Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The End of The Anglo-American Order

Caricato da

Hoang DucTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The End of The Anglo-American Order

Caricato da

Hoang DucCopyright:

Formati disponibili

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

http://nyti.ms/2gDAv47

The End of the Anglo-American Order

For decades, the United States and Britains vision of democracy and

freedom defined the postwar world. What will happen in an age of

Donald Trump and Nigel Farage?

By IAN BURUMA NOV. 29, 2016

One of the strangest episodes in Donald Trumps very weird campaign was the

appearance of an Englishman looking rather pleased with himself at a rally on

Aug. 24 in Jackson, Miss. The Englishman was Nigel Farage, introduced by

Trump as the Man Behind Brexit. Most people in the crowd probably didnt

have a clue who Farage the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party

actually was. Yet there he stood, grinning and hollering about our

independence day and the real people, the decent people, the ordinary

people who took on the banks, the liberal media and the political establishment.

Trump pulled his face into a crocodile smile, clapped his hands and promised,

Brexit plus plus plus!

Brexit itself the decision to withdraw Britain from the European Union,

notwithstanding the almost universal opposition from British banking, business,

political and intellectual elites was not the main point here. In his rasping

delivery, Trump roared about Farages great victory, despite horrible namecalling, despite all obstacles. Quite what name-calling he had in mind was fuzzy,

but the message was clear. His own victory would be like that of the Brexiteers,

only more so. He even called himself Mr. Brexit.

Many friends and experts I spoke to in Britain resisted the comparison

between Trumpism and Brexit. In London, the distinguished conservative

historian Noel Malcolm told me that his heart sank when I compared the two.

Brexit, he said, was all about sovereignty. British democracy, in his view, would

be undermined if the British had to abide by laws passed by foreigners they didnt

vote for. (He was referring to the European Union.) The Brexit vote, he

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

1/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

maintained, had little to do with globalization or immigration or working-class

people feeling left behind by the elites. It was primarily a matter of democratic

principle.

Malcolm seemed to think that Brexit voters, including former industrial

workers in Britains rust-belt cities, were moved by the same high-minded

principles that had made him a convinced Brexiteer. I had my doubts.

Resentment about Polish, Romanian and other European Union citizens coming

to Britain to work harder for less money played an important part. As did the

desire to poke the eye of an unpopular elite, held responsible for the economic

stagnation in busted industrial cities. And the simple dislike of foreigners in

Britain should never be underestimated.

In the United States, too, I found resistance to the idea that Brexit was a

harbinger of a Trump victory. I was assured over and over by liberal friends that

Trump would never be president. American voters were too sensible to fall for his

hateful demagogy. Trump, I was told, was a product of peculiarly American

strains of populism that flare up periodically, like the anti-immigrant nativism in

the 1920s or Huey P. Long in 1930s Louisiana, but would never reach as far as the

White House. Traditional American populism of this kind, directed at the rich,

bankers, immigrants or big business, could, in any case, not be usefully compared

with English hostility to the European Union, because there was no supranational

political union the United States belonged to.

And yet Trump and Farage quickly recognized what they shared. In Scotland,

where Trump happened to be reopening a golf resort the day after the Brexit vote,

he pointed out the parallels. Brexit, Trump said to the Scots who voted

overwhelmingly against it, was a great thing: The British had taken back their

country. Phrases like sovereignty, control and greatness fired up the

crowds in both Trumps and Farages campaigns. You might think they meant

something different by those words. Farage and his allies, many of them English

nationalists, wanted to wrest national sovereignty from the European Union. But

from whom or what does Trump want to take his country back? Trump has

gestured at the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization

as noxious elements run by international elites to the detriment of the American

working man. But I cant imagine that these institutions fill most of his followers

with rage.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

2/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

In fact, most international institutions, including the I.M.F. and NATO, were

set up under American auspices, to promote the interests of the United States and

its allies. European unification, and the resulting European Union, too, have not

only been approved of but also vociferously encouraged by American presidents

before Trump. But his America First sentiments for that is what they are at this

point, more than a policy are hostile to these organizations. And so, by and

large, are the likes of Nigel Farage.

So Farage and Trump were speaking about the same thing. But they have

more in common than distaste for international or supranational institutions.

When Farage, in his speech in Jackson, fulminated against the banks, the liberal

media and the political establishment, he was not talking about foreign bodies

but about the aliens in our midst, as it were, our own elites who are, by

implication, not real, ordinary or decent. And not only Farage. The British

prime minister, Theresa May, not a Brexiteer before the referendum, called

members of international-minded elites citizens of nowhere. When three High

Court judges in Britain ruled that Parliament, and not just the prime ministers

cabinet, should decide when to trigger the legal mechanism for Brexit, they were

denounced in a major British tabloid newspaper as enemies of the people.

Trump deliberately tapped into the same animus against citizens who are not

real people. He made offensive remarks about Muslims, immigrants, refugees

and Mexicans. But the deepest hostility was directed against those elitist traitors

within America who supposedly coddle minorities and despise the real people.

The last ad of the Trump campaign attacked what Joseph Stalin used to call

rootless cosmopolitans in a particularly insidious manner. Incendiary

references to a global power structure that was robbing honest working people

of their wealth were illustrated by pictures of George Soros, Janet Yellen and

Lloyd Blankfein. Perhaps not every Trump supporter realized that all three are

Jewish. But those who did cannot have missed the implications.

When Trump and Farage stood on that stage together in Mississippi, they

spoke as though they were patriots reclaiming their great countries from foreign

interests. No doubt they regard Britain and the United States as exceptional

nations. But their success is dismaying precisely because it goes against a

particular idea of Anglo-American exceptionalism. Not the traditional self-image

of certain American and British jingoists who like to think of the United States as

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

3/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

the City on the Hill or Britain as the sceptered isle splendidly aloof from the

wicked Continent, but another kind of Anglo-American exception: the one shaped

by World War II. The defeat of Germany and Japan resulted in a grand alliance,

led by the United States, in the West and Asia. Pax Americana, along with a

unified Europe, would keep the democratic world safe. If Trump and Farage get

their way, much of that dream will be in tatters.

Intheyears when most of Europe was overrun by the Nazis or fascist

dictatorships, the Anglo-American allies were the last hope of freedom,

democracy and internationalism. I grew up in the world they shaped. My native

country, the Netherlands, was freed in 1945, six years before I was born, by

British and North American troops (with the help of some very brave Poles).

Those of us with no direct memories of this had still seen movies like The

Longest Day, about the Normandy landings. John Wayne, Robert Mitchum and

Kenneth More and his bulldog were our liberating heroes.

This was, of course, a childish conceit. For one thing, it left out the Soviet

Red Army, which liberated my father, who was forced to work in a factory in

Berlin along with other young men who, under German occupation, refused to

sign a loyalty oath to the Nazis. But the victorious Anglo-Saxon nations, especially

the United States, largely shaped the postwar Western world we lived in. The

words of the Atlantic Charter, drawn up by Churchill and Roosevelt in 1941,

resonated deeply throughout a war-torn Europe: Trade barriers would be

lowered, peoples would be free, social welfare would advance and global

cooperation would ensue. Churchill called the charter not a law, but a star.

Pax Americana, in which Britain played the role of special junior partner,

whose specialness was perhaps more keenly felt in London than in Washington,

was based on a liberal consensus. Not only NATO, set up to protect Western

democracies, chiefly against the Soviet threat, but also the ideal of European

unification were born from the ashes of 1945. Many Europeans, liberals as well as

conservatives, believed that only a united Europe would stop them from tearing

their continent apart again. Even Winston Churchill, whose heart was more

invested in Commonwealth and Empire, was in favor of it.

The Cold War made the exceptional role of the victorious allies even more

vital. The West, its freedoms protected by the United States, needed a plausible

counternarrative to Soviet ideology. This included a promise of greater social and

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

4/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

economic equality. Of course, neither the United States, with its long history of

racial prejudice and occasional fits of political hysteria, like McCarthyism, nor

Britain, with its tenacious class system, ever quite lived up to the shining ideals

they presented to the postwar world. Nonetheless, the image of exceptional

Anglo-American liberty held up, not only in countries that had been occupied

during the war but in the defeated nations, Germany (at least in the western half)

and Japan, as well.

Americas prestige was greatly bolstered not just by the soldiers who helped

liberate Europe but also by the men and women back home who fought to make

their society more equal and their democracy more inclusive. By struggling

against the injustices in their own country, figures like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther

King Jr. or the Freedom Riders or indeed President Obama kept the hope of

American exceptionalism alive. As did the youth culture of the 1960s. When

Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident playwright and later president, hailed Frank

Zappa, Lou Reed and the Rolling Stones as his political heroes, he was not being

frivolous. Under communist oppression, the pop music of America and Britain

represented freedom. Europeans born not long after World War II often

professed to hate the United States, or at least its politics and wars, but the

expressions of their hostility were almost entirely borrowed from America itself.

Bob Dylan received this years Nobel Prize for literature, not least because the

Swedish jury of baby boomers grew up with his words of protest.

The ideal of exceptional Anglo-Saxon liberties obviously goes back much

further than the aftermath of Hitlers defeat, let alone Bob Dylan and the Stones.

Alexis de Tocquevilles admiring account of American democracy in the 1830s is

well known. Much less famous are his writings on Britain in the same period.

Born soon after the French Revolution, Tocqueville was haunted by the question

of why Britain, with its mighty aristocracy, was spared such an upheaval. Why did

the British people not rebel? His answer was that the social system in Britain was

just open enough to allow a person to hope that with hard work, ingenuity and

luck, he could rise in society. The British version of the American dream: The

Great Gatsby may be the great American novel, but Gatsby could have existed in

Britain too.

In practice, there were probably not all that many rags-to-riches stories in

19th-century Britain. But the fact that Benjamin Disraeli, the son of Sephardic

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

5/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

Jews, could become prime minister, and an earl, no less, provided the basis for

many generations in Europe to believe in Britain as an exceptional country. Jews

from Russia or Lithuania, or from Germany, like my own great-grandparents,

flocked to Britain as immigrants in the hope that they, too, could become English

gentlemen.

Anglophilia, like the American dream, may have been based on myths, but

myths can be potent and long-lasting. The notion that sufficient effort and talent

can beat the odds has been especially important in Britain and the United States.

Anglo-American capitalism can be harsh in many ways, but because free markets

are receptive to new talent and cheap labor, they have spawned the kind of

societies, pragmatic and relatively open, where immigrants can thrive, the very

kind that rulers of more closed, communitarian, autocratic societies tend to

despise.

Wilhelm II, kaiser of Germany until 1918, when his country was defeated in

the First World War, which he had done his best to unleash, was such a figure.

Half English himself, he called England a nation of shopkeepers and described it

as Juda-England, a country corrupted by sinister alien elites, where money

counted more than the virtues of blood and soil. In later decades, this kind of

anti-Semitic rhetoric was more often aimed at the United States. The Nazis were

convinced that Jewish capitalists ruled America, not just in Hollywood but in

Washington and, naturally, New York. This notion is still commonly held, though

less in Europe than in the Middle East and some parts of Asia. But talk about

citizens of nowhere, sinister cosmopolitan elites and conspiratorial bankers fits

precisely in the same tradition. A terrifying irony of contemporary AngloAmerican populism is the common use of phrases that were traditionally used by

enemies of the English-speaking countries.

Yet even those who dont go along with the kaisers loathsome words

recognize that liberal economics, as practiced since the middle of the 19th century

in Britain and the United States, has a darker side. It does not allow for much

redistribution of wealth or protection of the most vulnerable citizens. There have

been exceptions: Roosevelts New Deal, for instance, or Britains postwar Labor

government under Clement Attlee, which created free national health care, built

better public housing, improved education and guaranteed other blessings of the

welfare state. British working-class men who risked their lives for their country

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

6/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

during the war expected no less. On the whole, however, Britain and the United

States have, compared with many Western countries, generally set greater store

on individual economic freedom than on the ideal of egalitarianism. And nothing

creates such swift and radical social change as unfettered free enterprise.

The Reagan-Thatcher revolution in the 1980s deregulating financial

services, closing down coal mines and manufacturing plants and hacking away at

the benefits of the New Deal and the British welfare state was regarded by

many conservatives, on both sides of the Atlantic, as a triumph for AngloAmerican exceptionalism, a great coup for freedom. Europeans outside Britain

were more skeptical. They tended to see Thatcherism and Reaganomics as

ruthless forms of economic liberalism, making some people vastly richer but

leaving many more out in the cold. Nonetheless, in order to compete, many

governments began to emulate the same economic system.

That this happened at the end of the Cold War was no coincidence. The

collapse of Soviet communism was celebrated, rightly, as the final liberation of

Europe. Countries, left behind on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain after World

War II, were free at last. The first President Bush spoke about the new world

order, led by the only superpower left standing. The Reagan-Thatcher revolution

appeared to have triumphed.

But the end of communism in the West also had other, less desirable

consequences. The horrors of the Soviet empire tainted other forms of leftism,

including social democratic ideals, which in fact had been anti-communist. Even

as the end of history was declared and the Anglo-American liberal democratic

model was expected to be unrivaled forever, many began to believe that all forms

of collectivist idealism led straight to the gulag. Thatcher once declared that there

was no such thing as society, just individuals and families. People had to be

forced to take care of themselves.

Radical economic liberalism did more to destroy traditional communities

than any social-democratic governments ever did. Thatchers most implacable

enemies were the miners and industrial workers. The neoliberal rhetoric was all

about prosperity trickling down from above. But it never quite worked out that

way. Those workers and their children, now languishing in impoverished rustbelt cities, received another blow in the banking crisis of 2008. Major postwar

institutions, like the I.M.F., which the United States set up in 1945 to secure a

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

7/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

more stable world, no longer functioned properly. The I.M.F. did not even see the

crisis coming. Large numbers of people, who never recovered from the crash,

decided to rebel and voted for Brexit and for Trump.

NeitherBrexitnor Trump are likely to bring great benefits to these voters.

But at least for a while, they can dream of taking their countries back to an

imaginary, purer, more wholesome past. This reaction is not only sweeping across

the United States and Britain. The same thing is happening in other countries,

including some with long liberal democratic traditions, like the Netherlands.

Twenty years ago, Amsterdam was seen as the capital of everything wild and

progressive, the kind of place were cops openly smoke pot (another myth, but a

telling one). The Dutch thought of themselves as the world champions of racial

and religious tolerance. Of all European countries, the Netherlands was the most

firmly embedded in the Anglosphere. Now the most popular political party,

according to the latest polls, is led practically as a one-man operation by Geert

Wilders, an anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant, anti-European Union firebrand who

hailed Trumps victory as the coming of a patriotic spring.

In France, Marine Le Pen, who shares Wilderss enthusiasm for Trump,

might be the next president. Poland and Hungary are already ruled by populist

autocrats who reject the kind of liberalism that Eastern European dissidents once

struggled so hard to achieve. Norbert Hofer, a man of the far right, could become

the next president of Austria.

Does this mean that Britain and the United States are no longer exceptional?

Perhaps. But I think it is also true to say that the very idea of Anglo-American

exceptionalism has made populism in those countries more potent. The selfflattering notion that the Western victors in World War II are special, braver and

freer than any other people, that the United States is the greatest nation in the

history of man, that Great Britain the country that stood alone against Hitler

is superior to any European let alone non-European country has not only led to

some ill-conceived wars but also helped to paper over the inequalities built into

Anglo-American capitalism. The notion of natural superiority, of the sheer luck of

being born an American or a Briton, gave a sense of entitlement to people who, in

terms of education or prosperity, were stuck in the lower ranks of society.

This worked quite well until the last decades of the last century. Not only

were the fortunes of working- or lower-middle-class people in Britain beginning

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

8/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

to dwindle compared with those of the rich, who were steadily getting richer, but

it gradually became clear even to the most insular Britons that they were doing

much worse than the Germans, the Scandinavians and the Dutch, worse even

than the French, Britains oldest rivals. One way of venting their rage was to fight

in soccer stadiums, taunting German fans by mimicking British bombers and

bellowing slogans about winning the war.

The so-called football hooligans remained an embarrassing minority, but

there were other ways to express the same feelings. The European Union, for

which most British people had never felt a great love, actually made many parts of

Britain more prosperous. The blight of the old industrial cities and mining towns

was not a result of European Union policies. But it was easy for Euro-skeptics to

deflect popular attention from domestic problems by blaming foreigners who

were supposedly running the show in Brussels. Europhobes liked to claim that

this was not why we fought the war. The specter of not just Hitler but also

Napoleon was sometimes evoked. Spitfires and talk of Britains finest hour made

a rhetorical comeback in the UKIP campaign to leave Europe. Some pro-Brexit

politicians even praised the greatness of the British Empire. Taking back

control by leaving the European Union is not going to make most people in

Britain more prosperous. The contrary is more likely to be true. But it takes the

sting out of relative failure. It feeds the desire to feel exceptional, entitled, in

short, to be great again.

Something similar has happened in the United States. Not only were even the

least privileged Americans told that they lived in Gods own country, but white

Americans, however impoverished and undereducated, had the comforting sense

that there was always a group beneath them, who did not share their entitlement,

or claim to greatness, a class of people with a darker skin. With a Harvardeducated black president, this fiction became increasingly difficult to sustain.

Trump and the leaders of Brexit had a fine instinct for these popular feelings.

In a way, Trump is a Gatsby gone sour. He played on the wounded pride of large

communities and inflamed the passions of people who fear the changes that make

them feel abandoned. In the United States, this brought out old strains of

nativism. In Britain, English nationalism is the main force behind Brexit. But in

both cases, taking back our country means a retreat from the world that the

Anglo-Americans envisaged after 1945. English nationalists have opted for a

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

9/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

modern version of Splendid Isolation (paradoxically, a term coined to describe

British foreign policy under Benjamin Disraeli). Trump wants to put America

First.

BrexitBritainand Trumps America are linked in their desire to pull down

the pillars of Pax Americana and European unification. In a perverse way, this

may herald a revival of a special relationship between Britain and the United

States, a case of history repeating itself not exactly as farce but as tragi-farce.

Trump told Theresa May that he would like to have the same relationship with

her that Ronald Reagan had with Margaret Thatcher. But the first British

politician to arrive at Trump Tower to congratulate the president-elect was not

the prime minister or even the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, but Nigel Farage.

Trump and Farage, beaming like schoolboys in front of Trumps gilded

elevator, gloated over their victories by repeating the same word that once made

their respective countries exceptional: freedom. In the privacy of Trumps

home, Farage suggested that the new president should move Winston Churchills

bust back into the Oval Office. Trump thought this a splendid idea.

A month before Trumps election and three months after the Brexit vote, I

visited the great military historian Sir Michael Howard at his home in rural

England. As a young man, Howard fought the Germans as an officer in the British

Army. He landed in Italy in 1943 and took part in the decisive battle of Salerno,

for which he was awarded the Military Cross. John Wayne and Kenneth More

were a fantasy. Sir Michael was the real thing. He is 95 years old.

After lunch at a local pub, just a few miles from where my grandparents used

to live, we talked about Brexit, the war, American politics, Europe and our

families. The setting could not have been more English, with the pale autumn sun

setting over the rolling hills of Berkshire. Like my great-grandparents, Sir

Michaels maternal grandparents were German Jews who moved to England,

where they did very well. Like mine, his family of immigrants became utterly

British. In addition to being Regius professor of history at Oxford University,

Howard taught at Yale. He knows America well and has no illusions about the

special relationship, which he believes was invented by Churchill and was

always much overblown.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

10/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

Sitting in his drawing room, with books piled up around us, many of them

about World War II, I wanted to hear his thoughts on Brexit. He replied in a tone

of resigned melancholy more than outrage. Brexit, he said, is accelerating the

disintegration of the Western world. Contemplating that world, so carefully

constructed after the war he fought in, he said: Perhaps it was just a bubble in an

ocean. I asked him about the special Anglo-American relationship. Ah, the

special relationship, he said. It was a necessary myth, a bit like Christianity.

But now where do we go?

Where indeed? The last hope of the West might be Germany, the country

that Michael Howard fought against and that I hated as a child. Angela Merkels

message to Trump on the day after his victory was a perfect expression of

Western values that are still worth defending. She would welcome a close

cooperation with the United States, she said, but only on the basis of democracy,

freedom and respect for the law and the dignity of man, independent of origin,

skin color, religion, gender, sexual orientation or political views. Merkel spoke as

the true heiress of the Atlantic Charter.

Germany, too, once thought it was the exceptional nation. This ended in a

worldwide catastrophe. The Germans learned their lesson. They no longer wanted

to be exceptional in any way, which is why they were so keen to be embedded in a

unified Europe. The last thing Germans wanted was to lead other countries,

especially in any military sense. This is the way Germanys neighbors wished it as

well. Pax Americana seemed vastly preferable to a revival of German

exceptionalism. I still think so. But looking once more at that photograph of the

Donald and Farage, baring their teeth in glee, thumbs held high, with the gold

from the elevator door glinting in their hair, I wonder whether Germany might

not be compelled to question a lesson it learned a little too well.

Ian Buruma is a professor at Bard College. His most recent book, Their Promised

Land, will come out in paperback in January.

SignupforournewslettertogetthebestofTheNewYorkTimesMagazine

deliveredtoyourinboxeveryweek.

AversionofthisarticleappearsinprintonDecember4,2016,onpageMM39oftheSunday

Magazinewiththeheadline:ExitWounds.

2016TheNewYorkTimesCompany

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

11/12

11/30/2016

The End of the Anglo-American Order - The New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/magazine/the-end-of-the-anglo-american-order.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

12/12

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Astrology Print OutDocumento22 pagineAstrology Print OutNaresh BhairavNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- AddictionDocumento110 pagineAddictionpranaji67% (3)

- Mozart SongsDocumento6 pagineMozart Songscostin_soare_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Atmakaraka in Arudha LagnaDocumento2 pagineAtmakaraka in Arudha Lagnaa1n2u3s4h5a60% (1)

- Holmes, M. (2006) - Polycarp of Smyrna, Letter To The Philippians. The Expository Times, 118 (2), 53-63Documento11 pagineHolmes, M. (2006) - Polycarp of Smyrna, Letter To The Philippians. The Expository Times, 118 (2), 53-63Zdravko Jovanovic100% (1)

- Check ListDocumento46 pagineCheck ListTamer KhalifaNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Diligence ChecklistDocumento6 pagineDue Diligence ChecklistNimmala GaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Diligence ChecklistDocumento6 pagineDue Diligence ChecklistNimmala GaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Diligence ChecklistDocumento6 pagineDue Diligence ChecklistNimmala GaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Diligence ChecklistDocumento6 pagineDue Diligence ChecklistNimmala GaneshNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemingway's Themes of Love and War in A Farewell to ArmsDocumento6 pagineHemingway's Themes of Love and War in A Farewell to ArmsNoor Ul AinNessuna valutazione finora

- Extrasensory Perception in Naqshbandi SufismDocumento7 pagineExtrasensory Perception in Naqshbandi SufismZach David100% (1)

- Is Arabic The Language of Adam or of Paradise. Author - Ibn Hazm Al-AndalusiDocumento4 pagineIs Arabic The Language of Adam or of Paradise. Author - Ibn Hazm Al-AndalusiFaizal Rakhangi100% (1)

- Spain Government Warnings On Covid 19 PandemicDocumento4 pagineSpain Government Warnings On Covid 19 PandemicHoang DucNessuna valutazione finora

- The Long-Term Legacy of The Khmer Rouge Period in Cambodia: Damien de WalqueDocumento45 pagineThe Long-Term Legacy of The Khmer Rouge Period in Cambodia: Damien de WalqueHoang DucNessuna valutazione finora

- Fidic ShannonDocumento28 pagineFidic ShannonHoang DucNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation of Law Firm On FIDICDocumento24 paginePresentation of Law Firm On FIDICHoang DucNessuna valutazione finora

- Funding Valuation Worksheet 3Documento3 pagineFunding Valuation Worksheet 3Hoang DucNessuna valutazione finora

- Employment Application Form: Transpennine ExpressDocumento12 pagineEmployment Application Form: Transpennine ExpressChristopher Brian StarkNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Subramanian Swamy Vs State of Tamil Nadu & Ors On 6 December, 2014Documento20 pagineDr. Subramanian Swamy Vs State of Tamil Nadu & Ors On 6 December, 2014sreevarshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ackerman, 2009. The Essential Elements of Dabrowski's Theory of Positive Disentegrationa and How They Are ConnectedDocumento16 pagineAckerman, 2009. The Essential Elements of Dabrowski's Theory of Positive Disentegrationa and How They Are ConnectedJuliana OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Faisalabad Ramadan Calendar 2024 UrdupointDocumento2 pagineFaisalabad Ramadan Calendar 2024 Urdupointchalishahidiqbal380Nessuna valutazione finora

- SK Kantan Permai student listsDocumento25 pagineSK Kantan Permai student listsJes02Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mahabharata Series on Morality, Ethics & ConductDocumento49 pagineMahabharata Series on Morality, Ethics & ConductGerman BurgosNessuna valutazione finora

- 241 472 1 SMDocumento7 pagine241 472 1 SMKomang Anggi WulandariNessuna valutazione finora

- Hazrat Molana احمد Lahoree باتیں کرامات واقعاتDocumento24 pagineHazrat Molana احمد Lahoree باتیں کرامات واقعاتMERITEHREER786100% (2)

- Normal 60518af729171Documento2 pagineNormal 60518af729171Laxmi PrasannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Greek and Roman MythologyDocumento7 pagineGreek and Roman Mythologypaleoman8Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gidan Dan HausaDocumento9 pagineGidan Dan Hausadanmalan224Nessuna valutazione finora

- Choosing Values That Will Give You The Future You WantDocumento47 pagineChoosing Values That Will Give You The Future You WantOmar OlivaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Day of JudgementDocumento3 pagineDay of Judgementrumaisa awaisNessuna valutazione finora

- Featured Articles Weekly ColumnsDocumento40 pagineFeatured Articles Weekly ColumnsB. MerkurNessuna valutazione finora

- Spiritual Well-Being and Resiliency of The Vocationist Seminarians in The PhilippinesDocumento23 pagineSpiritual Well-Being and Resiliency of The Vocationist Seminarians in The PhilippinesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sikh Rehats: Rihxi Rhy Soei Isk Myrw) Euh Twkuru My Aus KW Cyrw)Documento6 pagineSikh Rehats: Rihxi Rhy Soei Isk Myrw) Euh Twkuru My Aus KW Cyrw)Bhai Kanhaiya Charitable TrustNessuna valutazione finora

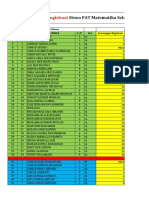

- Data Siswa PAT Matematika Selasa, 12 Mei 2020: RegistrasiDocumento14 pagineData Siswa PAT Matematika Selasa, 12 Mei 2020: RegistrasiNakaila SadilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dastangoi and The Tales That BindDocumento2 pagineDastangoi and The Tales That BindRupa AbdiNessuna valutazione finora

- Imam ShafiDocumento6 pagineImam Shafim.salman732Nessuna valutazione finora

- NASES ProgramDocumento4 pagineNASES ProgramMarco CavallaroNessuna valutazione finora

- AnnesleyJames Fictions of Globalization2006Documento209 pagineAnnesleyJames Fictions of Globalization2006Przemysław CzaplińskiNessuna valutazione finora

- From The Director's Desk: ActivitiesDocumento4 pagineFrom The Director's Desk: ActivitiesVivekananda KendraNessuna valutazione finora