Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Parallel Images: The Real, The Ghost and The Cinema - International Journal of The Image, 2013 - Anat Zanger

Caricato da

Anat ZangerTitolo originale

Copyright

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Parallel Images: The Real, The Ghost and The Cinema - International Journal of The Image, 2013 - Anat Zanger

Caricato da

Anat ZangerCopyright:

VOLUME 3 ISSUE 1

The International Journal of the

Image

__________________________________________________________________________

Parallel Images

The Real, the Ghost and the Cinema

ZANGER ANAT YONAT

ontheimage.com

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

http://ontheimage.com/

First published in 2013 in Champaign, Illinois, USA

by Common Ground Publishing

University of Illinois Research Park

2001 South First St, Suite 202

Champaign, IL 61820 USA

www.CommonGroundPublishing.com

ISSN: 2154-8560

2013 (individual papers), the author(s)

2013 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground

All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under

the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written

permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact

<cg-support@commongroundpublishing.com>.

The International Journal of the Image is a peer-reviewed scholarly journal.

Parallel Images: The Real, the Ghost and the

Cinema

Zanger Anat Yonat, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Abstract: A film asks its viewers to believe that the filmic world, a world of light and shadow,

is real. As Christian Metz observed in 1979, one of the main paradoxes in cinema is that

between absence and presence. This is perhaps the reason why contemporary cinema has to be

very careful about the way in which it employs possible worlds in order to build and rebuild

its imagined world. This paper explores the ways in which images are engaged in constructing

and deconstructing cinematic worlds. First, I will discuss a few types of labyrinths and rhizomes

in Eschers graphic works. Then, I will introduce two films and their various modes of engaging

ghost pictures: Michelangelo Antonionis Blow-Up (1966) and Cronenbergs Videodrome

(1982). Through these films, I will tackle the issue of parallel cinematic worlds. Could it be

that cinema-including postmodernist cinema-has not yet renounced its symbiosis with the

real?

Keywords: Moving Images, Labyrinth, Rhizome and Parallel Worlds, The Real in Cinema,

Postmodernism, Escher

For postmodernist fiction is full of paradoxical and labyrinthine spaces

Brian McHale (1992: 157)

et us imagine that we are about to enter an entirely new space. It might be M.C. Eschers

Another World II. It might be Jorge Luis Borges Tion, Uqbar, Orbis or Tertius or Italo

Calvinos Anastasia or Fantasliea. But the feature shared by all these versions of space

is the impossibility of their coexistence with each other in terms of familiar cognitive,

temporal or spatial codes. In all fiction, Borges tells us in The Garden of Forking

Paths (1964 [1956]: 26),

when a man is faced with alternatives, he chooses one at the expense of the others; in the

almost unfathomable Tsui Pen, he choosessimultaneouslyall of them. He thus creates

various futures, various times which start others that will in their turn branch out and bifurcate in other times.1

Let us imagine that we have entered one of these impossible spaces, that we are confronted

with a gardenthe garden of forking pathsand that within this garden we find, as in George

Cantors Chinese box of infinities, Eschers Waterfall. What else?

What is wrong with this picture? We may observe that in the spaces we have just referred

to, individual elements are not confounded with one another. Echoing the labyrinth theme,

Eschers Waterfall (1961), Borges Garden of Forking Paths (1964 [1956]) and Calvinos

Invisible Cities (1978 [1972]) all involve parallel worlds that produce cognitively impossible

1

Richard Burgin (1968) observes that Eschers work shares some of Borges themes.

The International Journal of the Image

Volume 3, 2013, www.ontheimage.com, ISSN 2154-8560

Common Ground, Zanger Anat Yonat, All Rights Reserved, Permissions:

cg-support@commongroundpublishing.com

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

pictures. Unlike the classic Greek labyrinthwhere Theseus escapes from the maze by following

Ariadnes thread from one point in the structure to anotherthe labyrinth of Escher, Borges,

or Calvino has no structure or center. It is a rhizome in which multiplicity connects one point

to another. If the classic labyrinth might be challenged by its own structure, the structure of

the rhizome is that of a non-hierarchical network of all kinds. As described in Deleuze and

Guattaris A Thousand Plateaus, The rhizome is an acentered, nonhierarchical, nonsignifying

system without a General and without an organizing memory or central automation, defined

solely by a circulation of states (1987: 21).

Accelerated by the development of electronic and digital media, the labyrinth and the rhizome

are among the prevailing themes of contemporary culture and have come to dominate postmodernist aesthetics.2 Contemporary cinema has deployed various kinds of labyrinths. It is my

contention, however, that because of its parallel, non-hierarchical structure, the rhizome is

rarely to be found in so-called postmodernist cinema. This itself may sound like a paradox

but, as I hope to show, this principle is the ghost behind the scenes that keeps the films going

on.

Ernest Gombrich (1961) identifies Escher as a contemporary artist whose prints are meditations on image reading.3 I want to elaborate on this observation and trace its implementation

in postmodernist cinema. To do so, I will first characterize Eschers labyrinth and then trace

the ways in which Escherian labyrinths have been recorded in the cinematic medium. As the

objects of my scrutiny, I have chosen two of Eschers works: Reptiles (1943), Relativity (1953),

and two films: Antonionis Blow-Up (1967) and Cronenbergs Videodrome (1982). Following

Christian Metz (1979), I intend while analyzing these texts to trace the paradox of presence/absence as inscribed in the cinematic image. As I will show in this paper, Escher developed at least

two kinds of labyrinths, but only one has so far inscribed itself in postmodernist cinema.4

Eschers Meditations on Image Reading

M.C. Escher introduces Reptiles (1943) first under the category of the regular division of a

plane and secondly as the sub-category of story-pictures.5 Escher describes the story of the

Reptiles as the life-cycle of a little alligator as it climbs up the back of a book on zoology and

works his laborious way up the slippery slope of a set square to the highest point of his existence.

Then [] he goes downhill again, [] taking up once more his function as an element of surface

division (Escher, 1992 (1959: 10).6 Martin Gardner, citing Escher, adds:

The border line between two adjacent shapes is a complicated business. On either side of it,

simultaneously, a recognizability takes shape. But the human eye and mind cannot be busy

with two things at the same moment and so there must be a quick and continuous jumping

from one side to the other. But the difficulty is perhaps the very moving-spring of my perseverance (Gardner: 1990 [1975]: 91)

D. Fokkema (1986) observes that words such as mirror, labyrinth, map, journey (without destination),

[...] television, and photograph [...] are frequently used lexemes in postmodernist texts (ibid: 87). See also Jencks

(1984) on postmodernist space, cited in McHale (1992: 158), see the analogy that McHale draws between Cortazars

Continuity of Parks and Eschers Print Gallery (1987).

3

Doris Schattschneider cites Gombrich (1961) in her Visions of Symmetry-Notebooks, Periodic Drawings and Related

Work of M.C. Escher (1990: 280).

4

See also M. Gardner 1975 [1965]: 93 on different categories in Eschers work.

On cinematic labyrinths see also M. Friedman (1991), The Historical Thriller: The Double Labyrinth [Hebrew] in:

Zemanim-A Historical Quarterly; and T. Kougler, 1994, Labyrinth as a Representative Model of Detective Movies

in Moutar, Tel-Aviv University, Faculty of the Arts, no. 2 pp. 149158.

5

M.C. Escher-The Graphic Work, 1992 (1959).

6

Escher adds the following remark: The title book of Job has nothing to do with the Bible, but contains Belgian cigarette papers (ibid: 10).

ANAT YONAT: PARALLEL IMAGES

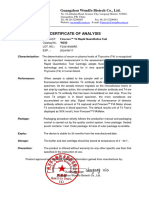

(Reptiles, M.C. Escher, 1943)

What differentiates Print Gallery, Waterfall, High & Low, or Relativity from Reptiles? What

is the quality that places the latter text in a different sub-category?7 Escher places Another

World II, High & Low, as well as Relativity in the category of Relativities:

[...] It is impossible for the inhabitants of different worlds to walk or sit or stand on the

same floor, because they have differing conceptions of what is horizontal and what is

vertical. Yet they may well share the use of the same staircase. On the top staircase [...]

two people are moving side by side and in the same direction, and yet one of them is going

downstairs and the other upstairs. Contact between them is out of the question because

they live in different worlds and therefore can have no knowledge of each others existence

(ibid: 14).

Interestingly, High and Low (1947) is introduced by Escher in a different sub-category, that of Relativities. Print

Gallery (1956) as well as Drawing Hands (1948) are in the category of Conflict flat-spatial while Belvedere (1958),

Ascending and Descending (1960), as well as Waterfall (1961) are presented in the last category: that of Impossible

Buildings (ibid: pp. 716).

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

(Relativity, M.C. Escher, 1953)

While all the Escher works mentioned here revolve around the labyrinth theme, the impossibility

of each is generated by a different kind of paradox. In this respect, Reptiles might be considered

representative of the first group, that of ontological violations. Different ontological levels are

presented to the beholder; some seem to belong to a first degree of reality and others to a

second degree of reality. However, by frustrating transference from one level to another and

back again, the viewers glance fixes on the production mechanism of the text itself. Thus, the

surface of the ontological violation presents tangled hierarchies (Hofstadter: 1980[1979]:

691). Through shifts between different ontological levels of reality or worlds, the global effect

is one of ontological violation, suggesting that no level is truer than any other.

ANAT YONAT: PARALLEL IMAGES

Chart 1: Shifting between Different Ontological Levels of Reality

The labyrinth created by Relativity or Waterfall rests on entirely different principles of possible

world construction, involving, simultaneously, multiple worlds on the same ontological level.

Borges The Garden of Forking Paths presents an impossible story created by the presence

of too many versions playing themselves out on the same ontological level.8 Eschers Relativity,

Print Gallery, or Ascending and Descending work the same way. As Gombrich would have it:

Watching ourselves trying to read the print in terms of a possible world, we gain some insight

into the beholders share in all readings of spatial arrangement (1960 [1959]: 208). After all,

in terms of our knowledge, it is similar to viewing the same picture twice, but simultaneously

from different vantage points.

Violating the familiar either/or relationship, this type of labyrinth suggests the additive relation:

the simultaneous presence of multiple worlds on the same ontological level. The global effect

forces the viewer to meet the ellipse of representation, that lacks the center of meaning

(Foucault, 1986).

Chart 2: Multiple Worlds on the same Ontological Level

McHale (1987) identifies The Garden of Forking Paths as a paradigm for both Ecos Pynchons and Calvinos postmodernist novels. (ibid: 106).

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

Films Impossible Picture

Let me now trace the uses of Eschers labyrinths in film, via a still picture, being taken in a park

by a photographer who is himself being photographed by Antonionis camera in Blow-Up

(1967).9 Blow-Up is a cinematic text that self-reflexively discusses its medium, its limits of

representation, and the way it records-or, rather, simulates-the reality alluded to. In an Escherian

way, the viewer of Blow-Up is haunted by the notion that each level of reality has yet another,

additional level and each fictional level has a still more fictional one.

Thomas (David Hemmings) is a photographer in swinging London of the 1960s. Idly, he

visits a park, meets a woman (Vanessa Redgrave), and photographs her with her male friend.

She demands the film from him but he refuses. Later, he develops the film, enlarges it and begins

to suspect that the man in the park was murdered, that someone was waiting for him in the

bushes.

The main riddle of the narrative revolves around the question: was there a murder in the

park or not? This speculation gives rise to other questions such as: why didnt Thomas inform

the police about the event in the park? Who is the girl? What does she want? Since the film

does not supply definite answers to these questions, the spectator has to look for different

questions to be asked. Was there a murder in the park? Was there a body in the park? The

spectators see the body in the enlargement made by Thomas. He sees the body lit by a neon

light on grassbut the next morning there is no sign of it. So was there a body or was it only

an optical illusion? And, consequently, what meaning can we attribute to the fact that towards

the end of Antonionis film, Thomas himself gradually dissolves.

The spectators of Blow-Up are never given the keys required for cognitive mapping (to

use Jamesons term, 1984). Much like the viewers of Eschers Reptiles (1943) or Dewdrop

(1948), who seem to have lost their way between representations of second-degree reality

and first-degree reality merely in order to ultimately discover that both levels lie within the

same artistic text, itself second-degree reality. Thus, in Blow-Up, the pictures are stolen, the

enlargement in which Thomas saw the body remains, but he himself does not recognize the

body in the stained mosaic of the enlargement even though he had seen it before. Patricia, his

friend, does not see the body in the picture, the body itself has vanished from the park without

leaving any evidence that it ever existed.10 And then Thomas himself vanishes from the screen.

The image-reading process undergone by the spectator revolves around attempts to solve the

following ontological tension:

1.

2.

3.

The disappearance of the picture of the body is interpreted by the spectator as: this is only

a picture, hence a second degree of reality within the world of the picture.

The disappearance of the body itself is interpreted by the receiver as part of the reality of

the movie (part of its plot).

The disappearance of Thomas signifies: this is only a movie!!

Rephrasing Hofstadter in: Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (1980 [1979]), we

may describe the process as follows: focusing on the blow-up, we get the message that sign and

body are two different things. Then our gaze moves towards the real body, the one that we

perceive to be real. At this point, it seems that this body is real, while the enlarged picture is

only a signifier. But both readings are wrong; since both are only points of electronic color superimposed on the same flat surface.

9

In contrast to a theoretician like iek (1991) who identifies Antonionis film as [...] the last great modernist film

(ibid: 143), I consider Antonionis film as recording an aesthetic shift of norms between modernism and postmodernism.

As such, it involves both epistemological and ontological questions, but the latter are foregrounded. See also Zanger,

1993.

10

See also Antonionis script p. 112.

ANAT YONAT: PARALLEL IMAGES

The idea that one level of the picture is less real than the other is false. In an Escherian

manner, once we are willing to enter the Print Gallery or, as it were, the movie theater, we

have already been tricked: we have perceived the film as reality.11 And rephrasing Hofstadter

again, (1980 [1979]: 701), the only way not to be sucked in is to see both bodies as colored

smudges on film, to identify both as spots of light and colors on celluloid. Then and only then,

do we appreciate the full meaning of Patricias declaration: It looks like one of Bills [abstract]

paintings signifying this is not a body. Thomas himself becomes no more than an electronic

vibration, a recorded signal as does Patricias declaration: This is not a body. In other words,

at the very moment that the film points to its production, its own simulacra, the message of

the film is destroyed.12

The Photographer in Blow Up, Michelangelo Antonioni (1967), Photographed by Arthur Evans, BFI/MGMWB

Videodrome, directed by David Cronenberg (1982), seems to be the virtual-reality version of

Blow-Up. Like Blow-Up, Videodrome produces a recursive self-referentiality that absorbs the

viewer into its strange loop. Similar to Eschers Reptiles or Dewdrop, the ontological borders

between the different levels of reality are blurred: the TV screen in Videodrome is contained

by its own frame, but Cronenbergs close-ups permit the image to burst out of its boundaries

and expand beyond the inner world of the film to the full proportions of the cinema screen.

Later on, when Max Renn puts a videotape into his machine, Cronenberg inserts a blip of video

distortion over the entire visual field. According to Bukatman (1993), this insert does not signify

hallucination but rather infects the viewer with a similar experience of decayed boundaries.

11

12

Or in a Godelian way, as Douglas Hofstadter would have it (1980 [1979]).

Echoing Magrittes Ceci nest pas une pipe in his The Two Mysteries. See also Zanger, 1993.

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

No cinematic register differentiates hallucination from reality or second-degree reality for

the viewer. The absence of such a register throws discourse itself into question.13 However, the

film does not present the multiple worlds existing on one ontological level. The reading process

of Videodrome might involve possible worlds, but the viewer does not discover that there is

not one world but a plurality of competing worlds or better; if there is one world, it includes

a multiplicity of conflicting perspectives (Merrell, 1991: 4). During the screening of a few

segments, like that of the video distortion, the viewer might believe that Videodrome is more

than reality (as Brian OBlivion, one of the films characters says), but the global effect is that

of alternating between different degrees of reality.

The Ghost Behind the Scene

V. Perkins (1972) has made the observation that while a painting creates a world, still-photographs and, subsequently, cinema create the world.14 The cinematic medium, by its very nature,

takes the issue of representation to its extreme. But if postmodernist labyrinth-makers like

Escher, Borges, or Calvino show that each particular perspective of the world is only a world

and not the world, the Gordian knot connecting the cinematic medium and its representation

of reality make this not too easy a task. Interestingly, the first kind of labyrinth, i.e. alternation

between different levels of reality, became one of the hallmarks of postmodern cinema. In

addition to Videodrome, other familiar examples are Brazil by Terry Gilliam (1982), True

Stories by David Byrne (1982), The Purple Rose of Cairo by Woody Allen (1985) and Pleasantville by Gary Ross (1998), to mention just a few. In these films, different levels of realities

threaten the familiar order, but the dnouement supplies a realistic motive that retrospectively

rearranges the various levels in the familiar order. The second type of labyrinth, however,

evoked by the simultaneous presence of multiple worlds belonging to the same ontological level

is rarely found in postmodernist cinema. Partial experiences come from the domain of video

art, independent cinema, and the genre of science fiction. Examples, apart from Videodrome,

might include La Jete by Chris Marker (France, 1969), Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky (USSR,

1972), Buena Vista by Thierry Kuntzell (France, 1980), and Speaking Parts by Atom Egoyan

(Canada, 1989) that succeed in creating a nonhierarchical network rather than a coherent

world. Despite their concrete material of sounds and images, parallel worlds are introduced

before the spectators eyes in such a way that the global effect created by the films sustains the

impossible coexistence of entities competing for the same ontological level.15

In his study on Postmodernism, Brian McHale (1987) suggests a paradigmatic model that is

characterized by a change of the dominant in a given worldview.16 According to McHale, the

epistemological dominant engages and foregrounds such questions as: What is there to be

known? Who knows it? How do they know it, and with what degree of certainty? (1987:7).

The ontological dominant engages and foregrounds such questions as: What is a world? What

kinds of worlds are there, how are they constituted, and how do they differ? (ibid: 9). However,

the affinity between these two dominants leads to an exchange between foreground and back-

13

See Bukatmans analysis.

Interestingly, McHale (1987) observes that: an ontology is a description of a universe, not of the universe; that is,

it may describe any universe, potentially a plurality of universes (McHale, 1987: 27; emphases are in the text).

15

Yet, in view of the new technologies emerging in both electronic and digital media, it is quite possible that more

multiple worlds will be produced in the futurethrough Virtual Reality technologies, interactive cinema, or entirely

new procedures.

16

The dominant should be understood in the context of Russian Formalism as the focusing component in the work

of art through which the hierarchical structure of devices is achieved (Jakobson 1971 [1935]); in McHale, 1987: 6.

14

ANAT YONAT: PARALLEL IMAGES

ground: thus epistemology is foregrounded in modernist texts, while ontology is backgrounded,

and the reverse is true for postmodernist ones (ibid: 11).17

Replacing the question of How do aesthetics and culture norms function in principle? by

How do aesthetic and cultural norms function along the time axis? will allow us to identify

Blow-Up (1966) and not only Videodrome (1982) as postmodern. Engaging both epistemological and ontological questions, Blow-Up shifts epistemological questions to the background

during the reading process and demands the foregrounding of a set of new questions, i.e., ontological ones.18 However, popular postmodernist cinema may adopt non-linear narratives or

large quantities of intertextuality, but not a multiplicity of ontological levels. Such a multiplicity

would create a rupture between the film and its represented world. Thus, Kenneth Branaghs

Dead Again (1991) or Quentin Tarantinos Pulp Fiction (1993) merge present and past and

male and female identities, but their rhetorical devices maintain the retrospective unity of both

space and time with regard to narrative events. As Christian Metz has already observed (1979),

one of the main oppositions in cinema is between absence and presence. The film asks its

viewers to believe that the world presented to them, a world of light and shadow, is real.

Thus, it has to be very careful about the way in which it employs possible worlds in order to

build and rebuild its imagined world.19 Maybe this is the reason why even postmodernist cinema

cannot allow itself to make wide use of a rhizome.

17

McHales model recognizes the transformation of sensibilities, whose treatment is based on the shift of the dominantthus leaving space for each of the little narratives of postmodernist texts to inscribe themselves in culture.

Little narratives have come to replace the idea of le grand rcit in the traditions of modernist Western culture.

18

This structure is made available through three different writings that work independently and are recorded on the

film: the camera gesture, the actors gesture and the sound gesture; each gesture consistently cast doubt on the other

gestures.

19

Peter Wollens 1982.

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE IMAGE

REFERENCES

Antonioni, Michelangelo, 1967, Blow-Up (Great Britain, Ponti & MGM) Based on Julio

Cortazars story: The Devils Drools.

Borges, Jorge-Luis, 1964, Labyrinths-Selected Stories & Other Writings Ed. by Donald A. Yates

& James E. Irby. A Preface by Andre Maurois. A New Directions Book, 1964.

Bukatman, Scott, 1993, Terminal Identity-The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction.

Duke University Press, Durham and London 1993.

Burgin, Richard, 1968, Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges New York: Holt, Rinehart &

Winston.

Calvino, Italo, 1978 (1972) Invisible Cities, translated by William Weaver Helen & Kurt Wolff

Books, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Cronenberg, David, 1982, Videodrome, Canadian Film Development Corporation & Famous

Players Ltd.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix, 1987, A Thousand Plateaus-Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

Translated and foreword by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis & London: University of

Minnesota Press.

Derrida, Jacques, 1981(1966) Ellipsis in Writing and Difference, trans. by Alan Bass pp.

294300. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Escher, M.C. 1992 (1959), M.C. Escher-The Graphic Work Introduced and Explained by the

Artist. Koln: Benedikt Taschen.

Fokemma, Douwe, 1987 The Semantic and Symbolic Organization of Postmodernist Texts

In: Approaching Postmodernism: Papers Presented at a Workshop on Postmodernism,

ed. Douwe Fokkema pp. 8199 Utrecht: University of Utrecht.

Foucault, Michel, 1986, Of Other Space, in Diacritics 16 (1).

Friedman, R. Mihal, 1991, The Historical Thriller: The Double Labyrinth [Hebrew] in: Zemanim-A Historical Quarterly published by the Aranne School of History, Tel Aviv

University & Zmora-Bitan. vol. 3940, Winter, 1991.

Gardner, Martin, 1976, The Art of M.C. Escher in: Mathematical Carnival London: Penguin

Books pp. 89102.

Hofstadter, Douglas, 1979, Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid New York: Vintage

Books, A Division of Random House, 1980.

Jakobson, Roman, 1971, The Dominant in: Reading in Russian Poetics: Formalist and

Structuralist Views, edited by Matejka Ladislav and Kristine Pomorska. Cambridge,

MA and London: MIT Press.

Jameson, Fredric, 1984, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism in: New

Left Review 146, 5392.

Jencks, Charles, 1984, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, Fourth revised edition,

London: Academy Edition.

_______, 1986 [1982] What is Post-Modernism? London: Art & Design.

McHale, Brian, 1987, Postmodernist Fiction, New York: Methuen.

_______, 1992, Constructing Postmodernism, London and New-York: Routledge.

Megill, Allan, 1985, Prophets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Derrida London,

Berkeley and Los-Angeles: University of California Press.

Merell, Floyd, 1991, Unthinking Thinking-Jose Luis Borges, Mathematics, and the New

Physics. West Lafayette Indiana: Purdue University Press.

Schattschneider, Doris, 1990, Visions of Symmetry: Notebooks, Periodic Drawings, and Related

Work of M. C. Escher. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Stallabrass, Julian, 1996, Empowering Technology in: Gargantua-Manufactured Mass Culture

pp. 4083. London & New York: Verso, 1996.

10

ANAT YONAT: PARALLEL IMAGES

Zanger, Anat, 1993, Blow-Up-Between Modernism and Post-Modernism in: Meoznaim vol.

42 Sep-Oct. [Hebrew]

iek, Slavoj, 1991, Looking Awry-An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture.

Cambridge, MA & London, UK: October Books, MIT Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zanger Anat Yonat: Anat Y. Zanger is an associate professor in the Department of Film and

Television and chair of the MA in Film Studies at Tel Aviv University. Her research interests

include: Israeli cinema, mythology, collective memory, intertextuality, and space and landscape.

She is the author of Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguises (Amsterdam University Press, 2006)

and Place, Memory and Myth in Contemporary Israeli Cinema (Valentine Mitchell, 2012).

11

The International Journal of the Image interrogates

the nature of the image and functions of imagemaking. This cross-disciplinary journal brings together

researchers, theoreticians, practitioners and teachers

from areas of interest including: architecture, art,

cognitive science, communications, computer science,

cultural studies, design, education, film studies, history,

linguistics, management, marketing, media studies,

museum studies, philosophy, photography, psychology,

religious studies, semiotics, and more.

As well as papers of a traditional scholarly type, this

journal invites presentations of practiceincluding

documentation of image work accompanied by

exegeses analyzing the purposes, processes and

effects of the image-making practice.

The International Journal of the Image is a peerreviewed scholarly journal.

ISSN 2154-8560

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Quantitative Research in Education A PrimerDocumento160 pagineQuantitative Research in Education A PrimerHugoBenitezd100% (4)

- ListDocumento18 pagineListJer RamaNessuna valutazione finora

- EE1071 Introduction To EEE Laboratories - OBTLDocumento7 pagineEE1071 Introduction To EEE Laboratories - OBTLAaron TanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Financial Stability On Student Academic PerformanceDocumento2 pagineThe Impact of Financial Stability On Student Academic PerformanceYvonne AdrianoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Event and The Responsibility of The Image - Just Images: Ethics and The Cinematic, Boaz Hagin, Sandra Meiri, Raz Yosef and Anat Zanger (Eds.), Cambridge Scholar Publishers, 2011 - Anat ZangerDocumento13 pagineThe Event and The Responsibility of The Image - Just Images: Ethics and The Cinematic, Boaz Hagin, Sandra Meiri, Raz Yosef and Anat Zanger (Eds.), Cambridge Scholar Publishers, 2011 - Anat ZangerAnat ZangerNessuna valutazione finora

- City and Memory: Jerusalem in Israeli Cinema - Israel Studies, 2016 - Anat ZangerDocumento16 pagineCity and Memory: Jerusalem in Israeli Cinema - Israel Studies, 2016 - Anat ZangerAnat ZangerNessuna valutazione finora

- Between Homeland and Prisoners of War: Remaking Terror - Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 2015 - Anat ZangerDocumento13 pagineBetween Homeland and Prisoners of War: Remaking Terror - Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 2015 - Anat ZangerAnat ZangerNessuna valutazione finora

- Just Look at Yourselves - The Face and The Ethical Event in Israeli Cinema - Studies in Documentary Film, 2012 - Anat ZangerDocumento17 pagineJust Look at Yourselves - The Face and The Ethical Event in Israeli Cinema - Studies in Documentary Film, 2012 - Anat ZangerAnat ZangerNessuna valutazione finora

- SalDocumento8 pagineSalRobertoNessuna valutazione finora

- ResearchDocumento4 pagineResearchClaries Cuenca100% (1)

- Week 9-1 - H0 and H1 (Updated)Documento11 pagineWeek 9-1 - H0 and H1 (Updated)Phan Hung SonNessuna valutazione finora

- An Authors Guideline For Obstetrics and GynDocumento9 pagineAn Authors Guideline For Obstetrics and Gynmec429Nessuna valutazione finora

- Application Prototype Test and Design ReportDocumento6 pagineApplication Prototype Test and Design ReportAndreea-Daniela EneNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus HE20203Documento2 pagineSyllabus HE20203Pua Suan Jin RobinNessuna valutazione finora

- Cigarette Smoking Teens Published JNSRDocumento10 pagineCigarette Smoking Teens Published JNSRJusil RayoNessuna valutazione finora

- Instructional Supervisory Plan Cajidiocan CES 2022Documento8 pagineInstructional Supervisory Plan Cajidiocan CES 2022Mariel Romero100% (1)

- A Very Brief Introduction To Machine Learning With Applications To Communication SystemsDocumento20 pagineA Very Brief Introduction To Machine Learning With Applications To Communication SystemsErmias MesfinNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire - Development of A Short 18-Item Version (CERQ-short)Documento9 pagineCognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire - Development of A Short 18-Item Version (CERQ-short)leonardNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis On Road Accident in GhanaDocumento5 pagineThesis On Road Accident in Ghanaafcnftqep100% (2)

- Costs of Equity and Earnings AttributDocumento45 pagineCosts of Equity and Earnings AttributhidayatulNessuna valutazione finora

- Theoretical Framework & VariablesDocumento8 pagineTheoretical Framework & Variablessateeshmadala8767% (3)

- UM Research ReportDocumento41 pagineUM Research Reportasykuri ibn chamimNessuna valutazione finora

- Designing A Final Drive For A Tracked VehicleDocumento9 pagineDesigning A Final Drive For A Tracked VehicleIroshana Thushara KiriwattuduwaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3Documento5 pagineChapter 3Sheila ShamimiNessuna valutazione finora

- Barkway2001. Michael Crotty and Nursing PhenomenologyDocumento5 pagineBarkway2001. Michael Crotty and Nursing PhenomenologymalextomasNessuna valutazione finora

- T4 Rapid Quantitative Test COA - F23216309ADDocumento1 paginaT4 Rapid Quantitative Test COA - F23216309ADg64bt8rqdwNessuna valutazione finora

- HR001123S0011Documento57 pagineHR001123S0011Ahmed LaajiliNessuna valutazione finora

- Discovery Approach: Creating Memorable LessonsDocumento4 pagineDiscovery Approach: Creating Memorable LessonsAljo Cabos GawNessuna valutazione finora

- Fly Ash From Thermal Conversion of Sludge As A Cement Substitute in Concrete ManufacturingDocumento14 pagineFly Ash From Thermal Conversion of Sludge As A Cement Substitute in Concrete Manufacturingrhex averhyll jhonlei marceloNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Online Learning Mode in Psychological Aspect of College StudentsDocumento4 pagineEffects of Online Learning Mode in Psychological Aspect of College StudentsChrizel DiamanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Organizational Risk Factors A Case Study of Hydroelectric Power Projects, MyanmarDocumento161 pagineKey Organizational Risk Factors A Case Study of Hydroelectric Power Projects, Myanmarhtoochar123100% (3)

- ER Diagrams Examples PDFDocumento494 pagineER Diagrams Examples PDFRDXNessuna valutazione finora

- 1976 - Roll-Hansen - Critical Teleology Immanuel Kant and Claude Bernard On The Limitations of Experimental BiologyDocumento33 pagine1976 - Roll-Hansen - Critical Teleology Immanuel Kant and Claude Bernard On The Limitations of Experimental BiologyOmar RoblesNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhutans Gross National HappinessDocumento4 pagineBhutans Gross National HappinessscrNessuna valutazione finora