Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

HIS Andropov

Caricato da

Slate magazineTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

HIS Andropov

Caricato da

Slate magazineCopyright:

Formati disponibili

C05157765 3.

5(c)

Approved for Release: 2015/09/25 C05157765

Yuriy Viadimirovich ANDROPOV USSR

(Phonetic: ahnDRAWpuf)

General Secretary and lblember,

Politburo, Central Committee,

Communist Party of the Soviet

Union

Addressed as:

Mr. Secretary

Yuriy Andropov succeeded Leonid Brezhnev

as General Secretary of the CPSU on 12 November

1982, the day after Brezhnev's death was

announced. A member of the ruling Politburo since

1973, Andropov is one of only three people who

have dual status as full members and Central

Committee secretaries. When he took his new job,

he indicated that collective leadership would

continue to be the rule in the Soviet Union. At

present, however, he appears to be clearly in charge, even though the extent of his power has

not yet been defined. As the Soviet leader, Andropov faces formidable domestic challenges,

including an entrenched and aging bureaucratic structure, a Communist Party riddled with

cynicism and corruption, and an economy whose performance is in serious decline. We

believe that he bas the. resourcefulness, astuteness, and political skills needed to take on

these problems. 3.5(c)

Andropov is perhaps the most complicated and puzzling of all the current Soviet

l:;hders. A sophisticated man, he is probably better informed on foreign affairs, and on at

least some domestic matters, than any other Soviet party chief since Lenin. Throughout his

entire career, Andropov has shown a single-minded devotion to the Communist cause. He

appears to have a capacity for ruthlessness, but it is possible that what seems ruthless to a

non-Soviet observer is, to Andropov, merely an action to support or further the cause of

Communism and the supremacy of the Soviet state. 3.5(c)

Andropov does not fit the stereotype of the dull, gray bureaucrat. He is reserved and

unassuming; his quiet approach is unusual among Soviet leaders. Serious minded and

pragmatic, he exudes self-confidence. He is suave and gentlemanly--even when dealing with

his victims. He listens to new ideas, gathers information carefully, relies on exhaustive staff

work, evaluates consequences and possible actions cautiously, and acts resolutely. His

approach is to try to win through stratagem and maneuver but to resort to force when all

else fails and he deems the risks acceptable, 3.5(c)

Among his closest personal and professional friends, Andropov counts Defense Minister

Dmitriy Ustinov, Foreign Minister Andrey Gromyko, and, paradoxically, former CPSU

Secretary Andrey Kirilenko- -one of those he edged out in the competition for leadership.

He appears to have been close to the late party ideologue Mikhail Suslov, the patron of

Soviet conservatives, whose views are still shared by many in the leadership. Andropov was

close to Brezhnev professionally for years, and the late General Secretary clearly regarded

him as an astute adviser 3.5(c)

At the same time, one of the most striking features of Andropov's background is his

independence. He is apolitical loner. Unlike many of his colleagues, he did not fawn upon

Brezhnev but treated him in a straightforward manner. Andropov is not regarded as the protege

of any senior Soviet leader past or present. By the same token, unusual for the Soviet system,

only a few men can be characterized as his own proteges. Even though he has long functioned

within a framework of collective decisionmaking, he is, by all accounts, his own man 3.5(c)

(cont.) 3.5(c)

CR M 83-10298

Approved for Release: 2015/09/25 C05157765

COS 1 S 7 7 6 S 3.5(c)

Approved for Release: 2015/09/25 C05157765

Views on Major Issues.

Andropov's views on major issues are known primarily from his public statements. He

has emphasized the need for a strong Soviet defense capability, but he has also said that

military strength alone will not maintain peace. He has warned that a nuclear war would

have catastrophic consequences and has spoken out in favor of East-West detente, arms

control, and the reduction of international tensions. Like other Soviet leaders, Andropov has

blamed Washington for the deterioration of East-West relations since the late 1970s while

professing optimism about the long-range prospects for detente. His remarks have been

distinguished by a sensitvity to the diversity of opinion among Western leaders 3.5(c)

When Andropov was chairman of the KGB during 1967-82, he spoke at greater length

than most Soviet leaders about external and internal threats to the Soviet system. He

maintained that human rights pledges signed by Moscow at the 1975 Helsinki Conference

on Security and Cooperation in Europe did not restrict Soviet actions against dissidents. He

has stressed the need for constant vigilance against the threat of Western-inspired

subversion. Andropov has consistently maintained that Moscow has a duty to assist

"national liberation" struggles in the Third World, particularly when they are opposed by

Western nations. His commen r the years have followed the dominant

leadership line of the moment. 3.5(c)

Career and Personal Data

During his career Andropov has alternated between party and government posts. After

holding positions in the Komsomol (Young Communists League) and party in the Karelo-

Finnish republic, he worked in the central party apparatus in Moscow before being

appointed Ambassador to Hungary in 1954. In that capacity, he was an intermediary

between the Soviet and Hungarian Governments at the time of the 1956 Hungarian revolt.

During 1957-67 he was in charge of party relations with Bloc Communist parties in the

CPSU Secretariat, and he was a party secretary from 1962 until 1967. Andropov spent the

next 15 years in the government as chairman of the KGB. t in May 1982,

when he was again elected a Central Committee secretary 3.5(c)

Despite press reports that the KGB became less repressive under Andropov's

chairmanship, the trend away from mass terror and toward lawful procedures had actually

begun earlier. Compared to the operations of the secret police during the Stalin years, KGB

operations under Andropov appeared restrained, tolerant, and restricted by the letter of

Soviet law--even though by Western standards, those operations were seen as repressive,

coercive, and sometimes brutal 3.5(c)

It is in the crippling of the Soviet dissident movement that Andropov's sophistication

and cleverness seem most apparent. Through a mixture of tactics from leniency to brutality,

the KGB largely eradicated the "dissident" movement in. the USSR, doing so without

derailing the Soviet policy of detente. There were some arrests, trials, and harsh sentences;

but there were also cases in which mild sentences were imposed or the subject of the

proceeding was allowed to emigrate or was expelled. Dissent seems to have been handled on

a case-by-case basis, with the emphasis on defusing each problem as it arose 3.5(c)

Andropov is an art collector and enjoys music and literature. He speaks English and

Hungarian. He had a heart attack several years ago but appears to be in fairly good health

at present. A recent press report states that Andropov, 68, is a widower. He has a grown son

and daughter.F---] 3.5(c)

2 11 January 1983

3.5(c)

Approved for Release: 2015/09/25 C05157765

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Ned Kelly Films: A Cultural History of Kelly HistoryDa EverandThe Ned Kelly Films: A Cultural History of Kelly HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Able Archer 83 What Were The Soviets ThinkingDocumento25 pagineAble Archer 83 What Were The Soviets ThinkingcazarottoNessuna valutazione finora

- Days With Lenin: by Maxim GorkyDocumento43 pagineDays With Lenin: by Maxim GorkySgt. WurstfingerNessuna valutazione finora

- Lenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, Vol. 17Documento640 pagineLenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, Vol. 17abcd_9876100% (1)

- Dudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card (2006)Documento300 pagineDudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card (2006)raj patel100% (1)

- Lenin Newspaper PDFDocumento8 pagineLenin Newspaper PDFEmiliano Aguila MonteblancoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, Vol. 30Documento604 pagineLenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, Vol. 30abcd_9876100% (1)

- Politics Work and Daily Life in The Ussr. A Survey of Former Soviet CitizensDocumento625 paginePolitics Work and Daily Life in The Ussr. A Survey of Former Soviet Citizenscaiofelix_rjNessuna valutazione finora

- Russian Jewish LitDocumento8 pagineRussian Jewish LitKeith KoppelmanNessuna valutazione finora

- INGLES - Montesquieu, My Thoughts (2012) PDFDocumento786 pagineINGLES - Montesquieu, My Thoughts (2012) PDFEduardo SandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Ragsdale Tsar PaulDocumento279 pagineRagsdale Tsar PaulNenad Cveticanin100% (1)

- Pictures of Poverty: The Works of George R. Sims and Their Screen AdaptationsDa EverandPictures of Poverty: The Works of George R. Sims and Their Screen AdaptationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ivan Colovic (2019) The Myth of KosovoDocumento17 pagineIvan Colovic (2019) The Myth of KosovoLefteris Makedonas100% (1)

- (Instrumentality of Mankind) No, No, Not Rogov - Cordwainer SmithDocumento11 pagine(Instrumentality of Mankind) No, No, Not Rogov - Cordwainer SmithJustinSnowNessuna valutazione finora

- Sergei Malyshev, Unemployed Councils in St. Petersburg in 1906. New York, Workers Library, 1931.Documento50 pagineSergei Malyshev, Unemployed Councils in St. Petersburg in 1906. New York, Workers Library, 1931.danielgaidNessuna valutazione finora

- Kropotkin - Ideals and Realities in Russian LiteratureDocumento358 pagineKropotkin - Ideals and Realities in Russian LiteratureDale R. Gowin100% (1)

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 pagineAnnotated BibliographyHistory FairNessuna valutazione finora

- Anton DrexlerDocumento2 pagineAnton DrexlerValpo Valparaiso100% (2)

- R. V Ekaireb (Robert David)Documento17 pagineR. V Ekaireb (Robert David)michale smithNessuna valutazione finora

- Banners of The Insurgent Army of N. Makhno 1918-1921Documento10 pagineBanners of The Insurgent Army of N. Makhno 1918-1921Malcolm ArchibaldNessuna valutazione finora

- Nugget For Pavelic - Bosco Spills The BeansDocumento5 pagineNugget For Pavelic - Bosco Spills The BeansPatrick FourmyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Collapce of Lenins Cult in The UssrDocumento19 pagineThe Collapce of Lenins Cult in The UssrSilina Maria100% (1)

- Lenin Complete Works 44 PDFDocumento624 pagineLenin Complete Works 44 PDFPazuzu8100% (1)

- Gluckstein (1983) - The Missing Party PDFDocumento43 pagineGluckstein (1983) - The Missing Party PDFMajor GreysNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Serafimovich. The Iron Flood. 1935Documento127 pagineA. Serafimovich. The Iron Flood. 1935Grover FurrNessuna valutazione finora

- China As A Factor in The Collapse of The Soviet EmpireDocumento19 pagineChina As A Factor in The Collapse of The Soviet EmpireAndreea BădilăNessuna valutazione finora

- Avedon R Avedon Photographs 19471977Documento220 pagineAvedon R Avedon Photographs 19471977Эраст ФандоринNessuna valutazione finora

- New Beijing, Great Olympics - Beijing and Its Unfolding Olympic LegacDocumento15 pagineNew Beijing, Great Olympics - Beijing and Its Unfolding Olympic LegacJessye FreymondNessuna valutazione finora

- For A Lasting Peace, For A People's Democracy! No. 1Documento128 pagineFor A Lasting Peace, For A People's Democracy! No. 1stainedClassNessuna valutazione finora

- Israel Getzler Kronstadt 1917-1921 The Fate of A Soviet Democracy Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies 1983Documento308 pagineIsrael Getzler Kronstadt 1917-1921 The Fate of A Soviet Democracy Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies 1983Pablo PoleseNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hidden GulagDocumento122 pagineThe Hidden Gulaggruiabarbu100% (1)

- John MiliusDocumento11 pagineJohn MiliusMIDNITECAMPZNessuna valutazione finora

- Feel PirosmaniDocumento1 paginaFeel PirosmaniGeorgian National MuseumNessuna valutazione finora

- Killer Math 1Documento18 pagineKiller Math 1Swapnil Dhasmana100% (1)

- Rubber Soul Listening GuideDocumento2 pagineRubber Soul Listening GuideBrian ClemensNessuna valutazione finora

- Maxim Gorky His Life and WritingsDocumento561 pagineMaxim Gorky His Life and Writingsjobox1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Joseph Mitchell William Walker - The Missionary Pioneer, or A Brief Memoir of The Life, Labours, and Death of John Stewart, (Man of Colour) (1918)Documento104 pagineJoseph Mitchell William Walker - The Missionary Pioneer, or A Brief Memoir of The Life, Labours, and Death of John Stewart, (Man of Colour) (1918)chyoungNessuna valutazione finora

- Harvard - Adolf EichmannDocumento13 pagineHarvard - Adolf EichmannJD MayweatherNessuna valutazione finora

- Guttmann FotoperiodismoDocumento14 pagineGuttmann FotoperiodismoJabi EsparzaNessuna valutazione finora

- BasicsOfMarxist LeninistTheoryDocumento50 pagineBasicsOfMarxist LeninistTheoryckwaigNessuna valutazione finora

- Four Hours in Shatila - Jean GenetDocumento21 pagineFour Hours in Shatila - Jean GenetIman GanjiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hermann Neubacher and Austrian Anschluss Movement 1918-40 PDFDocumento24 pagineHermann Neubacher and Austrian Anschluss Movement 1918-40 PDFtandor91Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dostoevsky - A Revolutionary ConservativeDocumento7 pagineDostoevsky - A Revolutionary ConservativeMalgrin2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kolarz-Russia Colonies PDFDocumento102 pagineKolarz-Russia Colonies PDFHarald_LarssonNessuna valutazione finora

- Hamsun, Knut - On Over-Grown Paths (Eriksson, 1967)Documento187 pagineHamsun, Knut - On Over-Grown Paths (Eriksson, 1967)cassirer12100% (1)

- Kabab e GhazDocumento7 pagineKabab e Ghaz2ndmoonNessuna valutazione finora

- Joseph Stalin PresentationDocumento17 pagineJoseph Stalin PresentationJosef FusekNessuna valutazione finora

- A. J. Weberman On William BlakeDocumento4 pagineA. J. Weberman On William BlakeAlan Jules WebermanNessuna valutazione finora

- Anna M. Cienciala. Poles and Jews Under German and Soviet Occupation, September 1, 1939 - June 22 1941Documento13 pagineAnna M. Cienciala. Poles and Jews Under German and Soviet Occupation, September 1, 1939 - June 22 1941Slavchyk2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spartacist League Lenin and The Vanguard Party 1978 James Robertson in Defence of Democratic Centralism 1973Documento85 pagineSpartacist League Lenin and The Vanguard Party 1978 James Robertson in Defence of Democratic Centralism 1973Sri NursyifaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pionner Organization. The Evolution of Citizenship Education in The Soviet UnionDocumento252 pagineThe Pionner Organization. The Evolution of Citizenship Education in The Soviet Union15206649Nessuna valutazione finora

- Anthony Burgess - Finnegans Wake. What It' S All AboutDocumento24 pagineAnthony Burgess - Finnegans Wake. What It' S All AboutPablo Ernesto Lachener100% (1)

- Transcripts From The Soviet Archives Volume 3Documento643 pagineTranscripts From The Soviet Archives Volume 3Titan RojoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lorenzen - Who Invented HinduismDocumento31 pagineLorenzen - Who Invented Hinduismvlad-b100% (1)

- Vernon Bogdanor - September 2010Documento11 pagineVernon Bogdanor - September 2010AlejandraNessuna valutazione finora

- KRUPSKAYA, N. (Livro, Inglês, 1933) Reminiscences of Lenin PDFDocumento292 pagineKRUPSKAYA, N. (Livro, Inglês, 1933) Reminiscences of Lenin PDFAll KNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022-08029 - Final Order (GQ)Documento5 pagine2022-08029 - Final Order (GQ)Slate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Life or DeathDocumento3 pagineLife or DeathSlate magazine100% (1)

- Pltfs Brief in Opp To Defs MSJ REDACTEDDocumento41 paginePltfs Brief in Opp To Defs MSJ REDACTEDSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Open Letter - R. KellyDocumento2 pagineOpen Letter - R. KellySlate magazine100% (1)

- Virginia: in The Circuit Court For The City of Virginia Beach in Re: A Court of Mist and Fury Case No. CL22-1984 Final OrderDocumento4 pagineVirginia: in The Circuit Court For The City of Virginia Beach in Re: A Court of Mist and Fury Case No. CL22-1984 Final OrderSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Volunteer Nurse LetterDocumento7 pagineVolunteer Nurse Letterapi-300774614Nessuna valutazione finora

- R. Kelly ReleaseDocumento2 pagineR. Kelly ReleaseSlate magazine100% (1)

- Read Trump's Letter To PelosiDocumento6 pagineRead Trump's Letter To Pelosikballuck194% (95)

- LAS Ltr. To Cuomo and DOCCS Re COVID 19 Vulnerable IndividualsDocumento27 pagineLAS Ltr. To Cuomo and DOCCS Re COVID 19 Vulnerable IndividualsSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- In Search of A New Home: Reflections On R. Kelly, Sexual Violence, and SilenceDocumento16 pagineIn Search of A New Home: Reflections On R. Kelly, Sexual Violence, and SilenceSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Report For Delhi Police: Dealing With Second WaveDocumento11 pagineReport For Delhi Police: Dealing With Second WaveSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Vera-O'Keefe Settlement AgreementDocumento8 pagineVera-O'Keefe Settlement AgreementSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Final 2018 New Members of CongressDocumento9 pagineFinal 2018 New Members of CongressSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Jim Spanfeller Is A HerbDocumento6 pagineJim Spanfeller Is A HerbSlate magazine100% (4)

- Doorbell Sign 5Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 5Slate magazine0% (1)

- Doorbell Sign 6Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 6Slate magazine100% (1)

- Doorbell Sign 4Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 4Slate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Doorbell Sign 1Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 1Slate magazine0% (2)

- Doorbell Sign 3Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 3Slate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Doorbell Sign 2Documento1 paginaDoorbell Sign 2Slate magazine0% (1)

- Ukraine Call Talking PointsDocumento1 paginaUkraine Call Talking PointsSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Beaver Emoji ProposalDocumento11 pagineBeaver Emoji ProposalSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- AG March 24 2019 Letter To House and Senate Judiciary CommitteesDocumento4 pagineAG March 24 2019 Letter To House and Senate Judiciary Committeesblc8893% (70)

- Koko ComplaintDocumento24 pagineKoko ComplaintSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Outward: 15th Anniversary of The L-WordDocumento1 paginaOutward: 15th Anniversary of The L-WordNatalie Matthews-RamoNessuna valutazione finora

- First Day Briefing - Nadja WestDocumento34 pagineFirst Day Briefing - Nadja WestSlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Army Medicine Campaign Plan 2018Documento24 pagineArmy Medicine Campaign Plan 2018Slate magazine100% (1)

- Exhibit ADocumento5 pagineExhibit ASlate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Thinking of You (P&T)Documento1 paginaThinking of You (P&T)Slate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- Rogue Male (P&T)Documento1 paginaRogue Male (P&T)Slate magazineNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ADocumento7 pagine10 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ANico FalzoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Cartographie Startups Françaises - RHDocumento2 pagineCartographie Startups Françaises - RHSandraNessuna valutazione finora

- X3 45Documento20 pagineX3 45Philippine Bus Enthusiasts Society100% (1)

- Iraq-A New Dawn: Mena Oil Research - July 2021Documento29 pagineIraq-A New Dawn: Mena Oil Research - July 2021Beatriz RosenburgNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Report On Salford Estates (No. 2) Limited V AltoMart LimitedDocumento2 pagineCase Report On Salford Estates (No. 2) Limited V AltoMart LimitedIqbal MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- RA-070602 - REGISTERED MASTER ELECTRICIAN - Manila - 9-2021Documento201 pagineRA-070602 - REGISTERED MASTER ELECTRICIAN - Manila - 9-2021jillyyumNessuna valutazione finora

- Gogo ProjectDocumento39 pagineGogo ProjectLoyd J RexxNessuna valutazione finora

- PoetryDocumento5 paginePoetryKhalika JaspiNessuna valutazione finora

- Busi Environment MCQDocumento15 pagineBusi Environment MCQAnonymous WtjVcZCg57% (7)

- Gouri MohammadDocumento3 pagineGouri MohammadMizana KabeerNessuna valutazione finora

- Implementation of Brigada EskwelaDocumento9 pagineImplementation of Brigada EskwelaJerel John Calanao90% (10)

- Special Penal LawsDocumento14 pagineSpecial Penal LawsBrenna ColinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Retail Strategy: MarketingDocumento14 pagineRetail Strategy: MarketingANVESHI SHARMANessuna valutazione finora

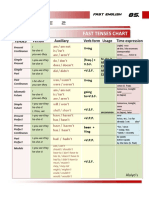

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDocumento5 pagineTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Study in USADocumento4 pagineWhy Study in USALowlyLutfurNessuna valutazione finora

- Grameenphone Integrates Key Technology: Group 1 Software Enhances Flexible Invoice Generation SystemDocumento2 pagineGrameenphone Integrates Key Technology: Group 1 Software Enhances Flexible Invoice Generation SystemRashedul Islam RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- BB 100 - Design For Fire Safety in SchoolsDocumento160 pagineBB 100 - Design For Fire Safety in SchoolsmyscriblkNessuna valutazione finora

- RBI ResearchDocumento8 pagineRBI ResearchShubhani MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- CTC VoucherDocumento56 pagineCTC VoucherJames Hydoe ElanNessuna valutazione finora

- Barrier Solution: SituationDocumento2 pagineBarrier Solution: SituationIrish DionisioNessuna valutazione finora

- S0260210512000459a - CamilieriDocumento22 pagineS0260210512000459a - CamilieriDanielNessuna valutazione finora

- A Wolf by The Ears - Mattie LennonDocumento19 pagineA Wolf by The Ears - Mattie LennonMirNessuna valutazione finora

- Marking SchemeDocumento8 pagineMarking Schememohamed sajithNessuna valutazione finora

- Usaid/Oas Caribbean Disaster Mitigation Project: Planning To Mitigate The Impacts of Natural Hazards in The CaribbeanDocumento40 pagineUsaid/Oas Caribbean Disaster Mitigation Project: Planning To Mitigate The Impacts of Natural Hazards in The CaribbeanKevin Nyasongo NamandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem Solving and Decision MakingDocumento14 pagineProblem Solving and Decision Makingabhiscribd5103Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sales-Management Solved MCQsDocumento69 pagineSales-Management Solved MCQskrishna100% (3)

- Minutes of Second English Language Panel Meeting 2023Documento3 pagineMinutes of Second English Language Panel Meeting 2023Irwandi Bin Othman100% (1)

- Slavfile: in This IssueDocumento34 pagineSlavfile: in This IssueNora FavorovNessuna valutazione finora

- International Law Detailed Notes For Css 2018Documento95 pagineInternational Law Detailed Notes For Css 2018Tooba Hassan Zaidi100% (1)

- Satisfaction On Localized Services: A Basis of The Citizen-Driven Priority Action PlanDocumento9 pagineSatisfaction On Localized Services: A Basis of The Citizen-Driven Priority Action PlanMary Rose Bragais OgayonNessuna valutazione finora