Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cambridge University Press

Caricato da

Kairos QueridoDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cambridge University Press

Caricato da

Kairos QueridoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cycles of Class Struggle and the Making of the Working Class in Argentina, 1890-1920

Author(s): Ronaldo Munck

Source: Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (May, 1987), pp. 19-39

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/156900 .

Accessed: 26/09/2013 13:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of

Latin American Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

J. Lat. Amer. Stud. 19, 19-39 Printed in Great Britain I9

Cycles of class struggle and the making of

the working class in Argentina, 1890-I920

by RONALDO MUNCK

There is currently a renewed interest in the relationship between economic

fluctations and strike movements which refers back to an article by Eric

Hobsbawm' and an even earlier polemical piece by Leon Trotsky.2 This

article offers a contribution to the growing literature, focusing, unlike

most other studies, on a Third World country. It also reflects the increasing

influence of social history in Latin American research on the making of

the working class.

The historical account which follows is framed by a number of

hypotheses derived from the above-mentioned literature:

(i) 'The making of the working class is a fact of political and cultural,

as much as economic, history' (E. P. Thompson).3

(2) 'Long-term depression factors ... helped to accumulate inflammable

material rather than to set it alight' (E. Hobsbawm).4

(3) 'The impetus to the strike wave was the upturn in the economic

conjuncture with a simultaneous rise in the cost of living' (L.

Trotsky).5

(4) 'Workers' militancy depends on two conflicting factors: achieve-

ments and frustration' (E. Screpanti).6

Eric Hobsbawm, 'Economic Fluctuations and some Social Movement', LabouringMen

(London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984).

2 Leon

Trotsky, 'The "Third Period" of the Comintern's Errors', Writings of Leon

Trotsky (New York, Pathfinder Press, I930).

3 E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London, Penguin, I970),

p. 213.

4 Eric

Hobsbawm, op. cit., p. I41.

5 Leon

Trotsky, op. cit., p. 45.

6 Ernesto

Screpanti, 'Long Economic Cycles and Recurring Proletarian Insurgencies',

Review, vol. VII, no. 2 (winter, I984), pp. 509-48.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 Ronaldo Munck

(5) 'With each upturn of a long wave come not only new machines and

rising prices, but the recreation of the working class and much of

the social environment' (J. Cronin).7

These, in brief, are the main ideas which the following account is designed

to illuminate through a case study of Argentina between I890 and i920.

I. Theformativeperiod

From the 850osonwards capital strengthened its economic and political

domination over the territory of Argentina, which had gained its inde-

pendence from Spain in 181 0. A long period of civil wars concluded with

the battle of Caseros in 852 and the adoption of a national constitution

the following year. This political-military process coincided with the

gradual incorporation of the fertile pampa region into the international

circuit of capital accumulation. Argentina was primarily an agricultural

country: the I853 municipal census for Buenos Aires indicated the

presence of 700 workshops and Ioo 'factories' employing some 2,000

workers. During the i88os there was a significant increase in the level of

industrialisation: Buenos Aires could now boast a dozen meat-packing

plants employing nearly 8,000 people and 7 flour mills with 500 workers.

Yet there were on average only ten workers per industrial establishment,

which testifies to the semi-artisanal level of production at this period. A

further characteristic of early industry was the predominant role of

immigrant enterprise and labour: the i887 census found that 92% of

industrial workshops and factories were owned by foreigners, and that

84 % of the workers were immigrants. Between I 887 and I895 the number

of industrial establishments rose from 6, 28 to 8,439 and the number of

wage earners doubled. The I88os had brought to power an organised

section of the ruling classes which was to launch a coherent capitalist

growth project and lead to Argentina's 'golden era' between i890 and

1930.

If capital produces the labour-power it requires, then the working class

is not simply a passive element in the machine of capital accumulation.

In 857, the Buenos Aires printworkers formed the first recorded mutual

aid society, the SociedadTipograficaBonaerense.By I876 the printworkers

had formed the first genuine trade union, followed by the bakers,

carpenters and other trades. In 1887 the railworkers' union La Fraternidad

became the first national organisation. Strike statistics for this period are

7 James Cronin, 'Stages, Cycles and Insurgencies:The Economics of Unrest', in T. K.

Hopkins and I. Wallerstein(eds.), The PoliticalEconomyof the WorldSystem,vol. III

(California, Sage, I980), p. I2.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Struggle in Argentina, I890-I920 2

unreliable but Julio Godio has estimated that some 48 strikes took place

during the i88os, of which an equal number were won and lost by the

workers.8 Most of these strikes occurred in the capital city, Buenos Aires,

and they were mainly concerned with wage demands. The i88os saw the

beginning of a fundamental shift from artisan labour to manufacturing.

Unlike the worker-artisans in the metal or textile workshops, the workers

in the meat-packing plants were mainly native born. The working class

of Argentina was thus taking shape in the melting pot of the class struggle,

a permanent feature from I890. On the one hand, were the descendants

of the gauchosand the internal migration following the collapse of the

provincial rebellions in the i88os; on the other, the overseas migrants,

many of whom, such as those who fled the collapse of the Paris Commune

of 1871, brought with them the political traditions of socialism and

anarchism. At first the overseas immigrants saw real prospects of upward

social mobility, but these hopes were to be dashed in the I89os.

II. Economicdepressionand labourquiescence,1893-1902

The year i890 was an important turning point in the economic and

political history of Argentina. For Di Tella and Zymelman 'the crisis of

I 890 is one of the most important in Argentine economic history, by virtue

of its magnitude and because of the political, social and economic

repercussions which accompanied it'.9 The Baring crisis in London and

the subsequent financial and trade dislocations proved a real boost to

industrialisatic in Argentina.

After the 1890 crash there was a generally recessive phase, punctuated

only by the upturn of I896. During this cycle, the level of investment

dropped significantly and immigration fell off, being overtaken even by

emigration for a while (see Graph 3). There was a labour surplus and the

economy showed little capacity for absorbing further labour. From this

date on the labour movement in Argentina was to express its opposition

to 'artificially fomented' emigration from Europe, which it saw as an

uncontrollable factor liable to increase the size of the reserve army of labour

and thus depress wages and make strikes more difficult to maintain. The

high immigration rates in I 896, for example, can be seen as a contributing

factor to the large proportion of working-class defeats in strike movements

that year. Indeed, such is the importance of immigration during these years

8

Julio Godio, Historiadel movimiento

obrerolatinoamericano:

r. Anarquistas

y Socialistas

I80o-IIr8 (Mexico; Editorial Nueva Imagen, i980), p. I65.

9 Guido Di Tella and Manuel

Zymelman,Los cicloseconomicos (Buenos Aires,

argentinos

Paid6s, I973), p. 32.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22 RonaldoMunck

that it must be considered as a substantial variable in our analysis of

economic cycles and labour insurgency.

Between i887 and I895 the number of industrial establishments rose

from 6,128 to 8,439 and the number of wage-earners doubled. As

mechanisation progressed, so too did the concentration of workers in

bigger plants. This changing rhythm of capital accumulation led to an

important shift in the configuration of the working class. Trades such as

the carpenters', bakers' and bricklayers', remained the main pole of

attraction for the incipient labour movement, though they were no longer

the leading sector in economic terms. The highly concentrated groups of

workers servicing the agro-export economy, such as the railway-workers

and the dockers, were now playing a strategic role in the trade union

world, leading the first nationwide strikes. It was in 1896 that the rail

workers led the first industry-wide strike which went beyond local limits.

A third, as yet minor, sector was represented by the workers in the large

meat-packing plants (frigorificos),who were subject to the real as opposed

to the formal subordination of labour.

It was during the course of this cycle that the labour movement went

beyond the early appeals to 'justice' and articulated the first working-class

programmes. Class solidarity, as exemplified in the first sympathy strikes,

was a clear sign that the language of class was beginning to gain ground

in the labour movement. In I897, for the first time there was also a

significant movement built around the question of unemployment. As Jose

Ratzer notes,' the proletarian protests are no longer relatively spontaneous

and isolated outbreaks. The resistance movement was raised to a higher

plane, it was generalized ... New unions were formed and others were

transformed ... The class as a whole was beginning to act'. ? In I 890 May

Day had already been celebrated in Argentina in an internationalist rally

addressed in several languages, in keeping with the diverse national origins

of the proletariat. In 1892, the first socialist organisation in Latin America

was formed when a group of German immigrants formed the Vorwirts

club. One of its leaders, German Ave Lallemant, had launched the

influential journal El Obrero(The Worker) in I890, which carried out a

pioneering analysis of the problems facing Argentina's fledgling labour

movement. The dominant tendency in the labour movement was, how-

ever, represented by the anarchists of various persuasions. The Italian

anarchist Errico Malatesta visited Argentina between I885 and 1889 and

encouraged anarchist involvement in the trade unions. After his departure

the individualists or 'anti-organisers' gained the upper hand, and this in

10 Jose Ratzer,Los marxistasargentinos

del90 (C6rdoba,Pasadoy Presente, 1969), p. 62.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Strugglein Argentina, 1890-1920 23

part accounts for the decline of labour agitation until 895. After that year,

the anarchists, and in particular the newspaper La Protesta Humana

(Human Protest) launched in 1897, turned their attention again towards

the unions and came to the forefront of labour organisation. Capital had

created a labour force and the anarchists and socialists were creating a

labour movement.

The labour movement was not born overnight, however. Indeed, the

industrialisation of the I 88os did not bear fruit in terms of a response from

labour until the i89os. This is because, as Hobsbawm writes, 'the habits

of industrial solidarity must be learned, like that of working a regular

week. So must the common sense of demanding concessions when

conditions are favourable, not when hunger suggests. There is a natural

time-lag, before new workers become an "effective" labour movement'."1

This learning period advanced considerably in the first cycle under

consideration here: I896-I 902. The factories and the workshops were not

the only arena of struggle during this period. In fact, as one popular labour

history argues, it was the overcrowded tenement buildings known as

conventilloswhich were 'the bitter site of a new cultural synthesis' between

the gringo and criollo workers.l2 These overcrowded, insanitary and

expensive living quarters brought the immigrant's aspirations into sharp

conflict with reality. Arguably it was not the capitalist factory which

unified the diverse proletarian strata-immigrants, craftworkers, established

local workers, internal rural migrants and others into a class, but the

conventillo.A number of rent strikes solidified the strong community

element in Argentina's working-class consciousness, and allowed the large

number of home-workers (mainly women textile outworkers) to engage

in struggle with the factory-based proletariat.

In terms of our correlation of economic indicators with the labour

struggles during this cycle several conclusions can be drawn. From the

data in the appendix we can observe that, although economic conditions

for capital were generally poor, wages increased steadily, albeit with ups

and downs (Table I and Graph I). The data we have available on strikes

are as yet incomplete, but we may note a significant increase in I896,

precisely the year of an upturn in the economic situation. After a lull of

nearly three years, when unemployment reached 40,000 in Buenos Aires

alone, strikes picked up again in I 900 and I 901, signalling a great upsurge

in labour militancy in the years to come. In November i902 the first

general strike took place in Argentina, preceded by a series of partial

11 Hobsbawm, 'Economic Fluctuations...', p. I44.

12

Guillermo Gutierrez, La clase trabajadoraracional(Buenos Aires, Crisis, 1978), p. 35.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24 Ronaldo Munck

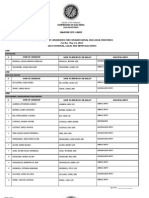

Table I. Economicconditions,wages,strikes, strikers, 189o0-190

Year Economic conditions Wages Strikes Strikers

1890 Downturn 120 4

I891 Poor I67 2

1892 Poor I90 7

1893 Poor 209 3

1894 Poor 174 9

I895 Poor 158 I9

1896 Upturn 145 26

1897 Downturn 162 0

1898 Poor 237 0

1899 Poor 288 0

1900 Poor 203

1901 Poor 223 100

1902 Poor 223 o00

1903 Upturn 220 o00

1904 Prosperous 252 I0oo

1905 Prosperous 250 o00

1906 Prosperous 233 I70 70,743

1907 Downturn 227 231 169,017

1908 Upturn 231 iI8 II,56I

1909 Prosperous 223 138 4,762

1910 Prosperous 240 298 i8,8o6

1911 Prosperous 240 102 27,992

1912 Prosperous 285 99 8,992

I913 Downturn New series 95 23,698

I9I4 Poor 68 64 14,I37

1915 Poor 6i 65 I2,077

I9I6 Poor 57 80 24,321

I9I7 Poor 49 I38 136,062

I918 Upturn 42 196 I33,042

1919 Prosperous 57 367 308,967

1920 Prosperous 59 206 I34,0I5

1921 Prosperous 73 86 I39,75

1922 Prosperous 84 II6 4I,737

I923 Prosperous 86 93 19,190

1924 Prosperous 85 77 277,078

1925 Downturn 89 89 39,142

1926 Upturn 90 67 15,880

I927 Prosperous 95 58 38,236

1928 Prosperous ioI 135 28,170

I929 Prosperous Ioo 113 28,27I

1930 Downturn 91 I25 29,33I

Sources:Economics conditions - Gilbert Merkx, 'Recessions and Rebellions in Argen-

tina, 1870-1930', Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 53, no. 2 (I973), p. 288.

Wages to I9I2 - Roberto Cort6s Conde, Elprogreso argentino,1880--914 (Buenos Aires,

Editorial, Sudamericana, I979), p. 227.

From 191 4 - David Tamarin, The Argentine Labour Movement in an Age of Transition,

1930-1945 (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, I977), p. 51.

Strikes/strikers to 1906: Godio, El MovimientoObreroy la cuestibn..., passim.

From I907: Jose Panettieri, Los Trabajadores(Buenos Aires, Editorial Jorge Alvarez,

1967), p. 201.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Strugglein Argentina, I890-1920 25

350-

280 -

140- I I

1\ I l/

/ '/

9- l / I

1898 1906 1914 1922 1930

Graph i. Wages ( ) and strikes (--), 890-1930. Sources as for Table i.

strikes and a general climate of heightened class struggle. The trade unions

were consolidated by the formation of the first confederation in I901: the

FederacibnObreraArgentina (Argentine Workers' Federation) (see Graph

2). However, trade union membership was no more than Io,ooo at this

stage. Immigration during this period tailed off after a peak in the late

I88os, although it is worth recalling that between i880 and 1900 1.5

million workers landed in Argentina, of whom nearly i million remained

in the country. The process of proletarianisation described by Marx was

taking place at one remove, as it were, as peasants and artisans from

Europe crossed the ocean to 'Fare 1'America'. As many readers' letters

to the newspaper El Obrerotestify, the immigrants' dreams rapidly faded

as they gradually came under the sway of capitalism and began forging

a new national working class. Significantly, the immigrants were integrated

into society first as workers and only much later as citizens.

III. Economic upturn and labour explosion, 1902-1908

The I902-8 cycle is characterised by a strong process of agrarian

development which accelerated the overall process of capital accumulation.

There was a strong boost to foreign and internal investment - fixed capital

investment increased by 38 % during this cycle. Predictably, immigration

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26 RonaldoMunck

I I I I I I I I I I I I 1

1900 1901 1904 1906 1908 1910 1912 1914 1916 1918 1920 1922 1924 1926

Graph 2. Trade-union membership, 1900-26. Source adapted

from De Shazo (I973: I3).

1890 1900 1910 19:

Graph 3. Migration patterns in Argentina, I880-I930.

Source: Bourd6 (1974: i6o).

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Strugglein Argentina, 1890-1920 27

also began to increase steadily as small farmers and artisans in Europe, not

to mention the landless and unemployed, were attracted to Argentina by

tales of fabulous wealth. During this period one person in every two in

Buenos Aires was foreign-born, and of every ten foreigners there would

be five Italians, three Spaniards, one person from north-western Europe

and one from the Balkans or eastern Europe.13 Compared with the earlier

wave of immigration in the i88os this one moved predominantly into

industry rather than agriculture, thus effectively 'remaking' the working

class. These largely prosperous years for capital were also when labour's

first 'explosion' began. As Hobsbawm writes, 'all social movements

expand in jerks; the history of all contains periods of abnormality, often

fantastically rapid and easy mobilisations of hitherto untouched masses'.14

Political propagandists and labour organisers continued their work during

this period, moving into new areas to agitate, educate and organise.

This economic cycle begins with the general strike of 1902, which

marked a big step forward for labour and led to a shift in the strategy of

the employers and the state. Hitherto, governments had been relatively

noninterventionist with regard to worker-employee relations, restricting

themselves to sharp 'punctual' bouts of repression. From now on labour

struggles would meet a systematic state repression on the one hand, while

on the other, the various governments strove, unsystematically at first, to

introduce labour legislation. Sunday was established as a day of rest, the

work of women and minors was regulated and in 1907 the Departamento

Nacional de Trabajo(National Labour Department) was established. This

body was charged with enforcing of the new labour legislation and the

arbitration of industrial disputes, but at first its only effective function was

to collect statistics on strikes (greatly improving our data for the post- 907

period). The other aspect of the state's new policy was represented by the

Law of Residence, approved in 1902, which provided for the deportation

of 'foreign agitators', a measure which led to the expulsion of hundreds

of anarchist workers, including many who were born locally. Henceforth

repression against labour organisations became systematic and widespread,

with police and army attacks on strikers and demonstrators leaving a heavy

toll of dead and injured. In fact, many of the general strikes in the first

decade of the twentieth century were in response to this wave of

repression.

As a historian of Argentine anarchism, Iaacov Oveed, recounts, 'the

13 et AmeriqueLatine:Buenos

et immigration Aires(xix etxx siecles)

Guy Bourde, Urbanisation

(Paris, Aubier, 1974), p. 213.

14

Eric Hobsbawm, PrimitiveRebels(Manchester University Press, 1959), p. 105.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28 Ronaldo Munck

Argentine working class was in action without respite during 1902, and

its radical-combative spirit was strengthened by a series of big strikes and

through the use of methods new to the workers' struggle'.15 There were

major strikes in the ports of Buenos Aires, Rosario and Bahia Blanca, and

a general strike against the Law of Residence, which was thwarted only

by the government's declaration of a state of siege (a frequent device in

the decade to come). The early revolutionary socialists were displaced by

the reformist social democrats after the Socialist Party was formed in I 896.

In 1902 the socialists condemned the call for a general strike as 'an absurd

and crazy act' by the 'propagandists of violence'. It was the anarchists

who for the moment held the upper hand in the labour movement. In 1904

they led a general strike in Rosario, which was then dubbed the 'Barcelona

of Latin America'. The high point of anarchist influence was undoubtedly

the 1905 general strike in Buenos Aires. Another, as yet subordinate, trend

was emerging in the labour movement, however, and would eventually

eclipse these massive showdowns between labour and the state. The

printers who had formed the first union in I876 and led the first strike

in 1878, were now, in I906, pioneering the first collective agreement with

the employers and setting up the first comisionesparitarias (parity

commissios) to regulate the wage-bargaining process. However, the tide

had not yet fully turned towards order and regularity in industrial

relations.

During I903 and 1904, around one half of all strikes occurred outside

Buenos Aires, whereas the trend was reversed towards I907-09, when

strikes in the capital accounted for nearly three-quarters of the total.

Spalding concludes that 'this trend probably reflects a second wave of

organizational activity that began in the capital and then spread to other

areas'.16 This confirms a general tendency for 'explosions' of the labour

movement to extend organisation to hitherto disorganised social layers

and geographical areas. Another general shift took place around I907,

when there were more factory stoppages than 'political' strikes as

repression intensified, and also as a reflection of changed attitudes. The

statistics on strikes mask the fact that, in I907, two-thirds of all strikes

were lost by the workers, whereas by I910 this proportion was reversed

as the working class strove successfully to defend its organizations and

living standards. The defeats of the working class in the big confrontations

15

Iaacov Oveed, El anarquismoy el movimientoobreroen Argentina (Mexico, Siglo XXI,

I978), p. 246.

16 Hobart Spalding, OrganigedLabor in Latin America (New York, Harper and Row, I977),

p. 25.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Strugglein Argentina,1890-1920 29

of the general strikes did not preclude a steady advance on the factory floor.

It was precisely during this period that the syndicalists split away from

the Socialist movement, articulating first a revolutionary syndicalism along

Sorelian lines, but developing into an apolitical trade unionism in years

to come. Ultimately, the rise of syndicalism within the labour movement

was due to the unresolved conflict between anarchist idealism and socialist

reformism.

Turning to the general trends of this economic cycle, we note that the

economic conditions for capital were decidedly prosperous and wages

remained stable. There was a steady rhythm of strikes between 1902 and

1906 with a remarkable upsurge in 1907, a year of notable economic

downturn. Clearly workers were resisting the tendency of employers to

cut wages and felt sufficiently confident after several years of good

conditions to do so. This hypothesis is supported by the data on

trade-union membership (Graph 2), which show a steady increase in the

membership of the anarchist confederation F.O.R.A. (FederacibnObrera

Regional Argentina: Argentine Regional Workers' Federation), which

reached a peak of 3o,ooo members in i906. The more stable and reformist

socialist-led confederation, the U.G.T. (Union General de Trabajadores:

General Workers Union) also advanced steadily, if less dramatically,

during this phase to attain a membership of around 0o,ooo workers.

Finally, overseas immigration went through a tremendous boom (Graph

3), with the first decade of the zoth century showing a net number of

immigrants (centres minus exits) of over i million. Not surprisingly,

phases of economic expansion coincide with periods of massive influxes

of immigrants (1880-9, 1903-13 and 1919-29), whereas cyclical crises

(I890-96, 1901, 1913) and prolonged recessions (1890-1902, 1929-39 and

the First World War) led to a reduction or even interruption of the flow

of immigrants.17

IV. Economicupturnand labourmilitancy, o908-Ir14

During the 1908-14 cycle, agriculture completed its expansive phase as the

bulk of the land was brought under the sway of capital. Foreign investment

continued to flow into Argentina, and before 1913 conditions were

generally prosperous. The approaching world war led to a brusque

deterioration of economic conditions as foreign investment froze and

foreign trade began to dry up. Until then industrialisation had followed

the relatively easy path of servicing the agricultural economy, -frigorificos

and flour mills, for example. Yet by I 914 the structure of the working class

17

Bourde, op. cit., p. 6I.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

30 RonaldoMunck

had changed somewhat since the I895 census was taken. The number of

manual workers had increased from 78,000 to 195,ooo over this period,

but their proportion of the working population remained consistent at

around 3 %. The number of artisans and small merchants also increased

in number but their proportion of the working population decreased from

40% to 35 % representing a decline of the petty commodity mode of

production. Conversely the number of employees increased from 30,000

to 102,000 but also their proportion in the working population from I %

to 18 %. Trade union organisation was to spread in this period from the

manual workers into this category of white-collar employees, who were

the product of the development of capitalism, particularly in the capital

city of Buenos Aires.

The labour struggles continued space during this cycle. A government

survey of 1908 reported 23,438 due-paying members in Buenos Aires out

of 214,370 workers in the various branches of industry. However,

although unionisation levels were low, strikes usually brought into action

much larger numbers. For example, the general strike of I907 mobilised

93,000 workers of whom only io,ooo were paid-up union members. This

pattern of activity continued with the general strike of 1909, called after

police repression of the annual May Day commemoration. The strike

achieved the freedom of the imprisoned workers and ensured the re-

opening of the union offices. In 1910 a general strike called to disrupt the

region's independence centenary celebrations was controlled by a state of

siege which left Buenos Aires looking like an armed camp and the jails

full of workers. The labour movement was now forced onto the defensive,

although strikes continued in various sectors of industry throughout the

period. Taking a broad view of the strikes which occurred between 1907

and 1913, we find that, of I,ooo strikes, 600 were lost by the workers, 300

were won and o00 were considered a 'draw'. Labour had continued the

impetus of its earlier struggles, but a fundamental change had occurred

in the course of this economic cycle.

Before 910o the labour movement was able to organise and press

forward its demands in conditions of relative disorganisation within the

ruling classes. Spalding exaggerates somewhat, but correctly grasps the

essential point: 'the agrarian elements did not react harshly to organization

by industrial workers so long as it did not threaten them directly. A

relatively strong urban movement thus could form without constant

harassment from the state'.18 Through its employers' association, the

Union Industrial Argentina (Argentine Industrial Union), the incipient

18

Spalding, op. cit., p. 32.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Struggle in Argentina, I890o-I92 3

industrial bourgeoisie began to play a far more aggressive role and

obtained the systematic aid of the state in repressing and co-opting the

working class. This last element is also important because around this

period there was a fundamental reform of the oligarchic state, drawing the

middle class and the top layers of the working class into the political arena.

In 1912 an electoral reform law was approved by Congress which

enfranchised the native male workers but not women or foreign-born

workers. This law was designed to incorporate the growing middle layers

represented by the Radical Party, and allow the Socialist Party to become

the voice of the 'respectable' working class, which could thus be weaned

away from anarchism. This strategy of 'preventive co-optation' bore fruit

with the victory of the Radicals in the I 9 I 6 elections, although the Socialist

Party never became a mass working class party in spite of its electoral gains

(48,000 votes in 1913).

There were also causes internal to the labour movement which help

explain the apparent decline of militancy after 9 0. The big general strikes

of 1902, 1905 and I909 found their natural limits in 19I0 - workers are

not 'naturally' inclined towards these dramatic displays of'revolutionary

gymnastics', each of which left a heavy toll of militants jailed, deported

or simply dismissed from work. Above all, it was the very success of the

economic struggles which blunted the political consciousness of the

working class. The anarchists, or anarcho-syndicalists as they had now

become, were also at least partly responsible for this. Anarchism had

effectively corresponded to the real conditions and aspirations of a

heterogeneous mass of independent workers only just emerging into

industrial capitalism. Their political perspective also accorded with the

reality of a bourgeois state impervious to workers' demands, but with the

possibility of gaining real victories through 'direct action' owing to a

certain degree of employer disorganisation. Now the bourgeois state had

come of age, and it intelligently blended repression with co-option. In the

new conditions the anarchists were being replaced in the leadership of the

labour movement by the syndicalists who, as Rock describes, 'stressed

continuously the value of tactics, and the virtues of co-ordination, timing

and planning [which] quickly overshadowed the lip service the movement

paid to the goals of class revolution'.19 The anarchists had contributed

greatly to the 'political education' of the working class, but were unable

to adapt to the new situation and provide a rounded political alternative

for labour.

19 David

Rock, Politics in Argentina, I89o-190o: The rise andfall of Radicalism (Cambridge

University Press, I975), p. 85.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32 Ronaldo Munck

Taking an overall view of this cycle we find that it was generally

prosperous until 9 3 when a recession set in. Wages showed a steady and

significant upward trend with a steady rhythm of strikes involving

significant layers of the working class. Trade-union membership remained

stable, with a significant degree of unity being achieved in 1914 when the

syndicalist confederation C.O.R.A. Confederacion ObreraRegionalArgentina

(Argentine Regional Workers' Confederation) merged with the anarchist

F.O.R.A. Immigration reached its highest peak ever in 1912, declining

dramatically when the World War started shortly afterwards. From 1907

onwards there was a marked labour surplus in Argentina but immigrants

continued to pour into the country. Significantly, this did not curtail the

high degree of self-activity which labour maintained during the period.

This phase confirms the hypothesis advanced by Hobsbawm that labour

'explosions' tend to occur in the cyclical upswing and less at the bottom

of slumps.20 There was also a sharp increase in the cost of living during

this period, as Spalding notes: 'from I906 or I907 there was a marked

rise in prices and rent, accelerating up to I914, helped by the crisis of

91 1-1912 and the economic insecurity caused by the First World War.

This rise annulled the improvements achieved by the working class in the

preceding years'.21 This conforms exactly to the conditions outlined by

Trotsky to account for upsurges in strike activity.

V. Economic transformation and labour recomposition, 1914-I917

The 1914-17 cycle is, of course, a depressive one: investment slumps,

immigration collapses and strikes decline dramatically. This is an extremely

important transition phase, marking, as Di Tella and Zymelman write,

'the change from an agrarian economy on horizontal expansion, towards

an economy which can only expand by changing its structure, sectoral

distribution and productivity'.22 This restructuring led to more than the

simple collapse of small semi-artisanal firms cut off by the war from their

source of raw material and fuel. Indeed, it marked a global shift in class

relations and a substantial recomposition of the working class. The

de-facto protectionism resulting from the disruption of trade during the

war gave an important boost to small and medium-sized national industry,

particularly in the textile sector, where the import substitution process

accelerated. This process of industrial expansion and concentration was

20

Hobsbawm, 'Economic Fluctuations...', p. 132.

21 Hobart (Buenos Aires, EditorialGalerna,1970),

Spalding,La clasetrabajadora

argentina

p. 42.

22 Di Tella and Zymelman, op. cit., p. 134.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Strugglein Argentina, I890-I920 33

reflected in the fact that more industrial establishments were set up

between 9 o and I9 9 than in the whole period 85o0-I909. Alongside

the small workshops there was now a significant number of large industrial

plants: there were several textile firms employing between 5oo and 1,5oo

workers and over ioo metallurgical plants in Buenos Aires alone employ-

ing an average of I 5o workers each, as well as the big sugar mills (ingenios)

of the north west which employed an average of ,000o workers each. There

was effectively a 'new' working class in the making.

During the war, strike activity declined significantly as compared with

the pre-war period. The economic recession led to an increase in the rate

of unemployment from 14 % in 19I4 to 20 % in 19I7. The cost of living

rose steadily and wages declined by one third over the same period. By

19 7, however, as the economic situation began to improve, strike actions

increased again. The strikes of that year differed significantly from those

in the explosion of 1907, in that whereas then the most affected sector was

small-scale industry, in I917 three-quarters of the strikers were involved

in transport activities. Of particular importance were the strikes organised

by the powerful maritime union the FederacibnObreraMaritima (Maritime

Workers' Federation) in 9 6 and I917. Under the Radical Party govern-

ment of Hipolito Yrigoyen, which came to power in 1916, these key

workers were able to negotiate a favourable settlement. On the other hand,

when the refuse collectors of Buenos Aires came out on strike in 1917 the

government did not hesitate to use repression against a sector which was

neither economically nor politically strategic. There were other significant

strikes in the course of 1917, including a general strike on the railways

and by the frigorifico workers who were to be a leading sector in the

trade-union movement after 1930. Significantly, around one-third of all

strikes during this cycle were carried out in defence of trade-union rights

to organise.

The tendency towards a system of arbitration and conciliation in

industrial relations intensified during this phase. In 19I6 the conciliation

mechanisms of the National Labour Department were actually put into

practice, and this agency also began to oversee the implementation of

labour legislation through its labour inspectors. Presidential arbitration

settled a number of disputes, although in some cases this was simply

designed to curry favour with key sectors of workers who might defect

to the Socialist Party in elections. Nevertheless, in spite of its inconsist-

encies and hesitations, the state was beginning to recognise the limitations

of its earlier stances that 'the labour question is a matter for the police'.

Through its policy of negotiations and compromise the government had

2 LAS 19

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34 RonaldoMunck

effectively accorded de-facto recognition to the trade-union organisations.

This naturally encouraged the numerical expansion of the trade unions,

after the briefly united labour confederation split in 9I 5 (Graph 3). The

syndicalist F.O.R.A. IX grew from 20,000 members in I915 to nearly

70,000 in 1920. The anarchist-led F.O.R.A. V, on the other hand, suffered

a sharp decline in numbers as this tendency lost its hegemony within the

broader labour movement, although its membership picked up signifi-

cantly after the dramatic events of 9 9, examined in the following section.

The syndicalist heyday lasted approximately from 1916 to 1920, during

which period they helped consolidate a stable system of industrial relations

amongst key sections of the working class such as the maritime and rail

workers. Significantly, they paid less attention to the meat packers in the

frigorificosand the metallurgical workers, two areas where Peron was to

gather widespread support in the 1940s. The Radical government fostered

good relations with the syndicalist labour confederation F.O.R.A. IX as

a means to establish a 'moderate' counterweight to the anarchists, and

using the 'anti-party' tendencies of this current to block socialist pene-

tration of the trade unions. During this period the service-sector workers

linked to the dynamic agro-export economy were the effective vanguard

of the trade-union movement, with industrial workers playing an as yet

subordinate role. One political current which began actively to promote

the industrial unions was the 'internationalist' or Bolshevik faction within

the Socialist Party, which eventually established itself as an independent

party in I9I8. These forerunners of the Communist Party rejected the

electoralism of the Socialist Party and declared that trade-union work was

equivalent to political activity as a means of struggle. The ideas of the

Russian Revolution in 19I7 also had a significant impact on the anarchists,

with a clearly defined anarcho-Bolshevik current playing an important role

in the next economic cycle.

The overall trends of the 1914-1 7 cycle should now be clear. Economic

conditions were poor until I 97 when investment began to pick up again

and employment patterns stabilised. Though unemployment was high it

was declining, and the abrupt cutting of the flow of immigration meant

that the reserve army of labour did not grow further. This set the scene

for a renewed bout of labour militancy after 1917 as workers strove to

make up wages to their pre-war level. During this phase the transition

from the petty commodity production stage of capitalism to that of

manufacture was completed, and the systematic extension of the division

of labour was accomplished. This of course had serious implications for

labour. As Ian Roxborough points out:

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Struggle in Argentina, I890-I920 35

as the leading sector shifts over time from one industry to another, there will

be a breakin the institutionalpatternof class relations ... The older pattern [of

class conflict] will almost certainlybe substantiallymodified in the process, and

labour organizationswill be restructured.23

As capital restructured, so did the labour movement - once the artisan

typesetter was the vanguard, then the bakers and dockers, the rail workers,

and finally the frigorificoworkers and those in textiles were poised to take

over the leadership of the movement. In the 1940s it would be the turn

of the metallurgical workers as the transition to 'big industry' was

consolidated.

VI. Economic upturn and labour recovery, 1917-I922

The cycle which followed the world war - 1917-1922 - was decidedly

prosperous as the country's primary goods were exported to war-torn

Europe. Investment now picked up again, and so did immigration.

Industry progressed steadily after initial fears that the renewal of compe-

tition would destroy the sectors built up under the de-facto protectionism

of the war period. Labour went through another 'explosion', seemingly

confirming a hypothesis mentioned by Hobsbawm that 'the great "leaps"

occur after exceptionally severe slumps, which impress workers with the

value of organization'.24 This was, indeed, a period in which previously

unorganised layers were brought into action, especially after 1919.

Furthermore, it confirms the view that a rising cost of living is a key

element in labour upsurges: it rose from o00 in 1914, to I35 in 1917 to

i86 in 1919.

Throughout this phase the level of labour activity remained at an

exceptionally high level. By I9I9 unemployment had declined to 8%

although real wages had dropped by about 30 % since 1965, as the post-war

inflation reduced the earning capacity of the working class. The scene was

set for some of the most dramatic confrontations between labour and the

state since the labour movement's formation. The anarchists appeared to

be in terminal decline as their failure to impose a call for a general strike

in 1918 testified. The now openly reformist syndicalists appeared to hold

the upper hand in the labour movement particularly given their

'understanding' with the Radical Government. No one therefore expected

an explosion of class conflict when the workers of a large metallurgical

plant on the outskirts of Buenos Aires walked out in December 1918,

23 Ian Roxborough, 'The Analysis of Labour Movements in Latin America: Typologies

and Theories', Bulletin of Latin American Research,vol. I., no. i ( 98 ), p. 91.

24

Hobsbawm, 'Economic Fluctuations...' p. 128.

2-2

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

36 RonaldoMunck

shortly after having formed a union. Clashes between strikers and the

police led to several deaths and a general strike was called by the anarchist

F.O.R.A. V, a call later backed by the larger syndicalist confederation, the

F.O.R.A. IX.

In the week that followed, a semi-insurrectionary general strike para-

lysed the city of Buenos Aires, and the state, aided by armed elements of

the middle class, unleashed terror on the workers' quarters, leaving 700

dead and 4,000 injured in its wake. The syndicalist F.O.R.A. IX decided

to lift the general strike, to which the socialists and communists agreed,

with only the reduced anarchist current remaining on the streets. The

army's intervention had allowed the government to negotiate with the

syndicalists who had established themselves as the interlocutorvalidoof the

working class. Of course, at another level the events of 9 9 represented

the eruption of a deep social crisis, the failure to integrate the immigrant

and the continued political marginality of the working class. One effect

of 1919 was to draw into the trade union movement wide layers of

hitherto unorganised workers, and to re-establish anarchism as a credible

force in the wider labour movement.

In his assessment of the SemanaTragica(Tragic Week), Rock concludes:

'in broad terms the general strike of 1919 was more a series of inarticulated

riots than a genuine working class rebellion'.25 Certainly, the strike was

ephemeral, limited geographically and in terms of its support; nor did it

receive any realistic revolutionary leadership. However, it was not simply

a 'chaotic outburst of mass emotion' as Rock suggests.26 A historical

conjuncture has greater social meaning than its discrete 'ordinary'

elements. The long-run view can sometimes obscure the symbolic sig-

nificance of key episodes in working-class history. The SemanaTragicawas

one such key conjuncture for the labour movement: it marked the last gasp

of the revolutionary anarchist tendency and, in the mode of its resolution,

a harbinger of a new, more stable, period of industrial relations.

In 1921 the rural equivalent of the SemanaTragicaleft a tragic toll when

the rural labourers on the estanciasof the southern province of Patagonia

launched a strike for improvements in their conditions. Over I,500

workers were killed by the army in a one-sided campaign, although in

1923 symbolic retribution was exacted by an anarchist immigrant who

threw a bomb at the colonel responsible for the massacre. However, this

was not the highpoint of I909, but the beginning of a new era, in which

the relations between labour, capital and the state were to be placed on

a more stable basis.

25 Rock, op. cit., p. I68. 26 Ibid.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ClassStrugglein Argentina,1890-1920 37

From I 890 to 1920 the labour movement of Argentina made remarkable

progress, with the formation and consolidation of the trade unions, the

election of political representatives to the parliamentary system, and the

gaining of significant social improvements for the working class. The

anarchists had, however, failed to translate their pre- 91o combativity into

a rounded political strategy for labour. On the other hand, the socialist

current split into 'apolitical' syndicalists and the parliamentary-oriented

mainstream, thus perpetuating a false divide between economic and

political labour struggles. There was also a failure to mobilise the rural

working population behind the industrial working class, and to articulate

the anti-imperialist perspective called for in a dependent nation. Indeed,

anarchists and socialists alike opposed protectionist measures for Argen-

tina's industrial sector, on the basis of an abstract internationalism. This,

indeed, was the factor which allowed Peron and nationalist historians to

describe the pre-i93o labour movement as a minority 'foreign' implant.

This entails denying the very real advances made by labour during this

period and its not inconsiderable impact on national history. We fully agree

with Godio's conclusion that during this period 'the successes in the trade

union and parliamentary fields were so notable that they made the

Argentine labour movement, in spite of its limitations, into the most

developed and prestigious throughout Latin America'.27

An overview of the 1917-22 period must stress the consistently

prosperous conditions for capital accumulation and the steady rise of

wages, which doubled during this cycle (Table i). Strike activity is

remarkable not so such in terms of the number of strikes but in the volume

of strikers: over oo00,000 workers were on strike nearly every year of this

cycle, with the figure for I9I9 topping the 300,000 mark. The level of

overseas immigration remained low until 1920 when it began to pick up,

but it was still well below the pre-war level (Graph 3). Trade union

membership peaked during this cycle, with the syndicalist F.O.R.A. IX

leading the way, but, paradoxically, it began to decline dramatically

towards the end of this phase (Graph 2). Both the anarchist F.O.R.A.

and the new revolutionary syndicalist confederation formed in 1922,

the Union Sindical Argentina (Argentine Trades Union), lost members

steadily in the following cycle. The explanation for this lies outside our

period but, essentially, economic prosperity and a political radicalisation

caused by the Russian Revolution tended to marginalise the trade unions.

When the new movement was eventually unified in 1930 to form the

CGT - Central Generalde Trabajadores(General Labour Confederation) -

27

Julio Godio, Historiadelmovimiento

obrero,p. 2I9.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

38 RonaldoMunck

it organised far fewer workers than the anarchists and syndicalists did

around 1920. The political hegemony of the anarchists (i902-9) and later

the syndicalists (I9'6-zo) had been followed by a period of realignment,

confusion and demoralisation which paved the way for Peron 's 'capture'

of the labour movement in I943-6.

VII. Conclusion

Without wishing to fall into the trap of sociological formalism, we can

say in conclusion that the working hypotheses we began with have been

largely borne out. The formation of the working class in Argentina, was,

indeed, the result of a broad and complex process of political and social

history, and not the simple result of mechanisation. As to the cycles of

class struggle, our findings bear out Hobsbawm's conclusion that

depressive phases accumulate 'inflammable material' but do not set it

alight. Thus the depression of the I89os accumulated grievances and

injustices which burst out in the strike wave of the early i9oos; likewise

the period of the First World War created the conditions for the postwar

upsurge of labour militancy. Later, as Trotsky and other observers/par-

ticipants in the class struggle have suggested, we found that strike waves

broke out in the economic upturn, usually accompanied by a rise in the

cost of living. This was the case in the 1906-7 strike wave, and likewise

in the period following the World War. Taken overall, we find that

Screpanti's hypothesis of two main variables - achievements and frus-

tration - helps explain the pattern of labour insurgency in Argentina.

Achievements, in terms of economic and social gains which may lead to

a decrease in workers' militancy, but may also accumulate social tension

as frustration results when economic growth slackens and capitalists

unload the cost in terms of higher prices and lower wages. In short, strike

patterns are more complex than those theories which relate them either

to poverty or the economic upturn.

It is important to bear in mind Trotsky's warning that while strike

movements are closely bound up with the conjunctural cycle, 'this must

not be considered mechanically'.28 This is precisely where Cronin's advice

is relevant, when he reminds us that economic cycles do not simply

produce economic growth, but restructure the working class and 'redraw

the lines of class cleavage throughout society and the parameters of

collective action'.29 The economic cycle associated with the World War led

28 Leon

Trotsky. 'The "Third Period" of the Comintern's Errors', Writings of Leon

Trotsky, p. 46.

29

Cronin, op. cit., p. 112.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Class Struggle in Argentina, 180-I192 39

to precisely such a transformation in Argentina. The restructuring of

capital led to a global recomposition of the working class, which involved

both objective and subjective elements (the political dimension, in short).

Finally, we must recall that our analysis has been restricted to the

business cycle and not the Kondratief type of long cycles. The whole

phase of 1890 to 1930 could be seen as a long wave in Argentine terms;

but there would be many problems in applying this approach to an open

and agrarian economy such as Argentina's. Furthermore, even though

some authors such as Mandel recognise that 'extraeconomic factors play

key roles'30 in long waves, most works play down the element of political

agency. We cannot, in short, understand the social and economic history

of Argentina during the early zoth century without considering the active

role of anarchist and socialist militants. Though strike patterns were

affected by economic cycles, the working class did in a very real sense

'make' itself in the process of class struggle.

30

Ernest Mandel, Long Waves of Capitalist Development - The Marxist Interpretation

(Cambridge University Press, I980), p. 20.

This content downloaded from 128.228.173.41 on Thu, 26 Sep 2013 13:12:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Causes of The Industrial RevolutionDocumento8 pagineCauses of The Industrial RevolutionDivang RaiNessuna valutazione finora

- MUNK - Cycle Class StruggleDocumento23 pagineMUNK - Cycle Class StrugglealejandroNessuna valutazione finora

- Export-Led Growth in Laitn America 1870 To 1930Documento18 pagineExport-Led Growth in Laitn America 1870 To 1930sgysmnNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Unrest in Argentina, 1887-1907 Author(s) : Roberto P. Korzeniewicz Source: Latin American Research Review, Vol. 24, No. 3 (1989), Pp. 71-98 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/06/2014 12:44Documento29 pagineLabor Unrest in Argentina, 1887-1907 Author(s) : Roberto P. Korzeniewicz Source: Latin American Research Review, Vol. 24, No. 3 (1989), Pp. 71-98 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/06/2014 12:44Ali GhadbounNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing The Obstacles To Industrialisation: The Mexican Economy, 1830-1940Documento33 pagineAssessing The Obstacles To Industrialisation: The Mexican Economy, 1830-1940api-26199628Nessuna valutazione finora

- Labour Intensive Globalisation in Global HistoryDocumento55 pagineLabour Intensive Globalisation in Global HistoryWilliam AllelaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Bird's Eye View of Brazilian Industrialization: André VillelaDocumento28 pagineA Bird's Eye View of Brazilian Industrialization: André Villelacarlill0sNessuna valutazione finora

- Process of Industrialization: The Growth of CitiesDocumento3 pagineProcess of Industrialization: The Growth of CitiesDeep HeartNessuna valutazione finora

- TCWD Week2-5 CompilationDocumento16 pagineTCWD Week2-5 CompilationSANTOS, CHARISH ANNNessuna valutazione finora

- Economy in The Gilded Age HandoutDocumento3 pagineEconomy in The Gilded Age Handoutapi-253453663Nessuna valutazione finora

- Industrialisation Mod-1 LatestDocumento42 pagineIndustrialisation Mod-1 LatestsolomonNessuna valutazione finora

- Revisiting Industrial Policy and Industrialization in Twentieth Century Latin AmericaDocumento7 pagineRevisiting Industrial Policy and Industrialization in Twentieth Century Latin AmericaHenrique SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Trade An Italian Immigrant For Coffee - A Historical Case Study of Market Failure in 20th Century BrazilDocumento17 pagineHow To Trade An Italian Immigrant For Coffee - A Historical Case Study of Market Failure in 20th Century BrazilGiovannaNessuna valutazione finora

- In Defense of Domestic Market, Perú - 1930sDocumento24 pagineIn Defense of Domestic Market, Perú - 1930sFranco Lobo CollantesNessuna valutazione finora

- On New Terrain: How Capital Is Reshaping the Battleground of Class WarDa EverandOn New Terrain: How Capital Is Reshaping the Battleground of Class WarValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- (Defraigne - Jean - Christophe) - La - Reconfiguration - Industrielle English Translation 2016Documento28 pagine(Defraigne - Jean - Christophe) - La - Reconfiguration - Industrielle English Translation 2016Joana LopesNessuna valutazione finora

- TCWD Week 3 Market IntegrationDocumento7 pagineTCWD Week 3 Market IntegrationEveryday ShufflinNessuna valutazione finora

- By Hans-Joachim Voth: I. Discontinuity Models and The Industrial RevolutionDocumento12 pagineBy Hans-Joachim Voth: I. Discontinuity Models and The Industrial RevolutionΜιχάλης ΘεοχαρόπουλοςNessuna valutazione finora

- How Did Developed Countries Industrialize? The History of Trade and Industrial Policy: The Cases of Great Britain and The USADocumento35 pagineHow Did Developed Countries Industrialize? The History of Trade and Industrial Policy: The Cases of Great Britain and The USAGairuzazmi M GhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Opportunity Lost: Economic Development in ArgentinaDocumento10 pagineOpportunity Lost: Economic Development in ArgentinaRobert KevlihanNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanley Planes and Screw Threads - Part 2 PDFDocumento28 pagineStanley Planes and Screw Threads - Part 2 PDFrefaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalization: Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyDocumento14 pagineGlobalization: Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyHa LinhNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER.10 Growth, Immigration and MultinationalsDocumento45 pagineCHAPTER.10 Growth, Immigration and MultinationalsAnjali sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionDocumento26 pagineEnglish Workers' Living Standards During The Industrial RevolutionKrissy937Nessuna valutazione finora

- Britain and France:: Modern World HistoryDocumento5 pagineBritain and France:: Modern World HistoryUsman ShafiqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Rage Against The Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing EnglandDocumento56 pagineRage Against The Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing EnglandKosta TonevNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Industrialization, How Europe Transformed Into A Labour Market, How Working Class Emerged in Europe, Analyze Theory For The Formation of European Working ClassDocumento9 pagineWhat Is Industrialization, How Europe Transformed Into A Labour Market, How Working Class Emerged in Europe, Analyze Theory For The Formation of European Working ClasstadayoNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Industrialisation?: Agrarian Society Industrial Economy ManufacturingDocumento16 pagineWhat Is Industrialisation?: Agrarian Society Industrial Economy ManufacturingSurya YerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Irigoin, Maria Alejandra - Inconvertible Paper Money, Inflation and Economic Performance in Early NineteenthDocumento28 pagineIrigoin, Maria Alejandra - Inconvertible Paper Money, Inflation and Economic Performance in Early NineteenthafrendesNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Revolution 2Documento10 pagineIndustrial Revolution 2Saubhik MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambridge British Industrial RevolutionDocumento38 pagineCambridge British Industrial RevolutionRachael VazquezNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 R. Industrial y M. ObreroDocumento6 pagine1 R. Industrial y M. ObreroLucía Torres VizcaínoNessuna valutazione finora

- Economy in The Gilded AgeDocumento16 pagineEconomy in The Gilded AgeGilia Marie SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History: P G L A D T CDocumento40 pagineDiscussion Papers in Economic and Social History: P G L A D T COmar David Ramos VásquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial RevolutionDocumento3 pagineIndustrial RevolutionMajharul IslamNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambridge University PressDocumento31 pagineCambridge University PressPaco Corona FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- GPI Policy Paper No.27Documento9 pagineGPI Policy Paper No.27Valbona RamallariNessuna valutazione finora

- Reader CHP 3Documento26 pagineReader CHP 3ZeynepNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor and GlobalizationDocumento21 pagineLabor and GlobalizationScott Abel100% (1)

- Documento Sin TítuloDocumento10 pagineDocumento Sin TítuloCarmen Benavides UscangaNessuna valutazione finora

- The J-Curve and Power Struggle Theories of Collective ViolenceDocumento5 pagineThe J-Curve and Power Struggle Theories of Collective ViolenceNina SpaltenbergNessuna valutazione finora

- Russian IndustrializationDocumento10 pagineRussian IndustrializationMeghna PathakNessuna valutazione finora

- The New International Division of LabourDocumento22 pagineThe New International Division of LabourCarlos WagnerNessuna valutazione finora

- Wiley Economic History SocietyDocumento28 pagineWiley Economic History Societyxandrinos22Nessuna valutazione finora

- Outline For Each TopicDocumento2 pagineOutline For Each TopicJuan LamaNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing - Installment 4 - Industrial Robin LapertDocumento5 pagineWriting - Installment 4 - Industrial Robin LapertJulie De LamareNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ottoman Empire in The "Great Depression" of 1873-1896Documento13 pagineThe Ottoman Empire in The "Great Depression" of 1873-1896hamza.firatNessuna valutazione finora

- Contours of World Economy - ReviewDocumento4 pagineContours of World Economy - Reviewdevendra_gautam_7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial RevolutionDocumento23 pagineIndustrial Revolutionkato chrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Conference of Socialist Economists Bulletin Winter - 73Documento109 pagineConference of Socialist Economists Bulletin Winter - 73Tijana OkićNessuna valutazione finora

- Hugo Guerrero1Documento1 paginaHugo Guerrero1api-301102008Nessuna valutazione finora

- INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION and FRENCH REVOLUTIONDocumento4 pagineINDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION and FRENCH REVOLUTIONMuhammad HasnatNessuna valutazione finora

- The British Industrial Revolution in Global PerspectiveDocumento41 pagineThe British Industrial Revolution in Global PerspectiveFernando LimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Findlay, R., O'Rourke K.H., 2007. Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and The World Economy in TheDocumento9 pagineFindlay, R., O'Rourke K.H., 2007. Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and The World Economy in TheAdrian RoscaNessuna valutazione finora

- Capitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryDa EverandCapitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (9)

- The Economic History Review - February 1992 - BERG - Rehabilitating The Industrial Revolution1Documento27 pagineThe Economic History Review - February 1992 - BERG - Rehabilitating The Industrial Revolution1yoona.090901Nessuna valutazione finora

- 19-20 7B Lecture 05 Slides Colossus-Industrial Revolution PDFDocumento22 pagine19-20 7B Lecture 05 Slides Colossus-Industrial Revolution PDFKert MantieNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Is at IonDocumento24 pagineIndustrial Is at IonDavid IbhaluobeNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Globalisation On World WarslDocumento18 pagineEffect of Globalisation On World WarslShrayan BarmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Industrial Revolution Started in England Around 1733 With The First Cotton MillDocumento3 pagineThe Industrial Revolution Started in England Around 1733 With The First Cotton MillKach KurrsNessuna valutazione finora

- WWW - Ignou-Ac - in WWW - Ignou-Ac - in WWW - Ignou-Ac - In: The Relevance of Non-Alignment TodayDocumento7 pagineWWW - Ignou-Ac - in WWW - Ignou-Ac - in WWW - Ignou-Ac - In: The Relevance of Non-Alignment TodayFirdosh KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Critical Race Theory - A Brief History Explained - The New York TimesDocumento5 pagineWhat Is Critical Race Theory - A Brief History Explained - The New York TimesCelia EydelandNessuna valutazione finora

- Francis Fukuyama Predicted The End of History. It's Back (Again)Documento4 pagineFrancis Fukuyama Predicted The End of History. It's Back (Again)dpolsekNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Potential and AlientationDocumento10 pagineHuman Potential and Alientationhannah hipe100% (1)

- Adolf Hitler BiographyDocumento10 pagineAdolf Hitler BiographyJas Lerma OrtizNessuna valutazione finora

- German CrisisDocumento3 pagineGerman CrisisRăzvan NeculaNessuna valutazione finora

- A3 Development of Dictatorship Germany 1918-1945Documento12 pagineA3 Development of Dictatorship Germany 1918-1945fadum099Nessuna valutazione finora

- Russian Revolution (1917)Documento19 pagineRussian Revolution (1917)Nikesh NandhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aristocracy: Basic Forms of GovernmentDocumento5 pagineAristocracy: Basic Forms of Governmentgritchard4Nessuna valutazione finora

- John Michell, Radical Traditionalism, and The Emerging Politics of The Pagan New Right. - Amy Hale - Academia - EduDocumento18 pagineJohn Michell, Radical Traditionalism, and The Emerging Politics of The Pagan New Right. - Amy Hale - Academia - EduSolomanTrismosin50% (2)

- Upsc Epfo 2020: Industrial Relations & Labour LawsDocumento24 pagineUpsc Epfo 2020: Industrial Relations & Labour LawsSwapnil TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Conspiracy To Rule The World - Illuminati MapDocumento1 paginaConspiracy To Rule The World - Illuminati MapKeith KnightNessuna valutazione finora

- B.A. (Prog) History 6th Semester-2023Documento8 pagineB.A. (Prog) History 6th Semester-2023guptaaamit30Nessuna valutazione finora

- Russia 1905 1941 EnglishDocumento76 pagineRussia 1905 1941 EnglishUdval SmileNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Destroy A CountryDocumento19 pagineHow To Destroy A CountryJennifer Jacinto WeberNessuna valutazione finora

- Secularism and Indian Politics: Name of The TopicDocumento30 pagineSecularism and Indian Politics: Name of The TopicYogesh Madan DharanguttiNessuna valutazione finora

- Attitudes Toward Anschluss 1918 1919Documento13 pagineAttitudes Toward Anschluss 1918 1919Idan SaridNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Cultural RevolutionDocumento18 pagineOn The Cultural RevolutionIvánTsarévichNessuna valutazione finora

- الحق في الإعلام والحق في الاتصالDocumento9 pagineالحق في الإعلام والحق في الاتصالsidahmadmostefaoui8Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rise of The Dictators in The 1920Documento16 pagineRise of The Dictators in The 1920krats1976Nessuna valutazione finora

- Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)Documento248 pagineDomenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)PartigianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rundell - 2009 - Democracy Across Borders From Dêmos To DêmoiDocumento8 pagineRundell - 2009 - Democracy Across Borders From Dêmos To DêmoiSergio MariscalNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Rights in CanadaDocumento1 paginaHuman Rights in CanadaRohish MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shri Devaraj Ars & Social Justice in KarnatakaDocumento4 pagineShri Devaraj Ars & Social Justice in Karnatakadominic100% (1)

- Lenin and The Aristocracy of LaborDocumento7 pagineLenin and The Aristocracy of LaborkrishkochiNessuna valutazione finora

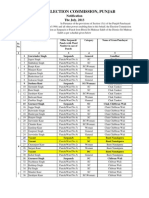

- State Election Commission, Punjab: Notification The July, 2013Documento19 pagineState Election Commission, Punjab: Notification The July, 2013gurvindersinghatwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Zeev Sternhell The Idealist Revision of Marxism The Ethical Socialism of Henri de Man 1979Documento23 pagineZeev Sternhell The Idealist Revision of Marxism The Ethical Socialism of Henri de Man 1979Anonymous Pu2x9KVNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study: Political PartiesDocumento26 pagineCase Study: Political PartiesChaii100% (1)

- Toward The White RepublicDocumento11 pagineToward The White RepublicHugen100% (1)

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 pagineCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNessuna valutazione finora