Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

C: R P G: Eripartum Ardiomyopathy Eview and Ractice Uidelines

Caricato da

Medika WisataTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

C: R P G: Eripartum Ardiomyopathy Eview and Ractice Uidelines

Caricato da

Medika WisataCopyright:

Formati disponibili

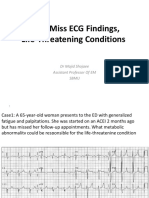

C ardiovascular Critical Care

P ERIPARTUM

CARDIOMYOPATHY:

REVIEW AND PRACTICE

GUIDELINES

By Leah Johnson-Coyle, RN, MN, Louise Jensen, RN, PhD, and Alan Sobey, MD

Peripartum cardiomyopathy, a type of dilated cardiomyopathy

of unknown origin, occurs in previously healthy women in the

final month of pregnancy and up to 5 months after delivery.

Although the incidence is lowless than 0.1% of pregnancies

morbidity and mortality rates are high at 5% to 32%. The

outcome of peripartum cardiomyopathy is also highly variable.

For some women, the clinical and echocardiographic status

improves and sometimes returns to normal, whereas for oth-

ers, the disease progresses to severe cardiac failure and even

sudden cardiac death. In acute care, treatment may involve

the use of intravenous vasodilators, inotropic medications, an

intra-aortic balloon pump, ventricular-assist devices, and/or

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Survivors of peripartum

cardiomyopathy often recover from left ventricular dysfunction;

however, they may be at risk for recurrence of heart failure

and death in subsequent pregnancies. Women with chronic

left ventricular dysfunction should be managed according to

guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation

2012 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

and the American Heart Association. (American Journal of

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2012163

Critical Care. 2012;21(2):89-98)

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 89

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

P

eripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a type of dilated cardiomyopathy of unknown

origin. It occurs in previously healthy women in the final month of pregnancy and

up to 5 months after delivery.1 Although the incidence is lowless than 0.1% of

pregnanciesmorbidity and mortality rates are high, ranging from 5% to 32%.2,3

For some women, the clinical and echocardiographic status improve and may

return to normal, whereas for others, PPCM progresses to cardiac failure and even sudden

cardiac death.4 In severe cases, women experience a rapid deterioration in health, show no

improvement with medical therapy, and may require cardiac transplantation or die of heart

failure, thromboembolic events, and/or cardiac arrhythmias.5 Thus, initial severity of left ven-

tricular dysfunction or dilatation is not necessarily predictive of long-term functional outcome.5

In this article, we review PPCM and present guidelines for practice.

Epidemiology that African American women were 2.9 times more

The reported incidence of PPCM varies because likely to have PPCM than were white women and 7

the diagnosis is not always consistent and a com- times more likely than were Hispanic women. The

parison with age-matched nonpregnant women does greater incidence of hypertension in African Ameri-

not exist.4,6,7 Reported incidences range from 1 in cans may influence this finding.4,7

299 live births in Haiti8 to 1 in 2229 live births in

Southern California9 to 1 in 4000 live births in the Etiology

United States.4 The wide variation most likely is the PPCM is distinguished from other forms of

result of geographic differences and cardiomyopathies by its occurrence during preg-

Initial severity reporting patterns.10 Also, limited access nancy.16 Precise mechanisms that lead to PPCM

to echocardiography in some areas remain poorly defined. Many etiological processes

of left ventricular may lead to overestimation of PPCM.11 have been suggested: viral myocarditis, abnormal

immune response to pregnancy, maladaptive response

dysfunction is Several risk factors predispose a

woman to PPCM, including increased to hemodynamic stresses of pregnancy, stress-activated

not necessarily maternal age, multiparity, multiple cytokines, excessive prolactin excretion, and pro-

pregnancies, and pregnancies compli- longed tocolysis.4,10,17,18 Also, a familial predisposition

predictive of cated by preeclampsia and gestational to PPCM has been reported.19-21 Although underly-

long-term outcome. hypertension.4,6,12 Although PPCM ing genetic variants common to dilated cardiomy-

occurs more frequently in women at opathies are being proposed,22 a genetic basis specific

the upper and lower extremes of child-bearing ages to PPCM has not been systematically studied.23 The

and in older women of higher parity,4,13 the disease European Society of Cardiology currently classifies

has also been reported in 24% to 37% of young PPCM as a nonfamilial, nongenetic form of dilated

primigravid women.3,6,14 In contrast, the results of a cardiomyopathy.24

large population-based study from Haiti suggested

that multiparity and increasing maternal age are not Viral Myocarditis

risk factors.8 Demakis et al12 and Brar et al15 found Viral myocarditis has been proposed as the main

mechanism for PPCM and was first reported by

Goulet et al.25 This proposal was later supported by

About the Authors Melvin et al,26 who found myocarditis during endomy-

Leah Johnson-Coyle is a nurse practitioner in cardiac ocardial biopsy in 3 women with PPCM. The biopsy

sciences and Alan Sobey is an intensive care physician specimens had dense lymphocytic infiltration with

in the cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit at the

Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, University of Alberta

a variable amount of myocytic edema, necrosis, and

Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Louise Jensen is fibrosis. Others27 have also reported an association

a professor in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of between PPCM and viral myocarditis. In a study by

Alberta in Edmonton.

Felker et al,28 62% of women with PPCM had

Corresponding author: Louise Jensen, RN, PhD, Professor, myocarditis or borderline myocarditis on biopsy;

Faculty of Nursing, 3rd Floor, Edmonton Clinic Health

Academy, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada however, clinical outcomes did not differ between

T6G 1C9 (e-mail: louise.jensen@ualberta.ca). women with and without myocarditis.

90 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Abnormal Immune Response erythropoietin, and hence hematocrit levels.18 Hil-

An abnormal immune response to fetal micro- fiker-Kleiner et al31 discovered that PPCM develops

chimerism (harboring of fetal cells in maternal cir- in mice bred to have a cardiomyocyte-specific dele-

culation) has been studied as a cause for PPCM.29 tion of STAT3, a protein that plays a key role in

Other researchers4,6,16,18 support this theory that dur- many cellular processes such as cell growth and

ing pregnancy fetal cells released into the maternal apoptosis. The deletion of STAT3 led to enhanced

bloodstream are not rejected by the mother because expression of cardiac cathepsin D, promoting the

of the natural immunosuppresion that occurs dur- formation of a 16-kD form of prolactin. In women

ing pregnancy. However, after delivery, women lose with PPCM, STAT3 protein levels were low in the

the increased immunity, and if fetal cells reside on heart, and serum levels of activated cathepsin D

cardiac tissue when the fetus is delivered, a patho- and 16-kD prolactin were elevated.16,31

logical autoimmune response can occur, leading to

PPCM in the mother after birth. Selenium and Malnutrition

Nutritional disorders, such as deficiencies in

Abnormal Hemodynamic Response selenium and other micronutrients, were thought

During pregnancy, blood volume and cardiac to play a role in the pathogenesis of PPCM.12,26 Defi-

output increase.4 In addition, afterload decreases ciencies of selenium increase cardiovascular suscep-

because of relaxation of vascular smooth muscle.13 tibility to viral infections, hypertension, and

These changes cause a brief, and reversible, hyper- hypocalcemia. However, Fett et al32 concluded that

trophy of the left ventricle to meet the needs of the neither low serum levels of selenium nor deficien-

mother and fetus.2 This transient left ventricular cies of other micronutrients (vitamins A, B12, C, E,

dysfunction during the third trimester and early and b-carotene), played a significant role in the

postpartum period resolves shortly after birth in a development of PPCM in Haitian women. In con-

normal pregnancy.2,18 Pearson et al4 suggested that trast, women with PPCM from the

PPCM might be due, in part, to an exaggerated

decrease in left ventricular function when these

Sahelian region of Africa had low

levels of selenium.33

Viral myocarditis

hemodynamic changes of pregnancy occur. has been

Prolonged Tocolysis

Apoptosis and Inflammation Prolonged tocolysis refers to

proposed as the

An increased concentration of plasma inflamma- the use of tocolytic agents (b-sym- main mechanism

tory cytokines, specifically tumor necrosis factor a; pathomimetic drugs) for more

C-reactive protein; and Fas/Apo-1, a plasma marker than 4 weeks.18 The association for peripartum

for apoptosis (programmed cell death), have been between tocolytic therapies and cardiomyopathy.

identified in women with PPCM.3 Levels of Fas/Apo-1, heart failure appears to be unique

a ligand found on cell-surface proteins that plays a to pregnancy. Tocolytic agents are used for the man-

key role in apoptosis, were higher in women with agement of various other conditions without the

PPCM than in healthy volunteers.3 Furthermore, these occurrence of signs and symptoms of heart failure

Fas/Apo-1 levels were higher among women with like those experienced by pregnant women. Such

PPCM who died than among those with PPCM who signs and symptoms may develop in pregnant

survived. However, a correlation between increased women as a result of normal physiological changes

plasma cytokine levels and left ventricular function that occur, including an increase in circulating

or outcomes has not been demonstrated. Van Hoeven blood volume.18 Lampert et al34 found an associa-

et al30 further concluded that ejection fraction at the tion between use of tocolytic therapies and develop-

time of clinical findings suggestive of PPCM was the ment of pulmonary edema in pregnant women and

strongest predictor of outcome. proposed a link between chronic use of b-sympath-

omimetic medications and PPCM.

Prolactin

Hilfiker-Kleiner et al16,31 have proposed a new Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

pathogenic mechanism for PPCM: excessive pro- Features of a normal pregnancy include increased

lactin production. Levels of prolactin are associated blood volume, increased metabolic demands, mild

with increased blood volume, decreased blood anemia, changes in vascular resistance associated

pressure, decreased angiotensin responsiveness, and with mild ventricular dilatation, and increased car-

a reduction in the levels of water, sodium, and potas- diac output.11 Thus, the onset of PPCM can easily be

sium.31 Prolactin also increases the level of circulating maskedand missedbecause the manifestations

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 91

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

can mimic those of mild heart failure. Women with left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-T wave abnormalities,

PPCM most commonly have dyspnea, dizziness, dysrhythmias, Q-waves in the anteroseptal precor-

chest pain, cough, neck vein distension, fatigue, dial leads, and prolonged PR and QRS intervals.4,38

and peripheral edema.4,10,13 Women can also have Several laboratory tests should be performed: com-

arrhythmias, embolic events due to the dilated, plete blood cell counts and serum levels of troponin,

dysfunctional left ventricle, and acute myocardial urea, creatinine, and electrolytes.11,20 Liver function

infarction due to decreased perfusion to the coronary tests should be done, and levels of thyroid-stimulat-

arteries.4,10,35 They can also have other indications ing hormone should be measured. In the initial

typical of heart failure: hypoxia, jugular venous dis- evaluation, the serum level of troponin may be

tention, S3 and S4 gallop, rales, and hepatomegaly.35 helpful in ruling out myocardial infarction; how-

Blood pressure is often normal or decreased, and ever an increase in troponin in the acute phase of

tachycardia is common.20 PPCM, without myocardial infarction, can occur.35

PPCM was first defined in 1971 as the develop- Levels of B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal

ment of myocardial disease that occurs for the first pro-B-type natriuretic peptide can help in confirm-

time toward the end or in the early stage of the ing the diagnosis.38,39

pregnancy.12 A modification of this classic definition Unlike pulmonary artery catheterization,

added a strict echocardiographic crite- echocardiography is noninvasive and allows serial

rion.1 The National Heart, Lung, and evaluations in pregnant women.1 Serial echocardio-

Magnetic Blood Institute and the Office of Rare graphy with Doppler imaging is used to evaluate

resonance images Diseases workshop adopted the modi- and monitor regional and global left and right ven-

fied definition in 2000.4 In 2010, the tricular function, valvular structure and function,

can be used to European Society of Cardiology Work- possible pericardial pathological changes, and

ing Group on Peripartum Cardiomy- mechanical complications.11 Findings in women

measure global opathy36 proposed a modification to with PPCM are consistent with the findings in heart

and segmental the existing definition of PPCM. PPCM failure: decreased ejection fraction, global dilata-

is defined as an idiopathic cardiomy- tion, and thinned-out cardiac walls.4,11,38

contraction and opathy manifested as heart failure due Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging has been

identify inflamma- to left ventricular systolic dysfunction suggested as a complementary tool in the diagnosis

toward the end of pregnancy or in the and evaluation of women with PPCM.13,21,30 Such

tory processes. months after delivery when no other imaging can be used to measure global and seg-

cause of heart failure is found. Thus, mental myocardial contraction, can help in charac-

PPCM is a diagnosis of exclusion, suggesting that a terizing the pathogenesis of the disease, and can

broader definition would eliminate PPCM as a reveal inflammatory processes.13 Baruteau et al21

missed diagnosis.36 maintain that because cardiac magnetic resonance

The definitive diagnosis of PPCM depends on imaging can be used to distinguish inflammatory

echocardiographic identification of new-onset heart from noninflammatory pathogenesis, it can be

failure during a limited period around parturition. helpful at the initial evaluation of a woman with

A diagnosis of PPCM requires the exclusion of other PPCM to determine the pathophysiology and to

causes of heart failure: myocardial infarction, sepsis, guide further therapeutic options. Ntusi and Chin40

severe preeclampsia, pulmonary embolism, valvular disagree, however, and do not see a benefit for

diseases, and other forms of cardiomyopathy.17,37 obtaining cardiac magnetic resonance images in all

Chest radiographs should be obtained in sus- women who have PPCM. Guidelines for diagnosis

pected cases of PPCM.35 Chest radiographs may be of PPCM according to the American College of Car-

helpful in acute pulmonary edema, but much less diology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart

so if no clinical evidence of pulmonary congestion Association (AHA)39 are provided in Figures 1 and 2.

is revealed. Radiological indications of heart failure

such as cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and Management

pleural effusions may be evident.35 However, diag- Compensated Heart Failure

nosing cardiomegaly on the basis of a chest radi- Management of PPCM is similar to standard

ograph in a pregnant patient is difficult because treatment for other forms of heart failure.4,39,41 How-

the heart is pushed upward and laterally, giving the ever, no randomized clinical trials have been done

false impression of cardiomegaly. to evaluate these therapies specifically in PPCM.

Electrocardiograms should also be obtained. In Furthermore, careful attention should be paid to fetal

PPCM, the tracings may be normal or may show safety and to excretion of drug or drug metabolites

92 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Woman with signs and symptoms of heart failure who is

during breastfeeding after delivery.4 The goals in

In last month of pregnancy or

treating heart failure are to improve hemodynamic

Within 5 months postpartum

status, minimize signs and symptoms, and optimize

the long-term outcomes. Treatment focuses on

reducing preload and afterload and increasing car-

diac inotropy.2,4,35 Pearson et al4 reinforce that col-

laboration among medical specialists, including Signs and symptoms of heart failure

obstetricians, cardiologists, perinatologists, and

Dyspnea Cough

neonatologists, is essential in care of women with

Fatigue (at rest or exertion) Heart palpitations/tachycardia

PPCM. Of note, polypharmacy may be required for Neck vein distention Sudden weight gain, fluid retention

optimal management, to slow progression of heart Exercise intolerance Arrhythmias

failure and to improve outcomes in women with left Peripheral edema Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

ventricular systolic dysfunction.42 Medications should Weight gain (water retention) Hepatomegaly

Chest pain Weakness

be continued until evidence indicates improved

and/or resolved left ventricular dysfunction.4,35

Women with PPCM should be treated in the hospital

when they have evidence of hypotension, worsening

heart failure, altered mental status, and increased Diagnostic testing

work of breathing.42

Complete family history, to identify possible familial association

Preload reduction is accomplished by adminis- Serum tests

tration of vasodilators, such as nitrates, most of Complete blood cell count with differential

which are safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding.35 Creatinine and urea levels

Loop diuretics are important for management of Electrolyte levels, including magnesium and calcium

signs and symptoms and for preload reduction, Levels of cardiac enzymes, including troponin

Level of B-type natriuretic peptide and/or N-terminal

although caution is warranted in antepartum women pro-B-type natriuretic protein

because rapid changes in intravascular volume can Liver function and level of thyroid-stimulating hormone

lead to a decrease in blood supply to the uterus and Chest radiograph

therefore the fetus.35,43 Restriction of dietary sodium Electrocardiogram

is also helpful in preload reduction.2 Bed rest was Transthoracic echocardiogram

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and/or endomyocardial

once standard care but is no longer recommended biopsy (when indicated)

because of the increased risk of thromboembolism.20

The current recommendation is light exercise such

as walking.4,10 Figure 1 Evaluation of peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Ideal medications intrapartum include hydrala-

zine, nitrates, digoxin, and diuretics. Angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitors are contraindicated after more than 2 weeks of therapy. Digoxin, an

during pregnancy because of their teratogenicity, inotropic agent, is also safe during pregnancy and

but these medications are the mainstay of treatment should be considered for women with left ventricu-

of PPCM after delivery for afterload reduction.4,13,38 lar systolic dysfunction and an ejection fraction of

Safe alternatives during pregnancy include hydrala- less than 40% who have signs and symptoms of

zine and nitrates.4,10 Aldosterone antagonists have heart failure while receiving standard therapy.42

been effective when angiotensin-converting enzyme Guidelines for management of compensated heart

inhibitors were not tolerated, but the antagonists failure in PPCM are presented in Table 1.

should not be used during pregnancy.41

b-Adrenergic antagonists, such as extended-release Decompensated Heart Failure

metoprolol and carvedilol, have been approved for In pregnant women with acute decompensat-

use in PCCM and can improve survival.4,20,43 How- ing heart failure, management begins with the

ever, b-blockers should not be given in the early ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation).35 Assessment

stages of PPCM because they can decrease perfusion of the airway is critical because pregnancy or recent

in the acute decompensated phase of the disease.35 pregnancy with associated third spacing of excess

Pearson et al4 have proposed that carvedilol be used intravascular volume can result in a suboptimal air-

in postpartum women who continue to have signs way.35 Women with impending respiratory failure

and symptoms of heart failure and have echocardio- from pulmonary edema require rapid initiation of

graphic evidence of left ventricular compromise supported ventilation.44 Endotracheal intubation is

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 93

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Diagnostic criteria for peripartum cardiomyopathy

All 4 of the following:

In antepartum women, fetal heart rate monitor-

ing should be started early because abnormalities in

Classic

fetal heart rate tracings are common when maternal

1. Development of cardiac failure in the last month of pregnancy or

within 5 months postpartum oxygenation and circulation are compromised.35 Med-

2. No identifiable cause for the cardiac failure ical stabilization of the mothers condition is critical

3. No recognizable heart disease before the last month of and may result in resolution of fetal distress and pre-

pregnancy vent the need for emergency cesarean delivery that

Additional most likely would be poorly tolerated by the mother.35

1. Strict echocardiographic indication of left ventricular dysfunction: Women with acute heart failure benefit from

a. Ejection fraction <45% intravenous administration of positive inotropic

and/or

b. Fractional shortening <30%

agents such as dobutamine and milrinone, none of

c. End-diastolic dimension >2.7 cm/m2 which are contraindicated in pregnancy.44 Positive

inotropic agents improve cardiac performance, facil-

itate diuresis, preserve end-organ function, and pro-

mote clinical stability.13,17,39 Dobutamine requires

No: Consider other cause Yes: Meets criteria for b-receptors for its inotropic effects, whereas milrinone

diagnosis for peripartum does not, an important distinction in planning care

cardiomyopathy for a patient who is being treated with b-blocking

drugs.39 Furthermore, milrinone has vasodilating

properties for both the systemic and the pulmonary

circulation, a mechanism that may be a marked

benefit over other inotropic agents. In women with

Consultation with cardiologist, obstetrician, perinatologist

systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, dobut-

If diagnosis is made before the woman gives birth: involve amine may be preferred over milrinone.44 Vasodilatory

anesthesiology and neonatology also, and consider transfer to

drugs such as nitroglycerin and nitroprusside also

a high-risk perinatal center

may be of benefit.35,39 Nitroprusside should be used

with caution in pregnant women because the toxic

Figure 2 Diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy. effects of thiocyanate can be harmful to the fetus.20,42

Based on Pearson et al4 and Sliwa et al.36 Clinicians should not focus therapy on a spe-

cific blood pressure value that might or might not

indicate hypotension; rather, they should focus on

often required; however, attempts involving nonin- signs and symptoms associated with poor cardiac

vasive ventilation may obviate intubation.44 Nonin- output and hypoperfusion, such as cold clammy

vasive ventilation must be used with caution because skin, cool upper and lower extremities, decreased

of the high risk for aspiration. Breathing is supported urine output, and altered mental status.39 Inotropic

with supplemental oxygen to relieve signs and symp- agents are of greatest value in women who have

toms related to hypoxemia and is assessed via con- relative hypotension and an intolerance or no

tinuous pulse oxymetry. Women should have cardiac response to vasodilators and diuretics.42 Regardless,

monitoring, including ST-segment monitoring when if invasive monitoring of hemodynamic status is

available.13,35 Blood pressure should be monitored used, once the clinical status of the woman has

with noninvasive blood pressure cuffs until arterial stabilized, every effort should be made to devise an

catheters are placed. Venous and arterial access oral regimen that can maintain symptomatic improve-

should be obtained early so that medications can ment and reduce the subsequent risk of any deterio-

be administered promptly and monitoring can be ration in her condition.42

streamlined.35 Some clinicians39 advocate for the use Left ventricular thrombus is common in women

of pulmonary artery catheters in women whose heart with PPCM whose ejection fraction is less than

failure is refractory; however, this logic has been 35%.2,38 Warfarin should be given to postpartum

questioned because many of the drugs used to treat women whose ejection fraction is 35% or less, and

PPCM produce benefits by mechanisms that cannot heparin or a low-molecular-weight heparin should

be assessed by measurement of short-term changes be given to women who are pregnant and have a

in hemodynamic status. Pulmonary artery catheters similar ejection fraction.20,35 Anticoagulation therapy

may be beneficial in patients with heart failure, but should be continued until left ventricular function

little information is available on their use in is normal according to echocardiographic find-

women with PPCM. ings.13,39 Arrhythmias should be aggressively treated

94 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Table 1 Management of compensated heart failure in peripartum

cardiomyopathya

to minimize thrombus formation and to optimize

cardiac function.4,10 Nonpharmaceutical therapies

Immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory Low-sodium diet: limit of 2 g sodium per day

therapies have not improved the outcome in PPCM Fluid restriction: 2 L/day

and, in general, are not recommended.45 Because of Light daily activity: if tolerated (eg, walking)

the various mechanisms of PPCM, immunosuppre- Oral pharmaceutical therapies

sion most likely would not help all women.13,35,45

Antepartum management of peripartum cardiomyopathy

b-blocker

In a case report, Jahns et al46 stated that bromo-

criptine, a dopamine antagonist that inhibits pro- Carvedilol (starting dose 3.125 mg twice a day, target dose

lactin secretion, prevented the expected deterioration 25 mg twice a day)

in the size of the left ventricle and systolic function Extended-release metoprol (starting dose 0.125 mg daily, target

when given in addition to standard heart failure dose 0.25 mg daily)

therapy in a woman with PPCM. The treatment of Vasodilator

STAT3-deficient mice with bromocriptine also pre- Hydralazine (starting dose 10 mg 3 times a day, target dose 40 mg

3 times a day)

vented the development of PPCM in a study by

Hilfiker-Kleiner et al.16 The results of assessments of Digoxin (starting dose 0.125 mg daily, target dose 0.25 mg daily)

the therapeutic effects of prolactin blockade with Monitor serum levels

bromocriptine are promising, and trials are being Thiazide diuretic (with caution)

done in women with PPCM.16,31 In a case study, de Hydrochlorothiazide (12.5-50 mg daily)

Jong et al47 argue that the benefit of using cabergo- May also consider loop diuretic with caution

line, another potent dopamine receptor antagonist Low-molecular-weight heparin if ejection fraction <35%

like bromocriptine, is the long half-life, 14 to 21

Postpartum management of peripartum cardiomyopathy

days, of cabergoline, so a single dose is often enough. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor

Medical therapy can be unsuccessful in women Captopril (starting dose 6.25-12.5 mg 3 times a day,

with PPCM, and mechanical cardiovascular support target dose 25-50 mg 3 times a day)

with an intra-aortic balloon pump or ventricular Enalapril (starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg 2 times a day,

assist devices may be required.48,49 Left ventricular target dose 10 mg 2 times a day)

Ramipril (starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg 2 times a day,

assist devices can be a bridge to recovery or to trans- target dose 5 mg 2 times a day)

plantation.13,49-51 Use of short-term extracorporeal Lisinopril (starting dose 2.5-5 mg daily, target dose

membrane oxygenation has also been of benefit in 25-40 mg daily)

women with PPCM whose heart failure was refrac- Angiotensin-receptor blocker (if ACE inhibitor not tolerated)

tory to medical therapy and who had persistent pul- Candesartan (starting dose 2 mg daily, target dose 32 mg daily)

Valsartan (starting dose 40 mg twice a day, target dose 160 mg

monary edema with hypoxemia.48,50 Extracorporeal twice a day)

membrane oxygenation can also serve as a bridge

Consider nitrates or hydralazine if woman is intolerant to ACE

to left ventricular assist devices in patients with

inhibitor and angiotensin-receptor blocker

refractory cardiogenic shock despite use of an intra-

aortic balloon pump and full inotropic support.51 Loop diuretic

Furosemide intravenously or by mouthdosing considerations

Women in whom maximal medical manage- should be made on the basis of creatinine clearance

ment is unsuccessful may be candidates for cardiac Glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min per 1.73 m2:

transplantation.48 According to one study,14 cardiac furosemide 20-40 mg every12-24 h

transplantation was necessary in 4% of women with Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2:

PPCM. In another study52 in which 69 women under- furosemide 20-80 mg every 12-24 h

Vasodilator

went cardiac transplantation for PPCM, the investi- Hydralazine (starting dose 37.5 mg 3 or 4 times a day, target dose

gators concluded that heart transplantation is a 40 mg 3 times a day)

practical therapeutic option for women with PPCM Isorbide dinitrate (starting dose 20 mg 3 times a day, target dose

who have advanced heart failure and signs and 40 mg 3 times a day)

symptoms unresponsive to medical therapies. The Aldosterone antagonist

Spironolactone (starting dose 12.5 mg daily, target dose

risk of organ rejection in women with PPCM does 25-50 mg daily)

not appear to be higher than the risk in women of Eplerenone (starting dose 12.5 mg daily, target dose 25-50 mg daily)

similar age who have a history of pregnancy and b-blocker as above

undergo transplantation for other causes. However, Warfarin if ejection fraction <35%

in an earlier study, Koegh et al48 found that the inci-

dence of biopsy-proven early rejection, necessitating aBased in part on Jessup et al39 and Heart Failure Society of America.42

increased cytolytic therapy, was marginally higher in

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 95

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Table 2 Management of decompensated heart failure in

peripartum cardiomyopathya

Airway women with PPCM than in women with dilated

Intubate promptly upon distress for increased work of breathing cardiomyopathy. Table 2 presents guidelines for man-

to prevent complications with difficult airway later in treatment agement of decompensated heart failure in PPCM.

Breathing

Provide supplemental oxygen

Maintain continuous pulse oximetry to monitor SaO2

Outcomes of PPCM

Measure arterial blood gases (if available) every 4-6 h until Prognosis of PPCM is positively related to the

breathing is stable recovery of ventricular function.17 Failure of heart

Circulation size to return to normal is associated with increased

Start cardiac and blood pressure monitoring mortality and morbidity.4 Women with persistent

Insert arterial catheter for accurate blood pressure monitoring

left ventricular dysfunction are less likely to survive

and blood sampling

Obtain central venous access with central venous pressure and recover normal cardiac function than are women

monitoring with improved left ventricular function. A fractional

In antepartum women, obtain fetal monitoring shortening less than 20% and a left ventricular

Pharmacological management of acute heart failure in peripartum diastolic dimension of 6 cm or greater at the time

cardiomyopathy of diagnosis are associated with a more than 3-fold

Intravenous loop diuretic (caution is advised in antepartum higher risk for persistent cardiac dysfunction.53

women) Sliwa et al3 found that ejection fraction was the

Furosemide: dosing considerations should be made on the strongest predictor of outcome in women with PPCM.

basis of creatinine clearance Abboud et al17 reported that 50% of women with

Glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min per 1.73 m2:

PPCM recover baseline ventricular function within

furosemide 20-40 mg intravenously every 12-24 h

Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2: 6 months of delivery. In contrast, Ntusi and Mayosi18

furosemide 20-80 mg intravenous every12-24 h found that only 30% of women with PPCM have

In severe fluid overload, consider furosemide infusion or complete recovery of cardiac function; most have

ultrafiltration partial recovery. Medical therapy as outlined in the

Vasodilator

ACCF/AHA guidelines39 should be continued when

Nitroglycerin infusion 5-10 g/min, titrate to clinical status and

blood pressure a woman does not recover function. When appropri-

Nitroprusside 0.1-5 g/kg per minute, use with caution in ate, implantation of defibrillators to prevent sudden

antepartum women cardiac death and use of cardiac revascularization

Positive inotropic agents therapy should be considered.

Milrinone 0.125-0.5 g/kg per minute Reported mortality rates for PPCM vary widely.

Dobutamine 2.5-10 g/kg per minute In a study by Sliwa et al,3 the mortality rate in 29

Avoid b-blockers in the acute phase, as they can decrease perfusion women was 32%, whereas in a large population-

Heparin sodium, alone or with oral warfarin (Coumadin) therapy based study in Haiti by Fett et al,8 the mortality rate

Monitor oxygenation with arterial blood gases every 4-6 h until was 15.8%. In a study of 123 women by Elkayam

patients condition is stable

et al,5 the rate was 9% at a mean follow-up time of

Consider endomyocardial biopsy; if proven viral myocarditis,

consider immunosuppresive medications (eg, azathioprine, 24 months. Brar et al15 concluded that mortality

corticosteroids) rates associated with PPCM were lower than initially

Every effort should be made to devise an oral regimen that can

reported at 2.5%, and Mielniczuk et al9 reported a

maintain symptomatic improvement and reduce the subsequent mortality rate of 1.36% to 2.05%. Earlier diagnosis,

risk of worsening clinical status coupled with modern management of heart failure,

most likely has an important influence on the mor-

tality associated with PPCM.9,15 Although rates have

If no improvement clinically:

improved, mortality remains extremely high in

Consider cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Perform endomyocardial biopsy to detect viral myocarditis women with PPCM.

(if not previously completed) One of the most frequently cited issues for

Assist devices: women who survive PPCM is whether or not they

Intra-aortic balloon pump can safely become pregnant again.5,14 No clearly

Left ventricular assist devices established recommendations for future pregnancies

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in these women exist.20 Left ventricular recovery and

Transplantation

function are considered the most reliable prognostic

If a woman remains refractory to therapy, consult your institutions factors and predictors of survival in subsequent

guidelines for bromocriptine or cabergoline administration for pregnancies.20 Future pregnancies are not recom-

suppression of prolactin production

mended in women with persistent heart failure,

aBased in part on Jessup et al39 and Heart Failure Society of America.42 because the heart most likely would not be able to

96 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

tolerate the increased cardiovascular workload asso- FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

None reported.

ciated with the pregnancy.5,13 Women whose car-

diomyopathy appears to have resolved are a more

REFERENCES

difficult group to counsel.4 Because multiparity has 1. Hibbard JU, Lindheimer M, Lang RM. A modified definition

been associated with PPCM, subsequent pregnan- for peripartum cardiomyopathy and prognosis based on

echocardiography. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;4(2):311-315.

cies can increase the risk for recurrent episodes of 2. Tidswell M. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Crit Care Clin.

PPCM, irreversible cardiac damage and decreased 2004;20:777-788.

3. Sliwa K, Skudicky D, Bergemann A, Candy G, Puren A,

left ventricular function, worsening of a womans Sareli P. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: analysis of clinical

clinical condition, and even death.4,14 outcome, left ventricular function, plasma levels of cyto-

kines and Fas/APO-1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):701-705.

Williams et al35 have suggested that dividing 4. Pearson G, Veille J, Rahimtoola S, et al. Peripartum car-

women into 2 categories (recovered vs nonrecovered diomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health)

left ventricular function) is most appropriate for workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283(9):

counseling on future pregnancy. Even though the 1183-1188.

5. Elkayam U, Tummala PP, Rao K, et al. Maternal and fetal out-

cardiac function has normalized in the group of comes of subsequent pregnancies in women with peripartum

women with recovered cardiac function, the left cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1567-1571.

6. Sliwa K, Fett J, Elkayam U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy.

ventricular contractile reserve may remain impaired, Lancet. 2006;368(9536):687-693.

and recurrence of PPCM is still possible.4,5 The sub- 7. James P. A review of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Clin

Pract. 2004;58(4):363-365.

set of women with persistent left ventricular systolic 8. Fett JD, Christie LG, Carraway RD, Murphy JG. Five-year

dysfunction should be counseled against subse- prospective study of the incidence and prognosis of peri-

partum cardiomyopathy at a single institution. Mayo Clin

quent pregnancies; the risks are 19% higher for Proc. 2005;80(12):1602-1606.

maternal death than among women with PPCM 9 Mielniczuk LM, Williams K, Davis DR, et al. Frequency of

peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(12):

whose heart failure has resolved.35 1765-1768.

10. Ro A, Frishman W. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Cardiol

Rev. 2006:14(1):35-42.

Conclusion 11. Sliwa K, Tibazarwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D. Management of

PPCM affects previously healthy women in the peripartum cardiomyopathy. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2008;5(5):

238-244.

final month of pregnancy and up to 5 months after 12. Demakis JG, Rahimtoola S, Sutton GC, et al. Natural course

delivery.4 The diagnosis is based on 4 criteria.1,4 For of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1971;44(6):

1053-1061.

some women, the clinical and echocardiographic 13. Ramaraj R, Sorrell VL. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: causes,

status improve rapidly and sometimes return to diagnosis, and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(5):

289-296.

normal. In other women, the clinical condition rap- 14. Elkayam U, Akhter MW, Singh H, et al. Pregnancy-associated

idly worsens, no improvement occurs with medical cardiomyopathy: clinical characteristics and a comparison

between early and late presentation. Circulation. 2005;111

therapy, and chronic heart failure from persistent (16):2050-2055.

ventricular dysfunction develops.5 No single expla- 15. Brar SS, Khan SS, Sandhu GK, et al. Incidence, mortality,

and racial differences in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am

nation of the pathogenesis of PPCM is relevant for J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):302-304.

all women; the disease has a multifactorial origin. 16. Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Sliwa K, Drexler H. Peripartum cardiomy-

opathy: recent insights in its pathophysiology. Trends Car-

In acute care, treatment may involve the use of diovasc Med. 2008;18(5):173-179.

intravenous vasodilators, inotropic medications, an 17. Abboud J, Murad Y, Chen-Scarabelli C, Saravolatz L,

Scarabelli TM. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a comprehen-

intra-aortic balloon pump, ventricular assist devices, sive review. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118(3):295-303.

and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.20,50 18. Ntusi NB, Mayosi BM. Aetiology and risk factors of peripar-

tum cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol.

Survivors of PPCM often recover from left ventricu- 2009;131(2):168-179.

lar dysfunction; however, they may be at risk for 19. Pearl W. Familial occurrence of peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Am Heart J. 1995;129(2):421-422.

recurrence of heart failure and death in subsequent 20. Moioli M, Menada MV, Bentivoglio G, Ferrero S. Peripartum

pregnancies. Women with chronic left ventricular cardiomyopathy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(2):183-188.

doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1170-5.

dysfunction should be managed according to 21. Baruteau AE, Leurent G, Martins R, et al. Peripartum car-

ACCF/AHA guidelines.39 Careful assessment of risk diomyopathy in the era of cardiac magnetic resonance

imaging: first results and perspectives. Int J Cardiol. 2010;

factors in pregnant women could help in the preven- 144(1):143-145.

tion of PPCM. Tools to stratify women by risk who 22. van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Tintelen P, van Veldhuisen

DJ, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy as a part of familial

have recovered from PPCM are needed to predict dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;121:2169-2175.

the risk of future pregnancies. 23. Burkett EL, Hershberger RE. Clinical and genetic issues in

familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;

45(7):969-981.

24. Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of

eLetters the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the Euro-

Now that youve read the article, create or contribute to an pean Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial

online discussion on this topic. Visit www.ajcconline.org and Pericardial Disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(2):270-276.

and click Submit a response in either the full-text or 25. Goulet B, McMillan T, Bellet S. Idiopathic myocardial degen-

PDF view of the article. eration associated with pregnancy and especially the puer-

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 97

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

pernium. Am J Med Sci. 1937;194(2):185-199. 40. Ntusi NB, Chin A. Characterisation of peripartum cardiomy-

26. Melvin KR, Richardson PJ, Olsen EG, Daly K, Jackson G. opathy by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy due to myocarditis. N Engl J 2009;19(6):1324-1325.

Med. 1982;307(12):731-734. 41. Carlin AJ, Alfirevic Z, Gyte ML. Interventions for treating

27. Midei MG, DeMent SH, Feldman AM, Hutchins GM, Baugh- peripartum cardiomyopathy to improve outcomes for

man KL. Peripartum myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. women and babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(9):

Circulation. 1990;81:922-928. CD008589. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008589.pub2.

28. Felker GM, Jaeger CJ, Klodas E, et al. Myocarditis and 42. Heart Failure Society of America. Executive summary:

long-term survival in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am HFSA 2006 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline.

Heart J. 2000;140(5):785-791. J Card Fail. 2006;12(1):10-38.

29. Ansari AA, Fett JD, Carraway RE, Mayne AE, Onlamoon N, 43. Egan DJ, Bisanzo MC, Hutson HR. Emergency department

Sundstrom JB. Autoimmune mechanisms as the basis for evaluation and management of peripartum cardiomyopathy.

human peripartum cardiomyopathy. Clin Rev Allergy J Emerg Med. 2009;36(2):141-147.

Immunol. 2002;23:301-324. 44. Arnold JM, Liu P, Demers C, et al; Canadian Cardiovascular

30. van Hoeven KH, Kitsis RN, Katz SD, Factor SM. Peripartum Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society consensus con-

versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in young women ference recommendation on heart failure 2006: diagnosis

a comparison of clinical, pathological and prognostic fac- and management. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(1):23-45.

tors. Int J Cardiol. 1993;40(1):57-65. 45. McNamara DM, Holubkov R, Starling, RC, et al. Controlled

31. Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaminski K, Podewski E, et al. A cathepsin trial of intravenous immune globulins in recent-onset

D-cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:2254-2259.

cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2007;128(3):589-600. 46. Jahns BG, Stein W, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Pieske B, Emons G.

32. Fett J, Ansara A, Sundstrom J, Combs G Jr. Peripartum Peripartum cardiomyopathya new treatment option by

cardiomyopathy: a selenium disconnection and an autoim- inhibition of prolactin secretion. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

mune connection. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86(2):311-316. 2008;199(4):e5-e6.

33. Cnac A, Simonoff M, Moretto P, Djibo A. A low plasma 47. de Jong JS, Rietveld K, van Lochem LT, Bouma BJ. Rapid left

selenium is a risk factor for peripartum cardiomyopathy: a ventricular recovery after cabergoline treatment in a patient

comparative study in Sahelian Africa. Int J Cardiol. 1992; with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;1(2):

36(1):57-59. 220-222.

34. Lampert MB, Hibbard J, Weinert L, Briller J, Lindheimer M, 48. Keogh A, Macdonald P, Spratt P, Marshman D, Larbalestier R,

Lang RM. Peripartum heart failure associated with prolonged Kaan A. Outcome in peripartum cardiomyopathy after heart

tocolytic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;168(2):493-495. transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13(2):202-207.

35. Williams J, Mozurkewich E, Chilimigras J, Van De Ven C. 49. Smith IJ, Gillham MJ. Fulminant peripartum cardiomyopathy

Critical care in obstetrics: pregnancy-specific conditions. rescue with extracorporeal membranous oxygenation. Int

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(5):825-846. J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18(2):186-188.

36. Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Petrie MC, et al; Heart Failure 50. Palanzo DA, Baer LD, El-Banayosy A, et al. Successful treat-

Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working ment of peripartum cardiomyopathy with extracorporeal

Group on Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. Current state of membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2009;24(2):75-79.

knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and ther- 51. Gavaert S, van Belleghem Y, Bouchez S, et al. Acute and

apy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement critically ill peripartum cardiomyopathy and bridge to

from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society therapeutic options: a single center experience with intra-

of Cardiology Working Group on Peripartum Cardiomyopa- aortic balloon pump, extra-corporeal membrane oxygena-

thy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(8):767-778. tion and continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. Crit

37. Pyatt JR, Dubey G. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: current Care. 2011;15(2):R93.

understanding, comprehensive management review and 52. Rasmusson K, de Jong M, Doering L. Update on heart failure

new developments. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1023):34-39. management. current understanding of peripartum cardiomy-

38. Lata I, Gupta R, Sahu S, Singh H. Emergency management opathy. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(4):214-216.

of decompensated peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Emerg 53. Chapa JB, Heiberger HB, Weinert L, Decara J, Lang RM, Hib-

Trauma Shock. 2009;2(2):124-128. bard JU. Prognostic value of echocardiography in peripartum

39. Jessup M, Abraham W, Casey D, et al. 2009 Focused update: cardiomyopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1303-1308.

ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management

of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College

of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact The

Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656.

With the International Society for Heart and Lung Trans- Phone, (800) 899-1712 or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax,

plantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(15):1343-1382. (949) 362-2049; e-mail, reprints@aacn.org.

98 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, March 2012, Volume 21, No. 2 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: Review and Practice Guidelines

Leah Johnson-Coyle, Louise Jensen and Alan Sobey

Am J Crit Care 2012;21 89-98 10.4037/ajcc2012163

2012 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

Published online http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/

Personal use only. For copyright permission information:

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/cgi/external_ref?link_type=PERMISSIONDIRECT

Subscription Information

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/

Information for authors

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/misc/ifora.xhtml

Submit a manuscript

http://www.editorialmanager.com/ajcc

Email alerts

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/etoc.xhtml

The American Journal of Critical Care is an official peer-reviewed journal of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

(AACN) published bimonthly by AACN, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Telephone: (800) 899-1712, (949) 362-2050, ext.

532. Fax: (949) 362-2049. Copyright 2016 by AACN. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on May 8, 2017

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 2013 Aajm PPCMDocumento15 pagine2013 Aajm PPCMJaisyi UmamNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiomiopatia Periparto 2017Documento3 pagineCardiomiopatia Periparto 2017Gustavo Reyes QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Molecular Mechanism of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy A Vaskular or Hormonal HypothesisDocumento11 pagineMolecular Mechanism of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy A Vaskular or Hormonal HypothesisAnggi saputriNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy JACC State o - 2020 - Journal of The American CollegeDocumento15 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy JACC State o - 2020 - Journal of The American CollegeVivi DeviyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chinweuba, 2020Documento7 pagineChinweuba, 2020Karina PuspaseruniNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Profile and Outcome of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Among Teenager Patients at The University of The Philippines - Philippine General HospitalDocumento7 pagineClinical Profile and Outcome of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Among Teenager Patients at The University of The Philippines - Philippine General HospitalSheila Jane GaoiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiomyopathy and Pregnancy BMJDocumento9 pagineCardiomyopathy and Pregnancy BMJkarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2009 RAMARAJ 289 96Documento8 pagineCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2009 RAMARAJ 289 96Andi Farras WatyNessuna valutazione finora

- Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine: Kathleen Stergiopoulos, Fabio V. LimaDocumento10 pagineTrends in Cardiovascular Medicine: Kathleen Stergiopoulos, Fabio V. LimaHARBENNessuna valutazione finora

- Cvja 27 111Documento8 pagineCvja 27 111Jorge Luis AlvarezNessuna valutazione finora

- 428 FullDocumento12 pagine428 FullAyesha PeerNessuna valutazione finora

- P C - Peripartum CardiomyopathyDocumento1 paginaP C - Peripartum CardiomyopathyAryo Damar DjatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy MedscapeDocumento18 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy MedscapeAji Isra SaputraNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Article: Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Life Threatening Obstetric Emergency by D Zeba and R BiswasDocumento4 pagineReview Article: Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Life Threatening Obstetric Emergency by D Zeba and R BiswasRajib BiswasNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: An Obstetric Review: Priyanka Sharma, Binay KumarDocumento8 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy: An Obstetric Review: Priyanka Sharma, Binay KumarkhairachungNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartal CardiomyopathyDocumento61 paginePeripartal CardiomyopathyAbnet WondimuNessuna valutazione finora

- Management of Women With Acquired Cardiovascular Disease From Pre-Conception Through Pregnancy and PostpartumDocumento14 pagineManagement of Women With Acquired Cardiovascular Disease From Pre-Conception Through Pregnancy and PostpartumJesús MorenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiomyopathy in Pregnancy: Jennifer Lewey, MD, and Jennifer Haythe, MDDocumento11 pagineCardiomyopathy in Pregnancy: Jennifer Lewey, MD, and Jennifer Haythe, MDAlika MaharaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Heart Failure in Pregnant Women: Is It Peripartum Cardiomyopathy?Documento6 pagineHeart Failure in Pregnant Women: Is It Peripartum Cardiomyopathy?NengLukmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy A ReviewDocumento9 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy A ReviewNur Rahmat WibowoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kardiomyopathien Und Kongenitale Vitia in Der SchwangerschaftDocumento6 pagineKardiomyopathien Und Kongenitale Vitia in Der SchwangerschaftDulanjalee KatulandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heart FailureDocumento4 pagineHeart FailureHany ElbarougyNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy CIRCULATIONAHADocumento13 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy CIRCULATIONAHAJessica WiryantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Circinterventions 120 008687Documento13 pagineCircinterventions 120 008687ronianandaperwira_haNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocumento15 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Literature Reviewfirda rosyidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine: Peripartum CardiomyopathyDocumento13 pagineContemporary Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine: Peripartum CardiomyopathyNailahRahmahNessuna valutazione finora

- Circulationaha 115 020491 PDFDocumento13 pagineCirculationaha 115 020491 PDFNailahRahmahNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Disease and Pregnancy Journal o NCM 102Documento15 pagineCardiovascular Disease and Pregnancy Journal o NCM 102MichelleIragAlmarioNessuna valutazione finora

- RHD and Maternal and Child Health ConnectionDocumento2 pagineRHD and Maternal and Child Health ConnectionChari RivoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kulkarni 2021Documento31 pagineKulkarni 2021kemoNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Myocardial Infarction During PregnancyDocumento10 pagineAcute Myocardial Infarction During PregnancyBinod KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy and Maternal Outcome - A Retrospective StudyDocumento7 pagineCardiac Disease in Pregnancy and Maternal Outcome - A Retrospective StudyIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 Esc PPCMDocumento17 pagine2019 Esc PPCMJayden WaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Coronary in PregnancyDocumento7 pagineAcute Coronary in PregnancygresiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 10.1258 Om.2008.080002Documento5 pagine10.1258 Om.2008.080002ade lydia br.siregarNessuna valutazione finora

- Zacharzewski 2019Documento6 pagineZacharzewski 2019Ario DaniantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Complicaciones CV en La EmbrazadaDocumento10 pagineComplicaciones CV en La EmbrazadaZaida RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardio-Obstetrics, Reconociendo Cardiopatias en Embarazo 2021Documento10 pagineCardio-Obstetrics, Reconociendo Cardiopatias en Embarazo 2021alejandro montesNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Emergenciesinpregnancy: Tala K. Al-Talib,, Stanley S. Liu,, Mukta SrivastavaDocumento11 pagineCardiovascular Emergenciesinpregnancy: Tala K. Al-Talib,, Stanley S. Liu,, Mukta SrivastavaAlika MaharaniNessuna valutazione finora

- ACS and STEMI Treatment: Gender-Related Issues: The Stent For Life InitiativeDocumento9 pagineACS and STEMI Treatment: Gender-Related Issues: The Stent For Life InitiativeChan ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rezai, 2016Documento9 pagineRezai, 2016Karina PuspaseruniNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidural Anesthesia For Cesarean Section For Pregnant Women With Rheumatic Heart Disease and Mitral StenosisDocumento6 pagineEpidural Anesthesia For Cesarean Section For Pregnant Women With Rheumatic Heart Disease and Mitral StenosisNengLukmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy An Unforeseen CatastropheDocumento3 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy An Unforeseen CatastropheBIOMEDSCIDIRECT PUBLICATIONSNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Early Onset Preeclampsia On Cardiovascular Risk in The Fifth Decade of Life - 2017 - American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology PDFDocumento7 pagineEffect of Early Onset Preeclampsia On Cardiovascular Risk in The Fifth Decade of Life - 2017 - American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology PDFfujimeisterNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Cardiology: ClinmedDocumento6 pagineClinical Cardiology: ClinmedArdisa MeilitaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Maternal and Neonatal Outcome in Pregnant Women With Cardiac DiseaseDocumento6 pagineA Study of Maternal and Neonatal Outcome in Pregnant Women With Cardiac DiseaseInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ni Hms 876731Documento16 pagineNi Hms 876731LannydchandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Hema Gayathri Arunachalam, Et AlDocumento8 pagineHema Gayathri Arunachalam, Et Aluswatun khasanahNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy ReviewDocumento14 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy ReviewWalter Saavedra Yarleque100% (1)

- European J of Heart Fail - 2021 - Sliwa - Risk Stratification and Management of Women With Cardiomyopathy Heart FailureDocumento14 pagineEuropean J of Heart Fail - 2021 - Sliwa - Risk Stratification and Management of Women With Cardiomyopathy Heart FailureRui FonteNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S2666668520300495 MainDocumento7 pagine1 s2.0 S2666668520300495 MainHadikagusti AdoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case ReportDocumento5 pagineAcute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case Reporteditorial.boardNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital HillsideDocumento11 pagineHospital HillsideJuan Carlos RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: Zolt Arany, and Uri ElkayamDocumento14 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy: Zolt Arany, and Uri ElkayamGheny Qurrota'ayuniNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pregnant Woman With Heart Disease: Management of Pregnancy and DeliveryDocumento5 pagineThe Pregnant Woman With Heart Disease: Management of Pregnancy and DeliveryMichael SusantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Abstrak Makalah Bebas MedanDocumento11 pagineAbstrak Makalah Bebas Medandr.raziNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: One Disease With Many FacesDocumento3 paginePeripartum Cardiomyopathy: One Disease With Many FacesVivi DeviyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- SJMPS 69 616-621 C x9IOCOHDocumento6 pagineSJMPS 69 616-621 C x9IOCOHRezky amalia basirNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Key Concepts in Pathogenesis, Disease Management, and Interesting CasesDa EverandCardiac Sarcoidosis: Key Concepts in Pathogenesis, Disease Management, and Interesting CasesNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Management of Heart DiseaseDa EverandGender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Management of Heart DiseaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Noise ThermometerDocumento1 paginaNoise ThermometerMedika WisataNessuna valutazione finora

- Shigella Dysenteriae Serotype 1 in West Africa: Intervention Strategy For AnDocumento2 pagineShigella Dysenteriae Serotype 1 in West Africa: Intervention Strategy For AnMedika WisataNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil of OcimumDocumento4 pagineChemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil of OcimumMedika WisataNessuna valutazione finora

- Phytochemicals in Nutrition and HealthDocumento221 paginePhytochemicals in Nutrition and HealthMedika Wisata100% (7)

- Ebook Download LinksDocumento13 pagineEbook Download LinksPA201467% (3)

- Tetralogy of Fallot: Anatomic Variants and Their Impact On Surgical ManagementDocumento9 pagineTetralogy of Fallot: Anatomic Variants and Their Impact On Surgical ManagementRoberto AmayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kr2med 2006engDocumento62 pagineKr2med 2006engHind YousifNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiological PrinciplesDocumento25 paginePhysiological PrinciplesAdelinaPredescuNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The Ideal Cholesterol Level by Joel Fuhrman MDDocumento4 pagineWhat Is The Ideal Cholesterol Level by Joel Fuhrman MDDrRod SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Igcse Biology: Topic 1: Characteristics of Living OrganismsDocumento63 pagineIgcse Biology: Topic 1: Characteristics of Living OrganismsIndia IB 2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- ACLS ECG Rhythm Strips Pretest Question Answers (Quiz) PDFDocumento11 pagineACLS ECG Rhythm Strips Pretest Question Answers (Quiz) PDF김민길100% (1)

- Bradicardy ManagementDocumento7 pagineBradicardy ManagementMarshall ThompsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamentals of Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz 9 (25 Questions) - NurseslabsDocumento26 pagineFundamentals of Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz 9 (25 Questions) - NurseslabsCHINGANGBAM ANJU CHANUNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Technologies History of Medtech in United StatesDocumento1 paginaMedical Technologies History of Medtech in United StatesAthaliah Del MonteNessuna valutazione finora

- Physical Assessment and RosDocumento5 paginePhysical Assessment and Rosanna jean oliquianoNessuna valutazione finora

- More Biology Questions: Circulatory System - Circulation in Animals, Question Paper - 04Documento2 pagineMore Biology Questions: Circulatory System - Circulation in Animals, Question Paper - 04Dhadrmender NishadNessuna valutazione finora

- Med Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocumento90 pagineMed Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Diseasefrankozed1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Ecgs Made Easy 4th Edition Barbara J AehlertDocumento25 pagineTest Bank For Ecgs Made Easy 4th Edition Barbara J Aehlertgrinting.creation4qlo100% (42)

- Chest TraumaDocumento86 pagineChest TraumagibreilNessuna valutazione finora

- Different Kinds of DiseasesDocumento3 pagineDifferent Kinds of DiseasesI AccessNessuna valutazione finora

- Nand Foundation Academy, Shegaon. 9834274427: Xii - A DivDocumento10 pagineNand Foundation Academy, Shegaon. 9834274427: Xii - A DivSanket PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Can't Miss ECG FindingsDocumento61 pagineCan't Miss ECG FindingsVikrantNessuna valutazione finora

- Premature Ventricular Contractions: Reassure or Refer?: ReviewDocumento7 paginePremature Ventricular Contractions: Reassure or Refer?: ReviewFahmi RaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Pentagram Magazine Number 4 2019 EnglishDocumento39 paginePentagram Magazine Number 4 2019 EnglishtsdigitaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Frog Dissection HomeworkDocumento4 pagineFrog Dissection Homeworkaibiaysif100% (1)

- Case StudyDocumento5 pagineCase StudyMary Mae Boncayao50% (4)

- Bpes Structure and SyllabusDocumento39 pagineBpes Structure and SyllabussxjkmatpozzqwnyzdjNessuna valutazione finora

- Circulatory System VCE BiologyDocumento6 pagineCirculatory System VCE BiologyCallum KennyNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Physiology Applied To Critical Care and AnesthesiDocumento12 pagineCardiovascular Physiology Applied To Critical Care and AnesthesiLuis CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- LP1ncm109 YboaDocumento21 pagineLP1ncm109 YboaMargarette GeresNessuna valutazione finora

- Head To Toe Assessment - InserviceDocumento10 pagineHead To Toe Assessment - InservicelovelivetaylorNessuna valutazione finora

- Pendekatan Pada Pasien Anak (anamnesis+PF)Documento25 paginePendekatan Pada Pasien Anak (anamnesis+PF)Sarah AgustinNessuna valutazione finora

- CVDDocumento25 pagineCVDSameer ValsangkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Form-8 - 8 - 2019 1 - 03 - 13-1PMDocumento5 pagineForm-8 - 8 - 2019 1 - 03 - 13-1PMfirstjugglerNessuna valutazione finora

- Wireless Heart Attack Detection SystemDocumento3 pagineWireless Heart Attack Detection SystemIJSTENessuna valutazione finora