Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Continuing Relevance of Strategy

Caricato da

mwananzambi1850Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Continuing Relevance of Strategy

Caricato da

mwananzambi1850Copyright:

Formati disponibili

15huff (ds)

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 123

Human Relations

[0018-7267(200101)54:1]

Volume 54(1): 123130: 015583

Copyright 2001

The Tavistock Institute

SAGE Publications

London, Thousand Oaks CA,

New Delhi

The continuing relevance of strategy

Anne Sigismund Huff

My father-in-law understood what accounting was, or at least he was satisfied with his definition. He was much less sure about strategy, and I was

not much help. It has never been easy for me to explain my field to others,

although an example will sometimes suffice. Strategic decisions have longterm impact, I said to my father-in-law a number of years ago. Your decision

not to open a branch store in Aspen was strategic.

This kind of definition can lead to further conversation, or stop it. I

didnt realize it was so important at the time, he might have said, giving me

an entre to Mintzbergs (1978) arguments about realized strategy. Instead

he dismissed my example by contending, I couldnt give it much thought,

because I didnt have anyone who could handle it. Unfortunately, I had not

read Edith Penrose (1959) at the time.

I recently have had an increasing number of such unsatisfying conversations. Though I have much better stories to tell, I still worry that collectively we are falling short. Strategy is too often dismissed in this globalizing

world of shifting alliances and instantaneous electronic connections as timeconsuming and irrelevant. I think one problem is definitional.

In the last several decades, organization behavior, organization theory,

human relations and other areas of management inquiry have grown and

developed, yet they do not seem to have had the difficulties defining their

subject that we have had. The conversations we start, among ourselves and

with others, are rarely brought to conclusion; they tend to falter in the face

of new enthusiasms. The millennium is a good point to examine some of these

starting points, and contemplate how we might further a fascinating, but

elusive, area of inquiry.

123

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

15huff (ds)

124

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 124

Human Relations 54(1)

What do strategists do?

Strategy is about action. Verbs are therefore appropriate vehicles for summarizing our various foci of attention. Four in particular describe the post-World

War II period in which business policy metamorphosed into strategy. They are

interesting as contradictory yet complementary definitions of the field.

Fight

Historians almost always point to our legacy from military strategy. From

this point of view, the strategist identifies and analyzes the enemy, develops

an overall campaign, hopefully chooses the battlefield, and orchestrates a

sequence of encounters intended to achieve victory. Sun Tzus insights from

the sixth century BC continue to be relevant:

Warfare is the art (tao) of deceit. Therefore, when able, seem to be

unable; when ready, seem unready; when nearby, seem far away, and

when far away, seem near. . . . Attack where [the enemy] is not prepared; go by way of places where it would never occur to him that you

would go.

(Sun Tzu, 1993, 1045)

Porter (1980, 1990) used surprisingly similar ideas to help strategists think

about their position with respect to suppliers and buyers, as well as competitors. Game theory now works to formalize such insights. The job is to

vanquish or at least dominate an opponent. Relative profit is typically the

measure of success. This perspective is relevant even to strategists in public

and not-for-profit organizations, who must identify a purpose and way of

operating that backers will find more deserving than other alternatives. These

strategists find it easy to speak of the battle against cancer, or the arts need

to capture a larger share of recreational expenditures.

I think a military perspective has such widespread and enduring appeal

because it makes valid statements about human nature. We like to win. The

successful military strategist is cunning, but also taps the energies unleashed

by threat and conflict. Adrenalin is a powerful, and addictive, force.

Garden

The definition of successful strategy that I learned first, however, was less

combative. Pioneering work in business policy by Andrews (1971) and others

emphasized that successful strategists must find a fit between the organization

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

15huff (ds)

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 125

Huff

The continuing relevance of strategy

and its environment. As the strategy field gained momentum in the late

1970s, companies were investing large sums in environmental scanning and

planning, academics were conducting large-scale studies of diversification

and other strategic alternatives that provided empirical evidence for viable

choices. The orientation was more developmental than combative.

Formal planning now has declined in appeal, and time horizons have

shortened, yet Hamel and Prahalad (1994) are avoiding hand-to-hand

combat when they urge companies to seek unexplored white spaces. Option

theorists similarly are in a gardening mode when they suggest small investments to keep multiple options alive under conditions of uncertainty. The

overall idea, articulated by the resource-based view of the firm, is that success

depends on skills and capabilities within the organization. Competitive

advantage is still the aim, but learning and knowledge management (rather

than gamesmanship) are the methodologies to follow.

This perspective on strategy also conforms to human nature. In our

private as well as public lives, we seek patterns in order to make sense of our

situation, and use them to actively position ourselves for desired results.

Sustain

It is easy to observe, however, that promising initiatives falter and that strategy implementation is much more difficult than strategy formulation. The

forces of inertia are internal and external. Orchestrating activities in different parts of the organization and its larger environment takes time and leads

to obligations that are not easily abandoned. New hires may be less committed to old initiatives and often bring new enthusiasms. Across the organization, varied and often conflicting agendas tend to blur initial strategic

coherence. Quinns (1978) work described why strategy is therefore logically

incremental as it responds to different opportunities. Processual studies, such

as those led by Pettigrew (e.g. 1991), provided additional insight into how

organizational realities temper grand strategic ideas.

One sensible response, especially given the scale and scope of modern

organizations, is to institutionalize success when it is achieved. Nelson and

Winters (1982) work provides the rationale for routines that encapsulate the

expertise of individuals and groups, and transcend their tenure. Prescriptions

from the resource-based theory of the firm are compatible. The organizational resources required for sustained advantage are not only valuable, rare

and inimitable, but also embedded in organizational processes (Barney,

1991).

Once again, these approaches to strategy are in accord with human

nature. We base many actions on simplified conclusions from our own

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

125

15huff (ds)

126

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 126

Human Relations 54(1)

experience and the observation of others. If not, we would each be immobilized by choices faced before leaving for work. Woody Allen is said to

have observed that 80 percent of success is just showing up. The sustained

strategy that is homeostatically renewed over time follows the same logic.

Invent

On the other hand, previous experience is often inadequate. The opposite of

routinization is invention. Insight has always been part of the strategy conversation, but it has recently become more salient. Jobs and economic growth

are more attributable to small start-up companies than we realized. Entrepreneurship courses are flourishing. A significant number of students now

start or join e-commerce firms without even completing their degrees. These

firms offer products, services and methods of delivery that are being identified for the first time. Quinn et al. (1997), and other notable observers, have

turned their attention to the need for innovation.

Interestingly, a key heroic moment, discovering strategy itself, typically

takes place off stage. Winning strategic ideas are magic. We dont really know

how they happen. At best we can talk about facilitating factors (money, time,

training, infrastructure, etc.). But this definition also seems right. As a race,

we have a history of extraordinary accomplishments achieved by people who

somehow imagine what had been unimaginable.

Do we need new ideas to strategize in a new economy?

Obviously, a more detailed discussion could be advanced and other areas of

attention specified, but these four verbs indicate some important things about

the field of business policy and strategy over the last 50 years or so. We have

followed rather conflicting paths. In fact, we have participated in and fed the

faddish search for direction that leads companies to adopt and then drop

expensive enthusiasms. Re-engineering comes to mind; e-commerce is the

currently consuming subject.

Pendulum swings, in academic as well as corporate concerns, do draw

attention to the limits of past frameworks. Thus, the bounce is often corrective. E-commerce is not just about new technology, it also addresses consumer desires for comparison, autonomy, and more immediate gratification

that were neglected by previous strategies.

New developments in academic theorizing have similarly redressed

the limitations of past definitions. Despite the compelling nature of new

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

15huff (ds)

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 127

Huff

The continuing relevance of strategy

arguments, however, I believe old accounts continue to be relevant, and

easily justified by individual and organizational behavior. Intrinsically,

strategy is not linear, and is likely to be even more complex under economic conditions that emphasize speed and facilitate change. We cannot

expect to find one, simple focus of attention.

On the contrary, our efforts to date can be criticized for being too narrowly focused, even though we have offered needed diversity. Two limitations

in particular need further attention. We have overly emphasized the rational,

and under-emphasized the moral. The following verbs suggest ways of thinking about these neglected aspects of strategy. They point to a single cluster

of concerns that are again contradictory, yet complementary.

Husband

It should not have been surprising that my father-in-law knew more about

strategy and its long-term impacts than I realized. For example, while we

were still in graduate school, he suggested that my husband and I buy a

mountain cabin. It seemed expensive and somewhat peripheral to our lives,

but we bought it and were glad to have vacations ready-made. I did not

immediately appreciate, however, that J.O. was giving us more than financial and lifestyle advice. It was only after he died that I recognized he must

have meant the cabin to be an anchor that would keep drawing us back to

family. I am sure he had the idea our siblings and children would be more

likely to return to Colorado with our cabin as an attractive magnet.

This kind of husbanding is difficult to achieve in a global, hurry-up

world, with widely accepted success formulas and pressures for immediate

results. Responsibility for long-term consequences has not been emphasized

in US-dominated strategies, though European and Asian publics and strategists tend to be more attentive. As large companies eclipse more nation states,

and both large and small companies find it easier to reinvent and relocate, I

believe we should define strategy in ways that not only attend to longer-term

implications of current strategy but also consider second-order effects. Faith

in market mechanisms, in particular, must be re-examined in a world of

imperfect markets. We should, I believe, become more responsible.

One point for departure in thinking about appropriate strategy can

be found in Etzionis (1996) work on community, another in Mansbridges

(1990) edited book Beyond self-interest. Closer to home, Selznicks (1957)

classic Leadership in administration argues for the importance of values and

character. More recent work on sustainable strategies is relevant, as is Peter

Schwartzs (1991) book, The art of the long view.

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

127

15huff (ds)

128

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 128

Human Relations 54(1)

Enact

Most of these works still fall within the rationalist mind-set that has dominated the strategy field. I believe it also is time to emphasize different epistemologies. Karl Weick (1979, 1995), who does not to my knowledge consider

himself a strategy theorist, has done a good job of articulating the idea that

the sense people make of their situations tends to enact the conditions they

assume. Again, relevant issues are more widely discussed outside of the

United States than within it (e.g. von Krogh & Roos, 1996). Again, a globalizing environment requires much more attention to enactment precisely

because organizations are becoming so dominant.

Strategists have always changed the world in ways they could not fully

anticipate. Surely, some leaders of the East India Companies considered the

dramatic impact of their activities on the conditions of trade in the 1660s,

though they could not comprehend all the conditions they were instrumental

in enacting. Similar thoughts about consequences occupy contemporary theorists and strategists, yet in the end we tend to ignore the recursive aspects

of strategy. We create campaigns to develop new markets, for example, but

shy away from accepting responsibility for creating a world in the marketing campaigns image.

In my opinion, this is an urgent agenda for the immediate future, and

one that requires reconsidering past definitions of strategy. Deceit is deeply

ingrained in the military strategists activities, for example; enactment suggests

that it creates a world in which duplicity dominates trustworthy behavior.

Every strategic perspective is similarly suspect. Inventors argue that any

product they do not invent will be invented by others, to their profit and our

loss. Thus, we are developing and beginning to market biological products

with dramatic benefits but unknowable side-effects. Public debates on such

difficult issues are increasing, but they are inconclusive. It is too easy for strategists, and strategy theorists, to consign such concerns to their private, rather

than professional lives and confront the ironies implicit in their actions.

Conclusion

A few years ago it was asserted that the study of strategy could not progress

unless we showed more discipline and decided on a limited number of key

variables to focus our attention (Montgomery et al., 1989). The argument

makes some sense within a specific line of inquiry, over relatively limited

periods of time. It is based, however, on a positivist view of scientific inquiry

that is losing ground in other academic conversations, and is of limited

relevance in the new economy we should now be trying to understand.

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

15huff (ds)

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 129

Huff

The continuing relevance of strategy

The strategy field can be praised for exploring some inherent tensions

of purposeful action. We have considered conflict, but also cooperation and

fit. We take invention as our domain, but also acknowledge the importance

of routinization. The field thus establishes some compelling and interesting

parameters for purposeful action.

Nonetheless, we still have work to do. Organizations create the conditions within which we all must live. Too many of us have resolutely looked

away from the longer-term, social consequences of organizational activities.

We have not acknowledged that strategy itself is implicated in the very conditions it tries to change. I hope that we confront these issues more directly

in the years ahead. If we do so, we make an important bid for remaining

relevant.

References

Andrews, K.R. The concept of corporate strategy. Homewood, IL: Dow-Jones Irwin, 1971.

Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management,

1991, 7, 99120.

Etzioni, A. The new golden rule: Community and morality in a democratic society. New

York: Basic Books, 1996.

Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C.K. Competing for the future. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press, 1994.

Mansbridge, J.J. Beyond self-interest. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Mintzberg, H. Patterns of strategy formation. Management Science, 1978, 24, 93448.

Montgomery, C.A., Wernerfelt, B. & Balakrishnan, S. Strategy content and the research

process: A critique and commentary. Strategic Management Journal, 1989, 10, 18997.

Nelson, R.R. & Winter, S.G. An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Penrose, E.T. The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley, 1959.

Pettigrew, A.M. Managing change for competitive success. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1991.

Porter, M.E. Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press, 1980.

Porter, M.E. The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press, 1990.

Quinn, J.B. Strategic change: Logical incrementalism. Sloan Management Review, 1978,

Fall, 721.

Quinn, J.B., Baruch, J.J. & Zien, K.A. Innovation explosion: Using intellect and software

to revolutionize growth strategies. New York: Free Press, 1997.

Schwartz, P. The art of the long view. New York: Doubleday, 1991.

Selznick, P. Leadership in administration. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, 1957.

Sun Tzu. The art of war. (Translated, with an introduction and commentary, by Roger T.

Ames.) New York: Ballantine, 1993.

Von Krogh, G. & Roos, J. Managing knowledge. London: Sage, 1996.

Weick, K.E. The social psychologizing of organizing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979.

Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995.

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

129

15huff (ds)

130

20/11/00 3:15 pm

Page 130

Human Relations 54(1)

Anne Sigismund Huff is Professor of Strategic Management at the University of Colorado, Boulder, USA, with a joint appointment at Cranfield

School of Management in the UK. She received her PhD from Northwestern University and has been on the faculty at UCLA and the University of Illinois. Her research interests focus on strategic change, both

as a dynamic process of interaction among firms and as a cognitive

process affected by the interaction of individuals over time. In addition to

articles on various topics related to strategic change, her publications

include Mapping strategic change (Wiley, 1990), which discusses alternatives for visualizing strategic reasoning. Professor Huffs professional

activities include serving on the editorial board of the Strategic Management Journal, The Journal of Management Studies and The British Journal of

Management, and acting as the strategy editor for the book series Foundations in organization science (Sage Publications). In 19989, she was

President of the Academy of Management.

[E-mail: Anne.Huff@Colorado.edu]

Downloaded from hum.sagepub.com at University of Leicester Library on July 25, 2016

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Intellectual Capital and The Capital Market - A Review and SynthesisDocumento34 pagineIntellectual Capital and The Capital Market - A Review and Synthesismwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Personality Tests in Accounting ResearchDocumento32 paginePersonality Tests in Accounting Researchmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Family and Religion in Luba LifeDocumento13 pagineFamily and Religion in Luba Lifemwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- How It Worked - The Story of Clarence SnyderDocumento331 pagineHow It Worked - The Story of Clarence Snydermwananzambi1850100% (1)

- Ethical Dimensions of The Rana Plaza Scandal - Business EthicsDocumento4 pagineEthical Dimensions of The Rana Plaza Scandal - Business Ethicsmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theory of Organizational Culture and EffectivenessDocumento21 pagineTheory of Organizational Culture and Effectivenessmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kant Vs Mill DeontologyDocumento4 pagineKant Vs Mill Deontologymwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Recovery Programme For Depression Booklet PDFDocumento68 pagineRecovery Programme For Depression Booklet PDFmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Insignificance and InferiorityDocumento6 pagineInsignificance and Inferioritymwananzambi1850100% (1)

- Grant Robert M-Foundations of Strategy-Extract From Chapter 1 - Closing Case The King Of-Pp40-44Documento4 pagineGrant Robert M-Foundations of Strategy-Extract From Chapter 1 - Closing Case The King Of-Pp40-44mwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Deedpol Form UKDocumento10 pagineDeedpol Form UKmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pro Tools Reference GuideDocumento1.284 paginePro Tools Reference GuideChunka OmarNessuna valutazione finora

- Possible Interview Questions For Christian JobsDocumento2 paginePossible Interview Questions For Christian Jobsmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Porter's Competitive Advantage, RevisitedDocumento4 paginePorter's Competitive Advantage, Revisitedmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Making Swot Analysis WorkDocumento5 pagineMaking Swot Analysis Workmwananzambi1850100% (1)

- Marketing in Non-Profit OrganizationsDocumento32 pagineMarketing in Non-Profit Organizationsmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- ZARA Final ReportDocumento30 pagineZARA Final ReportFlorinRobertStanescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Iowa State University: Department of Economics Working Papers SeriesDocumento32 pagineIowa State University: Department of Economics Working Papers Seriesmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Critical ReaderDocumento2 pagineCritical Readermwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vygotsky's Learning TheoryDocumento2 pagineVygotsky's Learning Theorymwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Writing EssaysDocumento8 pagineWriting Essaysmwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Organising Your TimeDocumento5 pagineOrganising Your Timemwananzambi1850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Critical Writing v1 0Documento4 pagineCritical Writing v1 0Sarah WalkerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- PDF of Tally ShortcutsDocumento6 paginePDF of Tally ShortcutsSuraj Mehta100% (2)

- Department of Education: Income Generating ProjectDocumento5 pagineDepartment of Education: Income Generating ProjectMary Ann CorpuzNessuna valutazione finora

- Revit 2023 Architecture FudamentalDocumento52 pagineRevit 2023 Architecture FudamentalTrung Kiên TrầnNessuna valutazione finora

- Hindi ShivpuranDocumento40 pagineHindi ShivpuranAbrar MojeebNessuna valutazione finora

- Biblical Foundations For Baptist Churches A Contemporary Ecclesiology by John S. Hammett PDFDocumento400 pagineBiblical Foundations For Baptist Churches A Contemporary Ecclesiology by John S. Hammett PDFSourav SircarNessuna valutazione finora

- Better Photography - April 2018 PDFDocumento100 pagineBetter Photography - April 2018 PDFPeter100% (1)

- Minuets of The Second SCTVE MeetingDocumento11 pagineMinuets of The Second SCTVE MeetingLokuliyanaNNessuna valutazione finora

- CoSiO2 For Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis Comparison...Documento5 pagineCoSiO2 For Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis Comparison...Genesis CalderónNessuna valutazione finora

- CEN and CENELEC Position Paper On The Proposal For CPR RevisionDocumento15 pagineCEN and CENELEC Position Paper On The Proposal For CPR Revisionhalexing5957Nessuna valutazione finora

- ArcGIS Shapefile Files Types & ExtensionsDocumento4 pagineArcGIS Shapefile Files Types & ExtensionsdanangNessuna valutazione finora

- Linear Dynamic Analysis of Free-Piston Stirling Engines OnDocumento21 pagineLinear Dynamic Analysis of Free-Piston Stirling Engines OnCh Sameer AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 AcknowledgementDocumento8 pagine2 AcknowledgementPadil KonamiNessuna valutazione finora

- CSEC SocStud CoverSheetForESBA Fillable Dec2019Documento1 paginaCSEC SocStud CoverSheetForESBA Fillable Dec2019chrissaineNessuna valutazione finora

- Countable 3Documento2 pagineCountable 3Pio Sulca Tapahuasco100% (1)

- Answer Key To World English 3 Workbook Reading and Crossword Puzzle ExercisesDocumento3 pagineAnswer Key To World English 3 Workbook Reading and Crossword Puzzle Exercisesjuanma2014375% (12)

- Acampamento 2010Documento47 pagineAcampamento 2010Salete MendezNessuna valutazione finora

- Monitor Stryker 26 PLGDocumento28 pagineMonitor Stryker 26 PLGBrandon MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- SEC CS Spice Money LTDDocumento2 pagineSEC CS Spice Money LTDJulian SofiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Docsity Detailed Lesson Plan 5Documento4 pagineDocsity Detailed Lesson Plan 5Sydie MoredoNessuna valutazione finora

- Paramount Healthcare Management Private Limited: First Reminder Letter Without PrejudiceDocumento1 paginaParamount Healthcare Management Private Limited: First Reminder Letter Without PrejudiceSwapnil TiwariNessuna valutazione finora

- 21st CENTURY TECHNOLOGIES - PROMISES AND PERILS OF A DYNAMIC FUTUREDocumento170 pagine21st CENTURY TECHNOLOGIES - PROMISES AND PERILS OF A DYNAMIC FUTUREpragya89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Five Kingdom ClassificationDocumento6 pagineFive Kingdom ClassificationRonnith NandyNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Travelling Waves Principle in Protection Systems and Related AutomationsDocumento52 pagineUse of Travelling Waves Principle in Protection Systems and Related AutomationsUtopia BogdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 9 WorkbookDocumento44 pagineGrade 9 WorkbookMaria Russeneth Joy NaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Meriam Mfc4150 ManDocumento40 pagineMeriam Mfc4150 Manwajahatrafiq6607Nessuna valutazione finora

- DIFFERENTIATING PERFORMANCE TASK FOR DIVERSE LEARNERS (Script)Documento2 pagineDIFFERENTIATING PERFORMANCE TASK FOR DIVERSE LEARNERS (Script)Laurice Carmel AgsoyNessuna valutazione finora

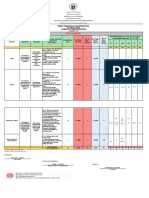

- Revised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10Documento6 pagineRevised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10May Ann GuintoNessuna valutazione finora

- 3M 309 MSDSDocumento6 pagine3M 309 MSDSLe Tan HoaNessuna valutazione finora

- WinCC Control CenterDocumento300 pagineWinCC Control Centerwww.otomasyonegitimi.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Centrifuge ThickeningDocumento8 pagineCentrifuge ThickeningenviroashNessuna valutazione finora