Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Examining Competition in The Classroom H

Caricato da

Chinh XuanTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Examining Competition in The Classroom H

Caricato da

Chinh XuanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Examining Competition in the Classroom: Healthy and Unhealthy Uses

John Shindler, Professor

California State University, Los Angeles

www.transformativeclassroom.com

Defining Competition

Likely Consequences and Benefits of Competition

Healthy vs. Unhealthy Competition

Classroom Applications

Competition in the Transformative Classroom

When we were students, some of us had positive experience with competition, while

others had experiences that were more often painful or at best not very enjoyable. As

adults, we commonly take that view of competition that we formed when we were

students ourselves, and then apply it to what we believe is appropriate and right for our

students and/or children; consequently, we may be operating from unexamined

assumptions. As a result, it is possible that our students are paying the price for our lack

of awareness. Therefore, it may be instructive to consider the effects of competition as

objectively as is possible, as we try to find an appropriate place for it in our classroom.

In this chapter we examine the nature of competition as well as its place in the

classroom. We will distinguish what could be considered the healthier forms of

competition from those that are less healthy, and examine if and when it can be

incorporated into the transformative classroom.

Chapter Reflection 19-a: Recall your experiences of competition as a student. What is

your association with it as a result? How does your perception vary from that of others

you know? How has your perception affected the way you use (or plan to use)

competition in your classroom.

Defining Competition:

The definition of human competition is a contest in which there are two or more people

engage in a contest where typically only one or a few participants will win and others will

not (Webster, 2007). By definition competition exists when there is a scarcity of a

desired outcome. Individuals and/or groups are then in a position that they must vie for

the attainment of that outcome. For example in team athletics, two teams engage in a

sport for the purpose of winning.

It is partially true that the world is competitive. It is difficult to avoid competition entirely in

life. But it is also true that for the most part, competition in life is a self-imposed or at

least self-selected condition. We can just as easily live an existence defined more by

collaborative and self-referential goals than by competition with others. So to say that the

real world is inherently competitive is for the most part a myth. Moreover, to say that we

are preparing students for the real world by putting them in artificially constructed

competitive situations is to impose our world-view on them. In fact, one could argue that

in a broad sense, collectively, we as educators create a more or less competitive future

world by the way we encourage our students to think and treat one another. In other

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-1

words, if we create a more cooperative environment in our schools we create the

likelihood of a more cooperative future world, whereas, if we create more competitive

environments, we create a more competitive world in the future.

Chapter Reflection 19-b: In your ideal world, what is the role of competition? Keep this

answer in mind as you reflect on the role that you want competition to play in the world

of your classroom.

The Affect Competition Has on any Situation

When we introduce the competitive element into a situation, we find that in essence it

creates a sense of external urgency and drama. Competition brings a variable into the

equation that shifts the participants attention from the task itself to attention to the cost

of their performance in the task. For example, if the task were to assemble a model

airplane, we could make it into a competition declaring the model making activity a race

to see who could finish the task first. Consider how this competitive element changes the

participants thinking. The sense of urgency (for anyone who cares about winning, and

that may not be everyone) is elevated to some degree. An external drama is now

introduced. The purpose of the activity inherently shifts away from the learning goals

(i.e., engagement in making sense of the various elements of the process and the

attempt to interpret and perform a quality effort to goals related) to efficiency, speed and

the outcome relative to others. As a result the activity becomes less something in which

to engage in and of itself and becomes more a means to an end (winning). The process

or at least reflecting on the process of the task becomes less important than the product.

For the most part, we can see this change in focus occurring no matter what the teacher

may say either to encourage or to discourage it. The structure by its nature encourages

the shift in the attitude of the participant.

Chapter Reflection 19-c: Recall a situation where you or someone else was involved in

a race to complete a task. Was there more mistakes being made as a result? Was the

quality of the performance better or worse? How do you explain your observations?

Introducing competition into the context of a group efforts, we can see much of the same

shift in attitude occurring. When competitive goals are present, the group will tend to

place an increased value on the outcome of the effort and decrease their focus on the

process. In other words, they will increase the attention that is placed upon doing what it

takes to win, and decrease the attention placed upon learning for its own sake. In

addition the competitive element will have an effect on the group dynamics as well. For

example, suppose that we ask groups to work in teams to assemble model airplanes,

and set up a reward for the group that finishes first or creates the best product. If we

contrast this competitive condition to a purely collaborative condition, the likely result will

be that group members will change the way they regard one another. The competitive

condition encourages one to view their fellow group members less as peers or a vehicle

for learning, and more those to be used to reach the goal. Such behaviors as dialogue

and reflection are useful in the collaborative condition, whereas in the competitive

condition, they often slow the process and diffuse the groups focus. In a collaborative

condition divergent ideas can usually be explored without penalty, whereas when we

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-2

introduce the element of competition it creates a disincentive to dialogue, or reflect any

more than is necessary to accomplish the task.

In a collaborative condition there is no disincentive to involve the efforts of the less

dominant and/or competent members of the group. In the competitive condition however,

it is likely that some combination of personality dominance and individual level of

competence will define the values of the process, inevitably marginalizing weaker and

less competent team members. Even with good will and/or good intentions being present

at the beginning of the process, these trends are likely as the structural incentive in a

competitive condition itself will inherently promote both a shift in the focus of the task

and the nature of the team dynamics.

Chapter Reflection 19-d: Recall your own experience in group to group competition.

What was the attitude of the others? Did everyone in the group enjoy the experience

(even on a winning team)? If not, why not?

A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Use of Competition

If we were to compare the potential benefits of competition to the potential costs, we find

that there are a good number of reasons to be cautious about using competition. While

competition can instantly infuse fun and drama into the equation, there is a cost. Aside

from the shift from process to product focus described above, there are addition likely

consequences such as promoting a fear of failure and undermines the students intrinsic

motivation. Figure 19.1 outlines this cost benefit analysis.

Figure 19.1 Likely Consequences and Potential Benefits of Competition

Likely Consequences of Competition:

Promotes a shift from means/process to ends/products

Brings an external dimension into the equation, and weakens the students intrinsic

motivation.

Heightens the level of anxiety/threat

Promotes a tendency to take on a mentality defined by fear of failure (and

consequently winning becomes the way to relieve the anxious condition) and

consequently a helpless pattern.

In groups:

o Shifts the emphasis from quality relationships to effective relationships

o Decreases incentive to think reflectively or divergently

o Accentuates the effects of existing social hierarchy and ability levels

o Decreases the sense of bond generally among groups (i.e., community) and

temporarily increases the bond within the winning group.

Potential Benefits of Competition:

Increases the level of anxiety/threat for a performance (pressure may potentially help

refine skill given a more demanding performance context).

Can provide a dimension that can potentially reinforce group interdependence an/or

team skills.

Can potentially increase the level of fun and/or drama in an activity.

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-3

Chapter Reflection 19-e: Reflect on the costs and benefits of competition listed above.

In your opinion does one list outweigh the other?

While the list of potential costs related to competition is more substantial than its list of

potential benefits, the power of its effect makes its use very tempting. Typically, we find

that little else will get a group of young people more energized than when we introduce

competition into the equation. But like the use of any of the other extrinsically motivating

practices, the short-term benefits can mask the long term detrimental effect. As is

necessary when we consider the use of extrinsic rewards or other loaded strategies,

we need to be intentional and careful in our use of competition.

Use of Competition in the Classroom:

There are those that subscribe to position that there is no such thing as healthy

classroom competition. Yet, while it can be debated whether competition should be

incorporated in schools at all, the fact is that it is a prevalent practice and will likely be so

for some time. Therefore it is useful to distinguish healthier forms of competition from

those that are less healthy. There are a few principles to consider when judging whether

a competitive classroom situation is more or less beneficial.

First, competitions for valuable outcomes will have more detrimental effects on a class

than competitions for trivial and/or symbolic outcome. There are essentially three types

of valuable/real outcomes. They are a) material things of value - this includes privileges

that have a substantive impact, b) the teachers conspicuous and/or lasting affection,

and c) recorded grades. When we give students a meaningful reward for winning, we

make the winning what is important, and we make the statement that students should

care at least as much about getting the reward as they do about the quality of their effort.

Recalling our discussion of motivation in Chapter 7, when we do this we have drawn the

intrinsic motivation out of the situation by introducing an extrinsic reward.

Second, the shorter the life of the competition the more likely it is to have a beneficial

effect. The length of the contest will increase its sense of prominence and decrease its

sense of intensity and fun both undesirable effects. For example, if we keep track of

the number of books each student has read over the course of the semester and post

the tally on a chart on the wall of the classroom, the initial effect may be an increased

sense of motivation to read books. Therefore, we initially might assume that our strategy

has been effective. However, as the contest goes on, we will notice that students will

increasingly read books just for the sake of the contest, and will have an incentive to

falsify the number of books that they have read. Moreover, over time we will notice that

the competition is becoming less fun and increasingly more of a burden. At the end of

the year, the competition will have produced essentially one somewhat happy and very

relieved student, many students who feel unhappy about losing, a good number who will

feel a little unhappy but highly relieved that the chart is no longer being held over their

head and shaming them.

Third, the leader of the competition needs to place a conspicuous emphasis on the

process over the product. If the winning is the point, the students will take on a do what

it takes attitude. If the students are encouraged to value the process, they will feel

justified stay focused on the learning outcome and feel assured that it is okay to put their

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-4

attention into quality as the goal. However, enabling this mindset is only possible when

the context itself does not place so much value on winning that the leaders emphasis

falls on deaf ears. Therefore the two first principles become prerequisite.

When taken together we could conclude that the most healthy and beneficial

competitions are those that are undertaken for exclusively symbolic value (e.g., good

job you won polite applause for the winners congratulations to group four they came

up with some great ideas and won the contest.), are short and sweet, are characterized

by all participants feeling like they have a chance to win, and have the process and

quality of work being given conspicuous value, and the product of the winning given a

conspicuously low level of importance. Figure 19.2 lists the principles that create more or

less healthy competitive contexts.

Figure 19.2 Distinguishing Healthier from Unhealthy Competition

In Healthy Competition

o The goal is primarily fun.

o The competitive goals is not valuable/real. And it is characterized

that way.

o The learning and/or growth goal is conspicuously characterized as

valuable.

o The competition has a short duration and is characterized by high

energy.

o There is no long-term effect from the episode.

o All individuals or groups see a reasonable change of winning.

o The students all firmly understand points 1-5 above.

o Examples include: Trivial contests, short-term competitions for a

solely symbolic reward, lighthearted challenges between groups

where there is no reward

In Unhealthy Competition

o It feels real. The winners and losers will be affected.

o The competitive goal/reward is valuable/real, and is characterized

that way.

o The learning task is characterized as a means to an end (winning the

competition).

o Winners are able to use their victory as social or educational capital at

a later time.

o Competition implicitly or explicitly rewards the advantaged students.

o Over time students develop an increasingly competitive mindset.

o Examples include: Long-term point systems, competition for grades,

grading on a curve, playing favorites, Awards for skill related

performance.

o

Chapter Reflection 19-f: Recall the last classroom competition that you observed.

Given the list above, would you classify it as a healthy or unhealthy competition?

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-5

What About a Little Bit of Competition for Meaningful Outcomes? Isnt it Okay

Sometimes?

It is highly likely that there are at this point readers who are thinking to themselves but I

use competition for meaningful outcomes and I dont see any problems with it. The

winners are happy and it seems like it makes the losers want to try harder so that they

can be winners in the future.

The full effect of an unhealthy competitive experience may not be apparent on the

surface or immediately. In fact, it may appear like it has had a rather desirable influence

on the students. Vockell (2004) points out that competition helps some students (i.e., the

winners) feel an enhanced sense of self-esteem by experiencing a favorable

comparison. That is, they feel better about themselves because they came out ahead of

someone else. One of the problems with this source of satisfaction is that it leads quickly

to the fear that in the future one may not come out on top - in other words, a fear of

failure. In fact, self-esteem based on comparison is not true self esteem (as discussed

in Chapter 8). It is a fragile ego construction. The best it can lead to is a temporary

experience of relief from feeling like a failure. Ultimately it leads to loss of intrinsic

motivation as a result of the student competing for the external reinforcement (i.e., the

prize, the validation, the favorable comparison) and defining themselves by their

personal win-loss record.

When the student sees his/her school performance as a contest, it leads increasingly to

what Dweck (2000) refers to as a helpless pattern. As discussed in Chapter 8, the

helpless pattern develops as a result of the student perceiving himself/herself as having

a fixed quantity of ability and therefore needing to prove that they are adequate relative

to others. While on the surface what may appear as students who are motivated to

perform, is more likely actually evidence of students motivated to avoid the pain of

feeling inadequate and inferior. The development of this helpless pattern promotes a

decrease in internal motivation, a decreased value for growth as a goal, and decreased

resilience to challenging situations. So initially we may see students who are energized

by the competitive challenge (out of fear of failure, or a desire to enhance their self

image by accomplishing a favorable comparison to others), however, we will eventually

get student who put in less and less effort on the task, quit when things get difficult, and

lose interest in learning unless it includes the drama that the competitive element brings

(i.e., much the same way that the gambling addict needs to play for money to be able to

take an interest in playing the game.)

Chapter Reflection 19-g: Reflect on the most desirable state of mind of those who need

to perform successfully in highly competitive situations. In some situations, in which the

contest is about brute strength, there are occasions when fear and anger can create a

desired effect. Yet, by and large competitive performance requires the execution of skills

and strategy. Take for example professional golf. When high performing players were

asked to explain what they were thinking in a given pressure situation, the most common

answer is that they were trying to keep their attention in the moment and resist the

temptation to attend to the external stimuli. But as we know, they are not always

successful in doing so. When a player does fail to stay in the moment and begins to shift

their thinking from each shot to an awareness of their performance relative to the others

on the course and/or relative to a negative event in their past, the common result is poor

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-6

play. Commonly this takes the form of a breakdown and/or what is referred to as

choking. The top performers such as Tiger Woods have learned to discipline their

minds to focus only on the moment and enjoy the process. They know that thinking in

terms of comparisons (i.e., competitively) will lead to less effective performance as well

as mental distress and less enjoyment of their job.

Classroom Applications of Competition

For what age levels is competition appropriate? The answer is that it is more appropriate

as students get more mature, but little or none of it is appropriate for very young

children. There is no real justification for using more than a minimal amount of

competition in the K-3 classroom. At this age it has no value or necessity. In the K-3

classroom, our task is to help students form a success psychology. Competition has

very little value in our efforts to do this and will much more likely work against this goal.

For grades 3-6 a small amount of healthy competition can be justified. Students at this

age are old enough to separate themselves from their outcomes within competitive

tasks, if we help and support them in doing so. Therefore a taste of healthy competition

in schools can help the intermediate age student make sense of and navigate the other

competitive contexts in which they may find themselves. After 7th grade, students are

mature enough to understand many of the natural tendencies, both healthy and

unhealthy, that will want to emerge from within them during the competitive context.

Therefore a reasonable amount of healthy competition, led by an adult who helps the

students remain intentional and aware can be justified from middle school on.

We might think of competition in the classroom as we do a timed or public performance

it raises the level of threat in a situation. When is that a good thing? Typically, when the

skill or knowledge being performed is well-formed and internalized and/or it is becoming

rusty. When is it a bad thing? When the students are still learning the skill and need to

put conscious attention into it. When one is learning a new skill he/she needs to have a

high support and low threat situation. It is only when we have mastered a skill or set of

knowledge that it is useful to test it in a competitive, timed, or publicly displayed context.

As we examine some common applications of competition in the classroom, we can see

that some would best be characterized as entirely unhealthy, while others can vary from

more to less healthy depending on how they are designed and led.

Grading on a Curve. Ever fewer teachers subscribe to the use of normative

grading (i.e., grading on a curve). This is an encouraging trend, as it is

difficult to find any support that it is motivational or necessary. Pitting one

student against another for grades has consistently been shown to have

serious ill-effects (Cropper, 1998; Lam, Yim, Law & Cheung, 2004; Kohn,

1986). Moreover, the amount of motivation that it does produce is rather

limited and less powerful than other social structures such as cooperation

(Johnson & Johnson, 1974, 1988).

Chapter Reflection 19-h: Have you ever blanked out in a competitive condition? When

the stakes have been high for a test or public performance, have you ever found yourself

forgetting what to do or say? Test anxiety is a byproduct of the competitive factor. Our

consciousness shifts from the task to the cost of the performance of the task and we

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-7

blank out. The creative mind has been shut down. What is left is a mental defense

responding to a threat condition. While this emotional response may be effective at

producing fight or flight chemicals in the body in the case where we must engage a crisis

of survival, it is not very useful when we are trying to think clearly and calmly. To test this

principle, consider how you performed the same task in a non-threatening context at

another time. Was your mind more at ease and thus more effective?

Playing favorites, Praise and Disappointment. It may not appear on the

surface to create a competitive condition, but when we give a differential level

of liking, personal praise (see Ch. 8), or its opposite - personal

disappointment, we are creating a subtle form of classroom competition. In a

sense, when we do this we are saying that there is some criteria that we use

to decide whom to show more affection and admiration. Showing differential

levels of liking will have the effect of essentially an emotional token economy.

All students lose in the long run in this kind of environment. While the

favorites may initially feel fortunate, however, along with those that have been

un-favored, they are being encouraged toward an external locus of control

and a failure psychology. Ultimately this type of competitive emotional climate

can be even more harmful than creating a competitive performance

environment.

Chapter Reflection 19.i Reflect on your experience as a student. Can you think of

teacher behaviors other than games and normative grading that caused you to think of

yourself as being in competition or to comparison of yourself in relation to the other

students in the class? What were they?

Table Points and Group-Group Competition for Points. In some cases,

using games that result in group points can be a useful tool to help bring a

heightened level of attention and importance to certain group skills and can

help clarify behavioral expectations. For example, during the first week of

school, we might give points to groups for being ready, listening,

demonstrating intra-group cooperation, exhibiting or going beyond the class

expectations, etc. As a result, this practice can fall in the healthy column, if it

is done thoughtfully and deliberately. However, beware of the pitfalls. Above

all be clear about what behavior leads to what outcome. Therefore, it is

important to make a clear distinction among the following: a) that which is

graded academically, b) that which is rewarded/graded for investment in the

process/participation, and c) that which is given points. Even if these

distinctions exist, they can be difficult for some students to interpret. So first,

we need to make sure that we keep these areas separate and distinct, and

second, be very clear and conspicuous with our students what system is

leading to what.. As discussed in Chapter 21, assessing participation and

process can be a very sound strategy. However, this assessment information

should never be used as part of a competition or a game. For example, if we

give group points for quality process investment and/or cooperation and then

include these assessments as part of a group grade for a project, we need to

keep those points separate from any points that we give for a group

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-8

competitive game. We can do both the game and the participation

assessment, however, we just need to keep them entirely separate. If not, we

can destroy the sense of reliability and trust in our formal participation

assessment system, and our game will be a lot less fun as students will be

confused about the purpose and impact. In Figure 19.3 a purposeful and

effective use of table points is contrasted to an accidental and ineffective

system.

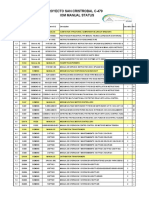

Figure 19.3: Comparison of a Healthy vs. Unhealthy Classroom Points Competition

System

Accidental/Unhealthy Use of Intentional/Healthy Use of Competition

Competition Group Table Points for Group Table Points

Teams are randomly selected and will be in Teams are selected to be representative and

place for a long period of time. evenly matched, and are changed every couple

days or weekly at the very latest.

A reward is given to the team that wins at the There is no talk of a reward. Teams are just

end of the competition that most students feel competing for abstract points.

is of real and meaningful value (i.e., a prize, a

party, a substantial privilege such as not having

to do an assignment (which is a

counterproductive reward in and of itself, as

discussed in ch.7).

The teacher gives points for performances The teacher gives points for a variety of things

where some students have an advantage, such that are often trivial, sometimes connected to

as intelligence, background knowledge, the content of the class, and frequently related

culturally biased knowledge, physical ability, to the demonstration of behavioral expectations

etc. (i.e., things over which students have complete

control). For example, when the teacher sees

one group cooperating effectively, they would

(without warning and only minimal recognition)

give that team a point. Conversely, when the

teacher observed a group or two that was

being selfish and making a poor effort

investment, they may give the other groups a

point who are making a quality effort. The

recognition is always on the positive. The

negative is only recognized as the absence of

valuable behavior.

The points are counted at the end of each day Once in a while the teacher points to the point

and the team who is in the lead is given a great totals, but puts most of their verbal energy into

deal of affirmation. The teams who are not in the improvement of the quality of the behavior

the lead are given a bit of shame for being in the class. The teacher helps the students

behind and any team who is far behind is recognize that their efforts to learn how to

teased. collectively function are paying off, to the

mutual benefit of the class.

Predictably there will be a team or two who will The competition is not held up as a substantive

be out of the running in the point standings, means to personal satisfaction for the students.

and they will be very aware of it. Predictably, So while they are interested in the outcome

they begin to blame and resent one another. As and feel a sense of drama, they do not feel

the competition goes on they will increasingly substantially attached to the outcome. The

lose interest in the game and begin to make teacher has been very intentional about helping

only a minimal effort or even possibly lose on them recognize the many other meaningful

purpose as a means to exerting a sense of outcomes that are taking place in the class that

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-9

power over the situation. They will increasingly are of importance, such as the individual and

grow in their resentment of the team that is collective growth of the class.

winning and the teacher.

The competition becomes a source of pain for The completion is changed and modified

the teams that are far behind as it drags on. frequently so it never gets stale and all teams

For the teams in the lead it is a source of a feel that they have a chance to come back and

feeling of entitlement, superiority, and fear of win. Since the teacher has never made a big

losing. . While it maintains some power to deal of winning, the team in the lead does not

modify behavior, this power decreases daily, fear losing what is essentially only a symbolic

and it is related primarily to a desire to avoid reward. After a couple of weeks the teacher

pain. ends the competitions.

Competition is used throughout the whole year Competition is brought back once in a while for

and the importance of it is increasingly brief episodes, but is never given any place of

emphasized. This is necessary because, while importance.

the students do not realize it, they are losing See the next section Competition in the

interest, because there is nothing inherently Transformative Classroom.

satisfying about the competition and the reward

is not worth being so slavish to the procedures.

Knowledge bowl, Trivia, Jeopardy and/or Mock Quiz Show Games. If we design

a game for our students to play that includes academic content, it has the potential

to be fun and help reinforce certain skills and content, however, we need to keep in

mind the principles for a healthy competition. For example, the use of a jeopardy-like

game, or a team knowledge bowl competition to review for tests can raise the level of

interest and excitement while accomplishing essentially the same degree of content

processing. But if the outcome of the game becomes part of what is formally graded,

the competition goes from the healthy to the unhealthy column. Let us compare two

scenarios, one in which the outcome translates into each students formal grade and

a more healthy application in which it does not.

In a healthy use scenario, we might divide the class into 4 groups and have students

work together to answer questions related to the content of any upcoming exam. The

content would be familiar and the competition would act as a means of testing the

degree to which the students could retrieve the information under pressure. The

purpose would be clearly stated as a form of preparation for an exam. At the end of

the competition the teacher would want to recognize the efforts of each team and ask

the teams to offer the winning team their congratulations and polite applause. After

this recognition of effort, it would be effective for us to make a statement related to

what the knowledge level during the competition indicated about the assessment of

readiness of the group. In this scenario, the competition is simply a means, the

desired end is the learning and the fun.

In an unhealthy scenario, the one might start the same way, by dividing the class into

4 groups. But as soon as we tell the class that the competition has a meaningful cost

(the grade for the day in this case), things will change. One of the first changes will

be that the students will become conspicuously obsessed with fairness, the rules and

the appearance of cheating and/or any sign of favoritism by the teacher. A great deal

of our energy will need to be spent putting down angry demonstrations when any

event is perceived by students to have been unfair. As discussed earlier, the

members of each team will be encouraged by the competitive structure to put aside a

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-10

democratic and egalitarian mentality and make judgments about how best to win.

Ones team members become seen less as participants in a learning activity and

become obstacles to achieving a valued outcome (winning). When the game is over,

it is likely that the students will walk away with the primary lessons learned being

related to the fairness of the game, the teachers responsibility for making the game

and the teams fair, and ultimately their degree of happiness or unhappiness related

to the outcome. What was learned about the content or group cooperation will likely

take on a much less meaningful significance. If we continue to use the same format,

these trends will become strengthened. Over time the students will begin to

associate us increasingly less with fun and more with the cause of their

dissatisfaction. The bickering and complaining will start as soon as the teams are

created. Moreover, the students will become increasingly impatient with low-ability

members of their teams. The hostility within those that are embarrassed during the

activity will likely come out in retribution in contexts other than the content review

game. Those that are resentful of losing, due to what they perceive as the

performance of the other members of their team, will grow in their dislike of those

they see as the cause of keeping them from obtaining the goal of a desirable daily

grade. In this scenario it is tempting to blame the level of character in the students,

when the real culprit is the structural design of the competitive activity itself.

Chapter Reflection 19-j: How would you feel at the end of a review activity if the

teacher gave daily grades depending on how well your team did? What would

change in your attitude the next time you played?

The Place of Competition in the Transformative Classroom

A thoughtful and intentional use of competition has its place in the transformative

classroom. Competitive contexts offer learning and growth opportunities that are unique.

The primary goal in the transformative classroom is to help students become familiar

with the feelings and tendencies that will want to emerge from within, and take a

thoughtful and intentional approach to their participation within the competitive context.

Teaching students how to deal with competition could be compared to sex education. In

doing so, we are not endorsing any behavior, but it assumes that the student may likely

find themselves in a situation where knowledge and a proactive mindset to this area

could be valuable, so they should have a healthy and informed approach to it.

In most cases, the competitive context brings out feelings in students that they think are

natural. In a sense, these feelings are natural, however, they are not going to lead to a

feeling of natural happiness and peace (i.e., the natural condition). Students should be

helped to see the feelings that competition brings out as normal and predicable, but not

necessary. Feelings such as worrying about losing, needing to win to feel good about

oneself, or needing the drama of the competition to feel interested, or being so worried

about the outcome that one losses focus on the process, are all normal but inevitably

dysfunctional habits of mind. We need to therefore help our students recognize these

normal tendencies and instead use more functional thinking to guide their choices and

define their state of mind during a competitive experience.

To accomplish this competition education, we need to incorporate three factors. First,

we need to make sure that all competitive contexts are healthy as defined by Figure

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-11

19.b. If we create unhealthy contexts (e.g., we get excited about or give meaningful

rewards to the winners or we place a great deal of emphasis on the outcome as being

what is important) we will create confusing messages to the students, and undermine

our results. Second, we need to help students be aware of their competitive feelings in

low stakes contexts. Third, we need to help our students test their ability to stay

conscious and intentional in higher stakes competitive situations.

Low stakes competition includes situations such as when we tell the students that we

are looking for a ready group, when students are engaged in doing group

presentations, or when we have them take part in small-scale competitive games. During

these low-threat competitive contexts we need to be clear about the purpose of the

competition (i.e., fun and learning, and not winning) and help students pay attention to

what is going on internally. When it comes to games we might be very direct, making the

statement to the class, If we can play these games for fun, we will keep playing them. If

we start worrying about who wins or loses, or we start doing sloppy work to be done first,

we need to stop doing them. If, as suggested in Chapter 6, we give minor privileges

(e.g., getting to go line up first) to groups or individuals for being ready early, we need

to make it clear that we all need to be ready, that it helps the whole class, and we are

just using the game to emphasize that an important collective skill. Our message to

students may be This is good practice for games in life, we are all capable of being the

first ones ready, if your group is ready first, great, if not, you made a good effort that

helps us all. So we all win when we try our best.

Chapter Reflection 19 k: Recall our discussion of the 1-Style Classroom in Chapter

12. If we are trying to help students become self directed, we may want to wean them off

behavioral expectation competitions such as looking for the ready group when we see

the behavior become internalized and consistently demonstrated. We can substitute

positive recognitions and then ultimately group appreciation and recognition as the class

develops as a community.

As we raise the level of competitive energy, we need to help the students keep in mind

that the reason that we are using the skills that we have developed in a competitive

context, is not to see who is better, but to see how well each of us does with a

competitive learning environment. We are primarily testing our characters, and only

secondarily testing our skills. We need to help them see that we are helping them learn

how to perform under pressure, and learn that one can actually perform in high stakes

contexts without the need to feel pressured, anxious, or like their self-esteem is attached

to the outcome.

As we help students grow in their understanding of how to take part in competition

without losing awareness of what will lead to the most intentional, functional and

productive outcome, we need to be very specific and pro-active in the messages that we

send and the consequences that we deliver. In each competitive situation, we might

keep in mind the following: a) potential problems that might come up, b) the messages

that we would want to send to resolve and bring awareness to those problems, and c)

the actions that we will take if we need to if, students cannot do it on their own.

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-12

Below are a few of the potential problems that may arise as students learn to be

effective within competitive contexts, some of the messages that we would want to send

as a result, and possible actions that we may need to take to help reinforce the

messages.

Potential Student Problem 1: We notice students being tentative and anxious

showing that they are working in part out of a fear of failure.

Intentional Teacher Counter-Message: When the students take on a mindset of a fear

of failure, we need to first bring their awareness to what they are thinking. We need to

ask them if they are working from a desire to grow and learn (i.e., a mastery orientation)

or a spending a lot of mental energy and attention on protecting their self-image (i.e., a

helpless orientation). We will want to remind them that we are playing for fun, and what

is important is what they learn. We need to tell them to stay in the moment, focus on the

process and let the outcome take care of itself.

Possible Teacher Action: First, we need to be sure that we can back up what we are

saying and the competition is not for meaningful stakes, the students are prepared for

what we are asking them to do, and the we have not created an emotional climate that

has glorified winning. Second, we need to send a message that we care about each

student and want them to do well. We need to be the teacher not the judge, let them see

us putting our attention into instruction, and supporting their efforts with that instruction.

Potential Student Problem 2: Students begin to put too much focus on the

outcome/winning and lose sight of quality, cooperation, process, sportsmanship, and

ethics, or become too concerned with fairness and cheating.

Intentional Teacher Counter-Message: When the students get too focused on the

competitive element of the task, remind them that what is important is what they learn

and how they treat one another. Remind them that the competition does not affect their

grade or anything else that is important. If they are obsessed with fairness, help them

use it as a means to becoming bigger than their situation. Explain to them that winners

overcome adversity and dont get sidetracked by bad calls, corrupt systems, bad breaks,

etc. Help them see that this is good practice for life. Real victory is the ability to look

back and like how we acted during the competition.

Possible Teacher Action It would be a good idea if your assessment system supported

the message that what is being rewarded in the class is the process. Chapter 21 may be

helpful in that area. If a team or individual does not show the ability to work in a

competitive context without falling apart emotionally, blaming, cheating, or complaining

excessively, a consequence is required. The best consequence in this case will most

often be losing the opportunity to take part. Having a group or student sit out and reflect

on their previous actions and the priorities that motivated them should be valuable. It

may help to reflect along with them, if they are having trouble seeing where they are

going wrong. But as always our message to them needs to be I know that you will be

able to do this eventually, relax, take a few deep breathes, think about it a while. During

this past situation you were not able to show the level of self-discipline that we need to

be able to take part. You are smart, capable and reflective, and you have a lot to

contribute, so lets work on this so you can join the group as soon as possible.

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-13

Potential Student Problem 3: Things get too heated and students become too

competitive and place too much value of winning. When this happens we can recognize

that students are trying to enhance their egos and defend their self-images by winning,

and while it is ultimately a never ending and losing battle, in this case the students have

lost perspective and are following unhealthy instincts.

Intentional Teacher Counter-Message: When things get heated that is a clear sign that

the students are letting their egos get too involved. We might begin by asking them a

question such as Hey gang, it is just a game remember? Ask yourself, what is it that is

making you so competitive right now, is it the need to feel good about yourself by beating

others or proving your worth? Look around, these are your friends, they will still love you

and you will still love yourself when the game is over. Help them stay in the moment and

enjoy the process and recognize that peak performance comes from being completely in

the moment and letting go of the outcome. Help them shift their goal to staying present

and doing a good job with the quality of the relationships and performing the task, and

away from the illusion that wanting to win will help you win and/or be happy and

satisfied.

Possible Teacher Action: If the students cannot hear your redirection message

because they are too immersed in the drama of trying to enhance their self-images by

winning, you will need to simply withdraw the privilege of the competition. Our message

to them at this point, will need to be that in this class, we compete to learn how to

compete, when we cannot demonstrate that we are ready for it, we need to stop for a

time and then try again when we are. When the emotions are still fresh, an episode

such as this may provide a powerful opportunity for the class to reflect on why it is so

difficult for any of us not to get all tied-up in needing to win. However, if we have allowed

the game to come to completion, this processing will not be as powerful. We need to let

the class recognize the clear cause and effect significance in our action in this class

we use competition to the degree that we are ready for it.

In the transformative classroom, the feedback and positive recognitions are reserved

entirely for process related performance and the quality of the participation. In the

transformative class students learn that winning is not the point, and losing is not a big

deal. Neither winning nor losing is meaningful. What is meaningful is what we learn

about ourselves in the process, how we treat each other, what we learn about our skill

level.

Chapter Reflection 19-l: Reflect on your role as the teacher/leader in the transformative

class. While we may need to provide strong guidance and leadership as the group is

learning to function, our goal should remain to let them learn to do it themselves. So

avoid being in the role of referee or judge. Can you think of a teacher that you have seen

that liked to be in the role of referee? What did the students learn as a result? Where did

the anger and complains go when things went wrong?

Finally, we need to remember that, in the transformative class, games are for fun. In the

transformative classroom games and competition provide both a learning opportunity

and a chance to play. So what makes a game fun? First when the participants do not

fear the potential consequences. So teaching students how to play without fear of failure

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-14

or letting their egos become too involved is prerequisite. Second, students need to

access the joy of the moment and have fun with the process. Involvement, challenge,

adventure, suspense all can feel fun, if the student lets themselves and the situation

supports fun over comparison. The influence of comparison will be a fun killer. Fun

during a competitive context occurs when the participant sees the competition as the

game, and the fleeting reality, and the learning, relationships, and self-respect as the

lasting reality.

Conclusion

So we must approach the use of competition like it is toxic paint or an electric power tool.

It can produce beautiful results, but unless we take great precautions the likelihood is

that we will regret putting it in the hands of young people. If it seems harmless, it is

simply because we are not perceiving the threat clearly. And while no one is going to sue

us for promoting a fear of failure like they would if we allowed a student to injure

themselves with a power tool, we need to be no less safely conscious.

In the next chapter, we will examine the sibling of unhealthy competition - the use

systematic public shaming in the form of a deficit model behavioral system. In much the

same way as competition can motivate by fear of failure, deficit models motivate by a

fear of experiencing guilt and shame. In Chapter 21, we examine more healthy

alternative that achieves both more effective results as well as supports our efforts to

promote a success psychology within our students.

Chapter Reflections

1. Reflect on your experience as a student. What was your experience of

competition? Do you still hold that perception today? Do it affect the way that you

approach competition in your classroom?

2. What types of teacher behaviors encourage students to think competitively? Can

you think of teachers that you have observed that promoted a mentality of

comparison and competition among their students in ways other than games and

contexts?

Chapter Activities

1. In your group, discuss the question Is the real world competitive? Can one live a

competition free life?

2. For each of the following activities conceive of teacher behavior and/or a lesson

design structure that would promote it being a healthy competition, and one that would

promote it being an unhealthy competition.

a. Reporting the results of a test.

b. Walking through the room examining student projects.

c. Encouraging groups to clean up and get ready.

d. Holding a Spelling Contest

e. Holding a food drive

References

Cropper. C. (1998) Is Competition an Effective Classroom Tool for the Gifted Student?

Gifted Child Today Magazine, v21 n3 p28-31 May-Jun 1998

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-15

DeVries, D., Edwards, K., & Wells, E. (1974). Team competition effects on classroom

group process (Tech. Rep. No. 174). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, Center for

Social Organization of Schools.

Dweck, C. (2000) Self-Theories; Their Role in Motivation, Personality and Development.

Psychologists Press.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1974). Instructional goal structure: Cooperative,

competition, or individualistic. Review of Educational Research, 44, 213-240.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1989). Cooperation and competition: theory and

research. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative,

competitive, and individualistic learning. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kohn. A. (1986) No Contest: The Case Against Competition. Houghton Mifflin

Lam, S., Law, J., Cheung, R. (2004) The effects of competition on achievement

motivation in Chinese classrooms. British Journal of Educational Psychology, June pp.

281-296(16)

Vockell. E. (2004). Educational psychology: a practical approach. Purdue University.

http://education.calumet.purdue.edu/Vockell/EdPsyBook/

Webster (2007) New World Dictionary: Online.

Transformative Classroom Management J. Shindler do not reproduce 19-16

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Rules of the Race: The Power of Competitive Strategy to Shape Business SuccessDa EverandThe Rules of the Race: The Power of Competitive Strategy to Shape Business SuccessNessuna valutazione finora

- Cooperation, Competition & Individual Effort - 1st SessionDocumento16 pagineCooperation, Competition & Individual Effort - 1st SessionQDWQWNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 5Documento19 pagineCH 5omahachemNessuna valutazione finora

- Highly Competitive EnvironmentDocumento3 pagineHighly Competitive EnvironmentMadina BayNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical Paper-A2Documento10 pagineTechnical Paper-A2api-178275861Nessuna valutazione finora

- Technical Paper-A2Documento10 pagineTechnical Paper-A2api-273400826Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation Ready For BindingDocumento68 pagineDissertation Ready For BindingTunji OkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Interdependence QuestionsDocumento3 pagineInterdependence QuestionsLinh DalanginNessuna valutazione finora

- BSZ IM Ch01 4eDocumento10 pagineBSZ IM Ch01 4eCurtis BrosephNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Management Skills 9th Edition Whetten Test BankDocumento34 pagineDeveloping Management Skills 9th Edition Whetten Test Banksoojeebeautied9gz3h100% (10)

- Group Dynamics (Ii Mba) : Group vs. Individual Performance AppraisalsDocumento17 pagineGroup Dynamics (Ii Mba) : Group vs. Individual Performance AppraisalsV.R BhuvaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Allama Iqbalopenuniversity, Islamabad (Commonwealth MBA/MPA Programme)Documento6 pagineAllama Iqbalopenuniversity, Islamabad (Commonwealth MBA/MPA Programme)Faisal KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Strategies-ACTIVITYDocumento3 pagineReading Strategies-ACTIVITYDiana Mamaril100% (1)

- OB Mid SemDocumento6 pagineOB Mid Semprajakta kasekarNessuna valutazione finora

- Competition and CooperationDocumento22 pagineCompetition and Cooperationshane_anthonyNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.5 A Conflict ManagementDocumento17 pagine1.5 A Conflict ManagementChitra SingarajuNessuna valutazione finora

- Nahzatul Shima Binti Abu Sahid Namaf5A 2022519651Documento7 pagineNahzatul Shima Binti Abu Sahid Namaf5A 2022519651Izatul ShimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Solutions Manual 1Documento36 pagineOrganizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Solutions Manual 1jenniferjensencdjpkfbyag100% (23)

- Organizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Solutions Manual 1Documento33 pagineOrganizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Solutions Manual 1toby100% (50)

- CHAPTER 14 HUMBOR Conflict and Negotiations in Organizations 1Documento27 pagineCHAPTER 14 HUMBOR Conflict and Negotiations in Organizations 1Lannie Mae SamayangNessuna valutazione finora

- Case StudyDocumento6 pagineCase StudyRim ChtiouiNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion Assignments - Term 1Documento16 pagineDiscussion Assignments - Term 1eme.ogbonna1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Project and Flipped ClassesDocumento9 pagineProject and Flipped ClassesOmar ArroyoNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The Best Essay Writing ServiceDocumento8 pagineWhat Is The Best Essay Writing Serviceb7263nq2Nessuna valutazione finora

- El - Module 3 PrefinalDocumento11 pagineEl - Module 3 PrefinalJhon Carlo GonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Reference: Focus On Teaching 221Documento8 pagineReference: Focus On Teaching 221Ami KapasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Question 1Documento3 pagineQuestion 1blablablaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership & Team EffectivenessDocumento29 pagineLeadership & Team Effectivenessshailendersingh74100% (1)

- Student Queries Relating To The Upcoming MP Exam 100123 To 130123Documento10 pagineStudent Queries Relating To The Upcoming MP Exam 100123 To 130123ashirwad modiNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Measure Training Effectiveness: Home Our News and ArticlesDocumento7 pagineHow To Measure Training Effectiveness: Home Our News and Articlesanon_175099681Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective EvaluationDocumento8 pagineReflective Evaluationanam khalidNessuna valutazione finora

- Course: Organizational Behvavior Topic Title: AssignmentDocumento10 pagineCourse: Organizational Behvavior Topic Title: AssignmentI AbramNessuna valutazione finora

- Masters Programmes: Assignment Cover SheetDocumento6 pagineMasters Programmes: Assignment Cover SheetBelle TanyapornNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay ConclusionsDocumento5 pagineEssay Conclusionsezksennx100% (2)

- Strategic Business AnalysisDocumento9 pagineStrategic Business AnalysisKrishaciara CrisostomoNessuna valutazione finora

- MGT AssignmentDocumento3 pagineMGT AssignmentHaidar Hossain RahadNessuna valutazione finora

- Gujarat Technological UniversityDocumento12 pagineGujarat Technological UniversityBhavya PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- LDR 531 Final Exam Latest UOP Final Exam Questions With AnswersDocumento8 pagineLDR 531 Final Exam Latest UOP Final Exam Questions With AnswersEmma jons100% (1)

- Policy Chap 8Documento8 paginePolicy Chap 8matten yahyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Belonging Story ReviewDocumento4 pagineBelonging Story ReviewMuskan TanwarNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective ReportDocumento8 pagineReflective ReportAimenWajeehNessuna valutazione finora

- ADL 05 Organisational Behavior V2Documento19 pagineADL 05 Organisational Behavior V2Sachin ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 8 Workforce Economic and AnalyticsDocumento5 pagineWeek 8 Workforce Economic and AnalyticsRetemoi CookNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics Naturalist EssayDocumento3 pagineEconomics Naturalist EssayJosh Cody OngNessuna valutazione finora

- CPD 26612Documento12 pagineCPD 26612steveokaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Group Dynamics Research PaperDocumento4 pagineGroup Dynamics Research Paperafedpmqgr100% (1)

- Term Paper On Group DynamicsDocumento4 pagineTerm Paper On Group Dynamicsafdtywgdu100% (1)

- Mfocs DissertationDocumento6 pagineMfocs DissertationWriteMySociologyPaperCanada100% (1)

- Week 9 - Option 1 - PlayshopDocumento6 pagineWeek 9 - Option 1 - Playshopamanda bahia pintoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper On Students MotivationDocumento8 pagineResearch Paper On Students Motivationwwvmdfvkg100% (1)

- ВВЕДЕНИЕ В ОРГАНИЗАЦИОННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ - ГЕНКИН - ENGLDocumento142 pagineВВЕДЕНИЕ В ОРГАНИЗАЦИОННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ - ГЕНКИН - ENGLEugGueNessuna valutazione finora

- College Athletes Should Get Paid EssayDocumento4 pagineCollege Athletes Should Get Paid Essayohhxiwwhd100% (2)

- Advantages and Disadvantages of CompetitDocumento2 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of CompetitNoor Ul HudaNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Competit PDFDocumento2 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of Competit PDFDindamilenia HardiyasantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Exam - CosicoDocumento5 pagineFinal Exam - CosicoAIRA NINA COSICONessuna valutazione finora

- There Are Seven Motivational StrategiesDocumento5 pagineThere Are Seven Motivational StrategieshemantnalekarNessuna valutazione finora

- Theory of PerformanceDocumento4 pagineTheory of PerformanceRandi Eka Putra100% (1)

- Ogl 220 Module 6 WorksheetDocumento4 pagineOgl 220 Module 6 Worksheetapi-672516350Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Tay Son Uprising - George Dutton (2006) PDFDocumento307 pagineThe Tay Son Uprising - George Dutton (2006) PDFChinh Xuan100% (2)

- Shareholder Wealth Maximization - Theory & Critique: 1. TitleDocumento4 pagineShareholder Wealth Maximization - Theory & Critique: 1. TitleChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- SWM - Concept & Critiques PDFDocumento14 pagineSWM - Concept & Critiques PDFChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Thought Final Print Book 3Documento534 pagineHistory of Thought Final Print Book 3Syed Yusuf SaadatNessuna valutazione finora

- FECO Note 2 - Simple Linear Regression: Xuan Chinh MaiDocumento7 pagineFECO Note 2 - Simple Linear Regression: Xuan Chinh MaiChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Democracy in America Vol 2Documento425 pagineDemocracy in America Vol 2Cosmin AlexandruNessuna valutazione finora

- 1994 - Colegrave - Game Theory Models of Competition in Closed SystemDocumento8 pagine1994 - Colegrave - Game Theory Models of Competition in Closed SystemChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- DraftDocumento3 pagineDraftChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- FECO Note 1 - Review of Statistics: Xuan Chinh MaiDocumento13 pagineFECO Note 1 - Review of Statistics: Xuan Chinh MaiChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dumb Luck Vu Trong Phung PDFDocumento193 pagineDumb Luck Vu Trong Phung PDFChinh Xuan88% (8)

- BEBE - Experimental Critique Part IDocumento16 pagineBEBE - Experimental Critique Part IChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Announcement of WUS ScholarshipDocumento1 paginaAnnouncement of WUS ScholarshipChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- EP 1.0 New Gear List Ver 2.0 - Upgradeable GearsDocumento9 pagineEP 1.0 New Gear List Ver 2.0 - Upgradeable GearsChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1: Economic Questions and DataDocumento6 pagineChapter 1: Economic Questions and DataChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 7: Serial EntrepreneurshipDocumento1 paginaTopic 7: Serial EntrepreneurshipChinh XuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Should I Hire You - Interview QuestionsDocumento12 pagineWhy Should I Hire You - Interview QuestionsMadhu Mahesh Raj100% (1)

- StrategiesDocumento7 pagineStrategiesEdmar PaguiriganNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Architecture VI: Unit 1Documento20 pagineHistory of Architecture VI: Unit 1Srehari100% (1)

- Profix SS: Product InformationDocumento4 pagineProfix SS: Product InformationRiyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Molecular Biology - WikipediaDocumento9 pagineMolecular Biology - WikipediaLizbethNessuna valutazione finora

- Rectification of Errors Accounting Workbooks Zaheer SwatiDocumento6 pagineRectification of Errors Accounting Workbooks Zaheer SwatiZaheer SwatiNessuna valutazione finora

- CDS11412 M142 Toyota GR Yaris Plug-In ECU KitDocumento19 pagineCDS11412 M142 Toyota GR Yaris Plug-In ECU KitVitor SegniniNessuna valutazione finora

- Rock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary SedimentaryDocumento8 pagineRock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary Sedimentarymeletiou stamatiosNessuna valutazione finora

- TAX Report WireframeDocumento13 pagineTAX Report WireframeHare KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- FAR09 Biological Assets - With AnswerDocumento9 pagineFAR09 Biological Assets - With AnswerAJ Cresmundo50% (4)

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusDocumento18 pagineProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- Building Envelop Design GuidDocumento195 pagineBuilding Envelop Design GuidCarlos Iriondo100% (1)

- CLEMENTE CALDE vs. THE COURT OF APPEALSDocumento1 paginaCLEMENTE CALDE vs. THE COURT OF APPEALSDanyNessuna valutazione finora

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocumento6 pagineNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentJasmine KumariNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento2 pagineUntitledRoger GutierrezNessuna valutazione finora

- What's More: Quarter 2 - Module 7: Deferred AnnuityDocumento4 pagineWhat's More: Quarter 2 - Module 7: Deferred AnnuityChelsea NicoleNessuna valutazione finora

- Geotech Report, ZHB010Documento17 pagineGeotech Report, ZHB010A.K.M Shafiq MondolNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study GingerDocumento2 pagineCase Study Gingersohagdas0% (1)

- Conformity Observation Paper 1Documento5 pagineConformity Observation Paper 1api-524267960Nessuna valutazione finora

- Media Planning Is Generally The Task of A Media Agency and Entails Finding The Most Appropriate Media Platforms For A ClientDocumento11 pagineMedia Planning Is Generally The Task of A Media Agency and Entails Finding The Most Appropriate Media Platforms For A ClientDaxesh Kumar BarotNessuna valutazione finora

- Campos V BPI (Civil Procedure)Documento2 pagineCampos V BPI (Civil Procedure)AngeliNessuna valutazione finora

- High-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Documento7 pagineHigh-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Dongxi LvNessuna valutazione finora

- Hotel BookingDocumento1 paginaHotel BookingJagjeet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Sokkia GRX3Documento4 pagineSokkia GRX3Muhammad Afran TitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Right To Freedom From Torture in NepalDocumento323 pagineRight To Freedom From Torture in NepalAnanta ChaliseNessuna valutazione finora

- The Normal Distribution and Sampling Distributions: PSYC 545Documento38 pagineThe Normal Distribution and Sampling Distributions: PSYC 545Bogdan TanasoiuNessuna valutazione finora

- STD 4 Maths Half Yearly Revision Ws - 3 Visualising 3D ShapesDocumento8 pagineSTD 4 Maths Half Yearly Revision Ws - 3 Visualising 3D ShapessagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Health Services-1Documento44 pagineChild Health Services-1francisNessuna valutazione finora

- Before The Hon'Ble High Court of Tapovast: 10 Rgnul National Moot Court Competition, 2022Documento41 pagineBefore The Hon'Ble High Court of Tapovast: 10 Rgnul National Moot Court Competition, 2022sagar jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Fort St. John 108 Street & Alaska Highway IntersectionDocumento86 pagineFort St. John 108 Street & Alaska Highway IntersectionAlaskaHighwayNewsNessuna valutazione finora