Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

War Rugs PDF

Caricato da

Julian derenTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

War Rugs PDF

Caricato da

Julian derenCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Instructional Resources

War

Rugs:

Woven

Documents

of Conflict

and Hope

William Charland

Recommended for Grades 6-12

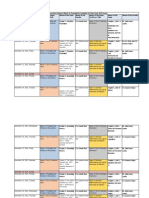

Figure 1. Subtle martial imagery

(Baluch style). Collection of author.

Photo: W. Charland.

November 2011 / Art Education 25

E

xposed to images of violence

and conflict around the

world, many students under-

stand such struggles only through

brief news clips and sound bites.

By providing an introduction to the

history, design, and production of War Rugs: An Introduction

Afghan war rugs, this Instructional War rugs (see Figures 1 and 2) are hand-made The Socio-Political Context

Resource is intended to help woven commodities produced in the rural of Afghan War Rugs

students pause and consider the villages and urban workshops of Afghanistan, The invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet

context within which individuals as well as crowded refugee camps in Iran and Union in 1979 followed internal unrest

turn to ages-old cultural practices Pakistan. Graphic and visually striking, war in the Afghan government (Maley, 2009).

rugs are marketed globally, available on the Afghanistans communist party, upon seizing

to maintain a sense of continuity street corners of New York and other major

as war indelibly alters the world control in 1978, turned to the Soviet Union

cities, and in the virtual markets of eBay for support, alienating large portions of the

around them. These pedagogical and other online sites. War rugs are afforded countrys traditional Islamic population.

strategies are intended for middle- exhibition space in museums and galleries An Islamic insurgency formed to drive the

school and high-school students across the United States and Europe, and communists from power. Fearing the loss of

discussed in scholarly books, journals, and influence in the region, Soviet leaders quickly

who have achieved a certain museum publications (Allen, 2011; Cooke &

level of intellectual and affective overthrew the Afghan government and

MacDowell, 2005; Kuryluk, 1989; Mascelloni, replaced it with a more reliable subordinate

maturity. 2009). They range in quality from tightly government (Kakar, 1995), simultaneously

knotted intricate works of subtle coloration flooding Afghanistan with troops to quash

Learning objectives include: and meticulous craftsmanship to simpler, the determined resistance efforts of Afghan

Analyzing and interpreting war rugs; roughly constructed works dashed off for Muslim groups.

Exploring the subjectivity of seeing, quick sale.

However, the resistance to the Soviet

interpreting, and evaluating; invasion was nationwide (Kakar, 1995,

Recognizing constancy and change War Textiles

p.79). Afghanistans 250,000 square miles

in cultural expression; War is a defining activity in the history of

of topographical contrasts made modern

societies, and thus provides a key theme

Examining gender roles and the warfare difficult for the invaders. While

for artists and writers through the ages. In

reconfiguration of gender expectations; Soviet vehicles ground down in sand and

Homers Iliad, Helen of Troy is described

Investigating related work by dust, Afghan resistance fighters struck with

weaving the story of the war (Pantelia,

contemporary artists; and hit-and-run skirmishes, and found refuge in

1993, p.495) between the Trojans and the

rugged mountains and valleys. The weaponry

Exploring the role of creativity as a Achaeans. The war ships and battlefields,

employed by both sidesautomatic rifles,

universal coping mechanism. hails of arrows and crowds of warriors, the

rocket-propelled grenade launchers, missiles,

supine dead and dying that constitute the

fighter planes, helicopters, tanks, and

Bayeux Tapestry, probably commissioned in

personnel carriersare depicted in war rugs

the 1070s, speak of the Norman conquest of

(see Figures 1 and 2). During the conflict,

England in the Middle Ages (Lewis, 1999).

more than 5 million Afghans fled their

Textiles with war themes generally occur in

homeland, most of these to the relative safety

societies where the production of cloth is

of surrounding nations (Maley, 2009).

already a pervasive medium of deep cultural

significance (Cooke, 2005a, p. 9), and are The Taliban, a militant fundamentalist group,

nearly always created by women. In addition moved to assume control of Afghanistan.

to Afghan war rugs, examples of textiles that Soon after the September 11, 2001, attacks

document conflict are found among Hmong on New York City and Washington, DC, the

story cloths, Asafo flags, Haitian hunger US demanded the Taliban turn over leaders

cloths, Chilean arpilleras, Kuna molas, and of the group claiming responsibility for these

other artworks depicting the modern world attacks (al-Qaeda), who were believed to be

through a prism of traditional culture. seeking refuge in Afghanistan. The Taliban

refused, and the US (with British support)

commenced bombing Taliban strongholds

in Afghanistan, eventually handing over

command of the military security forces

to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO) in 2003.

26 Art Education / November 2011

Instructional Resources

Figure 2. Red rug, obvious imagery (Turkman style). Collection of author. Photo: W. Charland.

November 2011 / Art Education 27

Figure 3. Traditional boteh form (left) as basis for grenade images. Photo: W. Charland.

Although Afghanistan has witnessed figurative representation (Mascelloni,

the approval of a new constitution, the 2009) and narrative content. Images range

seating of the first democratically elected from flattened, highly geometricized, and

leader, and the training of a national army, abstracted forms (see Figure 1), to simpli-

conflict continues. The civilian population fied but recognizable representations (see

of Afghanistan continues to suffer hard- Figure 2), as well as pictures and maps

ships and casualties, while many millions detailed enough to distinguish specific

wait out the war in refugee camps (British battles, individuals, and weapons (Cooke,

By comparing early Broadcasting Corporation, 2009; Public

Broadcasting Service, 2008).

2005b, p. 59).

As the technique of weaving is built upon

impressions with later Cultural Adaptations

an x/y axis of vertical warp and horizontal

weft threads, certain shapes are more easily

knowledge, students War rugs are created by survivor-artists

driven by the twin needs of subsistence and

created than others. Straight lines are more

readily woven than curves, and the edges of

come to understand how self-expression (Cooke, 2005a, p. 24). Rug

weavers from Baluch, Turkmen, and Hazara

diagonal lines and circles appear stepped,

much as they do in a magnification of pixels

interpretations of art tribes (Cooke, 2005a) fled to refugee camps

in Iran and Pakistan. There they shared

in a digital image. This repertoire of simpli-

fied and geometricized forms allows artists

can develop and grow. experiences, skills, and visual motifs, thus

synthesizing distinct tribal styles (Hawley,

to adapt existing motifs to new purposes

by applying a few simple changes. Thus a

1970) into a new, broader Afghani aesthetic. boteh form (known in the West as a paisley)

Deprived of traditional means of earning a becomes a hand grenade (see Figure 3).

living, men resorted to weaving, an expres- A row of decorative diamonds in a gl, a

sive and economic venue previously the prominent Turkmen ornament, shifts into

domain of women (Mascelloni, 2009). the tread of a tank (see Figure 4), and stars

While the evolution of the war rug is not and flowers are reinterpreted as explosions

clearly delineated, modern weapons were (see Figure 2).

seen in Afghan rugs produced in the

Baluchistan region beginning in the 1930s. Formal Analysis vs. Lived Experience

Examples of weaponry as visual motifs that When presenting eye-catching works, a risk

appear prior to the Soviet invasion refute exists of inadvertently deemphasizing the

the notion that traditional weavers were challenges, setbacks, and triumphs of the

simply documenting the war around them. artists daily lives within war-torn envi-

Instead, they replaced the dragons, goats, ronments. No discussion of the conflicts

peacocks, and other symbols of prosperity, wracking Afghanistan can capture the

pride, and protection with depictions of depth and range of human emotions felt by

weaponry and mechanized war in a natural the weavers. Images on the rugs, reducing

process of modernization (Mascelloni, killing machines into pleasing patterns of

2009). soft wool, may inure the viewer and lead

to facile misinterpretations. We may begin

Repurposing Traditional to approach an understanding of the fear,

Design Elements grief, bravery, and persistence experi-

The composition of war rugs is based enced by Afghan weavers by listening to

on axial symmetry, a characteristic of their stories in their own words (Cooke &

traditional Afghan rug design, although MacDowell, 2005; Lessing, 1987).

some weavers employ Persian-influenced

28 Art Education / November 2011

Instructional Resources

Pedagogical Strategies: Research and Discussion

T he evocative images depicted on

war rugs capture the attention of the

viewer. The challenge in the classroom is to

Analyzing and Interpreting War Rugs

Prior to sharing information with your

class, allow students to view and analyze

Paraphrasing comments, the teacher asks

What more can we find?, throwing the

discussion open to another cycle of obser-

gradually move past immediate percep- a war rug using the technique of Visual vations and interpretations that build upon

tions to explore broader issues. To facilitate Thinking Strategies (VTS).1 Based on previous responses.

students journeys from fascination to research in aesthetic development (Housen, Explain to students how an anthropologist

deeper understandings, it is essential that 2002), a VTS session begins with a moment or art historian might initially approach an

students are provided with open-ended of quiet observation of a work of art, item of material culture in a similar way.

study that contextualizes war rugs and followed by the teacher asking, Whats Asking these types of questions provide

explores the art, the artists, and the culture going on in this picture? From that point researchers with frameworks for subse-

of Afghanistan. The following strategies on, students do most of the talking, while quent exploration, revealing information

guide students from subjective to increas- the teachers role is that of non-judgmental that leads to new understandings.

ingly objective understandings. facilitator. The teacher follows a students

observation with the query What do you Exploring Variability in Seeing,

see that makes you say that?, prompting Interpreting, and Evaluating

students to provide reasons and support. To demonstrate how ones understanding

of a work of art can change over time, ask

students to write about a war rug at the

beginning of a unit, and again at its conclu-

sion. By comparing early impressions

with later knowledge, students come to

understand how interpretations of art can

develop and grow. The three VTS questions

illustrated earlier are particularly effective

as prompts for student writing exercises.

To illustrate how the meaning of a work

of art can vary among viewers, share and

discuss excerpts from literature on seeing

(Berger, 1972; Wolcott, 2008), under-

standing (Belenky, 1986), and valuing works

of art (Karp & Lavine, 1991). Ask students

about instances when their own artwork

was misinterpreted by peers, teachers, or

parents/guardians. As a creative applica-

tion, ask students to role-play. How might

a female weaver, a male weaver, a rug

merchant, a collector, or a museum curator

describe her/his relationship with a war rug?

Comparing Constancy and

Transition in Cultural Expression

Have students list differences between

their generations styles and language, and

those of their parents/guardians. Share

and discuss these differences, working to

determine how generational styles occur.

Next, view an image of a decorative or

utilitarian (non-war) Afghan rug beside

an image of a war rug2 such as that shown

in Figure 1. Ask students to find motifs

and forms common to both, and identify

elements possibly originating in traditional

rug design.

Figure 4. Tank treads (top) derived from traditional gl form. Photo: W. Charland.

November 2011 / Art Education 29

Figure 5. Chicago

artist Barbara Koenen

creating war rug

installation. Photo

courtesy of artist.

Investigating Gender, the Arts, collections. These facts may help explain the

and Contextual Change male stereotype of an artist.

Have students close their eyes and picture a The story of the artists who create war rugs

Through strategies designed typical artist at work, and then quickly write exemplifies how environmental change can

a description of the artist. Sharing descrip- revalue or reconfigure gender expectations.

to expose students to the tions, note how often the artist is imagined Just as men began knotting rugs in Afghan

as male, and how often as female. In many refugee camps, women in the US assumed

persistence of art in even classrooms, this exercise reveals a stereotype, positions in business and manufacturing

a bias toward thinking of an artist as male. previously dominated by men during World

the most challenging Ask students why this gender expectation War II. In both cases, social eventsthe

occurs. existential threat of warallowed deeply

situations, we help them Ask students to draw a circle and divide it ingrained understandings of gender roles

and expectations to become suspended or

see the world through into a simple two-portion pie chart, writing

in one portion the percentage of males artists transformed.

anothers perspective, and and in the other portion the percentage of

female artists they think currently work Making Relevant

Contemporary Connections

facilitate their development in the United States. The sum of the two

percentages should add up to 100%. Do their If at all possible, arrange a visit to your

school by an Afghan artist to relate first-hand

as learners, artists, and pie charts match the results of the artist-

stereotype exercise? Reveal statistics from knowledge about their homeland, life, and

modes of visual expression. Lacking this

informed citizens. the recent census, which shows that slightly

more than half (52.4 %) of professional resource, have students explore the work

artists and designers in the US are women of contemporary Afghani artists3 online.

(U.S. Department of Labor, 2010). You may For example, an interview with Lida Abdul,

want to follow this with data published whose videos and performances deal with

by the Guerrilla Girls (1995) quantifying issues and images similar to those in war

gender inequities in museum exhibitions and rugs, is available courtesy of the Indianapolis

Museum of Art.4

30 Art Education / November 2011

Instructional Resources

Figure 6. Margi Weir. Childs Play, 2007. Digital inkjet print on rag paper. 12 x 18. Photo: M. Weir.

A number of US artists create works that Tech, the tapestry-like motif and juxtaposi- Conclusion

pay tribute to war rugs. Barbara Koenen,5 tion of mundane and violent iconography

a Chicago artist and activist, creates tempo- recalls elements of the war rugs, and repre- We teach art for many reasons, not the least

rary installations and prints based on war sents the idea of children shooting children of which is to broaden students under-

rugs (see Figure 5). To create her fragrant in a civilization overflowing with guns (M. standing of, and empathy toward, the human

rugs, she sifts powdered spices and seeds Weir, in personal correspondence with the condition in its diverse forms. This instruc-

through templates, delineating the edges with author, February 2, 2011). Ask students to tional resource employs images of weapons

fringes and firecrackers. To document these consider why an image such as Childs Play and conflict, which are often censored from

ephemeral works, Koenen lays prepared may be acceptable in an art gallery, but the art curriculum, as a basis for cognitive,

paper over the installation and gently lifts perhaps not in the hallway of a school. aesthetic, and affective growth. Through

it off, adhering the powdered materials to strategies designed to expose students to the

the papers surface. Several monoprints Assessment persistence of art in even the most chal-

are pulled from a single installation, each lenging situations, we help them see the

These pedagogical strategies focus on under-

successive state appearing increasingly faint world through anothers perspective, and

standing and appreciating war rugs, the

and fragile. facilitate their development as learners,

motivations of the artists who create them,

artists, and informed citizens.

There is a formal connection to war-rug and the context in which they are created.

imagery in Margi Weirs print Childs Play They call for authentic assessment methods

(2007), showing children engaged in play- to measure students ability to describe, William Charland is Assistant Professor of

ground activity (see Figure 6). Weir designs define, and reflect. Whether assessing the Art/Art Education at the Frostic School of

digital compositions of appealing patterns whole group, a small group, or individual Art at Western Michigan University.

that, upon careful viewing, reveal darker students, teachers can track learning by E-mail: william.charland@wmich.edu

underlying messages. The frolicking figures looking at levels of engagement, participa-

in this print are circumscribed by a border tion in discussions and exercises, clarity

of handguns, while the ghostly image of a of thought and expression, the ability to

young person pointing two guns, paramili- arrive at novel insights, and the capacity to

tary style, looms in the center. Inspired by empathize.

the massacres at Columbine and Virginia

November 2011 / Art Education 31

References

Allen, M. (2011). Battleground: War Cooke, A., & MacDowell, M. (Eds.). Maley, W. (2009). The Afghanistan

rugs from Afghanistan. Textile (2005). Weavings of war: Fabrics wars. (2nd Ed.). Basingstoke, UK:

Museum of Canada. Retrieved of memory. East Lansing, MI: Palgrave Macmillan.

from www.textilemuseum.ca/ Michigan State University Mascelloni, E. (2009). War rugs: The

apps/index.cfm?page=exhibition. Museum Press. nightmare of modernism. Milan,

detail&exhId=271 Guerrilla Girls. (1995). Confessions of Italy: Skira.

Belenky, M. (1986). Womens ways of the Guerrilla Girls. New York, NY: Pantelia, M. (1993). Spinning and

knowing: The development of self, Harper Perennial. weaving: Ideas of domestic order

voice and mind. New York, NY: Hawley, W. (1970). Oriental rugs; in Homer. The American Journal of

Basic Books. Antique and modern. New York, Philology, 114(4), 493-501.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. NY: Dover Publications. Public Broadcasting Service. (2008,

London, UK: British Broadcasting Housen, A. (2002). Aesthetic thought, July 18). Timeline: War in

Corporation. critical thinking, and transfer. Afghanistan. PBS Now. Retrieved

British Broadcasting Corporation. Arts and Learning Journal, 18(1), from www.pbs.org/now/shows/

(2009, February 17). Timeline: 99-132. 428/afghanistan-timeline.html

Soviet war in Afghanistan. BBC Kakar, M. (1995). Afghanistan: The U.S. Department of Labor. (2010). CPS

News. Retrieved from http:// Soviet invasion and the Afghan Table 11. Employed persons by

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_ response, 1978-1982. Berkeley, CA: detailed occupation, sex, race, and

asia/7883532.stm University of California Press. Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Labor

Cooke, A. (2005a). Common threads: Karp, I., Lavine, S., & Rockefeller Force Statistics from the Current

The creation of war textiles around Foundation. (1991). Exhibiting Population Survey, 2010. Bureau of

the world. In A. Cooke and M. cultures: The poetics and politics of Labor Statistics. Washington, DC.

MacDowell (Eds.), Weavings of museum display. Washington, DC: Retrieved from www.bls.gov/cps/

war: Fabrics of memory (pp. 3-29). Smithsonian Institution Press. cpsaat11.pdf

East Lansing, MI: Michigan State Kuryluk, E. (1989). The Afghan war Wolcott, H. (2008). Ethnography:

University Museum Press. rugs. Arts Magazine: New York, A way of seeing. Lanham, MD:

Cooke, A. (2005b). Michgan and 63(6), 72-74. AltaMira Press.

Merza Hozain, Hazara weavers. Lessing, D. (1987). The wind blows

In A. Cooke and M. MacDowell away our words: A firsthand

(Eds.), Weavings of war: Fabrics of account of the Afghan resistance.

memory (pp. 59-62). East Lansing, New York, NY: Random House.

MI: Michigan State University

Lewis, S. (1999). The rhetoric of power

Museum Press.

in the Bayeux Tapestry. New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press.

Endnotes

1 For additional information visit www.vtshome. 3 See the Center for Contemporary Arts

org/ Afghanistan at: www.ccaa.org.af/?p=39

2 See DeWitt Mallary Antique Rug and Textile 4 The interview is available through the online

Art at www.antiqueweavings.com/Detail%20 video source Art Babble at www.artbabble.org/

Pages/Baluch%20Salar%20Khani%20Bagface. video/ima/lida-abdul-factory

html. See also the Textile Museum of Canada 5 See www.barbarakoenen.com.

at www.textilemuseum.ca/apps/index.

cfm?page=collection.browseExh&exhId=271

32 Art Education / November 2011

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Dissonant Worlds: Roger Vandersteene among the CreeDa EverandDissonant Worlds: Roger Vandersteene among the CreeValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Carol Bier Curator Falcons and Flowers SDocumento6 pagineCarol Bier Curator Falcons and Flowers SJacopo Shekari AlamdariNessuna valutazione finora

- Paintings of Bundelkhand: Some Remembered, Some Forgotten, Some not yet DiscoveredDa EverandPaintings of Bundelkhand: Some Remembered, Some Forgotten, Some not yet DiscoveredNessuna valutazione finora

- Safavid PalacesDocumento12 pagineSafavid PalacesmellacrousnofNessuna valutazione finora

- Cavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]Da EverandCavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]Nessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - Kütahya Patterns Out of The BlueDocumento8 pagine08 - Kütahya Patterns Out of The BlueFatih YucelNessuna valutazione finora

- About The Bustan of SaadiDocumento11 pagineAbout The Bustan of SaadiManuel SánchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Gifts of The SultanDocumento6 pagineGifts of The SultanYumna YuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Vol - V Silk Road - Arts of The Book, Painting and Calligraphy BISDocumento69 pagineVol - V Silk Road - Arts of The Book, Painting and Calligraphy BISElizabeth ArosteguiNessuna valutazione finora

- KPK CultureDocumento34 pagineKPK CultureKashif KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Princeton University Press A History of Jewish-Muslim RelationsDocumento10 paginePrinceton University Press A History of Jewish-Muslim Relationshappycrazy99Nessuna valutazione finora

- Abolala Soudavar Reassessing Early SafavDocumento98 pagineAbolala Soudavar Reassessing Early SafavGligor Bozinoski100% (1)

- Hanne - THE MINIATURE ART IN THE MANUSCRIPTS OF THE OTTOMANDocumento13 pagineHanne - THE MINIATURE ART IN THE MANUSCRIPTS OF THE OTTOMANEmre DoğanNessuna valutazione finora

- Grube, Ernest J. - Threasure Od Turkey-The Ottoman Empire (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V. 26, No. 5, January, 1968) .Documento21 pagineGrube, Ernest J. - Threasure Od Turkey-The Ottoman Empire (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V. 26, No. 5, January, 1968) .BubišarbiNessuna valutazione finora

- Qusayr Amra Site Management Plan JanuaryDocumento142 pagineQusayr Amra Site Management Plan JanuaryMoeen HassounaNessuna valutazione finora

- Picturing The Archetypal King Iskandar I PDFDocumento8 paginePicturing The Archetypal King Iskandar I PDFaustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian ArtDocumento18 pagineIndian Artakanksharaj9Nessuna valutazione finora

- 78 in Ns Burn R F M Khu N Ir 11 1 Bronz H I HT M TH M T P Lit N Mu Um RT N Wy RK R R Und 1 1Documento1 pagina78 in Ns Burn R F M Khu N Ir 11 1 Bronz H I HT M TH M T P Lit N Mu Um RT N Wy RK R R Und 1 1parlateNessuna valutazione finora

- The Flowering of Seljuq ArtDocumento19 pagineThe Flowering of Seljuq ArtnusretNessuna valutazione finora

- Akm IstanbulDocumento393 pagineAkm IstanbulMaksut Maksuti100% (1)

- Hermitage Reports 66Documento79 pagineHermitage Reports 66jmagil6092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jahili PoetryDocumento342 pagineJahili PoetryFarhanNessuna valutazione finora

- On Persian CarpetDocumento5 pagineOn Persian CarpetMehrdad SoltanzadehNessuna valutazione finora

- Persian Artists in Mughal IndiaDocumento17 paginePersian Artists in Mughal IndiaAlice Samson100% (1)

- Transformation of Istanbul Craft Guilds (1650-1860Documento19 pagineTransformation of Istanbul Craft Guilds (1650-1860Emre SatıcıNessuna valutazione finora

- سیری در نگارگری ایران PDFDocumento7 pagineسیری در نگارگری ایران PDFPhillip JeffriesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Catalogue of The Turkish Manuscripts in The John Rylands University Library at ManchesterDocumento378 pagineA Catalogue of The Turkish Manuscripts in The John Rylands University Library at ManchesterbolbulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abbasid Lusterware and The Aesthetics o PDFDocumento28 pagineAbbasid Lusterware and The Aesthetics o PDFMarco Antonio Calil MachadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Brit - Museum - Rieu, 1879 - Vol.2 PDFDocumento464 pagineCatalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Brit - Museum - Rieu, 1879 - Vol.2 PDFsi13nz100% (1)

- Ibn Al Fāri, The Poem of The Way, Tr. ArberryDocumento87 pagineIbn Al Fāri, The Poem of The Way, Tr. ArberryZoéNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatolia Cultural FoundationDocumento110 pagineAnatolia Cultural FoundationStewart Bell100% (3)

- Sax, M. y Meeks, N. Manufacture Crystal Mexico. 2009Documento10 pagineSax, M. y Meeks, N. Manufacture Crystal Mexico. 2009Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Tamta ProjectDocumento98 pagineTamta ProjectPranathi ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Solitudes in Silk: A Patan TaleDocumento91 pagineSolitudes in Silk: A Patan TaleAayush VyasNessuna valutazione finora

- Auspicious Carpets: Tibetan Rugs and TextilesDocumento16 pagineAuspicious Carpets: Tibetan Rugs and TextilesyakmanjakNessuna valutazione finora

- Archaeological Museums of PakistanDocumento16 pagineArchaeological Museums of PakistanAsim LaghariNessuna valutazione finora

- Roman Pottery Identification: Alice LyonsDocumento14 pagineRoman Pottery Identification: Alice Lyonssoy yo o noNessuna valutazione finora

- Alexander's Gates: The Legendary Barrier Against Barbarian InvasionDocumento3 pagineAlexander's Gates: The Legendary Barrier Against Barbarian InvasiongavinolNessuna valutazione finora

- Amir Motashemi 2020 CatalogueDocumento108 pagineAmir Motashemi 2020 CatalogueCecilia IidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Seljuk ArchitectureDocumento20 pagineSeljuk ArchitectureuzknNessuna valutazione finora

- Manuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsDocumento18 pagineManuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsfauzanrasipNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic TextilesDocumento3 pagineIslamic TextilesAlisha MasonNessuna valutazione finora

- Srjournal v12Documento213 pagineSrjournal v12TARIQ NAZARWALLNessuna valutazione finora

- Turkish_folk_songs_in_Greek_musical_collDocumento36 pagineTurkish_folk_songs_in_Greek_musical_colltungolcildNessuna valutazione finora

- Seljuk Architecture and Urbanism in AnatoliaDocumento6 pagineSeljuk Architecture and Urbanism in AnatoliaHatem HadiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sultans of Deccan India 1500 1700Documento386 pagineSultans of Deccan India 1500 1700何好甜100% (1)

- Islamic Art: Navigation SearchDocumento26 pagineIslamic Art: Navigation Searchritika_dodejaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chehel Sotoun and Monar Jonban: Isfahan's Iconic PalacesDocumento48 pagineChehel Sotoun and Monar Jonban: Isfahan's Iconic Palacesanam asgharNessuna valutazione finora

- Kufi Design PricingDocumento10 pagineKufi Design PricingPatrick OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Belongs to Hoysala Period Temple Built During 1116ADDocumento6 pagineBelongs to Hoysala Period Temple Built During 1116ADChandni MulakalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ettinghausen, Richard. - Islamic Art.Documento53 pagineEttinghausen, Richard. - Islamic Art.BubišarbiNessuna valutazione finora

- On Ship Construction in AntiquityDocumento635 pagineOn Ship Construction in AntiquitySérgio ContreirasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Production of Silk AndalusiaDocumento10 pagineThe Production of Silk Andalusianitakuri100% (1)

- Tabriz International Entrepot Under TheDocumento39 pagineTabriz International Entrepot Under Theaytaç kayaNessuna valutazione finora

- (H) Persian Literature (Afro-Asian Lit)Documento14 pagine(H) Persian Literature (Afro-Asian Lit)Joyce RueloNessuna valutazione finora

- PowerPoint (Mughal Art)Documento10 paginePowerPoint (Mughal Art)Mohit KhicharNessuna valutazione finora

- 2004 Adamova Iconography of A Camel FightDocumento14 pagine2004 Adamova Iconography of A Camel FightlamiabaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Metropolitan Museum Journal V 22 1987 PDFDocumento186 pagineThe Metropolitan Museum Journal V 22 1987 PDFantony100% (2)

- History of Ottoman CalligraphyDocumento7 pagineHistory of Ottoman Calligraphykalligrapher100% (1)

- The history and global influence of the Indian mango motif known as "Ambi" or "PaisleyDocumento19 pagineThe history and global influence of the Indian mango motif known as "Ambi" or "PaisleyLia AmmuNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsDocumento10 pagineChapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsALANKRIT TRIPATHINessuna valutazione finora

- Stress-Busting Plan for Life's ChallengesDocumento3 pagineStress-Busting Plan for Life's Challengesliera sicadNessuna valutazione finora

- EAPP Module 5Documento10 pagineEAPP Module 5Ma. Khulyn AlvarezNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis PromptsDocumento7 pagineThesis Promptsauroratuckernewyork100% (2)

- Eco 301 Final Exam ReviewDocumento14 pagineEco 301 Final Exam ReviewCảnh DươngNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study On Global Branding - DuluxDocumento18 pagineCase Study On Global Branding - DuluxAakriti NegiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ultra Slimpak G448-0002: Bridge Input Field Configurable IsolatorDocumento4 pagineUltra Slimpak G448-0002: Bridge Input Field Configurable IsolatorVladimirNessuna valutazione finora

- Assurance Audit of Prepaid ExpendituresDocumento7 pagineAssurance Audit of Prepaid ExpendituresRatna Dwi YulintinaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Teacher and The LearnerDocumento23 pagineThe Teacher and The LearnerUnique Alegarbes Labra-SajolNessuna valutazione finora

- Working Capital Management at Padmavathi Co-operative BankDocumento53 pagineWorking Capital Management at Padmavathi Co-operative BankMamidishetty Manasa67% (3)

- Cytogenectics Reading ListDocumento2 pagineCytogenectics Reading ListHassan GillNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality of Good TeacherDocumento5 pagineQuality of Good TeacherRandyNessuna valutazione finora

- Douglas Frayne Sargonic and Gutian Periods, 2334-2113 BCDocumento182 pagineDouglas Frayne Sargonic and Gutian Periods, 2334-2113 BClibrary364100% (3)

- MechanismDocumento17 pagineMechanismm_er100Nessuna valutazione finora

- Database Case Study Mountain View HospitalDocumento6 pagineDatabase Case Study Mountain View HospitalNicole Tulagan57% (7)

- Land Equivalent Ratio, Growth, Yield and Yield Components Response of Mono-Cropped vs. Inter-Cropped Common Bean and Maize With and Without Compost ApplicationDocumento10 pagineLand Equivalent Ratio, Growth, Yield and Yield Components Response of Mono-Cropped vs. Inter-Cropped Common Bean and Maize With and Without Compost ApplicationsardinetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Modul English For Study SkillsDocumento9 pagineModul English For Study SkillsRazan Nuhad Dzulfaqor razannuhad.2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Historical Cultural Memory in Uzbek Documentary CinemaDocumento5 pagineThe Role of Historical Cultural Memory in Uzbek Documentary CinemaResearch ParkNessuna valutazione finora

- Repair Max II Pump 310894lDocumento20 pagineRepair Max II Pump 310894lAndreina FajardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Case Study 0506Documento25 pagineFinal Case Study 0506Namit Nahar67% (3)

- Transactionreceipt Ethereum: Transaction IdentifierDocumento1 paginaTransactionreceipt Ethereum: Transaction IdentifierVALR INVESTMENTNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.9 Bernoulli's Equation: GZ V P GZ V PDocumento1 pagina1.9 Bernoulli's Equation: GZ V P GZ V PTruong NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentDocumento44 pagineUnderstanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentS.Rengasamy89% (28)

- Strategicmanagement Finalpaper 2ndtrisem 1819Documento25 pagineStrategicmanagement Finalpaper 2ndtrisem 1819Alyanna Parafina Uy100% (1)

- E TN SWD Csa A23 3 94 001 PDFDocumento9 pagineE TN SWD Csa A23 3 94 001 PDFRazvan RobertNessuna valutazione finora

- Nurses Week Program InvitationDocumento2 pagineNurses Week Program InvitationBenilda TuanoNessuna valutazione finora

- PremiumpaymentReceipt 10663358Documento1 paginaPremiumpaymentReceipt 10663358Kartheek ChandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Silyzer 300 - Next Generation PEM ElectrolysisDocumento2 pagineSilyzer 300 - Next Generation PEM ElectrolysisSaul Villalba100% (1)

- Food 8 - Part 2Documento7 pagineFood 8 - Part 2Mónica MaiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Atlanta Pipes and FittingsDocumento2 pagineAtlanta Pipes and Fittingsotadoyreychie31Nessuna valutazione finora

- Economics for Kids - Understanding the Basics of An Economy | Economics 101 for Children | 3rd Grade Social StudiesDa EverandEconomics for Kids - Understanding the Basics of An Economy | Economics 101 for Children | 3rd Grade Social StudiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Prison Pedagogies: Learning and Teaching with Imprisoned WritersDa EverandPrison Pedagogies: Learning and Teaching with Imprisoned WritersNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Anxiety and Shyness: The definitive guide to learn How to Become Self-Confident with Self-Esteem and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Stop Being Dominated by ShynessDa EverandSocial Anxiety and Shyness: The definitive guide to learn How to Become Self-Confident with Self-Esteem and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Stop Being Dominated by ShynessValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (11)

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyDa EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- World Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesDa EverandWorld Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- U.S. History Puzzles, Book 3, Grades 5 - 8Da EverandU.S. History Puzzles, Book 3, Grades 5 - 8Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Child Psychology and Development For DummiesDa EverandChild Psychology and Development For DummiesValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- U.S. History Skillbook: Practice and Application of Historical Thinking Skills for AP U.S. HistoryDa EverandU.S. History Skillbook: Practice and Application of Historical Thinking Skills for AP U.S. HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- 101 Social Studies Activities for Curious KidsDa Everand101 Social Studies Activities for Curious KidsNessuna valutazione finora

- World Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12Da EverandWorld Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Student's Guide to Political PhilosophyDa EverandA Student's Guide to Political PhilosophyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (18)

- Our Global Village - Ireland: A Cultural Resource GuideDa EverandOur Global Village - Ireland: A Cultural Resource GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All UpDa EverandListening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All UpNessuna valutazione finora

![Cavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259895835/149x198/d6694d2e61/1617227775?v=1)