Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Near v. Minnesota

Caricato da

Noreenesse SantosCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Near v. Minnesota

Caricato da

Noreenesse SantosCopyright:

Formati disponibili

283 U.S.

697

Near v. Minnesota

June 1, 1931

Hughes, C.J.

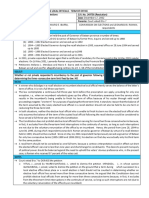

FACTS:

Jay Near published a scandal sheet in Minneapolis, in which he attacked local officials, charging that they were

implicated with gangsters. Minnesota officials obtained an injunction to prevent Near from publishing his

newspaper under a state law that allowed such action against periodicals. The law provided that any person

"engaged in the business" of regularly publishing or circulating an "obscene, lewd, and lascivious" or a

"malicious, scandalous and defamatory" newspaper or periodical was guilty of a nuisance, and could be enjoined

(stopped) from further committing or maintaining the nuisance.

ISSUE(s):

Whether or not the Minnesota "gag law" violate the free press provision of the First Amendment. YES

HELD:

Under the Free Press Clause of the First Amendment, and with limited exceptions, government may not

censor or prohibit a publication in advance.

The Supreme Court held that the statute authorizing the injunction was unconstitutional as applied. History

had shown that the protection against previous restraints was at the heart of the First Amendment. The

Court held that the statutory scheme constituted a prior restraint and hence was invalid under the First

Amendment. Thus the Court established as a constitutional principle the doctrine that, with some narrow

exceptions, the government could not censor or otherwise prohibit a publication in advance, even though

the communication might be punishable after publication in a criminal or other proceeding.

The Court held that prior restraint on publication (censoring newspapers in advance) in Minnesota was

the essence of censorship and the heart of what the First Amendment was designed to prevent. Even in

cases where printed statements could be punished after the fact (libelous statements, for example), neither

federal nor state governments could stop the publication of materials in advance. The Court cautioned that

prior restraint may be constitutional during wartime: No one would question but that a government might

prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or

the number and location of troops.

Commitment to freedom of the press means that individuals may publish (and other individuals may

encounter) ideas that are offensive, malicious, or even wrong. (Civil penalties apply for false statements

made knowingly and/or maliciously.) In the marketplace of ideas, citizens can choose between news

sources, rather than only those sources approved by government."

DOCTRINE(s)/KEY POINT(s):

- Liberty of the press is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment from invasion by state action.

- Liberty of the press is not an absolute right, and the State may punish its abuse.

- Cutting through mere details of procedure, the operation and effect of the statute is that public authorities

may bring a publisher before a judge upon a charge of conducting a business of publishing scandalous and

defamatory matter -- in particular, that the matter consists of charges against public officials of official

dereliction -- and, unless the publisher is able and disposed to satisfy the judge that the charges are true and

are published with good motives and for justifiable ends, his newspaper or periodical is suppressed and

further publication is made punishable as a contempt. This is the essence of censorship.

283 U.S. 697

-

Near v. Minnesota

June 1, 1931

A statute authorizing such proceedings in restraint of publication is inconsistent with the conception of the

liberty of the press as historically conceived and guaranteed.

The chief purpose of the guaranty is to prevent previous restraints upon publication. The libeler, however,

remains criminally and civilly responsible for his libels.

There are undoubtedly limitations upon the immunity from previous restraint of the press, but they are not

applicable in this case.

The liberty of the press has been especially cherished in this country as respects publications censuring

public officials and charging official misconduct.

Public officers find their remedies for false accusations in actions for redress and punishment under the

libel laws, and not in proceedings to restrain the publication of newspapers and periodicals.

The fact that the liberty of the press may be abused by miscreant purveyors of scandal does not make any

the less necessary the immunity from previous restraint in dealing with official misconduct.

Characterizing the publication of charges of official misconduct as a "business," and the business as a

nuisance, does not avoid the constitutional guaranty; nor does it matter that the periodical is largely or

chiefly devoted to such charges.

The guaranty against previous restraint extends to publications charging official derelictions that amount

to crimes.

Permitting the publisher to show in defense that the matter published is true and is published with good

motives and for justifiable ends does not justify the statute.

Nor can it be sustained as a measure for preserving the public peace and preventing assaults and crime.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Near V MinnesotaDocumento3 pagineNear V MinnesotaAlexir MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Near Vs MinnesotaDocumento2 pagineNear Vs MinnesotaGheeness Gerald Macadangdang MacaraigNessuna valutazione finora

- Near v Minnesota SCOTUS Freedom of Press Prior RestraintDocumento2 pagineNear v Minnesota SCOTUS Freedom of Press Prior RestraintGlenn Francis GacalNessuna valutazione finora

- Manotok v. NHA ruling on expropriation decreesDocumento1 paginaManotok v. NHA ruling on expropriation decreesMvv Villalon100% (2)

- (Case No. 420) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserDocumento2 pagine(Case No. 420) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserCecille MangaserNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court rules Board of Review has power to classify films but abused discretion in "Kapit sa PatalimDocumento2 pagineSupreme Court rules Board of Review has power to classify films but abused discretion in "Kapit sa PatalimMyra Myra75% (4)

- C. US vs. BALLARDDocumento2 pagineC. US vs. BALLARDShinji NishikawaNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs PerezDocumento2 paginePeople Vs PerezJessamine Orioque100% (1)

- Anonymous VDocumento5 pagineAnonymous VEnav LucuddaNessuna valutazione finora

- APOLONIO CABANSAG Vs GEMINIANA MARIA FERNANDEZ ET AL, G.R. No. L-8974, October 18, 1957Documento2 pagineAPOLONIO CABANSAG Vs GEMINIANA MARIA FERNANDEZ ET AL, G.R. No. L-8974, October 18, 1957Aguilar John Francis100% (1)

- De Knecht V BautistaDocumento1 paginaDe Knecht V BautistaAriel LunzagaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. SanchezDocumento1 paginaPeople v. SanchezivyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tilton Vs RichardsonDocumento2 pagineTilton Vs RichardsonRaymondNessuna valutazione finora

- New York Times v. USDocumento1 paginaNew York Times v. USNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. Court of Appeals Freedom of Expression, Libel and National SecurityDocumento2 pagineLopez vs. Court of Appeals Freedom of Expression, Libel and National SecurityRowardNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedman v. MarylandDocumento1 paginaFreedman v. MarylandNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Phil Columbian Assn v. Hon. Panis DigestDocumento2 paginePhil Columbian Assn v. Hon. Panis DigestErika Bianca Paras50% (2)

- Veroy vs. Layague WaiversDocumento2 pagineVeroy vs. Layague WaiversRowardNessuna valutazione finora

- Guidelines for Closing Broadcast StationsDocumento2 pagineGuidelines for Closing Broadcast StationsTrinca DiplomaNessuna valutazione finora

- CABANSAG vs. FERNANDEZDocumento7 pagineCABANSAG vs. FERNANDEZKristela AdraincemNessuna valutazione finora

- NPC v. ManalastasDocumento2 pagineNPC v. ManalastasKaren Joy MasapolNessuna valutazione finora

- US v. Ballard DigestDocumento1 paginaUS v. Ballard DigestAlthea M. SuerteNessuna valutazione finora

- Newsounds v. DyDocumento3 pagineNewsounds v. DyQueenie BoadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District Law Case WRITTEN BY: Allan G. OsborneDocumento1 paginaZobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District Law Case WRITTEN BY: Allan G. OsborneRagnar LothbrookNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Republic vs. Sandiganbayan (Sep Opinions)Documento2 pagine1 Republic vs. Sandiganbayan (Sep Opinions)Shannin MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- 604 House Building - Loan Assoc. V Blaisdell (Alfaro)Documento3 pagine604 House Building - Loan Assoc. V Blaisdell (Alfaro)Julius ManaloNessuna valutazione finora

- De Knecht v Bautista Eminent Domain RulingDocumento1 paginaDe Knecht v Bautista Eminent Domain RulingLester Nazarene Ople100% (1)

- Consti 2: Case Digests - Regado: Home Building & Loan Assn. V BlaisdellDocumento6 pagineConsti 2: Case Digests - Regado: Home Building & Loan Assn. V BlaisdellAleezah Gertrude RegadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Board of Education v. Allen Upholds Textbook Lending LawDocumento1 paginaBoard of Education v. Allen Upholds Textbook Lending LawLeft Hook OlekNessuna valutazione finora

- American Inter-Fashion Corp v. Office of The PresidentDocumento3 pagineAmerican Inter-Fashion Corp v. Office of The PresidentMaria Analyn100% (2)

- City of Manila v. Estrada Rodriguez C2020Documento3 pagineCity of Manila v. Estrada Rodriguez C2020Zoe Rodriguez100% (1)

- Lopez VS CaDocumento2 pagineLopez VS CaKeisha Mariah Catabay Lauigan100% (1)

- Gonzales Vs KatigbakDocumento2 pagineGonzales Vs KatigbakCourtney TirolNessuna valutazione finora

- Ayer Productions Vs CapulongDocumento2 pagineAyer Productions Vs CapulongLuiza CapangyarihanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ignacio v. ElaDocumento2 pagineIgnacio v. ElaChristopher Anniban SalipioNessuna valutazione finora

- Phil Journ Inc VS Thoenen Case DigestDocumento4 paginePhil Journ Inc VS Thoenen Case DigestIlyka Jean Sionzon100% (1)

- Balacuit v. CFIDocumento25 pagineBalacuit v. CFIellochocoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jose Vera V Jose Avelino: Preliminary InjunctionDocumento10 pagineJose Vera V Jose Avelino: Preliminary InjunctionTal MigallonNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest Corona V United Harbor Pilots AssociationDocumento3 pagineDigest Corona V United Harbor Pilots Associationm100% (2)

- In Re Ramon Tulfo Freedom of Expression, LibelDocumento2 pagineIn Re Ramon Tulfo Freedom of Expression, LibelRowardNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedom of Expression in PUVs and TerminalsDocumento4 pagineFreedom of Expression in PUVs and TerminalsEva TrinidadNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Freedman V MarylandDocumento2 pagine2 Freedman V MarylandKevin Juat BulotanoNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. PerezDocumento1 paginaPeople v. PerezNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Sumulong Vs GuerreroDocumento2 pagineSumulong Vs GuerreroJen DeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Subido v. OzaetaDocumento2 pagineSubido v. OzaetaEumir SongcuyaNessuna valutazione finora

- 39 Policarpio Vs Manila TimesDocumento2 pagine39 Policarpio Vs Manila TimesIvan LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Ayer Productions v. CapulongDocumento5 pagine4 Ayer Productions v. CapulongCedrick100% (1)

- PBMEO V PBMDocumento2 paginePBMEO V PBMG S100% (1)

- In Re JuradoDocumento3 pagineIn Re JuradoCamille Britanico100% (2)

- People v. Fajardo (GR No. L-12172 Aug 29, 1958)Documento2 paginePeople v. Fajardo (GR No. L-12172 Aug 29, 1958)Ei BinNessuna valutazione finora

- Manotok v. NHA-ClanorDocumento1 paginaManotok v. NHA-ClanorC.J. Evangelista100% (1)

- COMELEC Resolution Banning Campaign Materials in PUVs Violates Free Speech and Equal ProtectionDocumento6 pagineCOMELEC Resolution Banning Campaign Materials in PUVs Violates Free Speech and Equal ProtectionNoemi MejiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Malabanan vs. Ramento PDFDocumento2 pagineMalabanan vs. Ramento PDFKJPL_1987100% (1)

- Rosenbloom Vs MetromediaDocumento1 paginaRosenbloom Vs Metromediajane100% (1)

- American Inter Fashion v. OP PDFDocumento2 pagineAmerican Inter Fashion v. OP PDFAntonio RebosaNessuna valutazione finora

- PPL V Perez DigestDocumento2 paginePPL V Perez DigestJanine Oliva100% (1)

- People V ChavezDocumento2 paginePeople V ChavezTrisha Dela RosaNessuna valutazione finora

- UNESCO Official Sues Newspaper for DefamationDocumento1 paginaUNESCO Official Sues Newspaper for DefamationPrincess AyomaNessuna valutazione finora

- NEAR v MINNESOTA Supreme Court Establishes Prior Restraint BanDocumento3 pagineNEAR v MINNESOTA Supreme Court Establishes Prior Restraint BanAiram Crisna LimatogNessuna valutazione finora

- NEAR VS. MINNESOTA RULING PROTECTS PRESS FROM CENSORSHIPDocumento90 pagineNEAR VS. MINNESOTA RULING PROTECTS PRESS FROM CENSORSHIPLen Vicente - FerrerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Province of North Cotabato v. The Gov. of The Republic of The Phils. Peace PanelDocumento4 pagineThe Province of North Cotabato v. The Gov. of The Republic of The Phils. Peace PanelNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Why A Federalist Is Now An Anti-Federalist (Edmund S. Tayao)Documento2 pagineWhy A Federalist Is Now An Anti-Federalist (Edmund S. Tayao)Noreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Tano v. SocratesDocumento3 pagineTano v. SocratesNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Documento5 pagineSocial Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Tan v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento3 pagineTan v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Police Power OverreachDocumento3 paginePolice Power OverreachNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Two BBL Strategies (Artemio v. Panganiban)Documento2 pagineTwo BBL Strategies (Artemio v. Panganiban)Noreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Sema v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento4 pagineSema v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Rivera III v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento1 paginaRivera III v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Local Officials Eligible for Recall Election After Serving 3 TermsDocumento3 pagineLocal Officials Eligible for Recall Election After Serving 3 TermsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Benefits of Federalism and Parliamentary Government for the PhilippinesDocumento19 pagineBenefits of Federalism and Parliamentary Government for the PhilippinesfranzgabrielimperialNessuna valutazione finora

- Sangalang v. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocumento4 pagineSangalang v. Intermediate Appellate CourtNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Samson v. AguirreDocumento2 pagineSamson v. AguirreNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Talaga v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento3 pagineTalaga v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Sobejana-Condon v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento3 pagineSobejana-Condon v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Admin Law Creation ExemptionDocumento4 pagineAdmin Law Creation ExemptionNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Samahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan v. Quezon City PDFDocumento4 pagineSamahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan v. Quezon City PDFNoreenesse Santos100% (5)

- LGUS Eminent Domain PowersDocumento3 pagineLGUS Eminent Domain PowersNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Local Officials Term LimitsDocumento2 pagineLocal Officials Term LimitsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- MMDA Lacks Authority to Open Private RoadDocumento2 pagineMMDA Lacks Authority to Open Private RoadNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic v. RambuyongDocumento1 paginaRepublic v. RambuyongNoreenesse Santos100% (2)

- Disomangcop v. DatumanongDocumento3 pagineDisomangcop v. DatumanongNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Constitutional Framework For Economic Emergency - Expanding The Welfare State, Restricting The National Security (Raul C. Pangalangan)Documento16 paginePhilippine Constitutional Framework For Economic Emergency - Expanding The Welfare State, Restricting The National Security (Raul C. Pangalangan)Noreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Province of Batangas v. RomuloDocumento4 pagineProvince of Batangas v. RomuloNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Philippine Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Animals v. Commission On Audit, Et Al.Documento2 paginePhilippine Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Animals v. Commission On Audit, Et Al.Noreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Pimentel v. Aguirre, Et Al.Documento2 paginePimentel v. Aguirre, Et Al.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Kida v. Senate of The PhilippinesDocumento2 pagineKida v. Senate of The PhilippinesNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Mendoza v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento2 pagineMendoza v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Manila International Airport Authority v. Court of AppealsDocumento2 pagineManila International Airport Authority v. Court of AppealsNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Lucena Grand Central Terminal Inc. v. JAC Liner Inc.Documento2 pagineLucena Grand Central Terminal Inc. v. JAC Liner Inc.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Takings FlowchartDocumento1 paginaTakings FlowchartAmandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4Documento1 paginaConstitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4amberpenn70% (10)

- Right To Petition: Patrick Gryczka Rajiq Inam Jeffrey Karol DrozdzalDocumento7 pagineRight To Petition: Patrick Gryczka Rajiq Inam Jeffrey Karol DrozdzalYawningYogi KarolNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest (Macariola v. Asuncion)Documento1 paginaCase Digest (Macariola v. Asuncion)fina_ong6259Nessuna valutazione finora

- SWS V ComelecDocumento1 paginaSWS V ComelecnabingNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest - G.R. No. 15574 - Smith, Bell & Co. (LTD.) v. NatividadDocumento3 pagineCase Digest - G.R. No. 15574 - Smith, Bell & Co. (LTD.) v. NatividadJUPITER BARUELO100% (1)

- Constitutional Law Handout ModifiedDocumento56 pagineConstitutional Law Handout ModifiedJAIMENessuna valutazione finora

- 2017-01-17 Stewart Demand LetterDocumento5 pagine2017-01-17 Stewart Demand LetterGazetteonlineNessuna valutazione finora

- Commerce ClauseDocumento1 paginaCommerce ClauseBrat WurstNessuna valutazione finora

- Florida V JardinesDocumento2 pagineFlorida V JardinesCharisse Christianne Yu CabanlitNessuna valutazione finora

- Content Based Restriction of The Freedom of ExpressionDocumento2 pagineContent Based Restriction of The Freedom of ExpressionDodong LamelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II Outline-2Documento13 pagineCon Law II Outline-2Nija Anise BastfieldNessuna valutazione finora

- Lee Vs WeismanDocumento1 paginaLee Vs WeismanRaymondNessuna valutazione finora

- The Constitutional Right to ParentDocumento9 pagineThe Constitutional Right to ParentGary Krimson0% (1)

- Wallace V JaffreeDocumento11 pagineWallace V JaffreeGRAND LINE GMSNessuna valutazione finora

- Lemon VDocumento1 paginaLemon Vapi-405297138Nessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz No.4 - Ryan Paul Aquino - SN22-00258Documento2 pagineQuiz No.4 - Ryan Paul Aquino - SN22-00258RPSA CPANessuna valutazione finora

- Holt LetterDocumento2 pagineHolt LetterGazetteonlineNessuna valutazione finora

- Gitlow v. New YorkDocumento5 pagineGitlow v. New YorkAliNessuna valutazione finora

- Boyette v. Galvin, 412 F.3d 271, 1st Cir. (2005)Documento16 pagineBoyette v. Galvin, 412 F.3d 271, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Kirtland Local Schools FFRF LetterDocumento4 pagineKirtland Local Schools FFRF LetterWKYC.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Brettschneider - Con Law Spring 2020Documento8 pagineBrettschneider - Con Law Spring 2020Issa BestNessuna valutazione finora

- Hazelwood Vs KuhlmeierDocumento2 pagineHazelwood Vs Kuhlmeiergenn katherine gadunNessuna valutazione finora

- Processes of Constitutional Decisionmaking Cases and Materials ConnectedDocumento62 pagineProcesses of Constitutional Decisionmaking Cases and Materials Connectedvalerie.williams560100% (38)

- Columbus County Sheriffs Office NCReligious DisplayDocumento3 pagineColumbus County Sheriffs Office NCReligious DisplayMichael JamesNessuna valutazione finora

- Berger V City of SeattleDocumento1 paginaBerger V City of SeattlejimNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 2 - Course Syllabus: Inherent Powers of The State Police PowerDocumento7 pagineConstitutional Law 2 - Course Syllabus: Inherent Powers of The State Police PowerJESSIE DAUGNessuna valutazione finora

- Abrams Vs USDocumento3 pagineAbrams Vs USGheeness Gerald Macadangdang MacaraigNessuna valutazione finora

- White Light Corporation Et Al Vs City of Manila Etc 576 SCRA 416Documento2 pagineWhite Light Corporation Et Al Vs City of Manila Etc 576 SCRA 416Shannin MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 pagineAnnotated Bibliographyapi-397047794Nessuna valutazione finora