Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ehll Phoenician Punic PDF

Caricato da

Rodrigo MendesTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ehll Phoenician Punic PDF

Caricato da

Rodrigo MendesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

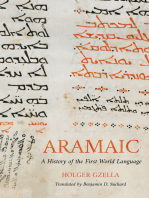

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

HEBREW LANGUAGE

AND LINGUISTICS

Volume 3

PZ

General Editor

Geoffrey Khan

Associate Editors

Shmuel Bolokzy

Steven E. Fassberg

Gary A. Rendsburg

Aaron D. Rubin

Ora R. Schwarzwald

Tamar Zewi

LEIDEN BOSTON

2013

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

Table of Contents

Volume One

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ vii

List of Contributors ............................................................................................................ ix

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... xiii

Articles A-F ......................................................................................................................... 1

Volume Two

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Articles G-O ........................................................................................................................ 1

Volume Three

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Articles P-Z ......................................................................................................................... 1

Volume Four

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Index ................................................................................................................................... 1

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

phoenician/punic and hebrew 71

*qbrv > *qbr > q,r grave (like *klbv > References

k,l dog) versus *qibr > qir my Bauer, Hans and Pontus Leander. 1922. Historische

grave; and feminine participles of the shape Grammatik der hebrischen Sprache des Alten

k; Testaments. Halle: Niemeyer.

z<qn old, but construct zqan; and Ben-ayyim, Zeev. 19881989. Remarks on Philip-

similarly constructs of the form miqal from pis law (in Hebrew). Lonnu 53:113120.

maql nouns, such as mirba resting- Bergstrsser, Gotthelf. 1918. Hebrische Gramma-

place < absolute marb (Brockelmann tik. Vol. 1. Leipzig: Vogel.

1908: 108, 147). Blake, Frank R. 1950. The apparent interchange

between a and i in Hebrew. Journal of Near East-

ern Studies 9:7683.

Philippis Law is, however, notorious for hav- Blau, Joshua. 1981. On pausal lengthening, pausal

ing as many exceptions as examples: stress shift, Philippis law and rule ordering in

Biblical Hebrew. Hebrew Annual Review 5:114

alongside imperfect tln< we nd imperative (reprinted in idem, Topics in Hebrew and Semitic

ln< go (fpl)!, and rather than a in the linguistics, 3649. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1998).

feminine plural imperfect forms of hifil and some . 1986. Remarks on the chronology of Philippis

piel verbs; law (in Hebrew). Proceedings of the Ninth World

with the alleged development *bntv > *batt Congress of Jewish studies, Jerusalem, August

> ba above, compare *ntv > *itt > 412, 1985. Division D, vol. 1: Hebrew and other

time, and nearly all nouns of the pattern *qill, Jewish languages, 14. Reprinted in idem, Studies

whose reex in Tiberian Hebrew is ql, not qal as in Hebrew Linguistics (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1996),

predicted by Philippis Law, such as *immv > 1216.

*m mother; *libbv > l heart; Brockelmann, Carl. 1908. Grundriss der vergleichen-

with the alleged development *qbrv > *qbr > den Grammatik der semitischen Sprachen. Vol. 1.

q,r above, compare *tsprv > *spr > Berlin: von Reuther.

s<r book. Harviainen, Tapani. 1977. On the vocalism of the

closed unstressed syllables in Hebrew: A study

based on the evidence provided by the transcrip-

The only forms to which Philippis Law applies tions of St. Jerome and Palestinian punctuations

with some degree of consistency, in fact, are (Studia Orientalia 48/1), 1621. Helsinki: Finnish

those of the perfect and imperfect verb para- Oriental Society.

Lambdin, Thomas O. 1985. Philippis law reconsid-

digms in which the Proto-Semitic theme vowel ered. Biblical studies presented to Samuel Iwry,

*i in an originally closed, accented syllable ed. by Ann Kort and Scott Morschauser, 135145.

appears in Tiberian Hebrew as pata, forms Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Philippi, Friedrich W. M. 1878. Das Zahlwort Zwei

such as z<qnt and tln<, and

im Semitischen. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Mor-

even in the latter the sound change to a is often genlndischen Gesellschaft 32:2198.

blocked by paradigmatic pressure, especially in

the derived stems. John Huehnergard

(University of Texas at Austin)

Some Hebraists, following Philippi, have

maintained that the sound rule operated early

in the history of Hebrew (e.g., Bergstrsser

1918:149; Ben-ayyim 19881989). Blau Phoenician/Punic and Hebrew

(1981; 1986), however, established a relative

chronology in which pausal lengthening must 1. I n t r o d u c t i o n

precede Philippis Law, so that the latter must

therefore be relatively late in the development Hebrew and Phoenician (along with Punic,

of Hebrew. Likewise, in a methodologically on which see below) belong to the Canaanite

innovative paper, Lambdin (1985) showed that group of North-West Semitic ( Northwest

the rule did not operate in all attested varieties Semitic Languages and Hebrew), though no

of Biblical Hebrew (such as those exhibited consensus exists on how closely related the two

by Babylonian vocalization and by the Greek dialects/languages may be. According to dialect

transcriptions of Origens Hexapla), and thus geography, Garr (1980) speaks of a dialect

must have operated rather late in the history of chain sweeping across all the Canaanite and

Tiberian Hebrew. Lambdin also showed that Aramaic dialects (before the Persian period),

the phonetic history of the Segholates was with Phoenician at one linguistic extreme, Ara-

at least partly determined by the nature of the maic at the other and Hebrew as a minor lin-

medial root consonant. guistic center. In historical perspective, Ginsberg

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

72 phoenician/punic and hebrew

(1970) places Phoenician and Ugaritic in the Phoenician colonies would be called Poeni by

Phoenic sub-group within Canaanite, with their Latin-speaking Roman neighbors; and

Hebrew and the Transjordanian dialects clas- from this term derives the modern scholarly

sied together in the Hebraic sub-group; while term Punic to refer to the stage of the Phoeni-

Rainey (2007), somewhat in line with Gins- cian language used in the West under Carthag-

berg (though not concerning Ugaritic), sees inian hegemony (Amadasi Guzzo 2005).

even stronger links between Hebrew and the In Phoenician/Punic we recognize different

Transjordanian dialects, with a concomitant dialects and phases distinguished by ortho-

argument against a close Hebrew-Phoenician graphic (in many cases representing phono-

relationship. In any case, after Hebrew, Phoe- logical), morphological, and, to a lesser degree,

nician/Punic is the best known dialect/language lexical features. In Phoenicia proper, Standard

of the Canaanite group. Moreover, regardless Phoenician (or Tyro-Sidonian) is attested from

of which classication schema one adheres to, about the 9th to the 2nd (or perhaps 1st)

almost all scholars would agree that Hebrew century B.C.E., though some of the important

and Phoenician were characterized by a cer- inscriptions in this dialect come from Cyprus

tain amount, if not a high degree, of mutual and Anatolia (e.g., the aforementioned Kara-

intelligibility. tepe). However, attested earlier is the Byblian

The rst known Phoenician inscriptions dialect (Amadasi Guzzo 1994; Gzella forth-

belong to the 11th century B.C.E. (cf. Lemaire coming) which has two phases: a) an ancient

20062007; Rollston 2008, against Sass 2005). one attested mainly in the 11th-century (?)

As such, Phoenician is attested slightly earlier Arm sarcophagus (more archaic than the

than Hebrew, whose rst inscriptions date to following documents), and by a group of royal

the 10th century B.C.E. Hebrew eventually inscriptions from the 10thearly 9th century;

achieved a long and extensive literary tradition and then, after a gap, b) a series of Persian-

(cf. the biblical books especially), while Phoe- period (late 6thlate 4th century B.C.E.)

nician is known only from inscriptions. The inscriptions reecting the inuence of Standard

Phoenician epigraphic corpus comprises several Phoenician. In the West, a Punic phase devel-

hundred texts from the Levant and neighboring oped from Phoenician starting with the early/

lands, some of which (e.g., Karatepe and Incirli) mid-6th century B.C.E. After the destruction of

are quite extensive, and reaches approximately Carthage (146 B.C.E.), we speak of Late Punic

7000 texts when one includes the Punic mate- for the language which is still written in Punic

rial. The epigraphic material has been published script until the 2nd century C.E. (as proven by

over the course of more than a century in the KAI 173 from Sardinia, mentioning the name

two series Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum of the emperor Antoninus Pius [r. 138161]; cf.

(CIS I; 1881) and Rpertoire dpigraphie Amadasi Guzzo 1999; Sznycer 1999; Jongeling

Smitique (RS; 1900), with selections of the 2008). The language survived for at least three

most important texts collected in works such as more centuries, however, since the writings

KAI and Gibson 1982. of St. Augustine (354450), who hailed from

The Greeks referred to the inhabitants of Hippo in modern-day eastern Algeria, demon-

coastal Lebanon and northern Israel, and pre- strate that Punic was still spoken in his day.

sumably of inland southern Syria as well, as Proposals for more detailed dialect divisions

Phoeniciansthough they probably called than that offered here (see, e.g., Garbini 1988)

themselves Canaanites. The language and its are based mainly on the geographic distribution

speakers spread quickly: by the 9th century of the inscriptions.

B.C.E. Phoenician travellers had already reached The Phoenicians used a 22-letter alphabet,

southern Anatolia, Egypt, Cyprus, Crete, Rho- which in turn was borrowed by the Israel-

des and other Aegean islands, and probably ites and all others in the Levant (Arameans,

Mainland Greece. From the rst half of the 8th Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites, Philistines).

century B.C.E., they founded towns (colonies) In the West, a Punic variant of the Phoenician

on Cyprus and in the Western Mediterranean, script developed, especially under Carthagin-

most importantly Carthage, near modern-day ian inuence. The script which prevailed in

Tunis (founded according to tradition in 814 the Late Punic phase is a cursive variant of the

B.C.E.). Eventually the people of these western Phoenician alphabet, called Neo-Punic. It is

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

phoenician/punic and hebrew 73

important to note that while the scribes who , <n< year < *anat), though one must

wrote Hebrew, Aramaic, etc., developed matres admit that this feature is characteristic of Ara-

lectionis to indicate vowels, especially long maic as well.

vowels, this practice was not adopted by Phoe- As noted, Phoenician and Hebrew are closely

nician scribes, who apparently were much more related and typologically similar. Nonetheless,

conservative in their approach. As a result, a many recognizable differences exist. In what

form such as mlkt is ambiguous, with follows, we list some of these distinctions,

possible meanings including (but not limited to) concentrating on phonology and, to a lesser

I ruled and you ruled, though, fortunately, extent, morphology, syntax, and vocabulary.

context usually helps to resolve potential ambi- On occasion, we cite parallels from Hebrew,

guities. Only in the Late Punic texts do vowel especially from compositions presumed to be

letters appear, most likely under the inuence written in IH, such as the sections of Kings that

of Greek and Latin orthography. describe the northern kingdom of Israel (Rends-

Other sources for Phoenician include the burg 2002), the stories of the northern judges

transcriptions of personal names in Egyptian, (Rendsburg 2003), the book of Proverbs (Gins-

Assyrian, Greek, and Latin. We also have a berg 1982:3536), selected psalms (Rendsburg

ten-line speech in Punic preserved in Plautus 1990), and others. These IH features represent

Latin comedy Poenulus (Sznycer 1967; Grat- grammatical and lexical isoglosses linking IH

wick 1971), some Punic inscriptions written in and Phoenician.

the Greek alphabet, and about fty so-called

Latino-Punic inscriptions (2nd5th century 2. P h o n o l o g y

C.E.), that is, texts written in the Punic lan-

guage using Latin letters. Each of these sources Phoenician had 22 consonants, represented by

provides information about the late phases of 22 alphabetic signs. Hebrew possessed the addi-

the language (Kerr 2010). tional phonemes //, /x/ and // (Blau 1982),

Our knowledge of Phoenician/Punic remains which did not exist in Phoenician. In the course

partial because of the limited sources, the pres- of its development, Phoenician/Punic merged

ent lack of a real literature, and the nature of // with /s/; cf. the Phoenician transcriptions

the writing system. The language must be partly ptlmys and ptlmy for Greek

reconstructed based on comparison with related (KAI 19.5, 67 and KAI 42.2; 43.4,

languages, especially with the better known 6, 7, 8). However, some Latino-Punic inscrip-

Hebrew. By contrast, the contribution of Phoe- tions apparently distinguish between the two

nician to our understanding of Hebrew is very phonemes and use the Greek character for

limited. In some instances, Phoenician helps to //, but Latin S for /s/. Compare Latino-Punic

account for specic Hebrew features, especially umar watcher (KAI 179.3), correspond-

those characteristic of Israelian (i.e., northern) ing to Hebrew mr (see further PPG3

Hebrew (henceforth IH). This is due to a) the 4348). Somewhat surprisingly Greek ren-

geographical proximity between northern Israel derings of the names of the two large Phoenician

and Phoenicia, b) cultural inuence between city-states present different letters, even though

the two, especially in the direction of Phoenicia both begin with the same Phoenician (though

over Israel (as attested archaeologically in some apparently not Proto-Semitic) consonant //,

northern Israelite sites), and c) the intermar- viz., Tyre (for r) and Sidon

riage of the royal families, as described in the (for dn) (PPG3 11 note; see also Steiner

Bible specically for Ahab, king of Israel, and 1982:6667). Peculiar to Phoenician/Punic is

Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal of Tyre (even if the the tendency for voiced /z/ (<*) to become

Bible uses the term Sidonian [1 Kgs 16.31]). voiceless /s/, as in skr he remembered

The best examples of features shared by (Hebrew z<ar) and Late Punic st this

Phoenician and northern Hebrew come from (m. and f.) (cf. Hebrew z this [f.]).

the Samaria ostraca: a) monophthongization As in Hebrew, stops tended to become frica-

of the diphthong ay > , as reected in yn tives, without following, however, the rules

wine (cf. Biblical Hebrew [reecting Judahite established for Tiberian Hebrew (for this rea-

Hebrew] yayin); and b) the use of at son, in the conventional reconstruction of

year (< *att < *ant) (cf. Biblical Hebrew Phoenician/Punic words, these consonants are

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

74 phoenician/punic and hebrew

usually transcribed, regardless of their position long vowel, the original -h sufx was written

within the word, as stops and not as fricatives). -w, e.g., l-dtw /l-adttiw/ < /*la-adttiu/

In particular, there is not enough evidence for < /*la-adtti-h/ for his lady.

the entire set of the so-called bgdkpt letters. In Phoenician/Punic, the sufx pronoun of

The development is clear for /p/, which in Late the 3rd masculine and feminine plural, /-humu/

Punic was always pronounced [f], even at the and /-hima/, respectively, also had two variants:

beginning of words, e.g., Latino-Punic fel he did after an original -u or -a, these were /-m/ and

(IRT 873.2) versus Hebrew p<al. Concern- /-m/, respectively, both written - -m, e.g.,

ing /k/ and /t/, only in the West from the 3rd zrm /zarm/ < /*zara-humu/ their (m.)

2nd century B.C.E. do Greek and Latin tran- seed and msprm /misparm/ < /*mis-

scriptions of Phoenician/Punic words attest to parahima/ their (f.) number. After -i or a long

the regular fricative pronunciation (for details, vowel, these sufxes were written - -nm,

see PPG3 37). For the other stops, the devel- for masc. /-nm/ and fem. /-nm/, e.g.,

opment is less certain (cf. PPG3 38 and 41). l-dnnm /l-adninm/ for their (m.) lord;

As in Hebrew, /n/ normally assimilates before lknnm /lakninm/ for their (f.) being (KAI

another consonant. In Punic, however, there is 14.20). The origin of the variant - -nm is

a strong tendency to secondary dissimilation, as unclear. Again, Byblian preserved the original

in mnbt /manibt/(?) stele, instead of -h, as in lhm /alhm/ on them. For the

Phoenician mbt /maibt/(?). 3rd person sufxes of Phoenician, see Huehner-

Concerning vowels, along with the general gard (1991) and PPG3 (112).

Canaanite shift of (long) // > //, in Phoeni- In the nominal qatl, qitl, and qutl patterns

cian stressed (short) /a/ also developed into /o/ (segholate in Hebrew; Noun), Phoenician

(long?), as revealed by transcriptions such as did not insert, as does Tiberian Hebrew, an

white (cf. Hebrew l<<n) and anaptyptic vowel. bd servant, for exam-

he vowed (cf. Hebrew n<ar). ple, was transcribed into Greek as - (cf.

Contrary to Judahite Hebrew, diphthongs Hebrew ). Similarly, we know that

were regularly monophthongized in Phoenician mlk was pronounced /milk/ (cf. Hebrew

(see above), as in bt /bt/ house, temple ver- *malk > ml) (PPG3 81a, 193b; see

sus Hebrew bayi, and ll /ll/ night ver- also Fassberg 2002:210). By Late Punic, how-

sus Hebrew layl<. With some exceptions ever, there may have been a tendency to develop

in Byblos, intervocalic /h/ was regularly elided; anaptyxis, as illustrated by qbr tomb,

consequently, the system of the sufx pronouns probably /q(a)bar/ ( in this period was often

of the 3rd masculine and feminine singular dif- used to represent the vowel /a/).

fered from the Hebrew variants. After -u and Unlike Hebrew, Phoenician feminine singu-

-a (the original nominative and accusative case lar nominal sufx preserved the nal - -t in

ending), the sufxes -h and -h developed the absolute state, as in mlkt queen

into the vowels - and -, respectively, though /milkot/ (cf. Hebrew malk<). The form of

these vocalic sufx are not indicated in the the feminine singular sufx is thus /-ot/, based

Phoenician script, cf., e.g., ql his/her voice on the aforementioned stressed /a/ > /o/ shift

(though in Punic ql). Unlike in Hebrew, and the preservation of nal - -t. Such forms

after -i (the original genitive case ending) or occur in IH texts as well (note the feminine

a long vowel (dual/plural endings), these suf- singular verbs predicated to these subjects),

xes were written - -y and, in Late Punic, e.g., < m wisdom (Prov. 1.20, 9.1,

sometimes - -y, indicating a pronunciation 24.7), am wise woman (Judg.

/-iy/ and /-iy/, e.g., b-bty /bi-btiy/ < 5.29, Prov. 14.1); see also ma pil-

/*bi-bti-h/ in his temple; b-d dny lar (Ezek. 26.11) in a proclamation directed at

/bd adniy/ < /*bi-yad adni-h/ from her Tyre ( Addressee-Switching).

lord. In the dialect of Byblos (except Arm,

where intervocalic /h/ was still present), only 3. M o r p h o l o g y

the 3rd person feminine singular preserved the

original /h/, e.g., mdh /ammdh/ her For the independent personal pronoun of the

columns, while in the masculine, after -i or a 1st person singular, Phoenician/Punic had

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

phoenician/punic and hebrew 75

only the older form nk /ank/ and not, with prosthetic aleph (cf. Holmstedt 2007).

like Hebrew, the apparently more recent form This would then contrast with Hebrew

n. In Phoenician/Punic the distinction r, which is of nominal origin. However,

between the independent pronoun of the 3rd others have argued that Phoenician and

person masculine and feminine consisted of Hebrew r are cognate, with Phoeni-

a vowel alternation: /u/ for the masculine, /i/ cian attesting to an abbreviated form resulting

for the feminine, while the ending was /m/ for from grammaticalization (Huehnergard 2006).

both genders: masculine humat(u) and femi- Regardless, we may note that IH texts use the

nine himat(u), both written hmt. This is shorter form (without prosthetic aleph) - -,

contrary to Hebrew, which differentiates the e.g., the Song of Deborah (Judg. 5.7 [2x]) and

genders (in the 2nd and 3rd person plural) by the Gideon cycle (Judg. 6.17, 7.12, 8.26) (in

the consonants -- -m- and -- -n-, respectively, the rst three attestations actually - <-), both

while the vowel was (< *i) for both genders of which are geographically set in the north.

(masc. hmm< and fem. hnn<). The Instead of , Late Punic, in contrast to all

same difference between masculine and femi- other West Semitic languages, sometimes used

nine appears in the sufxed pronouns, Hebrew the interrogative/indenite pronoun my /m/

having the ending - -m for the masculine, who and m (Late Punic m) /m/ > /mu/

but - -n for the feminine, while Phoenician/ what, e.g., mnbt m

Punic has -/- -m/-nm for both genders, but bn ywrtn the stele which Yuratan built

a vowel opposition, namely // versus // (see (Jongeling 2008: 83).

above). To negate nouns and verbs, Phoenician/Punic

Contrary to Hebrew, the Phoenician/Punic used y // and bl /bal/ (along with the

causative was yipil instead of hif il, for exam- compound ybl /bal/), as opposed to

ple yqdt /yiqdit/ I consecrated; in Hebrew l. For a Hebrew example from

Punic and Late Punic the prex was written a prophet active in the north, see

- - or - y-. Two examples of the yif il -al-ymr li-l<<m and they do not

may occur in the Bible (Gordon 1951:50, 59): say in their hearts (Hos. 7.12). For prohibi-

ydat I informed (1 Sam. 21.3); tions, however, l was used, corresponding

yakkr<n he [Israel] recognizes us (not) (Isa. to Hebrew al.

63.16), though, admittedly, neither one of these

passages occurs in an Israelian context. 4. S y n t a x

The root of the verb go in Phoenician/Punic

is ylk (with initial yod, as also in Ugaritic), In syntax, Phoenician/Punic did not make use

in contrast to Hebrew hlk (with initial of the ancient preterite (prex conjugation)

he), though note that the prex-conjugation preceded by w- as a narrative tense (Hebrew

in Hebrew seems to be built on the root wayyiqol). Phoenician instead developed the

ylk. usage of the (absolute) innitive followed by

The passive participle probably had the pat- an independent personal pronoun for narra-

tern qal, as in Aramaic and against Hebrew tion, e.g., wkr nk ly

qal; cf. Late Punic bryk blessed and mlk r /wa-akor ank alaya milk ar/

the personal names transcribed in Latin as and I engaged against him the king of Assyria

Baricbal and Baric. (KAI 24.78; though for a different analysis

As relative/determinative marker, Old Byblian of such constructions see Lipiski 2010). Note

had z, corresponding to Hebrew z and instances of this usage in IH, e.g.,

z. The Hebrew forms occur in archaic poems, w-n< hak-kaddm and the vessels shat-

e.g., Judg. 5.5, Exod. 15.13, 16 (the former is tered (Judg. 7.19; albeit with a noun rather

also northern), but occasionally in IH texts as than a pronoun as subject), once more in the

well, e.g., << z yl<< your Gideon story.

father who bore you (Prov. 23:26).

Standard Phoenician/Punic used the relative/ 5. L e x i c o n

determinative marker . According to some

scholars, the form stems from an original Some lexical differences between Phoenician/

(supposedly connected with Akkadian a), Punic and Hebrew are worth noting. Phoenician

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

76 phoenician/punic and hebrew

uses kn /kn/ he was versus Hebrew Donner, Herbert, and Wolfgang Rllig. 19662002.

h<y<; pl /paal or paol/ he did, made Kanaanische und aramische Inschriften. 3 vols.:

versus Hebrew < < (Hebrew p<al is I5 2002, II2 1966, III2 1969. Wiesbaden: Harras-

sowitz (= KAI).

rare and poetic); r gold versus Hebrew Fassberg, Steven E. 2002. Why doesnt melex

z<h< (on Hebrew < r, see below); appear as ma:lex in pause in Tiberian Hebrew?

qrt city versus Hebrew r (on Hebrew (in Hebrew) Lonnu 64:207219.

Friedrich, Johannes, and Wolfgang Rllig. 1999.

qr, see below); yr month versus Phnizisch-punische Grammatik. 3rd edition, ed.

Hebrew (on Hebrew yra, see by Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo with cooperation

below); m men (based directly on singu- of Werner R. Mayer. Rome: Pontical Biblical

lar man) versus Hebrew n<m Institute (= PPG3).

Garbini, Giovanni. 1988. I dialetti del Fenicio. Il

(built from a different stem from the singular Semitico nordoccidentale. Studi di storia lingui-

form ). stica (Studi semitici N.S. 5), 5168. Rome: Univer-

Traces of such forms occur in the Bible, e.g., sit degli Studi La Sapienza.

< r gold appears four times in Prov- Garr, W. Randall. 1985. Dialect geography of Syria-

Palestine, 1000586 B.C.E. Philadelphia: Univer-

erbs and is used in Zech. 9.3 in a judgment sity of Pennsylvania Press.

directed against Tyre; qr city appears Gibson, John C. L. 1982. Textbook of Syrian Semitic

four times in Proverbs; and m men inscriptions. Vol. 3: Phoenician inscriptions includ-

occurs in Ps. 141.4 and Prov. 8.4. Finally, ing inscriptions in the mixed dialect of Arslan

Tash. Oxford: Clarendon.

note the presence of yra month in Ginsberg, H. L. 1970. The Northwest Semitic lan-

1 Kgs 6.3738, 8.2, along with the Phoenician guages. Patriarchs, ed. by Benjamin Mazar, 102

month names Ziv, Bul, and Etanim, suggesting 124, 293. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers

that Phoenician scribes are responsible for the University Press.

. 1982. The Israelian heritage of Judaism. New

Temple-building account, just as Phoenician York: Jewish Theological Seminary.

architects and craftsmen were responsible for Gordon, Cyrus H. 1951. Marginal notes on the

its actual construction. ancient Middle East. Jahrbuch fr Kleinasiatische

Forschung 2:5061.

Gratwick, A. S. 1971. Hannos Punic speech in the

References Poenulus of Plautus. Hermes 99:2545.

CIS = Corpus inscriptionum semiticarum. Gzella, Holger. Forthcoming. The linguistic position

IRT = Reynolds and Ward Perkins 1952. of Old Byblian. Lingustic studies in Phoenician

KAI = Donner and Rllig 19662002. grammar, ed. by Robert D. Holmstedt and Aaron

PPG3 = Friedrich and Rllig 1999. Schade. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

RS = Rpertoire dpigraphie smitique. Harris, Zellig S. 1936. A grammar of the Phoenician

language. New Haven, Connecticut: American

Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia. 1994. Lingua e Oriental Society.

scrittura a Biblo. Biblo. Una citt e la sua cul- Holmstedt, Robert D. The etymologies of Hebrew

tura, ed. by Enrico Acquaro, Federico Mazza, er and eC-. Journal of Near Eastern Studies

Sergio Ribichini, Gabriella Scandone, and Paolo 66:177191.

Xella, 179194. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Huehnergard, John. 1991. The development of

Ricerche. the third person sufxes in Phoenician. Maarav

. 1999. Quelques spcicits phonologiques du 7:183194.

punique tardif et la question de leur chronologie. . 2006. On the etymology of the Hebrew rela-

Numismatique, langues, critures et arts du livre, tive -. Biblical Hebrew in its Northwest Semitic

spcicit des arts gurs. Actes du VIIe col- setting: Typological and historical perspectives,

loque international sur lhistoire et larchologie ed. by Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz,

de lAfrique du Nord, Nice, 2131 octobre 1996, 103125. Jerusalem / Winona Lake, Indiana:

ed. by Serge Lancel, 183190. Paris: ditions du Magnes / Eisenbrauns.

comit des travaux historiques et scientiques. Jongeling, Karel. 2008. Handbook of Neo-Punic

. 2005. Les phases du phnicien: Phnicien inscriptions. Tbingen: Mohr Siebeck.

et punique. Proceedings of the 10th Meeting Kerr, Robert M. 2010. Latino-Punic epigraphy.

of Hamito-Semitic (Afroasiatic) Linguistics (Flor- Tbingen: Mohr Siebeck.

ence, 1820 April 2001), ed. by Pelio Fronzaroli Krahmalkov, Charles R. 2000. Phoenician-Punic dic-

and Paolo Marrassini, 95103. Florence: Diparti- tionary. Leuven: Peeters.

mento di Linguistica, Universit di Firenze. . 2001. Phoenician-Punic grammar. Leiden: Brill.

Avishur, Yitzhak. 2000. Phoenician inscriptions Lemaire, Andr. 20062007. La datation des rois

and the Bible. Tel-Aviv: Archaeological Center. de Byblos Abibaal et Elibaal et les relations entre

Blau, Joshua. 1982. On polyphony in Biblical lgypte et le Levant au Xe s. av. n... Acadmie

Hebrew. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Comptes rendus:

and Humanities. 16971716.

Corpus inscriptionum semiticarum. Pars prima.

1881 . Paris: E Reipublicae Typographeo (= CIS I).

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

phonetics of modern hebrew: acoustic 77

Lipiski, Edward. 2010. Le grondif en Phnicien. ence of Phonetics is divided into two areas of

Journal of Semitic Studies 55:110. speech investigation: the study of the physiol-

Masson, Olivier and Maurice Sznycer. 1972. Recher- ogy of speech production, articulatory phonet-

ches sur les Phniciens Chypre. Geneva / Paris:

Droz. ics; and the research of the acoustic output of

Peckham, J. Brian. 1968. The development of the speech, acoustic phonetics. Phonetics is related

Late Phoenician scripts. Cambridge, Massachu- to phonology, as both elds study speech sounds.

setts: Harvard University Press. However, phonetics is distinct from phonology

Rainey, Anson F. 2007. Redening HebrewA

Transjordanian language. Maarav 14:193203. in that it handles tangible properties of speech,

Rendsburg, Gary A. 1990. Linguistic evidence for while phonology focuses on the abstract prop-

the northern origin of selected psalms. Atlanta, erties of speech sounds, their organization and

Georgia: Scholars.

patterning cross-linguistically.

. 2002. Israelian Hebrew in the Book of Kings.

Bethesda, Maryland: CDL.

. 2003. A comprehensive guide to Israelian 2. H i s t o r y o f P h o n e t i c s

Hebrew: Grammar and lexicon. Orient 38:535.

Rpertoire dpigraphie smitique. 1900. Paris:

Imprimerie nationale (= RS).

Theories about speech production date back to

Reynolds, Joyce M. and John B. Ward Perkins. 1952. the 18th century; however, the investigation of

The inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania, in col- the acoustic output of speech began only in the

laboration with Salvatore Aurigemma, et al. Rome late 1930s, when machines such as the spectro-

/ London: British School at Rome (= IRT).

Rollston, Christopher A. 2008. The dating of the graph and cineradiographs became available.

early royal Byblian Phoenician inscriptions: A Acoustic phonetic research developed with the

response to Benjamin Sass. Maarav 15:5793. technological ability to record, measure and

Sass, Benjamin. 2005. The alphabet at the turn of the analyze speech.

millennium (Tel-Aviv. Occasional publications, 4).

Tel-Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Phonetic research in Modern Hebrew is

Archaeology. scarce, and much of the available phonetic

Segert, Stanislav. 1976. A grammar of Phoenician research is largely acoustic in nature (for few

and Punic. Munich: C. H. Beck. studies in articulatory phonetics see Articula-

Steiner, Richard C. 1982. Affricated ade in the

Semitic languages. New York: American Academy tory Phonetics). Several studies can be men-

for Jewish Research. tioned here: Chayen (1972, 1973), whose work

Sznycer, Maurice. 1967. Les passages puniques en was mostly descriptive in nature, recorded and

transcription latine dans le Poenulus de Plaute.

studied the Modern Hebrew accent of the

Paris: Klincksieck.

. 1999. Le punique en Afrique du Nord 1960s. Devens (1980) documented the speech

lpoque romaine daprs les tmoignages pi- of Oriental Hebrew speakers at the end of the

graphiques. Numismatique, langues, critures et 1970s and beginning of the 1980s. Enoch and

arts du livre, spcicit des arts gurs. Actes

du VIIe colloque international sur lhistoire et

Kaplan (1969) provided measurements regard-

larchologie de lAfrique du Nord, Nice, 2131 ing Modern Hebrew stress. Kreitman (2008)

octobre 1996, ed. by Serge Lancel, 171180. Paris: presented data of an acoustic phonetic study of

ditions du comit des travaux historiques et consonantal clusters in Modern Hebrew. Laufer

scientiques.

(1994, 1995, 1998) provides data regarding

Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo the acoustic nature of Modern Hebrew con-

(Sapienza Universit di Roma) sonants, particularly the nature of voicing in

Gary A. Rendsburg obstruents, while Laufer (1975, 1977) provides

(Rutgers University)

data regarding Modern Hebrew vowels. Lastly,

Aronson et al. (1996), Most, Amir and Tobin

(2000), Schwarzwald (1972) and Tene (1962)

Phonetics of Modern Hebrew: all provide acoustic measurements of vowels in

Acoustic Modern Hebrew.

1. I n t r o d u c t i o n t o A c o u s t i c 3. S p e e c h P r o d u c t i o n a n d

Phonetics Acoustic Output

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics which focuses Speech commences when air is expelled from

on the study of speech sounds from a concrete the lungs through the vocal tract and is released

physiological and physical perspective. The sci- into space. As a result, the air which exits the

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Mishnaic HebrewDocumento4 pagineMishnaic Hebrewdzimmer6Nessuna valutazione finora

- Languages From The World of The Bible: Holger GzellaDocumento37 pagineLanguages From The World of The Bible: Holger GzellaAhmed GhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- WILLEM SMELIK: The Languages of Roman PalestineDocumento21 pagineWILLEM SMELIK: The Languages of Roman PalestineLance LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- EHLL Transcription Into Greek and Latin ScriptDocumento22 pagineEHLL Transcription Into Greek and Latin Scriptivory2011Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jews and Godfearers at Aphrodisias: Greek Inscriptions with CommentaryDa EverandJews and Godfearers at Aphrodisias: Greek Inscriptions with CommentaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Temporal Clause-NiccacciDocumento5 pagineTemporal Clause-NiccacciJosé Estrada Hernández100% (2)

- Kaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFDocumento214 pagineKaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFoloma_jundaNessuna valutazione finora

- PAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical HebrewDocumento25 paginePAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical Hebrewivory2011Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFDocumento152 pagineNicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFphilologusNessuna valutazione finora

- Chicago Assyrian Dictionary Tomo 2 Letra A Parte DosDocumento552 pagineChicago Assyrian Dictionary Tomo 2 Letra A Parte DosJuan Alberto Salinas PortalNessuna valutazione finora

- Overview of Northwest Semitic languages and dialectsDocumento27 pagineOverview of Northwest Semitic languages and dialectsGerardo Lucchini100% (1)

- Priest in ExileDocumento17 paginePriest in Exilephilip shtern100% (1)

- Post-Biblical Hebrew Literature: Anthology of Medieval Jewish Texts & WritingsDa EverandPost-Biblical Hebrew Literature: Anthology of Medieval Jewish Texts & WritingsNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Semitic Studies-Vol. 1-2010 PDFDocumento334 pagineJournal of Semitic Studies-Vol. 1-2010 PDFeduardo alejandro arrieta disalvoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Old Aramaic Inscriptions From Sefire: (KAI 222-224) and Their Relevance For Biblical StudiesDocumento12 pagineThe Old Aramaic Inscriptions From Sefire: (KAI 222-224) and Their Relevance For Biblical StudiesJaroslav MudronNessuna valutazione finora

- Michalowski Sumerian in Woodard The Cambridge Encyclopedia of The World's Ancient LanguagesDocumento41 pagineMichalowski Sumerian in Woodard The Cambridge Encyclopedia of The World's Ancient Languagesruben100% (1)

- A Critique On The Methodology of Avi HurvitzDocumento12 pagineA Critique On The Methodology of Avi HurvitzPPablo LimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hittite King PrayerDocumento44 pagineHittite King PrayerAmadi Pierre100% (1)

- Grcki Jezicke Promene SpirantizationDocumento4 pagineGrcki Jezicke Promene SpirantizationshargaNessuna valutazione finora

- Story, History, and Theology in the Ancient Near EastDocumento28 pagineStory, History, and Theology in the Ancient Near Eastelias_11_85Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cuneiform Signs Flashcards 9-14 of Huehnergard's Akkadian GrammarDocumento2 pagineCuneiform Signs Flashcards 9-14 of Huehnergard's Akkadian Grammarspikeefix100% (1)

- Spirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdDocumento330 pagineSpirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdfcocajaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient Near Eastern Origins of an African KingdomDocumento24 pagineAncient Near Eastern Origins of an African KingdomDarius KD FrederickNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Linguistics 2010Documento51 pagineHistorical Linguistics 2010Si vis pacem...Nessuna valutazione finora

- Luzzatto, Goldammer. Grammar of The Biblical Chaldaic Language and The Talmud Babli Idioms. 1876.Documento144 pagineLuzzatto, Goldammer. Grammar of The Biblical Chaldaic Language and The Talmud Babli Idioms. 1876.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (2)

- Ancient Hebrew MorphologyDocumento22 pagineAncient Hebrew Morphologykamaur82100% (1)

- Gottingen LXX Sigla MVPDocumento2 pagineGottingen LXX Sigla MVPGeorge HartinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Temple of The Storm God in Aleppo Kay KohlmayerDocumento14 pagineThe Temple of The Storm God in Aleppo Kay KohlmayerAbd Aljalil ArabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Morag The Vocalization of Codex Reuchlinianus 1959Documento22 pagineMorag The Vocalization of Codex Reuchlinianus 1959adatan100% (2)

- Natan-Yulzary, Contrast and Meaning in The 'Aqhat StoryDocumento17 pagineNatan-Yulzary, Contrast and Meaning in The 'Aqhat StoryMoshe FeiferNessuna valutazione finora

- Biblical Hebrew and Ugaritic Grammar BibliographyDocumento152 pagineBiblical Hebrew and Ugaritic Grammar BibliographyHervis Francisco Fantini67% (3)

- The Verb Be' and Its Synonyms - John Verhaar Ruqaiya Hasan - 1972Documento241 pagineThe Verb Be' and Its Synonyms - John Verhaar Ruqaiya Hasan - 1972Tonka3cNessuna valutazione finora

- Y-Chromosomal Analysis of Greek Cypriots Reveals A Primarily Common Pre-Ottoman Paternal Ancestry With Turkish CypriotsDocumento16 pagineY-Chromosomal Analysis of Greek Cypriots Reveals A Primarily Common Pre-Ottoman Paternal Ancestry With Turkish Cypriotskostas09Nessuna valutazione finora

- Donald F. Murray Divine Prerogative and Royal Pretension Pragmatics, Poetics and Polemics in A Narrative Sequence About David 2 Samuel 5.17-7.29 JSOT Supplement Se PDFDocumento361 pagineDonald F. Murray Divine Prerogative and Royal Pretension Pragmatics, Poetics and Polemics in A Narrative Sequence About David 2 Samuel 5.17-7.29 JSOT Supplement Se PDFVeteris Testamenti LectorNessuna valutazione finora

- (OS 069) Spronk (Ed.) - The Present State of Old Testament Studies in The Low Countries PDFDocumento307 pagine(OS 069) Spronk (Ed.) - The Present State of Old Testament Studies in The Low Countries PDFOudtestamentischeStudienNessuna valutazione finora

- Itamar Singer PublicationsDocumento6 pagineItamar Singer PublicationsKeti KevanishviliNessuna valutazione finora

- Adiego (Hellenistic Karia)Documento68 pagineAdiego (Hellenistic Karia)Ignasi-Xavier Adiego LajaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramses III and The Sea Peoples - A Structural Analysis of The Medinet Habu InscriptionsDocumento33 pagineRamses III and The Sea Peoples - A Structural Analysis of The Medinet Habu InscriptionsScheit SonneNessuna valutazione finora

- Dura EuroposDocumento33 pagineDura Europosbogdan.neagota5423100% (1)

- Aage Westenholz, The Old Akkadian Period. History and Culture (V 2.0)Documento108 pagineAage Westenholz, The Old Akkadian Period. History and Culture (V 2.0)oscarsl100% (1)

- AKKADIAN LOANS IN EARLY ARABICDocumento15 pagineAKKADIAN LOANS IN EARLY ARABICsermediNessuna valutazione finora

- Vocabulario Semítico Occidental EmarDocumento148 pagineVocabulario Semítico Occidental EmarencarnichiNessuna valutazione finora

- Celtiberian ScriptDocumento3 pagineCeltiberian Scriptreddy_bhupatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Israel's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewDa EverandIsrael's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewNessuna valutazione finora

- Hoffner-Melchert Hittite PDFDocumento574 pagineHoffner-Melchert Hittite PDFjjlajomNessuna valutazione finora

- Nicholl. A Grammar of The Samaritan Language, With Extracts and Vocabulary. 1858?Documento152 pagineNicholl. A Grammar of The Samaritan Language, With Extracts and Vocabulary. 1858?Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNessuna valutazione finora

- Wright. The Chronicle of Joshua The Stylite: Composed in Syriac A.D. 507. 1882.Documento202 pagineWright. The Chronicle of Joshua The Stylite: Composed in Syriac A.D. 507. 1882.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Semitic Languages Outline Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta PDFDocumento754 pagineSemitic Languages Outline Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta PDFfabianhoks12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and HistoricityDocumento323 pagineBiblical Narratives, Archaeology and HistoricityMarcelo Martin MOSCANessuna valutazione finora

- Papyri and Ostraca From KaranisDocumento303 paginePapyri and Ostraca From KaranisPaula Veiga100% (3)

- Accents MasoreticDocumento16 pagineAccents MasoreticsikuningNessuna valutazione finora

- Old Avestan Syntax and Stylistics Martin L. West PDFDocumento196 pagineOld Avestan Syntax and Stylistics Martin L. West PDFNabhadr BijjayeshbaipoolvangshaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Bibliography of Ugaritic Grammar and Biblical Hebrew Grammar in The Twentieth CenturyDocumento76 pagineA Bibliography of Ugaritic Grammar and Biblical Hebrew Grammar in The Twentieth Centurye_biggs100% (1)

- Caminos Lettre Sennefer Baki JEADocumento12 pagineCaminos Lettre Sennefer Baki JEAValcenyNessuna valutazione finora

- Fisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptDocumento13 pagineFisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptGeez Bemesmer-LayNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanislav Segert, Rendering of Parallelistic Structures in The Targum Neofiti The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32,1-43)Documento18 pagineStanislav Segert, Rendering of Parallelistic Structures in The Targum Neofiti The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32,1-43)Bibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction to the New Testament: Reference EditionDa EverandIntroduction to the New Testament: Reference EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Article To Mr. Dugin PDFDocumento4 pagineArticle To Mr. Dugin PDFRodrigo MendesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Treatise On AntinomyDocumento13 pagineA Treatise On AntinomyRodrigo MendesNessuna valutazione finora

- Article To Mr. Dugin PDFDocumento4 pagineArticle To Mr. Dugin PDFRodrigo MendesNessuna valutazione finora

- Story of Hiroo OnodaDocumento5 pagineStory of Hiroo OnodaRodrigo MendesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pac Japanese BurmaDocumento15 paginePac Japanese BurmaRodrigo MendesNessuna valutazione finora

- Centering Prayer Guide: Rest in God Beyond ThoughtsDocumento6 pagineCentering Prayer Guide: Rest in God Beyond ThoughtsmgarcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Anthony Bloom. Orthodox PrayerDocumento4 pagineAnthony Bloom. Orthodox PrayerKelvin WilsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Praise and Worship Oct 10 2020Documento22 paginePraise and Worship Oct 10 2020CrisDBNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhagavad Gita Chapter SummariesDocumento33 pagineBhagavad Gita Chapter SummarieskalsridharNessuna valutazione finora

- Prophets of the Quran: (English - ي�ﻠ�إ)Documento7 pagineProphets of the Quran: (English - ي�ﻠ�إ)Sheri The FlashNessuna valutazione finora

- Fahrenheit 451 AnalyzationDocumento9 pagineFahrenheit 451 AnalyzationNubia Janell ClermontNessuna valutazione finora

- Hozier - Take Me To ChurchDocumento4 pagineHozier - Take Me To Churchmartinsfern3853Nessuna valutazione finora

- Invocation of BelialDocumento4 pagineInvocation of BelialYuri M75% (8)

- 5 6111565344961200434Documento206 pagine5 6111565344961200434Jedediah Phiri100% (8)

- SDA Quarter 2 - 2005Documento160 pagineSDA Quarter 2 - 2005Lino Jr AsmoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Lam Is One Letter of Greatest NameDocumento2 pagineLam Is One Letter of Greatest NamemubeenNessuna valutazione finora

- 32 Bible Verses About Being Born AgainDocumento4 pagine32 Bible Verses About Being Born AgainRoy Tanner100% (1)

- Altar Server ManualDocumento17 pagineAltar Server Manualapi-156016164Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Seal of God and Mark ofDocumento13 pagineThe Seal of God and Mark ofLloyd KauseniNessuna valutazione finora

- Grace Covenant: Presbyterian ChurchDocumento4 pagineGrace Covenant: Presbyterian ChurchGCPCAdminNessuna valutazione finora

- Stations BookletDocumento10 pagineStations Bookletandrewcyz96Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Bible Dilemma Historical Contradictions, Misquoted Statements, Failed Prophecies and Oddities in The Bible (PDFDrive)Documento529 pagineThe Bible Dilemma Historical Contradictions, Misquoted Statements, Failed Prophecies and Oddities in The Bible (PDFDrive)Dragan TodorićNessuna valutazione finora

- LoveDocumento43 pagineLoveLotos Barbot LBNessuna valutazione finora

- Job's Patience in SufferingDocumento37 pagineJob's Patience in SufferingALberto SOlanoNessuna valutazione finora

- HTTP - Spiritinfo - Blogspot.com - 2017 - 02 - What-Psalms-To-Use-In-Doing-Work - HTML-M 1 PDFDocumento85 pagineHTTP - Spiritinfo - Blogspot.com - 2017 - 02 - What-Psalms-To-Use-In-Doing-Work - HTML-M 1 PDFJentil TvNessuna valutazione finora

- Watchtower: Kingdom Ministry, 1985 IssuesDocumento68 pagineWatchtower: Kingdom Ministry, 1985 IssuessirjsslutNessuna valutazione finora

- Magazine Pulpit-2012-11 John MacArthurDocumento22 pagineMagazine Pulpit-2012-11 John MacArthurfortizmNessuna valutazione finora

- Joel Osteen - RebootingDocumento6 pagineJoel Osteen - RebootingMark PanchitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture The Dál Cais Version of The Battle of Clontarf and The Death of Irish Chivalry Clontarf Death of Western ChivalryDocumento42 pagineLecture The Dál Cais Version of The Battle of Clontarf and The Death of Irish Chivalry Clontarf Death of Western ChivalryscrobhdNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 5 For July 29, 2023Documento9 pagineLesson 5 For July 29, 2023Maria Rose AquinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Youth Arise - Session 3Documento1 paginaYouth Arise - Session 3Raffy RoncalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Herget Wayne Christine 1991 HaitiDocumento7 pagineHerget Wayne Christine 1991 Haitithe missions network100% (1)

- 2011 Sacred Choral PromoDocumento22 pagine2011 Sacred Choral PromocyhdzNessuna valutazione finora

- The Baptism of ChristDocumento6 pagineThe Baptism of ChristAngel FranciscoNessuna valutazione finora

- Facts About The Planet MoonDocumento5 pagineFacts About The Planet MoonfactsplanetmercuryNessuna valutazione finora