Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Outcome of End-Stage Renal Disease Patients

Caricato da

Muneeb SikanderCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Outcome of End-Stage Renal Disease Patients

Caricato da

Muneeb SikanderCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Outcome of End-Stage Renal Disease Patients

with Advanced Uremia and Acidemia

ABSTRACT

Iqbal Ur Rehman, Muhammad Khalid Idrees and Shoukat

Objective: To determine the outcome of End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) patients presenting with advanced uremia and

acidemia requiring hemodialysis and adverse events seen within 72 hours of admission.

Study Design: Cross-sectional study.

Place and Duration of Study: Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, Karachi, Pakistan, from October 2010 to

March 2011.

Methodology: ESRD patients with advanced uremia and acidemia were included in the study. History, physical

examination, complete blood count, serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes, arterial blood gases analysis, and ultrasound of

kidneys were done in each patient. Adverse events and outcome were recorded for the next 72 hours. Data was analyzed

by SPSS version (10). Mean value and standard deviation of quantitative measurements were calculated and statistical

significance computed by t-test. A p-value 0.05 was taken as significant. Statistical significance of categorical variables

was determined by chi-square test.

Results: Out of the 194 ESRD patients (mean age 46.54 14.07 years), 28 (14%) expired and 166 (86%) survived within

72 hours of admission. Hypotension requiring inotropic support was the commonest adverse event observed in 40 (20.6%)

cases followed by fits in 31 (16%); and 25 (12.9%) patients required ventilatory support. Mortality was high in patients

above 50 years of age. There was no statistically significant difference between two genders regarding adverse events

and mortality.

Conclusion: The morbidity and mortality of patients with ESRD are serious concerns. Early referral of patients with ESRD,

before they develop severe acidosis, can prevent significant morbidity and mortality.

Key Words: Uremia. Acidosis. Dialysis. Inotropic. Mortality. Renal failure.

INTRODUCTION

The global burden of End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

is rapidly rising and increasing number of patients is

entering in the pool of those on renal replacement

therapy (dialysis or transplant). Approximately 1.9 million

ESRD patients are undergoing hemodialysis worldwide.

Access to the facility of Renal Replacement Therapy

(RRT) correlates directly with socioeconomic development and regional income.1 The initiation of RRT in

developing world is restricted to fewer than a quarter of

ESRD patients.1 In 2010, only 58.9% of ESRD patients

received dialysis or had kidney transplantation. There

was disparity among different parts of the world

regarding access to renal replacement therapy, ranging

from less than 2% in most of sub-Saharan Africa to over

70% in high-income North America, high-income Asia

Pacific, and East Asia.2 The annual incidence of EndStage Renal Disease (ESRD) in Pakistan is estimated at

about 100 per million populations,3 and it is increasing

Department of Nephrology, Sindh Institute of Urology and

Transplantation (SIUT), Karachi.

Correspondence: Dr. Iqbal Ur Rehman, Department of

Nephrology, SIUT, Dewan Farooq Medical Complex,

Off M.A. Jinnah Road, Karachi.

E-mail: siutpakistan@gmail.com

Received: July 18, 2014; Accepted: October 16, 2015.

with each passing year. Only 10% of renal failure patients

receive renal replacement therapy.4

ESRD patients have a high mortality rate during the first

year of initiation of dialysis and at least 6% patients die

within first 90 days.5 Late nephrology referral has been

associated with adverse outcomes among ESRD

patients. In Pakistan, till few years ago, almost 100%

patients presented in emergency department with

uremia and required urgent dialysis.6 A recent survey

from Karachi (the largest metropolis of Pakistan) found

that 41% of family physicians did not know when to refer

a renal failure patient to nephrologist.7

In late referral patients with ESRD, metabolic acidosis is

present which is in most cases mild and partially or fully

compensated with pH > 7.2 and may not be life

threatening. However, more severe acidosis i.e. pH

< 7.2 can cause hemodynamic instability (hypotension,

cardiac arrhythmias),8 especially in patients with

advanced uremia. Metabolic acidosis, however, is not

the sole culprit for early mortality and morbidity whereas

other factors may also contribute.9 During the first year

of dialysis, mortality is lowest during the first month and

at peak during the second and third month.10 Analysis of

patients record from the authors institution revealed that

patients were received with advanced uremia and

metabolic acidosis requiring urgent hemodialysis via

temporary vascular access and frequently need

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2016, Vol. 26 (1): 31-35

31

Iqbal Ur Rehman, Muhammad Khalid Idrees and Shoukat

ventilatory and inotropic support with high (very early,

within 72 hours) mortality. As this type of presentation is

now rare in developed and Western countries, this

phenomenon is not reported in the literature and its

prognostic factors are not well studied.

There is lack of data regarding the outcome of patients

with advanced uremia and acidemia in our population.

This study was conducted to study the patients

demographics, occurrence of adverse events (fits,

hypotension requiring inotropic support and requirement

of ventilatory support) and their impact on outcome

(survival/expiry) of the patients who presented with

advanced uremia and acidemia.

METHODOLOGY

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Sindh

Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT), Karachi,

Pakistan, from October 2010 to March 2011. Patients

between 15 - 60 years of age, presenting first time to

emergency department of SIUT having advanced

uremia (arbitrarily defined as serum urea level 250

mg/dl at first presentation at SIUT) and diagnosed ESRD

on the basis of clinical features, serum biochemistry and

ultrasound kidneys, were included in the study by

convenience sampling technique. Patients with acute or

chronic renal failure and those already on dialysis were

excluded from the study. The study was approved by the

Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of the institution.

Informed consent was obtained.

History was taken and physical examination done. Blood

samples for Complete Blood Count (CBC) and serum

biochemistry (serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes) sent

along with a separate heparinized sample of arterial

blood for pH, PO2, PCO2, O2 saturation and bicarbonate

measurement. Ultrasound of kidneys was done to see

the size of the kidneys and exclude obstruction.

Outcome of patients (whether the patient expired or

survived) was observed for the next 72 hours after

admission. Additionally, adverse events (fits, need of

mechanical ventilation and hypotension) were observed.

During this period, hemodialysis was done in supervision

of trained physician. The dialysis was of short duration

(90 - 120 minutes), with low flux hollow fibre

(polysulphone) dialyzer, without any anticoagulation

(saline flushes to prevent clotting of dialyzer),

bicarbonate dialysate, blood flow of 250 ml/minute and

dialysate flow of 500 ml/minute. Ultrafiltration was done

in patients having fluid overload. All the relevant

information (survival, death and adverse outcome) were

recorded on the proforma.

Data was entered and analyzed in statistical software

(SPSS version 10). Frequency and percentage were

computed for categorical (qualitative) variables like age

group, gender, outcome of end stage of renal disease

patients and adverse event. Mean and standard

deviation were computed for quantitative measurement

like age, temperature, hemoglobin, TLC, platelet,

32

potassium, sodium and pH. Statistical significance of

these variables was determined by t-test and value of p

equal or less than 0.05 was taken as statistically

significant. Similarly, the statistical significance of

categorical data was determined by chi-square test.

Stratification was done with regard to age, gender and

number of dialysis to observe the effect on outcomes.

RESULTS

This study included 194 ESRD patients (130 males and

64 females) having advanced uremia and acidemia. The

average age of the patients was 46.54 14.07 years and

most of the patients were above 50 years of age.

Patients who expired were older as compared to those

who survived (52.29 12.77 vs. 45.57 14.09 years) and

this difference was statistically significant (p= 0.019). All

the patients had fairly advanced uremia with a mean

serum urea of 349.04 77.6 mg/dl and mean serum

creatinine of 14.44 4.41 mg/dl respectively. About 40%

patients had hyperkalemia. The patients who expired

had lower pH (7.01 0.11) as compared to those who

survived (7.14 0.09) and this difference was statistically

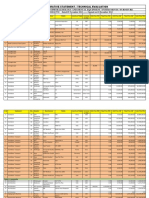

significant (p=0.0005). Table I shows the descriptive

statistics of study variables.

Table I: Descriptive statistics of study variables (n=194).

Variables

Mean SD

Max - Min

98.59 0.96

103 - 98

88.06 20.51

122 - 47

Platelet

246.78 139.95

716 - 5

Sodium

134.66 8.48

168 - 107

H.ion (nmol/L)

79.15 21.94

Creatinine mg/dL

14.44 4.41

Age (years)

Temperature*

Hemoglobin

Mean arterial pressure

TLC

Potassium**

pH

Urea mg/dl

46.54 14.07

7.87 1.82

15.48 8.23

5.41 1.35

65 - 15

11 - 3

56 - 1

9-2

7.12 0.13

7.29 - 6.84

349.04 77.6

594 - 251

*Out of 194 patients, 66 (34%) had temperature more than 100F

** Out of 194 patients, 78 (40.2%) had hyperkalemia

144 - 52

36.9 - 8.0

Hypotension requiring inotropic (vasopressor) support

was the commonest adverse event that was observed in

40 (20.6%) patients followed by fits (seizures) in 31

(16%) patients while 25 (12.9%) patients required

ventilatory support. Fits and ventilatory support were

more common in patients below 30 years of age while

hypotension was observed in patients above 50 years of

age. Frequency of fits and ventilatory support was nearly

same in male and female (p=0.46 and p=0.90,

respectively) while hypotension was more common in

females than males (28.1% vs. 16.9%); but this

difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.07).

Frequency of hypotension and ventilatory support was

high in those cases who had only one session of dialysis

as compared to those who required 2 and 3 dialysis

sessions during the period of 72 hours (p=0.001 and

0.0001 respectively) while there was no statistically

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2016, Vol. 26 (1): 31-35

Outcome of ESRD with advanced uremia and acidemia

significant difference in case of fits (p=0.172). These

patients had more severe metabolic acidosis and

consequent highest mortality as shown in Table II.

Dialysis prescription varied very little from patient to

patient as all the patients had short duration dialysis and

dialysate flow (500 ml/minute) whereas dialysate

compositions (prepared in the institution in bulk) were

fixed and dialyzer used was of the same size (1.4 m2) for

all the patients.

Fourteen percent (28/194) patients expired and 86%

(166/194) survived within 72 hours after admission.

Mortality/expiry rate was highest (20.8%) among those

above 50 years of age while it was about 8% (8 out of

98) in those below 50 years of age. Mortality was

statistically significantly higher in those above 50 years

of age as compared to those below 50 years (p=0.029).

There was no difference in both genders regarding

mortality (p=0.918). Similarly, mortality/expiry rate was

100% in those cases who had only one dialysis session.

Frequencies of adverse events and mortality are

summarized in Table III.

Table II: Comparison of characteristics between survived and expired

patients.

Variables

Survive group

Expired group

p-value

111 (66.9%)

19 (67.9%)

0.918

45.57 14.09

52.29 12.77

99.16 1.60

0.001*

(mmHg)

91.62 18.25

66.94 20.71

0.0005*

TLC (1000/mm3)

14.63 7.39

20.46 11

0.0005*

376.64 92.67

0.042

5.89 2.03

0.002*

Gender

Male

Female

Age (years)

Temperature (F)

Mean arterial pressure

Hemoglobin (gm/dl)

Platelets (100,000/mm3)

Urea (mg/dl)

Creatinine (mg/dl)

Bicarbonate (mmol/L)

PCO2

(n=166)

55 (33.1%)

98.49 0.78

7.88 1.83

(n=28)

09 (32.1%)

7.76 1.79

247.21 136.7

244.25 147.68

14.45 4.51

14.04 4.07

344.39 74.09

7.62 2.85

14.86 5.31

0.0005*

H ion (nmol/L)

75.32 19.15

101.82 23.98

Fits

Hypotension

Ventilatory support

* Significant

21 (12.7%)

21 (12.7%)

10 (6%)

Table III: Adverse events and mortality.

Age groups

30 years

31 to 50 years

> 50 years

0.649

7.01 0.11

134.18 8.54

Adverse event

0.917

0.0005*

134.76 8.49

7.14 0.09

0.734

21.93 13.82

Sodium (mEq/L)

pH

0.019

10 (35.7%)

19 (67.9%)

15 (53.6%)

Number

36

62

0.74

0.0005*

0.002*

0.0001*

0.0001*

DISCUSSION

The authors specifically studied outcome of uremic

patients who were acidotic and in need of emergency

dialysis, which is a common scenario in Pakistan due to

late diagnosis or referral. Most of those patients, who

have an uneventful course within few days after starting

dialysis, usually do well subsequently. The total number

of patients with a span of 6 months, suggests that this is

still a frequent mode of presentation in Pakistan. The

average age of these patients (46.54 14.07 years) is

much less than that reported from USA11 but close to

that in other South Asian countries.12 The number of

males was almost twice that of females in this study.

This is contrary to the finding from community based

study from Karachi13 which did not find gender

difference in occurrence of kidney disease among

general population. The lesser number of females in this

study is probably due to gender bias and social

deprivation of females.

This study included patients with severe acidosis i.e.

pH < 7.3. The patients who eventfully expired had more

severe acidemia compared to those who survived.

Acidosis of such severity may lead to adverse

hemodynamic effects such as arteriolar dilatation and

depression of myocardial contractility.8 In an

experimental study, the effect of metabolic acidosis

induced by infusion of hydrochloric acid in pigs was

studied which showed that lowering of pH to 7.1 resulted

in diminished cardiac contractility and increased the

ventricular stroke work per minute.14 Numerous studies

on patients with lactic acidosis in critical care setting

have highlighted the adverse effects of profound

acidemia.15 The authors were unable to find any study

where effect of such profound metabolic acidosis in

uremic patients has been studied.

It is difficult to compare these patients (whose acidosis

is rapidly corrected by dialysis) with non-uremic patients

with lactic acidosis. More than 40% patients had

hyperkalemia but it had no effect on mortality. It is

probably because of the rapid removal of potassium in

process of hemodialysis. Patients who expired had

higher temperature and higher TLC as compared to

those who survived. This could be due to presence of

some unrecognized infection (such as UTI) or result

from systemic inflammation due to metabolic acidosis.

Patients with higher PCO2 (respiratory acidosis) had

Fits

7 (19.5%)

11 (17.8%)

Hypotension

6 (16.7%)

7 (11.3%)

Ventilatory support

Expired

5 (13.8%)

3 (8.3%)

7 (11.3%)

5 (8.1%)

96

13 (13.5%)

27 (28.1%)

13 (13.5%)

20 (20.8%)

Males

130

19 (14.6%)

22 (16.9%)

17 (13.1%)

19 (14.6%)

Total

31 (16%)

40 (20.6%)

25 (12.9%)

28 (14%)

Number of adverse events

Females

64

12 (18.8%)

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2016, Vol. 26 (1): 31-35

18 (28.1%)

8 (12.5%)

9 (14.1%)

33

Iqbal Ur Rehman, Muhammad Khalid Idrees and Shoukat

higher mortality. Patients with pure metabolic acidosis

have lower PCO2 due to respiratory compensation but

exhaustion of respiratory muscles leads to concomitant

respiratory acidosis (more pronounced among diabetic

CKD patients) and consequent higher morbidity and

mortality.16

Hypotension was the commonest adverse event

observed in 20.6% cases followed by fits (16%) and

12.9% patients required ventilator support. High

mortality rate (60%) observed in patients who were on

ventilator followed by hypotension (47.5%) and fits

(2.3%). Seizures are not uncommon in patients with

advanced uremia on presentation and are multi-factorial

in causation. Seizures in uremic patients can be a

manifestation of uremia, metabolic derangements or the

treatment of these derangements.17 Bergen and

colleagues reported the incidence of seizures (fits) of

approximately 10% in patients with chronic renal

failure.18 The lower frequency of seizures among our

study participants may be due to short period of

observation (72 hours).

Mechanical ventilation was required in 12.9% patients

which is less than 26% as reported by Rocha19 among

maintenance dialysis patients admitted in ICU. Patients

with advanced uremia often have pulmonary edema,

inability to clear upper airways and exhaustion due to

respiratory muscle fatigue. Similarly, 20.6% of our

patients had hypotension and required inotropic support

compared to 24% as reported by Rocha.19 The

difference in the two study populations is that there was

high proportion of patients with sepsis in the study of

Rocha while these patients had severe metabolic

acidosis.

The outcome of ESRD patients with advanced uremia

was quite dismal in this study. Fourteen percent patients

expired within 72 hours of admission. This is much

higher than the 6% mortality during first 90 days of start

of dialysis in USA.5 In Canada,20 early 90-day mortality

after initiation of dialysis was upto 34.7% of one year

mortality. However, there is wide variation in patient

mortality in different parts of the world. DOPPS found

that one-year mortality rates were 6.6% in Japan, 15.6%

in Europe and 21.7% in the USA and variability in

demographic and co-morbid conditions at inception of

dialysis could explain only part of the differences in

mortality rate between these countries.21 It has been

observed that both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality risk factors are equally

increased among dialysis patients and should be

focused.22

In this study, frequency of expired patients was high in

above 50 years of age. This is well known phenomenon

that mortality increases with increasing age.20 Mortality

rate was similar in male and female patients in this study.

Gender difference has been reported in the survival of

34

new ESRD patients. Bloembergen et al. found that

males receiving chronic dialysis had a 22% higher

mortality than females, mostly because of excess risk of

acute myocardial infarction and malignancies.23

However, another study from European cohort showed

that young and diabetic women starting dialysis had

higher non-cardiovascular mortality risk than men while

females of 45 years old and above had lower

cardiovascular mortality than men.24 The authors did not

find such gender difference in this study. This may be

because of smaller number of females. Higher

frequency of hypotension, need of ventilatory support

and 100% mortality among patients, who survived to

have only one dialysis session, reflects that these

patients were more seriously sick. The dialysis

prescription was more or less the same among all the

patients and it is not possible to judge the effect of

dialysis on survival or mortality in this small single centre

study.

This study is, to the best of authors' knowledge, the first

of its kind from this part of the world which highlights the

high mortality rate among ESRD patients presenting

with advanced uremia and metabolic acidosis/acidemia

during first 72 hours of admission. It highlights the

importance of accurate reporting of events during initial

days of start of dialysis. Early referral to nephrologist

and attendance of pre-dialysis clinics may facilitate the

avoidance of central venous catheters, timely creation of

AV fistula, correction of anemia, mineral bone

metabolism and malnutrition, which ultimately improve

survival on dialysis.25

It is a single center study and observation period was

only 3 days, so co-morbid conditions other than ESRD

could affect the outcome and adverse events.

CONCLUSION

The morbidity and mortality of patients with ESRD are

serious concerns for patients presenting late with

advanced uremia and severe metabolic acidosis. Early

referral of patients, with ESRD before they develop

severe acidosis, will prevent significant morbidity and

mortality.

REFERENCES

1. Anand S, Bitton A, Gaziano T. The gap between estimated

incidence of end-stage renal disease and use of therapy. PLoS

ONE 2013; 8:e72860. Available at: http://www.plosone.org/

article/fetchObject.action?uri=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjou

rnal.pone.0072860&representation=PDF. Accessed on April

18, 2014.

2. Wulf SK, Naghavi M. End-stage renal disease: unmet

treatment needs across the globe. Lancet 2013; 381:S150.

3. Rizvi SA, Naqvi SAA. Renal replacement therapy in Pakistan.

Saudi J Kid Dis Transpl 1996; 7:404-8.

4. Wasti AZ, Fatima N, Ashiq A, Khalid E. Cardio-renal profiling

with hs-CRP and its implications as a diagnostic tool in chronic

kidney disease patients. Int Sci Invest J 2013; 2:1-6.

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2016, Vol. 26 (1): 31-35

Outcome of ESRD with advanced uremia and acidemia

5. Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Early death in dialysis patients: risk

factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc

Nephrol 1996; 7:2169-75.

6. Anees M, Mumtaz A, Nazir M, Ibrahim M, Rizwan SM, Kausar

T. Referral pattern of hemodialysis patients to nephrologists.

J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2007; 17:671-4.

7. Yaqub S, Kashif W, Raza MQ, Aaqil H, Shahab A, Chaudhary

MA, et al. General practitioners' knowledge and approach to

chronic kidney disease in Karachi, Pakistan. Indian J Nephrol

2013; 23:184-90.

8. Kraut JA, Madias NE. Metabolic acidosis: pathophysiology,

diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6:274-85.

9. Movilli E, Bossini N, Viola BF, Camerini C, Cancarini GC, Feller P,

et al. Evidence for an independent role of metabolic acidosis

on nutritional status in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial

Transplant 1998; 13:674-8.

10. Collins AJ, Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Chen SC. The state of

chronic kidney disease, ESRD, and morbidity and mortality in

the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4:S5-11.

11. Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Early death in dialysis patients: risk

factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc

Nephrol 1996; 7:2169-75.

12. Modi GK, Jha V. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in

India: a population-based study. Kidney Int 2006; 70:2131-3.

13. Alam A, Amanullah F, Baig-Ansari N, Lotia-Farrukh I, Khan FS.

Prevalence and risk factors of kidney disease in urban Karachi:

baseline findings from a community cohort study. BMC Res

Notes 2014; 7:179.

14. Stengl M, Ledvinova L, Chvojka J, Benes J, Jarkovska D,

Holas J, et al. Effects of clinically relevant acute hypercapnic

and metabolic acidosis on the cardiovascular system: an

experimental porcine study. Crit Care 2013; 17:R303.

15. Kimmoun A, Novy E, Auchet T, Ducrocq N, Levy B.

Hemodynamic consequences of severe lactic acidosis in

shock states: from bench to bedside. Crit Care 2015; 19:175.

16. Ikegaya N, Yonemura K, Suzuki T, Kato-Ohishi H, Taminato T,

Hishida A. Impairment of ventilatory response to metabolic

acidosis in insulin-dependent diabetic patients with advanced

nephropathy. Ren Fail 1999; 21:495-8.

17. de Lacerda GCB. Treating seizures in renal and hepatic failure.

J Epilepsy Clin Neurophysiol 2008; 14:46-50.

18. Bergen DC, Ristanovic R, Gorelick PB, Kathipalia S. Seizures

and renal failures. Int J Artif Organs 1994; 17:247-51.

19. Rocha E, Soares M, Valente C, Nogueira L, Jr HB, Godinho M,

et al. outcomes of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury

and end-stage renal disease requiring renal replacement

therapy: a case control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;

24:1925-30.

20. McQuillan R, Trpeski L, Fenton S, Lok CE. Modifiable risk

factors for early mortality on hemodialysis. Int J Nephrol 2012;

2012:435736.

21. Goodkin DA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Koenig KG, Wolfe RA, Akiba T,

Andreucci VE, et al. Association of comorbid conditions and

mortality in hemodialysis patients in Europe, Japan, and the

United States: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns

Study (DOPPS). J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14:3270-7.

22. de Jager DJ, Grootendorst DC, Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Tomas

LM, Ansell D, et al. Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular

mortality among patients starting dialysis. JAMA 2009; 302:

1782-9.

23. Bloembergen W, Port FK, Mauger EA, Wolfe RA. Causes of

death in dialysis patients: racial and gender differences. J Am

Soc Nephrol 1994; 5:1231-42.

24. Carrero JJ, de Jager DJ, Verduijn M, Ravani P, De Meester J,

Heaf JG, et al. Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular

mortality among men and women starting dialysis. Clin J Am

Soc Nephrol 2011; 6:1722-30.

25. Garcia-Garcia G, Briseo-Rentera G, Luqun-Arellan VH, Gao Z,

Gill J, Tonelli M. Survival among patients with kidney failure in

Jalisco, Mexico. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:1922-7.

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2016, Vol. 26 (1): 31-35

35

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Handcuffs For The Guilty - Media Capture and Government AccountabilityDocumento20 pagineHandcuffs For The Guilty - Media Capture and Government AccountabilityMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Cost Analysis of Tumor Downsizing For Hepatocellular Carcinoma IndiaDocumento3 pagineCost Analysis of Tumor Downsizing For Hepatocellular Carcinoma IndiaMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 2002 The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness Theory and Evidence From India PDFDocumento38 pagine2002 The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness Theory and Evidence From India PDFMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 - Referrals Peer Screening and Enforcement in Consumer CreditDocumento31 pagine2015 - Referrals Peer Screening and Enforcement in Consumer CreditMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Short Term Donor Outcomes After HepatectomyDocumento5 pagineShort Term Donor Outcomes After HepatectomyMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparitive Statement T121210DHUS-20130213Documento29 pagineComparitive Statement T121210DHUS-20130213Muneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Nature - Comparison of Apollolian and Dionysian DualitiesDocumento52 pagineHuman Nature - Comparison of Apollolian and Dionysian DualitiesMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 - Underinvestment in A Profitable Technology - Seasonal Migration in BangladeshDocumento79 pagine2014 - Underinvestment in A Profitable Technology - Seasonal Migration in BangladeshMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 1982 Gecas - The Self-Concept. Conceptul de Autoeficacitate. Autoeficacitatea PerceputaDocumento34 pagine1982 Gecas - The Self-Concept. Conceptul de Autoeficacitate. Autoeficacitatea PerceputavoicekNessuna valutazione finora

- Roland Berger Tab How To Do Business in Iran 20151125Documento12 pagineRoland Berger Tab How To Do Business in Iran 20151125Muneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 1949 Heidegger - The Question Concerning Technology, and Other EssaysDocumento222 pagine1949 Heidegger - The Question Concerning Technology, and Other EssaysJope Guevara100% (5)

- Textbook: Readings:: Cubs MSC Finance 1999-2000 Asset Management: Lecture 3Documento13 pagineTextbook: Readings:: Cubs MSC Finance 1999-2000 Asset Management: Lecture 3Atif SaeedNessuna valutazione finora

- ChangeManagement EN PDFDocumento32 pagineChangeManagement EN PDFMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Genotype Distribution in Pakistan Comprehensive Review of Recent DataDocumento19 pagine2016 Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Genotype Distribution in Pakistan Comprehensive Review of Recent DataMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Are We Ready For A New Epidemic of Under Recognized Liver Disease in South AsiaDocumento5 pagineAre We Ready For A New Epidemic of Under Recognized Liver Disease in South AsiaMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma in PakistanDocumento2 pagineHepatocellular Carcinoma in PakistanMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Math May 2008 MS C3Documento9 pagineMath May 2008 MS C3dylandonNessuna valutazione finora

- LBO DCF ModelDocumento38 pagineLBO DCF ModelMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Import Substitution Industrialization in Latin AmericaDocumento29 pagineImport Substitution Industrialization in Latin AmericaMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Edexcel GCE: Core Mathematics C2Documento20 pagineEdexcel GCE: Core Mathematics C2Muneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Dashboard Reporting TemplateDocumento8 pagineDashboard Reporting TemplateMuneeb SikanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Math May 2008 MS C2Documento10 pagineMath May 2008 MS C2dylandonNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Atty. Represented Conflicting Interests in Property CaseDocumento35 pagineAtty. Represented Conflicting Interests in Property CaseStella C. AtienzaNessuna valutazione finora

- All Glory Book-1Documento187 pagineAll Glory Book-1fredkayf100% (1)

- Application for Test Engineer PositionDocumento3 pagineApplication for Test Engineer PositionAsz WaNieNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 8Documento2 pagineUnit 8The Four QueensNessuna valutazione finora

- Flowera, Fruits and SeedsDocumento66 pagineFlowera, Fruits and SeedsNikkaMontil100% (1)

- Year 9 Autumn 1 2018Documento55 pagineYear 9 Autumn 1 2018andyedwards73Nessuna valutazione finora

- Life Cycle of A BirdDocumento3 pagineLife Cycle of A BirdMary Grace YañezNessuna valutazione finora

- Description Text About Cathedral Church Jakarta Brian Evan X MIPA 2Documento2 pagineDescription Text About Cathedral Church Jakarta Brian Evan X MIPA 2Brian KristantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Nokia CaseDocumento28 pagineNokia CaseErykah Faith PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Teaching ResumeDocumento2 pagineProfessional Teaching Resumeapi-535361896Nessuna valutazione finora

- English 7 1st Lesson Plan For 2nd QuarterDocumento4 pagineEnglish 7 1st Lesson Plan For 2nd QuarterDiane LeonesNessuna valutazione finora

- The CIA Tavistock Institute and The GlobalDocumento34 pagineThe CIA Tavistock Institute and The GlobalAnton Crellen100% (4)

- MRI BRAIN FINAL DR Shamol PDFDocumento306 pagineMRI BRAIN FINAL DR Shamol PDFDrSunil Kumar DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Bellak Tat Sheet2pdfDocumento17 pagineBellak Tat Sheet2pdfTalala Usman100% (3)

- Ebook Torrance (Dalam Stanberg) - 1-200 PDFDocumento200 pagineEbook Torrance (Dalam Stanberg) - 1-200 PDFNisrina NurfajriantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaishali Ancient City Archaeological SiteDocumento31 pagineVaishali Ancient City Archaeological SiteVipul RajputNessuna valutazione finora

- Sale DeedDocumento3 pagineSale DeedGaurav Babbar0% (1)

- Supplement BDocumento65 pagineSupplement BAdnan AsifNessuna valutazione finora

- English Proficiency Test (EPT) Reviewer With Answers - Part 1 - Online E LearnDocumento4 pagineEnglish Proficiency Test (EPT) Reviewer With Answers - Part 1 - Online E LearnMary Joy OlitoquitNessuna valutazione finora

- Demerger Impact on Shareholder WealthDocumento16 pagineDemerger Impact on Shareholder WealthDarshan ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- ID Kajian Hukum Perjanjian Perkawinan Di Kalangan Wni Islam Studi Di Kota Medan PDFDocumento17 pagineID Kajian Hukum Perjanjian Perkawinan Di Kalangan Wni Islam Studi Di Kota Medan PDFsabila azilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 22 NDocumento6 pagineLecture 22 Ncau toanNessuna valutazione finora

- COOKERY Grade 9 (Q1-W1)Documento2 pagineCOOKERY Grade 9 (Q1-W1)Xian James G. YapNessuna valutazione finora

- Casalla vs. PeopleDocumento2 pagineCasalla vs. PeopleJoan Eunise FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 Mesina v. PeopleDocumento7 pagine05 Mesina v. PeopleJason ToddNessuna valutazione finora

- Bobby Joe Public NoticeDocumento3 pagineBobby Joe Public NoticeUpscale International InvestmentsNessuna valutazione finora

- CS201 Midterm Solved MCQs With ReferenceDocumento4 pagineCS201 Midterm Solved MCQs With Referencegenome companyNessuna valutazione finora

- Pope Francis' Call to Protect Human Dignity and the EnvironmentDocumento5 paginePope Francis' Call to Protect Human Dignity and the EnvironmentJulie Ann BorneoNessuna valutazione finora

- (PC) Brian Barlow v. California Dept. of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 4Documento2 pagine(PC) Brian Barlow v. California Dept. of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora