Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Otto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To Ockham

Caricato da

mehmetmsahinTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Otto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To Ockham

Caricato da

mehmetmsahinCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Tradition of the Logical Topics: Aristotle to Ockham

Author(s): Otto Bird

Source: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1962), pp. 307-323

Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2708069 .

Accessed: 21/06/2014 10:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of the History of Ideas.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE TRADITION OF THE LOGICAL TOPICS:

ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM

BY OTTo BIRD

FromthetimeofAristotle untillatein theRenaissancetheTopics

occupiedan important placein thestudyoflogicandlanguage.There

are also signsthatsomething likea re-discoveryof themis occurring

in contemporary philosophicaldiscussion(cf.BIR).* Yet littleeffort

has beenmadeto analysetheirdevelopment. In thispaperI propose

to studythatdevelopment in the formit reachedin late mediaeval

logicthrough theworkofAristotle, Boethius, PeterofSpain,andOck-

a I

ham.Thisis still verylargesubject,and shallaccordingly restrict

myattention primarilyto twoaspects:(1) howAristotle's wide-rang-

ingconsideration of theTopicswas systematized in Boethiusand in

thatformtransmitted, especiallyby PeterofSpain,to thelate medi-

aeval logicians;(2) howformallogicalelementswereisolatedin the

Topicsand analysedfortheirownsake.Sincethelanguageofmodern

logicis ideallysuitedformanifesting logicalform,I shallavailmyself

ofit to showtheformalcontentoftheTopicaltradition.

The Topicsin Aristotle

The largestsingleworkamongAristotle's logicalwritings is the

one thatis devotedto theTopics.Its size is certainly due in partto

thediversity ofmaterialthatit contains, enoughin factto inspireat

leastthreedistincttreatisesin laterlogic:De praedicabilibus on the

predicables,De obligationibus dealingwiththelogicofformaldispu-

tation,De locison theTopics.In additionto theseit containsa theory

of probablereasoningand thusis the source,primarily in its intro-

ductorybook,forthe Aristotelian theoryof dialectic.Withinthe

Aristoteliantraditionit is customary to distinguish

fourdifferent con-

siderationsofthesyllogism: thatdevotedto theformalstudyof the

syllogism in the PriorAnalytics, the analysisof the necessaryand

demonstrative syllogism in the PosteriorAnalytics, of the probable

and dialecticalsyllogism in the Topics,and of the apparentbut fal-

lacioussyllogism in theSophisticalRefutations.

The topoi,whichgive theirname to the workas a whole,are

treatedin BooksII-VII, thefinalbookbeingturnedovermostlyto a

methodology ofdiscussion. The Topics,theobjectofourconcern, are

organizedaccordingto what laterare called the predicables.Thus

Books II-III treatthe Topics concernedwithAccident,Book IV

Genus,BookV Property, and BooksVI-VII Definition.

Perhapsthe shortest way of seeingwhatAristotle does withthe

Topicsis to lookat a typicaltext.ForthatpurposeI havechosenBk.

* Suchcitations

are to theworkslistedin theTable of References

at theendof

thisarticle.

307

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

308 OTro BIRD

II ch. 4, 111a14-33.On a literalreadingit runsas follows(withmy

numbering oftheindividualsentences):

(1) To showthatcontrary accidentsbelong inthesamesubjectlookto

thegenus.(2) Forexample, toshowthatright andwrong applyto percep-

tionweargue:To perceive is to judge;butwejudgerightly andwrongly;

so weperceive rightly andwrongly. (3) Thisproofis from thegenusand

concerns species,sincejudging is thegenusofperceiving, foronewhoper-

ceivesjudgesinsomeway.(4) It is alsopossible toproceed from speciesto

genus, sincewhatever is inthespeciesis alsointhegenus.(5) Forexample,

ifthere is goodandbadknowledge, there is alsoa goodandbaddisposition,

sincedispositionis thegenusofknowledge.

(6) Thefirst topicis falseforconfirming, whilethesecond is true.

(7) Forit is notnecessary thatwhatever is in thegenusis alsoin the

species.Animal is flyingandquadruped, whilemanis not.

(8) Butwhatever is in thespeciesis necessarily in thegenus;thusif

manis good,thenanimalalsois good.

(9) Thefirst topicis trueforrefuting, forwhatever is notinthegenus

is notinthespecies.

(10) Thesecondtopicis falseforrefuting, forit is notnecessary that

whatis notinthespeciesis notinthegenus.

In (1) Aristotle statesthe problem, whichin thiscase concerns

accident.He immediately providesin (2) an exampleofan argument

in concreteterms.Aboutthishe notes(3) thatwe are arguingfrom

a genusto something abouta species,sincethetermsoftheexample

are related genus species.He thenobserves(4) thatwe can re-

as to

versethe orderand arguefromspeciesto genus,and forthislatter

way of arguinghe citesthe warrantor rulethatwhateveris in the

speciesis also in thegenus.For thishe givesanotherexamplein con-

creteterms(5).

Up to thispointAristotle has giventwomodesof arguingwith

examples:fromgenusto speciesand thereverse.He nowproceedsto

evaluatetheirlogicalforceaccording to theiruse in "confirming"

or

"refuting," i.e. he considersbothaffirmative and negativeformsof

thesetwomodes.Thuswe geta totaloffourformsto consider. Aris-

totle then observeswhethereach formis "necessary"or not, i.e.

whether it is logicallynecessary and therefore alwaystrueor not.In

otherwords, he is in effect

determining whether ornotwehavea logi-

cal law. It is accordingly helpfulif we put his arguments in modern

logicalnotation.'

In translating Aristotle'sexpressions intologicalnotation,

thereis

oftenan embarrassment of riches,sincethereare manyequivalent

formsforeach. In general,however, it wouldseembestto approxi-

matetheformoftheoriginalas closelyas possible.

Forthislogicaltranslation

hereandin whatfollows

I havebeenfortunate

to

havethehelpand adviceofDr. C. LejewskiofManchester

University,

Visiting

Pro-

fessor ofNotreDame 19061, whohaskindly

at theIUniversity readmymanuscript.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 309

Aristotlein the above text speaksof something "beingin the

genus"and givestheexampleofquadrupedandanimal(7). Withthis

as thestandard,I take 'quadrupedis in animal'or,in general,'F is

in B' thus:

(rx).xeB.Fx. .F is inB

Withthisinterpretation

Aristotle's

arguments maybe formalized

as

follows:

*A1.1 A?B.o: (F): (Vx).xeB.Fx.o. (,[x).xEA.Fx

It is notnecessary thatwhatever is in thegenusis alsoin thespecies.

'If an animalis quadruped, manis quadruped.' (7)

A1.2 AcB.o: . (F) .: (x):xeB.*.--(Fx):*: (x):xeA.*.--(Fx)

Whatever is notinthegenusis notinthespecies.(9)

A2.1 AcB.o: (F):(jx). xeA.Fx.o. (fx) .xeB.Fx

Whatever is in thespeciesis necessarily in thegenus.'If manis good,

thenanimalalsois good.'(8)

*A2.2 A O. *: . (F). : (x)::xeA.O.,-(Fx):o: (x)::xEB.0. -(Fx)

It is notnecessary thatwhatisnotinthespeciesis notinthegenus.(10)

HereI haveinterpreted thespecies-genus relation intermsofclass-

inclusion, with'c' as the signof inclusion,'A' forthe nameof the

species,'B' forthe nameof the genus.This is somewhatmisleading,

sincenoteverysub-classof a genusis a species.However,it has the

meritofmakingclearthatthetwostatements Aristotle saysareneces-

sarilytrue(i.e. A1.2 and A2.1), correspond to laws or thesesin the

logicofclasses.I haveindicatedwithan asterisk(*) thosewhichAris-

totlesaysarenotalwaystrue.I use thecustomary 'e' forclass-mem-

bership, i.e. foran individualbelonging to a class; 'o' forimplication,

the dot '.' forpropositional conjunction;'--' forpropositional nega-

tion; 'F' fora predicatevariable,so that 'Fx' maybe read 'x is F';

'(x)' fortheuniversal quantifier; '(ax)' fortheexistential orparticu-

lar quantifier. Thusin A2.1,ifwe take'A' for'man,''B' for'animal,'

and 'F' for'is good,'wemayread:

'If manis included in animal, thenif,forsomex,x is a manandx is good,

then, forsome x,x is an animal andx is good.'

Whatthen,it maybe asked,doesAristotle meanby a Topic?He

givesno definition ofthetermin theTopics. However, in theRhetoric

he describes a Topicas an "elementofan enthymeme" (1396b23)and

in his philosophical dictionary in theMetaphysics(1014bl) he refers

to elements ofdemonstrations as "theprimary demonstrations eachof

whichis contained in manydemonstrations." The examplein our (8)

is an enthymeme. Furthermore, thewarrant forit,formalized in A2.1

mightwellbe described as beingcontainedin manyarguments, since

it canserveas warrant foranysimilarargument fromspeciestogenus.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

310 O[rO BIRD

Theophrastus offered a definition of a Topic whichhas beenpre-

servedin the commentary of Alexander:"A Topic is a principle

(arche) and element(stoicheon)fromwhichwe drawpropositions

thatserveas a basisforreasonings on a proposedquestion;it is de-

terminate as to circumscription (perigraphe . . . horismenos) and un-

determined as to particularapplications(kath' hekastaaoristos)"

(AA.II proem,126'4).Someoftheobscurity ofthislast clausewould

disappearifwe takeit as referring to thewarrants, forwhichwe have

givensymbolic equivalents. Each of theseis "determinate" in thata

definiterelationis understood, in thiscase thatof species-genus laid

downin ourfirst antecedent; yetit is "undetermined" in thatthewar-

rantitselfis nottherealizationof anyparticular genus-species rela-

tion.We geta definite ordeterminate genus-species relationonlywhen

thenamesofan actualgenusandspeciesaresupplied, i.e.whenvalues

aregivento thevariables.

In the textwe have been considering Aristotle is appealingto a

Topic fromGenusin orderto analysea problemregarding accident.

However,TopicsfromGenusare not restricted to any one kindof

problem.They may servealso to analyseproblemsof genus (e.g.

121a25),of property (e.g. 132a10),or of definition (e.g. 141b28).In

otherwords,thesameTopicmaybe usedto analyseanyone ofAris-

totle'sfourkindsofproblems. Sincethisis trueofotherTopics,there

is thusconsiderable repetition. This perhapsmorethananything else

accountsforthelengthand prolixity oftheTopics.Insteadofstating

a Topicgenerally, he statesit onlywithintheparticular contextof a

problemregarding one of thepredicables. Thus thesameTopicmay

be appealedto repeatedly. Aristotle makesno attemptto classifythe

Topicsforthemselves. In fact,hismaininterest in themseemsto lie

in theiraffording a meansforanalyzing thepredicables, i.e. theysub-

servehissubject-predicate logicofterms.

of theTopicsin Boethius

Classification

According to Regis,Aristotlestatesno lessthan337Topicalrules:

103 forAccidents, 81 forGenus,69 forProperty, 84 forDefinition

(R. 147,n. 1). In theenumeration thatLuciusgivesof themin his

1619editionI count287,whileBuhlein his 1792editioncounts382.

On anycountthereare a greatmany.It is thusno surprisethatan

effortwas madeto classifytheTopicsand to reducethemto a more

manageablenumber.The mostsuccessful of theseefforts,

judgedby

itshistorical is

influence, the one in

found Boethius.

Boethiushimself claimsno creditforit,butattributesit to others

whohavefoundwhathe callsanotherwayofviewingtheTopics.He

findsthisviewexemplified in Cicero'sTopics:

callsTopicsthosepropositions

Aristotle whicharemaximal anduniversal

andeitherper se necessaryor per se probable.

But sincetherearemany

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 311

suchpropositions, in facttheyare almostinnumerable, it is necessaryto

viewthemfroma higherperspective (ratiospeculationis).Witha careful

consideration we can investigatethedifferencesofall themaximaland uni-

versalpropositions and collecttheirinnumerable multitude intoa fewuni-

versaldifferences. Thus we may say thatsomeconsistin definition, others

in genus,and so on.Thus,forexample,all themaximalpropositions dealing

withdefinition willbe contained undertheonenameofdefinition....From

thisit is apparenthowthe Topica of Cicerodiffers fromthatof Aristotle.

For Aristotlediscoursesaboutmaximalpropositions, sincehe positsthem

as places (loci) of arguments.Cicero,however, understands by Topics,not

the maximalpropositions, but theircontaining difference.(BCT 1052BC;

1054B)

Boethius is here drawinga distinctionbetween what he calls a

Topical Maxim (maximapropositio)and a Topical Difference(differ-

entia maximaepropositionis).The Difference is in effectno morethan

the name under which a Topic is classified.Thus in Aristotle'stext

A1.1-1.2 fall underthe Topical Differenceof Genus, since theyargue

fromthe genus,whereasA2.1-2.2 fall underthe Differenceof Species

since theyargue fromthe species. The Maxims are the rules or war-

rantsforwhichwe have given formalizations. The distinctionrecalls

the definitionof a Topic givenby Theophrastus,the Differencecorre-

spondingto the "determinatecircumscription" and the Maxim to the

"undeterminedapplication."

To seek Topical Differencesis to classifythe Topics, and classifica-

tionis what Boethiusprovidesin his De differentiis topicis,whichbe-

came the sourceor auctoritasforthe doctrineof the Topics in medi-

aeval logic.In the secondof the fourbooksinto whichit is dividedhe

givesthe enumerationof Themistius,whosecommentary on Aristotle's

Topics is no longerextant.Transmittedby Peter of Spain, it became

the standardenumerationof the Topics in latermediaeval logic.

Enumerationof the Topics accordingto BDT II

I. Those drawnfromthetermsoftheQuaestio (i.e. IntrinsicTopics)

1. Definition

2. Description

3. Nominal Meaning

4. Whole:

4.1 Genus

4.2 Integral

4.3 In quantity

4.4 In mode

4.5 In time

4.6 In place

5. Part:

5.1 Species

5.2 Integral

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

312 OTrO BIRD

5.3 In quantity

5.4 In mode

5.5 In time

5.6 In place

6. Cause: Efficient, Material,Final, Formal

7. Effector Generation

8. Corruption

9. Use

10. Usual concomitants

II. Those extrinsicto the termsof the Quaestio

11. Opinionor Authority

12. Similars

13. The More

14. The Less

15. Proportion

16. Opposites:

16.1 Contrary

16.2 Privative

16.3 Relative

16.4 Contradictory

17. Transumption

III. Those that are mediateor mixedfromboth I and II

18. Case or Inflexion

19. Conjugates or coordinateexpressions

20. Division

The meaningof the variousTopics and of theirdivisioninto three

groupswillbe clearerafterconsiderationof theirappropriateMaxims.

But beforethat,it willbe usefulto see how Boethiuspresentsa Topic.

For that purpose we can considerhow he analyses the Topic from

Genus (BDT 1188BC) corresponding to that in Aristotle.All that he

says about it is containedin the followingtext:

(1) The Topic fromtheWholeas Genussuppliesarguments forques-

tionsin thisway:

(2) For thequestion,whetherjusticeis useful:

(3) Make the Everyvirtueis useful,justiceis a virtue,

syllogism: there-

forejusticeis useful.

(4) The questionhereconcerns accident,whether utilityis an accident

ofjustice.

(5) The Topicis thatwhichconsistsin theMaxim:Whatever is present

in thegenusis presentin thespecies.

(6) The Topic is fromthe Whole,i.e. fromGenus,sincevirtueis the

genusofjustice.

Since an argumentis forBoethiusthe determination of a quaestio,

he formulatesa questionin concreteterms(2) as soon as he has stated

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 313

whatTopic he is presenting (1). He thenformsan argument with

thoseterms,oftenas herein syllogisticform(3). Although he enumer-

ates theTopicswithoutmentioning thepredicables,Boethius,unlike

the mediaevallogicians,noteswhichpredicablehis questionis con-

cernedwith(4). He thencitesthe appropriate Topical Maxim (5)

and Difference

(6). SinceBoethiusnevercitesmorethanone Maxim

foranyoneTopicalDifference, it is worthnotingthatin thiscase he

givesonethatAristotlehadremarked is notalwaysvalid,namelyA1.1.

TopicalMaximsin PeterofSpain

The SummulaelogicalesofPeterofSpain (laterPope JohnXXI)

was thestandardelementary textin logicfromthelate XIIIth cen-

turyto theendoftheXVth.Of thetwelvetractatesintowhichit is

divided-thedodicilibelli,as Dante calls them(Paradiso12.135)

thefifth is devotedto theTopics.It is littlemorethana summary of

the firsthalfof BDT. The openingparagraphsgive the definitions

of thebasic termsused foranalysingarguments fromBDT I. Then

afterthedistinction betweenTopicalMaximand Difference (P 5.07)

we areprovidedwiththeenumeration oftheTopics.This is identical

withBDT II, exceptthatwhereasBoethiuscombines EffectandGen-

erationintoone,PeterofSpainseparatesthemand thusgetsa total

of 21 Topics insteadof 20; he also changesthe orderin whichhe

enumerates theExtrinsicTopics.UnlikeBoethius,however, Peterof

Spain givesconsiderable attentionto Topical Maxims.WhereasBo-

ethiuscitesonly25,PeterofSpain states,orindicateshowto formu-

late,a totalof81 Maxims.Thisincreased concern withMaximsis not

originalwiththeSummulae.It is also foundat leasta century earlier

in Abelard'streatiseon theTopicsin hisDialectica.

In analysing theTopicsPeterofSpainadoptsthefollowing proce-

dure: (1) He identifiestheTopic by nameand verybriefly describes

therelationwithwhichit is concerned. (2) He givesthe numberof

arguments andMaximsfallingundertheTopic,foreachofwhich(3)

he givesan examplein concretetermsofan argument usingtheTopic,

and (4) he statestheTopicalMaxim.In presenting hisanalysisI shall

followthesamepatternbutin abbreviated form.But since21 Topics

with81 Maximsstillexceedsthescopeofa singlearticle,I shallpass

overwithonlya briefnotetheTopicshavinglittleofformalinterest,

althoughI shallmentionall so as to providea completesurveyof

Peter'sworkon theTopics.In citingtheMaxims,I shallgivefirst my

formalization in modernnotation, followed by a literaltranslation

of

theMaximand oftheexamplegivenbyPeterofSpain.

P1. Definition

(P 5.10-5.11)

EightMaximsarecitedfordefiniensand definiendum(or fordefi-

nitioand definitum,

as theyarecalledbymediaevallogicians).These

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

314 OTTO BIRD

Maxims in effectestablishthe mutual replaceabilityof the one by the

other.It is sufficientto state the fourforthe definiens,since the four

forthe definiendumcan be obtained merelyby interchangingthese

two terms.Writing'B is definedby A' as 'B = dfA'

(1) B = dfA.o: (D) :AcD .O. BcD

Whateveris predicatedof the definiens is also predicatedof the definien-

dum:'A mortalrationalanimalis running, therefore

a manis running.'

(2) B = dfA.o:(D):DcA.o.DcB

Of whatever thedefiniens so is thedefiniendum:

is predicated, 'Socratesis

a mortalrationalanimal,thereforeSocratesis a man.'

(3) B = dfA.o:(D):r--(AcD).o.t--,(BcD)

Whateveris removedfromthedefiniens is also removedfromthedefinien-

dum: 'A mortalrationalanimal is not running, a man is not

therefore

running.

(4) B = dfA.o:(D):#-.'(DcA).o.r--(DcB)

Fromwhateverthe definiens is removedthe definiendumis also removed:

'A stoneis nota mortalrationalanimal,thereforea stoneis nota man.'

The last two have negatedthe antecedentsand consequentsof the

firsttwo. I have thereforeused the same termsforformalizing(2) and

(4), even thoughthe exampleof (2) has an individualname ('Socra-

tes') while that of (4) has a generalor class name ('stone').

The Maxims forthe Topics fromDescriptionand fromNominal

Meaning (a nominisinterpretatione)are the same as these,except

that for definiems and definiendumone substitutesrespectivelyde-

scriptioand descriptum,or interpretatioand interpretatum(P 5.12-

5.13)

P2. UniversalWhole,Genus, or Superior (P 5.16)

(1) AcB.*: .(F) .: (x) :xEB.o.-,.(Fx):o: (x) :xeA..,- (Fx)

Whateveris removedfromthegenusis also removedfromthespecies:'An

animalis notrunning, therefore a manis notrunning.

(2) AcB.o:(D):r%.'(DcB).o./-.-(DcA)

Removingthe genusalso removesthe species:'A stoneis not an animal,

therefore

a stoneis nota man.'

P3. Subjective Part, Species, or Inferior(P 5.17)

(1) AcB.o : (F):(yx) .xfA.Fx.o. (Jx).xEB.Fx

Whateveris predicatedof the speciesis also predicatedof the genus: 'A

manis running, therefore an animalis running.'

(2) AcB.o:(D):DcA.o.DcB

Of whatever thespeciesis predicated thegenusis also predicated:'Socrates

is a man,therefore Socratesis an animal.'

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 315

The consequent ofP3(2) is thelogicaltransposition oftheconse-

quentof P2(2). For thatreasonI have formulated themin thesame

terms,althougha generalname appearsin the exampleof the first

wherean individualnameappearsin the second.It mightbe noted

thatP2(1) andP3(1) areidenticalwithA1.2andA2.1,butAristotle's

othertwoTopics,whicharenotlogicaltheses,arenotmentioned. In-

steadPeterofSpainconsiders stillanotherrelationbetweengenusand

species.

OftheotherTopicsfromWholeandPartonlythosein Quantitate

and in Modo areofparticular Integralwholeis taken

logicalinterest.

in theordinary senseofphysicalwholeand part,suchas a houseand

its wallsand roof,and its Topic concerns arguingfromthe existence

of thiswholeto thatofits part,and thelogicaltransposition of this

(P 5.18). The TopicsfromWholeand Partin Place and in Timecon-

cernarguments using'everywhere,' 'nowhere,''always,''never.'The

TopicofWholein Quantity, however, providesan analogueofa basic

ruleofquantificationtheory.

P4. Wholein quantity(P 5.19)

(1) (x):xeA.o.Fx:o:yEA.

o. Fy

Whatever is predicated

ofa wholeinquantity

canalsobepredicated

ofany

ofitsparts:'Everymanruns, therefore

Socrates

runs.'

(2) (x): x6A..--(Fx):o:yd4. . -(Fy)

Whatever is removed

froma wholein quantity

is also removed

fromany

part:'No manruns,therefore

Socrates

is notrunning.'

P5. Part in quantity(P 5.20)

(1) FXI.FX2 ...Fxn.A -xl- X2 --N ** * - Xn- (y): yeA.>* Fy

Whateveris predicated

ofpartsin quantitytakentogether

is predicated

of

theirwhole:'Socrates

runs,Platoruns,

etc.,therefore

everymanruns.'

(2) --(FX1)

. -'(FX2) ...(Fxn) .A

=XI -~ X22*** 2 Xn-* (y): y-A.*j?*(Fy)

Whatever

is removedfrom partsinquantity

takentogether

is alsoremoved

fromtheirwhole:'Platodoesn'trunand thesameis trueof eachman,

hencenomanruns.'

P6. Wholein Mode and P7. Part in Mode (P 5.21)

By a Wholein Modeweareto understand a "universal

takenwith-

outdetermination." A Partin Mode is accordinglya "universal

taken

witha determination, suchas 'whiteman."'TheirMaximsaresaidto

be thesameas thoseforGenusandSpecies.If weinterpret thePartin

Mode,e.g. 'whiteman'as class-intersection,

and writeit 'A - B,' we

wouldaccordingly obtaintheappropriateMaximsbysubstituting this

for'A' in P2(1-2) and P3(1-2). PeterofSpain givesneitherMaxims

norexamplesfortheseTopics.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

316 orro BIRD

The TopicsfromCause and Effectgovernarguments fromone to

theotherand vice versa.ThosefromGeneration and Corruption gov-

ernarguments fromprocessto resultand areexemplified in: 'If what

is generated is good' (P 5.28). That from

is good,thenits generation

Use is muchthesame: 'Thatwhoseuseis goodis itselfgood'(P 5.30).

The Topic fromConcomitants concernsaccidentalqualitiesalways

foundtogether suchthatone can argue,e.g.'If oneis repentant, then

he has transgressed'

(P 5.31).

The TopicsfromOppositesgovernarguments fromone opposite

to anotherand are of thesamegeneralform,althoughfourdifferent

kindsofopposition aredistinguished.

ThatofRelativeOpposites states

a thesisin thelogicofrelationsand thatofContradictories expresses

a semantical propertywhichis in effect

a definitionof contradiction.

P8. RelativeOpposites(P 5.33)

(1) (gR)xRy:a: Qx)xED'R.o . (g/y)year'R

Positingoneoftworelatives positstheother:'A parent

is,therefore

a

childis.'

P9. Contradictory Opposites(P 5.36)

(1) T'p'i. .F'p'

Ifonecontradictory istruetheotheris false:"Socrates

sits'istrue,

there-

fore'Socratesdoesn'tsit'is false.'

The TopicsfromtheMore,theLess,theSimilar,fromProportion

and fromTransumption all involvereasoning fromanalogy.Typical

oftheirMaximsis theoneforSimilars:Aboutsimilars thereis a simi-

lar judgment(P 5.38). It is of someinterest thatBoethiusobserves

thatthewholeargument of Socratesin theRepublicexemplifies the

Topic fromTransumption, sinceit is based on justicein the state

beingmoreknownthanit is in theindividual(BDT 1192A).

The Topic fromAuthority warrantsarguments fromauthority

accordingto the Maxim: The expertis to be believedin his own

specialty(P 5.42).

The TopicsfromCase inflexion and Conjugatesare moregram-

maticalthantheothers.That ofConjugatesis exemplified in: 'If jus-

ticeis good,thenwhatis justis good';andthatfromCase inflexion in:

'If whatis justis good,thenwhatis donejustlyis donewell'(P. 5.45).

The TopicofDivisioninitsdichotomous formprovides thefollow-

inglogicallaw:

P10. Div?sion(P 5.45)

(1) A -A = V:o:xeA.o.x-e-A

If anytwodividecompletely,

positing

oneremovestheother:'Socrates

is eithermanornon-man,butheis notnon-man,therefore

heis man.'

The examplehereis JustoppositefromtheMaxim,i.e. 'non-man'

is firstremovedfrom'Socrates.'

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 317

Ockham'sRevisionof the TopicalTradition

In Boethiusand PeterofSpain we have foundlittlemorethana

classificationand enumeration of the Topics. The Topical Maxims

seemtobe viewedprimarily as inference-warrants, i.e.as rulesforcon-

structing arguments in

oncetermsare given somerelation.Boethius,

in fact,explicitly assignsthe Topicsto the logicof discovery rather

thanto thatofproof-i.e.to inventio, notto judicium(BDT 1173C).

Theyarelookedupon,thatis,moreas a meansforfinding arguments

thanas a meansfortheiranalysis.

Whenwe turnto thelogicof Ockham,however, we findthatthe

studyoftheTopicshasbecomeabsorbedintothelargerstudyofCon-

sequencesand has beensubjectedto an intensive logicalanalysisre-

sultingin a radicalrevision.I have elsewhere madea detailedstudy

ofthisrevision(cf.BIO). I shalldrawupontheresultsofthisstudy

to indicatehowtheTopicaltradition becomesalteredin theworkof

Ockham.

Ockhamis moreradicalthansomeofhis followers in thathe not

onlychangesor dropsmanyof the traditional Topical distinctions,

buthe alsoabandonstheverynameofTopicsas designating a distinct

divisionoflogic.BothAlbertofSaxonyand Buridan,whoareusually

classedas followers of Ockham,stillretainin theirlogicsa section

devotedto theTopics,in whichtheyenumerate and analysetheBo-

ethiantradition handeddownbyPeterofSpain.In Ockham, however,

thereis sucha changethat,unlessoneknowsthecontentofthattra-

dition,he mightwellmissthefactthatmostofhistreatiseon Conse-

quencesin hisgreatlogicis a re-working oftheTopics.Yet theplace

thatthis treatise

occupies in the Summa logicacorresponds to that

occupiedbytheTopicsin thetraditional arrangement ofthebooksof

theOrganon;namely,aftertheconsideration ofdemonstration in the

PosteriorAnalyticsand beforethat of fallaciesin the Sophistical

Refutations.

The treatiseon Consequences, whichcomprises the thirdof the

thirdpartof the Summalogica,is introduced as a consideration of

"arguments and consequences whicharenotin syllogistic form,i.e. of

sucha kindas areenthymemes" (OC 3-3.1,383). Earlier,in thetrea-

tiseon propositions, it had beennotedthatthe studyof conditional

propositions wouldbe deferred to thisparton thegroundthat"a con-

ditionalis equivalentto a consequence"(OC 2.31,315). Thus,since

it is in thispartthatwe findconsideration of thetraditional Topics,

the studyof theTopicshas beenbroughtunderthe studyof condi-

tionalpropositions. Ockhamis not the firstto notethisconnection.

Abelardin factlookedupontheTopicsas important primarily fora

studyofconditionals (AB 253; cf.BIF).

A conditional propositionis definedas "composed oftwocategori-

cals connected bymeansoftheconjunctive 'if' (si) orits equivalent"

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

318 OTTO BIRD

(OC 2.31, 315). Ockhamin factusually states the traditionalTopical

argumentswith the equivalent conjunctions'ergo' or 'igitur' ('there-

fore') and rarelywith 'si.' The firstpropositionof the conditionalis

called the antecedent,the secondthe consequent.Ockhammakesnine

distinctionswhichhe uses to classifythe consequences.These depend

forthe mostpart on different logicalfeaturesof antecedentand conse-

quent in a consequence.Thus they may be universalor particular,

affirmative or negative,or some combinationof these, and Ockham

systematicallyconsidersthe various combinations.

In this,however,thereis nothingpeculiar to a Topic. We finda

Topical considerationonly when we considerwhat validates the pas-

sage fromantecedentto consequent,or in Ockham'slanguage,through

what medium a consequenceholds. Accordingto Ockham, a conse-

quence holds eitherthroughan intrinsicmediumor an extrinsicme-

dium or throughboth. The text throughwhich he develops these

distinctionsreads as follows:

A consequence holdsthrough an intrinsic

medium whenit holdsbyvirtue

of someproposition formedfromthe same terms[as thosein the conse-

quence].Thusthisconsequence, "Socratesis notrunning, therefore a manis

notrunning," holdsby virtueofthismedium, "Socratesis a man"; forun-

lessthisweretrue,theconsequence wouldnotbe valid (nonvaleret).

A consequence holdsthrough an extrinsicmediumwhenit holdsthrough

somegeneralrulewhichno morerespectsthoseterms[in theconsequence]

thanany others.. . . It is through extrinsic

mediathatall syllogisms hold.

It mightbe objectedthatthepreviousconsequence, "Socratesis notrun-

ning,therefore a manis notrunning," holdsthroughthisextrinsic medium:

Fromthesingularto theindefinite and fromtheinferior to thesuperior with

a followingnegation, thereis a goodconsequence. But to thisit mustbe said

thattheconsequence holdsthrough thisextrinsic

mediummediatelyand as

it wereremotely and insufficiently,

becausein additionto thisgeneralrule

moreis required, namelythatSocratesis a man; andtherefore it holdsmore

immediately and sufficiently throughthis medium:"Socratesis a man,"

whichis an intrinsicmedium.(OC 3-3.1,383-384)

In this last distinctionOckham is in fact dealing with the tradi-

tionalTopics. That thisis so becomesevidenton consideringhis treat-

ment of the consequencethat correspondsto the Topics in Aristotle

withwhichwe began,namely,the Topic fromGenus. Since Ockham

has abandoned the traditionalclassification,

to findthe equivalentof

A1.2 we need to look in the sectiondealingwithconsequenceshaving

a negative antecedentand a negative consequence (OC 3-3.4, 390).

We findtherethe followingrule and examples:

Negativelyfroma distributed

superiorto a distributed

inferior

thereis a

simpleconsequence.

'No manis running, therefore

no whitemanis running.'

'No animalis running,

thereforeno ass is running.'

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 319

The examplesare thesameas thosethatPeterofSpain givesfor

Wholeand Part in Mode (P6) and forthe Topic fromGenus(P2).

In factOckham'srulecouldbe formalized in the same way as the

Maximforthe Topic fromGenusP2(1) whichcorresponds to Aris-

totle'sA1.2.However,we wouldapproximate morecloselyto theway

Ockhamformulates theruleifwe droptheuniversal predicatequanti-

fierandmovethenegationto thefront, thus:

01. AcB.0: (x).,-(xeB .Fx).o . (x).,-~(xe-4.

Fx)

Ockhamhas obviouslymovedfurther thanour previousauthors

towardsan extensionalpointofview.Thisis apparentin hisusingthe

relationratherthan that of genus-species,

superior-inferior which

enableshim to consolidateunderone rule two of Peterof Spain's

Maxims.But moreimportantly, it appearsin hisexplicitreference to

bywhichhe designates

distribution thequantification relationunder-

lyingthelogicallaw. Giventhatall A's are B's, it is becauseno x is

botha B andF thatwe knowthatno x is bothan A and F.

ApplyingOckham'sdistinctions to the above rule and example,

we obtainthefollowing lay-outforhis analysisofthiskindofconse-

quence:

Consequence:'No animalis running,

therefore

noassis running.'

(x)..- (xEB .Fx) .o . (x)., (xeA .Fx)

Intrinsicmedium:'Everyass is an animal.'

AcB

Extrinsic

medium: Negativelyfrom a distributed to a distrib-

superior

thereis a simple

utedinferior consequence.

AcB.0: (x). -(xeB .Fx).0 . (x).--(xeA .Fx)

It nowbecomesevidentwhatOckhammeansby sayingthatsuch

a consequence holdsimmediately throughthe intrinsic mediumand

mediately through theextrinsic medium.The consequence as it stands

is logicallycontingent; i.e. if we consideronlyits formas manifested

in theformalization, it is obviously possibleto findvaluesforthevari-

ableswhichwillfalsify it and otherswhichwillverify it. If,however,

we consider thesemantical relationbetweentheconcrete termsin the

consequence and expressthisin theintrinsic medium, then,takingto-

gethertheintrinsic mediumand the consequence, we have a logical

law,namely,thatexpressed in theextrinsic medium.By formalizing

them,we can see at once thatthe intrinsic mediumand the conse-

quencehavethesameformas themainantecedent and consequent of

theextrinsic medium.In effect, theexpression oftheintrinsic medium

amountsto theassertion oftheantecedent oftheextrinsic mediumso

thatbyapplyingtheruleofdetachment, ormodusporene,theconse-

quentcan be assertedindependently as theconsequence.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

320 01rro BIRD

The languageOckhamuses forthesedistinctions is the same as

thatusedforthemaindivisionsoftheTopicsin Boethiusand Peter

of Spain.Sinceit preserves something ofthesamefunction, it seems

clearthatOckhamis revising thosedistinctions forhis ownpurposes.

However, thereis nolongeranyreference to TopicalMaximandTopi-

cal Difference. Whathe calls the rule (regula) expressedin the ex-

trinsic mediumobviously correspondsto theTopicalMaxim.But from

thisit doesnotfollowthattheintrinsic mediumcorresponds in every

respectto the TopicalDifference. It obviouslydoes to some extent,

sincethestatement ofit in theaboveexampleis equivalentto saying

that'animal'is superior or genusto 'ass' as inferior or species.How-

ever,Ockhamconsidersit important to distinguish the two.In the

proposition, 'Everyass is an animal,'Ockhamwouldpointout that

thesubjecttermis in personaland significative supposition, i.e. 'ass'

has its usual reference. But in theproposition, "'Ass' is a speciesof

the genus'animal',"thesubjecttermis takenin simplesupposition,

i.e. it doesnothave its usual reference, but is understood foran in-

tentiomentis, i.e. 'ass' is nowon a different semanticlevelfromwhat

it wasbefore. Thisdifference Ockhamthebasisfordistinguish-

affords

ingstillfurther amongconsequences.

However,beforeturningto that,we shouldnotethatin stating

rule01, Ockhamdeclaresthatit providesus witha "simpleconse-

quence"(consequentia simplex).Bythishemeansa conditional propo-

sitionthatis logicallytrue,or,as he says,one "in whichat no time

can theantecedent be truewithouttheconsequent" (3-3.1,383). It is

tobe distinguished froma factualconsequence (consequentia utnunc)

whichis one thatcan be falsified, i.e. one "in whichthe antecedent

can be trueat sometimewithoutthe consequent beingtrue."With

this distinction Ockhamis able to sortout the necessaryTopical

Maxims,or extrinsic media,fromthosethatare onlyprobable.Aris-

totle, as we have seen fromourfirst text,includesbothin hisanalysis

and,at leastin somecases,carefully distinguishes thetwo.Boethius

notesexplicitly the difference, but he does littleto distinguish the

necessary fromtheprobableTopics (BDT 1195AB).Peterof Spain

does not evenmentionit. Withthe singleexceptionof Abelard(cf.

BIF), I knowofno onebeforeOckhammakinga systematic effort to

distinguish thetwo.

A logicallynecessaryproposition remainstrueno matterwhat

termsit is expressed in so longas thesameformis preserved, as Ock-

hamsaysofwhathe callstheextrinsic medium.Most ofthoselisted

by Ockham,however, arein factdiscovered orintroduced through an

analysisof particular terms,suchas definiens-definiendum, superior-

inferior, whole-part-those namelyconsidered in the Topical tradi-

tion.However,in his analysisof theseOckham,likeAbelardbefore

him,discovers lawsofthelogicofpropositions. To thesehe devotesa

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 321

(3-3.37), underthe

separatechapterin thetreatiseon consequences

titleof "GeneralRules of Consequences."In it he considerssuch

rulesas:

02. p*(-ipoq)

Fromthefalsea trueproposition

canfollow.

03. (p*q) (--qO---p)

Fromtheopposite oftheantecedent

theopposite

oftheconsequent follows.

These ruleshave been carefully studiedby Salamucha,Bochenski,

Boehner,Moodyas Ockham'spropositional logic.They differ from

whatwe maycall the Topicalconsequences in thattheydo not de-

pendfortheirforceupona term-relation-what in ourformalizations

of the Maximsis designated in the mainantecedent, e.g. 'B - dfA,'

'A c B,' etc.Thisis neededforthelogicalnecessity ofthewhole,since

withoutit theconditional proposition thatfollowsin themainconse-

quentis logicallycontingent. Suchterm-dependent consequences con-

stituteby farthe largestpartof Ockham's treatise

on consequences.

To completethe analysisof Ockham'srevisionof the Topicsone

moredistinction is needed-thatalreadyreferred to as regarding dif-

ferent kindsofsupposition. According to Ockham,we have a distinct

kindofconsequence, different

fromanywehavelookedat so far,when

thepredicateoftheconsequent is thenameofone of thepredicables

and thereby putsitssubject-term in simplesupposition (03-3.1,384).

In sucha consequence thereis theidentification ofa termwithoneof

thepredicables, or thenegationofthis.Thenin place of an extrinsic

mediumsuchas we havebeenconsidering, we havea rulesuchas the

following:

04. If a predicateis notpredicated ofa subjecttakenuniversally

that

predicateis notthegenusofthatsubject.(34.18,427)

Withthisdistinction Ockhamin effect re-uniteswhatmightbe

called the Aristotelian and the Boethiantraditions on the Topics.

Aristotleused the Topics to analyseproblemsregarding accident,

genus,species,property, definition,i.e.whatlateron arecalledthefive

predicables. WithBoethiusthisconnection withtheTopicsis all but

dropped, and in Peter of Spain it has disappearedentirely.This Bo-

ethiantradition of theTopicspredominated in mediaevallogic.The

textof Aristotle's Topics was not knownuntilafterthe mid-XIIth

century, butevenafteritsrecovery Boethiuscontinued, perhapsaided

bytheinfluence ofPeterofSpain,to be themainauthority. Ockham,

however, takesaccountofbothas involving distinctconcerns.Under

consequences whoseconsequent has its subject-termin simplesuppo-

sitionand itspredicate-term thenameofoneofthepredicables, Ock-

ham systematically analysesthe Aristotelian Topics and formulates

its rulesas devicesforidentifying and testingwhether a termis one

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

322 orrO BIRD

of thepredicables.

He does thisin chapters17-30 afterhe has con-

sideredconsequencesin personalsupposition

underwhichhe includes

theBoethiantraditionoftheTopics.

Conclusion

To attemptin conclusion a synoptic view,it can be claimedthat

thestudyoftheTopics,at leastalongthelinethatwe havebeenfol-

lowing, underwent a progressive In Aristotle

formalization. theTopics

are devicesforfinding and analysinghowvariouskindsof predicates

maybe attributed to a subject.Throughthisconcernforpredicables

theyare subordinated to a subject-predicatetheoryof thoughtand

discourse.However,the languagethat Aristotleemploysin talking

abouttheTopics,evenapartfromtheexplicitconcern withquestion-

ingand answering in TopicsVIII, suggeststhathe is viewingthem

primarily withinthe contextof a theoryand methodof discussion.

One oftheveryfewhistorical studiesoftheTopics-that by Thion-

villein 1855-evengoesso faras to suggestthatthediscovery ofthe

Topicsresultedfroman effort to reduceto principlethe procedures

employed in discussion in thePlatonicdialoguesand presumably also

in theAcademy(T 75).

With Boethiusthe Topics have becomesystematically classified,

termshavebeenintroduced foranalyzingthem,and whatis ofgreat-

estlogicalsignificance in themhas beenstatedin a seriesofMaxims.

In thesummary of themin Peterof Spain theyhave beenremoved

entirely fromconcern withthepredicables. Less richand diversethan

in Aristotle, particularly in mattersof linguisticanalysis,theyhave

becomean objectof special analysis,and the othermaterialwith

whichtheywereassociatedin Aristotlehas eitherbeen droppedor

relegated to othertreatises.

From the startthe Topics had to do witharguments and the

maximsor rulesforvalidatingthem.In Ockhamtheybecomesub-

sumedunderthestudyof logicalconsequence considered firstin the

formof a conditional proposition. Theyare distinguished bothfrom

syllogisticconsequenceand froma purelyformalconditional whose

truthin no waydependsuponthetermsfromwhichit is composed.

Topical arguments or consequences are thosethat dependfortheir

validityupona semantical relationbetweentheirsignificantterms.To

thisextenttheyare notpurelyformal.However,thisis notto imply

thattheyare totallywithoutformalelements.The rule,maxim,or

extrinsic mediumthatvalidatesa Topical consequencemay consti-

tutea purelyformalrule,i.e. a logicallaw.Aristotle appreciated this,

as we have seen,and in distinguishing simplefromfactualconse-

quencesOckhamsortsout thelogicallynecessary fromtheprobable.

In thisrespecttheancientTopicalanalysismaycontribute to con-

temporary logicaldiscussion. In comparisons betweenformal logicand

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOGICAL TOPICS: ARISTOTLE TO OCKHAM 323

ordinarylanguageconsiderable emphasisis sometimes placed upon

the importance of non-formal procedures as somehowextra-logical.

Thusit has beenurgedthat"a typicalinstanceofa non-formal conse-

quencerelation"thatescapesformalanalysisis providedin thesen-

tence: "'x is red' implies'x is colored"' (AM 35). It is just such

sentencesas thisthatthe Topicsare devisedto analyse.In fact,we

have herea species-genus relation.This relation,it maybe claimed,

sinceit doesnotbelongto logicto knowthat'red'is a

is extra-logical,

speciesof 'color.'However,oncethisis given,theformallogiciancan

inquireinto whatit is that warrantsthe inference, and, following

Topical analysis,he can providein P3(2) a rule whichis in facta

proposition offormallogic.

UniversityofNotreDame.

TABLE OF REFERENCES

A Aristotle,

Topica,in Organum, ed. LudivicusLucius (Basel, 1619); Topica,

in OperaOmnia,ed. T. Buhle (Zweibrucken, 1792); Topica,trans.W. A.

Packard-Cambridge (Oxford,1928).

AA Alexander Aphrodisias,In Aristotelis Topicorum Librosocto Commentaria,

ed. M. Wallies(Berlin,1891).

AB Abelard,Dialectica,ed. L. M. De Rijk (Assen,1956).

AM AliceAmbrose, "The Problemof LinguisticInadequacy,"in Philosophical

Analysis,ed. M. Black (Ithaca,1950),15-37.

BCT Boethius, In TopicaCiceronis Commentaria, Migne,PatrologiaLatina,t. 64.

BDT Boethius, De DifferentiisTopicis,loc. cit.sup.

BIF OttoBird,"The Formalizing oftheTopicsin MediaevalLogic,"NotreDame

Journalof FormalLogic,I (1960), 138-149.

BIO OttoBird,"Topicand Consequence in Ockham'sLogic,"NotreDame Jour-

nal ofFormalLogic,II (1961),65-78.

BIR OttoBird,"The Re-Discovery oftheTopics: Professor Toulmin'sInference-

Warrants," Mind,LXX (1961), 534-539.

OC Ockham,SummaLogicae,ed. P. Boehner(St. Bonaventure, 1951,1954),2

vols.,continuouspagination,butstillincomplete, reachingonlythe1stofthe

3rdpart.For Pt. 3-3, I cite: Summatotiuslogicae(Oxford,1675).

P PeterofSpain,Summulaelogicales, ed. I. M. Bochenski(Rome,1947).

R L. M. Regis,L'opinionselonAristote(Ottawa,Paris,1935).

De la theoriedes lieuxcommuns

T E. Thionville, dansles Topiquesd'Aristote

et des principalesmodifications qu'elle a subiesjusqu'a nos jours (Paris,

1855).

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.245 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 10:07:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Mind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundDocumento13 pagineMind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Nietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OneDocumento16 pagineNietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OnemehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Newspaper TemplateDocumento6 pagineNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Kantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocumento12 pagineKantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediamehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Liberal Arts Speech8Documento16 pagineLiberal Arts Speech8mehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- ATA585-2017Fall SyllabusDocumento4 pagineATA585-2017Fall SyllabusmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocumento24 pagineJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Newspaper TemplateDocumento6 pagineNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Social OntologyDocumento771 pagineSocial OntologyJoey Carter100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Ash - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD ThesisDocumento661 pagineAsh - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD Thesismehmetmsahin100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocumento11 pagineBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Critique of DuerrDocumento6 pagineCritique of DuerrmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocumento11 pagineBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Zuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFDocumento16 pagineZuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Walton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingDocumento7 pagineWalton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- İlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookDocumento35 pagineİlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocumento24 pagineJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Strauss ModernitysThreeWavesDocumento9 pagineStrauss ModernitysThreeWavesV_ctor_Manuel__7561Nessuna valutazione finora

- Syrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationDocumento10 pagineSyrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Otto Bird - The Re-Discovery of The TopicsDocumento7 pagineOtto Bird - The Re-Discovery of The TopicsmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Sayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The QuranDocumento4 pagineSayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The QuranmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Stack - Value and FactsDocumento12 pagineStack - Value and FactsmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ps 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014Documento20 paginePs 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014mehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Schutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesDocumento17 pagineSchutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Tastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchDocumento12 pagineTastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodDocumento17 pagineThe Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodmehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Baber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15Documento4 pagineBaber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15mehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ernst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistoryDocumento3 pagineErnst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistorymehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Dhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisisDocumento8 pagineDhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisismehmetmsahinNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial ReportDocumento52 pagineIndustrial ReportSiddharthNessuna valutazione finora

- بتول ماجد سعيد (تقرير السيطرة على تلوث الهواء)Documento5 pagineبتول ماجد سعيد (تقرير السيطرة على تلوث الهواء)Batool MagedNessuna valutazione finora

- L GSR ChartsDocumento16 pagineL GSR ChartsEmerald GrNessuna valutazione finora

- SSC Gr8 Biotech Q4 Module 1 WK 1 - v.01-CC-released-09May2021Documento22 pagineSSC Gr8 Biotech Q4 Module 1 WK 1 - v.01-CC-released-09May2021Ivy JeanneNessuna valutazione finora

- Principled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Documento24 paginePrincipled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Jeremias GordonNessuna valutazione finora

- Point and Figure ChartsDocumento5 paginePoint and Figure ChartsShakti ShivaNessuna valutazione finora

- AP8 Q4 Ip9 V.02Documento7 pagineAP8 Q4 Ip9 V.02nikka suitadoNessuna valutazione finora

- CIPD L5 EML LOL Wk3 v1.1Documento19 pagineCIPD L5 EML LOL Wk3 v1.1JulianNessuna valutazione finora

- Designed For Severe ServiceDocumento28 pagineDesigned For Severe ServiceAnthonyNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFDocumento12 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Unit 2: Air Intake and Exhaust SystemsDocumento10 pagineUnit 2: Air Intake and Exhaust SystemsMahmmod Al-QawasmehNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pneumatics of Hero of AlexandriaDocumento5 pagineThe Pneumatics of Hero of Alexandriaapi-302781094Nessuna valutazione finora

- Functions of Theory in ResearchDocumento2 pagineFunctions of Theory in ResearchJomariMolejonNessuna valutazione finora

- Configuration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Documento117 pagineConfiguration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Dikdik PribadiNessuna valutazione finora

- 23 Ray Optics Formula Sheets Getmarks AppDocumento10 pagine23 Ray Optics Formula Sheets Getmarks AppSiddhant KaushikNessuna valutazione finora

- CL Honours Report NamanDocumento11 pagineCL Honours Report NamanNaman VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleDocumento76 pagineBring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleAkoumpakoula TampaoulatoumpaNessuna valutazione finora

- "Organized Crime" and "Organized Crime": Indeterminate Problems of Definition. Hagan Frank E.Documento12 pagine"Organized Crime" and "Organized Crime": Indeterminate Problems of Definition. Hagan Frank E.Gaston AvilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Blake Mouton Managerial GridDocumento3 pagineBlake Mouton Managerial GridRashwanth Tc100% (1)

- English Test For Grade 7 (Term 2)Documento6 pagineEnglish Test For Grade 7 (Term 2)UyenPhuonggNessuna valutazione finora

- SDS ERSA Rev 0Documento156 pagineSDS ERSA Rev 0EdgarVelosoCastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Sim Uge1Documento62 pagineSim Uge1ALLIAH NICHOLE SEPADANessuna valutazione finora

- Agma MachineDocumento6 pagineAgma Machinemurali036Nessuna valutazione finora

- National Interest Waiver Software EngineerDocumento15 pagineNational Interest Waiver Software EngineerFaha JavedNessuna valutazione finora

- Meta100 AP Brochure WebDocumento15 pagineMeta100 AP Brochure WebFirman RamdhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Sony x300 ManualDocumento8 pagineSony x300 ManualMarcosCanforaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application TechniqueDocumento50 pagineEthernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application Techniquegnazareth_Nessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsDocumento26 pagine12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsKristinDaigleNessuna valutazione finora

- Supply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedDocumento6 pagineSupply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedknhartNessuna valutazione finora

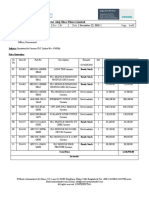

- LC For Akij Biax Films Limited: CO2012102 0 December 22, 2020Documento2 pagineLC For Akij Biax Films Limited: CO2012102 0 December 22, 2020Mahadi Hassan ShemulNessuna valutazione finora