

which could suggest that 5590 million coins were struck (see note 4). Seen in this light,

Philips payment to Shapur looks very small.

3. In fact, the rather scanty evidence suggests that he reigned from late autumn 269 to

late summer 271 (Knig 1981: 143144), rather less than two years, so the estimates that

follow are conservative.

4. Estimating the size of the coinage from counting the number of obverse dies used

has proved to be very controversial. Kinns 1983, studying the silver coinage of the

Amphictions of Delphi, for which independent epigraphic evidence existed for the amount

of bullion minted, estimated that the obverse dies could have produced between 23,000

and 47,000 coins, while Mate (1969), using mint figures from thirteenth- and fourteenth-

century England, showed that the obverse dies used for the silver pennies of Edward I and

II between 1281 and 1327 had an average production of between 5,000 and 74,000. However,

Buttrey (1993, 1994) has condemned attempts to estimate the size of the coinage in this way,

on the grounds that there are so many variables involved of which we today can have no

knowledge. In my view, there is a value in such calculations, providing that the die sample

is large enough and that it is made clear that the figures obtained in this way can only be

indicative (see Howgego 1995: 3133).

5. For comparison, Gordian IIIs first series of radiates from Antioch (238239) was

struck by between 611 and 753 obverse dies and the second series (242244) by 1,8493,000

obverse dies. So they first series could have consisted of 1823 million coins and the second

of 5590 million coins.

6. For example, the highest number of English silver pennies struck during any year

between 1281 and 1327 was 31 million (Mate 1969).

7. The data is taken from Brenot and Loriot (1992), who brought together a series of

regional studies of single finds of gold coins (from Julius Caesars issue of 46 BC to AD

491) from across the western Roman empire (Spain, Gaul, Germany, Britain, Raetia,

Noricum, Pannonia, and northern Italy), a corpus of 2,800 examples.

0001341912.INDD 533 9/24/2011 7:08:35 PM

534 the roman world

Key to Illustrations

Fig. 28.1. Gordian III; radiate; Rome; rev.: IOVI CONSERVATORI, RIC 2; 1937-4-4-221

(Dorchester hoard).

Fig. 28.2. Gordian III; denarius; Rome; rev.: VENVS VICTRIX, RIC 125; PCR 778.

Fig. 28.3. Philip II Caesar; quinarius; Rome; rev.: PIETAS AVGG, RIC -; 1977-5-4-2.

Fig. 28.4. Trajan Decius; radiate; Rome; rev.: ABVNDANTIA AVG, RIC 10(b), overstruck

on denarius of Severus Alexander; PCR 805A.

Fig. 28.5. Valerian; radiate; Rome; rev.: APOLINI PROPVG, RIC 74; PCR 837.

Fig. 28.6. Gallienus sole reign; radiate; Rome; rev.: LIBERO P CONS AVG, RIC 230; PCR

876.

Fig. 28.7. Claudius II; radiate; Rome; rev.: FIDES EXERCI XI, RIC 36 var.; 1985-7-44-20

(Wickham Market hoard).

Fig. 28.8. Postumus; radiate; Principal mint; rev.: HERC DEVS ONIENSI, RIC 66; PCR

911.

Fig. 28.9. Laelian; radiate, Mint II; rev.: VICTORIA AVG, RIC 9; PCR 924.

Fig. 28.10. Victorinus; radiate; Mint I; rev.: INVICTVS, RIC 114; 1964-7-1-174 (Kirmington

hoard).

Fig. 28.11. Tetricus I; radiate; Mint I; rev.: PAX AVG, RIC 100; 1964-7-1-215 (Kirmington

hoard).

Fig. 28.12. Gallienus sole; radiate; Antioch; rev.: SOLI INVICTO PXV, RIC 611; PCR 882.

Fig. 28.13. Aurelian and Vabalathus; radiate; Antioch; Officina , RIC 381; PCR 988.

Fig. 28.14. Philip I; radiate; Antioch; rev: PAX FVNDATA CVM PERSIS, RIC 69; PCR 801.

Fig. 28.15. Trebonianus Gallus; gold radiate; Rome; rev.: FELICITAS PVBLICA, RIC 8; PCR

821.

Fig. 28.16. Gallienus sole; aureus; Rome; rev.: VBIQVE PAX, 1.07g, RIC 73; 1862-4-15-2.

Fig. 28.17. Postumus; aureus; Principal mint; rev.: INDVLG PIA POSTVMI AVG, RIC 277;

PCR 914.

Fig. 28.18. Gallienus (joint reign); sestertius; Rome; rev.: CONCORDIA EXERCIT S C, RIC

209; R 4151.

Fig. 28.19. Gallienus; as; Antioch; rev.: AEQVITAS AVGG, RIC -; 1983-7-2-2.

Fig. 28.20. Trajan Decius; double sestertius; Rome; rev.: FELICITAS SAECVLI S C, RIC

115(a); PCR 806.

Fig. 28.21. Trajan Decius; semis; Rome; rev.: S C, RIC 128; PCR 807.

Fig. 28.22. Postumus; sestertius; Principal mint (?); large: rev.: RESTITVTOR GALLIAE S

C, 31.91 g, RIC 157; PCR 905.

Fig. 28.23. Postumus; sestertius; Principal mint (?); very small: rev.: DIANAE LVCIFERAE

RIC -, 6.06 g; 1906-11-3-2831.

Fig. 28.24. Plated denarius of Severus Alexander; 2000-6-21-1.

Fig. 28.25. Barbarous radiate copying coin of Tetricus; 1938-7-3-206 (from Richborough).

Fig. 28.26. Gordian III; radiate; Antioch; 1st series, rev.: PM TRP II COS PP, Adventus type,

RIC -; 1982-1-2-1.

Fig. 28.27. Gordian III; radiate; Antioch; 2nd series, rev.: SAECVLI FELICITAS, RIC 216(e);

1924-1-7-187 (Plevna hoard).

Fig. 28.28. Gordian III; tetradrachm; Antioch; 2nd consulship, AD 242, BMC -; 1985-6-11-1.

Fig. 28.29. Gordian III; tridrachm; Caesarea; rev.: T (240-1); 1979-1-1-1152 (von Aulock).

Fig. 28.30. Philip I; tetradrachm; minted at Rome in style of Antioch; rev.: HMAPX

OYCIAC S C MON VRB; 1948-6-2-6.

0001341912.INDD 534 9/24/2011 7:08:35 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 535

Fig. 28.31. Trebonianus Gallus; tetradrachm; Antioch; rev.: HMAPX OYCIAC S C;

1948-6-2-18.

Fig. 28.32. Gallienus (joint reign); radiate; 2nd eastern mint; rev.: VICTORIA GERMAN,

RIC 452; 1961-8-5-220.

Fig. 28.33. Macrianus; radiate; Antioch; rev.: ROMAE AETERNAE, RIC 11; PCR 884.

Fig. 28.34. Gallienus sole; radiate; SPQR mint; rev.: MINERVAE AVG SPQR, RIC 651 var.;

1988-8-4-1.

Fig. 28.35. Claudius II; radiate; SPQR mint; rev.: ROMAE AETERNAE SPQR, RIC 241;

1988-6-1-4.

Fig. 28.36. Claudius II; radiate; Cyzicus; rev.: VIRTVTI AVGVSTI M C, RIC -; 1973-5-8-13.

Fig. 28.37. Pacatian; radiate; Viminacium; rev.: FORTVNA REDVX, RIC 4; PCR 802.

Fig. 28.38. Aemilian; radiate; Viminacium; rev.: VIRTVS AVG, RIC 26; 1950-11-1-1.

Fig. 28.39. Valerian; radiate; Viminacium; rev.: VICTORIA GERMANICA, RIC 263; R0792.

Fig. 28.40. Gallienus sole reign; radiate; Sirmium; rev.: PROVID AVG P II, RIC 580;

1844-4-25-2005.

Fig. 28.41. Gallienus sole reign; radiate; Siscia; rev.: SISCIA AVG, RIC 582; 1961-8-5-972.

Fig. 28.42. Gallienus sole reign; radiate; Milan; rev.: LEG X GEM, RIC 357; R0811.

Fig. 28.43. Postumus; radiate; Milan; rev.: FIDES EQVIT, RIC 378; PCR 922.

Fig. 28.44. Aurelian; radiate; Lyon; rev.: PACATOR ORBIS A L, RIC 6; 1962-12-12-1

(Gloucester hoard).

Fig. 28.45. Postumus; radiate; Cologne; rev.: COL CL AGRIP COS IIII, RIC 286; PCR 921.

Fig. 28.46. Gallienus (joint reign); radiate; mint of Gaul; rev.: RESTITVTOR GALLIAR,

RIC 31; 1937-5-9-1569 (Dorchester hoard).

Fig. 28.47. Philip; radiate; Rome; rev.: SAECVLARES AVGG, RIC 12; PCR 795.

Fig. 28.48. Trajan Decius; radiate; Rome; rev.: GENIVS EXERCITVS ILLVRICIANI, RIC

4(b); 1924-1-7-673 (Plevna hoard).

Fig. 28.49. Trajan Decius; radiate; Rome; rev.: DIVO COMMODO, RIC 96; PCR 819.

Fig. 28.50. Gallienus sole; aureus; Rome; rev.: GALLIENAE AVGVSTAE, RIC 74; PCR 875.

Fig. 28.51. Anonymous (GENIVS PR); sestertius; Rome; rev.: INT VRB S C, RIC 2; PCR

874.

Fig. 28.52. Quantity of silver minted, AD 238282 (after Depeyrot and Hollard 1987).

Fig. 28.53. The coin loss pattern of a typical British site (from Reece 1995).

Fig. 28.54. Stray finds of gold coins, 46 BCAD 491.

Bibliography

Abdy, R. (2002a). Romano-British Coin Hoards. Princes Risborough.

. (2002b). A new coin type of Gallienus found in Hertfordshire. NC 162:

346350.

Baldus, H.-R. (1969). MON(eta) URB(is)-ANTIOXIA. Rom und Antiochia als Prgesttten

syrischer Tetradrachmen des Philippus Arabs. Frankfurt.

Bastien, P. (1967). Le monnayage de bronze de Postume. Wetteren, Switzerland.

. (1976). Le monnayage de latelier de Lyon, 1. De la rouverture de latelier par

Aurlien la mort de Carin (fin 274mi 285). Wetteren, Switzerland.

Besly, E. M., and R. F. Bland. (1983). The Cunetio Treasure. London.

0001341912.INDD 535 9/24/2011 7:08:36 PM

536 the roman world

Bland, R. F. (1991a). The Coinage of Gordian III from the Mints of Antioch and Caesarea.

Ph.D. diss., University of London.

. (1991b). The last coinage of Caesarea in Cappadocia. In Ermanno A Arslan Studia

Dicata I. Glaux 7. Milan: 213258.

. (1996). The development of gold and silver denominations, AD 193253. In King

and Wigg: 63100.

Bland, R. F., and M. Amandry. (1992). Monnaies romaines rares du mdaillier du Muse

Saint-Remi. BSFN 47(6): 333339.

Boon, G. C. (1998). Counterfeit coins in Roman Britain. In Casey and Reece: 102188.

Burnett, A. (1987). Coinage in the Roman World. London.

Burnett, A. M., and P. Craddock. (1983). Rome and Alexandria: The minting of Egyptian

tetradrachms under Severus Alexander. ANSMN 28: 109118.

Buttrey, T. V. (1993). Calculating ancient coin production: Facts and fantasies. NC 153:

335351.

. (1994). Calculating ancient coin production II: Why it cannot be done. NC 154:

341352.

Callu, J.-P. (1969). La politique montaire des empereurs romains de 238 311. Paris.

Carson, R. A. G. (1968). The Hma hoard and the eastern mints of Valerian and

Gallienus. Berytus 17: 123142.

. (1990). Coins of the Roman Empire. London.

Carson, R. A. G., and C. M. Kraay, eds. (1978). Scripta Nummaria Romana. Essays Presented

to Humphrey Sutherland. London.

Casey, P. J., and R. Reece, eds. (1988). Coins and the Archaeologist. 2nd ed. London.

Cope, L. (1974). The Metallurgical Development of the Roman Imperial Coinage during

the First Five Centuries AD. Ph.D. diss., University of Liverpool.

Cope, L., et al. (1997). Metal Analyses of Roman Coins Minted under the Empire. British

Museum Occasional Paper 120. London.

Depeyrot, G., and D. Hollard. (1987). Pnurie dargent-mtal et crise montaire au IIIe

sicle aprs J-C. Histoire et Msure 2(1): 5785.

Drinkwater, J. F. (1987). The Gallic Empire. Historia Einzelschriften 52. Stuttgart.

Duncan-Jones, R. (1994). Money and Government in the Roman Empire. Cambridge.

Elks, K. J. J. (1972). The denarii of Gordian III. NC 7 12: 309310.

Elmer, G. (1941). Die Mnzprgung der gallischen Kaiser in Kln, Trier und Mailand.

Bonner Jahrbcher 146: 1106.

Frank, T. (1940). An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome. Vol. 5. Text and Translation of

Diocletians Edict by E. R. Graser. Baltimore.

Gilljam, H. H. (1982). Antoniniani und Aurei des Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus, Gegenkaiser des

Postumus. Cologne.

. (1986). 269. Laelianus. Ergnzungen zur Materialsammlung. Verwendung seiner

Reversstempel unter Marius. Cologne.

Gbl, R. (2000). Die Mnzprgng des Kaiser Valerianus I./Gallienus/Saloninus (253/268).

Regalianus (260) und Macrianus/Quietus (260/262). Moneta Imperii Romani 38.

Vienna.

Gricourt, D., and Hollard, D. (2010). Les productions monetaires de Postume en 268269

et celles de Lelien (269). Nouvelles propositions. NC 170: 129204.

Harl, K. W. (1996). Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 BC to AD 700. Baltimore.

Howgego, C. J. (1995). Ancient History from Coins. London.

. (1996). The circulation of silver coins, models of the Roman economy, and crisis

in the third century AD: Some numismatic evidence. In King and Wigg: 219236.

0001341912.INDD 536 9/24/2011 7:08:36 PM

from gordian iii to the gallic empire (ad 238274) 537

Jones, G. D. B. (1980). The Roman mines at Riotinto. JRS 70: 146165.

Kent, J. P. C. (1973). Gallienae Augustae. NC 7 13: 6468.

Kienast, D. (1990). Rmische Kaisertabelle. Darmstadt.

King, C. E. (1978). Denarii and quinarii, AD 253295. In Carson and Kraay: 75104.

. (2007). Roman Quinarii from the Republic to Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. London.

King, C. E., and D. G. Wigg, eds. (1996). Coin Finds and Coin Use in the Roman World.

Studien zu Fundmnzen der Antike 10. Berlin.

Kinns, P. (1983). The Amphictionic coinage reconsidered. NC 143: 122.

Knig, I. (1981). Die gallischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus, Vestigia 31. Munich.

Mairat, J. (2007). Louverture de latelier imprial de Cyzique sous le rgne de Claude II le

Gothique. RN 163: 175-196.

Mate, M. (1969). Coin dies under Edward I and II. NC 7 17: 207218.

Millar, F. (1993). The Roman Near East 31 BCAD 337. Cambridge, Mass.

Morrisson, C., et al. (1985). Lor monnay I. Purification et altrations de Rome Byzance.

Cahiers Ernest-Babelon 2. Paris.

Mouchmov, N. A. (1934). Le trsor numismatique de Rka-Devnia. Sofia.

Peachin, M. (1990). Roman Imperial Titulature and Chronology, AD 235284. Amsterdam.

Price, M., A. Burnett, and R. Bland, eds. (1993). Essays in Honour of Robert Carson and

Kenneth Jenkins. London.

Reece, R. (1991). Roman Coins from 140 Sites in Britain. Cirencester.

. (1995). Site finds in Roman Britain. Britannia 26: 179206.

. (2002). The Coinage of Roman Britain. Stroud, England.

. (2003). Roman Coins and Archaeology. Collected Papers. Wetteren, Switzerland.

Schulte, B. (1983). Die Goldprgung der gallischen Kaiser von Postumus bis Tetricus. Typos 4.

Aarau.

Sutherland, C. H. V. (1937). Coinage and Currency in Roman Britain. Oxford.

Szaivert, W. (1983). Der Beginn der Antonianprgung in Viminacium. Litterae

Numismaticae Vindobonenses 2: 6167.

Tyler, P. (1975). The Persian Wars of the 3rd Century AD and Roman Imperial Monetary

Policy, AD 25368. Historia Einzelschriften 23. Wiesbaden.

Walker, D. R. (1978). The Metrology of the Roman Silver Coinage. Vol. 3. British

Archaeological Reports Supplementary Series 40. Oxford.

Weigel, R. D. (1990). Gallienus Animal Series coins and Roman religion. NC 150: 135144.

Yonge, D. (1979). The So-called interregnum coinage. NC 7 19: 4860.

0001341912.INDD 537 9/24/2011 7:08:36 PM

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- From Gordian III To The Gallic Empire ADDocumento24 pagineFrom Gordian III To The Gallic Empire ADGiacomo BondarelliNessuna valutazione finora

- Treasures of DecebalusDocumento11 pagineTreasures of DecebalusGürkan ErginNessuna valutazione finora

- E111 135Documento25 pagineE111 135gladysNessuna valutazione finora

- Medallions of The Roman Empire An IntrodDocumento19 pagineMedallions of The Roman Empire An IntrodMichael KorrNessuna valutazione finora

- Monetarna Reforma Cara AurelijanaDocumento12 pagineMonetarna Reforma Cara AurelijanaDanijel KasunićNessuna valutazione finora

- The Silver Coinage of Roman Syria Under The Julio-Claudian EmperorsDocumento20 pagineThe Silver Coinage of Roman Syria Under The Julio-Claudian Emperorstarek elagamyNessuna valutazione finora

- BACHARACH (1971) Circassian Monetary Policy. SilverDocumento9 pagineBACHARACH (1971) Circassian Monetary Policy. Silverpax_romana870Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2009 Dodd 1 PHDDocumento10 pagine2009 Dodd 1 PHDSafaa SaiedNessuna valutazione finora

- Value of Gold in Ancient EgyptDocumento8 pagineValue of Gold in Ancient EgyptDaniel González EricesNessuna valutazione finora

- Did The So-Called Thraco-Macedonian Sta PDFDocumento30 pagineDid The So-Called Thraco-Macedonian Sta PDFplatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Sutherland 1955Documento4 pagineSutherland 1955Santiago RobledoNessuna valutazione finora

- Three Seleucid Notes / Brian Kritt, Oliver D. Hoover and Arthur HoughtonDocumento31 pagineThree Seleucid Notes / Brian Kritt, Oliver D. Hoover and Arthur HoughtonDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Late Roman Coin Hoards in The West, Trash or Treasure RBN 2007Documento15 pagineLate Roman Coin Hoards in The West, Trash or Treasure RBN 2007tkropffNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of The Chemical Composition of Roman Silver Coinage, A.D. 196-197Documento21 pagineA Study of The Chemical Composition of Roman Silver Coinage, A.D. 196-197Eesha Sen ChoudhuryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Weight of Graeco Bactrian KalchusDocumento4 pagineThe Weight of Graeco Bactrian KalchusSajad AmiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Toynbee 1944Documento11 pagineToynbee 1944Aliye ErolNessuna valutazione finora

- Caracallas PathDocumento20 pagineCaracallas PathKreisel 1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Historical References On Coins of The Roman Empire, From Augustus To Gallienus / by Edward A. SydenhamDocumento159 pagineHistorical References On Coins of The Roman Empire, From Augustus To Gallienus / by Edward A. SydenhamDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (2)

- And Old Babylonian Periods. (Mcdonald Institute: Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesDocumento3 pagineAnd Old Babylonian Periods. (Mcdonald Institute: Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesSajad AmiriNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gold Coinage of Alexander's LifetimeDocumento41 pagineThe Gold Coinage of Alexander's LifetimeplatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Byz CoinsDocumento67 pagineByz CoinsLaurentiu RaduNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesDocumento2 pagineBulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesSajad AmiriNessuna valutazione finora

- The Byzantine Eagle Countermark: Creating A Pseudo-Consular Coinage Under The Heraclii?Documento19 pagineThe Byzantine Eagle Countermark: Creating A Pseudo-Consular Coinage Under The Heraclii?Alri MochtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Carlson-2007-International Journal of Nautical ArchaeologyDocumento8 pagineCarlson-2007-International Journal of Nautical ArchaeologyJoaquim BlayNessuna valutazione finora

- Coinc Ollectors ManualDocumento404 pagineCoinc Ollectors ManualJustin100% (3)

- Notes On The Imperial Persian Coinage / G.F. HillDocumento17 pagineNotes On The Imperial Persian Coinage / G.F. HillDigital Library Numis (DLN)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Birth of Coins PDFDocumento43 pagineBirth of Coins PDFnaglaa100% (1)

- Reinvestigating The Second Dynasty at SaDocumento98 pagineReinvestigating The Second Dynasty at Saarthur farrowNessuna valutazione finora

- Miscellanea.: Seutonius Related Character of TheDocumento28 pagineMiscellanea.: Seutonius Related Character of The12chainsNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of The Chemical Composition of Roman Silver Coinage, AD 196-197 / Kevin Butcher and Matthew Ponting With A Contrib. by Graham ChandlerDocumento24 pagineA Study of The Chemical Composition of Roman Silver Coinage, AD 196-197 / Kevin Butcher and Matthew Ponting With A Contrib. by Graham ChandlerDigital Library Numis (DLN)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sardis Coinage 1973-2013 Ramage CahillDocumento352 pagineSardis Coinage 1973-2013 Ramage CahillMatthew LubinNessuna valutazione finora

- (Guides To The Coinage of The Ancient World) Clare Rowan - From Caesar To Augustus (C. 49 BC-AD 14) - Using Coins As Sources-Cambridge University Press (2018)Documento256 pagine(Guides To The Coinage of The Ancient World) Clare Rowan - From Caesar To Augustus (C. 49 BC-AD 14) - Using Coins As Sources-Cambridge University Press (2018)Shreeya YumnamNessuna valutazione finora

- Astronomical Reflexes in Ancient CoinsDocumento30 pagineAstronomical Reflexes in Ancient CoinsAnitaVasilkovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Calligraphers Created Dies For Islamic Coinage: MiscellaneaDocumento20 pagineCalligraphers Created Dies For Islamic Coinage: Miscellanea12chainsNessuna valutazione finora

- ANS BedoukianDocumento807 pagineANS BedoukianVasja SlanicNessuna valutazione finora

- Johnston, A. E. M. - The Earliest Preserved Greek Map. A New Ionian Coin Type - JHS, 87 - 1967!86!94Documento13 pagineJohnston, A. E. M. - The Earliest Preserved Greek Map. A New Ionian Coin Type - JHS, 87 - 1967!86!94the gatheringNessuna valutazione finora

- The Tetrarchic Image: Oxfordjournalof ArchaeologyDocumento15 pagineThe Tetrarchic Image: Oxfordjournalof ArchaeologyChristopher DixonNessuna valutazione finora

- Sydenham-The Roman Monetary System Part 1. 1919Documento40 pagineSydenham-The Roman Monetary System Part 1. 1919Giandomenico PonticelliNessuna valutazione finora

- Preroman and Roman Coinage in North Eastern Italy (II-I Cent. B.C.)Documento9 paginePreroman and Roman Coinage in North Eastern Italy (II-I Cent. B.C.)andrea keberNessuna valutazione finora

- Milne - Alexandrian CoinsDocumento13 pagineMilne - Alexandrian CoinsMarly ShibataNessuna valutazione finora

- Roman Provincial Coinage PT 1Documento15 pagineRoman Provincial Coinage PT 1mp190Nessuna valutazione finora

- CNG McAlee Coins of Roman Antioch Supplement 1 2010Documento32 pagineCNG McAlee Coins of Roman Antioch Supplement 1 2010Артур ДегтярёвNessuna valutazione finora

- TekstDocumento13 pagineTekstChristopher DixonNessuna valutazione finora

- Votive Coins in Delian Inscriptions / Percy GardnerDocumento5 pagineVotive Coins in Delian Inscriptions / Percy GardnerDigital Library Numis (DLN)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dmitriev - Good Emperors and Emperors of The Third CenturyDocumento15 pagineDmitriev - Good Emperors and Emperors of The Third CenturyEleonora MuroniNessuna valutazione finora

- Middle Minoan Objects in The Near East: Crete (1970) 187Documento9 pagineMiddle Minoan Objects in The Near East: Crete (1970) 187Angelo_ColonnaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Seleucid Mint of Antioch / by Edward T. NewellDocumento179 pagineThe Seleucid Mint of Antioch / by Edward T. NewellDigital Library Numis (DLN)0% (1)

- Milne - Currency Ptolemaic Egypt PDFDocumento9 pagineMilne - Currency Ptolemaic Egypt PDFMariaFrankNessuna valutazione finora

- Ships in Ancient RomeDocumento15 pagineShips in Ancient RomejtabNessuna valutazione finora

- The First Aegean Swords and Their AncestryDocumento20 pagineThe First Aegean Swords and Their Ancestryaoransay100% (1)

- Adelson The Bronze AlloysDocumento20 pagineAdelson The Bronze AlloysLeandro rimoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Royal Numismatic Society The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-)Documento8 pagineRoyal Numismatic Society The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-)naglaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Late Roman and Byzantine Silver CoinageDocumento24 pagineLate Roman and Byzantine Silver CoinageFrancisco Javier Ortola SalasNessuna valutazione finora

- GuySanders PDFDocumento5 pagineGuySanders PDFЈелена Ј.Nessuna valutazione finora

- The House of Augustus: A Historical Detective StoryDa EverandThe House of Augustus: A Historical Detective StoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Coins of The Kushan EmpireDocumento15 pagineCoins of The Kushan EmpireDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- A Cypriot Coin of Richard I Lion-HeartDocumento6 pagineA Cypriot Coin of Richard I Lion-HeartDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Artisanal Production in Byzantine Thessaloniki (4th-15th Century)Documento28 pagineArtisanal Production in Byzantine Thessaloniki (4th-15th Century)Dimitris Bofilis100% (1)

- Some More Barbaric Coins - of The Counts of EdessaDocumento2 pagineSome More Barbaric Coins - of The Counts of EdessaDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Arabian Nike - Imitating Macedonian Gold Coins On The Arabian Peninsula (Some Ideas For A Forthcoming Article) 2014 PDFDocumento5 pagineArabian Nike - Imitating Macedonian Gold Coins On The Arabian Peninsula (Some Ideas For A Forthcoming Article) 2014 PDFDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Arsclassicalcoin The M.L. Collection of Coins of Magna Graecia and SicilyDocumento59 pagineArsclassicalcoin The M.L. Collection of Coins of Magna Graecia and SicilyDimitris Bofilis100% (1)

- Victory, Torcs and Iconology in Rome and BritainDocumento24 pagineVictory, Torcs and Iconology in Rome and BritainDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Kolbe & Fanning Sale147Documento80 pagineKolbe & Fanning Sale147Dimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- A New Antoninianus in The Name of Saloninus As Augustus in - The Numismatic Chronicle 175-, London, 2015Documento8 pagineA New Antoninianus in The Name of Saloninus As Augustus in - The Numismatic Chronicle 175-, London, 2015Dimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- A History of Ancient Coinage, 700-300 B.C. 1918 PDFDocumento510 pagineA History of Ancient Coinage, 700-300 B.C. 1918 PDFDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient and Early Medieval Coins From Cornwall & Scilly PDFDocumento326 pagineAncient and Early Medieval Coins From Cornwall & Scilly PDFDimitris Bofilis100% (1)

- Sincona 12Documento528 pagineSincona 12Dimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- A Hoard of Tetradrachms From The First MDocumento26 pagineA Hoard of Tetradrachms From The First MDimitris BofilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Declaration Form enDocumento2 pagineDeclaration Form enMartina MartynaNessuna valutazione finora

- Flipping Markets: PDF Cheat SheetDocumento59 pagineFlipping Markets: PDF Cheat SheetAsh Sam100% (8)

- Sale Invoice32011 06-03-2020Documento1 paginaSale Invoice32011 06-03-2020Ione TheNessuna valutazione finora

- Paluan NG Palayok-Kung Saan: PiringDocumento3 paginePaluan NG Palayok-Kung Saan: PiringJuliet C. Clemente0% (2)

- Astro Grabbies - Uranus Pluto - and The Money GameDocumento7 pagineAstro Grabbies - Uranus Pluto - and The Money GameMariaa RodriguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2-Foreign Trade Policies-MCQsDocumento10 pagineChapter 2-Foreign Trade Policies-MCQsAlishba NadeemNessuna valutazione finora

- BANGLADESH BANK GUIDELINES FOR FOREIGN EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS Vol 1Documento137 pagineBANGLADESH BANK GUIDELINES FOR FOREIGN EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS Vol 1Osman Goni100% (6)

- Rules For Forex TradingDocumento22 pagineRules For Forex Tradinglever70Nessuna valutazione finora

- Class Notes International FinancesDocumento9 pagineClass Notes International FinancesMariabelen DoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- International Finance PresentationDocumento29 pagineInternational Finance PresentationY.h. TariqNessuna valutazione finora

- D4Documento6 pagineD4crap talkNessuna valutazione finora

- Revolut - Kopia - Kopia - Kopia - Kopia - KopiaDocumento13 pagineRevolut - Kopia - Kopia - Kopia - Kopia - Kopialuka26Nessuna valutazione finora

- IGCSE MCQ ChecklistDocumento8 pagineIGCSE MCQ ChecklistDhrisha GadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise: "Consumer & Business Market Comparative Chart"Documento4 pagineExercise: "Consumer & Business Market Comparative Chart"Orlando HernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- Le Bob ArtichautDocumento1 paginaLe Bob ArtichautRodissauro 1Nessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 7 - Solman CONSOLIDATED FS PART 4 - ACCTG FOR BUS. COMBINATIONSDocumento20 pagineCHAPTER 7 - Solman CONSOLIDATED FS PART 4 - ACCTG FOR BUS. COMBINATIONSJeeramel TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Cetking MBA CET 2019 Paper by DTE PDF MBA MMS PDFDocumento24 pagineCetking MBA CET 2019 Paper by DTE PDF MBA MMS PDFavinash singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary World New Generation CurrencyDocumento7 pagineContemporary World New Generation CurrencySoojoo HongNessuna valutazione finora

- Change in Polarity by Saif ThobaniDocumento19 pagineChange in Polarity by Saif Thobanilala lajpat raiNessuna valutazione finora

- Drven Roll 530 - 4200 Steel Rubber CoatedDocumento1 paginaDrven Roll 530 - 4200 Steel Rubber CoatedJulian DelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- ERP22006Documento1 paginaERP22006Ady Surya LesmanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mpanda DayDocumento2 pagineMpanda DayKANDONGA FARAJANessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresDocumento2 pagineSummary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresFreed DragsNessuna valutazione finora

- Evp6310009992783 - 2020 01 01 - 2021 09 16Documento184 pagineEvp6310009992783 - 2020 01 01 - 2021 09 16tunisiehyperNessuna valutazione finora

- CRT Test 5 - Qa Va (CTS) - 131751 PDFDocumento38 pagineCRT Test 5 - Qa Va (CTS) - 131751 PDFPraveen AndraNessuna valutazione finora

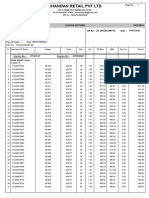

- Chandan Retail PVT LTD GRDocumento2 pagineChandan Retail PVT LTD GRSontu Esperanza FreundNessuna valutazione finora

- 66 Banking Terms For Competitive Exams PDFDocumento12 pagine66 Banking Terms For Competitive Exams PDFasdhahdahsdjhNessuna valutazione finora

- Cash and Cash Equivalents - MidtermDocumento9 pagineCash and Cash Equivalents - MidtermDan RyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Assemani 4 IlischDocumento25 pagineAssemani 4 IlischnuruddevlebelekgaziNessuna valutazione finora

- April Part 2 PDFDocumento11 pagineApril Part 2 PDFAshar khanNessuna valutazione finora