Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Rorty Historiography Four Genres PDF

Caricato da

Marinca Andrei0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

16 visualizzazioni15 pagineTitolo originale

rorty_historiography_four_genres(2).pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

16 visualizzazioni15 pagineRorty Historiography Four Genres PDF

Caricato da

Marinca AndreiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 15

IDEAS IN CONTEXT

Edited by Richard Rorty, J.B. Schneewind and Quentin Skinner

‘The books in this series will discuss the emergence of intellectual traditions and of

‘elated new disciplines, The procedures, aims and vocabularies that were generated

will be ser in the context of the alternatives available within the contemporary

frameworks of ideas and institutions. Through detailed studies ofthe evolution of

such traditions, and their modification by different audiences, it ishoped that 2 new

picture will form of the development of ideas in their concrete contexts. By this

‘means, artificial distinctions between the history of philosophy, of the various

sciences, of society and politics, and of literature, may be seen to dissolve

‘This is the first volume in the series, Forthcoming titles include:

JG. A. Pocock, Virtue, Commerce and History

David Lieberman, The Province of Legislation Determined

Noe! Malcolm, Hobbes and Voluntarism

‘Quentin Skinner, Studies in Early Modern Intellectual History

Edmund Leites (ed), Conscience and Casuistry in Early Modem Europe

Lynn 8. Joy, Gassendi the Atomist: Advocate of History in an Age of Science

Mark Goldie, The Tory Ideology: Poitce and Ideas im Restoration England

‘This series is published withthe support ofthe Exxon Education Foundation,

PHILOSOPHY IN

HISTORY

Essays on

the historiography of philosophy

EDITED BY

RICHARD RORTY

J.B. SCHNEEWIND

QUENTIN SKINNER

CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY PRESS

@ 1984

a ALASDAIR MAGINTYRE

Maclnyre, Alasdair. 1977. ‘Epistemological crises, dramatic narrative and che

philosophy of science’, The Monit 6o(4): 453-72 3

‘Owen, G. EL. 1961. Tithenai ta Phtinomena' in 8. Mansion (ed). Arstote et les >

‘probiémes de methode. Proceedings of the second Symposium Aristorlieum.

Louvain

4

The historiography of philosophy

four genres

RICHARD RORTY

[Rational and historical reconstructions

yee (at | | Analytic philosophers who have attempted ‘rational reconstruct

the arguments of great dead philosophers have done so in the hope of

rho

B scan these philosophers as contemporaries, a colleagues wit

‘Geycaneachangesiews, Thay haveaqual faci

oar oni

| mightas well sua over the,

they picture as mere doxographers. rather than seekers a ‘phical

however, have led to charges of anachronism.

| ea eee

j uth. Such reconstructions,

hia

nalytic historians of philosophy are fr

‘ntdie ape of propstionycszeny bigdebedin thier

Fis urged that we should not force Aristotle or Kant co take:

jougnals, Tris urged that

in current debates within philosophy of language or metaethies, There

seems to be a dilemma: either we anachronistically impose enough of our

problems and vo sand voebelmy ot the dead to make them conversational,

parters, oF we confine our iat rity co making their falsehoods

lok Tess ally By lang th ihe gue te -benighted simes in

which they were written.

“Those alternatives, however, do not constitute a dilemma. We should do

both ofthese things, but do them separately. We should seat she bistary,of

hilosophy as we treat the history of science. Inthe latter field, we have no

jing that we know beuier chan our ancestors what they were

2

oe

talking about. We do not think it anachronistic to say that Aristotle had a

false model of the heavens, or that Galen did not understand how the

circulatory system worked. We take.the pardonable ignorance of great

dead scientists for granted..We should be equally willing zo Siy-that

Aristotle was w ° nng-such things as real

‘Reaices, or Leibniz that God does not exist, or Descartes that the mind is,

just the central nervous system sda i herpaive description We

Resitate tierely Because we have colleagues who are themselves ignorant of

such facts, and whom we courteously describe not as ‘ignorant’, but as

Fb fay) |

|| “Under lo Merk j

Pid ye ig dd

Li | | PCeli

?

0

50 RICHARD RORTY

‘holding different philosophical views’. Historians of science have no

colleagues who believe in crystalline spheres, or who doubt Harvey's

account of circulation, and they are thus free from such constraints

‘There is nothing wrong with self-consciously letting our own

philosophical views dictate terms in which to describe the dead. But there

ae reasons for also describing them in other terms, their own terms. It is

useful to recreate the intellectual scene in which the dead lived,

in particular, the real and fag ee atch

{Geir Contemporaries (or sear-contemporaties). There are purposes for

whichitis useful know how people talked who did norkios! as muck

‘know. tt is in i ng asa ite cnimgain eet

f sages The anthropologist Wane TO Know

haw AEE fl llow-primitives as well as how they react to

instruction from missionaries. For this purpose he tries to get inside their

heads, and to think in terms which he would never dream of employing at

home. Similarly, the historian of science, who can imagine what Aristotle

might have said in a dialogue in heaven with Aristarchus and Prolemy,

knows something interesting which remains unknown to the Whiggish

astrophysicist who sees only how Aristotle would have been crushed by

Galileo's arguments. There is knowledge ~ historical knowledge - to be

gained which one can only. get by bracketing one's owa-better knowledge

about, eg, the movements of the heavens or thc existence of God

‘The Pursuit OF auch historical knowledge must obcy 2 constraint

formulated by Quentin Skinner:

VA

‘No agent can eventually be said to have mea

_never be brought to accept asa corect dese

‘Skinner 19692

Skinner says that this maxim excludes ‘the possibilty that an acceptable

account of an agent’s behaviour could ever survive the demonstration that

twas itself dependent on the use of criteria of description and classification

not available to che agent himsel?. There is an important sense of ‘what the

agent meant or did’, as of ‘account ofthe agent's behaviour’, for which this

isan ineluctable constraint. If we want an account of Aristotle's or Locke's

behaviour which obeys this constraint, however, we shall have to confine

‘ourselves to one which, atits ideal limit tells us what they might have said

in response to all the criticisms or questions which would have been aimed

at them by their contemporaries (or, more precisely, by that selection of

their contemporaries or near-contemporarics whose criticisms and ques-

tions they could have understood right off the bat — all the people who,

roughly speaking, ‘spoke the same language’, not least because they were

just as ignorant of what we now know as the great dead philosopher him-

or done something which he ma)

fon of what heat ment or done

The historiography of philosophy: four genres ”

self), We may want to go on to ask questions like “What would Aristotle

have said about the moons of Jupiter (or about Quine’s ant-essentialism)?”

‘or What would Locke have said about labour unions (or about Rawls)?’ or

sWhat would Berkeley have said about Ayer’s or Bennett’s attempt to

“inguistify” his views on sense-perception and matter But we shall not

describe the answers we envisage them giving to such questions as

descriptions of what they ‘meant or did’, in Skinner's sense ofthese terms.

The main reason se want historical knowledge.of what unce-educated

_ primitives, or dead philosophers and scientists.-would have said to each

__other is thas ithelps us in secagnize that thers havebeen different forms-af

_ imellectual lifethan-urs. As Skinner (1969:52-3) rightly says, ‘the

| indispensable value of studying the history of ideas’ is to learn “the

| distinction beeween what necessity

_ ar own contingent arrangements’. The latter is indeed, as he goes on to

“say, ‘the key co self-awareness itself’. But_we also want to imagine

conversations between ourselves (whose contingent itSinclude

_ general agreement that, e.g., there are no real essences, no God, etc.) and.

_ the mighty dead. We want this not simply because itis nise-1o feel one-up

‘on one’s betters, but because we would like to be able to. see the historyof

‘our race a8 a long conversational interchange, We want to be able to sex it

«Bat Wayin onder to assure ourselves that therehas been al progressin

the course of recorded history —that_we

| grounds which our ancestors couk

reassurance on this pointis as great as the need for self-awareness. Weneed

“0 imagine Aristotle studying Galileo or Quine and changing his mind,

Aquinas reading Newton or Hume and changing his, etc. We need to think.

| chat, in philosophy as in science, the mighty mistaken dead look down

from heaven at our recent successes, and are happy to find that their

_ mistakes have been corrected,

This means that we are interested not only in what the Aristotle who,

|" walked the streets of Athens ‘could be’ brought to accept as a correct

-description of what he had meant or done’ butin what an ideally reasonable

~ and educable Aristotle could be brought to accept as such a description, “}

|The ideal aborigine can eventually be brought to accept a description ol

“himself as having cooperated in the continuation of a kinship system

designed to facilitate the unjust economic arrangements of his tribe. An

ideal Gulag guard can eventually be brought to regard himself as having

betrayed his loyalty to his fellow-Russians. An ideal Aristotle can be

‘brought to describe himself as having mistaken the preparatory taxonomic

stages of biological research for the essence of all scientific inquiry. Each of

these imaginary people, by the time he has been brought to accept such a

new description of what he meant or did, has become ‘one of us’. Heis our

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 978-1-4438-3364-6 Proceedings Gyula Klima HallDocumento30 pagine978-1-4438-3364-6 Proceedings Gyula Klima HallMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Magadalena Bieniak The Soul-Body Problem at Paris, CA. 1200-1250. Hugh of St-Cher and His ContemporariesDocumento265 pagineMagadalena Bieniak The Soul-Body Problem at Paris, CA. 1200-1250. Hugh of St-Cher and His ContemporariesMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Anselm's Elusive ArgumentDocumento22 pagineAnselm's Elusive ArgumentMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus PL 706 S10Documento4 pagineSyllabus PL 706 S10Marinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cassarella, Cusanus and AnselmDocumento22 pagineCassarella, Cusanus and AnselmMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hopkins, How Not To Defend Anselm PDFDocumento9 pagineHopkins, How Not To Defend Anselm PDFMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Amy Laura Hall Kierkegaard and The Treachery of Love Cambridge Studies in Religion and Critical Thought 2002Documento236 pagineAmy Laura Hall Kierkegaard and The Treachery of Love Cambridge Studies in Religion and Critical Thought 2002Kostas FounNessuna valutazione finora

- Questiones Disputatae in IV Libros SenteDocumento577 pagineQuestiones Disputatae in IV Libros SenteMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Plato Timaeus As Cultural IconDocumento3 paginePlato Timaeus As Cultural IconMarinca Andrei50% (2)

- Spark Charts Latin GrammarDocumento6 pagineSpark Charts Latin GrammarMax Erdemandi100% (1)

- Paul Slomkowski Aristotle's TopicsDocumento232 paginePaul Slomkowski Aristotle's TopicsRomina De Angelis100% (7)

- The Restoration ofDocumento3 pagineThe Restoration ofMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

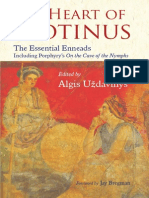

- The Heart of Plotinus:the Essential EnneadsDocumento294 pagineThe Heart of Plotinus:the Essential Enneadsincoldhellinthicket100% (23)

- Tim Mehigan The Critical Response To Robert Musils The Man Without Qualities Literary Criticism in Perspective 2003Documento196 pagineTim Mehigan The Critical Response To Robert Musils The Man Without Qualities Literary Criticism in Perspective 2003Marinca Andrei100% (1)

- The UnfinishedDocumento8 pagineThe UnfinishedMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hovering LifeDocumento18 pagineThe Hovering LifeMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Didascalicon of Hugh of St. VictorDocumento278 pagineDidascalicon of Hugh of St. VictorkexteNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient Greek Literature: From Homer to the Byzantine EmpireDocumento2 pagineAncient Greek Literature: From Homer to the Byzantine EmpireTiffany Paño MateoNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Subject of MetaphysicsDocumento49 pagineOn The Subject of MetaphysicsMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocumento6 pagineNew Microsoft Word DocumentMarinca AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Didascalicon of Hugh of St. VictorDocumento278 pagineDidascalicon of Hugh of St. VictorkexteNessuna valutazione finora

- Spark Charts Latin GrammarDocumento6 pagineSpark Charts Latin GrammarMax Erdemandi100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)