Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Science Food Security PDF

Caricato da

Ali HaiderDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Science Food Security PDF

Caricato da

Ali HaiderCopyright:

Formati disponibili

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS?

SPECIAL SECTION

VIEWPOINT

Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies

Mark W. Rosegrant* and Sarah A. Cline

Global food security will remain a worldwide concern for the next 50 years and nearly 35-year delay in meeting the Millennium

beyond. Recently, crop yield has fallen in many areas because of declining invest- Development Goals. In some places, circum-

ments in research and infrastructure, as well as increasing water scarcity. Climate stances will deteriorate, and in sub-Saharan

change and HIV/AIDS are also crucial factors affecting food security in many regions. Africa, the number of malnourished preschool

Although agroecological approaches offer some promise for improving yields, food children will increase between 1997 and 2015,

security in developing countries could be substantially improved by increased in- after which they will only decrease slightly

vestment and policy reforms. until 2050. South Asia is another region of

concernalthough progress is expected in this

The ability of agriculture to support growing erosion and desertification. Increasing devel- region, more than 30% of preschool children

populations has been a concern for genera- opment into marginal lands may in turn put will remain malnourished by 2030, and 24% by

tions and continues to be high on the global these areas at greater risk of environmental 2050 (21).

policy agenda. The eradication of poverty degradation (10, 11). The HIV/AIDS epidem- Achieving food security needs policy

and hunger was included as one of the United ic is another global concern, with an estimat- and investment reforms on multiple fronts,

Nations Millennium Development Goals ed 42 million cases worldwide at the end of including human resources, agricultural re-

adopted in 2000. One of the targets of the 2002 (12); 95% of those are in developing search, rural infrastructure, water resourc-

Goals is to halve the proportion of people countries. In addition to its direct health, es, and farm- and community-based agri-

who suffer from hunger between 1990 and economic, and social impacts, the disease cultural and natural resources management.

2015 (1). Meeting this food security goal will also affects food security and nutrition. Adult Progressive policy action must not only

be a major challenge. Predictions of food labor is often removed from affected house- increase agricultural production, but also

security outcomes have been a part of the holds, and these households will have less boost incomes and reduce poverty in rural

policy landscape since Malthus An Essay on capacity to produce or buy food, as assets are areas where most of the poor live. If we

the Principle of Population of 1798 (2). Over often depleted for medical or funeral costs take such an approach, we can expect pro-

the past several decades, some experts have (13). The agricultural knowledge base will duction between 1997 and 2050 to increase

expressed concern about the ability of agri- deteriorate as individuals with farming and by 71% for cereals and by 131% for meats.

cultural production to keep up with global science experience succumb to the disease A reduction in childhood malnutrition

food demands (35), whereas others have (14). Can food security goals be met in the would follow; the number of malnourished

forecast that technological advances or ex- face of these old and new challenges? children would decline from 33 million in

pansions of cultivated area would boost pro- Several organizations have developed quan- 1997 to 16 million in 2050 in sub-Saharan

duction sufficiently to meet rising demands titative models that project global food supply Africa, and from 85 million to 19 million in

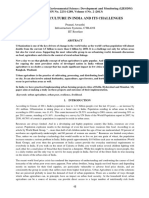

(68). So far, dire predictions of a global food and demand into the future (1519). According South Asia (Fig. 1).

security catastrophe have been unfounded. to the most recent baseline projections of the Increased investment in people is essential

Nevertheless, crop yield growth has International Food Policy Research Institutes to accelerate food security improvements. In

slowed in much of the world because of (IFPRIs) International Model for Policy Anal- agricultural areas, education works directly to

declining investments in agricultural re- ysis of Agricultural Commodities and Trade enhance the ability of farmers to adopt more

search, irrigation, and rural infrastructure and (IMPACT) (20), global cereal

increasing water scarcity. New challenges to production is estimated to in-

food security are posed by climate change crease by 56% between 1997 and

and the morbidity and mortality of human 2050, and livestock production

immunodeficiency virus/acquired immuno- by 90%. Developing countries

deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Many will account for 93% of cereal-

studies predict that world food supply will demand growth and 85% of

not be adversely affected by moderate cli- meat-demand growth to 2050.

mate change, by assuming farmers will take Income growth and rapid urban-

adequate steps to adjust to climate change ization are major forces driving

and that additional CO2 will increase yields increased demand for higher val-

(9). However, many developing countries are ued commodities, such as meats,

likely to fare badly. In warmer or tropical fruits, and vegetables. Interna-

environments, climate change may result in tional agricultural trade will in-

more intense rainfall events between pro- crease substantially, with devel-

longed dry periods, as well as reduced or oping countries cereal imports

more variable water resources for irrigation. doubling by 2025 and tripling by

Such conditions may promote pests and dis- 2050. Child malnutrition will Fig. 1. Projected number of malnourished children in South

ease on crops and livestock, as well as soil persist in many developing coun- Asia and sub-Saharan Africa under baseline and progressive

tries, although overall, the share policy actions scenarios, 1997 to 2050. Blue-green squares,

South Asia, baseline scenario; red asterisks, South Asia, pro-

International Food Policy Research Institute, 2033 K of malnourished children is pro- gressive policy actions scenario; yellow diamonds, sub-Saharan

Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20006, USA. jected to decline from 31% in Africa, baseline scenario; purple triangles, sub-Saharan Africa,

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E- 1997 to 14% in 2050 (Fig. 1). progressive policy actions scenario. Source: International Food

mail: m.rosegrant@cgiar.org Nevertheless, this represents a Policy Research Institute (21).

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 302 12 DECEMBER 2003 1917

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS?

SPECIAL SECTION

advanced technologies and crop-management cation of molecular biotechnology has been tem services. All of these issues require invest-

techniques and to achieve higher rates of mostly limited to a small number of traits of ment in research, system development, and

return on land (22). Moreover, education en- interest to commercial farmers, mainly devel- knowledge sharing.

courages movement into more remunerative oped by a few global life science companies. To implement agricultural innovation, we

nonfarm work, thus increasing household in- Although much of the science and many need collective action at the local level, as

come. Womens education affects nearly ev- of the tools and intermediate products of well as the participation of government and

ery dimension of development, from lower- biotechnology are transferable to solve high- nongovernmental organizations that work at

ing fertility rates to raising productivity and priority problems in the tropics and subtrop- the community level. There have been sever-

improving environmental management (23). ics, it is generally agreed that the private al successful programs, including those that

Research in Brazil shows that 25% of chil- sector will not invest sufficiently to make the use water harvesting and conservation tech-

dren were stunted if their mothers had four or needed adaptations in these regions with lim- niques (42, 43). Another priority is participa-

fewer years of schooling; however, this fig- ited market potential. Consequently, the pub- tory plant breeding for yield increases in

ure fell to 15% if the mothers had a primary lic sector will have to play a key role, much rainfed agrosystems, particularly in dry and

education and to 3% if mothers had any of it by accessing proprietary tools and prod- remote areas. Farmer participation can be

secondary education (24). Poverty reduction ucts from the private sector (37). used in the very early stages of breed selec-

is usually enhanced by an increase in the Irrigation is the largest water user world- tion to help find crops suited to a multitude of

proportion of educational resources going to wide, but also the first sector to lose out as environments and farmer preferences. It may

primary education and to the poorest groups scarcity increases (38). The challenges of be the only feasible route for crop breeding in

or regions (2527). Investments in health and water scarcity are heightened by the increas- remote regions, where a high level of crop

nutrition, including safe drinking water, im- ing costs of developing new water sources, diversity is required within the same farm, or

proved sewage disposal, immunization, and soil degradation in irrigated areas, groundwa- for minor crops that are neglected by formal

public health services, also contribute to pov- ter depletion, water pollution, and ecosystem breeding programs (44, 45).

erty reduction. For example, a study in Ethio- degradation. Wasteful use of already devel- Making substantial progress in improving

pia shows that the distance to a water source, as oped water supplies may be encouraged by food security will be difficult, and it does mean

well as nutrition and morbidity, all affect agri- subsidies and distorted incentives that influ- reform of currently accepted agricultural practices.

cultural productivity of households (28). ence water use. Hence, investment is needed However, innovations in agroecological ap-

When rural infrastructure has deteriorated to develop new water management policies proaches and crop breeding have brought some

or is nonexistent, the cost of marketing farm and infrastructure. Although the economic documented successes. Together with investment

produce, and thus escaping subsistence agri- and environmental costs of irrigation make in research and water and transport infrastructure,

culture and improving incomes, can be pro- many investments unprofitable, much could we can make major improvements to global food

hibitive for poor farmers. Rural roads in- be achieved by water conservation and in- security, especially for the rural poor.

crease agricultural production by bringing creased efficiency in existing systems and by

new land into cultivation and by intensifying increased crop productivity per unit of water References

existing land use, as well as consolidating the used. Regardless, more research and policy 1. The World Bank Group, Millennium Development

Goals: About the Goals, www.developmentgoals.

links between agricultural and nonagricultur- efforts need to be focused on rainfed agricul- org/About_the_goals.htm (2003).

al activities within rural areas and between ture. Exploiting the full potential of rainfed 2. T. R. Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population

rural and urban areas (29). Government ex- agriculture will require investment in water (Norton, New York, 2003).

3. P. R. Ehrlich, A. H. Ehrlich, The Population Explosion

penditure on roads is the most important fac- harvesting technologies, crop breeding, and (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1990).

tor in poverty alleviation in rural areas of extension services, as well as good access to 4. L. Brown, H. Kane, Full House: Reassessing the Earths

India and China, because it leads to new markets, credit, and supplies. Water harvest- Population Carrying Capacity (Norton, New York, 1994).

5. D. H. Meadows, D. L. Meadows, J. Randers, Beyond the

employment opportunities, higher wages, and ing and conservation techniques are particu- Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a

increased productivity (30, 31). larly promising for the semi-arid tropics of Sustainable Future (Chelsea Green, White River Junc-

In addition to being a primary source of Asia and Africa, where agricultural growth tion, VT, 1992).

6. E. Boserup, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth:

crop and livestock improvement, invest- has been less than 1% in recent years. For The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population

ment in agricultural research has high eco- example, water harvesting trials in Burkina Pressure (Aldine, Chicago, 1965).

nomic rates of return (32). Three major Faso, Kenya, Niger, Sudan, and Tanzania show 7. C. Clark, Starvation or Plenty (Taplinger, New York, 1970).

yield-enhancing strategies include research increases in yield of a factor of 2 to 3, compared 8. J. L. Simon, The Ultimate Resource 2 (Princeton Univ.

Press, Princeton, NJ, 1998).

to increase the harvest index (33), plant with dryland farming systems (39, 40). 9. R. M. Adams, B. H. Hurd, Choices 14, 22 (1999).

biomass, and stress tolerance (particularly Agroecological approaches that seek to 10. T. E. Downing, Renewable Energy 3, 491 (1993).

drought resistance) (34, 35). For example, manage landscapes for both agricultural pro- 11. International Panel on Climate Change, Climate

Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability

the hybrid New Rice for Africa, which duction and ecosystem services are another way (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2001).

was bred to grow in the uplands of West of improving agricultural productivity. A study 12. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS),

Africa, produces more than 50% more grain of 45 projects, using agroecological approach- www.unaids.org (2003).

13. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United

than current varieties when cultivated in es, in 17 African countries shows cereal yield Nations (FAO), The impact of HIV/AIDS on food

traditional rainfed systems without fertiliz- improvements of 50 to 100 percent (41). There security, Committee on World Food Security, 27th

er. Moreover, this variety matures 30 to 50 are many concomitant benefits to such ap- Session, Rome, 28 May to 1 June, 2001.

14. L. Haddad, S. Gillespie, J. Int. Dev. 13, 487 (2001).

days earlier than current varieties and has proaches, as they reduce pollution through al- 15. J. Bruinsma, Ed., World Agriculture: Towards 2015/

enhanced disease and drought tolerance ternative methods of nutrient and pest manage- 2030: An FAO Study (Earthscan, London, 2003).

(36). In addition to conventional breeding, ment, create biodiversity reserves, and enhance 16. Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute, U.S. and

World Agricultural Outlook 2003 (Staff Report 1-03, Food

recent developments in nonconventional habitat quality through careful management of and Agricultural Policy Research Institute, University of

breeding, such as marker-assisted selection soil, water, and natural vegetation. Important Iowa and University of MissouriColumbia, 2003).

and cell and tissue culture techniques, could issues remain about how to scale up agroeco- 17. M. W. Rosegrant, M. Paisner, S. Meijer, J. Whitcover,

be employed for crops in developing coun- logical approaches. Pilot programs are needed Global Food Projections to 2020: Emerging Trends and

Alternative Futures (IFPRI, Washington, DC, 2001).

tries, even if these countries stop short of to work out how to mobilize private investment 18. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel-

transgenic breeding. To date, however, appli- and to develop systems for payment of ecosys- opment, Agricultural Outlook 20032008 (Organisa-

1918 12 DECEMBER 2003 VOL 302 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS?

SPECIAL SECTION

tion for Economic Co-operation and Development, 29. International Fund for Agricultural Development Knowledge and Information Systems Discussion Pa-

Paris, 2003). (IFAD), The State of World Rural Poverty: A Prole of per, The World Bank, Washington, DC, 2000).

19. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ofce of the Chief Asia (IFAD, Rome, 1995). 38. M. W. Rosegrant, X. Cai, S. A. Cline, World Water and

Economist, USDA Agricultural Baseline Projections 30. S. Fan, P. Hazell, S. Thorat, Am. J. Agric. Econ. 82, Food to 2025: Dealing with Scarcity (IFPRI, Washing-

to 2012 (Staff Report WAOB-2003-1, U.S. Depart- 1038 (2000). ton, DC, 2002).

ment of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 2003). 31. S. Fan, L. Zhang, X. Zhang, Growth, inequality, and 39. S. M. Barghouti, Sustain. Dev. Int. 1, 127 (2001),

20. M. W. Rosegrant, S. Meijer, S. A. Cline, Interna- poverty in rural China: The role of public invest- www.sustdev.org/agriculture/articles/edition1/01.

tional Model for Policy Analysis of Agricultural ments (IFPRI Research Report 125, IFPRI, Washing- 127.pdf.

Commodities and Trade (IMPACT ): Model descrip- ton, DC, 2002). 40. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

tion (IFPRI, Washington, DC, 2002), available at 32. J. M. Alston, P. G. Pardey, C. Chan-Kang, T. J. Wyatt, Nations, Crops and Drops (FAO, Rome, 2000).

www.ifpri.org/themes/impact/impactmodel.pdf. M. C. Marra, A meta-analysis of rates of return to 41. J. Pretty, Environ. Dev. Sustain. 1, 253 (1999).

21. International Food Policy Research Institute, unpub- agricultural R&D: Ex pede Herculem? (IFPRI 42. J. Pretty, World Dev. 23, 1247 (1995).

lished data. Research Report 113, IFPRI, Washington, DC, 43. T. Oweis, A. Hachum, J. Kijne, Water harvesting and

22. World Bank, Poverty: World Development Indicators 2000). supplementary irrigation for improved water use ef-

(Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1990). 33. The harvest index is dened as the ratio of grain to ciency in dry areas (System-Wide Initiative on

23. World Bank, Poverty Reduction and the World Bank: Water Management Paper 7, International Water

total crop biomass (34).

Progress and Challenges in the 1990s (The Inter- Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1999).

34. K. G. Cassman, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5952

national Bank for Reconstruction and Develop- 44. S. Ceccarelli, S. Grando, R. H. Booth, in Participatory

(1999).

ment/The World Bank, Washington, DC, 1996). Plant Breeding, P. Eyzaguire, M. Iwanaga, Eds. (Inter-

24. A. Kassouf, B. Senauer, Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 44, 35. L. T. Evans, Feeding the Ten Billion: Plants and Popula-

tion Growth (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1998). national Plant Genetics Research Institute, Rome,

817 (1996). 1996), pp. 99 116.

25. M. Lipton, S. Yaqub, E. Darbellay, Success in Anti- 36. West Africa Rice Development Association, Con-

sortium formed to rapidly disseminate New Rice 45. J. Kornegay, J. A. Beltran, J. Ashby, in Participatory

Poverty (International Labour Ofce, Geneva, 1998). Plant Breeding, P. Eyzaguire, M. Iwanaga, Eds. (Inter-

26. R. Gaiha, Design of Poverty Alleviation Strategy in for Africa, available at www.warda.org/warda1/

main/newsrelease/newsrel-consortiumapr01.htm national Plant Genetics Research Institute, Rome,

Rural Areas (FAO, Rome, 1994).

[cited 2000]. 1996), pp. 151159.

27. R. Singh, P. Hazell, Econ. Polit. Wkly. 28, A9 (20

March 1993). 37. D. Byerlee, K. Fischer, Accessing modern science: Web Resources

28. A. Croppenstedt, C. Muller, Econ. Dev. Cult. Change Policy and institutional options for agricultural bio- www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/302/5652/1917/

48, 475 (2000). technology in developing countries (Agricultural DC1

VIEWPOINT

New Visions for Addressing Sustainability

A. J. McMichael,1* C. D. Butler,1 Carl Folke2

Attaining sustainability will require concerted interactive efforts among disciplines, many of disciplinary collaboration of other social and nat-

which have not yet recognized, and internalized, the relevance of environmental issues to ural sciences, engineering, and the humanities (3).

their main intellectual discourse. The inability of key scientic disciplines to engage interac- Neither mainstream demography nor eco-

tively is an obstacle to the actual attainment of sustainability. For example, in the list of nomics, for the most part, incorporates suffi-

Millennium Development Goals from the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable cient appreciation of environmental criticalities

Development, Johannesburg, 2002, the seventh of the eight goals, to ensure environmental into their thinking. They implictly assume that

sustainability, is presented separately from the parallel goals of reducing fertility and the world is an open, steady-state system within

poverty, improving gains in equity, improving material conditions, and enhancing population which discipline-specific processes can be stud-

health. A more integrated and consilient approach to sustainability is urgently needed. ied. Although contemporary ecology has

broadened its perspectives significantly, there

For human populations, sustainability means mance, greater energy efficiency, better urban is a tendency to exclude consideration of both

transforming our ways of living to maximize the design, improved transport systems, better con- human influence and dependence on ecosys-

chances that environmental and social conditions servation of recreational amenities, and so on. tem composition, development, and dynam-

will indefinitely support human security, well- However, such changes in technologies, behav- ics. Epidemiologists focus mainly on

being, and health. In particular, the flow of non- iors, amenities, and equity are only the means to individual-level behaviors and circumstances

substitutable goods and services from ecosystems attaining desired human experiential outcomes, as causes of disease. This discounts the un-

must be sustained. The contemporary stimulus for including autonomy, opportunity, security, and derlying social, cultural, and political deter-

exploring sustainability is the accruing evidence health. These are the true ends of sustainabil- minants of the distribution of disease risk

that humankind is jeopardizing its own longer ityand there has been some recognition that within and between populations, and has

term interests by living beyond Earths means, their attainment, and their sharing, will be op- barely recognized the health risks posed by

thereby changing atmospheric composition and timized by reducing the rich-poor divide (2). todays global environmental changes.

depleting biodiversity, soil fertility, ocean fisher- Some reasons for the failure to achieve a col- These four disciplines share a limited ability

ies, and freshwater supplies (1). lective vision of how to attain sustainability lie in to appreciate that the fate of human populations

Much early discussion about sustainability the limitations of, and disjunction between, disci- depends on the biospheres capacity to provide a

has focused on readily measurable intermediate plines we think should be central to our under- continued flow of goods and services. The as-

outcomes such as increased economic perfor- standing of sustainability: demography, econom- sumption of human separateness from the natu-

ics, ecology, and epidemiology. These disciplines ral world perpetuates a long-standing, biblically

bear on the size and economic activities of the based premise of Western scientific thought of

1

National Centre for Epidemiology and Population

Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

human population, how the population relates to Man as master, with dominion over Nature (4).

0200, Australia. 2Department of Systems Ecology, the natural world, and the health consequences of Many disciplines still apply world views that

Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden. ecologically injudicious behavior. Sustainability predate current understanding of complex sys-

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E- issues are of course not limited to these four tem dynamics and of how human evolutionary

mail: tony.mcmichael@anu.edu.au disciplines, but require the engagement and inter- history has developed with, and helped shape,

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 302 12 DECEMBER 2003 1919

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies: Science January 2004Documento4 pagineGlobal Food Security: Challenges and Policies: Science January 2004tualaNessuna valutazione finora

- Food Systems and The Triple ChallengeDocumento4 pagineFood Systems and The Triple Challengeasbath alassaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S2211912422000438 MainDocumento10 pagine1 s2.0 S2211912422000438 Maincaroloops.liaoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of Food and AgricultureDocumento4 pagineThe Future of Food and AgriculturemarcoNessuna valutazione finora

- 4ADocumento9 pagine4Adyz2nybk8zNessuna valutazione finora

- Crop Production Session 1Documento9 pagineCrop Production Session 1wwaweru210Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2Documento7 pagineChapter 2Ephesiany BantawanNessuna valutazione finora

- The SDGDocumento5 pagineThe SDGFerly Ann BaculinaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 SPRFP New Paradigma Plant NutritienDocumento7 pagine2020 SPRFP New Paradigma Plant NutritienusmanalihaashmiNessuna valutazione finora

- AERC Special Call For Proposals Group E August 2023Documento10 pagineAERC Special Call For Proposals Group E August 2023Percival KufamusariraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Increasing Hunger Concern and Current Need in The Development of Sustainable Food Security in The Developing CountriesDocumento7 pagineThe Increasing Hunger Concern and Current Need in The Development of Sustainable Food Security in The Developing CountriesFaith Ann Miguel TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Climate-Smart Agriculture and Smallholder Farmers: The Critical Role of Technology Justice in Effective AdaptationDocumento16 pagineClimate-Smart Agriculture and Smallholder Farmers: The Critical Role of Technology Justice in Effective AdaptationShila SafeNessuna valutazione finora

- UNDP Gender, CC and Food Security Policy Brief 3-WEBDocumento8 pagineUNDP Gender, CC and Food Security Policy Brief 3-WEBCristian GuettioNessuna valutazione finora

- Climate-Smart Agriculture For Food Security (2014)Documento6 pagineClimate-Smart Agriculture For Food Security (2014)Lance ScottNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethiopia Policy Review - Info Note - Final June 2020Documento5 pagineEthiopia Policy Review - Info Note - Final June 2020Esmi MusaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of Food and Agriculture Trends and ChallengesDocumento11 pagineThe Future of Food and Agriculture Trends and ChallengeskaeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of Agriculture: Challenges For Environment, Health and Safety Regulation of PesticidesDocumento4 pagineThe Future of Agriculture: Challenges For Environment, Health and Safety Regulation of PesticidesMamato MarcelloNessuna valutazione finora

- Ensuring Food Security During THE Pandemic: Review of Short-Term Responses in Selected CountriesDocumento9 pagineEnsuring Food Security During THE Pandemic: Review of Short-Term Responses in Selected CountriesMarie Cris Gajete MadridNessuna valutazione finora

- PB - 20-26 (F MEngoub) PDFDocumento9 paginePB - 20-26 (F MEngoub) PDFMarie Cris Gajete MadridNessuna valutazione finora

- Losses in The Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions: SustainabilityDocumento18 pagineLosses in The Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions: Sustainabilitymusic freakNessuna valutazione finora

- Land & Food Security Recounted Land Portal 2Documento1 paginaLand & Food Security Recounted Land Portal 2KristianNessuna valutazione finora

- Comm RRLDocumento4 pagineComm RRLayen esperoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Technology in AgricultureDocumento35 pagineThe Role of Technology in AgricultureDivyesh ThumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Agro-Technological Systems in Traditional Agriculture Assistance A Systematic ReviewDocumento23 pagineAgro-Technological Systems in Traditional Agriculture Assistance A Systematic ReviewDivya MNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of COVID-19 On Food Security and Nutrition UN Policy Brief June 2020Documento23 pagineThe Impact of COVID-19 On Food Security and Nutrition UN Policy Brief June 2020wow proNessuna valutazione finora

- Pingali GreenRevolution PNASJuly312012 PDFDocumento8 paginePingali GreenRevolution PNASJuly312012 PDFanon_20637111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Science & Technology in Achieving It: UNSDG Goal 2: Zero HungerDocumento2 pagineRole of Science & Technology in Achieving It: UNSDG Goal 2: Zero HungerDharmendra SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Land & Food Security Recounted Land PortalDocumento1 paginaLand & Food Security Recounted Land PortalKristianNessuna valutazione finora

- TCW Module 14 The Global Food SecurityDocumento5 pagineTCW Module 14 The Global Food SecuritySamantha SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Computer PresentationDocumento9 pagineComputer PresentationDebmalyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Food Security - FinalDocumento34 pagineGlobal Food Security - FinalCatherine FetizananNessuna valutazione finora

- 100 Facts in 14 Themes Linking People, Food and The PlanetDocumento14 pagine100 Facts in 14 Themes Linking People, Food and The PlanetAjinkya JadhaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S2666154321000922 MainDocumento10 pagine1 s2.0 S2666154321000922 MainFaith Ann Miguel TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Outlooks On Pest MGMT ArticleDocumento4 pagineOutlooks On Pest MGMT ArticleNorberto R. BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- CWorld 3 - Midterm (SDG Goals)Documento4 pagineCWorld 3 - Midterm (SDG Goals)NEIL NETTE S. REYNALDONessuna valutazione finora

- Regional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificDa EverandRegional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificNessuna valutazione finora

- Ielts Foundation - Study - Skills (Dragged)Documento7 pagineIelts Foundation - Study - Skills (Dragged)Việt Anh VũNessuna valutazione finora

- Long-Term Challenges To Food Security and Rural Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocumento8 pagineLong-Term Challenges To Food Security and Rural Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan AfricaAgripolicyoutreachNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Food SecurityDocumento3 pagineGlobal Food SecurityKenneth50% (2)

- 2Documento6 pagine2dyz2nybk8zNessuna valutazione finora

- PGIM Megatrends - Food For Thought - Investment Opportunities Across A Changing Food SystemDocumento44 paginePGIM Megatrends - Food For Thought - Investment Opportunities Across A Changing Food SystempssaenzNessuna valutazione finora

- Green Revolution: Impacts, Limits, and The Path AheadDocumento7 pagineGreen Revolution: Impacts, Limits, and The Path Aheadbrianna innocentNessuna valutazione finora

- Food SystemsDocumento6 pagineFood SystemsMaria Laura LheritierNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy BriefDocumento3 paginePolicy BriefIik PandaranggaNessuna valutazione finora

- Geographical Information System (GIS) : A Panacea For Food Insecurity in Nigeria (A Review)Documento8 pagineGeographical Information System (GIS) : A Panacea For Food Insecurity in Nigeria (A Review)Paper PublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics, PoliticsDocumento11 pagineEconomics, Politicsbea gutierrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Position PaperDocumento8 paginePosition Papermjdr040804Nessuna valutazione finora

- 31 Session of The Committee On World Food Security 23-26 May 2005Documento10 pagine31 Session of The Committee On World Food Security 23-26 May 2005willy limNessuna valutazione finora

- Call For ProposalDocumento26 pagineCall For ProposalNega TewoldeNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S2211912422000505 MainDocumento9 pagine1 s2.0 S2211912422000505 MainKaterina BlackNessuna valutazione finora

- GM Crops in AfricaDocumento14 pagineGM Crops in AfricaShazia SaifNessuna valutazione finora

- Kostasstamoulis How To Achive 2030 Feed A Zero HungerDocumento10 pagineKostasstamoulis How To Achive 2030 Feed A Zero HungerTiara Kurnia Khoerunnisa FapertaNessuna valutazione finora

- National Intelligence Council - Intelligence Community Assessment - Global Food Security - 22 September 2015Documento58 pagineNational Intelligence Council - Intelligence Community Assessment - Global Food Security - 22 September 2015Seni NabouNessuna valutazione finora

- The Fulture of Food and AgricultureDocumento52 pagineThe Fulture of Food and AgricultureCayo GomesNessuna valutazione finora

- Rachel Global Food Security in Todays WorldDocumento10 pagineRachel Global Food Security in Todays WorldRose ann OlaerNessuna valutazione finora

- Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018: Addressing the Threat from Climate Variability and Extremes for Food Security and NutritionDa EverandAfrica Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018: Addressing the Threat from Climate Variability and Extremes for Food Security and NutritionNessuna valutazione finora

- Jumlah Konsumsi Jagung GlobalDocumento21 pagineJumlah Konsumsi Jagung GlobalVincentius EdwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Blended Finance For AgricultureDocumento12 pagineBlended Finance For AgricultureEggtaNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Feed The World in 2050Documento35 pagineHow To Feed The World in 2050i-callNessuna valutazione finora

- Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2017. The Food Security and Nutrition–Conflict Nexus: Building Resilience for Food Security, Nutrition and PeaceDa EverandAfrica Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2017. The Food Security and Nutrition–Conflict Nexus: Building Resilience for Food Security, Nutrition and PeaceNessuna valutazione finora

- White Fragility: Why It's So Hard For White People To Talk About RacismDocumento4 pagineWhite Fragility: Why It's So Hard For White People To Talk About RacismAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- 13.englishijel TaufiqrafatspoetrythekaleidoscopeDocumento11 pagine13.englishijel TaufiqrafatspoetrythekaleidoscopeAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Frey2019 PDFDocumento3 pagineFrey2019 PDFAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Punjab Public Service CommissionDocumento1 paginaPunjab Public Service CommissionAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Wasafiri: Colonial or Other' Writing inDocumento4 pagineWasafiri: Colonial or Other' Writing inAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Wingate2012 PDFDocumento10 pagineWingate2012 PDFAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Government of Punjab Department of Social Security, Women & Child Development (Social Security Branch)Documento12 pagineGovernment of Punjab Department of Social Security, Women & Child Development (Social Security Branch)Ali HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Antony PDFDocumento24 pagineAntony PDFAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Sulter Exit WestDocumento2 pagineSulter Exit WestAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Historiography of The Subject in Austen, Keats, and ByronDocumento2 pagineHistoriography of The Subject in Austen, Keats, and ByronAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Ernst Slav It 2017Documento10 pagineErnst Slav It 2017Ali HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Linguistics and Education: Joseph C. RumenappDocumento11 pagineLinguistics and Education: Joseph C. RumenappAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cherry Orchard Study Guide FinalDocumento17 pagineThe Cherry Orchard Study Guide FinalAli Haider100% (1)

- The New Comparative Literature A Review Article of Work by Bassn PDFDocumento5 pagineThe New Comparative Literature A Review Article of Work by Bassn PDFAli HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Keshav Memorial Institute of Technology: B.Tech I Year Course Structure (KR21 Regulations)Documento38 pagineKeshav Memorial Institute of Technology: B.Tech I Year Course Structure (KR21 Regulations)Chigullapally SushmithaNessuna valutazione finora

- Yam Bean: Production Guide (Sinkamas)Documento2 pagineYam Bean: Production Guide (Sinkamas)Clifford Ryan Galenzoga100% (1)

- Bioaccumulation & BiomagnificationDocumento5 pagineBioaccumulation & BiomagnificationJR ZunigaNessuna valutazione finora

- Debit Andalan (FJ Mock) Pa AsmawarDocumento14 pagineDebit Andalan (FJ Mock) Pa AsmawarIkhbal MuttakinNessuna valutazione finora

- 04a Springer-Nature Ejournals Title-ListDocumento57 pagine04a Springer-Nature Ejournals Title-ListYaamini Rathinam K RNessuna valutazione finora

- Zimbabwe School Examinations Council Agriculture 4001/2Documento12 pagineZimbabwe School Examinations Council Agriculture 4001/2Lloyd Chris100% (2)

- What Is Biodiversity?: 1. Genetic DiversityDocumento4 pagineWhat Is Biodiversity?: 1. Genetic DiversityBella EstherNessuna valutazione finora

- 19 - Maximilian Veyne and CJ MartinDocumento8 pagine19 - Maximilian Veyne and CJ Martinapi-393403310Nessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 2 Cycle of MatterDocumento28 pagineCHAPTER 2 Cycle of MatterRamil NacarioNessuna valutazione finora

- KudzuDocumento6 pagineKudzuDonovan WagnerNessuna valutazione finora

- IPM Booklet For of-Dr.P.DDocumento56 pagineIPM Booklet For of-Dr.P.DPushparaj VigneshNessuna valutazione finora

- SystemsDocumento21 pagineSystemsFabian Fadull gutierrez100% (1)

- Intro Ecology NotesDocumento6 pagineIntro Ecology Notesapi-233187566Nessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Agriculture in India and Its ChallengesDocumento4 pagineUrban Agriculture in India and Its ChallengesSêlva AvlêsNessuna valutazione finora

- Designing Ecological Habitats EbookDocumento292 pagineDesigning Ecological Habitats EbookDaisy100% (4)

- Un Expository Essay Aidan DattadaDocumento4 pagineUn Expository Essay Aidan Dattadaapi-442460952Nessuna valutazione finora

- IB ESS Notes of CH #1 & CH #2Documento24 pagineIB ESS Notes of CH #1 & CH #2zwslpoNessuna valutazione finora

- DLP Science 6 Q2 W2 Day 5Documento5 pagineDLP Science 6 Q2 W2 Day 5Rubie Jane Aranda100% (1)

- Benefits and Harmful Interaction Among Living Things and Their EnvironmentDocumento31 pagineBenefits and Harmful Interaction Among Living Things and Their EnvironmentArdi Bernardo Olores100% (1)

- Plant EcologyDocumento22 paginePlant EcologyAtika ZulfiqarNessuna valutazione finora

- Fidelis & Zirondi (2021) - Floração CerradoDocumento7 pagineFidelis & Zirondi (2021) - Floração CerradorobertoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rural - Ecological Commons: Case of Pastures in İzmirDocumento241 pagineRural - Ecological Commons: Case of Pastures in İzmirRaziye İçtepeNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity of Life Through Time: Diversification of Life Patterns - Marine, Nonmarine, Vertebrates, PlantsDocumento7 pagineDiversity of Life Through Time: Diversification of Life Patterns - Marine, Nonmarine, Vertebrates, PlantsnareshNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Pop. Inter. (A)Documento10 pagineTest Pop. Inter. (A)kylevNessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Impact Assessment For Highway ProjectsDocumento8 pagineEnvironmental Impact Assessment For Highway Projectssaurabh514481% (32)

- 10 1111@gcb 14904Documento70 pagine10 1111@gcb 14904Ariadne Cristina De AntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- South East Asia Conference On Current Approaches To The Environmental Risk Assessment of Genetically Engineered CropsDocumento26 pagineSouth East Asia Conference On Current Approaches To The Environmental Risk Assessment of Genetically Engineered CropsDau NvNessuna valutazione finora

- Living Things in Their EnvironmentDocumento48 pagineLiving Things in Their EnvironmentEdwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Donana Waterand BiosphereDocumento366 pagineDonana Waterand BiosphereJosué Ochoa ParedesNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch.2.2 Ecological Pyramid WorksheetDocumento2 pagineCh.2.2 Ecological Pyramid Worksheet무루파털뭉치Nessuna valutazione finora