Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Eugene Hill and The 5 MS: Executing The Due Diligence Plan: Lisa Cooke

Caricato da

Dan MelendezTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Eugene Hill and The 5 MS: Executing The Due Diligence Plan: Lisa Cooke

Caricato da

Dan MelendezCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms:

Executing the Due Diligence Plan

Lisa Cooke

Imagine receiving a thousand venture capital

(VC) proposals a yearall of them promising the

moonand having to discover the single shining

star. In any given year, we probably see

between ten to twenty plans a week. So thats a

thousand plans a year. We do serious work, read

the plan, and schedule a management meeting

on maybe fifty, says Eugene Hill. He is a

managing partner at SV Life Sciences in Boston,

whose team includes 31 professional portfolio

advisors1 managing 1.6 billion in capital.2

Hill compares the constant

onslaught of financing proposals

of recent years to trying to drink

from a fire hose. Since the early 1980s,

Hill has examined tens of thousands of

entrepreneurial proposals in the healthcare

venture capital world, but the number of

investments he has made from those mountains

of applications is in the low double-digits.

His due diligence process for investigating

these pitches may seem conservative to the

point of being merciless, but it also has made his

return on investment enviably consistent and

notably successful. There have been years when

Ive seen 1,500 business plans, issued a dozen

Theres

a huge no factor, for a whole

host of reasons, Hill says.

term sheets and invested in one deal.

Hill has been a speaker at a number of

Kauffman Fellows modules, and he spoke with

me several times over the summer.3 In this

article, I present what he shared about his 5

Ms of the due diligence process and the keys to

being one of the lucky few to get his funding goahead.

Origins of a Life Science Investor

It was pure serendipity that led Eugene Hill to

his profession as a healthcare venture capitalist.

Hired as an administrator for the Chief of Surgery

at Denver General Hospital in 1975 , Hill

discovered his passion for healthcare

methodologies and developing technologies. Im

not a trained scientist, says Hill. Healthcare

services are pure business execution. To pursue

his interest, he went to business school at night

to earn his MBA. (Figure 1 includes some offtopic points of interest.)

Much has changed since Hill, now 61, entered

healthcare venture capital. There were fewer

funds, says Hill, and the funds themselves were

much smaller. VCs were very engaged, active

investors, and there were few industry-specific

funds, says Hill, himself a life sciences investor.

Fund sizes today are larger and there is

increased specialization.

1 SV Life Sciences, SVLS Team,

http://www.svlsa.com/pages/team.php, para. 1.

2 SV Life Sciences, Welcome to SV Life Sciences,

http://www.svlsa.com/index.html, para. 2.

3 All Eugene Hill quotes are from my three telephone interviews in

July and August 2013, from our follow-up emails in September 2013,

or from Hills PowerPoint presentation on the 5 Ms.

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms

Last book read for pleasure: The Battle of

Bretton Woods, by Benn Steil

Last music downloaded: Mark Knopfler

Last concert attended: Bach Festival,

Carmel, CA

Where were you raised: Denver, Colorado

Family: Married, three children, two younger

sisters

Hobbies: Golf, tennis, skiing, collecting

antique oriental rugs

Last vacation destination: Aspen, Colorado

Professional philosophy: Do not go where

the path may lead, go instead where there is

no path, and leave a trail - Ralph Waldo

Emerson4

Personal quote: Invest in haste. You can

repent in your leisure.

Alternate career: None. Im a serial

healthcare services entrepreneur.

Figure 1. Off Topic with Eugene Hill. Image by

Kauffman Fellows Press.

The 5Ms: Separating Wheat from Chaff

Hills painstaking proposal-refinement process

delves deeper than the potential return on

investment, and is dependent upon whether the

opportunity is an initial investment, continuing

investment, or acquisition. The crux of his

the Five

Ms: Market, Management, Method,

Money, and Metrics.

philosophy involves what he calls

As to which M is the most important, Hill

admits there is a lot of debate in Silicon Valley

and among investors about whether management

or market is the chief ingredient in any venture.

I believe market characteristics are the primary

goal that you need to use as a screen. You can

have high-quality people and a really high-quality

strategy, but if the market characteristics dont

exhibit the right order of magnitude, or the right

order dynamic to permit the right amount of

profitability or monetization of the assets, its

4 This quote is widely attributed to Emerson (e.g., BrainyQuotes.com,

ThinkExist.com), but more reputable sites such as RWE.org and

EmersonCentral.com do not include it.

probably not going to make for a successful

venture return.

Hill has developed a

structured list of questions asked

of every entrepreneur who comes

through his door. The answers can

mean the difference between

Hills likely no and the all-toorare yes. Sometimes, even a correct

Over the years,

answer, when preceded with waffling or

uncertainty, is sufficient to crater the proposal.

Hills questions are the starting point in his

dissectionwhat he calls the Hierarchy of

Triageof a candidate for venture capital

injection.

M1: The Market

Hills examination of the market involves

quantifying the business case relative to a

number of factors. He investigates the market

size, growth rate, degree of competitive

penetration, concentration of participants,

pricing and profitability dynamics, and barriers

to entry.

Hill prefers to invest in disruptive tsunami

opportunities. Because todays markets are

winner take all, he says, with the top three

entrants having the dominant share in an

established market, a new entrant must be able

to dislodge the existing competition.

Technology Feasibility

As a specialist in life sciences investment, Hill

first looks into the technology behind the

company. The first question may seem almost

Can the company

actually make the item? In other

absurd in its simplicity:

words, Hill asks whether the company will use

off-the-shelf parts, or bleeding-edge technology

and the knowledge of a few intellectual heroes.

Even if the company can produce its intended

product or service, regulation can present

obstacles. Government interference can range

from mundane, bureaucratic blocking and

tackling, to halting the business altogether.

For example, a managed-care startup might

need an insurance license, which is a

straightforward mechanical exercise: applying

forthcoming, Kauffman Fellows Report volume 5

with state regulators and confirming that the

company has sufficient capital and experienced

personnel. Compare that path to a company

developing an Alzheimers medicationpotential

treatment for a disease that is largely still a

mystery to science, with physicians having only a

modest understanding of how the disease

progresses. Not only is it going to take years of

trials to know if the drug works, but those tests

are also going to be the basis for FDA approval.

The second companys path is both costly and

challenging.

Market Feasibility

The company also must prove it understands the

viability of entering the market. Its important

to get an idea around pricing and gross margin,

and how much R&D and marketing expense it will

take to get to the market, Hill says.

Part of Hills work at this stage is to

quantify how many customers

there arethe key distinction between the

addressable market and the accessible market.

The addressable market is how

many people could potentially

buy the product, as opposed to

the accessible market, which is

the number of people who

realistically will buy the product.

A new entrant into the mobile phone scene,

for example, has 200 million potential buyers in

the United States (addressable market).

However, the products accessible market

concerns how many people have already bought

phones and how often they replace thema

number that gets quickly reduced when factoring

brand loyalty and whatever penetration rates a

new entrant might have. Finally, while 200

million U.S. residents can buy a cell phone and

the average replacement cycle is three years, a

few vendors such as Apple, and Samsung control

a large percent of the market share and spend

hundreds of millions of dollars a year in

advertising each.

Unless a company has a product that is highly

differentiated, it is unlikely to achieve any kind

of market position. Even in a virgin market, a

company must be concerned about price,

performance, and features; but in this case, at

least, one can anticipate and manage adoption

rate.

Financial Risk

The concept of financial risk is associated with

the amount of money required to run the

enterprise. Usually, $10 million to $20 million is

a very important VC milestone, whether for FDA

approval and achieving a revenue rate, or for

opening a swath of stores that will sell a product

or service in volume. But what if it will take $300

million to reach this milestone? In that

circumstance, the only real exit for the VC is if

the company has a legitimate shot at an IPO or a

buyout. If the company is going to cost $2 billion,

then there are maybe a half-dozen firms in the

world that can finance that kind of reach.

As a result, it is imperative to set boundaries

on the amount and type of financing that can be

brought in over a given timeline. Raising $2

million can be done in 90 days; that is easier

than raising $20 million, which is exponentially

easier than $200 million.

Im asking myself whether this is going to happen

with debt or equity, whether the government will

assist or provide subsidies. You have to look at all

those things, and you have to look at what the

return on investment is.

Determining whether the product or service is

financeable on reasonable terms is vital.

It is not always wise to be first

to invest, especially with

companies that require huge upfront expenditures for

infrastructure. For instance, the first three

rounds of VC investors in FedEx lost moneyonly

investors in the fourth round came out ahead.

Something is always going to go wrong, Hill

says. You always provide a cushion, because

something will always cost more and take

longer.

Hill calls this oasis preparation. It may

result in the operation being slightly overfunded,

but thats a better scenario than the VC

equivalent of crossing the Sahara and running out

of food, water, and gasoline.

M2: The Management

Nearly as important as market opportunity is

determining whether the people in charge have

3

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms

the requisite experience and expertise to

execute.

Depending on the stage, circumstance, and the

size of the business, you require different skill sets

and different personal characteristics. Businesses

at different stages of development need different

things.

Management pedigree is key.

Missionary and Mercenary

For example, a startup needs an almost

missionary focus: a leader who gets up in the

morning with a visionary mindset and who sees

the big market opportunity and is not deterred

by noise or negativism. However, a missionary

cannot be driven solely by a psychic reward; a

mercenary attitude is also required. A missionary

executive will not necessarily succeed with a

business in its late stage of development, or in a

firm that is in need of a turnaround and facing

declining margins, mature products, or intense

competition.

In the course of his career, Hill has seen this

situation many times: People who are skilled at

running one stage of company development may

not be appropriate leaders in another stage.

The key, says Hill, is to find people whose

skill sets match the business opportunity, in

terms of content knowledge as well as the

experiential characteristics, and to anticipate

those transitions, Hill says.

CEOs get replaced approximately half the

time. To use a sports analogy, a startup usually

doesnt have a strong bench. They usually are

Replacing the CEO and

other top executives may seem

like a cruel blow to the team who

successfully chartered the

company to a critical

development point, but it is often

necessary for the company to

grow to maturation.

not deep.

These investments can take a long time. As you

transition a business from a startup to a growth

phase, you address the different challenges

businesses face. Its important to anticipate those

challenges and prepare everybody for those

transitions. Its rare that you see a CEO take a

business from startup all the way through

maturation.

Succession planning is obviously lower on the

priority list than getting the product to market,

ultimately, businesses that

succeed do so because of the

people involved.

but

We see a lot of businesses that meet market

characteristics that are attractive. Then you look

at the team, and your immediate conclusion is that

this is a team that isnt going to succeed. They

dont have the relevant experience, expertise, or

personality characteristics that enable them to

exploit the opportunity.

Fine-Toothed Comb

Hill always conducts background checks for

things like criminal activities or other icky

stuff; sometimes, however, the check turns out

to be unnecessary. Merely suggesting a

background check can open the confessional

floodgates. When we ask, Is there anything

else we need to know? the amount of stuff we

get is amazing, and horrifying, Hill says. The

most frequent falsification involves education

credentials. More seriously, in regulated

industries people have not disclosed past

criminal activities in their applications while

building the business, but in falsifying an

application to a regulator, that person has

already committed a crime.

Hill also has lawyers look over the paperwork

the company has amassed to date, looking for

fatal flaws. Many cash-poor startups have to

scrimp on legal advice, and things do not get

buttoned upthe IP may not be under control,

the companys books may not be audited, or

stock may have been sold and not accounted for

in ownership documents. Decimal points may be

misplaced in contracts; verbal agreements are

not notated.

Ive seen major gaps between what companies

thought their financials were and what we saw

when we came in with pros. None of this is a

problem until its a problem, [and] then its a huge

problem.

Face-to-Face Facts

Even management all-stars can have skeletons in

the closet. Hill likes to meet executives in both

forthcoming, Kauffman Fellows Report volume 5

business and social settings, to see how they

interact in unscripted situations. He often brings

his wife to a group dinner, because she finds out

things that he would never learn in a business

environment.

With companies that survive Hills rigorous

screening, he conducts a site visit to meet with

the management team and other principals, and

to check out the work environment. Hill always

takes a partner to avoid the inherent biases of

solo judgement.

At this stage of due diligence, credentials

mean less than the companys message and how

it is presented. For a tech company with a

scientist presenting the product or data who is a

neophyte to presentations, Hill cuts some slack.

If the sales and marketing guys stumble, thats a

red flag.

Glib, overconfident answers

also are a bad tactic for

management, especially when Hill

asks a hypothetical, speed of

light question that he knows is

baloney.

If they answer, Oh, yeah, then I know they are

bluffing. If they say, No, of course not, then I

know they are listening and have engaged their

brain before they engaged their mouth.

Hill also tries to gauge the pitch based on how

many previous VC presentations the company has

given. First-time efforts get some forgiveness,

but veterans need to nail it.

I want them to be efficient and preemptively

answer the majority of my questions. Im still

going to validate the answers they give me, but I

want them to at least put a stake in the ground.

And its absolutely okay for them to say, I dont

know the answer and Ill get back to you.

Once the pitch is complete, Hill takes a

thorough walk-around of the facility. He requests

that his tour be given by junior managers, not

executives, and during off hours if possible.

I

want to mingle with the worker

bees. I want a tour on the

graveyard shift, because theyre

always weird, and no one has told

them what they cant tell you, Hill

says. You learn a ton of stuff

when the executives arent

around.

This is his favorite part of the process,

because this sort of tour allows him to engage in

human capital valuation using the dissertation

theories of management guru Geoffrey Smart.5

Hill admits that initially he was a by-the-numbers

investor: I thought social science stuff was

malarkey. He is a convert because of Smarts

work.

Getting to know a companys culture speaks

volumes. A tech company does not have to have

a coat-and-tie dress code but it does need good

gear: A clean lab with high-quality, modern,

well-maintained equipment, even if the building

itself is old. If the office is a train wreck, with

bad discipline and garbage everywhere, how can

you trust their data when they cant even throw

their trash away? Hill says. Or it may go the

other way, with an early-stage startup choosing

palatial digs in the upscale part of town. Limited

resources should be spent on real technology,

not real estateits a matter of priorities.

M3: Method

If an entrepreneurial company can make it past

Hills first two rounds of questions, it is off to a

good start. However, the business methodology

can be a tricky path to navigate.

Drilling Down on the Value Proposition

Hill examines the companys value proposition.

In other words, what is the business model? Is it

a product, is it a service, or is it a mix of both?

Does the product save time, money, or both? Will

it succeed by increasing revenues or by slashing

costs? Will it beat competitors through higher

quality, by being quicker to market, or by being

a product revolution?

You need to know if its better-fastercheaper or a Brave New World6 equation.

5 See, e.g., Geoffrey H. Smart, The Art and Science of Human Capital

Valuation: Smart Assessment, Smarter Performance, Big Speak

Consulting white paper, 1998, http://www.bigspeak.com/consulting/

white-papers/Geoff-Smart_Horizontal-Human-Capita-Valuation.pdf;

Geoffrey H. Smart, Management Assessment Methods in Venture

Capital: Toward a Theory of Human Capital Valuation, dissertation,

Claremont Graduate University, 1998, http://www.ghsmart.com/

media/press/methods_in_venture_capital.pdf.

6 Hill uses this term frequently to refer to a certain type of

groundbreaking business entity. The phrase originates with the 1932

speculative fiction classic Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (New

York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006).

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms

Better-faster-cheaper is good.

You have a reference point that

you can verify because you know

a ton about the market. Brave

New World is tough because the

market doesnt exist yet, Hill says.

With Brave New World, even

with the best engineering teams,

companies often are at the limits

of material science. For example, as a

startup Intel had huge waste rates before they

figured out how to do integrated circuits

properly, Hill says. They had to invent clean

rooms and large-scale integration. It meant

building something for scale, and meeting

certain specifications; it also meant investing a

lot of money, well beyond the resources of most

venture capitalists.

Compare Intel with Cypress Semiconductor, a

company that came in later but was building

highly specialized chips sold mainly into the

defense sector. Cypress was able to carve out a

very nice niche building high-performance chips

that did not need to be produced in high

quantity, because they could sell them at a

premium for their superior performance. Their

plan did not require a Brave New World solution.

the problem with

better-faster-cheaper is a low

barrier to entry. If your firm was able to

Hill believes

find a price-slashing way to get ahead of the

competition, someone else can do it to you,

says Hill. Margin erosion ensues along with a race

to the bottom in a chase for customers and

investors, an unhealthy pursuit. Thats the

greater fool theory in action: unloading the

hot potato before everyone else realizes the idea

is a loser.

Special Sauce

All of these methodologies add up to a firm

identifying its special saucebe it a less

expensive way to address a problem, a better

distribution angle, a niche created through more

attractive product characteristics, or a patent

that will provide a high barrier to entry against

competitors. However, Hill finds that while many

believe in their value, few companies actually

have the secret sauce.

If somebody suggests that their economics are

fundamentally different from everybody elses,

then either they really have identified some

special sauceand that does happen, because

theyve cracked the codeor else theyre clueless.

the percentage of those with the

secret sauce is infinitesimally small.

Its a teeny minority.

And

Almost by definition of being a startup, there

are many places where things can go wrong. Hill

believes the most frequent problem is a lack of

focus, with companies trying to overreach and do

too many things.

In his book, Crossing the Chasm,7 Geoffrey

Moore talks about the difficulty of a company

progressing from the audience of early adopters

to the early majority consumers. It takes a very

different set of skills to cross that chasm and get

a product or service into the adoption cycle

where there is extremely high growth; it also

requires a lot of discipline to get there.

Many entrepreneurs get seduced by the idea that

there is a huge opportunity they can crack

overnight, and they lose focus and discipline. They

dilute their landing force across 98 beaches, rather

than putting all their weight behind establishing

one beachhead.

Hill cites VC veteran John Doerr, who says

companies frequently overestimate the

opportunity in the near term, and underestimate

the opportunity in the long term. Its more

important to establish a series of realistic

milestones in terms of time and resource,

providing a sufficient cushion, and achieving

them, says Hill. If you pick them correctly, you

can increase value along the way.

Personally, Hill says he is more

intrigued by the companies that

do not purport to have the special

sauce.

They may not have a patent-protected product;

they just have a great management team. It is

pure execution. Anybody else who can assemble

the right team could copy what some of these

7 Geoffrey A. Moore, Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling

Disruptive Products to Mainstream Customers, New York:

HarperCollins, 2002.

forthcoming, Kauffman Fellows Report volume 5

businesses do, but they will succeed simply

because they execute better.

M4: The Money

Next, Hill turns his attention to how the business

is going to operate on a daily basis. He looks

closely at the cash-flow statement, because it

tells him how the business is actually operating

even though most income statements are

completely illusory.

It boils down to a simple equation: How much

money is it going to take, and how long is it

going to take? Capital is more than cash,

obviously. An early question is whether the

entrepreneur anticipates using equity, debt

financing, government loans or grants, customer

down payments, or a combination of sources.

The last thing an entrepreneur wants to do is

dilute his share, so equity financing is often a

last resort.

Talking about money may be one of the most

time-consuming aspects of due diligence,

because this is why entrepreneurs are talking to

venture capital in the first place. The financiers

also want to make sure their money is spent

well, not wasted on lavish game rooms and

Christmas parties.

Hill makes a point of searching

for entrepreneurs who have lesscapital-intensive business plans.

Needing a lot of start-up capital is a red flag. He

asks, Is the money going to pay for people,

office space, or industrial equipment? What is

the best way to finance that?

In looking at employees, one factor is

whether there are only five people in the world

who can do a critical job, or fifty thousand who

can do it.

You would be surprised at how many businesses

financials just dont make any sense. Theyve

grossly underestimated the real amount of money

they are going to need to hire to get the best and

brightest, if thats what they need.

If the company is based in a remote location,

getting the best and brightest could be a

challenge; if the company is in San Francisco or

La Jolla, however, it had better be ready to open

its purse strings to attract and keep talent.

Then theres the almost-clichd, inflated

return on investment calculation by the

entrepreneureye candy for potential

investors, but often not grounded in reality. Hill

recalls meeting a group of eager Harvard

sophomores looking for funding whose healthcare

idea was intriguing, but unfocused. They were

trying to do five things, when any one of the five

would have been challenging enough by itself,

but they had all five mixed up together, Hill

says. Their equation detailed two years, $30

million in revenue, and $7 million in profit.

Ive been doing this for 35 years, and that would

have been unprecedented. Ive never seen it

happen. So they discredited themselves by putting

forth a proposition that on its surface was so

incredible no one would believe it. Thats an

example we see every day, where

something put forth is so impossibly

incredible, where if they are crazy

enough to think thats realistic, you

have to start asking whether every

other assumption is wrong.

Relating back to the Market equation, Hill

delves into what is causing the opportunity, and

what is driving it. Is it sustainable, an aberration,

or a time-limited condition?

Hill also warns against point valuation by

VC investors, who often use todays numbers to

gauge their expected return down the line.

Look at long-term trends, over five to seven

years. Markets are cyclical. There are times

when things are depressed, and times when they

Assuming your exit

valuation is based on todays

inflated market, you are going to

be in for a surprise, Hill says.

are inflated.

The answers to these questions inform the

VCs hoped-for return on investment over time.

From that point, Hill can project what he might

realistically try to extract from the venture,

should it be successful.

M5: The Metrics

The notion of metrics is to quantify as much of

the business opportunity as you can, Hill says. A

key question is how many potential customers

the company is chasing. If there are 10

customers, you can go visit them yourself; if

there are a million customers, youre not going

to see them personally.

7

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms

Next, Hill investigates the sales cycles. Who

are the customers and how do they buy these

things? Do they buy them at Wal-Mart, over the

Internet, or only on a request-for-proposal basis?

How many do they buy? Is it a $10, $100, or a $2

million product? Is the company selling at a price

dictated by the market, or can it set the price? Is

production scalable or sensitive to rapid volume

changes? The sales cycle dictates how much you

can afford to spend on promotion, which then

dictates your operating margin and things like

that, Hill says.

How a company forecasts its sales is a key

metric. Hill refers to the pipeline fallacy,

where a company might be overconfident in its

success rate in penetrating a market. Are its

forecasts based on actual customers, cash-inhand qualified prospects, prospects who have

been pitched but have not responded, or just

pie-in-the-sky suspects? Im trying to figure out

how credible all these numbers are, Hill says.

People

will use terminology like

pipeline, and you have to peel

the onion back to really see what

they are talking about."

Another stumbling block is if there is a solesource supplier somewhere in the mix. If there

is, now Im nervous. What happens if that

supplier goes out of business? What happens if

they raise the price? Im trying to see whether

the assumptions made are realistic, Hill says.

Knowing precisely where the product is in

development is a crucial element for a venture

investor. With a tech company, a product may be

in the alpha stage, just a big idea in someones

head and still in early development. It could be

in beta testing, where the product is functioning

and being debugged in a controlled environment.

Or, people may have actually paid for the

product and are giving feedback.

Then, of course, there is the product itself,

the numerous ways even a

savvy venture investor can slip

upHill calls it being deluded by

the demo. He admits to being blindsided

and

by nanocrystal developments at a leading

research university. This exciting medical

technology had been licensed, and a company

wanted to commercialize it for a specific

medical application. Hills group joined a few

others to fund it, but when the time came for

the actual technology transfer (moving outside

the university laboratory environment and into a

commercial environment), it took three times as

long and cost four times as much as anticipated.

The nanocrystals simply were not ready for prime

time.

Hill takes his share of the blame in this case,

speaking with a touch of chagrin.

We should have realized that these guys didnt

really have it fine tuned. A laboratory, in a supercontrolled environment, not even producing

consistently, cant produce at scale. There was a

huge amount of variability in quality control. There

were just a lot of things that hadnt been worked

out.

We didnt do enough work figuring out where

they were at, and the people that we charged with

doing the technology transfer didnt understand

how much work remained to be done. Because

they talked past each other, no one really nailed

exactly where things are were.

Hill sees this mistake happen all the time with

software company investors.

We will see a mockup. Somebody has developed a

series of screens, and the screens look pretty. You

can do some stuff with thembut theres nothing

behind them. The integration coding work is huge.

After seeing a lush, elegant

presentation, Hills first response

is, I want to see it in the field, not

where there is 24-7 support, but where I

can tell if its doing what its

supposed to do.

Hill is the first admit it: Even with all the

background checks, psychological profiling,

interviews, and market assessment, choosing the

right venture to back is still a judgment call.

A Prince among Frogs

What can an entrepreneur do to get to the head

of the line with Eugene Hill? Having an

established network of trusted connections

helps. Unsolicited proposals go the bottom of the

pile, if not the circular file.

We kiss a ton of frogs to find the prince, and there

may be more frogs than there used to be. In the

old world, pre-Web, pre-digital, where people had

forthcoming, Kauffman Fellows Report volume 5

to produce a hard-copy business plan and use the

U.S. mail, there was some sort of cost. Whereas

today, they go on the web, push a button, and

business plans fly through the ether.

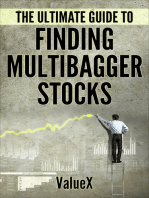

Figure 2 includes some of the

questions Hill has formulated

around the Five Ms; he uses the

answers to weed out the vast

majority of applicants. Both

entrepreneurs and VCs may find them useful.

Hill acknowledges that his methods are gained

from his own personal perspective, and modestly

refrains from categorizing it as some

comprehensive genius solution to due diligence.

Instead, he concludes, This is just a series of

lessons that Ive learned, sometimes with a lot of

blood, sweat, and tears. These are the

takeaways that Ive had over thirty years. This is

a journey, not a destination.

Lisa Cooke

A professional journalist and syndicated

columnist for the early part of her career, Lisa

has been a writer and content strategist for San

Francisco and Silicon Valley corporations and

startups for the last fifteen years. Her clients

have included Twitter, Adobe, Shutterfly,

Genentech, Zynga, Time Warner Cable, and the

Department of Defense.

Eugene Hill and the 5 Ms

The Market

The Money

What is the product and how many are

people going to buy?

How does the company plan to build and sell

the product?

Is the market large and growing fast?

Are the Intellectual Property barriers low?

What is their competitive advantage, and

how long will it take for them to achieve it?

Is the company in a declining market, with

intense competition, where a potential

turnaround situation exists because of

changed circumstances?

How much money is it going to take to get to

market, and where are the funds coming

from?

Does the company need to spend extra to

lure the best and brightest minds to create

the product, or can it make do with a

cheaper rank-and-file?

Is it a visionary startup, in its growth phase,

or approaching the buyout phase?

Is it a product or service business?

How does distribution happen?

What are the pricing dynamics?

Can a fast follower easily come in and erode

margins?

The Management

The Metrics

Is the company selling to thousands of

customers or to a limited audience?

How will the customers actually buy the

product?

Do the team leaders have sufficient

experience and talent to make the venture

succeed?

How much will the product cost, and what is

the operating margin?

How much will the company spend on

promotion?

Can they handle the transition period from

startup to successful operation?

Is the company a price setter or price taker?

Do any of the top executives have skeletons

in their closet?

Is their model consistent with other

competitors?

Does the management presentation ring

true, or are they glib and full of bluster?

Is there is single-source component supplier

that could raise the price or simply

disappear?

Did lawyers ensure their documents line up,

or are filings filled with potentially costly

errors and omissions?

The Method

Will the companys value proposition succeed

through increased revenue, or cost savings,

or by working better-faster-cheaper?

Is it a Brave New World proposition?

Is the company B2B or B2C?

What is the companys special sauce?

Is the business planning to grow organically

or through acquisition?

Figure 2. Due diligence questions from Eugene Hills Five Ms. Image by Kauffman Fellows Press.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- BCG - Corporate Venture Capital (Oct - 2012)Documento21 pagineBCG - Corporate Venture Capital (Oct - 2012)ddubyaNessuna valutazione finora

- William J O'Neil1 LindaDocumento22 pagineWilliam J O'Neil1 LindaLinda Salim100% (1)

- Li-Lu - A Value InvestorDocumento316 pagineLi-Lu - A Value Investoraakash87100% (1)

- The Dividend Imperative: How Dividends Can Narrow the Gap between Main Street and Wall StreetDa EverandThe Dividend Imperative: How Dividends Can Narrow the Gap between Main Street and Wall StreetNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Freedom Blueprint: 7 Steps to Accelerate Your Path to ProsperityDa EverandFinancial Freedom Blueprint: 7 Steps to Accelerate Your Path to ProsperityNessuna valutazione finora

- Teco VFD Operating ManualDocumento69 pagineTeco VFD Operating ManualStronghold Armory100% (1)

- Design and Estimation of Dry DockDocumento78 pagineDesign and Estimation of Dry DockPrem Kumar100% (4)

- LRS Trading StrategyDocumento24 pagineLRS Trading Strategybharatbaba363Nessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Good Profit: by Charles G. Koch | Includes AnalysisDa EverandSummary of Good Profit: by Charles G. Koch | Includes AnalysisNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.1 OUM Cloud Approach Presentation-ManagerDocumento24 pagine4.1 OUM Cloud Approach Presentation-ManagerFeras AlswairkyNessuna valutazione finora

- CE ThesisDocumento210 pagineCE ThesisKristin ArgosinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Life-Saving Rules: Tool Box Talk SeriesDocumento86 pagineLife-Saving Rules: Tool Box Talk SeriesSalahBouzianeNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 08 - Entrepreneurial Strategy and Competitive DynamicsDocumento56 pagineChapter 08 - Entrepreneurial Strategy and Competitive DynamicsJasmin NgNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4: Contemporary Models of Development and UnderdevelopmentDocumento40 pagineChapter 4: Contemporary Models of Development and UnderdevelopmentJaycel Yam-Yam Verances100% (1)

- The Peter Lynch Approach PDFDocumento6 pagineThe Peter Lynch Approach PDFSamder Singh KhangarotNessuna valutazione finora

- High Tech Start Up, Revised And Updated: The Complete Handbook For Creating Successful New High Tech CompaniesDa EverandHigh Tech Start Up, Revised And Updated: The Complete Handbook For Creating Successful New High Tech CompaniesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (31)

- Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development PDFDocumento7 pagineEntrepreneurship and Small Business Development PDFSenelwa Anaya80% (10)

- Zook On The CoreDocumento9 pagineZook On The CoreThu NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3: New Venture Planning: Startup Long-Term GrowthDocumento14 pagineUnit 3: New Venture Planning: Startup Long-Term GrowthSam SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramy Ahmed - Reasons For Business DiscontinuationDocumento10 pagineRamy Ahmed - Reasons For Business Discontinuationرامي أبو الفتوحNessuna valutazione finora

- #Executive SummariesDocumento5 pagine#Executive SummariesNgô TuấnNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing MyopiaDocumento3 pagineMarketing MyopiaHosahalli Narayana Murthy PrasannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Serious Money Straight TalkDocumento142 pagineSerious Money Straight TalkoptimusnowNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 NVCDocumento27 pagine1 NVCAnida AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary, Analysis and Review of George Akerlof's and et al Phishing for PhoolsDa EverandSummary, Analysis and Review of George Akerlof's and et al Phishing for PhoolsNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Download Entrepreneurial Finance 5th Edition Leach Test BankDocumento35 pagineFull Download Entrepreneurial Finance 5th Edition Leach Test Bankcoctilesoldnyg2rr100% (21)

- Value: InvestorDocumento4 pagineValue: InvestorAlex WongNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Start A Hedge Fund and Why You Probably ShouldntDocumento20 pagineHow To Start A Hedge Fund and Why You Probably ShouldntJohn ReedNessuna valutazione finora

- OceanofPDF - Com How To Be A Billionaire - Martin S FridsonDocumento11 pagineOceanofPDF - Com How To Be A Billionaire - Martin S FridsonBasheer AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Internship 20117Documento44 pagineInternship 20117Tangirala AshwiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Conscious CapitalismDocumento12 pagineConscious Capitalismchmbhvps78Nessuna valutazione finora

- ENTPDocumento50 pagineENTPbikashhhNessuna valutazione finora

- SW3 TechnoDocumento2 pagineSW3 TechnoRYNANDREW BASIANONessuna valutazione finora

- Serious Money Straight TalkDocumento142 pagineSerious Money Straight TalkAscaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Entrepreneurial FinanceDocumento25 pagineIntroduction To Entrepreneurial FinancechanNessuna valutazione finora

- Thinking To Create New Opportunities: Nicholas Hall Conference: NewDocumento4 pagineThinking To Create New Opportunities: Nicholas Hall Conference: Newapi-86536392Nessuna valutazione finora

- Finance 1 NotesDocumento4 pagineFinance 1 NotesnathanaelzeidanNessuna valutazione finora

- Raphael Luis D. Icban MGT110/AY02Documento7 pagineRaphael Luis D. Icban MGT110/AY02Jordan AlcanseNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship Is The Practice of Starting New Organizations or RevitalizingDocumento6 pagineEntrepreneurship Is The Practice of Starting New Organizations or RevitalizingASIF RAFIQUE BHATTINessuna valutazione finora

- FIN561 Week 1 HomeworkDocumento2 pagineFIN561 Week 1 HomeworknguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Innovation (Review and Analysis of Carlson and Wilmot's Book)Da EverandInnovation (Review and Analysis of Carlson and Wilmot's Book)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mergers Acquisitions The Role of HRMDocumento24 pagineMergers Acquisitions The Role of HRMRavindra MistryNessuna valutazione finora

- LulDocumento4 pagineLulRoy GamerzzNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship and Innovation The Keys To Global Economic RecoveryDocumento24 pagineEntrepreneurship and Innovation The Keys To Global Economic RecoveryglamisNessuna valutazione finora

- "Current Scenario of Venture Capital": Contemporary Issue On Seminar A Study OnDocumento38 pagine"Current Scenario of Venture Capital": Contemporary Issue On Seminar A Study OnneetuNessuna valutazione finora

- Sharmaine Joy A. Rodrigueza Bsba 4-ADocumento35 pagineSharmaine Joy A. Rodrigueza Bsba 4-ACristine Balangitan MasangcayNessuna valutazione finora

- Tomorrow's Dells - 5 StocksDocumento8 pagineTomorrow's Dells - 5 Stockspatra77Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is An Entrepreneur?: Key TakeawaysDocumento7 pagineWhat Is An Entrepreneur?: Key TakeawaysYram GambzNessuna valutazione finora

- The 18 Immutable Laws of Corporate ReputationDocumento3 pagineThe 18 Immutable Laws of Corporate ReputationAnna CarolineNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay Draft 1 - Group DDocumento6 pagineEssay Draft 1 - Group DNguyen HoangNessuna valutazione finora

- Wilson, Karen PaperDocumento35 pagineWilson, Karen PaperamaliadcpNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Practice: Viewpoint: The Invisible Advantage by Jonathan Low and Pam Cohen KalafutDocumento5 pagineBest Practice: Viewpoint: The Invisible Advantage by Jonathan Low and Pam Cohen KalafuthdfcblgoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Direct Public Offerings (Review and Analysis of Field's Book)Da EverandDirect Public Offerings (Review and Analysis of Field's Book)Nessuna valutazione finora

- GMO - Profits For The LongRun - Affirming The Case For QualityDocumento7 pagineGMO - Profits For The LongRun - Affirming The Case For QualityHelio KwonNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrep 2Documento4 pagineEntrep 2brytzprintsNessuna valutazione finora

- Value Investor Insight 12 13 Michael Porter InterviewDocumento6 pagineValue Investor Insight 12 13 Michael Porter InterviewharishbihaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: Samuel Dave D. Heroy Course & Year: BSIT - IV Id Number: 17-0111-720Documento4 pagineName: Samuel Dave D. Heroy Course & Year: BSIT - IV Id Number: 17-0111-720Andrjstne SalesNessuna valutazione finora

- ENTREPRENEURSHIP ch1Documento8 pagineENTREPRENEURSHIP ch1bikalpadevkota30Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1.) What Are The Factors Considered by Investors Regarding Their Decision To Invest in Stocks?Documento6 pagine1.) What Are The Factors Considered by Investors Regarding Their Decision To Invest in Stocks?Hailley DensonNessuna valutazione finora

- EntrepreneurshipDocumento27 pagineEntrepreneurshipPutriAuliaRamadhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Ravshan Suyunov Final EnterpreneurshipDocumento5 pagineRavshan Suyunov Final EnterpreneurshipzazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Angel Investment in The China Market.Documento17 pagineBusiness Angel Investment in The China Market.grandiosetreasu18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Startup Long-Term Growth Venture CapitalDocumento7 pagineStartup Long-Term Growth Venture CapitalNiño Rey LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Theoriesofentrepreneurship 160902051135 PDFDocumento20 pagineTheoriesofentrepreneurship 160902051135 PDFthakurneNessuna valutazione finora

- Swot Analysis of PTCLDocumento5 pagineSwot Analysis of PTCLM Aqeel Akhtar JajjaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study of Improving Productivity in Warehouse WorkDocumento5 pagineCase Study of Improving Productivity in Warehouse WorkRohan SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- TSPrintDocumento9 pagineTSPrintapi-3734769Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sangfor NGAF Introduction 8.0.5 FinalDocumento24 pagineSangfor NGAF Introduction 8.0.5 FinalAlbarn Paul AlicanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Fee ChallanDocumento1 paginaFee ChallanMuhammad UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Swifty Loudspeaker KitDocumento5 pagineSwifty Loudspeaker KitTNNessuna valutazione finora

- Masonry - Block Joint Mortar 15bDocumento1 paginaMasonry - Block Joint Mortar 15bmanish260320Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unreal Tournament CheatDocumento3 pagineUnreal Tournament CheatDante SpardaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab 1: Basic Cisco Device Configuration: Topology DiagramDocumento17 pagineLab 1: Basic Cisco Device Configuration: Topology DiagramnhiNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF CatalogEngDocumento24 paginePDF CatalogEngReal Gee MNessuna valutazione finora

- User Manual For Online Super Market WebsiteDocumento3 pagineUser Manual For Online Super Market WebsiteTharunNessuna valutazione finora

- HIV Sero-Status and Risk Factors of Sero-Positivity of HIV Exposed Children Below Two Years of Age at Mityana General Hospital in Mityana District, UgandaDocumento14 pagineHIV Sero-Status and Risk Factors of Sero-Positivity of HIV Exposed Children Below Two Years of Age at Mityana General Hospital in Mityana District, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNessuna valutazione finora

- Solved MAT 2012 Paper With Solutions PDFDocumento81 pagineSolved MAT 2012 Paper With Solutions PDFAnshuman NarangNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages of Group Decision MakingDocumento1 paginaAdvantages of Group Decision MakingYasmeen ShamsiNessuna valutazione finora

- CEN ISO TR 17844 (2004) (E) CodifiedDocumento7 pagineCEN ISO TR 17844 (2004) (E) CodifiedOerroc Oohay0% (1)

- 6seater Workstation B2BDocumento1 pagina6seater Workstation B2BDid ProjectsNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Getting StartedDocumento44 pagine01 Getting StartedAsbokid SeniorNessuna valutazione finora

- Zypper Cheat Sheet 2Documento1 paginaZypper Cheat Sheet 2norbulinuksNessuna valutazione finora

- TUPT AdmissionDegreeLadderizedDocumento1 paginaTUPT AdmissionDegreeLadderizedromerqazwsxNessuna valutazione finora

- BeartopusDocumento6 pagineBeartopusDarkon47Nessuna valutazione finora

- Iphone App DevelopmentDocumento18 pagineIphone App DevelopmentVinay BharadwajNessuna valutazione finora

- ASME VIII Unfired Vessel Relief ValvesDocumento53 pagineASME VIII Unfired Vessel Relief Valvessaid530Nessuna valutazione finora

- BS en 00480-6-2005 PDFDocumento8 pagineBS en 00480-6-2005 PDFShan Sandaruwan AbeywardeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 23 Electromagnetic Waves: SolutionsDocumento16 pagine23 Electromagnetic Waves: SolutionsAnil AggaarwalNessuna valutazione finora